Abstract

Hot carriers (HC) generated by surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) in noble metals are promising for application in optoelectronics, plasmonics and renewable energy. However, existing models fail to explain key quantitative details of SPP-to-HC conversion experiments. Here we develop a quantum mechanical framework and apply first-principles calculations to study the energy distribution and scattering processes of HCs generated by SPPs in Au and Ag. We find that the relative positions of the s and d bands of noble metals regulate the energy distribution and mean free path of the HCs, and that the electron–phonon interaction controls HC energy loss and transport. Our results prescribe optimal conditions for HC generation and extraction, and invalidate previously employed free-electron-like models. Our work combines density functional theory, GW and electron–phonon calculations to provide microscopic insight into HC generation and ultrafast dynamics in noble metals.

Hot carriers generated by surface plasmons in metal structures are garnering interest for their use in optoelectronics or photocatalysis. Bernardi et al. present a quantum mechanical framework to study their properties and find the optimalyconditions for their generation and extraction.

Hot carriers generated by surface plasmons in metal structures are garnering interest for their use in optoelectronics or photocatalysis. Bernardi et al. present a quantum mechanical framework to study their properties and find the optimalyconditions for their generation and extraction.

Surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) are electron collective excitations generated by light at the interface between a metal and a dielectric1. Modelling of SPPs is dominated by approaches that employ classical electromagnetism and account empirically for the properties of the materials supporting the SPP. Yet, the inherently quantum mechanical nature of SPPs2,3 becomes manifest in their scattering and decay processes in bulk and nanoscale materials. A key example is the decay of SPPs to electron-hole pairs, a process whose crucial importance is twofold: first, it is a main energy loss mechanism of SPPs in metals, currently limiting the applicability of plasmonics4,5; second, it leads to generation of hot electrons and holes with application in several branches of applied physics6. Recent experiments reported the extraction of such SPP-induced hot carriers (HCs) in metals before they thermalize—typically over nanometer lengths and sub-picosecond times—by injecting the HCs over a Schottky barrier into a semiconductor or oxide7,8,9, or by transferring them into surface adsorbates to perform chemical reactions with large activation barriers6,10,11. The vast literature on HCs in noble metals generated by intense light pulses12,13,14 (instead of SPPs), together with recent calculations on SPP-to-HC conversion15,16, help interpret these recent experiments on SPP-induced HCs.

Lack of predictive and accurate quantum mechanical approaches to study HCs generated by SPPs or photons has led to ambiguity in the microscopic interpretation of experiments involving HCs in Au and Ag, two mainstay materials in plasmonics4. In particular, recent studies indicate that SPP decay excites electronic transitions from occupied states close to the Fermi energy (EF)10, implying that most of the SPP energy goes into hot electrons rather than hot holes, and that nanocrystals with <10 nm diameter are necessary to obtain HCs with significant energy17 (for example, 1–2 eV away from EF). The mean free paths (MFPs) of HCs in noble metals appear to be short10, though a quantitative estimate of the MFPs and their dependence on crystal direction is not available. In addition, it is often assumed that HC scattering and thermalization are dominated by Auger processes10,14, since thermalization induced by phonons occurs on a slower time scale14. As shown in this work, all these conclusions must be revised.

Here, we develop a quantum mechanical framework to study the energy distribution of HCs generated by SPPs and photons in Au and Ag, and employ ab initio calculations of the electron–phonon (e–ph) and electron-electron (e–e) interactions to study the MFPs and relaxation times of HCs within 5 eV of the Fermi energy. Our approach is free of experimental input, and combines density functional theory (DFT)18, the GW (where G is the Green function, W is the screened Coulomb potential, and GW is the diagram employed for the electron self energy) method19, and ab initio e–ph calculations20. Our ability to use extremely fine grids for Brillouin zone (BZ) integrations allows us to resolve HC scattering with unprecedented accuracy21. We find that the interband transition threshold (between d and s states) defines two regimes for HC generation and transport. The decay of SPPs with energy lower than the interband threshold leads to generation of long-lived HCs with long isotropic MFPs of up to 40 nm and energy within 1–2 eV of EF. On the other hand, decay of SPPs with energy higher than the interband threshold leads to generation of short-lived hot holes in d states with anisotropic and short (sub 5 nm) MFPs, and hot electrons with only <1 eV energy above EF. The regime characterized by SPP energy below the interband threshold is better suited to employ HCs in applications requiring long MFPs, and allows one to optimize HC generation by tuning the SPP energy. These results represent an important first step to understand SPP decay and energy loss, and to control HC generation and transport in bulk and nanostructured noble metals.

Results

Theory of SPP—electron coupling

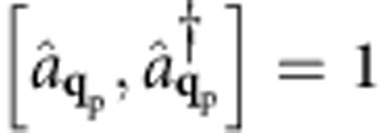

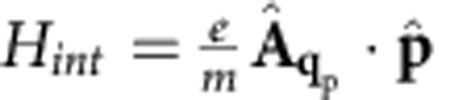

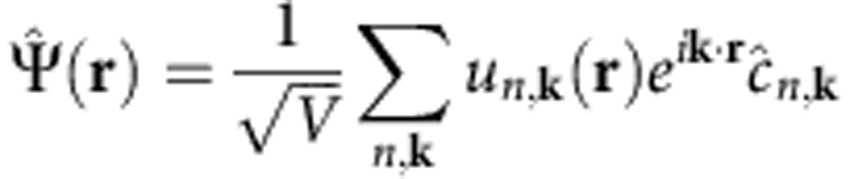

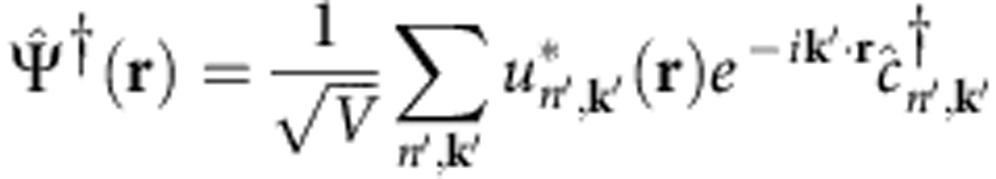

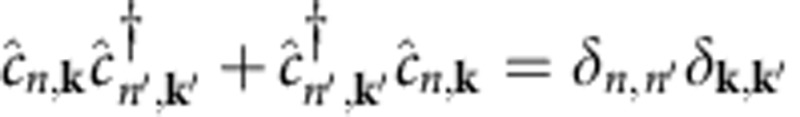

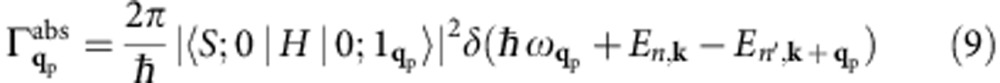

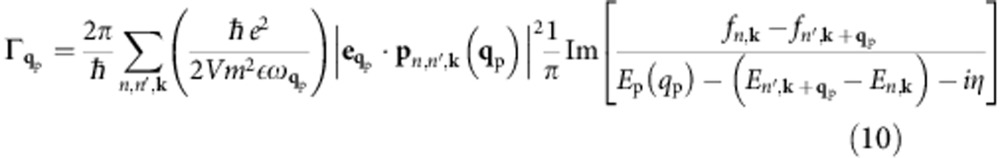

Coupling of SPPs or photons to electrons in materials can be described in the framework of many-body perturbation theory22. The lowest order Feynman diagram for this coupling process, shown in Table 1, describes a boson (here, SPP or photon) coupling to the electron gas through the electronic polarizability χ and a coupling matrix element g. This diagram is analogous to the lowest order coupling of phonons to electrons23,24. The decay rate Γ(qp,Ep) for a boson of momentum ħqp and energy EP to electron–hole pairs is proportional to the imaginary part of the self-energy22:

Table 1. Boson–electron coupling and matrix elements.

|

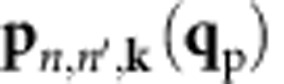

where −En,k and  are, respectively, the quasiparticle energies of the hot hole in a state with band n and crystal momentum –k, and hot electron in a state with band n′ and crystal momentum k+qp, as generated in the boson decay process. In addition, fn,k and

are, respectively, the quasiparticle energies of the hot hole in a state with band n and crystal momentum –k, and hot electron in a state with band n′ and crystal momentum k+qp, as generated in the boson decay process. In addition, fn,k and  are Fermi occupations, η is a small broadening, and the sum is contributed by electronic transitions from occupied to empty states that differ by ħqp in crystal momentum and Ep in energy. If the matrix elements have a weak band and k dependence, the decay rate of a SPP or photon is proportional to the imaginary part of the electronic polarizability, Imχ(qp,EP).

are Fermi occupations, η is a small broadening, and the sum is contributed by electronic transitions from occupied to empty states that differ by ħqp in crystal momentum and Ep in energy. If the matrix elements have a weak band and k dependence, the decay rate of a SPP or photon is proportional to the imaginary part of the electronic polarizability, Imχ(qp,EP).

