Abstract

The mouth is a mirror of health or disease, a sentinel or early warning system. The oral cavity might well be thought as a window to the body because oral manifestations accompany many systemic diseases. In many instances, oral involvement precedes the appearance of other symptoms or lesions at other locations. Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic mucocutaneous disorder of stratified squamous epithelium of uncertain etiology that affects oral and genital mucous membranes, skin, nails, and scalp. LP is estimated to affect 0.5% to 2.0% of the general population. This disease has most often been reported in middle-aged patients with 30-60 years of age and is more common in females than in males. The disease seems to be mediated by an antigen-specific mechanism, activating cytotoxic T cells, and non-specific mechanisms like mast cell degranulation and matrix metalloproteinase activation. A proper understanding of the pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis of the disease becomes important for providing the right treatment. This article discusses the prevalence, etiology, clinical features, oral manifestations, diagnosis, complications and treatment of oral LP.

Keywords: Degranulation, mucocutaneous, oral lichen planus, pathogenesis, stratified squamous

What was known?

Lichen planus is one of mucocutaneous disorder in which oral involvement precedes the appearance of other symptoms or lesions at other locations. Etiology of lichen planus as such is not known clearly, but at present it has been linked to autoimmune disorder For a general practitioner it is very important to know the important clinical features, diagnosis and treatment plan for this disease to differentiate it from other lesions. Now a days novel drug therapy and use of custom trays are of special concern for a dentist in management of oral lichen planus lesions.

Introduction

The mouth is a mirror of health or disease, a sentinel or early warning system. The oral cavity might well be thought as a window to the body because oral manifestations accompany many systemic diseases. In many instances, oral involvement precedes the appearance of other symptoms or lesions at other locations.[1] Most of the oral mucosa is derived embryologically from an invagination of the ectoderm and perhaps not surprisingly, this, like other similar orifices, may become involved in disorders that are primarily associated with the skin.

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic mucocutaneous disorder of the stratified squamous epithelium that affects oral and genital mucous membranes, skin, nails, and scalp.[2] Oral lichen planus (OLP) is the mucosal counterpart of cutaneous LP.[3] It is derived from the Greek word “leichen” means tree moss and Latin word “planus” means flat.[4]

Historical Background

The designation and description of the pathology were first presented by the English physician Erasmus Wilson in 1866.[5] He considered this to be the same disease as “lichen ruber,” previously described by Hebra[6] and characterized the disease as “an eruption of pimples remarkable for their color, their figure, their structure, their habits of isolated and aggregated development.”[7] In 1892, Kaposi reported the first clinical variant of the disease, lichen ruber pemphigoides.[8] In 1895, Wickham noted the characteristic reticulate white lines on the surface of LP papules, today recognized as Wickham striae.[9] Darier is credited with the first formal description of the histopathological changes associated with LP.[10]

Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence of LP is unknown. In 1895, Kaposi noted the disease as “rather frequent” with 25 to 30 cases presenting annually.[11] In the United States, the incidence of LP is reported to be approximately 1% of all new patients seen at health care clinics.[12] The Indian subcontinent has a particularly high incidence of disease.[13] LP is estimated to affect 0.5% to 2.0% of the general population,[14] the prevalence being ranging from 0.5% selectively in Japanese population, 1.9% in Swedish population, 2.6% in Indian population and 0.38% in Malaysia (relatively uncommon).[15] The relative risk is 3.7% in people with mixed oral habits, lowest (0.3%) in non-users of tobacco and highest (13.7%) among those who smoked and chewed tobacco.[16] This disease has most often been reported in middle-aged patients with 30-60 years of age and is more common in females than in males. OLP is also seen in children, although it is rare.[17] It affects all racial groups.[18] However, according to some literature white individuals are five and a half time more likely to develop this disease compared to other races.[19] OLP occurs more frequently than the cutaneous form and tends to be more persistent and more resistant to treatment.[20]

Etiology

Although the exact etiology of this disease is still unknown, but some factors are associated with it. These are as follows:

