Abstract

AIM: To evaluate a levofloxacin-doxycycline-based triple therapy with or without a susceptibility culture test in non-responders to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication.

METHODS: A total of 142 (99 women, 43 men; mean 53.0 ± 12.7 years) non-responders to more than two H. pylori eradication therapies underwent susceptibility culture tests or were treated with a seven-day triple therapy consisting of esomeprazole, 20 mg b.i.d., levofloxacin, 500 mg b.i.d., and doxycycline, 100 mg b.i.d., randomly associated with (n = 71) or without (n = 71) Lactobacillus casei DG. H. pylori status was checked in all patients at enrollment and at least 8 wk after the end of therapy. Compliance and tolerability of regimens were also assessed.

RESULTS: H. pylori eradication was achieved in < 50% of patients [per prototol (PP) = 49%; intention to treat (ITT) = 46%]. Eradication rate was higher in patients administered probiotics than in those without (PP = 55% vs 43%; ITT = 54% vs 40%). Estimated primary resistance to levofloxacin was 18% and multiple resistance was 31%. Therapy was well tolerated, and side effects were generally mild, with only one patient experiencing severe effects.

CONCLUSION: Third-line levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy had a low H. pylori eradication efficacy, though the success and tolerability of this treatment may be enhanced with probiotics.

Keywords: Doxycycline, Eradication therapy, Urea breath test, Esomeprazole, Levofloxacin, Helicobacter pylori

Core tip: Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy should be based on a culture sensitivity test or include antibiotics not already used by patients who failed to respond to two or more previous attempts. Third-line levofloxacin-based triple therapy was demonstrated to be effective in such kind of patients. In the present study, a third-line levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy, associated or not with probiotics, was able to eradicate H. pylori infection in about 50% of patients. The low eradication rate achieved by the study regimen was probably due to levofloxacin resistance. Further studies on larger series are needed to confirm the efficacy of levofloxacin-containing regimens in Italy.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a cause of gastritis and plays an important role in the development of gastric cancer[1]. Standard triple therapy (STT), consisting of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) associated with clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole, is still considered the first-line treatment of H. pylori in Europe, the United States, and Asia[2-4], though a progressive decrease in eradication rates has been observed in the last decade[5-7]. Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, sequential therapy, or non-bismuth quadruple therapy, namely concomitant, have been proposed as alternative first-line regimens in countries where resistance to clarithromycin is > 15%-20%[8]. A levofloxacin-based triple therapy, in which levofloxacin is associated with amoxicillin or tinidazole plus a PPI, may be also used as second-line treatment to cure H. pylori infection after failure of a PPI-clarithromycin-containing therapy, with eradication rates > 90% in patients found to have microorganisms resistant to clarithromycin or metronidazole[9-11]. According to the Maastricht IV consensus on management of H. pylori infection[8], after two treatment failures, antibiotics not previously used should be prescribed or, whenever possible, culture of H. pylori with susceptibility testing may be useful to tailor a possibly more active regimen. However, culture tests are not widely used and have limited acceptance, subordinate to collection of gastric biopsy specimens during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (EGDS), and several technical factors may influence their reliability. For these reasons, as an alternative approach, levofloxacin-based triple therapy has been proposed as third-line therapy[12]. Tetracycline is another antibiotic mainly used in bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, found to be effective in the eradication of H. pylori strains not responding to previous treatments[13,14]. Doxycycline is a tetracycline analogue that may be administered once or twice daily, instead of four times per day, possibly improving compliance and tolerability[15].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate whether administration of an esomeprazole-levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy, with or without supplementation of probiotics, may be effective in patients not responding to at least two attempts of H. pylori eradication with or without a prior susceptibility culture test.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of patients and clinical evaluation