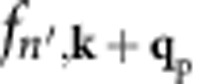

Here, we employ a quantity proportional to Imχ(qp,EP), the finite momentum joint density of states (FM-JDOS) J(qp,EP), defined as the number of states per unit energy separated by momentum ħqp and energy Ep in the quasiparticle bandstructure:

|

The FM-JDOS is a measure of the phase space available for the decay of a SPP or photon with momentum ħqp and energy Ep. Greater FM-JDOS values generally would correspond to greater SPP decay and HC generation rates.

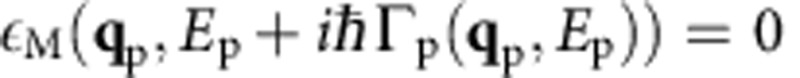

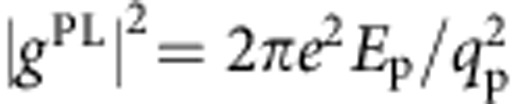

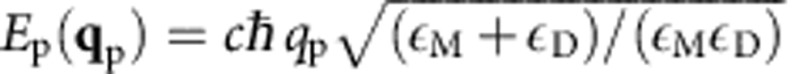

The coupling matrix elements in equation (1) can be derived with a range of theoretical approaches. We first discuss the coupling of electrons to plasmons—that is, collective electronic excitations in the absence of light—since theories developed for plasmons have been occasionally applied to SPPs25. The so-called Landau damping26 treatment of the electron gas derives the decay rate Γp of a bulk plasmon in the weak coupling limit via the zeros of the complex macroscopic dielectric function ɛM of the metal close to the real energy axis, that is,  . Due to the bosonic nature of plasmons, the decay rate Γ(qp,Ep) has the form given in equation (1), with coupling matrix elements26

. Due to the bosonic nature of plasmons, the decay rate Γ(qp,Ep) has the form given in equation (1), with coupling matrix elements26

. In spite of its common use, Landau damping is rarely discussed in terms of the diagram in Table 1 and the coupling gPL, though this viewpoint elucidates its physical origin.

. In spite of its common use, Landau damping is rarely discussed in terms of the diagram in Table 1 and the coupling gPL, though this viewpoint elucidates its physical origin.

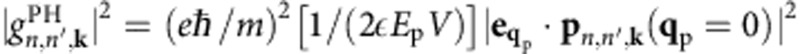

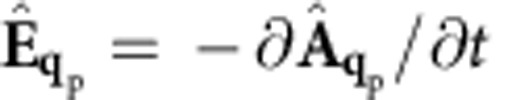

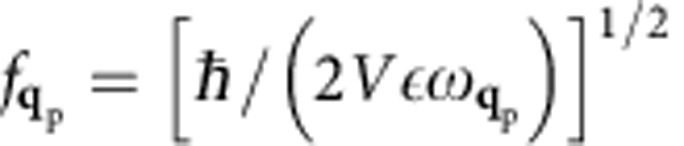

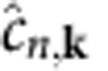

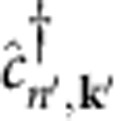

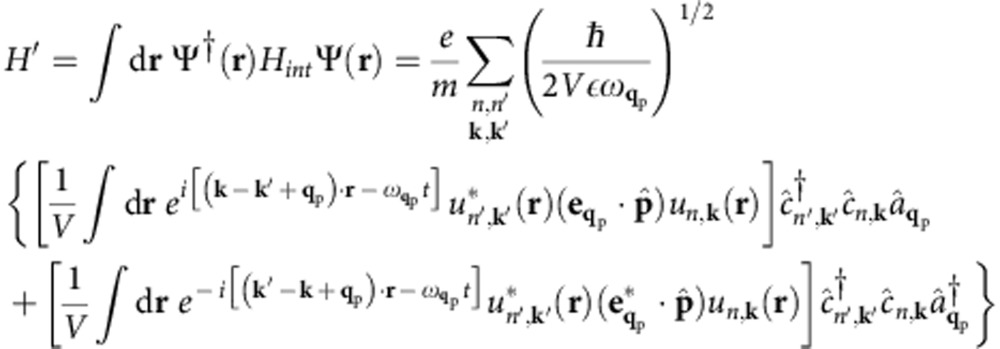

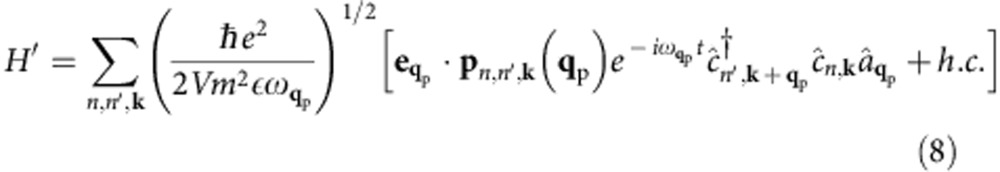

The coupling matrix elements for SPPs and photons can be derived by second quantization of the vector potential27 (see Methods). For photons, the coupling is given by the well-known dipole matrix element  , where V is the volume,

, where V is the volume,  is the polarization vector, and

is the polarization vector, and  the transition dipole matrix element. For SPPs at a metal–dielectric interface, we apply a vector potential second quantization procedure28,29 (see Methods) to obtain the SPP–electron coupling

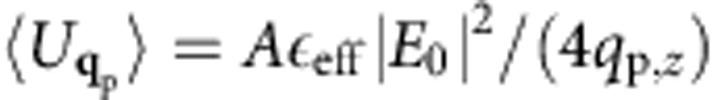

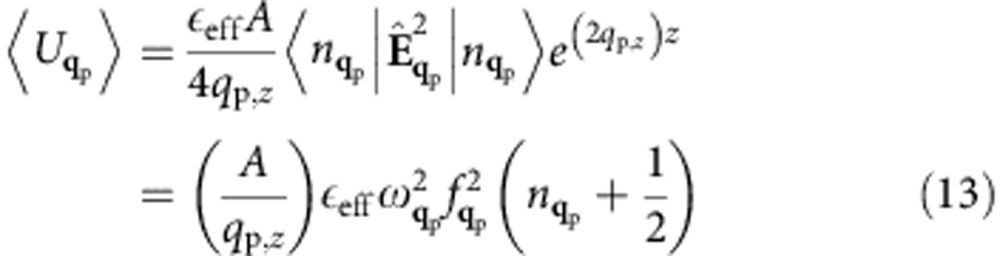

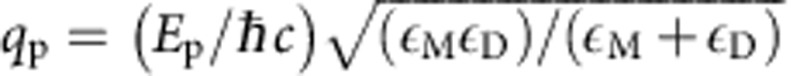

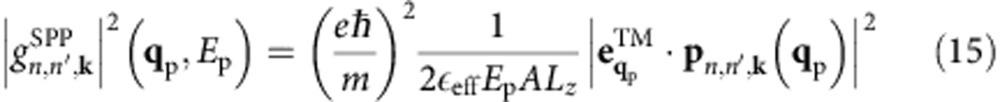

the transition dipole matrix element. For SPPs at a metal–dielectric interface, we apply a vector potential second quantization procedure28,29 (see Methods) to obtain the SPP–electron coupling  given in Table 1. The SPP–electron coupling has a form analogous to that for photons, with two important differences. First, the volume V is replaced by the SPP-field volume VSPP=A·Lz, where A is the metal–dielectric interface area and Lz the decay length of the SPP in the metal. Since Lz is of order 10 nm at visible wavelength for noble metals1 and thus much shorter than the light absorption depth, the electric field associated with the SPP is concentrated to a small volume VSPP at the metal–dielectric interface1, resulting in enhanced local generation of HCs from SPPs compared with light. Second, the SPP wavevector qp is in general comparable to the size of the BZ, while for photons qp≈0. The finite SPP wavevector can significantly alter the phase space available for SPP decay, as dictated by the qp dependence of the FM-JDOS. We remark that additional momentum can be transferred by phonons and defects assisting the SPP scattering process.

given in Table 1. The SPP–electron coupling has a form analogous to that for photons, with two important differences. First, the volume V is replaced by the SPP-field volume VSPP=A·Lz, where A is the metal–dielectric interface area and Lz the decay length of the SPP in the metal. Since Lz is of order 10 nm at visible wavelength for noble metals1 and thus much shorter than the light absorption depth, the electric field associated with the SPP is concentrated to a small volume VSPP at the metal–dielectric interface1, resulting in enhanced local generation of HCs from SPPs compared with light. Second, the SPP wavevector qp is in general comparable to the size of the BZ, while for photons qp≈0. The finite SPP wavevector can significantly alter the phase space available for SPP decay, as dictated by the qp dependence of the FM-JDOS. We remark that additional momentum can be transferred by phonons and defects assisting the SPP scattering process.