Genetic background

Familial cases are rare. An association has been observed with HLA-A3, A11, A26, A28, B3, B5, B7, B8, DR1, and DRW9.[21,22,23,24] In Chinese patients, an increase in HLA-DR9 and Te 22 antigens has also been noted.[25]

Dental materials

A great many materials commonly used in restoration treatments in the oral cavity have been identified as triggering elements for OLP, including silver amalgam, gold, cobalt, palladium, chromium and even non-metals such as epoxy resins (composite) and prolonged use of denture wear.[26,27,28,29]

Drugs

Oral lichenoid drug reactions may be triggered by systemic drugs including NSAIDs, beta blockers, sulfonylureas, some angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and some antimalarials, contact allergens including toothpaste flavorings, especially cinnamates.[26,30]

Infectious agents

OLP has been suggested to be related to bacteria such as a Gram-negative anaerobic bacillus and spirochetes but this has not been confirmed.[28] Some of the studies reveal the role of Helicobacter pylori (HP) in the etiology of OLP.[31,32] However, no evidence of its role has been detected in OLP in some recent studies.[33] Recently, it has been found in some literature that few periodontopathogenic microorganisms are also associated with the patients of OLP.[34] Role of candida infection is controversial in OLP. Several studies have shown an increased prevalence of candida species.[28] However, some studies reveal that there is an insignificant association between candida infection and OLP.[35,36] OLP has been found to be associated with various viral agents such as human papilloma virus (HPV),[37,38,39,40] Epstein Barr virus (EBV),[41] human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6)[39] and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[42] Epidemiological evidences from various studies worldwide strongly suggest that hepatitis C virus (HCV) may be an etiologic factor in OLP.[43,44] In OLP, HCV replication has been reported in the epithelial cells from mucosa of LP lesions by reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction or in-situ hybridization; also, HCV-specific CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes were reported in the subepithelial band. These probably suggest that HCV-specific T lymphocytes may play a role in the pathogenesis of OLP. The putative pathogenetic link between OLP and HCV still remains controversial and needs a lot of prospective and interventional studies for a better understanding.[45]

Autoimmunity

OLP may occasionally be associated with autoimmune disorders such as primary biliary cirrhosis, chronic active hepatitis, ulcerative colitis, myasthenia gravis, and thymoma.[46]

Bowel disease

Bowel diseases occasionally described concomitant with OLP include coeliac disease, ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.[47]

Food allergies

Food and some of food additives such as cinnamon aldehyde have been found to be associated with OLP.[28]

Stress

One of the factors responsible for the development of OLP is anxiety and stress. Some of the studies in literature reveal the role of the psychological stress in the etiology of OLP.[48,49,50]

Habits

Although most patients with OLP show no increased prevalence of cigarette smoking,[51] it has been suggested to be an etiological factor in some Indian communities.[52] Betel nut chewing is also more prevalent in Indian patients with OLP than in those without.[53,54,55]

Trauma

Trauma as such has not been quoted as an etiological factor in LP, although it may be the mechanism by which other etiological factors exert their effects.[28]

Diabetes and hypertension

Studies have revealed that both diabetes mellitus (DM) and high blood pressure are associated with OLP.[56,57,58,59]

(Greenspan syndrome: Triad of DM, hypertension and OLP)

Malignant neoplasms

LP has been observed on the skin and/or mucosae of patients affected by a range of different neoplasms such as with breast cancer and metastatic adenocarcinoma.[28]

Miscellaneous associations

OLP has occasionally been associated with other conditions, including psoriasis, lichen sclerosis, urolithiasis, agents used to treat gall stones, Turner's syndrome, etc.[28]

Pathogenesis

OLP is a T-cell mediated autoimmune disease in which the auto-cytotoxic CD8 + T cells trigger apoptosis of the basal cells of the oral epithelium.[60]