A total of 142 consecutive patients (99 women and 43 men) with a mean age of 53.0 ± 12.7 years (range 18-75 years) who were referred to our institution for management and treatment of resistant H. pylori infection were enrolled in the study. The majority of the patients (136/142; 96%) did not smoke, and 85/142 (60%) had a body mass index (BMI) ≤ 25. All patients were recruited following an urea breath test or during a clinical visit performed for persistence of microorganism following ≥ 2 eradication regimens. Exclusion criteria were: age < 18 or > 75 years, a previous treatment with a levofloxacin-based therapy for eradicating H. pylori infection, gastric surgery, liver and/or renal failure, pregnancy or lactation, intellectual impairment, a known allergy or intolerance to study drugs, and a possible low compliance. Patients with periodontal disease, lingual burning, and halitosis possibly related with H. pylori infection in the mouth[16] were also excluded. Once selected, all patients gave their informed consent. Therapies used for eradicating H. pylori prior to the study entry were: STT for 7 d and 14 d (115/142; 81%) or ten-day sequential therapy (amoxicillin 1 g b.i.d. + PPI for 5 d followed by clarithromycin 500 mg b.i.d. + tinidazole 500 mg b.i.d. + PPI for 5 d) after failing STT for 7 d (27/142; 19%).

Susceptibility culture test, eradication therapy, and assessment of post-therapy H. pylori status

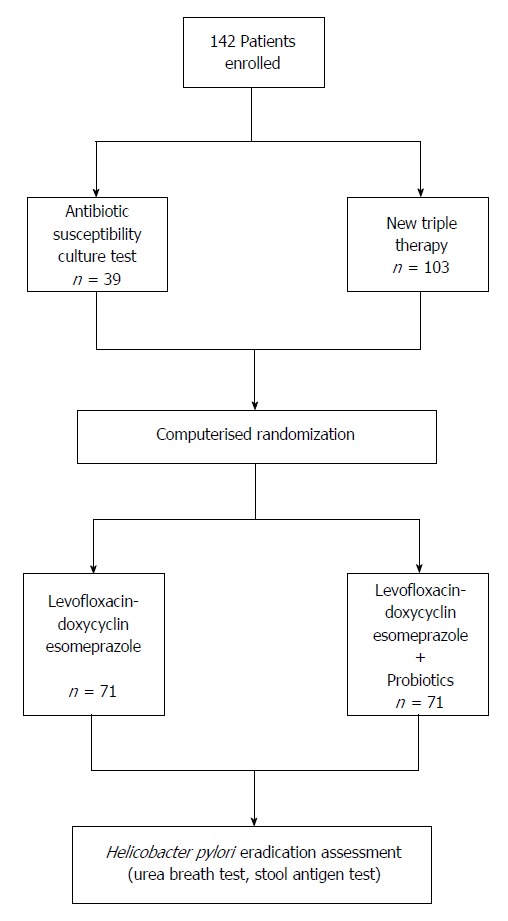

The investigation was an open-label, single-center study. Figure 1 shows the design of the study.

Figure 1.

Design of the study.

At entry, EGDS with an antibiotic susceptibility culture test was recommended to all patients. For those who underwent EGDS, four biopsy specimens were collected from the antrum and body. Tissue specimens were then immediately plunged into an agar-based medium (Portagerm pylori PORT-PYL; bioMerieux, France), specifically produced for storage and transport of gastric biopsies to increase viability of H. pylori, and cultured within 2 h after collection. Antibiotic susceptibility of H. pylori was determined by E-test on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (bioMerieux, France) supplemented with 5% sheep blood. A sterile swab was dipped into a bacterial suspension equivalent to a No. 2 McFarland standard. After swabbing the entire plate surface with inoculum, the following sterile E-test strips were placed on the agar surface: clarithromycin, amoxicillin, metronidazole, tetracycline, and levofloxacin. Plates were incubated at 37 °C under microaerobic conditions and 98% humidity for 3-4 d[17,18]. Interpretation for the susceptibility was according to EUCAST clinical breakpoints (BP) (version 3.1 in 2013 and 4.0 in 2014; both available at the website http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints). The BPs were at minimum inhibitory concentration ≤ 8.0 mg/L, ≤ 0.25 mg/L, ≤ 0.12 mg/L, and ≤ 1 mg/L for metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline and levofloxacin, respectively.

Patients who refused susceptibility culture test were prescribed a levofloxacin-doxycycline based triple therapy for 7 d consisting of levofloxacin 500 mg b.i.d. plus doxycycline 200 mg b.i.d. and esomeprazole 20 mg b.i.d. with (n = 71) or without (n = 71) a 24-billion lyophilized preparation of Lactobacillus casei DG (Sofar, Milan, Italy). Patients were allocated to triple therapy with or without the probiotics according to a computerized randomization in blocks of two. All drugs were dispensed by Italian National Health System, and, therefore, were in marketed packages.