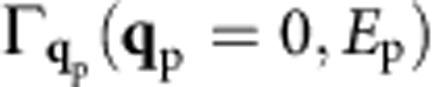

For both SPP and photon decay, the FM-JDOS regulates the phase space for HC generation. Since the experimental conditions and the material-specific SPP dispersion relation dictate the SPP energy Ep and wavevector qp1,30,31, we study the FM-JDOS as a function of qp and Ep and arbitrarily treat them for the purpose of this work as independent variables; HC generation from light is obtained as the specific limit qp=0. We note that the SPP decay rate Γp(qp,Ep) could also be computed by evaluating the coupling matrix elements explicitly for fixed experimental conditions and dispersion relation1

. This approach would enable first-principles calculations of plasmonic losses and the MFPs of SPPs in materials4,5.

. This approach would enable first-principles calculations of plasmonic losses and the MFPs of SPPs in materials4,5.

HC generation

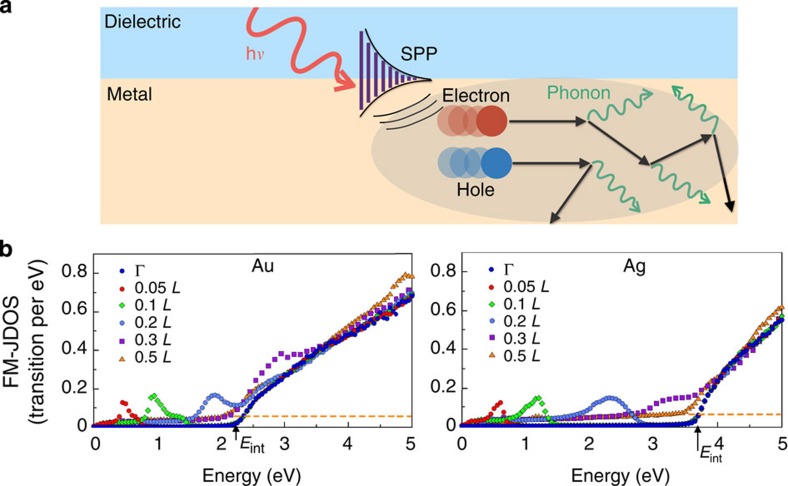

To study HC generation from SPPs at a metal–dielectric interface (see Fig. 1a), we compute the FM-JDOS for Au and Ag, as shown in Fig. 1b, for SPP energies up to 5 eV and increasing SPP wavevectors along the Γ–L direction in the BZ (that is, for SPPs propagating along the [111] crystallographic direction). Our calculations are carried out using GW bandstructures (see Methods).

Figure 1. Hot carrier generation in Au and Ag.

(a) Schematic of a metal–dielectric interface under illumination, showing the decay of a SPP to a pair of hot electron and hole. The hot carriers are scattered and lose energy through phonon emission processes. The mean free path corresponds to the length of the black arrows, and the excited volume within the metal is shaded in grey. (b) The FM-JDOS of Au (left panel) and Ag (right panel) as a function of SPP energy, shown for several values of qp along the Γ–L direction, up to a value of qp=0.5 L. The SPP wavevector is expressed in units of the L point in the BZ, where L=(π/a)(1,1,1), with a the lattice constant. The FM-JDOS for photons and SPPs with vanishingly small wavevector corresponds to the qp=0 case (curve labelled as Γ). The dashed lines indicate the value of the FM-JDOS low-energy tail for large wavevectors.

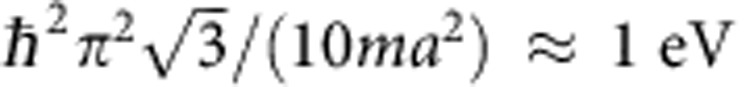

Detailed features of the bandstructures of Au and Ag, shown in Fig. 2, regulate HC generation and transport in these materials. The main features of the Au and Ag bandstructures are the presence of relatively dispersionless, occupied d bands with large associated electronic DOS, straddled by a free-electron-like s band. The top of the d bands is located at energy Eint below the Fermi energy, where Eint is the threshold for interband (d to s) electronic transitions32,33. From our GW calculations, we find Eint values of 2.3 eV in Au and 3.7 eV in Ag (see Fig. 2), in excellent agreement with experiment5,32,33. The free-electron-like s band spans an energy window between Eint below and over 4 eV above EF, and hence dominates the electronic properties of Au and Ag near EF.

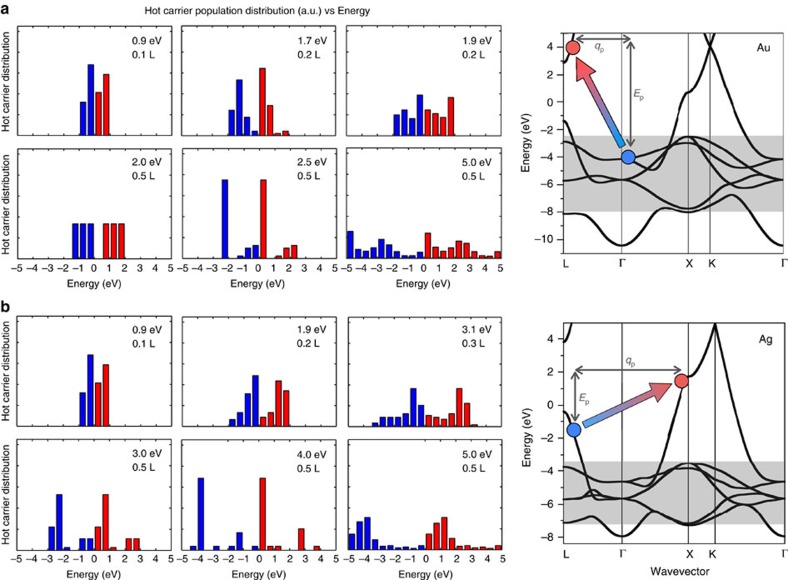

Figure 2. Energy distribution of hot carriers.

Energy distribution of hot electrons (red) and hot holes (blue) in Au (a) and Ag (b) generated by SPP decay. Each plot refers to a specific SPP energy and wavevector. The right panel shows the GW bandstructures of Au and Ag, respectively, in a and b, along with a schematic of the momentum and energy conserving excitation of a hot electron–hole pair resulting from the decay of a SPP with wavevector qp and energy Ep. The shaded area indicates the energy range of the d states. The energy difference between the Fermi energy and the top of the d bands corresponds to the interband transition threshold. The Fermi energy is the zero of the energy axis.

The FM-JDOS in Fig. 1b follows similar trends in Au and Ag, with deviations due to the different Eint values in the two materials. We first discuss the FM-JDOS with qp=0, which quantifies the phase space for HC generation for both SPPs with very small wavevectors and photons. The FM-JDOS curve with qp=0 (Γ) has a zero value for SPP energies up to Eint, indicating the absence of possible SPP decay into HCs in this energy range. For SPP energies greater than Eint, the FM-JDOS increases linearly with energy, indicating that a large phase space opens up for HC generation. In this regime, SPP damping is strong, and HC generation is intense and dominated by formation of hot d holes collecting most of the energy from the SPP, as discussed below.

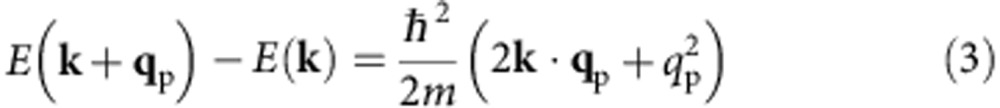

For small SPP wavevectors along the Γ–L direction up to ∼0.2L, we find a peak in the FM-JDOS corresponding to SPP decay through intraband transitions within the s band. The energy position of the peak increases linearly with SPP wavevector, and for large enough wavevectors merges with the FM-JDOS above Eint. In Au, the intraband peak is below Eint for qp values up to ∼0.2 L, and in Ag for qp values up to ∼0.3 L due to the higher Eint value in Ag. The presence of an intraband peak associated with s–s transitions can be understood by examining the energy difference between states with momentum k and k+qp in the free-electron-like s band:

|

For small wavevector qp, the term quadratic in qp can be neglected, while the term linear in qp increases by ∼ (a is the lattice constant) for an increase of qp by 1/10 the Γ–L distance. The computed FM-JDOS confirms these trends, as seen by the increase in the energy of the intraband peak by ∼1 eV in going from 0.1 L to 0.2 L and from 0.2 L to 0.3 L. In this small wavevector regime, generation of HCs is appreciable only if the SPP energy and wavevector are matched to the intraband FM-JDOS peak, namely if Ep(qp)≈(ℏ2k·qp)/m for a set of k points in the BZ. When this condition is met, intense HC generation from intraband transitions can occur, resulting in an almost equal apportioning of the SPP energy between hot electrons and holes, as discussed below.

