Abstract

An endeavour to delineate the salient details of the treatment of head lice infestation has been made in the present article. Treatment modalities including over the counter permethrin and pyrethrin, and prescription medicines, including malathion, lindane, benzyl alcohol, spinosad are discussed. Salient features of alternative medicine and physical treatment modalities are outlined. The problem of resistance to treatment has also been taken cognizance of.

Keywords: Head lice, pediculosis capitis, treatment

What was known?

Permethrin, pyrethroids, malathion, lindane, oral ivermectin, cotrimoxazole were known treatments of pediculosis.

Introduction

Pediculosis capitis is one of the most common ectoparasitic infestations, known since time immemorial. Its illustrative evidence comes from the oldest known fossils of louse eggs, approximately 10,000 years old.[1] Children, in the age group of 5-13 years are the usual victims.[2,3] Pediculosis capitis may result in substantial social distress, discomfort, parental anxiety, embarrassment to the child, and unnecessary absence from school and work.[4] There has been a perceptible upsurge of the incidence of pediculosis over the past 3 decades. Besides, there has been a surfacing up of treatment failures due to treatment-resistant lice over the past decades. Pyrethroids, lindane, and to some degree malathion, have been associated with treatment resistance. In this direction, recent approval of benzyl alcohol and spinosad by the United States Food and Drug Administration for treating head lice infestation is a breakthrough. Adjunctive physical modalities also need to be reemphasized. Alternative medicine is being explored.

Methodology

A search was made on Medline/Pubmed (1978-2011) using the key words head lice, pediculosis, permethrin 1%, permethrin 5%, pyrethroids, pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide, malathion, lindane, benzyl alcohol, spinosad, alternative medicine, essential oils, crotamiton, ivermectin, trimethopeim-sulfamethoxazole, cotrimoxazole, physical methods, occlusive therapy, and resistance. In addition, Google search was made using the key words Ayurveda, head lice, and pediculosis. Papers relevant to the current topic in English language were selected. The treatment modalities in vogue have been categorized based on the clinical level of evidence.[1]

Epidemiology

Pediculosis capitis has been well-known since antiquity. School children are commonly afflicted, but refugees, urban slums, child labor, jails, orphanages, and fishing communities are vulnerable too. Although socioeconomic status seems to be an indicator of the magnitude of lice infestation, more specific determinants are the dynamic processes of hygienic status and overcrowding.

Population-based studies in European countries show highly diverging prevalences, ranging from 1% to 20%.[5] In an Indian study, out of a total of 940 study subjects from government run schools, 156 (16.59%) were found to be infested with head louse.[6]