An early event in the disease mechanism involves keratinocyte antigen expression or unmasking of an antigen that may be a self-peptide or a heat shock protein.[61] Following this, T cells (mostly CD8+, and some CD4 + cells) migrate into the epithelium either due to random encounter of antigen during routine surveillance or a chemokine-mediated migration toward basal keratinocytes. These migrated CD8 + cells are activated directly by an antigen binding to major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-1 on keratinocyte or through activated CD4 + lymphocytes. In addition, the number of Langerhans cells in OLP lesions is increased along with upregulation of MHC-II expression; subsequent antigen presentation to CD4 + cells and interleukin (IL)-12 activates CD4 + T helper cells which activate CD8 + T cells through receptor interaction, interferon γ (INF-γ) and IL-2. The activated CD8 + T cells in turn kill the basal keratinocytes through tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, Fas-FasL-mediated or granzyme B-activated apoptosis.[62]

A Cytokine-Mediated Lymphocyte Homing Mechanism

In OLP, there is increased expression of the vascular adhesion molecules (VAM), that is, CD62E, CD54, and CD106, by the endothelial cells of the sub-epithelial vascular plexus. The infiltrating lymphocytes express reciprocal receptors (CD11a) to these VAM. Some of the cytokines that are responsible for the upregulation of the VAM are: TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-1.[63]

Nonspecific mechanisms like mast cell degranulation and MMP-1 activation further aggravate the T-cell accumulation, BM disruption by mast cell proteases and keratinocyte apoptosis.[64] The normal integrity of the BM is maintained by a living basal keratinocyte due to its secretion of collagen 4 and laminin 5 into the epithelial BM zone. In turn, keratinocytes require a BM-derived cell survival signal to prevent the onset of its apoptosis. Apoptotic keratinocytes are no longer able to perform this function, which results in disruption of the BM. Again, a non-intact BM cannot send a cell survival signal. This sets in a vicious cycle which relates to the chronic nature of the disease.[65]

The matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) are principally involved in tissue matrix protein degradation. MMP-9, which cleaves collagen 4, along with its activators is upregulated in OLP lesional T cells, resulting in increased BM disruption.[66]

RANTES (Regulated on Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed and Secreted) is a member of the CC chemokine family which plays a critical role in the recruitment of lymphocytes and mast cells in OLP. The recruited mast cell undergoes degranulation under the influence of RANTES, which releases chymase and TNF-α. These substances upregulate RANTES secretion by OLP lesional T cells.[67]

Weak expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 has been found in OLP. TGF-β1 deficiency may predispose to autoimmune lymphocytic inflammation. The balance between TGF-β1 and IFN-γ determines the level of immunological activity in OLP lesions. Local overproduction of IFN-γ by CD4 + T cells in OLP lesions downregulates the immunosuppressive effect of TGF-β1 and upregulates keratinocyte MHC class II expression and CD8 + cytotoxic T-cell activity.[68]

Clinical Features

The cutaneous lesions of LP are characterized by 5 ps: Purple, polygonal, pruritic papules and plaque.[14] Initially, LP is evident as a cutaneous and mucosal eruption, though rarely it can manifest with only oral or nail findings. LP usually begins as discrete, flat-topped papules that are 3 to 15 mm in diameter which may coalesce into larger plaques. Early in course of the disease they appear red, but soon they take on reddish purple or violaceous hue. The center of the papule may be slightly umblicated and its surface is covered by characteristic, very fine grayish white lines, called Wickham striae. The lesions can occur anywhere on the skin surface but often are located on the flexor surfaces of limbs, inner aspects of knees and thighs and trunk and also may appear on lines of trauma, reflecting the Köbner phenomenon.[7] The face frequently remains uninvolved. The primary symptom of LP is severe pruritis. The severity of pruritus varies.[16] Some patients report genital involvement with features similar to skin lesions.[69] scalp involvement (lichen planopilaris), and nail beds.[14] Rarely, there is laryngeal, esophageal and conjunctival involvement.[62]

Oral Manifestations

In the oral cavity, the disease assumes somewhat different clinical appearance than on the skin, and is characterized by lesions consisting of radiating white, gray, velvety, thread-like papules in a linear, annular and retiform arrangement forming typical lacy, reticular patches, rings and streakes. A tiny white elevated dot is present at the intersection of white lines known here as striae of Wickham as compared to Wickham striae in skin.[16] The lesions are asymptomatic, bilaterally/symmetrically anywhere in the oral cavity,[70] but most common on buccal mucosa, tongue, lips, gingiva, floor of mouth, palate and may appear weeks or months before the appearance of cutaneous lesions.

