Abstract

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is a distressing disease encountered frequently in clinical practice. The current mainstay of therapy is the use of second-generation, non-sedating antihistamines. However, in patients who do not respond satisfactorily to these agents, a variety of other drugs are used. This article examines the available literature for frequently used agents including systemic corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, dapsone, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, H2 antagonists, methotrexate, cyclosporine A, omalizumab, autologous serum therapy, and mycophenolate mofetil, with an additional focus on publications in Indian literature.

Keywords: Alternatives, anti-inflammatory, chronic, immunosuppressive, refractory, urticaria

What was known?

Chronic Urticaria is a debilitating disease with a relapsing course.

Antihistamines form the mainstay of therapy.

In non-responders a variety of other drugs have been tried, with or without evidence to support their use.

Introduction

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is a disease affecting 0.5-1% of the population at any given time.[1] The duration of the disease is generally 1-5 years, but could be longer in more severe cases associated with features such as angioedema and autoreactivity.[1] Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) has major detrimental effects on quality of life, with sleep deprivation and psychiatric co-morbidity being frequent.

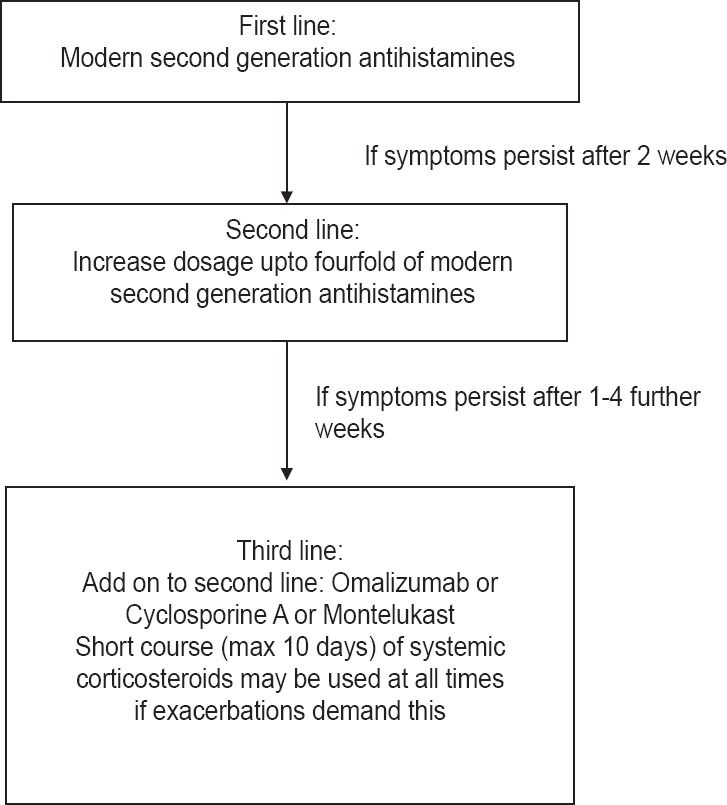

In the majority of patients, it is difficult to identify an underlying cause or inciting factor, thus preventing curative therapy. The latest EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines give the treatment algorithm to be followed in all cases of urticaria [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Recommended treatment algorithm for urticaria. Source: Zuberbier T, Asero R, Godse K, Grattan C, Maurer M et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy 2014; 69: 868–887

Non-sedating H1-antihistamines are the mainstay of symptomatic therapy, but treatment with licensed doses relieves symptoms effectively in only < 50% of patients.[1] Treatment with higher doses of H1 antihistamines (up to four-fold updosing as per current guidelines) further improves symptoms in many, but not all patients. Thus, every third or fourth patient will still remain symptomatic. These patients are classified as non-responders to antihistamines.[2]