Treatment

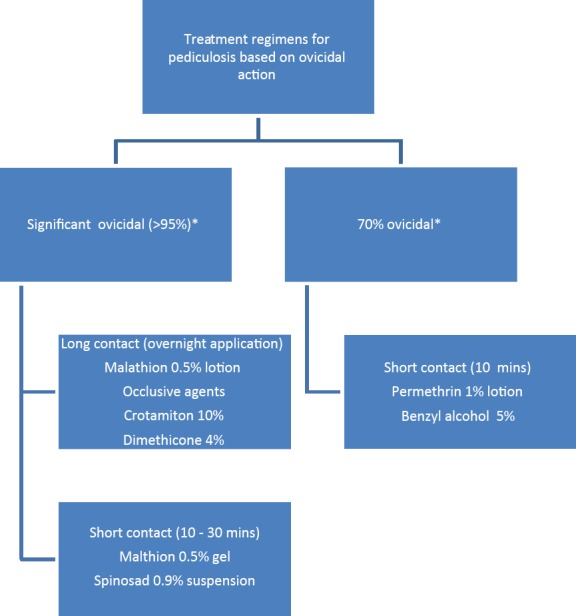

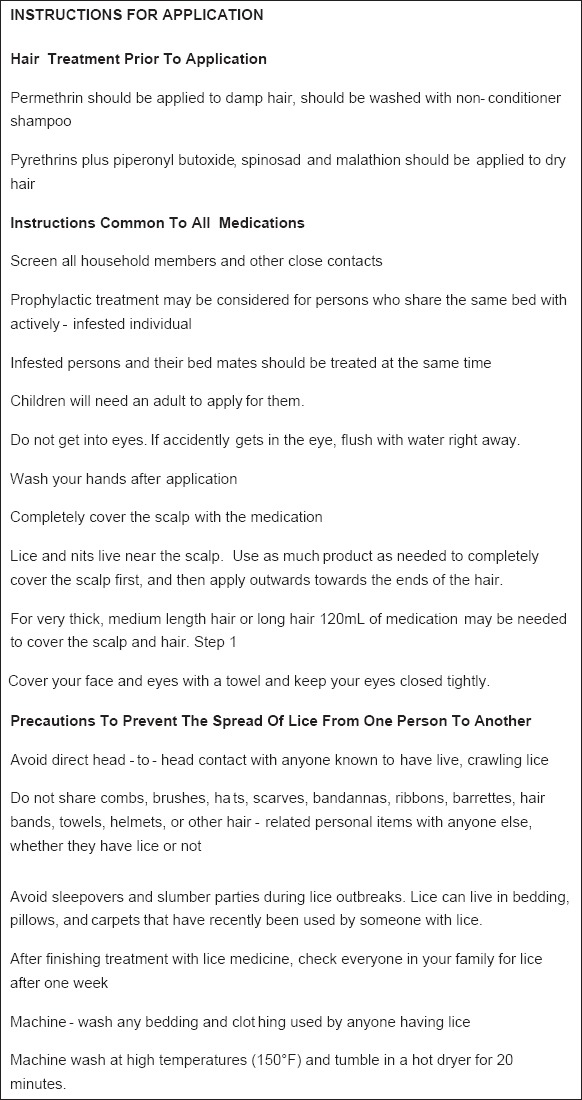

Those with evidence of an active head lice infestation should be treated. Besides, it is imperative to screen all household members and other close contacts. Prophylactic treatment may be considered for persons who share the same bed with actively infested individuals. Akin to scabies, infested persons and their bed mates should be treated at the same time. A practical approach to choosing a pediculicide depending on the ovicidal action and the instructions to their use are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting pediculicides based on ovicidal action

Figure 2.

Instructions for using pediculicides

Choice of a treatment modality for pediculosis should be made considering safety, efficacy, local pattern of resistance, and cost. Following are the various treatment modalities for pediculosis capitis.

Treatment of Pediculosis

Permethrin 1%

It was introduced for the first time in the year 1986 as a scheduled topical agent. Subsequently, 1% permethrin, a synthetic pyrethroid, was approved and was available on counter for use in 1990. Pruritus, erythema, and edema are its usual side effects. It is interesting to note that Permethrin is less allergenic than pyrethrins and does not cause allergic reactions in those with plant allergies. It is applied to damp hair that is first shampooed with a nonconditioning shampoo and then towel dried. It is left on for 10 min and then rinsed off. Permethrin leaves a residue on the hair that is designed to kill nymphs emerging from 20% to30% of the eggs not killed with the first application.[7] However, conditioners and silicone-based additives present in almost all currently available shampoos impair permethrin adherence to the hair shaft and reduce its residual effect.[8] Therefore, the application needs to be repeated in 7-10 days, if live lice are seen. Recent recommendations suggest a re-treatment, preferably on 10th day.[8,9] An alternate treatment schedule on days 0, 7, and 13-15 has been proposed for nonovicidal pediculicides.[10] Resistance to 1% permethrin has been reported,[8,10,11,12,13,14] but its prevalence is unknown. Failure of existing treatments can also be caused by reinfestation, lack of ovicidal killing properties of the product, or noncompliance not following treatment directions, for example, not completely combing out all of the viable nits after treatment.[15] Moreover, adjunctive combing to remove nits, by nonprofessional caregivers may be unreliable.[16]

Malathion 0.5%

0.5% Malathion, a cholinesterase inhibitor, was reintroduced for the treatment of head lice in the United States in the year 1999. Earlier it had to be withdrawn because of prolonged application time, flammability, and odor. It is available as a lotion that is applied to dry hair, left to air dry, then washed off after 8-12 h, with clear-cut instructions to allow the hair to dry naturally; not to use a hair dryer, curling iron, or flat iron while the hair is wet; and not to smoke near a child receiving treatment, for its flammability. It may even be effective with short contact duration of 20 min.[17] Head lice in the United Kingdom and elsewhere have shown resistance to malathion preparations, which have been available for decades in those countries.[18,19] The current US formulation of malathion (Ovide lotion, 0.5%) differs from those available in Europe in that it contains terpineol, dipentene, and pine needle oil, which themselves have pediculicidal properties and may delay the development of resistance.[20] Malathion has high ovicidal activity,[7] and a single application is adequate for most patients. However, the product should be reapplied in 7-9 days if live lice are still seen. Safety and effectiveness of malathion lotion have not been established in children younger than 6 years, and the product is contraindicated in children younger than 2 years. Moreover, it has a theoretic risk of respiratory depression if accidentally ingested, for its cholinesterase inhibitory property. A 30-min application of malathion gel may provide a comparable efficacy, increased safety, and cosmetic acceptability than the lotion form.[21]

Lindane 1%

1% Lindane is available since 1951. It is an organochloride that has central nervous system toxicity; several cases of severe seizures in children using lindane have been reported.[22,23,24,25,26,27] Available as a 1% lindane shampoo, it should be left on the scalp for not more than 4 min, and its reapplication should be in 9-10 days. It has low ovicidal activity (30-50% of eggs are not killed),[8] and resistance has been reported worldwide for many years.[28,29] It should only be used for patients who cannot tolerate or whose infestation has failed to respond to first-line treatment. The Food and Drug Administration has issued a public health advisory concerning the use of lindane, which emphasized that it is a second-line treatment, is contraindicated for use in neonates, and should be used with extreme caution in children and in individuals who weigh less than 50 kg (110 lb) and in those who have HIV infection or take certain medications that can lower the seizure threshold.[30] Lindane is no longer recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (Red Book 2009).[31] All topical pediculicides should be rinsed from the hair over a sink rather than in the shower or bath to limit skin exposure and with warm rather than hot water to minimize absorption attributable to vasodilation.[32]

Permethrin 5% (Permite)

5% Permethrin, available only as a cream, usually applied overnight for scabies for infants as young as 2 months. It has anecdotally been recommended for the treatment of head lice that seem to be recalcitrant to other treatments.[33] No randomized case-control studies have reported efficacy to date. The results of one study suggested that lice resistant to 1% permethrin will not succumb to higher concentrations.[14] Permethrin 5% is not currently approved for use as a pediculicide.