H. pylori eradication was assessed by an urea breath test and by an antigen stool test at least 8 wk after the end of therapy.

Tolerability and compliance

Tolerability of therapy was evaluated by a standard questionnaire[19], which was given, in an anonymous form, at the time of therapy prescription and to be filled during the treatment period. The questionnaire encompassed a series of adverse events, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, taste perversion, headache, rash, and anorexia, and had to be returned at post-therapy control. Patients were also requested to record any other adverse events. Each symptom was scored daily according to the following criteria: absent (score 0) = not appreciable; mild (score 1) = slightly perceived, not interfering with daily activities, therapy assumed as prescribed; moderate (score 2) = well evident, with a slight limitation of daily activities, therapy continued as prescribed; severe (score 3) = very intense, with a marked limitation or impossibility to perform daily activity, and the need to stop drug intake. In the event of severe symptoms, patients were asked to contact our institution, either by telephone or by undergoing a clinical visit, and one of the doctors taking part in the study evaluated whether the adverse event was therapy-related and whether withdrawal of the drugs necessary. Causality was assessed by using the temporal relationship of the symptom to the start of therapy.

Compliance was evaluated by counting the number of pills left in the packages returned at post-therapy control and was defined as good if > 90% of the tablets had been taken.

Statistical analysis

Rates of patients found to be eradicated were calculated according to intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) criteria. Proportions of patients eradicated and not eradicated were compared according to the use of probiotics and other clinical parameters. Statistical analysis was made using Student’s t, χ2, or Fisher’s exact texts when appropriate. A value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Pre-treatment antibiotic susceptibility culture test

Of the 142 patients enrolled in the study, only 39 (27%) accepted to undergo EGDS with culture antibiotic susceptibility test; H. pylori susceptibility to all tested antibiotics was found in 4/39 (10%) patients, resistance to clarithromycin was found in 12/39 (31%), metronidazole in 25/39 (64%), and levofloxacin in 7/39 (18%) patients. Mixed antibiotic resistance was found in 12/39 (31%) patients. Susceptibility test failed to give reliable results in seven cultures for contamination (n = 4) or absence of bacterial growth (n = 3).

Eradication of H. pylori infection

All 142 patients received the levofloxacin-doxycycline based triple therapy, 71 of them in association with probiotics and 71 without. At the end of the study, 4 patients were lost to follow-up as they did not present at post-therapy clinical control, and 4 dropped out due to protocol violation (n = 1), low compliance (n = 2), and withdrawal from the therapy due to a severe side-effect (n = 1). Of the remaining 134 patients in whom eradication of H. pylori was assessed, 66 were found to be H. pylori-negative and 68 H. pylori-positive. Thus, overall eradication rate was 46% according to ITT and 49% according to PP criteria. The eradication rate in patients taking probiotics was greater, but not significantly, than in those not taking probiotics in addition to the levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy (PP: 55% vs 43%, P = 0.22, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.818-3.206; ITT: 54% vs 40%, P = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.908-3.444).

No significant difference in the eradication rates was found comparing patients according to BMI value (50% in those with BMI ≤ 25 vs 36% in those with BMI > 25).

Tolerability and compliance

Levofloxacin-based triple therapy was well tolerated in majority of patients. Only one patient (0.7%), taking levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy without probiotics experienced a severe side effect consisting of severe diarrhea requiring withdrawal from the therapy. An additional 11/142 (7.7%) patients, including eight without and three with probiotics, reported the occurrence of mild symptoms, not interfering with usual daily activity, consisting of bloating, taste perversion, and mild diarrhea.

Compliance was good in all but two patients, who reduced the intake of antibiotics (one patient) or duration of therapy (one patient, six instead seven days).

