Abstract

Moisture-responsive materials are gaining greater interest for their potentially wide applications and the readily access to moisture. In this study, we show the fabrication of moisture-responsive, self-standing films using sustainable cellulose as starting material. Cellulose was modified by stearoyl moieties at first, leading to cellulose stearoyl esters (CSEs) with diverse degrees of substitution (DSs). The films of CSE with a low DS of 0.3 (CSE0.3) exhibited moisture-responsive properties, while CSEs with higher DSs of 1.3 or 3 (CSE1.3 and CSE3) not. The CSE0.3 films could reversibly fold and unfold as rhythmical bending motions within a local moisture gradient due to the ab- and desorption of water molecules at the film surface. By spray-coating CSE3 nanoparticles (NPs) onto CSE0.3 films, moisture-responsive films with non-wetting surface were obtained, which can perform quick reversible bending movements and continuous shape transition on water. Furthermore, bilayer films containing one layer of CSE0.3 at one side and one layer of CSE3 at the other side exhibited combined responsiveness to moisture and temperature. By varying the thickness of CSE0.3 films, the minimal bending extent can be adjusted due to altered mechanical resistances, which allows a bending movement preferentially beginning with the thinner side.

Moisture-responsive behaviors are widely spread in nature, such as moisture-responsive events of plants and fungi during the dispersion of seeds and spores1,2, the opening of pine cones, twisting and bending of wheat awns (Triticum turgidum)3,4,5,6. During the alteration of the environmental moisture content, i.e. relative humidity, a particular part of the biological systems reversibly absorbs or releases the moisture. During this process, a mechanical deformation takes place, with the goal to perform a desired function such as directed complex motions1,4. Inspired by nature, moisture-responsive materials have awoken great interest. Due to the environmentally friendly character of water vapor and its easy accessibility, moisture-responsive materials are promising candidates for broad applications, e.g. sensors7,8, actuators9,10,11 or construction of soft robots12,13.

Although water- or moisture-responsive polymers are readily to be prepared, the polymers that can be transformed into functional, fast responsive materials beyond the molecular level are still limited. Films from polyurethane or cross-linked chitosan with an epoxy compound have shown moisture-responsive properties14,15,16. Water-responsive hydrogels based on polyglycidyl methacrylate have been used for the construction of responsive actuator17. Most recently, the composite films consisting of polypyrrole and polyol-borate were shown to be fast moisture-responsive and of particular interest for generation of piezoelectric energy11.

In addition, there is ever greater interest of using sustainable compounds, e.g. using cellulose, for the construction of functional materials in recent years18,19,20. Cellulose, consisting of β–1,4–linked anhydroglucose units (AGUs), represents the most abundant material on earth. Cellulose esters and ethers have found many applications in our daily life, such as textiles, food additives and packaging materials20,21. Moisture-responsive, shape-memory composites containing cellulose nanowhiskers or microcrystalline cellulose have been reported recently22,23,24,25,26,27. In addition to crystalline cellulose as reinforcing component, a synthetic polymer, such as ethylene oxide-epichlorohydrin copolymer (1:1), poly(D, L-lactide), polyurethane or poly(glycerol sebacate urethane), was generally required as the responsive components in these composites15,22,23,24,25,26,27. In contrast, still no successful fabrication of moisture-responsive devices from pristine cellulose-derived materials without any other additives has been reported, such as self-standing films. This fact on the one hand limits the application of cellulose and on the other hand addresses new challenges for the development of cellulose-based compounds, which requires the precise control on polar and non-polar moieties.

In this report, we show the first moisture-responsive, self-standing and transparent films using derivatives of sustainable cellulose, cellulose stearoyl esters (CSEs). Thin films of CSE with a low degree of substitution (DS) of 0.3 (CSE0.3) showed a fast and reversible response to moisture. In contrast, thin films from CSE with higher DS of 1.3 (CSE1.3) and 3 (CSE3) did not show significant moisture-response. Moreover, CSE0.3 films were converted into non-wetting films after spray-coating with nanoparticles (NPs) from CSE3, which allowed CSE0.3 films to continuously move on water surface. By combining the film of CSE0.3 and CSE3, bilayer films containing a hydrophilic and a hydrophobic layer at each side were further prepared, which are responsive to both temperature and moisture.