Crotamiton 10%

It has shown to be effective against head lice when applied to the scalp and left on for 24 h before rinsing out.[34] Reports have suggested that 2 consecutive night time applications safely eradicate lice from adults.[35] Safety and absorption in children, adults, and pregnant women have not been evaluated.

Oral ivermectin

It is an anthelmintic agent structurally similar to macrolide antibiotic agents but without antibacterial activity. A single oral dose of 200 μg/kg, repeated in 10 days, has been shown to be effective against head lice.[36] Most recently, a single oral dose of 400 μg/kg repeated in 7 days has been shown to be more effective than 0.5% malathion lotion.[37] It has also been used successfully in school children, 2 doses a week apart.[38] Ivermectin may cross the blood–brain barrier and block essential neural transmission; young children may be at higher risk of this adverse drug reaction. Therefore, ivermectin should not be used for children who weigh less than 15 kg.[39] Ivermectin is also available as a 1% topical preparation. It is applied for 10 min.[19]

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim

The oral antibiotic agent sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim has been cited as effective against head lice.[40] It is postulated that this antibiotic agent kills the symbiotic bacteria in the gut of the louse or perhaps has a direct toxic effect on the louse. Another study showed that prolonged course was needed to free the patients from adult and nymphal stages but not the eggs (nits).[41] The results of a study indicated increased effectiveness when sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim was given in combination with permethrin 1% when compared with permethrin 1% or sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim alone.[42]

Benzyl alcohol 5%

5% Benzyl alcohol was the first nonneurotoxic pediculicide approved for treatment of head lice in children older than 6 months. It is nonneurotoxic and kills head lice by asphyxiation. Pruritus, erythema, pyoderma, and ocular irritation are its usual side effects. It is nonovicidal and should be applied thoroughly so as to saturate the hair and should be left for 10 min and repeated in 7 days,[43] although as with other nonovicidal products, consideration should be given to retreating in 9 days or using 3 treatment cycles (days 0, 7, and 13-15), as mentioned previously.

Spinosad 0.9%

It is a recent advent for topical application. However, it is not yet available in India. It is derived through the fermentation of a naturally occurring organism. Spinosad is a natural mixture of the pediculicidal tetracyclic macrolides spinosyn A and spinosyn D. Spinosad interferes with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in insects, thereby producing neuronal excitation that results in paralysis of lice from neuromuscular fatigue after extended periods of hyperexcitation[44] Spinosad kills both permethrin-susceptible and permethrin-resistant populations of lice. It is also ovicidal, killing both eggs and lice. Systemic absorption was not detectable after a single topical application of spinosad 1.8% for 10 min in children. In randomized, evaluator-blind, multicenter clinical trials, topical spinosad 0.9% without nit combing was significantly more effective than permethrin 1% with nit combing in the eradication of head lice assessed 14 days after 1 or 2 treatments.[45] The majority of subjects treated with spinosad 0.9% without nit combing required only a single treatment to eradicate head lice, whereas the majority of those treated with permethrin 1% with nit combing required 2 treatments. Spinosad is generally innocuous. Cutaneous and ocular irritation are the common adverse events.

Topical ivermectin 0.5% lotion

It is approved for use in children older than 6 months, based on 2 randomized, double-blind phase III clinical trials that compared 10-min application of topical ivermectin with a vehicle control (placebo) in 781 patients from the United States who were 6 months and older. Conjunctivitis, ocular hyperemia, eye irritation, dandruff, dry skin, and skin-burning sensation are the few adverse events, which are rarely encountered.

Pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide

It is derived from natural extracts from the chrysanthemum; pyrethrins are formulated with piperonyl butoxide. Pyrethrins are neurotoxic to lice but have extremely low mammalian toxicity. Their use should be avoided in those allergic to chrysanthemums and ragweed. A pyrethrin–piperonyl–butoxide shampoo was compared with a similarly formulated lotion for their pediculicidal and ovicidal effects against head lice. Although both products proved to be effective in killing lice, the shampoo had a greater ovicidal efficacy, 50% versus 25% for the lotion, after adjustment for natural mortality of the ova.[46]

Pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide is available in shampoo or mousse formulations that are applied to dry hair and left on for[12] minutes before rinsing out. No residual pediculicidal activity remains after rinsing. However, none of them are totally ovicidal against newly laid eggs do not have a nervous system for several days; 20-30% of the eggs remain viable after treatment,[7] which necessitates a second treatment to kill newly emerged nymphs hatched from eggs that survived the first treatment. Moreover, their efficacy has decreased over a period substantially because of emerging resistance, which seems to be variable.[18,47]