DISCUSSION

Eradication of H. pylori infection still remains a clinical challenge. To this goal, several therapies have been proposed, but about 30%, and possibly more, of patients remain infected following first- and a second-line eradication attempts[20-23]. The main reason for these failures is the increasing resistance to antibiotics, such as clarithromycin. For this reason, in the Maastricht IV consensus[8], it has been stated that clarithromycin-based STT should be abandoned in countries where resistance to this antibiotic is > 15-20%, and a third-line therapy should be tailored according to a culture test to define antibiotic susceptibility of H. pylori. Such a policy has been successfully validated, as culture test-based eradication therapy cures H. pylori infection in at least 90% of those who did not respond to previous attempts[24]. However, culture tests are not widely available, and their reliability is influenced by variable bacterial density in the stomach, coexistence of different strains in the same patient, lack of growth due to death of H. pylori outside the stomach, and contamination of culture media by other microorganisms[25,26]. Culture tests can be now replaced by rapid molecular techniques, based on PCR assays, but they still are mainly endoscopy-based and their noninvasive use, for example on stools, is not widely accepted[27]. On the other hand, knowing the susceptibility of H. pylori does not guarantee efficacy, as not all patients respond to antibiotics found to be effective against the bacteria in vitro[28,29]. Thus, physicians and patients, taking in mind these possible limitations, sometimes are reluctant to utilize susceptibility culture testing, which requires EGDS and represents an adjunctive cost. Such a situation frequently occurs in the clinical practice and is well represented in our study in which, when pro- and cons were described, only a minority (27%) of patients agreed to undergo an EGDS for a susceptibility culture test and preferred to receive a new eradication therapy including antibiotics not already used. This is a possible approach alternative to culture test in first- and second-line therapy non-responders, according to Maastricht IV statements[8].

The present study shows a low efficacy of a levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy as third-line treatment in patients infected by H. pylori after failure of ≥ 2 previous regimens, with an overall H. pylori eradication rate of < 50%. This finding is in agreement with another multicenter study in Japan that reported a low eradication rate of 43% following a third-line levofloxacin-amoxicillin triple therapy[30]. These figures are far from those reported by previous investigations in which ≥ 80% of patients achieved H. pylori eradication with a levofloxacin-based triple therapy for 7 d or 10 d administered as second-[12,31] or third-line[32-35] therapy. In contrast to previous investigations, we used doxycycline in association with levofloxacin. The efficacy of doxycycline with levofloxacin or other antibiotics has been demonstrated in the eradication of H. pylori as first-line therapy in naive patients[36-38], and in second- or third-line bismuth-containing quadruple therapy[39,40].

A possible explanation for the low eradication rate could be H. pylori resistance to levofloxacin. Levofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone antibacterial agent with a broad spectrum of activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and, due to these properties, is largely prescribed for infections of respiratory system and the genitourinary tract. Thus, H. pylori resistance to levofloxacin depends on the use of this antibiotic in the clinical practice. The probability of H. pylori resistance to levofloxacin increases in persons > 45 years of age[41] and with a history of any quinolone intake in the ten years prior to an eradication attempt with a levofloxacin-based therapy[42]. Prevalence of levofloxacin-resistant H. pylori strains is growing, with a steady annual increase during the last years[41], ranging from 18% up to > 30% in Europe and Asia[43-45]. Eradication rates of 57% have recently been reported in South Korea[46], where a high resistance to levofloxacin has been estimated[47]. Resistance to levofloxacin in our assessment was 18%, a figure in keeping with other estimations of levofloxacin-resistant H. pylori strains in Italy, ranging from 14%[12] to 20%-22%[48,49]. However, we cannot reach a definite conclusion about levofloxacin or doxycycline resistance of H. pylori strains in the present series, as only about one-third of our patients underwent susceptibility culture tests before treatment. This is the main flaw of the current investigation. To note, our levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy was able to eradicate H. pylori infection in seven patients infected by H. pylori that was not sensitive to levofloxacin at the baseline culture susceptibility test. In these seven patients, it is possible that doxycycline was able to overcome levofloxacin resistance and induce H. pylori eradication.

Efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapy has been related with the degree of inhibition of gastric acid secretion, which may vary according to the polymorphism of cytochrome P450 type CYP2C19, with lower rates in subjects with the status of extensive metabolizer[50]. The efficacies of esomeprazole, used in the present study, and rabeprazole for blocking acid secretion are not changed by the metabolizer status related with cytochrome CYP2C19[51].