Results

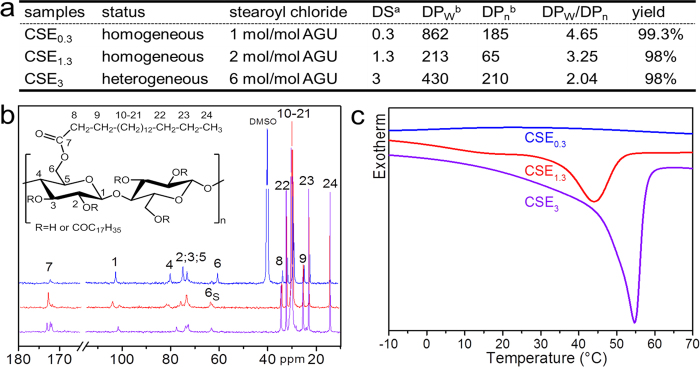

Synthesis of cellulose stearoyl esters

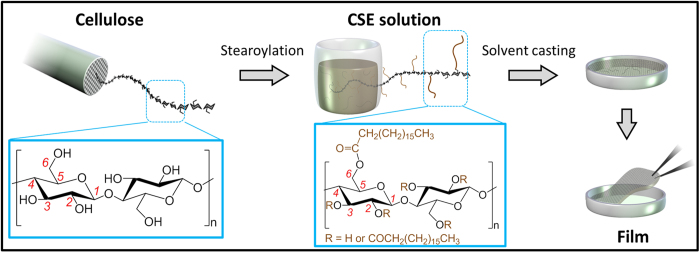

The primary concept for the fabrication of stimuli-responsive films using cellulose stearoyl esters (CSEs) is shown in Fig. 1. Cellulose stearoyl esters (CSEs) with different degrees of substitution (DSs) of 0.3, 1.3 and 3 were synthesized via two distinct synthesis routes, either heterogeneously with cellulose suspended in pyridine or homogeneously with cellulose dissolved in DMAc/LiCl before the chemical modification (Scheme S1). The DS of CSE could be adjusted by varying the amount of acid chloride for the esterification (Fig. 2a)28,29. CSE3 with the maximal DS of 3 was achieved with 6 mol stearoyl chloride/mol AGUs, while cellulose underwent a progress from a heterogeneous to a homogeneous condition during the reaction. CSEs with lower DS of 1.3 and 0.3 were synthesized with cellulose dissolved in DMAc/LiCl before the reaction using 2 and 1 mol stearoyl chloride/mol AGU, respectively. Although the synthesis of CSE1.3 in DMAc/LiCl begins with dissolved cellulose, it ends up heterogeneously due to the poor solubility of obtained CSE1.3 in DMAc/LiCl. FTIR spectra of synthesized CSEs showed typical signals attributed to aliphatic chains and ester bonds (Figure S1). All signals attributed to stearoyl groups exhibit increasing intensities with higher DS, while the intensity of the FTIR band attributed to stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups decreases and the peak maximum is shifting to higher wavenumbers.

Figure 1. Schematic representation for the synthesis of cellulose stearoyl esters (CSEs) from cellulose and the fabrication of films by solvent-casting solutions of CSEs.

Figure 2. Cellulose stearoyl esters (CSEs).

(a) Synthesis and characterization of CSEs. aDSs were determined via elemental analysis. bWeight- and number-averaged degrees of polymerization (DPW and DPn). The DP of CSE0.3 was measured due to its solubility in DMF/LiCl solution by using a RI detector. (b) 3C NMR spectra (180–10 ppm) of CSEs with different DSs recorded in corresponding solvents at 50 °C: CSE0.3 in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 (blue); CSE1.3 in pyridine-d5 (red) and CSE3 in benzene-d6 (purple). The inset shows the schematic chemical structure of CSE. (c) Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves (2nd cycle) of CSE0.3, CSE1.3 and CSE3.

In comparison to widely used 1H NMR and solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectroscopy, liquid-state 13C NMR and 2D NMR spectra of long chain fatty acid esters of cellulose with low and intermediate DS are scarcely performed in contrast to cellulose esters with short alkane chains (<6 carbons)30,31,32,33,34. For the liquid-state NMR analysis of CSEs as well as the solvent-casting process, suitable solvents were chosen based on their solubility parameters (Table S1-S3): benzene-d6 for CSE3, pyridine-d5 for CSE1.3 and DMSO–d6 for CSE0.3.

By using 2D 1H,1H-correlation spectroscopy (COSY), heteronuclear single-quantum correlation (HSQC) and heteronuclear multi-bond correlation spectroscopy (HMBC), the exact assignment of the signals was performed (Figure S2–S4). Representative 13C NMR spectra of CSEs with different DSs are shown in Fig. 2b. The signals around ~173 ppm are attributed to the carbon of C = O groups. The signals between 60 and 10 ppm are ascribed to the carbons of aliphatic chains, while the carbons of AGUs of cellulose represent signals between 110 and 60 ppm (Table S4)31,35,36. The shift of C6-signal from 60.2 to ~63 ppm indicates the esterification of primary hydroxyl groups. The splitting of C1-signal with the emergence of a new signal at 101.5 ppm is caused by the derivatization of hydroxyl groups on C2-position. It is visible that the CSE0.3 exhibits only a partial shift of the C6-signal, while the C6-signals of CSE1.3 and CSE3 are totally shifted from 60 to ~63 ppm. Thus, the primary hydroxyl groups in CSE0.3 were only partially modified by stearoyl groups, while those of CSE1.3 and CSE3 were totally esterified. Moreover, the C1-signal within the NMR spectrum of CSE0.3 was not shifted, implying no modification of hydroxyl groups at C2–position. In comparison, CSE1.3 and CSE3 exhibited partial and total derivatization of hydroxyl groups at C2-positions, according to the splitting of C1-signal and total shift of C1-signal, respectively30. Furthermore, in HMBC spectrum of CSE0.3, the 2J and 3J couplings of the ester carbon at C6-position (C = O@6) with the hydrogen atoms at C8 and C9 in aliphatic chains are notable (Figure S4a).

The presence of diverse contents of stearoyl moieties is also represented by DSC measurements (Fig. 2c). No significant crystalline character is observable for CSE0.3 due to very low content of stearoyl groups. In contrast, CSE3 shows a strong DSC signal with the maximum at 55 °C, indicating the presence of crystalline structure that was constructed by stearoyl groups. CSE1.3 with a DS of 1.3 shows a glass-transition temperature at ~10 °C and a broad peak with a maximum at 44 °C. The shape of the peaks ascribed to crystalline character is typical for partially crystalline polymers. As reported before, highly substituted cellulose long chain esters with aliphatic chain lengths of more than 12 are able to form ordered regions via side chains37,38. Hence, the aliphatic chains at cellulose backbones should have partially crystallized. The extent of the crystalline regions increases with higher content of stearoyl groups, based on the shifted peak maximum to higher temperature and stronger peak intensity.