Comparison of Pediculicides

A study compared 0.5% malathion with 1% lindane shampoo in pediculosis capitis. Both preparations demonstrated in vitro ovicidal activity, but neither totally abolished post-treatment hatching. No side effects were reported from either preparation.[48] Ovicidal activity and killing times were evaluated for 6 pediculicides, using viable eggs and recently fed head lice from infested children. Four synergized pyrethrin products killed all lice in 10-23 min, and 23-32% of treated eggs hatched; 0.5% malathion lotion killed lice within 5 min and was highly ovicidal, with only 5% of eggs hatching. One percent lindane shampoo was the slowest-acting pediculicide, requiring approximately 3 h to kill all lice; 30% of the eggs hatched after treatment.[7] In a further study 5 years later, there was no significant change in the effectiveness of 0.5% malathion lotion compared with the previous results. On the other hand, there were significant declines in the ovicidal activity of lindane. 1% Permethrin, which was not on the market at the time of the original study, killed lice in less than 30 min, and ovicidal activity ranged from 73% to 90% (diluted and undiluted, respectively).[49] The same group of authors, 1 year later, further evaluated the efficacy of the pediculicides and found the order of effectiveness from most to least effective as follows: Malathion lotion, natural pyrethrin product synergized with piperonyl butoxide, undiluted and diluted 1% permethrin, and 1% lindane shampoo. Malathion was the only pediculicide that had not become less effective.[8] The pediculicidal activity of malathion 0.5% lotion was compared with that of 1% permethrin, in permethrin-resistant head lice, identified by the presence of knockdown resistance-type mutations. Malathion resistance was not observed in this study and it killed the permethrin-resistant head lice approximately 10 times faster than permethrin. A 20-min treatment with malathion, instead of the approved 8- to 12-h application, cured 40 of 41 subjects (98%), demonstrating superior efficacy to 1% permethrin.[17] For difficult-to-treat head lice infestation, oral ivermectin, given twice at a 7-day interval, may be more effective[37] or as efficacious[50] as topical 0.5% malathion lotion. The efficacy and safety of 3 topical pediculicides: A pediculicide containing melaleuca oil (tea tree oil) and lavender oil (TTO/LO); a head lice “suffocation” product; and a product containing pyrethrins and piperonyl butoxide (P/PB), was compared. The percentage of subjects who were louse free after the last treatment with the product containing tea tree oil and lavender oil and the head lice “suffocation” product was significantly higher compared with the percentage of subjects who were louse free 1 day after the last treatment with the product containing pyrethrins and piperonyl butoxide.[51] Furthermore, “suffocation” pediculicide and the melaleuca oil and lavender oil pediculicide (TTO/LO) have been shown to be significantly more ovicidal than eucalyptus oil and lemon tea tree oil pediculicide. The “suffocation” pediculicide and TTO/LO are also highly efficacious against the lice.[52]

Permethrin has been shown to be significantly better than pyrethrins plus piperonyl butoxide for eradicating the lice infestation.[53]