(a is the lattice constant) for an increase of qp by 1/10 the Γ–L distance. The computed FM-JDOS confirms these trends, as seen by the increase in the energy of the intraband peak by ∼1 eV in going from 0.1 L to 0.2 L and from 0.2 L to 0.3 L. In this small wavevector regime, generation of HCs is appreciable only if the SPP energy and wavevector are matched to the intraband FM-JDOS peak, namely if Ep(qp)≈(ℏ2k·qp)/m for a set of k points in the BZ. When this condition is met, intense HC generation from intraband transitions can occur, resulting in an almost equal apportioning of the SPP energy between hot electrons and holes, as discussed below.

For SPP wavevectors larger than ∼0.3 L, the FM-JDOS resembles that for qp=0 except from a flat tail that extends to low SPP energy, as shown by the dashed lines in Fig. 1. This tail is due to generation of HCs from intraband transitions with large transferred momentum from the decay of SPPs with wavevector comparable to the size of the BZ. The FM-JDOS for qp>0.5 L is unchanged and nearly identical to the 0.5 L case.

To summarize, we find two HC generation regimes. For SPPs with energy Ep<Eint, optimal generation can be achieved using SPPs with relatively small wavevector (less than ∼1/5 the BZ size) that are matched with the FM-JDOS peak, while HC generation is relatively weak for SPPs with larger momentum. For SPPs with energy Ep>Eint, HC generation is intense regardless of the SPP momentum. We find identical trends for SPPs with wavevector in the Γ–X high-symmetry direction, that is, propagating along the [100] direction. Removal of the electron gas approximation used in simplified treatments of SPPs in noble metals17 is necessary to capture the delicate interplay found here between the energetics of the s and d states and intraband (s–s) and interband (d–s) transitions.

Energy distribution of HCs

Figure 2 shows the energy distribution of HCs generated by specifically assumed SPPs with energy increasing in small steps from ∼1 to 5 eV and a range of wavevectors in the Γ–L direction, along with the GW bandstructures. From now on throughout the manuscript, all HC energies are referenced to the Fermi energy (EF), and the energy of the hot hole is −E, that is, the direction of increasing energy in the bandstructure is downward for holes and upward for electrons. The energy distribution histograms identify the HCs generated in the two regimes discussed above. For SPPs with energy lower than Eint, hot holes and electrons are generated with a roughly uniform energy distribution as a result of the s–s intraband transitions. The HC energy distributions shown in Fig. 2 in this energy range pertain to SPPs with energy and wavevectors matched to the FM-JDOS intraband peaks (see Fig. 1). While the details of the energy distribution in this regime are sensitive to the SPP energy Ep, the overall trends indicate that HCs are generated with an average energy of ∼Ep/2.

For SPPs with energy greater than Eint, we find a change to a different HC generation regime. At the onset of the interband transitions for SPP energy of 2.3 eV in Au and 3.7 eV in Ag, on SPP decay the hot holes absorb most of the SPP energy, creating a spike in the hot hole population at the top of the d band. On the other hand, hot electrons have only modest energies in this regime. At higher SPP energies of ∼5 eV, the HC population become approximately uniformly distributed over a wide energy range, although a peak in the hot d hole population is still present in Ag due to its higher Eint. These trends are common to both Au and Ag, and we have verified that Cu, a material less commonly used in plasmonics5 and not discussed here, follows identical HC generation and energy distribution trends as Au and Ag.

HC scattering processes

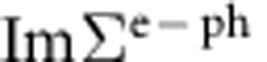

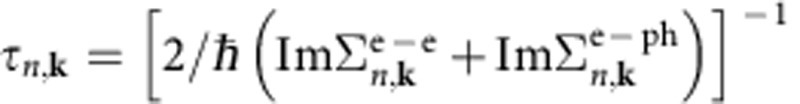

While ample experimental13,32 and theoretical14 data exists on HCs in noble metals, characterization of the MFPs and relaxation times of HCs using ab initio theory has been limited by the absence of accurate e–ph calculations including all phonon modes over the entire BZ. First-principles calculations combining e–ph and e–e interactions are necessary to characterize the anisotropic and energy-dependent MFPs of HCs in materials, as shown in our recent work on HCs in semiconductors21. We compute the scattering rate (and its inverse, the relaxation time) for the e–ph and e–e interactions from the imaginary part of the respective self-energies,  and

and  , and resolve these quantities for each electronic state with band n and k-point on very fine BZ grids (see Methods and ref. 21). The total relaxation times τn,k, combining the e–ph and e–e interactions, are obtained as

, and resolve these quantities for each electronic state with band n and k-point on very fine BZ grids (see Methods and ref. 21). The total relaxation times τn,k, combining the e–ph and e–e interactions, are obtained as  .

.

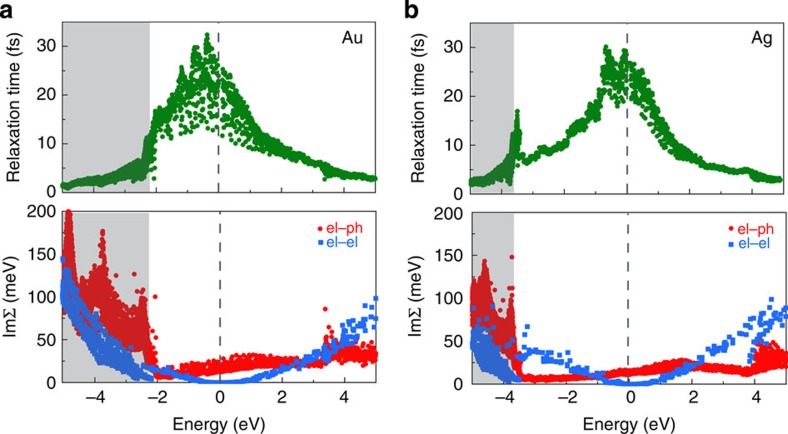

Figure 3 shows the total relaxation times τn,k for HCs in Au and Ag with energy up to 5 eV. The total relaxation times decay rapidly away from EF following a volcano-shaped trend, with the peak of the volcano centred close to EF. In Ag, we find an additional peak in the relaxation times at the top of the d bands, in agreement with recent photoemission experiments34. Analysis of the e–ph and e–e scattering rates (see the bottom panels in Fig. 3) highlights the differences between the energy windows spanned by the s and d states, and elucidates the origin of the relaxation time trends. In the energy range spanned by the s states, the e–e scattering rates (that is,  ) form a parabola with minimum value of zero at EF as predicted by Fermi liquid theory14, while the e–ph scattering rates are relatively constant and exhibit a minimum at the onset of the d states and a maximum 1–2 eV above EF. The e–e scattering rates become greater than the e–ph ∼2 eV away from EF, thus indicating that Auger and impact ionization processes included in the e–e term dominate HC scattering only 2 eV or more away from EF, while e–ph dominates HC scattering within 2 eV of EF. Combining the two scattering mechanisms leads to total relaxation times with a broad maximum centred at EF and a rapid decay 1–2 eV away from EF as the parabolic e–e scattering rate becomes dominant (see Fig. 3). In the energy window spanned by the d bands, the large increase in the electronic DOS causes very strong e–ph scattering, and the localized nature of the d states leads to deviations from the free-electron parabolic trends for e–e scattering. The total relaxation times show that hot holes arising from d states lose energy on a sub-5-fs time scale, thus making such hot d holes challenging to extract before thermalization. Finally, our calculations yield comparable time scale and scattering rate for e–ph and e–e scattering, in contrast with the common heuristic assumption that scattering by phonons occurs on a much slower time scale14. We thus conclude that previous models including only e–e scattering14 and missing the important e–ph component are incomplete for understanding HC relaxation times and photoemission linewidths in noble metals.