Fabrication and characterization of films

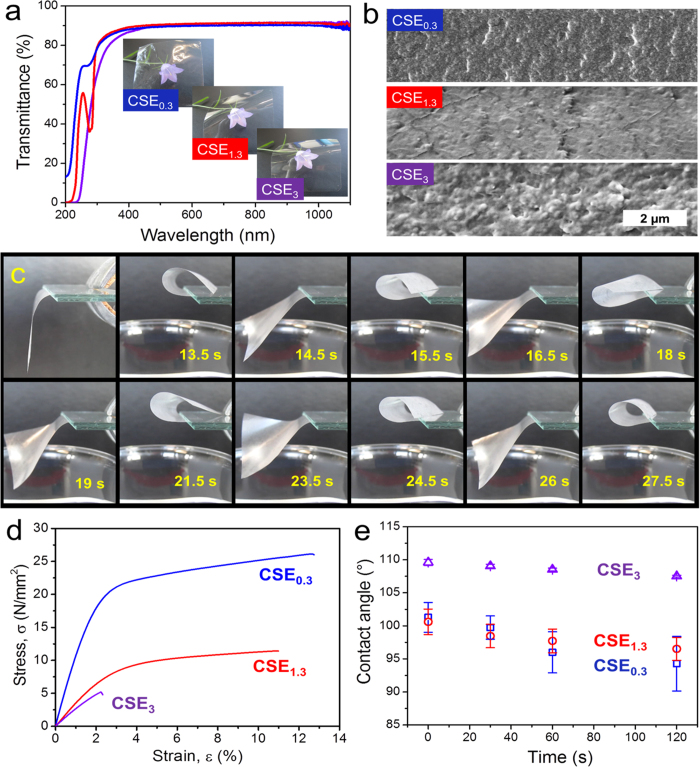

After solvent-casting solutions of CSEs, films with a thickness of around 20 μm are all highly transparent (Figs 1,3a & S5). The transmittance for visible light within the wavelength range of 400–800 nm is constantly around 90%. Moreover, the films contain homogeneous structure as shown by SEM images of their cross sections (Fig. 3b). In comparison, the membrane of regenerated cellulose is also highly transparent, but shows a layered structure (Figure S6). The homogeneous structure of CSEs films is ascribed to the drying process from their solutions.

Figure 3. Characteristics of CSE0.3, CSE1.3 and CSE3 films with a thickness of 21.2 ± 1.6, 20.6 ± 1.6 and 20.3 ± 2.2 μm, respectively.

(a) UV-Vis transmittance spectra and representative photographs of CSEs films (40 × 40 mm2) covering a flower for the visualization of their transparency. (b) SEM images of the cross sections of CSEs films with scale bar of 2 μm. (c) Snapshots of a bending CSE0.3 film (40 × 40 mm2) with a thickness of 21.2 ± 1.6 μm. One side of the film is fixed between two glass slides. Movie SM1 was recorded at 35 ± 2% RH and 22 ± 3 °C. The moisture-responsive movements immediately took place after placing warm water of 37 °C under the film. (d) Representative stress-strain curves recorded during tensile strength tests on the CSEs films at 23 ± 1 °C and 50 ± 2% RH. (e) Static water contact angles on CSEs films at 23 ± 1 °C and 50 ± 2% RH.

Among the CSEs films, only CSE0.3 films showed the most pronounced moisture-responsive motions. CSE0.3 films bend when they are exposed to water vapor under ambient conditions of 35 ± 2% relative humidity (RH) and 22 ± 3 °C (Fig. 3c, Movie SM1). In comparison, the films from CSE1.3 and CSE3 did not show significant response when exposed to water vapor under the same conditions (Figure S7). After contacting with water vapor, the CSE0.3 strip began to bend and fold up within 1–2 s (Fig. 3c). After reaching the maximal bending extent, the strip bent down within 1–2 s (Movie SM1). Once it has contact with water vapor, the CSE0.3 strip could curl up again and this folding-unfolding process repeat rhythmically with the same frequency. In contrast, a cellulose membrane with a comparable thickness (24.3 ± 1.2 μm) needed much longer time (~10 s) to fully bend (Movie SM2). No responsive bending of CSE0.3 films were observed by approaching them to silicone oil of 37 °C (Figure S8). Thus, a heating effect, i.e. the temperature (37 °C), can be excluded as trigger for the movements of CSE0.3 films above the warm water surface. The fast movements in response to moisture allow such films to be promising candidates for energy harvesting, such as generator for piezoelectricity11,39,40. Moreover, they can be used as substrates for the embedded sensors for moisture or even as prototypes for the development of artificial skin41,42. Thus, it is essential to understand the properties of films based on esterified celluloses and to find out the mechanism for the rapid responsiveness.

The mechanical properties of CSEs films were further studied by measuring their tensile strengths (Fig. 3d). CSE0.3 films of ~20 μm showed the highest tensile strength and elastic modulus among the CSEs films. With an increasing DS from 0.3 through 1.3 to 3, steadily lower tensile strengths and elastic modulus were determined for CSE1.3 and CSE3 (Fig. 3d & Table S5). Moreover, the CSE0.3 film exhibits a fracture strain, i.e. strain at break, of 12.7% ± 1.7%, in comparison to 10.7% ± 2.3% and 2.5% ± 1% of CSE1.3 and CSE3 films, respectively. Thus, CSE0.3 film is the strongest and at the same time the most flexible one among all three kinds of CSEs films. Nevertheless, the tensile strength and elastic modulus of CSE0.3 films are much lower than those of cellulose membranes (Table S5 & Figure S9). However, the cellulose membrane is very stiff, so that a deformation is difficult (Movie SM2). Thus, a low amount of stearoyl groups at cellulose backbone dedicate themselves as plasticizer within CSE0.3 films43. Furthermore, all three CSEs films exhibited hydrophobic surfaces with static water contact angles of >90° (Fig. 3e), which are ascribed to enhanced non-polarity due to the presence of stearoyl groups.