OLP has six classical clinical presentations [Figures 1-6] described in the literature:[2]

Figure 1.

Reticular type lichen planus–on the lips and mucosa of the cheek

Figure 6.

Bullous type lichen planus–lesion on upper buccal mucosa

Figure 3.

Atrophic type lichen planus–sometimes representing as desquamative gingivitis

Figure 4.

Plaque type lichen planus–lesion on tongue

Figure 5.

Papular type lichen planus–lateral border of tongue

Reticular

Erosive

Atrophic

Plaque-like

Papular

Bullous.

Reticular

It is the most common clinical form of this disease and presents with fine, asymptomatic intertwined lace-like pattern called “Wickham striae” in a bilateral symmetrical form and involves the posterior mucosa of the cheek in most cases.

Erosive

This is the most significant form of the disease because it shows symptomatic lesions often surrounded by fine radiant keratinized striae with a network appearance.[20]

Atrophic

It exhibits diffuse red lesions and it may resemble the combination of two clinical forms, such as the presence of white striae characteristic of the reticular type surrounded by an erythematous area.[2]

Plaque-like

This type shows whitish homogeneous irregularities similar to leukoplakia; it mainly involves the dorsum of the tongue and the mucosa of the cheek.[2]

Papular

This form is rarely observed and is normally followed by some other type of variant described. It presents with small white papules with fine striae in its periphery.[2]

Bullous

It is the most unusual clinical form, exhibiting blisters that increase in size and tend to rupture, leaving the surface ulcerated and painful. Nikolsky's sign may be positive.

Gingival Involvement

The gingival lesions in LP fall into one or more of the following categories [Figure 2]:[2]

Figure 2.

Erosive type lichen planus–ulcerated lesion in the buccal mucosa with erythematous borders

Keratotic lesions are usually present on the attached gingiva as small raised round white papules of pinhead size with a flattened surface.

Vesiculo-bullous lesions are other mucocutaneous disorders especially pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, or linear IgA disease.[71]

Atrophic and Erosive: Produce the desquamative gingivitis.

The triad constituted by desquamative or erosive LP involving the vulva, vagina and gingiva is termed as vulvovaginal–gingival syndrome.[72]

Diagnosis

The history, typical oral lesions and skin or nail involvement are usually sufficient to make a clinical diagnosis of OLP. However, a biopsy is the recommended procedure to differentiate it from other lesions.

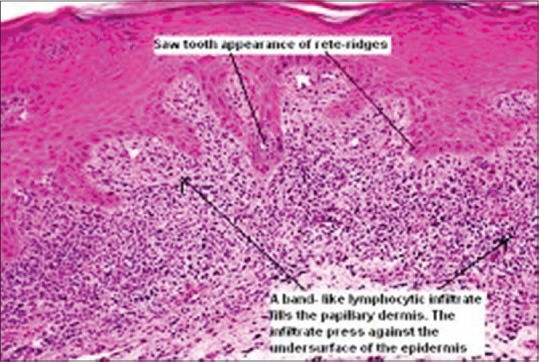

Histopathology

The classic histopathologic features of OLP include liquefactive degeneration of the basal cell accompanied by apoptosis of the keratinocytes, a dense band-like lymphocytic infiltrate [Figure 7] at the interface between the epithelium and the connective tissue, focal areas of hyperkeratinized epithelium (which give rise to the clinically apparent Wickham's striae) and occasional areas of atrophic epithelium where the rete pegs may be shortened and pointed (a characteristic known as saw tooth rete pegs). Eosinophilic colloid bodies (Civatte bodies), which represent degenerating keratinocytes, are often visible in the lower half of the surface epithelium.[14] Degeneration of the basal keratinocytes and disruption of the anchoring elements of the epithelial BM and basal keratinocytes (e.g. hemi desmosomes, filaments, fibrils) weaken the epithelial connective tissue interface. As a result, histologic clefts (Max–Joseph spaces) may form and blisters on the oral mucosa (bullous LP) may be seen at clinical examination. B cells and plasma cells are uncommon findings.[18]

Figure 7.