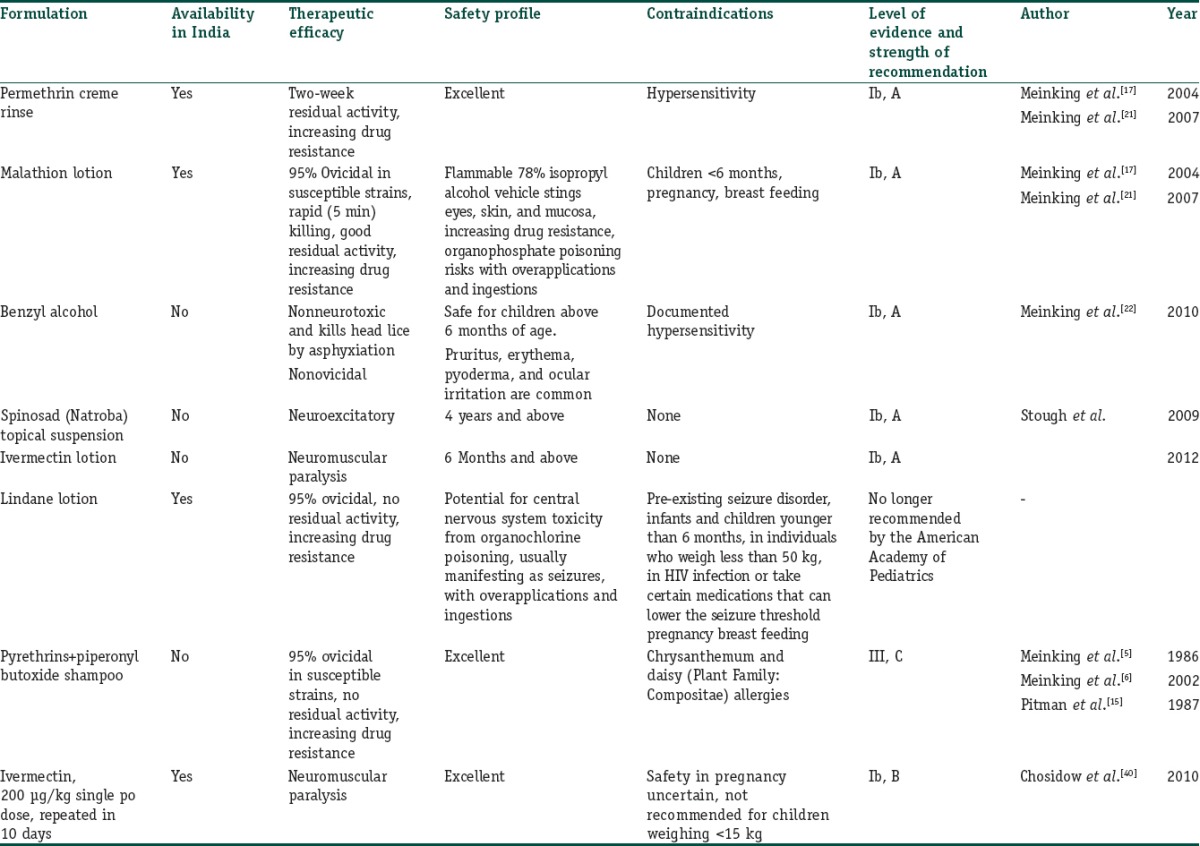

For a glance, the salient details of the recommended pediculicides, evidence-based, are recounted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Treatment of pediculosis capitis: evidence based

Alternative Medicine

Essential oils have been widely used in traditional medicine for the eradication of head lice, but because of the variability of their constitution, the effects may not be reproducible. Several formulations for the treatment of head lice are in vogue. Efficacy of monoterpinoid constituents was assessed in vitro. Terpinen-4-ol was the most effective compound against adult lice, followed by other mono-oxygenated monocyclic compounds, whereas nerolidol was particularly lethal to eggs, but ineffective against adult lice.[54]

In another study, the most effective essential oil against lice in vitro was shown to be tea tree oil; lavender the second most effective, and lemon oil the least. Lotions containing lavender, peppermint, and eucalyptus oils in a 5% composition and the combination of eucalyptus and peppermint in a total concentration of 10%, dissolved in 50% ethanol + isopropanol (1+1) in water have been shown to be effective against permethrin-resistant pediculosis.[55] Eucalyptus sideroxylon, Eucalyptus globulus ssp globulus, and Eucalyptus globulus ssp maidenii have been found to be the most effective Eucalyptus oils against permethrin-resistant pediculosis.[56] The essential oil extracted from rhizomes of Hedychium spicatum was evaluated for in vitro pediculicidal activity. At 5%, 2%, and 1% concentration the essential oil showed more significant activity than 1% permethrin-based product.[57] The efficacy of extract and oil obtained from fruits of Melia azedarach L. was assessed in vitro.[58] The highest lice mortality rate was obtained with a combination of 20% ripe fruit extract with 10% ripe fruit oil. A formulation made with both extract and oil at 10% plus the addition of emulsifier and preserving agents showed 92.3% pediculicidal activity. The products were also successful in delaying or inhibiting nymph emergence.[58] Cinnamomum bark essential oil has got ovicidal and adulticidal properties, which need further exploration.[59]

Besides essential oils, neem (Azadiracta indica) seed extract shampoo proved to be highly effective against all stages of head lice. No obvious differences regarding the efficacy of the shampoo were observed between an exposure time of 10, 15, or 30 min. No side effects, such as skin irritation, burning sensations, or red spots on the scalp, forehead, or neck, respectively, were observed.[60] Grape fruit juice has been seen to have a very quick and efficient activity besides its advantages of being noninflammable, skin safe, and nice smelling.[61]

Ayurveda, Indian system of medicine, recommends a number of medications, including paste of bitter almonds, powder of the bark of Celastrus paniculata (Malakanguni) with mustard oil, paste made of the finely powdered seeds of custard apple (Seetaa-phal) with water, tobacco paste, emulsion of soap-nut (rita), Azadiracta indica (neem), and alum (Phitkari) paste.

Therapies with Physical Mechanisms

Occlusive agents

These are applied to suffocate the lice. They are widely used but have not been evaluated for effectiveness in randomized, controlled trials.

Petroleum jelly massaged on the entire surface of the hair and scalp and left on overnight with a shower cap has been suggested. Diligent shampooing is usually necessary for at least the next 7-10 days to remove the residue. It is thought that the viscous substance obstructs the respiratory spiracles of the adult louse as well as the holes in the operculum of the eggs and blocks efficient air exchange.[62] Another interpretation is that the intense, daily attention to hair grooming results in removal of all the lice and nits. Hair pomades are easier to remove but may not kill eggs, and treatment should be repeated weekly for 4 weeks.[63] Other occlusive substances have been suggested; mayonnaise, tub margarine, herbal oils, and olive oil. Evaluation of several home remedies (vinegar, isopropyl alcohol, olive oil, mayonnaise, melted butter, and petroleum jelly) revealed that the use of petroleum jelly caused the greatest egg mortality, allowing only 6% to hatch.[64] A 96% cure rate has been reported with a suffocation-based pediculicide lotion applied to the hair, dried on with a hand-held hair dryer, left on overnight, and washed out the next morning. The process must be repeated once per week for 3 weeks. The product contained no neurotoxins and did not require nit removal or extensive house cleaning.[65]

Dimethicone

4% Lotion (long-chain linear silicone in a volatile silicone base) in two 8-h treatments, a week apart eradicated head lice in 69% of participants in the United Kingdom.[66] Another study found dimeticone product to be safe and more efficacious than permethrin.[67] Resistance to dimeticone is unlikely due to its physical mode of action.