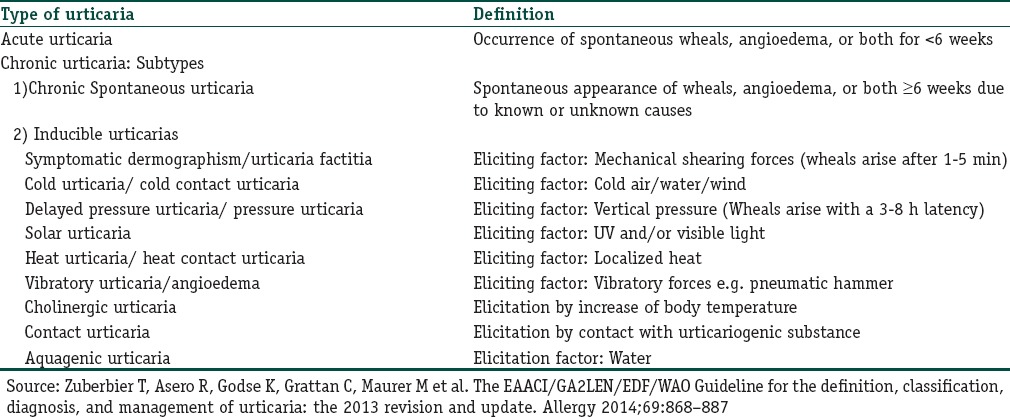

We now look at other drugs which may be used for treatment in such patients. The various types and subtypes of urticarias as referred to in the article and their definitions are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of types of urticaria

Corticosteroids

One large, retrospective study reports long-term remissions in about 50% of cases of chronic urticaria with oral prednisone given in a short course in doses of 0.3-0.5 mg/kg. The prednisone was started at a dose of 25 mg/day for 3 days followed by a rapid tapering within 10 days. The remissions achieved resulted in disease control with only antihistamines at licensed doses. On administration of a second course of prednisone, the remission rate further improved.[3]

However, systemic corticosteroids are associated with severe adverse effects on long-term treatment (glucose intolerance, hypertension, osteoporosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and weight gain). Thus, oral corticosteroids are recommended for use only as short courses in the management of urticaria.[4]

In another study from India, Oral Mini Pulse (OMP) therapy was used in a series of 10 patients of chronic urticaria. Over a period of 2 months, methyl prednisolone 16 mg tablets twice a week, on Saturday and Sunday, were given along with levocetirizine 5 mg tablet daily. A significant reduction in Mean Urticaria Activity Scores was observed in most patients, with only two patients reporting steroid-related side-effects. The OMP regimen may help to minimize side-effects of oral corticosteroid therapy.[5]

Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists (antiLTs)

Many studies have reported the efficacy of anti LTs Montelukast and Zafirlukast in Chronic Urticaria (CU). They may be especially useful in urticaria induced by food additives and/or aspirin and other NSAIDs.[6] Pacor et al. reported that the combination of antiLTs and non-sedating antihistamines gives added benefit only in urticaria elicited by a known factor (food additives, aspirin, and autoimmune urticaria). They further suggest that the combination offers no added benefit in cases of chronic idiopathic urticaria.[7] Similarly Bagenstose et al. also reported an added benefit by addition of antiLTs to cetirizine only in cases of severe autoimmune urticaria (positive autologous serum skin test).[8]

On the basis of his findings with use of antiLTs in a series 12 patients of steroid-dependent chronic urticaria and in view of their good tolerability and low cost, Asero recommends that antiLTs should be tried in all patients with unremitting, steroid-dependent chronic urticaria before more challenging therapies are considered.[9]

A few studies in the literature have reported no benefit with antiLTs, including a study from India which reports no improvement of symptoms in chronic idiopathic urticaria patients with montelukast monotherapy.[10]

However, a short trial with these agents may be recommended in all patients with refractory urticaria, before considering other therapeutic agents. Montelukast can be used in doses of 10 mg/day.