Histology of oral lichen planus

Direct Immunofluorescence

Immunoglobulin or complement deposits are not a consistent feature of OLP. In some instances, fibrinogen and fibrin are deposited in a linear pattern in the BM zone. Colloid bodies contain fibrin, IgM, C3, C4, and keratin. Laminin and fibronectin staining may be absent in areas of heavy fibrin deposition and colloid body formation. This finding suggests BM damage in these areas. In OLP, electron microscopy (EM) is used principally as a research tool. The ultrastructure of the colloid bodies suggests that they are apoptotic keratinocytes, and recent studies using the end labeling method revealed DNA fragmentation in these cells. EM shows breaks, branches, and duplications of the epithelial BM in OLP.[18]

Serology

There are no consistent serological changes associated with OLP but some patients do present an elevated antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer.

Hematological Investigations

Blood biochemistry and full blood examination (FBE) should also be included in the full patient workup.

Cytology

Although cytological changes may be detected in OLP, the use of exfoliative cytology is not recommended.[62] Some studies show an increased incidence of C. albicans infection in patients with OLP. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining of biopsy specimens and candidal cultures or smears may be performed.[18]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis can include cheek chewing/frictional keratosis, leukoplakia, lichenoid reactions, leukoplakia, lupus erythematous, pemphigus, mucus membrane pemphigoid, para neoplastic pemphigus, erythematous candidiasis and chronic ulcerative stomatitis, Graft vs. host disease.[3]

Malignant Potential of OLP

Malignant transformation of OLP remains a very controversial issue.[62] At least some reported cases diagnosed originally as OLP on clinical and/or histological grounds were probably epithelial dysplasia (lichenoid dysplasia) that progressed subsequently to overt squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).[73] The OLP lesions are consistently more persistent than the dermal lesions and have been reported to carry a risk of malignant transformation to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) of 1-2% (reported range of malignant transformation 0– 12.5%).[74] Erythroplastic lesions may also occur in OLP. They develop in approximately 1% of the patients and are sharp with slight reddish depressions.[2] In most cases, malignant transformation to carcinoma in situ (28.5%) and in micro invasive carcinoma (30-38%) is observed, less frequently stage I and II carcinoma. Oral cancer-correlated OLP predisposes to the development of multiple primary metachronous tumors of the oral cavity and of lymph node metastases.[75,76]

Management

The principal aims of current OLP therapy are the resolution of painful symptoms, oral mucosal lesions, the reduction of the risk of oral cancer, and the maintenance of good oral hygiene. Eliminate the local exacerbating factors as preventive measures. Up to now different therapies are described for OLP including drug therapy, surgery, psoralen with ultraviolet light A (PUVA), and laser. Use of novel drug therapy is the most common method for treatment of OLP. Different drugs have been used in the form of topical and systemic application for the treatment of OLP.[77] Drugs used in topical form are corticosteroids, immunosuppressives, retinoids, and immunomodulators. Drugs which are used systemically are thalidomide, metronidazole, griseofulvin, and hydroxychloroquine, some retinoids and corticosteroids. Small and accessible erosive lesions located on the gingiva and palate can be treated by the use of an adherent paste in the form of a custom tray, which allows for accurate control over the contact time and ensures that the entire lesional surface is exposed to the drugs.[3]

Local drug delivery can provide a more targeted and efficient drug-delivery option than systemic delivery for diseases of the oral mucosa. The main advantages of local drug delivery include (i) reduced systemic side effects, (ii) more efficient delivery as a smaller amount of drug is wasted or lost elsewhere in the body, and (iii) targeted delivery as drugs can be targeted to the diseased site more easily when delivered locally, thereby reducing side effects.[78] However, potential for novel drug delivery systems in dentistry has not yet been fully realized and further research is still needed in order to improve treatment outcomes.

Surgical excision, cryotherapy, CO2 laser, and ND:YAG laser have all been used in the treatment of OLP. In general, surgery is reserved to remove high-risk dysplastic areas.