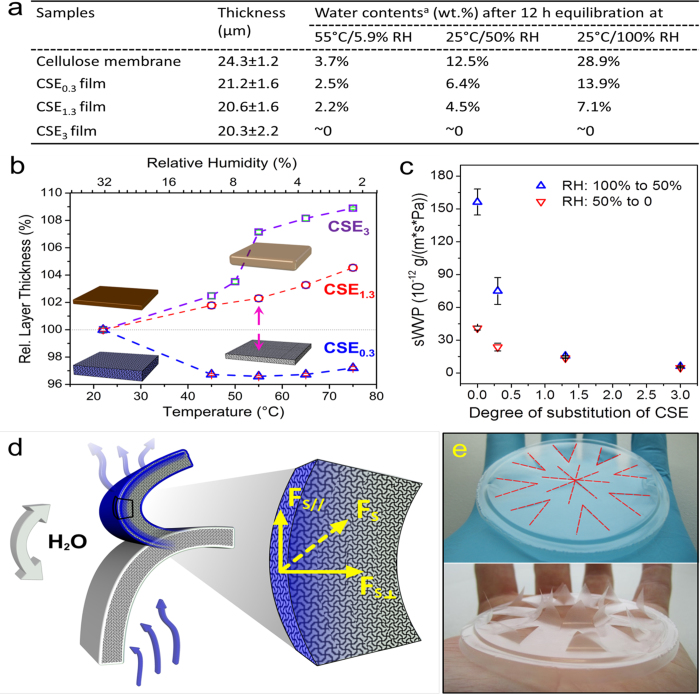

In addition to the mechanical properties, interactions between CSEs films and water are further analyzed regarding the moisture-responsiveness of CSE0.3 films. The capability of binding water at diverse RH was evaluated by measuring the amount of absorbed water by CSEs films (Fig. 4a & S10). Under a certain RH and temperature, CSE0.3 film can absorb more water than films of CSE1.3, but less than cellulose membrane. For instance, after the equilibration in the environments with a RH of 100% at 25 °C, it is visible that CSE0.3 films absorbed up to about 14 wt.% water. In comparison, CSE1.3 films only contained 7.1 wt.%, while CSE3 did not show significant absorption of water44. At a lower humidity of 50% RH at 25 °C, CSE0.3 film contains 6.4 wt.% water, and even less water (2.4 wt.%) is found at 5.9% RH. The feasibility of binding water is primarily due to the presence of numerous of hydroxyl groups within CSE0.3 and CSE1.3 films. Thus, at a low humidity, e.g. ambient humidity of 35%, CSE0.3 films are still capable of binding more water, if they are exposed to water vapor with higher contents of moisture.

Figure 4.

(a) The water contents in CSEs films after the equilibration under different temperatures and RH. A membrane from regenerated cellulose with the thickness of 24.3 ± 1.2 μm was analyzed as reference. a Standard deviations for all water contents are <5%. (b) Temperature- and RH-dependent alteration of thicknesses of CSEs films measured by ellipsometry. The short green, black and magenta lines are error bars. The magenta arrows indicate the thickness change from the initial film thickness, which was normalized as 100%. (c) Static water vapor permeability (sWVP) of a cellulose membrane (with a DS of 0) and CSEs films. The difference of water vapor partial pressure between the two sides of the membranes and films was 1.4 kPa. The short black lines are error bars. (d) Schematic representation for the moisture-responsive bending of CSE0.3 film, which is triggered by water absorption and desorption. The blue layer indicates the surface layer of the film with absorbed water. The white layers represent the surface layer of the film without water. (e) Photo images of a moisture-responsive CSE0.3 film with a thickness of 19.9 ± 1.2 μm and pre-cut triangle openings by placing the film on a hand with and without a rubber glove. The pre-cut positions are marked by red dotted lines.

After the absorption of water molecules, CSE0.3 films are swollen, which is represented by the increase of film thicknesses as detected by ellipsometry (Fig. 4b). By decreasing the temperature from 55 °C to 22 °C and thus increasing the RH from 5.9% to 35%, a thickness increase of 3.5% was measured for CSE0.3 films. This thickness increase is primarily caused by water absorption during the rising of RH. Moreover, the thickness alteration is reversible, indicating that the water molecules in CSE0.3 films are releasable and CSE0.3 films can rebind water molecules. In comparison, the thickness of CSE1.3 and CSE3 films decreased during the same treatment for 2% and 7.1%, respectively (Fig. 4b). Because the films for ellipsometry analysis exhibited a relative large surface area (20 × 20 mm2) and a much lower thickness (~180 nm), the decrease of the thickness represents the shrinkage of the film volume. The reduction of the volumes of CSE1.3 and CSE3 films at 22 °C is ascribed to the presence of a partially crystalline structure and thus a more compact structure. At the temperature of higher than 55 °C (Fig. 2c), a larger volume is resulted due to the formation of disordered structures within CSE1.3 and CSE3 films. Hence, CSE1.3 and CSE3 films show temperature-responsive property, which is based on the construction and destruction of crystalline regions consisting of stearoyl moieties. This temperature-responsive behavior can be represented by reversible changes of film volumes.

The feasibility of CSEs films to absorb and desorb water was further represented by their static water vapor permeability (sWVP). As shown in Fig. 4c, CSE0.3 films are more permeable for water vapor than CSE1.3 and CSE3 films. Under equal conditions, the sWVP is strongly affected by the swelling ability of a film. CSE0.3 films exhibit a significantly higher sWVP than CSE1.3 and CSE3 films, because CSE0.3 films are more swellable due to the presence of more hydroxyl groups. Moreover, sWVP of CSE0.3 films is affected by the moisture in the environment. Under higher humidity, CSE0.3 films contain more water and their sWVP is higher, as shown by the water permeation process from 100% RH to 50% RH in comparison to the same process from 50% RH to ~0% RH. Thus, CSE0.3 films can not only absorb and desorb water molecules, but also are permeable to water molecules. The content of water within CSE0.3 films is adjusted by the humidity of the environment. When a CSE0.3 film is exposed to water vapor, it absorbs water molecules at the surface facing the water vapor. The film expands vertically and horizontally, which causes a vertical and a horizontal swelling force. As the result, a net folding force, the swelling force FS, is generated. It applies on the film and causes the film to bend (Fig. 4d).

During the film deformation, the elastic energy is increased at the cost of the mechanical energy caused by the swelling force. For a thin film, the bending energy can be estimated as Bk2L2,45, where k is the curvature, L is the characteristic length of the bending (in the order of the maximum bending radii) and B = Eh3/[12×(1 − v2)] is the bending stiffness with E: the elastic modulus, h: the thickness of the film and v: the Poisson’s ratio (~0.3 for microcrystalline cellulose)46. The mechanical energy scales as FSL. By balancing these two terms, FS ~ Bk2L is obtained. Considering the characteristic parameters of CSE0.3 films, E = 1118 MPa, h = 21.2 μm, L = 4.6 mm and k ~ 1/L, a folding force of FS ~ 16 μN is obtained, which is comparable to the force to bend stiff cantilevers47.

After folding up, the swollen surface of the CSE0.3 film is now in an environment with lower RH, i.e. lower moisture content. Therefore, water molecules quickly evaporate, leading to the release of the bending force. Then, the CSE0.3 film unfolds and falls down under the gravity to its initial state (Movie SM1). By absorbing and desorbing water, the CSE0.3 film can reversibly fold up and fall down, i.e., the CSE0.3 film shows a moisture-responsive and shape-memory property. The moisture-responsiveness of the CSE0.3 film is so sensitive that even human skin can induce responsive movements, as shown by the opening of the pre-cut triangles within the film (Fig. 4e).