Dapsone (DDS)

Evidence for use of Dapsone in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) was first presented by I Boehm et al. in a case study published in 1999. A patient who was unresponsive to antihistamines and steroids showed remission with low-dose dapsone (started with 50 mg DDS/day, tapered to 25 mg DDS/week).[11]

More recently, Engin et al., in a prospective, randomized, non-blinded trial, comparing the use of dapsone with antihistamine versus antihistamine alone, reported a persistent decrease in VAS and UAS scores along with complete remission in some cases treated with dapsone, which was statistically significant as compared to placebo.[12]

Dapsone can be used in CU in doses of 50-100 mg/day. In 2013, a double-blind placebo controlled trial (n = 22) of antihistamine-refractory chronic urticaria reported a statistically significant improvement in itch, hive, and VAS scores in patients treated with dapsone as compared to placebo.[13]

Dapsone is associated with known side effects such as methemoglobinemia, peripheral neuropathy, skin rash, hepatotoxicity, GI disturbances. Rare side effects include DRESS syndrome. Estimation of G6PD levels before initiation of therapy is recommended in all cases, especially in males, along with monitoring of hemogram and LFTs for the duration of therapy.

Sulfasalazine

A single retrospective study of 19 patients of CU treated with sulfasalazine has been published.[14] Sulfasalazine was started at a dose of 500 mg/day and increased by 500 mg weekly until doses of 2 gm/day were reached. Doses higher than 2 gm/day offered no additional benefit and were associated with more severe side effects. The reported side effects included gastrointestinal discomfort, nausea, and mild headache, as well as leukopenia and elevated liver enzyme levels.[14]

Hydroxychloroquine

A randomized, placebo controlled, double blind study demonstrated use of hydroxychloroquine in chronic urticaria in doses of 200 mg/day for a duration of at least 12 weeks. Improvement in quality of life scores was observed.[15]

Hydroxychloroquine is a very safe drug, with most common adverse effect being GI upset. The risk of retinopathy increases significantly after 5 years of use; however, baseline ophthalmologic evaluation is recommended within first year of starting therapy.

H2 receptor antagonists

A recently published systematic Cochrane review on the use of H2 receptor antagonists for urticaria states that although some of the participants in included studies reported better symptomatic relief with combinations of H1 and H2 antihistamines, as compared to H1 antihistamines alone, the level of evidence was weak and unreliable, and hence no recommendations could be made at present.[16]

Methotrexate

Methotrexate has been reported to be useful in various anecdotal reports of selected cases published in literature.[17,18] In a report from India published in 2007, 3 out 4 selected cases of recalcitrant urticaria were controllable with only cetirizine after a 2 month course of Mtx (10 mg/week) given in divided doses every weekend, along with folic acid and cetirizine.[19]

However, a very recently published randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind pilot study from India reports that Mtx 15 mg/week for 3 months did not provided any additional benefit over H1 antihistamines. The authors have recommended a larger study with longer follow-up to validate the results.[20]

Cyclosporine (CsA)

Many studies in the literature have reported the efficacy of cyclosporine in the management of CSU. A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial by Vena et al. demonstrated good improvement with CsA in patients of CSU in doses of 3-5 mg/kg/day, given over a period of 16 weeks in addition to background cetirizine therapy.[21]

A small study from India evaluating the safety and effectiveness of CsA in patients with CSU and positive ASST reported improvement in UAS as early as within 2 weeks of therapy, along with complete remission in three out of four patients and significant improvement in the remainder at the end of therapy. The patients were given daily CsA in dose of 3 mg/kg/day for a period of 12 weeks along with daily cetirizine 10 mg.[22]

A 1-year follow-up study has shown efficacy of CsA in treatment of autoimmune urticaria, even in low doses (1.5-2.5 mg/kg/day) given over 5 months.[23] The main side effects occurring with CsA are renal damage (which may be reversible on stopping medications) and hypertension. Thus, continuous BP and BUN/S. Creatinine monitoring is required during course of therapy.