) form a parabola with minimum value of zero at EF as predicted by Fermi liquid theory14, while the e–ph scattering rates are relatively constant and exhibit a minimum at the onset of the d states and a maximum 1–2 eV above EF. The e–e scattering rates become greater than the e–ph ∼2 eV away from EF, thus indicating that Auger and impact ionization processes included in the e–e term dominate HC scattering only 2 eV or more away from EF, while e–ph dominates HC scattering within 2 eV of EF. Combining the two scattering mechanisms leads to total relaxation times with a broad maximum centred at EF and a rapid decay 1–2 eV away from EF as the parabolic e–e scattering rate becomes dominant (see Fig. 3). In the energy window spanned by the d bands, the large increase in the electronic DOS causes very strong e–ph scattering, and the localized nature of the d states leads to deviations from the free-electron parabolic trends for e–e scattering. The total relaxation times show that hot holes arising from d states lose energy on a sub-5-fs time scale, thus making such hot d holes challenging to extract before thermalization. Finally, our calculations yield comparable time scale and scattering rate for e–ph and e–e scattering, in contrast with the common heuristic assumption that scattering by phonons occurs on a much slower time scale14. We thus conclude that previous models including only e–e scattering14 and missing the important e–ph component are incomplete for understanding HC relaxation times and photoemission linewidths in noble metals.

Figure 3. Ultrafast hot carrier scattering.

Relaxation time and scattering rates for HCs in Au (a) and Ag (b) within 5 eV of the Fermi energy. The top panels show the total relaxation time, accounting for both the e–e and the e–ph interactions. The bottom panels show the scattering rate, expressed as the imaginary part of the self-energy,  , for the e–e and e–ph interactions. EF is the zero of the energy axis, as shown by the dashed line. Electrons (holes) possess positive (negative) energies, and the shaded area indicates the energy window spanned by the d states.

, for the e–e and e–ph interactions. EF is the zero of the energy axis, as shown by the dashed line. Electrons (holes) possess positive (negative) energies, and the shaded area indicates the energy window spanned by the d states.

To validate our results, we compare our relaxation times at the Fermi energy in Au and Ag with those inferred from carrier transport measurements. Kopitzki35 combined the Drude model with room temperature resistivity measurements, and obtained semiempirical relaxation times of 29 fs for Au and 41 fs for Ag, in close agreement with those obtained by Ashcroft and Mermin36 with the same approach. Averaging our relaxation times over a small energy window around EF yields relaxation times of 24 fs for Au and 27 fs for Ag. While the agreement is excellent for Au and good for Ag, our data shows a large spread in the relaxation times at EF, a feature not captured by the Drude model and stemming from the Fermi surface anisotropy. It is therefore puzzling that the Drude relaxation times33,35 are widely used in plasmonics4,5, given that their physical meaning is questionable when applied to non-equilibrium situations involving SPPs. We conclude that further investigation on this point is necessary, and remark that ours is the first truly ab initio determination of the relaxation times on the Fermi surface of noble metals, to be discussed in detail elsewhere.

HC MFP

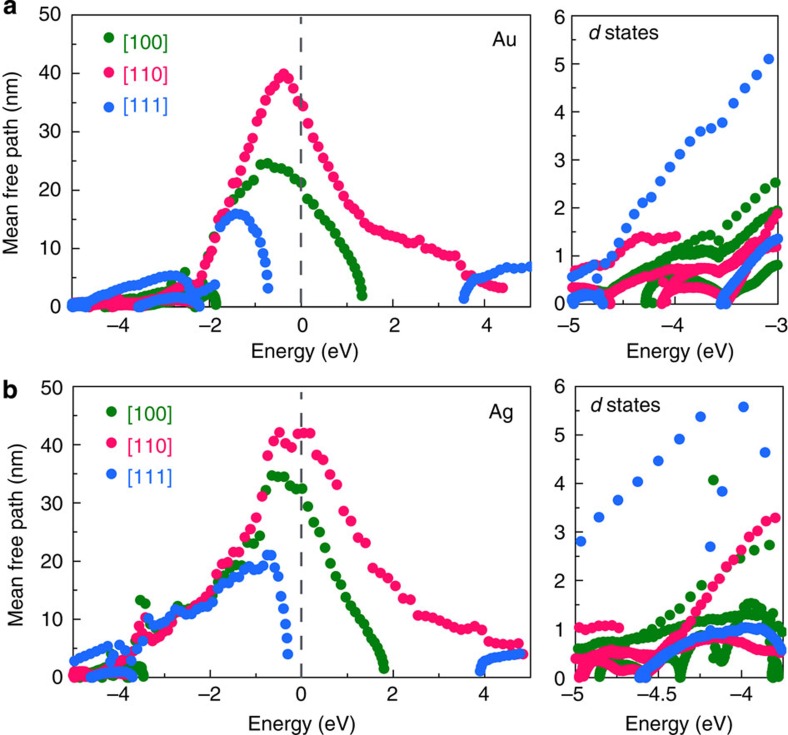

Next, we turn our attention to HC transport. Figure 4 shows the MFP for the three crystallographic directions [100], [110] and [111] within 5 eV of the Fermi energy. The MFPs are obtained by multiplying the total relaxation times by the carrier velocities computed from the slope of the GW bandstructures (see Methods). Our computed MFPs are of the order 10–40 nm in the energy window spanned by the s states, and much shorter (1–5 nm) for the d states. The MFPs of the s states exhibit an energy dependence with the volcano shape also seen in the relaxation times, with deviations coming from the different band velocities along each direction. The MFPs of hot holes with 1–2 eV energy are nearly isotropic, while the MFPs of hot holes with <1 eV energy are longer for the [100] and [110] directions. The MFPs of hot electrons are highly anisotropic due to the absence of electronic states up to 4 eV above EF in the [111] direction and at energy >1–2 eV in the [100] direction. The longest hot electron MFPs are in the [110] direction up to 4 eV above EF. We note that the energy derivative of the MFPs at EF at is negative, consistent with the positive thermopower in Au and Ag37. In the energy window spanned by the d states, the MFPs are of order 5 nm in the [111] direction and 1 nm in the other directions, and thus highly anisotropic with longer MFPs in the [111] direction. The isotropic MFPs for s holes and anisotropic for d holes are consistent with findings in ballistic electron energy microscopy experiments in noble metals, where it was found that d holes injected by a scanning tunneling microscope tip propagate along narrow cones and span small volumes, while s holes span large volumes isotropically38.

Figure 4. Hot carrier mean free path.

The hot carrier MFPs along the [100], [110] and [111] crystallographic directions in Au (a) and Ag (b). The MFPs for the d states are expanded in the right panels.

Discussion

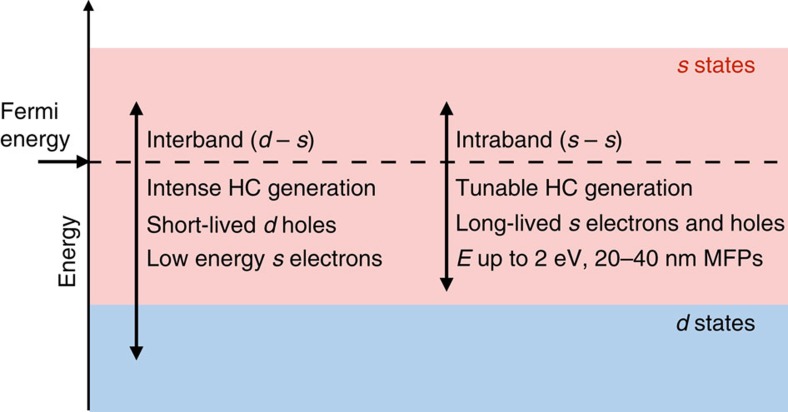

The data obtained so far allow us to formulate optimal conditions to generate HCs and extract or utilize them before thermalization. Figure 5 summarizes HC generation and transport in Au and Ag by defining two regimes for HC generation from intraband (Ep<Eint) and interband (Ep>Eint) transitions induced by SPP decay. The energy distribution, relaxation time and MFP of the generated HCs are dramatically different in these two regimes. For Ep<Eint, the HCs consist of s holes and s electrons with average energies up to Eint/2 (that is, 1–2 eV) generated by weakly damped SPPs due to the small FM-JDOS values. HC generation can be optimized by matching the energy and momentum of the SPP to the FM-JDOS intraband peak described above and shown in Fig. 1. The HCs in this energy range possess relatively long MFPs of ∼10–40 nm, and can thus be extracted before thermalization over ∼50 nm lengths in ideally pure samples. This regime is thus optimal for HC generation and extraction. For hot electrons, we predict that the (110) surface would be best suited to extract HCs due to the longer MFPs in the [110] direction. For hot holes with ∼1–2 eV energy, the (100) and (110) surfaces are predicted to enable optimal extraction. Our results further suggest that Ag may be better suited than Au for HC generation due to the wider energy window for intraband transitions, thus motivating studies of HC generation from SPPs in Ag. On the other hand, the strong SPP damping regime with Ep>Eint is non-optimal for extracting HCs, since in spite of strong HC generation the SPP energy is mostly transferred to short-lived hot d holes with ∼1 nm MFP, while hot electrons possess only low energy of <1 eV. These conditions prevent HC extraction in this regime, unless a nanometer-thick thin film or nanostructured metal is employed.