Isopropyl myristate

50% Solution of isopropyl myristate dissolves the waxy exoskeleton of the louse, resulting in dehydration and death of the louse.[68,69]

Desiccation

The Louse Buster, a custom-built machine uses one 30-min application of hot air. A study showed that subjects had nearly 100% mortality of eggs and 80% mortality of hatched lice.[70] The machine is expensive, and the operator requires special training in its use. A regular blow-dryer should not be used in an attempt to accomplish this result, because it has been shown that wind and blow-dryers can cause live lice to become airborne and, in thus, potentially spread to others in the vicinity.

Manual removal

Removal of nits immediately after treatment with a pediculicide is not necessary to prevent spread, because only live lice cause an infestation. Manual removal of nits (especially the ones within 1 cm of the scalp) after treatment with any product is recommended.[71] Fine-toothed “nit combs” are handy for the purpose.[72,73] Studies have suggested that lice removed by combing and brushing are damaged and rarely survive.[74] In the United Kingdom, community campaigns have been launched using “bug-buster” combs and ordinary shampoo,[75,76] with everyone being instructed to shampoo hair twice per week for 2 weeks and to vigorously comb out wet hair each time. The wet hair seems to slow down the lice. A recent study found that “The Bug Buster kit (1998 version)” was the most effective over-the-counter treatment for head louse infestation in the community when compared with pediculicides.[77] This was unlike the previous study results with “The Bug Buster kit (1996 version)” where malathion was found to be twice as effective as bug busting. Combing dry hair does not seem to have the same effect; a study conducted in Australia in which children combed their hair daily at school with an ordinary comb determined that it was not effective.[78] Some have postulated that vigorous dry combing or brushing in close quarters may even spread lice by making them airborne via static electricity.[79] One study showed that manual removal is not as effective as pediculicides and does not improve results, even when used as an adjunct to pediculicide treatment.[16]

Battery-powered “electronic” louse combs with oscillating teeth are available that claim to remove live lice and nits as well as combs that resemble small bug zappers that claim to kill live lice.[79] No randomized, case-controlled studies have been performed with either type of comb. Their instructions warn not to use on people with a seizure disorder or a pacemaker. Some egg-loosening agents claim to loosen the glue that attaches nits to the hair shaft, thus making the process of nit-picking easier. Vinegar or vinegar-based formulations may be applied to the hair for 3 min before combing out the nits. However, no clinical benefit has been demonstrated[27,63] yet it is not recommended for use with permethrin, as it may interfere with permethrin's residual activity. Although, head shaving could be a simple and effective method to remove the lice and eggs and is in practice in developing countries.

Pediculicide Resistance

The true prevalence of resistance to a particular pediculicide is unknown, and may vary from region to region.[21,24,28,49,80,81,82] Recently, in a German study, coconut and anise spray were found to be significantly more effective than permethrin 0.43% lotion in pediculosis capitis thereby demonstrating clinical resistance.[83]

Amino acid substitutions (Thr929Ile and Leu932Phe) in the alpha subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel are considered to reduce or delay the insecticidal effects of permethrin and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). The DNA sequence bearing the 2 mutations is called the knockdown resistance (kdr)-like gene. However, in the pediculus capitis populations examined, the kdr-like gene does not correlate with failure of permethrin or pyrethrin treatment.[84] An enzyme-mediated malathion-specific esterase is the likely mechanism of lice resistance to malathion.[20]

In the event of treatment failure, it is worthwhile to consider misdiagnosis (no active infestation or misidentification); lack of adherence (patient unable or unwilling to follow treatment protocol); inadequate treatment (not using sufficient product to saturate hair); reinfestation (lice reacquired after treatment); lack of ovicidal or residual killing properties of the pediculicide (eggs not killed can hatch and cause self-reinfestation); and/or resistance of lice to the pediculicide.[85] Spinosad, benzyl alcohol 5% or malathion 0.5% may be used, in case of resistance, for those older than 6 months and 24 months, respectively. However, in younger patients, manual removal or an occlusive therapy is recommended, with emphasis on careful technique and the use of 2-4 properly timed treatment cycles.

What is new?