Omalizumab

A recently published, phase III, randomized, double-blind study, evaluating the safety and efficacy of Omalizumab in 323 patients with antihistamine-unresponsive, moderate-to-severe chronic urticaria, demonstrated efficacy in a dose-dependent manner. Omalizumab given subcutaneously in doses of 150 mg or 300 mg, repeated every 4 weeks for a period of 12 weeks, has significant efficacy in treatment of chronic refractory urticaria. The efficacy is dose dependent. The incidence of serious side effects was low, and more side effects were noted at higher doses.[24]

A study from India using Omalizumab in patients of long-standing chronic urticaria not responding to other therapies, showed significant improvements in all patients with reductions in UAS and need for antihistamines.[25]

Omalizumab was approved by the US FDA on 21 March 2014 for use in chronic idiopathic urticaria.

Autologous serum therapy

A placebo-controlled trial by Staubach et al. in 2006 suggested that autologous serum skin test (ASST) positive chronic urticaria patients can benefit from autologous serum therapy.[26]

A multicenter, prospective, open-label trial of autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria patients from India showed its efficacy in a significant proportion of ASST-positive patients along with some ASST-negative patients as well. At least 59.7% of ASST positive and 46% ASST-negative patients showed significant improvements in signs and symptoms after nine weekly autologous serum skin injections were given. This improvement was sustained for at least 3-4 months after the last injection.[27]

However, a randomized, three arm study from Istanbul comparing autologous serum and autologous whole blood injections to placebo injections in 88 patients of chronic urticaria could not establish a statistically significant difference in efficacy between the three methods although autohemotherapy resulted in a marked decrease in disease activity and improvement in quality of life scores in CU patients.[28]

In another trial for autologous serum therapy from India, 20 ASST-positive patients were given weekly autologous serum injections (0.05 ml/kg/week) intramuscularly, and of those, 9 (45%) showed excellent response, while another 5 (25%) showed satisfactory response to the therapy.[29]

In view of its low cost and good safety profile, autologous serum therapy may be a good option in ASST-positive patients with refractory urticaria.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)

In an open label, uncontrolled trial, on nine chronic urticaria patients who did not respond satisfactorily to anti-histamines and/or oral steroids, Shahar et al. demonstrated significant efficacy with mycophenolate mofetil. MMF was given in doses of 1000 mg twice daily for 12 weeks. Along with a significant decrease in urticaria activity score, all patients were able to stop prednisone and required lower doses of anti-histamines for disease control.[30]

In another retrospective analysis of 19 patients with autoimmune and chronic idiopathic urticaria, who were treated with MMF in dose ranges from 1000 mg to 6000 mg daily in two divided doses, improvement in urticaria was observed in 89% of these patients with mean time to control being 14 weeks. The therapy was well tolerated with most commonly reported adverse effects being GI symptoms.[31]

Phototherapy

In a randomized, controlled, non-blinded trial from Turkey on use of NBUVB phototherapy in treatment of urticaria, a total of 81 urticaria patients were recruited to the study. The study group patients (n = 45) received whole body phototherapy along with levocetirizine 10 mg daily. Phototherapy was given three times a week for 20 exposures, with initial dose of 200 mJ/cm2, and about 10-20% increments at each session. The control group received only levocetirizine 10 mg per day.[32]

On comparing the groups, the mean UAS was significantly lower in the NB-UVB plus levocetirizine group (P < 0.01 at 3 months follow up). However, the reductions in VAS were similar in both groups. The results indicate that NB-UVB phototherapy combined with antihistamine was better than antihistamine alone at reducing urticaria activity. Moreover, the improvements seen during treatment were maintained 3 months after phototherapy had been stopped. Four of the 45 patients receiving phototherapy (8.8%) reported type A adverse events such as erythema, and their phototherapy protocols were accordingly modified.[32]