Figure 5. Regimes for hot carrier generation and transport in noble metals.

The graph shows two HC generation regimes, for intraband (s–s) and interband (d–s) transitions induced by SPPs with energy Ep<Eint or Ep>Eint, respectively. The regime with Ep<Eint offers a trade-off between optimal HC generation, moderate HC energies up to ∼2 eV, and longer MFPs and relaxation times than the interband regime. The dashed line indicates the Fermi energy.

Our data further show that nanostructuring the metal to sub-10-nm size is not required to obtain energetic HCs, and not needed to extract them unless HCs with >2 eV energy are desired. In addition, for SPP with energy lower than Eint, the SPP energy is equally distributed between hot electrons and holes, and energy loss is dominated by e–ph rather than Auger scattering. These findings address the misconceptions emerged in recent work as outlined above, and show that optimal HC generation is possible by carefully tuning the SPP energy and wavevector at noble metal–dielectric interfaces. Finally, we note that our approach is for now limited to SPP at metal–dielectric interfaces, while localized surface plasmons in nanostructures need to be treated differently due to their localized nature39. We believe that the method presented in this work can be extended to study HC generation from localized surface plasmon modes, which will be the subject of future investigation.

In summary, we establish a theoretical framework to study SPP damping and HC generation and transport on the same footing using many-body perturbation theory. Our first-principles calculations can accurately describe SPP-induced generation and ultrafast scattering of HCs in noble metals of use in plasmonics, photocatalysis, photovoltaics and optoelectronics. Our work highlights the interplay of the s and d bands in noble metals, and prescribe optimal experimental conditions for generation and extraction of HCs. Our approach paves the way to first-principles calculations of SPP losses in materials4.

Methods

First-principles calculations

We carry out ab initio calculations on Au, Ag and Cu in the face-centred cubic structure with lattice parameters of 7.72, 7.71 and 6.82 bohr, respectively. The ground-state electronic structure is computed within the local density approximation (LDA)40 of DFT using the QUANTUM ESPRESSO code41. We use norm-conserving pseudopotentials (which include semicore s and p states) to describe the core-valence interaction42, together with a plane-wave basis set with kinetic energy cutoff of 60 Ry for Ag and Au, and 240 Ry for Cu. The e–e (that is, GW) and e–ph self-energies are computed separately, and then combined together.

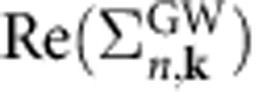

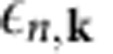

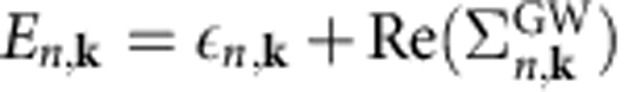

The real and imaginary parts of the GW self-energy19 are computed using the Berkeley-GW code43. The real part  is obtained with a generalized plasmon–pole calculation19 on a 12 × 12 × 12 k-point grid and then interpolated using Wannier functions (see below). Kinetic energy cutoffs of 50 Ry and 120 Ry are used, respectively, for the screened and bare Coulomb interactions, together with ∼1,000 empty bands and a 8 × 8 × 8 q-point grid for the dielectric screening. The DFT eigenvalues

is obtained with a generalized plasmon–pole calculation19 on a 12 × 12 × 12 k-point grid and then interpolated using Wannier functions (see below). Kinetic energy cutoffs of 50 Ry and 120 Ry are used, respectively, for the screened and bare Coulomb interactions, together with ∼1,000 empty bands and a 8 × 8 × 8 q-point grid for the dielectric screening. The DFT eigenvalues  are corrected with GW self-energies to obtain the quasiparticle bandstructures,

are corrected with GW self-energies to obtain the quasiparticle bandstructures,  , used in all calculations in this work. The imaginary part of the GW self-energy,

, used in all calculations in this work. The imaginary part of the GW self-energy,  , is computed using full-frequency GW calculations43. Here

, is computed using full-frequency GW calculations43. Here  are evaluated on-shell at the LDA eigenvalues

are evaluated on-shell at the LDA eigenvalues  , and then plotted versus the corresponding GW eigenvalues En,k. We use 20 × 20 × 20 k-point grids to converge

, and then plotted versus the corresponding GW eigenvalues En,k. We use 20 × 20 × 20 k-point grids to converge  within ∼10 meV. In addition, we use kinetic energy cutoffs of 20 Ry and 120 Ry, respectively, for the screened and bare Coulomb interactions, together with ∼100 empty bands and a 20 × 20 × 20 q-point grid for the dielectric screening.

within ∼10 meV. In addition, we use kinetic energy cutoffs of 20 Ry and 120 Ry, respectively, for the screened and bare Coulomb interactions, together with ∼100 empty bands and a 20 × 20 × 20 q-point grid for the dielectric screening.

The imaginary part of the e–ph self-energy,  , is computed using the EPW code20. We compute the self-consistent potential and Kohn–Sham states on a 12 × 12 × 12 k-point grid using DFT, and lattice-dynamical properties with DFPT44 on a 4 × 4 × 4 q-point grid. The e–ph matrix elements are first computed on these coarse grids, and then obtained on significantly finer grids using an interpolation procedure based on Wannier functions as implemented in the EPW code20,24. Maximally localized Wannier functions45 are obtained starting from five d orbitals on the metal atoms and two s orbitals, each in a tetrahedral interstitial point of the face-centred cubic lattice, for a total of seven wannierized bands (we skip the semicore states). The Wannier interpolated and DFT bandstructures agree within 5 meV in an energy window up to 5 eV above the Fermi energy. The Bloch-to-Wannier rotation matrices are then used to interpolate the GW bandstructures, which are used to compute

, is computed using the EPW code20. We compute the self-consistent potential and Kohn–Sham states on a 12 × 12 × 12 k-point grid using DFT, and lattice-dynamical properties with DFPT44 on a 4 × 4 × 4 q-point grid. The e–ph matrix elements are first computed on these coarse grids, and then obtained on significantly finer grids using an interpolation procedure based on Wannier functions as implemented in the EPW code20,24. Maximally localized Wannier functions45 are obtained starting from five d orbitals on the metal atoms and two s orbitals, each in a tetrahedral interstitial point of the face-centred cubic lattice, for a total of seven wannierized bands (we skip the semicore states). The Wannier interpolated and DFT bandstructures agree within 5 meV in an energy window up to 5 eV above the Fermi energy. The Bloch-to-Wannier rotation matrices are then used to interpolate the GW bandstructures, which are used to compute  . The fine grids for the calculation of

. The fine grids for the calculation of  consist in a 40 × 40 × 40 k-point grid, and up to 1 million random phonon q-points in the BZ. Such fine grids allow us to converge

consist in a 40 × 40 × 40 k-point grid, and up to 1 million random phonon q-points in the BZ. Such fine grids allow us to converge  within 1 meV. Further details of our approach to compute the e–ph self-energy are discussed in ref. 21.

within 1 meV. Further details of our approach to compute the e–ph self-energy are discussed in ref. 21.

The FM-JDOS calculations are carried out using Wannier interpolated GW bandstructures, a 100 × 100 × 100 k-point grid and a small Lorentzian broadening η≈25 meV. The energy distribution of the generated HCs in Fig. 2 are obtained by counting the momentum- and energy-conserving transitions in equation (2) as a function of occupied band (for hot holes) and empty band (for hot electrons) quasiparticle energies.

The MFPs are obtained using velocities computed from the slope of the GW bandstructure along the given high-symmetry direction, together with total relaxation times τn,k combining the e–ph and e–e relaxation times with Matthiessen's rule. The total relaxation times are obtained from  computed on grids of over 100 k points along each high-symmetry direction, and

computed on grids of over 100 k points along each high-symmetry direction, and  computed on a 20 × 20 × 20 k-grid and then averaged over k points to generate an energy-dependent

computed on a 20 × 20 × 20 k-grid and then averaged over k points to generate an energy-dependent  evaluated at each energy En,k for which a calculation of

evaluated at each energy En,k for which a calculation of  is performed.

is performed.

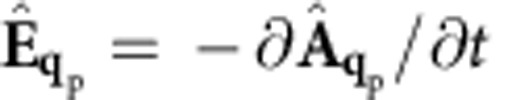

Derivation of the coupling matrix elements

The derivation of the plasmon-electron matrix element in Table 1 within the Landau damping approximation is given in ref. 26 and will not be discussed. Here we derive the coupling matrix elements for the photon–electron and SPP–electron interactions given in Table 1. We use SI units throughout the derivations. The photon case is well known27 and discussed here as a starting point for the SPP case. The second quantized vector potential  for a photon with momentum ħqp, energy

for a photon with momentum ħqp, energy  and polarization unit vector

and polarization unit vector  can be obtained by associating the amplitude with a destruction operator

can be obtained by associating the amplitude with a destruction operator  and its complex conjugate with a creation operator

and its complex conjugate with a creation operator  . We use the vector potential with unit amplitude since we are interested in the coupling matrix element, and thus the transition rate per unit of incident power. It reads27:

. We use the vector potential with unit amplitude since we are interested in the coupling matrix element, and thus the transition rate per unit of incident power. It reads27:

|

where  is a normalization constant. Using the Coulomb gauge

is a normalization constant. Using the Coulomb gauge  , the second quantized electric field can be obtained from

, the second quantized electric field can be obtained from  .