Moisture-responsive CSE0.3 films with modified properties

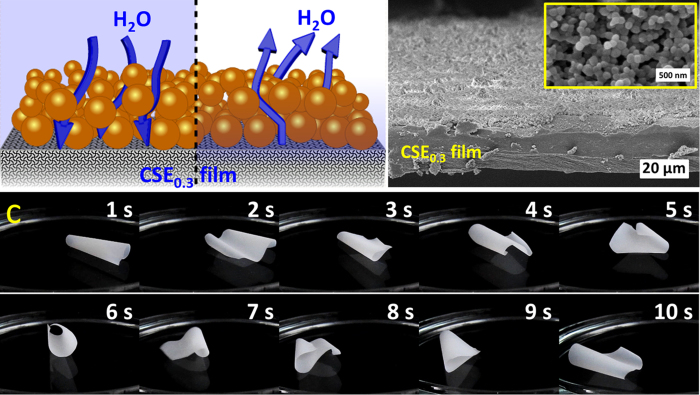

Moisture-responsive CSE0.3 films can be further modified into non-wetting films or multi-responsive films by combining NPs or films of CSE3. Although the film from CSE3 did not show moisture-responsive motions because of its high amount of non-polar stearoyl groups, CSE3 can be transformed into NPs via nanoprecipitation. CSE3 NPs can be used for the fabrication of superhydrophobic surfaces, if they are spray-coated onto diverse substrates44. Due to the fast moisture-responsive movement of CSE0.3 film, it is of great interest to fabricate non-wetting CSE0.3 films for the applications even in the presence of high amounts of liquid water. To achieve this goal, CSE0.3 films were covered with CSE3 NPs through spray-coating, leading to a non-wetting NP layer attached at the film surface (Fig. 5a,b). The NPs from CSE3 exhibit an average diameter of 98.8 ± 30 nm based on the diameters of 100 single NPs. The sprayed layer has an average thickness of 2.3 ± 1.4 μm based on SEM measurements and the density of NPs was measured to be ~0.34 mg/cm2 film. As-prepared CSE0.3 films covered with NPs showed continuous bending movements on water surface at 22 °C (Fig. 5c & Movie SM3). Thus, the layer of CSE3 NPs is non-wetting and is permeable for water vapor, which reaches the surface of CSE0.3 films and induces the reversible moisture-responsive movement of CSE0.3 films (Fig. 5c). Moreover, during the bending movements on water, the shape deformation and transition of CSE0.3 films were totally reversible.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic representation for the CSE0.3 film covered with CSE3 NPs. Under conditions with high moisture contents (left side with blue background), water vapor can penetrate through the NPs layer and reach CSE0.3 film (represented by blue arrows). Under conditions with low moisture contents (right side), water vapor can be emitted again (represented by blue arrows). (b) A SEM image of the side profile of a CSE0.3 film with CSE3 NPs on the surface. Scale bar: 20 μm. The inset shows the SEM image of the CSE3 NPs with the scale bar of 500 nm. (c) Snapshots of CSE0.3 films with homogeneous thickness of 21.2 ± 1.6 μm coated with CSE3 NPs floating and moving on water surface at 22 °C in the air (Movie SM3).

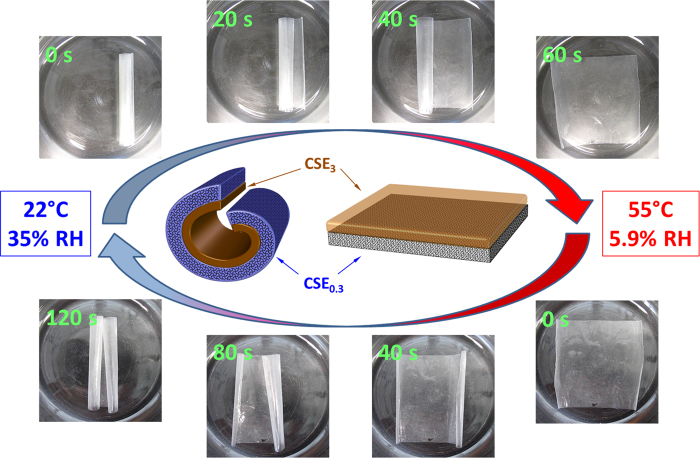

Moreover, the film of CSE3 is sensitive to temperature and undergoes a temperature-induced volume expansion (Fig. 4b). By combining a CSE3 film of ~20 μm with a moisture-responsive CSE0.3 film of ~20 μm, bilayer films were obtained which show a hydrophilic surface at one side and a hydrophobic surface at the other side (Fig. 6). These bilayer films combine the responsive properties of both components. As shown in Fig. 6, as long as a bilayer film was kept under the conditions for its formation (55 °C and 5.9% RH), they stayed as planar films. By cooling down to 22 °C with the accompanied increase of RH to 35%, the bilayer film started to curl due to the solidification and slight contraction of CSE3 film. Finally, the bilayer film rolls up and forms a tight roll with CSE0.3 at the outside. By placing the film back to the condition of 55 °C and 5.9% RH, a reversible, defined movement can be induced and the film turned to its initial flat shape again (Fig. 6). The process could be repeated reversibly in response to the alteration of surrounding conditions, showing a shape-memory property (Movie SM4 & SM5). However, the alteration of only one parameter by changing only temperature or humidity did not cause any significant responsive movements.

Figure 6. Snapshots captured after distinct times showing the curling and uncurling of a bilayer film (40 × 40 mm2) by altering the environmental conditions.

A schematic sketch of the two main states of the bilayer film is shown in the center. On the left side: the curled bilayer film consisting of solidified CSE3 layer at 22 °C and curled CSE0.3 layer due to high moisture content (35% RH). On the right side: flat bilayer film consisting of molten CSE3 layer at 55 °C and flat CSE0.3 layer due to low moisture content (5.9% RH).