Photo chemotherapy, a new method in which clinician uses ultraviolet A (UVA) with wavelengths ranging from the 320 to 400 nm, after the injection of psoralen is also used. Relaxation, meditation and hypnosis have positive impact on many cutaneous diseases and help to calm and rebalance the inflammatory response which can ameliorate inflammatory skin disorders.

Conclusion

OLP is a very common oral dermatitis and is one of the most frequent mucosal pathoses encountered by dental practitioners. It is imperative that the lesion is identified precisely and proper treatment be administered at the earliest. A proper understanding of the pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis of the disease becomes important for providing the right treatment.

What is new?

Lichen planus is one of mucocutaneous disorder in which oral involvement precedes the appearance of other symptoms or lesions at other locations. Etiology of lichen planus as such is not known clearly, but at present it has been linked to autoimmune disorder For a general practitioner it is very important to know the important clinical features, diagnosis and treatment plan for this disease to differentiate it from other lesions. Now a days novel drug therapy and use of custom trays are of special concern for a dentist in management of oral lichen planus lesions.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Mehrotra V, Devi P, Bhovi TV, Jyoti B. Mouth as a mirror of systemic diseases. Gomal J Med Sci. 2010;8:235–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canto AM, Müller H, Freitas RR, Santos PS. Oral lichen planus (OLP): Clinical and complementary diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:669–75. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavanya N, Jayanthi P, Rao UK, Ranganathan K. Oral lichen planus: An update on pathogenesis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:127–32. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.84474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta SB, Chaudhari ND, Gupta A, Talanikar HV. Int J Pharm Biomed Sci. 2013;4:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson E. Oralleichenplanus. J Cutan Med Dis Skin. 1869;3:117–32. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodus NL, Myers S, Kaimal S. Diagnosis and management of oral lichen planus. Northwest Dent. 2003;82:17–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma A, Białynicki-Birula R, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Lichen planus: An update and review. Cutis. 2012;90:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaposi M. Lichen ruberpemphigoides. Arch DermatolSyph (Berl) 1892;24:343–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wickham LF. Sur unsigne pathognomoniquedelichen du Wilson (lichen plan) stries et punctuations grisatres. Ann Dermatol Syph. 1895;6:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black MM. The pathogenesis of lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 1972;86:302–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaposi M. New York, NY: William Wood and Company; 1895. Pathology and Treatment of Diseases of the skin for practitioners and students. Translation of the Last German Edition under the Supervision of James C. Johnston, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1103641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh OP, Kanwar AJ. Lichen planus in India: An appraisal of 441 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:752–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1976.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards PC, Kelsch R. Oral lichen planus: Clinical presentation and management. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:494–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ismail SB, Kumar SK, Zain RB. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions; Etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:89–106. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. Shafer's textbook of oral pathology. 6th ed. Noida, India: Elsevier publications; 2009. p. 800. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boorghani M, Gholizadeh N, Zenouz AT, Vatankhah M, Mehdipour M. Oral lichen planus: Clinical features, etiology, treatment and management; A review of literature. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospect. 2010;4:3–9. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2010.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shekar C, Ganesan S. Oral lichen planus: Review. J Dent Sci Res. 2011;2(1):62–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sousa FA, Rosa LE. Oral lichen planus: Clinical and histopathological considerations. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;74:284–92. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31102-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma S, Saimbi CS, Koirala B. Erosive oral lichen planus and its management: A case series. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2008;47:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ognjenovic M, Karelovic D, Cindro VV, Tadin I. Oral lichen planus and HLA A. Coll Antropol. 1998;22:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCartan BE, Lamey PJ. Expression of CD1 and HLA-DR by Langerhans cells (LC) in oral lichenoid drug eruptions (LDE) and idiopathic oral lichen planus (LP) J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26:176–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe T, Ohishi M, Tanaka K, Sato H. Analysis of HLA antigens in Japanese with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15:529–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1986.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter K, Klouda P, Scully C, Bidwell J, Porter S. Class I and II HLA antigens in British patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:176–80. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90090-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun A, Wu YC, Wang JT, Liu BY, Chiang CP. Association of HLA-te22 antigen with anti-nuclear antibodies in Chinese patients with erosive oral lichen planus. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China B. 2000;24:63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serrano-Sánchez P, Bagán JV, Jiménez-Soriano, Sarrión G. Drug induced oral lichenoid reactions. A literature review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2010;2:e71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scully C, Carrozzo M. Oral mucosal disease: Lichen planus. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.07.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scully C, Beyli M, Ferreiro MC, Ficarra G, Gill Y, Griffiths M, et al. Update on oral lichen planus: Etiopathogenesis and management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:86–122. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Issa Y, Brunton PA, Glenny AM, Duxbury AJ. Healing of oral lichenoid lesions after replacing amalgam restorations: A systematic review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:553–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wray D, Rees SR, Gibson J, Forsyth A. The role of allergy in oral mucosal leisons. QJM. 2000;93:507–11. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.8.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moravvej H, Hoseini H, Barikbin B, Malekzadeh R, Razavi GM. Association of Helicobacter pylori with lichen planus. Indian J Dermatol. 2007;52:138–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vainio E, Huovinen S, Liutu M, Uksila J, Leino R. Peptic ulcer and Helicobacter pylori in patients with lichen planus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:427–9. doi: 10.1080/000155500300012855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hulimavu SR, Mohanty L, V Tondikulam N, Shenoy S, Jamadar S, Bhadranna A. No evidence for Helicobacter pylori in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43:576–8. doi: 10.1111/jop.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ertugrul AS, Arslan U, Dursun R, Hakki SS. Periodontopathogen profile of healthy and oral lichen planus patients with gingivitis or periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2013;5:92–7. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehdipour M, Zenouz AT, Hekmatfar S, Adibpour M, Bahramian A, Khorshidi R. Prevalence of Candida species in erosive oral lichen planus. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospect. 2010;4:14–6. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2010.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shivanandappa SG, Ali IM, Sabarigirinathan C, Mushannavar LS. Candida in oral lichen planus. J Indian Aca Oral Med Radiol. 2012;24:182–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campisi G, Giovannelli L, Aricò P, Lama A, Di Liberto C, Ammatuna P, et al. HPV DNA in clinically different variants of oral leukoplakia and lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:705–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorsky M, Epstein JB. Oral lichen planus: Malignant transformation and human papilloma virus: A review of potential clinical implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:461–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yildirim B, Senguven B, Demir C. Prevalence of herpes simplex, Epstein Barr and human papilloma viruses in oral lichen planus. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e170–4. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen S, Tsuji T, Li X, Mizugaki Y, Hayatsu Y, Shinozaki F. Detection and analysis of human papillomavirus 16 and 18 homologous DNA sequences in oral lesions. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sand LP, Jalouli J, Larsson PA, Hirsch JM. Prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma, oral lichen planus, and normal oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:586–92. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.124462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumari R, Singh N, Thappa DM. Hypertrophic lichen planus and HIV infection. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:S8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konidena A, Pavani BV. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with oral lichen planus. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14:228–31. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.84025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oliveira Alves MG, Almeida JD, Guimarães Cabral LA. Association between hepatitis C virus and oral lichen planus: HCV and oral Lichen Planus. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:132–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patil S, Khandelwal S, Rahman F, Kaswan S, Tipu S. Epidemiological relationship of oral lichen planus to hepatitis C virus in an Indian population. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2012;11:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbate G, Foscolo AM, Gallotti M, Lancella A, Mingo F. Neoplastic transformation of oral lichen: Case report and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2006;26:47–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Georgakopoulou EA, Achtari MD, Achtaris M, Foukas PG, Kotsinas A. Oral lichen planus as a preneoplastic inflammatory model. J Biomed Biotech. 2012;12:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2012/759626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eltawil M, Sediki N, Hassan H. Psychobiological aspects of patients with lichen planus. Curr Psychiatr. 2009;16:370–80. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaudhary S. Psychosocial stressors in oral lichen planus. Aus Dent J. 2004;49:192–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bajaj DR, Khoso NA, Devrajani BR, Matlani BL, Lohana P. Oral lichen planus: A clinical study. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20:154–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajendran R. Oral lichen planus. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2005;9:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorsky M, Epstein JB, Hasson-Kanfi H, Kaufman E. Smoking habits among patients diagnosed with oral lichen planus. Tob Induc Dis. 2004;2:103–8. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-2-2-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trivedy CR, Craig G, Warnakulasuriy S. The oral health consequences of chewing areca nut. Addict Biol. 2002;7:115–25. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stoopler ET, Parisi E, Sollecito TP. Betel quid–induced oral lichen planus: A case report. Cutis. 2003;71:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reichart PA, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral lichenoid contact lesions induced by areca nut and betel quid chewing: A mini review. J Investig Clin Dent. 2012;3:163–6. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1626.2012.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Torrente-Castells E, Figueiredo R, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C. Clinical features of oral lichen planus. A retrospective study of 65 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:e685–90. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albrecht M, Bánóczy J, Dinya E, Tamás G., Jr Occurrence of oral leukoplakia and lichen planus in diabetes mellitus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:364–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed I, Nasreen S, Jehangir U, Wahid Z. Frequency of oral lichen planus in patients with noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pak Assoc Derm. 2012;22:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lundström IM. Incidence of diabetes mellitus in patients with oral lichen planus. Int J Oral Surg. 1983;12:147–52. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(83)80060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eversole LR. Immunopathogenesis of oral lichen planus and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:284–94. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(97)80018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou XJ, Sugarman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Seymour GJ. Intra-epithelial CD8+T cells and basement membrane disruption in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:23–7. doi: 10.1046/j.0904-2512.2001.10063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugerman PB, Satterwhite K, Bigby M. Autocytotoxic T-cell clones in lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:449–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Regezi JA, Dekker NP, MacPhail LA, Lozada-Nur F, McCalmont TH. Vascular adhesion molecules in oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:682–90. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srinivas K, Aravinda K, Ratnakar P, Nigam N, Gupta S. Oral lichen planus-Review on etiopathogenesis. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2011;2:15–6. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.85847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lodi G, Scully C, Carozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report on an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou XJ, Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in oral lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:72–82. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.280203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao ZZ, Sugerman PB, Zhou XJ, Walsh LJ, Savage NW. Mast cell degranulation and the role of T cell RANTES in oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2001;7:246–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roopashree MR, Gondhalekar RV, Shashikanth MC, George J, Thippeswamy SH, Shukla A. Pathogenesis of oral lichen planus-a review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:729–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davarmanesh M, Dehaghani AS, Deilami Z, Monabbati A, Dastgheib L. Frequency of genital involvement in women with oral lichen planus in southern Iran. Derm Res Prac. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/365230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Radwan-Oczko M. Topical application of drugs used in treatment of oral lichen planus lesions. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2013;22:893–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Porter SR, Bain SE, Scully CM. Linear IgA disease manifesting as recalcitrant desquamative gingivitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:179–82. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pelisse M. The vulvo-vaginal-gingival syndrome: A new form of erosive lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:381–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krutchkoff DJ, Eisenberg E. Lichenoid dysplasia: A distinct histopathologic entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:308–15. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gonzalez-Moles MA, Scully C, Gil-Montoya JA. Oral lichen planus: Controversies surrounding malignant transformation. Oral Dis. 2008;14:229–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mignogna MD, Lo Muzio L, Lo Rosso L, Fedele S, Ruoppo E, Bucci E. Clinical guidelines in early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma arising in oral lichen planus: A 5- year experience. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:262–7. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mignogna MD, Lo Russo L, Fedele S, Ruoppo E, Califano L, Lo Muzio L. Clinical behaviour of malignant transforming oral lichen planus. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:838–43. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sahebjamee M, Arbabi-Kalati F. Management of oral lichen planus. Arch Iranian Med. 2005;8:252–6. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mishra SS, Maheshwari T. NU. Local drug delivery in the treatment of oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2014;5:716–21. [Google Scholar]