Probiotics supplementation during a levofloxacin-based triple therapy has been associated with eradication rates higher than that achieved with a same therapy in the absence of probiotics[52]. Recent meta-analyses confirmed that addition of probiotics to eradication therapy increases the probability to cure H. pylori infection and reduces the occurrence of side effects following antibiotic intake[53,54]. Probiotics may favor eradication of H. pylori through the release of inhibitory substances, competition for adhesion or nutrients, host immune modulation, or inhibition of toxins[55]. Our study indicates a beneficial effect of probiotics, as a supplementation of Lactobacillus casei DG improved H. pylori eradication by about 10%, though the effect was not significant likely because of the small sample size. In addition, we observed a slightly lower occurrence of side effects under probiotics. These findings justify the addition of probiotics during an antibiotic combination therapy for eradicating H. pylori.

The findings from the present study should be considered with caution as the prevalence of levofloxacin-resistant H. pylori strains in our population was not known. Therefore, it is not possible to define whether efficacy of levofloxacin-based treatments for H. pylori will rapidly decrease in the next few years in Italy, similar to what happened with clarithromycin. However, prevalence of levofloxacin-resistant H. pylori strains currently estimated in Italy is within the range defined in the Maastricht consensus as a cutoff for abandoning clarithromycin use in the eradication of H. pylori. On the other hand, the present paper is one of the first reports warning that a levofloxacin-based triple therapy may have low efficacy as a third-line regimen in Italy, especially if not based on an antibiotic susceptibility test. It is possible that a levofloxacin-and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy[56] is more effective as a second- and also third-line H. pylori eradication therapy. Further studies on larger series are needed to confirm the efficacy of levofloxacin-containing regimens in Italy. The future availability of methods not requiring endoscopy[57,58] could overcome the reluctance of patients to undergo an endoscopy-based antibiotic susceptibility test, and increase the possibility to tailor a more active therapy for eradication of H. pylori infection.

In conclusion, the levofloxacin-doxycycline triple therapy tested in the present study showed a low efficacy as a third-line therapy for eradication of H. pylori infection, possibly due to an increased resistance to levofloxacin. An antibiotic susceptibility test is therefore recommended to tailor a third-line therapy in order to overcome a possible antibiotic resistance. Probiotics may increase the probability of success and tolerability of H. pylori eradication therapy.

COMMENTS

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection causes peptic ulcers, gastritis, and related conditions favoring gastric cancer. Eradication of H. pylori may prevent recurrence of peptic ulcers and stop the progression of gastritis. However, cure of H. pylori infection may be a clinical challenge in a proportion of patients not responding to first- and second-line treatments. Low efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapies is mainly due to resistance of the bacterium to antibiotics, above all clarithromycin and metronidazole.

Research frontiers

Recent guidelines (Maastricht IV consensus) suggest prescribing a third-line treatment including antibiotics not previously used or following an antibiotic susceptibility culture test in patients not responding to first- and second-line therapies. Previous studies demonstrated the efficacy of third-line levofloxacin-containing regimens for eradication of H. pylori resistant to at least two attempts. However, resistance to levofloxacin is increasing worldwide, possibly reducing the efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapies based on this antibiotic.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In contrast to previous investigations, the present study reports low eradication rates achieved by a triple therapy containing levofloxacin plus doxycycline and esomeprazole, with or without addition of probiotics, in a population of patients not responding to at least two previous treatments in Italy, a country where resistance to levofloxacin is increasing.

Applications

Further studies on large patient series are necessary to confirm the efficacy of levofloxacin-containing regimens for the eradication of H. pylori in Italy. In clinical practice, susceptibility testing prior to eradication therapy could be useful to assess antibiotic sensitivity of H. pylori and tailor a more effective treatment.

Terminology

Urea breath test is a noninvasive diagnostic procedure for detecting H. pylori infection based on the ability of the bacteria to convert, in the stomach, 13C-marked urea to ammonia and 13C-marked carbon dioxide, which is detected in the exhaled breath. Antibiotic susceptibility culture tests consist of placing antibiotics onto plates upon which bacteria are growing from gastric biopsy specimens and observing the growth-inhibitory effect.