.

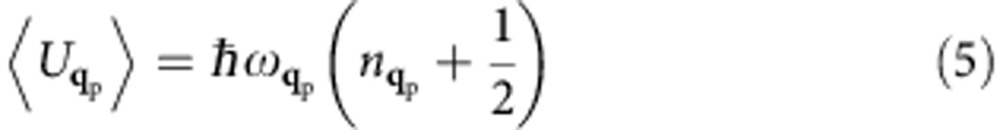

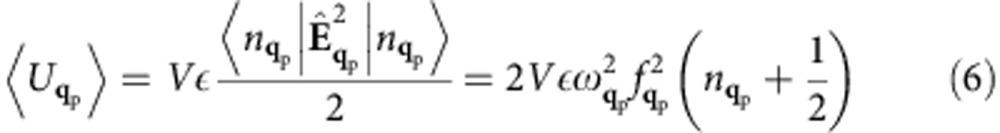

The normalization constant  is determined by equating the energy of the classical and quantized fields. The classical (cycle averaged) energy

is determined by equating the energy of the classical and quantized fields. The classical (cycle averaged) energy  for a photon with momentum ħqp in a homogeneous and isotropic material with dielectric constant

for a photon with momentum ħqp in a homogeneous and isotropic material with dielectric constant  is

is  , where V is the volume of the material. This energy needs to be equal to its quantum counterpart,

, where V is the volume of the material. This energy needs to be equal to its quantum counterpart,  . In addition,

. In addition,  can be obtained by averaging the quantized electric field

can be obtained by averaging the quantized electric field  over the quantum state

over the quantum state  with

with  photons. We get:

photons. We get:

|

|

where in the last equation we used the time derivative of equation (4) the electric field and the commutation rules for boson creation and annihilation operators,  . Equating equations (5) and (6) yields a normalization constant

. Equating equations (5) and (6) yields a normalization constant  , and a vector potential:

, and a vector potential:

|

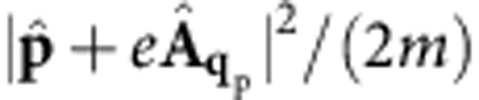

The photon–electron interaction Hamiltonian is  , as obtained by expanding the kinetic energy

, as obtained by expanding the kinetic energy  to first order in the vector potential. The second quantized fields associated with the electronic Bloch states are:

to first order in the vector potential. The second quantized fields associated with the electronic Bloch states are:

|

|

where  and

and  are, respectively, fermion annihilation and creation operators satisfying the anticommutation rule

are, respectively, fermion annihilation and creation operators satisfying the anticommutation rule  . The second quantized interaction Hamiltonian can be written as:

. The second quantized interaction Hamiltonian can be written as:

|

Crystal momentum conservation requires k′=±qp, where the plus and minus sign apply for the first and second integral above, respectively. The interacting Hamiltonian becomes:

|

where h.c. is the hermitian conjugate, and we defined the momentum matrix element as the integral  over the unit cell volume Ω, as commonly used in the study of optical absorption46. We obtain the photon decay rate

over the unit cell volume Ω, as commonly used in the study of optical absorption46. We obtain the photon decay rate  by applying Fermi's golden rule. Photon absorption occurs with a transition rate

by applying Fermi's golden rule. Photon absorption occurs with a transition rate  between an initial state

between an initial state  , consisting of the ground electronic state at room temperature and one photon with momentum qp, and a final state |S;0〉 with an electron in the Bloch state |n′,k+qp〉, a hole in the Bloch state |n,k〉 and no photons. The absorption rate is given by:

, consisting of the ground electronic state at room temperature and one photon with momentum qp, and a final state |S;0〉 with an electron in the Bloch state |n′,k+qp〉, a hole in the Bloch state |n,k〉 and no photons. The absorption rate is given by:

|

Only the first term in equation (8) gives a non-zero contribution, and we get:

|

The inverse process of photon emission from an initial state |S;0〉 to a final state  has a rate

has a rate  given by:

given by:

|

The net rate  is the decay rate of a photon with momentum ħqp and energy

is the decay rate of a photon with momentum ħqp and energy  into a hot electron–hole pair. Writing the delta function as a Lorentzian with broadening η→0, namely

into a hot electron–hole pair. Writing the delta function as a Lorentzian with broadening η→0, namely  , we obtain the decay rate as:

, we obtain the decay rate as:

|

This expression is identical to equation (1) with the squared coupling matrix elements  in Table 1. Since for photons qp≈0 compared with the size of the BZ, the squared coupling matrix elements are:

in Table 1. Since for photons qp≈0 compared with the size of the BZ, the squared coupling matrix elements are:

|

as shown in Table 1. We note that for slowly varying matrix elements in the BZ, the photon decay rate is proportional to the zero-momentum JDOS commonly used in the theory of the optical properties of solids 46, that is,  .

.

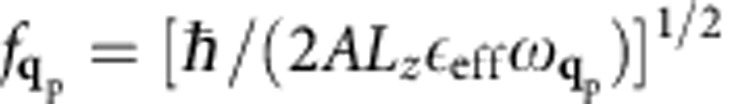

The derivation of the coupling matrix elements  for SPPs follows similar steps to the photon case discussed above. Following Nkoma et al.28, we study the case of a SPP generated at the interface between a metal with frequency-dependent dielectric function

for SPPs follows similar steps to the photon case discussed above. Following Nkoma et al.28, we study the case of a SPP generated at the interface between a metal with frequency-dependent dielectric function  and a dielectric material with frequency-independent dielectric constant

and a dielectric material with frequency-independent dielectric constant  . A similar second quantization procedure was also developed by Elson et al.29. It is well known that the intensity of the SPP wave decays exponentially in the direction perpendicular to the dielectric-metal interface1,30. To study HC generation, we focus here on the SPP field in the metal, and its associated vector potential. Since SPP possess transverse magnetic polarization, their wavevector can be taken as real in the xy plane—here the plane of the metal–dielectric interface, with area A—and purely imaginary in the z direction normal to the interface. With the metal in the z>0 space and the x-axis parallel to the propagation direction of the SPP wave, the SPP wavevector is qp=(qp,x,0,iqp,z). While in the main text, we define qp=(qp,x,0,0) as the propagation wavevector in the xy plane, for the purpose of this derivation qp is defined differently. Here qp,x is a real positive number since the electron-induced dissipation effects we aim to find would be encoded in its imaginary part, and qp,z is related to the decay length Lz of the SPP field intensity by30

qp,z=1/(2Lz). The relative magnitude of the components of qp are determined by the dielectric properties of the metal and dielectric1,30, which impose

. A similar second quantization procedure was also developed by Elson et al.29. It is well known that the intensity of the SPP wave decays exponentially in the direction perpendicular to the dielectric-metal interface1,30. To study HC generation, we focus here on the SPP field in the metal, and its associated vector potential. Since SPP possess transverse magnetic polarization, their wavevector can be taken as real in the xy plane—here the plane of the metal–dielectric interface, with area A—and purely imaginary in the z direction normal to the interface. With the metal in the z>0 space and the x-axis parallel to the propagation direction of the SPP wave, the SPP wavevector is qp=(qp,x,0,iqp,z). While in the main text, we define qp=(qp,x,0,0) as the propagation wavevector in the xy plane, for the purpose of this derivation qp is defined differently. Here qp,x is a real positive number since the electron-induced dissipation effects we aim to find would be encoded in its imaginary part, and qp,z is related to the decay length Lz of the SPP field intensity by30

qp,z=1/(2Lz). The relative magnitude of the components of qp are determined by the dielectric properties of the metal and dielectric1,30, which impose  (here, the real parts of

(here, the real parts of  and

and  should be employed for consistency). Similarly, the components of the unit polarization vector

should be employed for consistency). Similarly, the components of the unit polarization vector  are related by30

are related by30

.

.