Warfarin

There is a single communication of 5 cases of CIU treated with warfarin reported from India. All the 5 selected patients required oral steroids for symptom control, with relapse occurring on withdrawal. All five patients had a positive Autologous Plasma Skin Test (APST) and four had a positive ASST. Warfarin was started at a dose of 1 mg, increased by 1 mg weekly, with the maximum administered dose being 5 mg. INR was monitored and maintained below 2. Warfarin was used for 2 to 5 months, and steroids could be completely withdrawn in four cases. 1 case showed no response. The authors suggest that warfarin may be considered in subjects with CIU with coexisting diseases needing long-term warfarin, like deep vein thrombosis, atrial fibrillation or recurrent pulmonary embolism.[33]

Asero et al. demonstrated involvement of the extrinsic coagulation pathway in CIU, thus providing the rationale for anticoagulant use.[34]

Immunoglobulin (IVIg)

There have been mixed reports about efficacy of IVIg in chronic urticaria. In 2007, a study of 29 patients with CU treated with low dose IVIg (0.15 g/kg/d every 4 weeks) reported significant improvement in all patients who completed treatment, with 4.5 months being the mean time to improvement.[35]

Asero in 2000 reported a series of three patients treated with IVIg, where only one initially responded to treatment, with a relapse within 3 weeks. The author suggests that most of the observed clinical effect was due to the anti-idiotype effect of IVIg rather than immunomodulatory effects.[36]

The disadvantages of IVIg are its high cost, paucity of efficacy data, and requirement for prolonged infusions. It is associated with infusion reactions and other rare adverse events such as anaphylactoid reactions and aseptic meningitis.[37]

Doxepin

The rationale behind use of doxepin in urticaria is that tricyclic antidepressants frequently show antihistamine side effects.[38]

In a double-blind cross-over study comparing doxepin (10 mg thrice a day) with diphenhydramine (25 mg three times a day), the patients of CIU on doxepin showed significantly better improvement in symptoms with lesser sedation.[39]

Ghose and Haldar published a randomized controlled trial comparing the effect of 10 mg thrice daily doxepin with pheniramine maleate 22.5 mg three times daily. The group receiving doxepin showed significantly better improvement, with lesser drowsiness, as compared to the pheniramine group. However, dryness of mouth was more common among patients taking doxepin.[40]

Topical clobetasol

While an open trial on use of potent topical steroids in chronic idiopathic urticaria did not demonstrate lasting response,[41] two other studies on use of topical clobetasol (0.05%) have reported its significant efficacy in cases of delayed pressure urticaria as compared to placebo.[42,43]

Management of chronic urticaria in special populations

Children

Recent guidelines have strongly recommended use of modern second generation H1 antihistamines as first-line therapy for urticaria in children. In children, the same first-line treatment and weight adjusted up dosing is recommended as in adults. The treatment algorithm to be followed remains the same as elaborated in Figure 1.[44]

There is one report of a single open label trial on use of cyclosporine in children with CIU. Seven children, aged 9 to 16 yrs, were given cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/day in two divided doses, with monitoring of serum cyclosporine levels, BUN, serum creatinine, and blood pressure. All the patients had cessation of symptoms after about 1-4 weeks and maximum by 8 weeks. No adverse effects were recorded in these seven patients.[45]

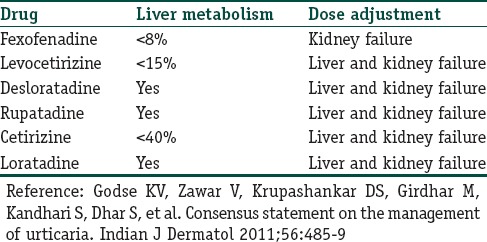

Hepatic, renal disease

Table 2 gives guidelines for choice of antihistamines in patients with hepatic and renal dysfunction.

Table 2.

Metabolism and dose adjustment of various second generation antihistamines

Pregnancy and lactation

There have been no reports of birth defects in women having used modern second-generation antihistamines during pregnancy. The latest guidelines suggest use of loratadine, cetirizine, and levocetirizine during pregnancy.[44] These are also pregnancy category B.