Peer-review

The article reports important and valuable data regarding a crucial problem of treatment of H. pylori infection in patients who failed previous treatments. The study shows a low efficacy of a levofloxacin-doxycycline therapy as a third-line treatment, which appeared as an attractive alternative for patients who did not respond to previous eradication attempts. It is worth pointing out that constant monitoring of resistance rates of H. pylori strains is crucial for individualizing treatment regimens and to choose the best one.

Footnotes

Informed consent: All study participants or their legal guardian provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Data sharing: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: December 18, 2014

First decision: January 8, 2015

Article in press: February 13, 2015

P- Reviewer: Adler I, Baik GH, Biernat MM, Shmuely H, Sugimoto M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Matysiak-Budnik T, Mégraud F. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, Lam SK, Xiao SD, Tan HJ, Wu CY, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laheij RJ, Rossum LG, Jansen JB, Straatman H, Verbeek AL. Evaluation of treatment regimens to cure Helicobacter pylori infection--a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:857–864. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurent J, Mégraud F, Fléjou JF, Caekaert A, Barthélemy P. A randomized comparison of four omeprazole-based triple therapy regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1787–1793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iacopini F, Crispino P, Paoluzi OA, Consolazio A, Pica R, Rivera M, Palladini D, Nardi F, Paoluzi P. One-week once-daily triple therapy with esomeprazole, levofloxacin and azithromycin compared to a standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe Y, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, Maekawa S, Kuroda K, Miki I, Kachi M, Fukuda M, Wambura C, Tamura T, et al. Levofloxacin based triple therapy as a second-line treatment after failure of helicobacter pylori eradication with standard triple therapy. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:711–715. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nista EC, Candelli M, Cremonini F, Cazzato IA, Di Caro S, Gabrielli M, Santarelli L, Zocco MA, Ojetti V, Carloni E, et al. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy vs. quadruple therapy in second-line Helicobacter pylori treatment: a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:627–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisbert JP, Bermejo F, Castro-Fernández M, Pérez-Aisa A, Fernández-Bermejo M, Tomas A, Barrio J, Bory F, Almela P, Sánchez-Pobre P, et al. Second-line rescue therapy with levofloxacin after H. pylori treatment failure: a Spanish multicenter study of 300 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:71–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatta L, Zullo A, Perna F, Ricci C, De Francesco V, Tampieri A, Bernabucci V, Cavina M, Hassan C, Ierardi E, et al. A 10-day levofloxacin-based triple therapy in patients who have failed two eradication courses. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delchier JC, Malfertheiner P, Thieroff-Ekerdt R. Use of a combination formulation of bismuth, metronidazole and tetracycline with omeprazole as a rescue therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:171–177. doi: 10.1111/apt.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Gao W, Cheng H, Zhang X, Hu F. Tetracycline- and furazolidone-containing quadruple regimen as rescue treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection: a single center retrospective study. Helicobacter. 2014;19:382–386. doi: 10.1111/hel.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smilack JD. The tetracyclines. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:727–729. doi: 10.4065/74.7.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouziane A, Ahid S, Abouqal R, Ennibi O. Effect of periodontal therapy on prevention of gastric Helicobacter pylori recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:1166–1173. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fontana C, Favaro M, Minelli S, Criscuolo AA, Pietroiusti A, Galante A, Favalli C. New site of modification of 23S rRNA associated with clarithromycin resistance of Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3765–3769. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3765-3769.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glupczynski Y, Broutet N, Cantagrel A, Andersen LP, Alarcon T, López-Brea M, Mégraud F. Comparison of the E test and agar dilution method for antimicrobial suceptibility testing of Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;21:549–552. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paoluzi OA, Visconti E, Andrei F, Tosti C, Lionetti R, Grasso E, Ranaldi R, Stroppa I, Pallone F. Ten and eight-day sequential therapy in comparison to standard triple therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized controlled study on efficacy and tolerability. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:261–266. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181acebef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuhisa T, Kawai T, Masaoka T, Suzuki H, Ito M, Kawamura Y, Tokunaga K, Suzuki M, Mine T, Takahashi S, et al. Efficacy of metronidazole as second-line drug for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in the Japanese population: a multicenter study in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Helicobacter. 