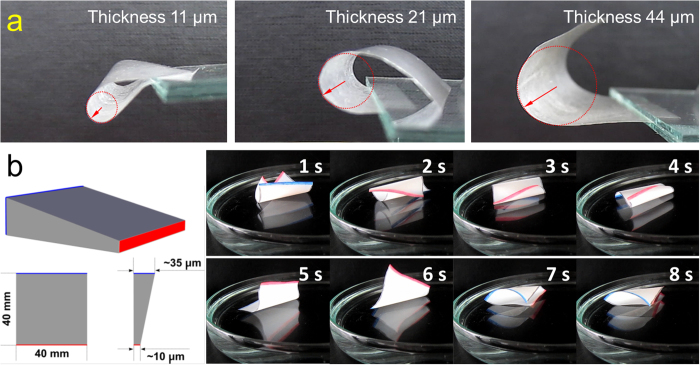

In addition to the alteration of the surface hydrophobicity of CSE0.3 films, the thicknesses of CSE0.3 films can also be modified. By increasing the film thickness, the minimal bending radius rises due to higher stiffness10,48. The radii at the maximal bending are measured to be 2.6, 4.6 and 9.6 mm for the CSE0.3 films with thicknesses of 10.9 ± 0.6, 21.2 ± 1.6 and 44.1 ± 3.5 μm, respectively (Fig. 7a & S11). The different bending extents due to the thickness provide the possibility to adjust the movement of the films by simply modifying the film thickness. A CSE0.3 film with a thickness gradient was thus fabricated and transformed into non-wetting, moisture-responsive films after spray-coating with CSE3 NPs (Fig. 7b). In comparison to the random movement of CSE0.3 films with homogeneous thickness, the thinner side of CSE0.3 films with thickness gradient bends faster than the thicker side and initiates more often the bending of the film (Movie SM6). As shown in Movie SM6, the CSE0.3 films with a thickness gradient and non–wetting surface also demonstrated the reversible shape transition process on water surface.

Figure 7.

(a) Photographs of CSE0.3 films (40 × 40 mm2) with thicknesses of 10.9 ± 0.6, 21.2 ± 1.6 and 44.1 ± 3.5 μm in the state of maximal bending. The red arrows are visualizing the corresponding bending radii. (b) CSE0.3 film with a thickness gradient from 10.3 ± 1.1 μm at the one side (marked in red) to 34.7 ± 2.2 μm at the other side (marked in blue). Right panel shows the snapshots of the CSE0.3 film (40 × 40 mm2) coated with CSE3 NPs on water surface at RT (Movie SM6).

Discussion

Inspired by naturally occurring moisture-responsive events, novel moisture-responsive materials are promising candidates for the fabrication of functional devices, such as sensors and actuators7,8,9,10,11. A particular interesting point is that the moisture is a green resource and readily available in comparison to many other stimuli, such as magnetic field and UV light with specific wave lengths49. By using a stearoyl ester of sustainable cellulose with a low degree of substitution (DS) of 0.3 (CSE0.3), transparent, self-standing and moisture-responsive films were obtained after the solvent-casting. These films exhibited rhythmical bending movements and reversible shape alterations, when they are exposed to water vapor. For instance, even the humidity of human hands can be used as stimuli and result in opening of CSE0.3 films (Fig. 4e), which can be taken as a signal. As shown above, such bending of CSE0.3 films is caused by the swelling force formed by the transient absorption of water molecules at one film surface47. Hydrogen bonding should be formed between water molecules and hydroxyl groups at cellulose backbone. After the bending from an environment with high relative humidity to an environment with low relative humidity, the swollen film surface releases the water molecules, so that it falls to its initial state due to the gravity or similar forces on both film surfaces (Figs 3c and 4d).

Other cellulose-based materials have also been reported to show moisture-responsive property, such as paper50 and films of hydroxypropylcellulose51. However, paper could not reversibly bend or move and became totally wet due to its strong capability of absorbing water50. In contrast, films of hydroxypropylcellulose exhibited reversible motions and could release water molecules in an environment of low humidity51. In comparison to films of hydroxypropylcellulose which have high DS ascribed to hydroxypropyl groups, the DS of stearoyl groups in CSE0.3 is much lower (of only 0.3), in order to achieve similar properties. In addition to various characterizations of films from CSEs showing different DSs, i.e. CSE0.3, CSE1.3 and CSE3, it is shown in the present work that the content of stearoyl groups strongly affect the properties of films derived from them.

For instances, films of CSEs with higher DSs, such as CSE1.3 and CSE3, did not show significant moisture-responsiveness. However, the films of CSE1.3 and CSE3 were responsive to the temperature. By combining the film of CSE0.3 and CSE3, bilayer films with combined thermo- and moisture-responsiveness were further fabricated. Such films can curl up into tubes as well as turn flat by changing surrounding conditions. Thus, these bilayer films not only combine the properties of two different compounds, but also endow the constructed materials new perspectives for novel applications52. For instance, stimuli-responsive microsized tubes can be fabricated from polymer films under controlled rolling conditions, which can be further used as microsized jets53,54.

By spray-coating CSE0.3 films with CSE3 NPs, CSE0.3 films with non-wetting surfaces were obtained. As-prepared CSE0.3 films show continuous bending movements on water surface and reversible shape transition. They can be used for the fabrication of moisture-responsive sensors8 or generators for piezoelectricity11. Furthermore, a thickness gradient could be generated within CSE0.3 films, so that non-symmetric bending movements can be initiated. The presence of particular structures including patterned structures within films could be used for the shape transformation of soft materials55. Moreover, controlled movements of polymeric films can be achieved, in order to use them as sensors or actuators56.

Finally, cellulose is the most abundant sustainable material on earth. It is also biocompatible, biodegradable and non-toxic20. Thus, we not only foresee a wide application range for these moisture-responsive films, but also a positive impact on the environment.

Methods

Materials

Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) with an average granule size of 50 μm and a DPn of 270 as well as stearoyl chloride (90%) were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Other chemicals are all of analytical grade and were used as received. A cellulose membrane of regenerated cellulose with a molecular weight cut-off of 3500 was received from Carl Roth GmbH & Co. (Karlsruhe, Germany).