All antihistamines are secreted in breast milk and use of first-generation antihistamines is discouraged during lactation to avoid excessive sedation.[44]

A short course of oral corticosteroids may be considered during pregnancy in case of severe exacerbations of urticaria. Potential side effects include malformations, neonatal adrenal insufficiency, and low birth weight. Risk to benefit ratio must be assessed before administration. Although oral steroids are secreted in breast milk, they are generally considered to be safe during lactation.[4]

Omalizumab has also been classified as pregnancy category B by US FDA.[4] Drugs such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil are teratogenic and must be avoided during pregnancy.[45]

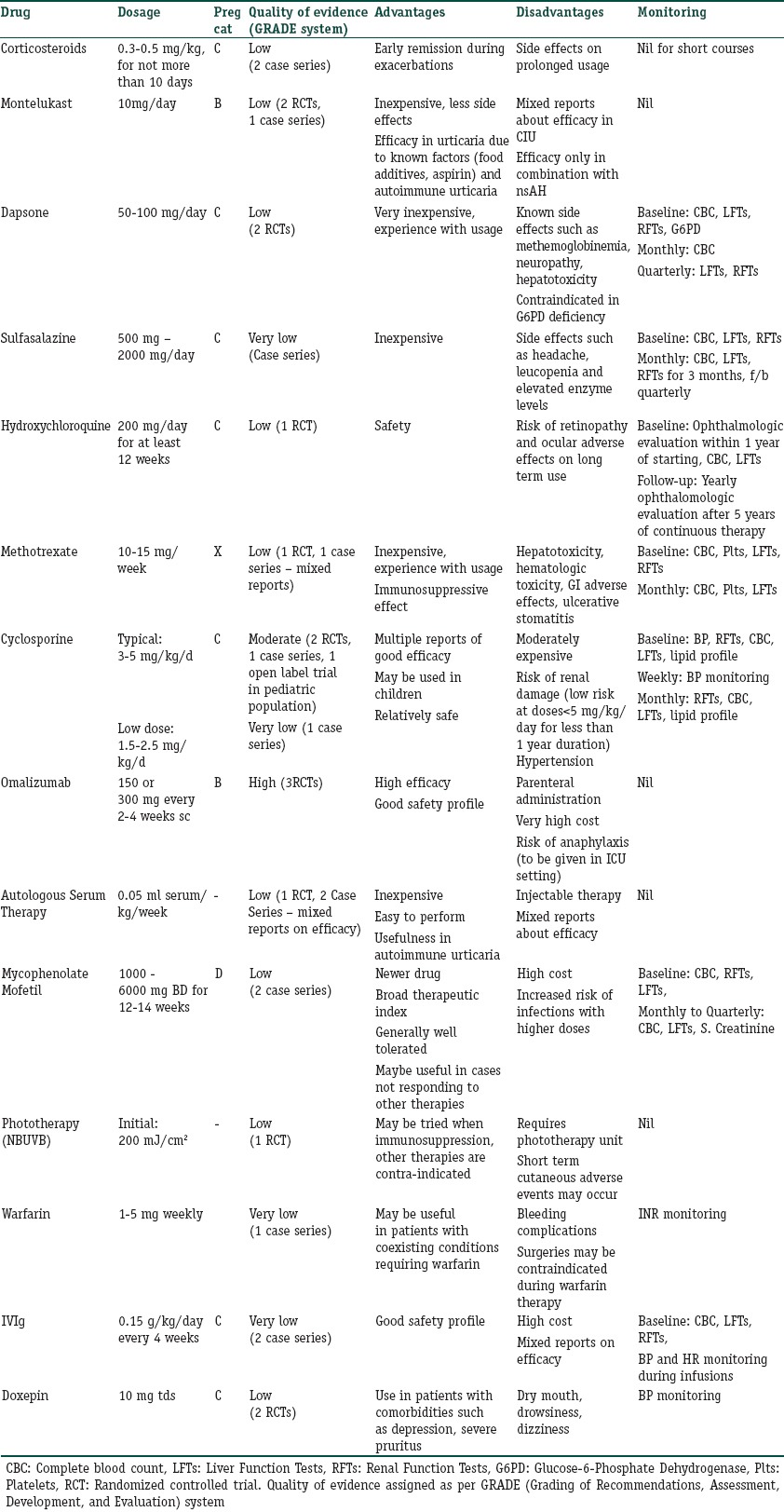

The pregnancy categories of all drugs used in treatment refractory urticaria have been mentioned in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of various agents available for refractory urticaria