The vector potential of the SPP wave in the metal, with unit amplitude as in the photon case, can be written in second quantized form as:

|

where, as in the photon case, the normalization constant  can be determined by energy considerations. We write the classical electric field associated with the SPP in the metal as

can be determined by energy considerations. We write the classical electric field associated with the SPP in the metal as  . Using a result in ref. 28, the cycle-averaged energy in the SPP field—which accounts for contributions from both the field in the dielectric and the metal—can be written as

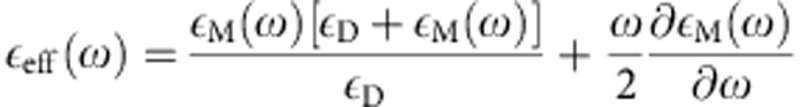

. Using a result in ref. 28, the cycle-averaged energy in the SPP field—which accounts for contributions from both the field in the dielectric and the metal—can be written as  , where we defined an effective dielectric constant:

, where we defined an effective dielectric constant:

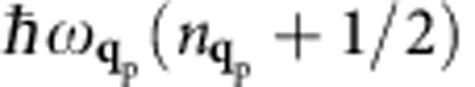

We use the correspondence principle for a quantum state  with

with  SPP quanta. Similar to the photon case, the total energy in the SPP mode

SPP quanta. Similar to the photon case, the total energy in the SPP mode  can be equated to its classical counterpart, while the square modulus of the electric field

can be equated to its classical counterpart, while the square modulus of the electric field  can be replaced with its quantum mechanical average

can be replaced with its quantum mechanical average  , with

, with  . We obtain the two equations:

. We obtain the two equations:

|

|

By equating equations (12) and (13), and using qp,z=1/(2Lz), we obtain the normalization constant  , and thus the SPP vector potential:

, and thus the SPP vector potential:

|

This vector potential is similar to the photon case, equation (7). The key differences are the decay in the z direction for the SPP field, which introduces an effective SPP volume ALz in the vector potential, the appearance of an effective dielectric constant for the medium and the fact that the polarization is transverse magnetic with a direction imposed by the properties of the metal and dielectric material.

Since the form of the SPP vector potential is completely analogous to the one for photons, the decay rate of SPPs to hot electron–hole pairs can be carried out following the same steps as in the photon case discussed above, with the substitutions V→ALz,  , and allowing for a finite momentum1

qp with magnitude

, and allowing for a finite momentum1

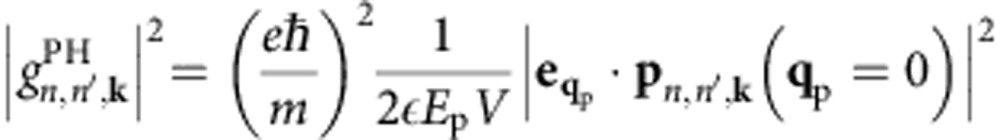

qp with magnitude  . This leads to the SPP–electron coupling matrix element in Table 1:

. This leads to the SPP–electron coupling matrix element in Table 1:

|

Additional information

How to cite this article: Bernardi, M. et al. Theory and computation of hot carriers generated by surface plasmon polaritons in noble metals. Nat. Commun. 6:7044 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8044 (2015).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the SciDAC Program on Excited State Phenomena in Energy Materials funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences and by the Advanced Scientific Computing Research, under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory which provided for algorithm and code developments and simulations; and by the National Science Foundation under grant DMR 10-1006184 which provided for basic theory and formalism. Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences and by the the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy.

Footnotes

Author contributions M.B. and J.M. carried out the calculations. All authors conceived the research and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Barnes W. L., Dereux A. & Ebbesen T. W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424, 824–830 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tame M. et al. Quantum plasmonics. Nat. Phys. 9, 329–340 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Fakonas J. S., Lee H., Kelaita Y. A. & Atwater H. A. Two-plasmon quantum interference. Nat. Photonics 8, 317–320 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- West P. R. et al. Searching for better plasmonic materials. Laser Photonics Rev. 4, 795–808 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Khurgin J. B. & Boltasseva A. Reflecting upon the losses in plasmonics and metamaterials. MRS Bull. 37, 768–779 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Brongersma M. L., Halas N. J. & Nordlander P. Plasmon-induced hot carrier science and technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 25–34 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavero C. Plasmon-induced hot-electron generation at nanoparticle/metal-oxide interfaces for photovoltaic and photocatalytic devices. Nat. Photonics 8, 95–103 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Chalabi H. & Brongersma M. L. Plasmonics: harvest season for hot electrons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 229–230 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisdale W. A. et al. Hot-electron transfer from semiconductor nanocrystals. Science 328, 1543–1547 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. et al. Hot electrons do the impossible: Plasmon-induced dissociation of H2 on Au. Nano Lett. 13, 240–247 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linic S., Christopher P. & Ingram D. B. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nat. Mater. 10, 911–921 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischkorn C. & Wolf M. Femtochemistry at metal surfaces: nonadiabatic reaction dynamics. Chem. Rev. 106, 4207–4233 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallée F. Ultrafast spectroscopy of metals. C. R. Acad. Sci. Ser. IV Phys. 2, 1469–1482 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Echenique P., Pitarke J., Chulkov E. & Rubio A. Theory of inelastic lifetimes of low-energy electrons in metals. Chem. Phys. 251, 1–35 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaman R., Narang P., Jermyn A. S., Goddard W. A. III & Atwater H. A. Theoretical predictions for hot-carrier generation from surface plasmon decay. Nat. Commun. 5, 5788 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjavacas A., Liu J. G., Kulkarni V. & Nordlander P. Plasmon-induced hot carriers in metallic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 8, 7630–7638 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govorov A. O., Zhang H. & Gun'ko Y. K. Theory of photoinjection of hot plasmonic carriers from metal nanostructures into semiconductors and surface molecules. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 16616–16631 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. M. Electronic Structrure: Basic Theory and Practial Methods Cambridge Univ. Press (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hybertsen M. S. & Louie S. G. Electron correlation in semiconductors and insulators: Band gaps and quasiparticle energies. Phys. Rev. B 34, 5390 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noffsinger J. et al. EPW: A program for calculating the electron–phonon coupling using maximally localized Wannier functions. Comp. Phys. Commun. 181, 2140–2148 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi M., Vigil-Fowler D., Lischner J., Neaton J. B. & Louie S. G. Ab initio study of hot carriers in the first picosecond after sunlight absorption in Silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 257402 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahan G. D. Many-Particle Physics Springer (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Schrieffer J. R. Theory of superconductivity, Advanced book classics Perseus Books (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Giustino F., Cohen M. L. & Louie S. G. Electron–phonon interaction using Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 76, 165108 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko A., Polini M. & Novoselov K. Graphene plasmonics. Nat. Photonics 6, 749–758 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pines D. & Schrieffer J. R. Approach to equilibrium of electrons, plasmons, and phonons in quantum and classical plasmas. Phys. Rev. 125, 804 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Loudon R. The Quantum Theory of Light Oxford Univ. Press (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Nkoma J., Loudon R. & Tilley D. Elementary properties of surface polaritons. J. Phys. C 7, 3547–3559 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Elson J. M. & Ritchie R. H. Photon interactions at a rough metal surface. Phys. Rev. B 4, 4129–4138 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Raether H. Surface Plasmons on Smooth and Rough Surfaces and on Gratings Springer (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Zayats A. V., Smolyaninov I. I. & Maradudin A. A. Nano-optics of surface plasmon polaritons. Phys. Rep. 408, 131–314 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B. R., Ehrenreich H. & Philipp H. R. Optical properties of noble metals. Phys. Rev. 138, A494–A507 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. B. & Christy R.-W. Optical constants of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B 6, 4370–4379 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- Paggel J., Luh D.-A., Miller T. & Chiang T.-C. Electronic-structure dependence of the electron–phonon interaction in Ag. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 186803 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopitzki K. & Herzog P. Einführung in die Festkörperphysik Springer (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft N. W. & Mermin N. D. Solid State Physics Saunders College (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa R., Wang S. & Lengeler B. Energy dependence of the Fermi surface and thermoelectric power of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B 18, 1533 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rey M., Alducin M., Juaristi J. & de Andres P. Diffusion of hydrogen in Pd assisted by inelastic ballistic hot electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 115902 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitarke J., Silkin V., Chulkov E. & Echenique P. Theory of surface plasmons and surface-plasmon polaritons. Rep. Prog. Phys. 70, 1 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P. & Zunger A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Giannozzi P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troullier N. & Martins J. L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 43, 1993 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslippe J. et al. BerkeleyGW: A massively parallel computer package for the calculation of the quasiparticle and optical properties of materials and nanostructures. Comp. Phys. Commun. 183, 1269–1289 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Baroni S., de Gironcoli S., Dal Corso A. & Giannozzi P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Marzari N. & Vanderbilt D. Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Bassani F. & Parravicini G. P. Electronic States and Optical Transitions in Solids Pergamon (1975). [Google Scholar]