Homogeneous synthesis of CSEs with DSs of 0.3 and 1.3 (CSE0.3 and CSE1.3)

CSEs with low and intermediate DS were prepared under homogeneous conditions28. In brief, cellulose (1 g) was dispersed in N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc) (40 ml) and the mixture was stirred at 130 °C for 30 min. Then, LiCl (3 g) was added and the system was purged with nitrogen. Under continuous stirring the suspension was allowed to cool down to room temperature (RT) overnight, leading to a clear solution. Thereafter, the temperature of the solution was raised to 60 °C, before stearic acid chloride and pyridine were added. After 3 h reaction at 60 °C, the warm reaction mixture was poured into 250 ml ethanol. The product was collected by centrifugation, purified by repeated precipitation in ethanol and dissolution in hot DMSO for CSE0.3 or tetrahydrofuran (THF) for CSE1.3, respectively.

Heterogeneous synthesis of CSE with DS of 3 (CSE3)

CSE with DS of 3 was prepared according to previous reports with some minor modifications44. Typically, cellulose (1 g) was washed with methanol and pyridine to remove traces of moisture before it was suspended in 30 ml pyridine. Then, the mixture was heated to 100 °C under stirring. Stearic acid chloride (13.83 ml, 6 mol/mol AGUs) was added in drops to the hot suspension while the system was purged with nitrogen. After 1 h stirring at 100 °C, the hot reaction mixture was poured into 200 ml ethanol. The precipitate was separated by centrifugation and purified by repeated dissolution in dichloromethane as well as precipitation in 5 volumes ethanol, before it was dried at RT.

Film formation

For the film formation, CSEs were dissolved in a proper solvent at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. The chosen solvents were toluene (CSE3), THF (CSE1.3) and DMSO (CSE0.3). The CSE solution was then pipetted into a petri dish at an amount of ~0.23 ml/cm2 and was allowed to dry. To achieve homogeneous films, the temperature was increased to 35 °C for THF, 55 °C for toluene and 90 °C for DMSO. These temperatures correspond to approximately half of the boiling point of each solvent. For the formation of films from CSE0.3 with a thickness gradient, the petri dishes were tilted at an angle of 3° during drying process. For the formation of CSE0.3/CSE3 bilayer films, a precast CSE0.3 film was covered with CSE3 solution in toluene and dried as described before.

Formation of nanoparticles (NPs) from CSE3 and spray-coating onto CSE0.3 films

CSE3 NPs were formed via nanoprecipitation by dropping the dichloromethane solution of CSE3 (10 mg/ml) into 10 volumes ethanol under ambient conditions as described before44. Then, the NPs suspensions were concentrated to about 25 mg/ml by centrifugation and spray-coated onto CSE0.3 films using an airbrush gun (Harder & Steenbeck GmbH & Co. KG, Norderstedt, Germany).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhang, K. et al. Moisture-responsive films of cellulose stearoyl esters showing reversible shape transitions. Sci. Rep. 5, 11011; doi: 10.1038/srep11011 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the Hessian excellence initiative LOEWE – research cluster SOFT CONTROL for the financial support. We thank Ms. M. Trautmann and Ms. H. Herbert for the SEC measurements. We thank Prof. M. Biesalski for the kind support. We gratefully thank Dr. H.-J. Schaffrath and Ms. L. Neumann from PMV, TU Darmstadt for the measurements on Zwick Z010.

Footnotes

Author Contributions K.Z. conceived and supervised the project. A.G. carried out the fabrication and characterization of films. M.S. and C.M.T. did the N.M.R. measurements. S. M. and M.G. did the D.S.C. and S.E.C. measurements. L.C. did the mechanical analysis on films. K.Z. and A.G. analyzed the data. K.Z. wrote the paper and all authors co-revised the paper.