2006;11:152–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adamek RJ, Suerbaum S, Pfaffenbach B, Opferkuch W. Primary and acquired Helicobacter pylori resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and amoxicillin--influence on treatment outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:386–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hojo M, Miwa H, Nagahara A, Sato N. Pooled analysis on the efficacy of the second-line treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:690–700. doi: 10.1080/003655201300191941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rispo A, Capone P, Castiglione F, Pasquale L, Rea M, Caporaso N. Fluoroquinolone-based protocols for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8947–8956. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiorini G, Vakil N, Zullo A, Saracino IM, Castelli V, Ricci C, Zaccaro C, Gatta L, Vaira D. Culture-based selection therapy for patients who did not respond to previous treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:507–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopes AI, Vale FF, Oleastro M. Helicobacter pylori infection - recent developments in diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9299–9313. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor NS, Fox JG, Akopyants NS, Berg DE, Thompson N, Shames B, Yan L, Fontham E, Janney F, Hunter FM. Long-term colonization with single and multiple strains of Helicobacter pylori assessed by DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:918–923. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.918-923.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papastergiou V, Georgopoulos SD, Karatapanis S. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: meeting the challenge of antimicrobial resistance. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9898–9911. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.9898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomollón F, Sicilia B, Ducóns JA, Sierra E, Revillo MJ, Ferrero M. Third line treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a prospective, culture-guided study in peptic ulcer patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1335–1338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almeida N, Romãozinho JM, Donato MM, Luxo C, Cardoso O, Cipriano MA, Marinho C, Sofia C. Triple therapy with high-dose proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and doxycycline is useless for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a proof-of-concept study. Helicobacter. 2014;19:90–97. doi: 10.1111/hel.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami K, Furuta T, Ando T, Nakajima T, Inui Y, Oshima T, Tomita T, Mabe K, Sasaki M, Suganuma T, et al. Multi-center randomized controlled study to establish the standard third-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1128–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng HC, Chang WL, Chen WY, Yang HB, Wu JJ, Sheu BS. Levofloxacin-containing triple therapy to eradicate the persistent H. pylori after a failed conventional triple therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zullo A, Hassan C, De Francesco V, Lorenzetti R, Marignani M, Angeletti S, Ierardi E, Morini S. A third-line levofloxacin-based rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bilardi C, Dulbecco P, Zentilin P, Reglioni S, Iiritano E, Parodi A, Accornero L, Savarino E, Mansi C, Mamone M, et al. A 10-day levofloxacin-based therapy in patients with resistant Helicobacter pylori infection: a controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goh KL, Manikam J, Qua CS. High-dose rabeprazole-amoxicillin dual therapy and rabeprazole triple therapy with amoxicillin and levofloxacin for 2 weeks as first and second line rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori treatment failures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1097–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gisbert JP. Letter: third-line rescue therapy with levofloxacin after failure of two treatments to eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1484–1485; author reply 1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu PP, Rayapudi K, Pacana T, Shah NJ, Krishnaswamy N, Flynn M. A randomized study comparing levofloxacin, omeprazole, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline versus triple therapy for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1970–1975. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taghavi SA, Jafari A, Eshraghian A. Efficacy of a new therapeutic regimen versus two routinely prescribed treatments for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, double-blind study of doxycycline, co-amoxiclav, and omeprazole in Iranian patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:599–603. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akyildiz M, Akay S, Musoglu A, Tuncyurek M, Aydin A. The efficacy of ranitidine bismuth citrate, amoxicillin and doxycycline or tetracycline regimens as a first line treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cammarota G, Martino A, Pirozzi G, Cianci R, Branca G, Nista EC, Cazzato A, Cannizzaro O, Miele L, Grieco A, et al. High efficacy of 1-week doxycycline- and amoxicillin-based quadruple regimen in a culture-guided, third-line treatment approach for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:789–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z, Wu S. Doxycycline-based quadruple regimen versus routine quadruple regimen for rescue eradication of Helicobacter pylori: an open-label control study in Chinese patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53:273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor A, Taneike I, Nami A, Fitzgerald N, Ryan B, Breslin N, O’Connor H, McNamara D, Murphy P, O’Morain C. Helicobacter pylori resistance rates for levofloxacin, tetracycline and rifabutin among Irish isolates at a reference centre. Ir J Med Sci. 2013;182:693–695. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-0957-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carothers JJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Bensler M, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Hurlburt DA, Parkinson AJ, Coleman JM, McMahon BJ. The relationship between previous fluoroquinolone use and levofloxacin resistance in Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e5–e8. doi: 10.1086/510074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyanova L, Davidkov L, Gergova G, Kandilarov N, Evstatiev I, Panteleeva E, Mitov I. Helicobacter pylori susceptibility to fosfomycin, rifampin, and 5 usual antibiotics for H. pylori eradication. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79:358–361. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almeida N, Romãozinho JM, Donato MM, Luxo C, Cardoso O, Cipriano MA, Marinho C, Fernandes A, Calhau C, Sofia C. Helicobacter pylori antimicrobial resistance rates in the central region of Portugal. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:1127–1133. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shokrzadeh L, Alebouyeh M, Mirzaei T, Farzi N, Zali MR. Prevalence of multiple drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori strains among patients with different gastric disorders in Iran. Microb Drug Resist. 2015;21:105–110. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jeong MH, Chung JW, Lee SJ, Ha M, Jeong SH, Na S, Na BS, Park SK, Kim YJ, Kwon KA, et al. [Comparison of rifabutin- and levofloxacin-based third-line rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:401–406. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2012.59.6.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang TJ, Kim N, Kim HB, Lee BH, Nam RH, Park JH, Lee MK, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC, et al. Change in antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains and the effect of A2143G point mutation of 23S rRNA on the eradication of H. pylori in a single center of Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:536–543. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d04592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zullo A, Perna F, Hassan C, Ricci C, Saracino I, Morini S, Vaira D. Primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated in northern and central Italy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1429–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saracino IM, Zullo A, Holton J, Castelli V, Fiorini G, Zaccaro C, Ridola L, Ricci C, Gatta L, Vaira D. High prevalence of primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolates in Italy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:363–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Shirai N, Kodaira C, Nishino M, Ikuma M, Ishizaki T, Hishida A. Evidence that the degree and duration of acid suppression are related to Helicobacter pylori eradication by triple therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang HL, Li Y, Hu YF, Xie HG, Zhai SD. Effects of CYP2C19 loss-of-function variants on the eradication of H. pylori infection in patients treated with proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy regimens: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ojetti V, Bruno G, Ainora ME, Gigante G, Rizzo G, Roccarina D, Gasbarrini A. Impact of Lactobacillus reuteri Supplementation on Anti-Helicobacter pylori Levofloxacin-Based Second-Line Therapy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:740381. doi: 10.1155/2012/740381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng X, Lyu L, Mei Z. Lactobacillus-containing probiotic supplementation increases Helicobacter pylori eradication rate: evidence from a meta-analysis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:445–453. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082013000800002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li S, Huang XL, Sui JZ, Chen SY, Xie YT, Deng Y, Wang J, Xie L, Li TJ, He Y, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jonkers D, Stockbrügger R. Review article: Probiotics in gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26 Suppl 2:133–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsu PI, Chen WC, Tsay FW, Shih CA, Kao SS, Wang HM, Yu HC, Lai KH, Tseng HH, Peng NJ, et al. Ten-day Quadruple therapy comprising proton-pump inhibitor, bismuth, tetracycline, and levofloxacin achieves a high eradication rate for Helicobacter pylori infection after failure of sequential therapy. Helicobacter. 2014;19:74–79. doi: 10.1111/hel.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vécsei A, Innerhofer A, Binder C, Gizci H, Hammer K, Bruckdorfer A, Riedl S, Gadner H, Hirschl AM, Makristathis A. Stool polymerase chain reaction for Helicobacter pylori detection and clarithromycin susceptibility testing in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scaletsky IC, Aranda KR, Garcia GT, Gonçalves ME, Cardoso SR, Iriya K, Silva NP. Application of real-time PCR stool assay for Helicobacter pylori detection and clarithromycin susceptibility testing in Brazilian children. Helicobacter. 2011;16:311–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]