Selection of appropriate therapeutic agent

Table 3 gives a compilation of advantages and disadvantages of various drugs available for treatment of chronic refractory urticaria along with the quality of evidence available for that intervention. This will provide a holistic approach to the management of refractory chronic urticaria and help in selection of appropriate agent as per patient profile.

What is new?

Mixed reports on leukotriene antagonists

Systemic corticosteroids recommended only in short courses

Anti-inflammatory agents and cyclosporine A have good efficacy

Weak and unreliable evidence for H2 antagonsists

Methotrexate may not be useful

Reports on efficacy with omalizumab, autologous serum therapy, and MMF

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Gime×nez-Arnau A, Bousquet PJ, Bousquet J, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66:317–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staevska M, Popov T, Kralimarkova T, Lazarova C, Kraeva S, Popova D, et al. The effectiveness of levocetirizine and desloratadine in up to 4 times conventional doses in difficult-to-treat urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asero R, Tedeschi A. Usefulness of a short course of oral prednisone in antihistamine-resistant chronic urticaria: A retrospective analysis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20:386–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asero R, Tedeschi A, Cugno M. Treatment of refractory chronic urticaria: Current and future therapeutic options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:481–8. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godse KV. Severe chronic urticaria treated with oral mini-pulse steroid therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:402–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.74572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pacor ML, Di Lorenzo G, Corroche R. Efficacy of leukotriene receptor antagonist in chronic urticaria: A double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of treatment with montelukast and cetirizine in patients with chronic urticaria with intolerance to food additive and/or acetylsalicylic acid. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1607–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Lorenzo G, Pacor ML, Mansueto P, Esposito Pellitteri M, Lo Bianco C, Ditta V, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial comparing desloratadine and montelukast in monotherapy and desloratadine plus montelukast in combined therapy for chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:619–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagenstose SE, Levin L, Bernstein JA. The addition of zafirlukast to cetirizine improves the treatment of chronic urticaria in patients with positive autologous serum skin test results. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asero R, Tedeschi A, Lorini M. Leukotriene receptor antagonists in chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2001;56:456–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.056005456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godse KV. Oral montelukast monotherapy is ineffective in chronic idiopathic urticaria: A comparison with oral cetirizine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:312–4. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.26735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boehm I, Bauer R, Bieber T. Urticaria treated with dapsone. Allergy. 1999;54:765–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engin B, Özdemir M. Prospective randomized non-blinded clinical trial on the use of dapsone plus antihistamine vs. antihistamine in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:481–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooke A, Morgan M, Rogers L, Huet-Adams B, Khan DA. Double-blind placebo controlled (DBPC) trial of dapsone in antihistamine refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:AB143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGirt LY, Vasagar K, Gober LM, Saini SS, Beck LA. Successful treatment of recalcitrant chronic idiopathic urticaria with sulfasalazine. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1337–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.10.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves GE, Boyle MJ, Bonfield J, Dobson P, Loewenthal M. Impact of hydroxychloroquine therapy on chronic urticaria: Chronic autoimmune urticaria study and evaluation. Intern Med J. 2004;34:182–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ, Hu N. Histamine H2-receptor antagonists for urticaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD008596. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008596.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez A, Woods A, Grattan CE. Methotrexate: A useful steroidsparing agent in recalcitrant chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:191–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sagi L, Solomon M, Baum S, Lyakhovitsky A, Trau H, Barzilai A. Evidence for methotrexate as a useful treatment for steroid dependent chronic urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:303–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godse K. Methotrexate in autoimmune urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma VK, Singh S, Ramam M, Kumawat M, Kumar R. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind pilot study of methotrexate in the treatment of H1 antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:122–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.129382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vena GA, Cassano N, Colombo D, Peruzzi E, Pigatto P. Cyclosporine in chronic idiopathic urticaria: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:705–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godse KV. Cyclosporine in chronic idiopathic urticaria with positive Autologous Serum Skin Test. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:101–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.41662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boubouka C, Charissi C, Kouimintzis D, Kalogeromitros D, Stavropoulos R, Katsarou A. Treatment of autoimmune urticaria with low-dose cyclosporin A: A one-year follow-up. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:50–4. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurer M, Rosén K, Hsieh HJ, Saini S, Grattan C, Gimenéz-Arnau A, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:924–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godse KV. Omalizumab in treatment-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:444. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staubach P, Onnen K, Vonend A, Metz M, Siebenhaar F, Tschentscher I, et al. Autologous whole blood injections to patients with chronic urticaria and a positive autologous serum skin test: A placebo-controlled trial. Dermatology. 2006;212:150–9. doi: 10.1159/000090656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajaj AK, Saraswat A, Upadhyay A, Damisetty R, Dhar S. Autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria: Old wine in a new bottle. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:109–13. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.39691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kocatürk E, Aktaş S, Türkoğlu Z, Kavala M, Zindanci I, Koc M, et al. Autologous whole blood and autologous serum injections are equally effective as placebo injections in reducing disease activity in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: A placebo controlled, randomized, single-blind study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:465–71. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2011.593485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patil S, Sharma N, Godse K. Autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:225–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.110833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahar E, Bergman R, Guttman-Yassky E, Pollack S. Treatment of severe chronic idiopathic urticaria with oral mycophenolate mofetil in patients not responding to antihistamines and/or corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1224–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimmerman AB, Berger EM, Elmariah SB, Soter NA. The use of mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of autoimmune and chronic idiopathic urticaria: Experience in 19 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:767–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engin B, Ozdemir M, Balevi A, Mevlitoglu I. Treatment of chronic urticaria with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:247–51. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahesh PA, Pudupakkam VK, Holla AD, Dande T. Effect of warfarin on chronic idiopathic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:187–9. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.48673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asero R, Tedeschi A, Coppola R, Griffini S, Paparella P, Riboldi P, et al. Activation of the tissue factor pathway of blood coagulation in patients with chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:705–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pereira C, Tavares B, Carrapatoso I, Loureiro G, Faria E, Machado D, et al. Low-dose intravenous gammaglobulin in the treatment of severe autoimmune urticaria. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;39:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asero R. Are IVIg for chronic unremitting urticaria effective? Allergy. 2000;55:1099–101. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan DA. Alternative agents in refractory chronic urticaria: Evidence and considerations on their selection and use. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hollister LE. Tricyclic antidepressants. N Eng J Med. 1978;299:1106–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197811162992004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greene SL, Reed CE, Schroeter AL. Double-blind crossover study comparing doxepin with diphenhydramine for the treatment chronic urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:669–75. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghose S, Haldar S. Therapeutic effect of doxepin in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:218–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellingsen AR, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria with topical steroids an open trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:43–4. doi: 10.2340/00015555764344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barlow RJ, Black AK, Greaves MW, Macdonald DM. The effects of topical corticosteroids on delayed pressure urticaria. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:285–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vena GA, Cassano N, D’Argento V, Milani M. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% in a novel foam formulation is safe and effective in the short-term treatment of patients with delayed pressure urticaria: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:353–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Brzoza Z, Canonica GW, et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: The 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69:868–87. doi: 10.1111/all.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doshi DR, Weinberger MM. Experience with cyclosporine in children with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:409–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]