References

- Fratzl P. & Barth F. G. Biomaterial systems for mechanosensing and actuation. Nature 462, 442–448 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotheim J. M. & Mahadevan L. Physical limits and design principles for plant and fungal movements. Science 308, 1308–1310 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham Y. & Elbaum R. Hygroscopic movements in Geraniaceae: the structural variations that are responsible for coiling or bending. New Phytol. 199, 584–594 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J., Vincent J. F. V. & Rocca A. M. How pine cones open. Nature 390, 668–668 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum R., Zaltzman L., Burgert I. & Fratzl P. The role of wheat awns in the seed dispersal unit. Science 316, 884–886 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung W., Kim W. & Kim H. Y. Self-burial Mechanics of Hygroscopically Responsive Awns. Integr. Comp. Biol. (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J. et al. Giant moisture responsiveness of VS2 ultrathin nanosheets for novel touchless positioning interface. Adv. Mater. 24, 1969–1974 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazoe N. & Shimizu Y. Humidity Sensors - Principles and Applications. Sens. Actuators 10, 379–398 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Jeong K.-U. et al. Three-dimensional actuators transformed from the programmed two-dimensional structures via bending, twisting and folding mechanisms. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 6824 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ji M., Jiang N., Chang J. & Sun J. Near-Infrared Light-Driven, Highly Efficient Bilayer Actuators Based on Polydopamine-Modified Reduced Graphene Oxide. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 5412–5419 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Guo L., Anderson D. G. & Langer R. Bio-inspired polymer composite actuator and generator driven by water gradients. Science 339, 186–189 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H. et al. Graphene fibers with predetermined deformation as moisture-triggered actuators and robots. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10482–10486 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y. et al. Polyelectrolyte multilayer films for building energetic walking devices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 6254–6257 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. C. et al. Rapidly self-expandable polymeric stents with a shape-memory property. Biomacromolecules 8, 2774–2780 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. M., Yang B., An L., Li C. & Chan Y. S. Water-driven programmable polyurethane shape memory polymer: Demonstration and mechanism. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 114105 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Huang W. M., Li C., Lee C. M. & Li L. On the effects of moisture in a polyurethane shape memory polymer. Smart Mater. Struct. 13, 191–195 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Sidorenko A., Krupenkin T., Taylor A., Fratzl P. & Aizenberg J. Reversible switching of hydrogel-actuated nanostructures into complex micropatterns. Science 315, 487–490 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi Y., Lucia L. A. & Rojas O. J. Cellulose nanocrystals: chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chem. Rev. 110, 3479–3500 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan F. & Ahmad S. R. Polysaccharides and their derivatives for versatile tissue engineering application. Macromol. Biosci. 13, 395–421 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm D., Heublein B., Fink H. P. & Bohn A. Cellulose: fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3358–3393 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar K. J. et al. Advances in cellulose ester performance and application. Progr. Polym. Sci. 26, 1605–1688 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Capadona J. R., Shanmuganathan K., Tyler D. J., Rowan S. J. & Weder C. Stimuli-responsive polymer nanocomposites inspired by the sea cucumber dermis. Science 319, 1370–1374 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagnon K. L., Shanmuganathan K., Weder C. & Rowan S. J. Water-Triggered Modulus Changes of Cellulose Nanofiber Nanocomposites with Hydrophobic Polymer Matrices. Macromolecules 45, 4707–4715 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. et al. Water-induced shape-memory poly(D,L-lactide)/microcrystalline cellulose composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 104, 101–108 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez J. et al. Bioinspired Mechanically Adaptive Polymer Nanocomposites with Water-Activated Shape-Memory Effect. Macromolecules 44, 6827–6835 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Frydrych M., O’Kelly K. & Chen B. Poly(glycerol sebacate urethane)-cellulose nanocomposites with water-active shape-memory effects. Biomacromolecules 15, 2663–2671 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. et al. Rapidly switchable water-sensitive shape-memory cellulose/elastomer nano-composites. Soft Matter 8, 2509 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Samaranayake G. & Glasser W. G. Cellulose derivatives with low DS. I. A novel acylation system. Carbohydr. Polym. 22, 1–7 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Vaca-Garcia C., Borredon M. E. & Gaseta A. Determination of the degree of substitution (DS) of mixed cellulose esters by elemental analysis. Cellulose 8, 225–231 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Berlioz S., Molina-Boisseau S., Nishiyama Y. & Heux L. Gas-phase surface esterification of cellulose microfibrils and whiskers. Biomacromolecules 10, 2144–2151 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan C. M., Hyatt J. A. & Lowman D. W. Two-Dimensional Nmr of Polysaccharides - Spectral Assignments of Cellulose Triesters. Macromolecules 20, 2750–2754 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli M., Sanchez F., Boisseau S. M. & Heux L. Gas-phase esterification of cellulose nanocrystal aerogels for colloidal dispersion in apolar solvents. Soft Matter 9, 11309 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli M., Ouhab D., Boisseau S. M. & Heux L. Versatile gas-phase reactions for surface to bulk esterification of cellulose microfibrils aerogels. Biomacromolecules 14, 3246–3255 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono H., Erata T. & Takai M. CP/MAS13C NMR Study of Cellulose and Cellulose Derivatives. 2. Complete Assignment of the13C Resonance for the Ring Carbons of Cellulose Triacetate Polymorphs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 7512–7518 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T., Sato Y., Shibata T., Inagaki H. & Tanahashi M. 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of Cellulose Acetate. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 22, 2363–2370 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y. & Isogai A. Preparation and characterization of cellulose β-ketoesters prepared by homogeneous reaction with alkylketene dimers: comparison with cellulose/fatty acid esters. Cellulose 14, 481–488 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Sealey J. E., Samaranayake G., Todd J. G. & Glasser W. G. Novel cellulose derivatives. IV. Preparation and thermal analysis of waxy esters of cellulose. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 34, 1613–1620 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Vaca-Garcia C., Gozzelino G., Glasser W. G. & Borredon M. E. Dynamic mechanical thermal analysis transitions of partially and fully substituted chellulose fatty esters. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 41, 281–289 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A. W. et al. Muscular thin films for building actuators and powering devices. Science 317, 1366–1370 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z. H., Cheng G., Lee S., Pradel K. C. & Wang Z. L. Harvesting water drop energy by a sequential contact-electrification and electrostatic-induction process. Adv. Mater. 26, 4690–4696 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. I. et al. Ultrathin self-powered artificial skin. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3994–3999 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Mamishev A. V., Sundara-Rajan K., Fumin Y., Yanqing D. & Zahn M. Interdigital sensors and transducers. Proc. IEEE 92, 808–845 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Crepy L., Chaveriat L., Banoub J., Martin P. & Joly N. Synthesis of cellulose fatty esters as plastics-influence of the degree of substitution and the fatty chain length on mechanical properties. ChemSusChem 2, 165–170 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler A., Chen L., Zhang K., Bonaccurso E. & Biesalski M. Superhydrophobic surfaces fabricated from nano- and microstructured cellulose stearoyl esters. Chem. Commun. 49, 4962–4964 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau L. D., Pitaevskii L. P., Kosevich A. M. & Lifshitz E. M. Theory of Elasticity, Edn. 3rd. (Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford; 1986).

- Roberts R. J., Rowe R. C. & York P. The Poisson’s ratio of microcrystalline cellulose. Int. J. Pharm. 105, 177–180 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Heim L.-O., Golovko D. S. & Bonaccurso E. Snap-in dynamics of single particles to water drops. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 031601 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- van Oosten C. L., Bastiaansen C. W. & Broer D. J. Printed artificial cilia from liquid-crystal network actuators modularly driven by light. Nat. Mater. 8, 677–682 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart M. A. et al. Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nat. Mater. 9, 101–113 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyssat E. & Mahadevan L. How wet paper curls. EPL 93, 54001 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y. et al. A cellulose liquid crystal motor: a steam engine of the second kind. Sci. Rep. 3, 1028 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoychev G., Zakharchenko S., Turcaud S., Dunlop J. W. & Ionov L. Shape-programmed folding of stimuli-responsive polymer bilayers. ACS Nano 6, 3925–3934 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cendula P., Kiravittaya S., Monch I., Schumann J. & Schmidt O. G. Directional roll-up of nanomembranes mediated by wrinkling. Nano Lett. 11, 236–240 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdanz V., Stoychev G., Ionov L., Sanchez S. & Schmidt O. G. Stimuli-Responsive Microjets with Reconfigurable Shape. Angew. Chem. 126, 2711–2715 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. L. et al. Three-dimensional shape transformations of hydrogel sheets induced by small-scale modulation of internal stresses. Nat. Commun. 4, 1586 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosono N. et al. Large-area three-dimensional molecular ordering of a polymer brush by one-step processing. Science 330, 808–811 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.