Spinosad, topical ivermectin, benzyl alcohol, alternative medicines are discussed. Pediculicides have been compared and the problem of pediculicide resistance has been elaborated.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: Developing guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:593–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araújo A, Ferreira LF, Guidon N, Maues Da Serra Freire N, Reinhard KJ, Dittmar K. Ten thousand years of head lice infection. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:269. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janniger CK, Kuflik AS. Pediculosis capitis. Cutis. 1993;51:407–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung AK, Fong JH, Pinto-Rojas A. Pediculosis capitis. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;19:369–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldmeier H. Pediculosis capitis: New insights into epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:2105–10. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khokhar A. A study of pediculosis capitis among primary school children in Delhi. Indian J Med Sci. 2002;56:449–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meinking TL, Taplin D, Kalter DC, Eberle MW. Comparative efficacy of treatments for pediculosis capitis infestations. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:267–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meinking TL, Serrano L, Hard B, Entzel P, Lemard G, Rivera E, et al. Comparative in vitro pediculicidal efficacy of treatments in a resistant head lice population on the US. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:220–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen RC Working Group on the Treatment of Resistant Pediculosis. Guidelines for the treatment of resistant pediculosis. Contemp Pediatr. 2000;17:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics. 2007;119:965–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumcuoglu KY, Hemingway J, Miller J, Ioffe-Uspensky I, Klaus S, Ben-Ishai F, et al. Permethrin resistance in the head louse Pediculus capitis from Israel. Med Vet Entomol. 1995;9:427–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1995.tb00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rupes V, Moravec J, Chmela J, Ledvinka J, Zelenková J. A resistance of head lice [Pediculus capitis] to permethrin in Czech Republic. Cent Eur J Public Health. 1995;3:30–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollack RJ, Kiszewski A, Armstrong P, Hahn C, Wolfe N, Rahman HA, et al. Differential permethrin susceptibility of head lice sampled in the United States and Borneo. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:969–73. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon KS, Gao JR, Lee SH, Clark JM, Brown L, Taplin D. Permethrin-resistant human head lice, Pediculus capitis, and their treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:994–1000. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.8.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frankowski BL, Weiner LB American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on School Health, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2002;110:638–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meinking TL, Clineschmidt CM, Chen C, Kolber MA, Tipping RW, Furtek CI, et al. An observer-blinded study of 1% permethrin creme rinse with and without adjunctive combing in patients with head lice. J Pediatr. 2002;141:665–70. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.129031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitman NK, Hernandez A, Hernandez E. Comparison of pediculicidal and ovicidal effects of two pyrethrin-piperonyl-butoxide agents. Clin Ther. 1987;9:368–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkhart CG. Relationship of treatment-resistant head lice to the safety and efficacy of pediculicides. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:661–6. doi: 10.4065/79.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meinking TL, Vicaria M, Eyerdam DH, Villar ME, Reyna S, Suarez G. Efficacy of a reduced application time of Ovide lotion [0.5% malathion] compared to Nix crème rinse [1% permethrin] for the treatment of head lice. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:670–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downs AM, Stafford KA, Harvey I, Coles GC. Evidence for double resistance to permethrin and malathion in head lice. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:508–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey AM, Prociv P. Persistent head lice following multiple treatments: Evidence for insecticide resistance in Pediculus humanus capitis [letter] Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:146. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2000.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meinking T, Taplin D. Infestations. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, editors. Pediatric Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 1347–92. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenenbein M. Seizures after lindane therapy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:394–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer TF. Lindane toxicity in a 24-year-old woman. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:972–4. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shacter B. Treatment of scabies and pediculosis with lindane preparations: An evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:517–27. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasmussen JE. The problem of lindane. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:507–16. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nolan K, Kamrath J, Levitt J. Lindane Toxicity: A comprehensive review of the medical literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess IF. Human lice and their management. Adv Parasitol. 1995;36:271–342. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60493-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kucirka SA, Parish LC, Witkowski JA. The story of lindane resistance and head lice. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:551–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1983.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA public health advisory: Safety of topical lindane products for the treatment of scabies and lice [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, editors. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediculosis capitis [head lice] pp. 495–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chesney PJ, Burgess IF. Lice: Resistance and treatment. Contemp Pediatr. 1998;15:181–92. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodd CS. Interventions for treating headlice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;3:CD001165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abramowicz M, editor. Drugs for head lice. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1997;39:6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karacic I, Yawalker SJ. A single application of crotamiton lotion in the treatment of patients with pediculosis capitis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:611–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1982.tb02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glaziou P, Nyguyen LN, Moulia-Pelat JP, Cartel JL, Martin PM. Efficacy of ivermectin for the treatment of head lice [pediculosis capitis] Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:253–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, Izri A, Hofmann R, Mann SG, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:896–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Currie MJ, Reynolds GJ, Glasgow NJ, Bowden FJ. A pilot study of the use of oral ivermectin to treat head lice in primary school students in Australia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:595–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Another look at ivermectin in the treatment of scabies and head lice [letter] Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shashindran CH, Gandhi IS, Krishnasamy S, Ghosh MN. Oral therapy of pediculosis capitis with cotrimoxazole. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:699–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb03591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morsy TA, Ramadan NI, Mahmoud MS, Lashen AH. On the efficacy of Co-trimoxazole as an oral treatment for pediculosis capitis infestation. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1996;26:73–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hipolito RB, Mallorca FG, Zuniga-Macaraig ZO, Apolinario PC, Wheeler-Sherman J. Head lice infestation: Single drug versus combination therapy with one percent permethrin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E30. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, Eyerdam DH, Paquet D, Mertz-Rivera K, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% [Ulesfia]: A safe and effective topical treatment for head lice [pediculosis humanus capitis] Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salgado VL. Studies on the mode of action of spinosad: Insect symptoms and physiological correlates. Pesticide Biochem Physiol. 1998;60:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stough D, Shellabarger S, Quiring J, Gabrielsen AA., Jr Efficacy and safety of spinosad and permethrin creme rinses for pediculosis capitis [head lice] Pediatrics. 2009;124:e389–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meinking TL, Vicaria M, Eyerdam DH, Villar ME, Reyna S, Suarez G. A randomized, investigator-blinded, time-ranging study of the comparative efficacy of 0.5% malathion gel versus Ovide Lotion [0.5% malathion] or Nix Creme Rinse [1% permethrin] used as labeled, for the treatment of head lice. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:405–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burkhart C, Burkhart C, Burkhart K. An assessment of topical and oral prescriptions and over-the-counter treatments for head lice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:979–82. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathias RG, Huggins DR, Leroux SJ, Proctor EM. Comparative trial of treatment with Prioderm lotion and Kwellada shampoo in children with head lice. Can Med Assoc J. 1984;130:407–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meinking TL, Entzel P, Villar ME, Vicaria M, Lemard GA, Porcelain SL. Comparative efficacy of treatments for pediculosis capitis infestations: Update 2000. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nofal A. Oral ivermectin for head lice: A comparison with 0.5% topical malathion lotion. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:985–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barker SC, Altman PM. A randomised, assessor blind, parallel group comparative efficacy trial of three products for the treatment of head lice in children-melaleuca oil and lavender oil, pyrethrins and piperonyl butoxide, and a “suffocation” product. BMC Dermatol. 2010;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barker SC, Altman PM. An ex vivo, assessor blind, randomised, parallel group, comparative efficacy trial of the ovicidal activity of three pediculicides after a single application-melaleuca oil and lavender oil, eucalyptus oil and lemon tea tree oil, and a “suffocation” pediculicide. BMC Dermatol. 2011;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carson DS, Tribble PW, Weart CW. Pyrethrins combined with piperonyl butoxide [RID] vs 1% permethrin [NIX] in the treatment of head lice. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142:768–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150070082031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Priestley CM, Burgess IF, Williamson EM. Lethality of essential oil constituents towards the human louse, Pediculus humanus, and its eggs. Fitoterapia. 2006;77:303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez Audino P, Vassena C, Zerba E, Picollo M. Effectiveness of lotions based on essential oils from aromatic plants against permethrin resistant Pediculus humanus capitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:389–92. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toloza AC, Lucía A, Zerba E, Masuh H, Picollo MI. Eucalyptus essential oil toxicity against permethrin-resistant Pediculus humanus capitis [Phthiraptera: Pediculidae] Parasitol Res. 2010;106:409–14. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jadhav V, Kore A, Kadam VJ. In-vitro pediculicidal activity of Hedychiumspicatum essential oil. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:470–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carpinella MC, Miranda M, Almirón WR, Ferrayoli CG, Almeida FL, Palacios SM. In vitro pediculicidal and ovicidal activity of an extract and oil from fruits of Melia azedarach L. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:250–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang YC, Lee HS, Lee SH, Clark JM, Ahn YJ. Ovicidal and adulticidal activities of Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark essential oil compounds and related compounds against Pediculus humanus capitis [Anoplura: Pediculicidae. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abdel-Ghaffar F, Semmler M. Efficacy of neem seed extract shampoo on head lice of naturally infected humans in Egypt. Parasitol Res. 2007;100:329–32. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abdel-Ghaffar F, Semmler M, Al-Rasheid K, Klimpel S, Mehlhorn H. Efficacy of a grapefruit extract on head lice: A clinical trial. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:445–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schachner LA. Treatment resistant head lice: Alternative therapeutic approaches. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:409–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1997.tb00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Pchalek I, Arbogast J. The adherent cylindrical nit structure and its chemical denaturation in vitro: An assessment with therapeutic implications for head lice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:711–2. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.7.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takano-Lee M, Edman JD, Mullens BA, Clark JM. Home remedies to control head lice: Assessment of home remedies to control the human head louse, Pediculus humanus capitis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2004;19:393–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pearlman DL. A simple treatment for head lice: Dry-on, suffocation-based pediculicide. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e275–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0666-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burgess IF, Brown CM, Lee PN. Treatment of head louse infestation with 4% dimethicone lotion: Randomized controlled equivalence trial. BMJ. 2005;330:1423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38497.506481.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heukelbach J, Pilger D, Oliveira FA, Khakban A, Ariza L, Feldmeier H. A highly efficacious pediculicide based on dimeticone: Randomized observer blinded comparative trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burgess LF, Lee PN, Brown CM. Randomised, controlled, parallel group clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of isopropyl myristate/cyclomethicone solution against head lice. Pharmaceut J. 2008;280:371–5. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaul N, Palma KG, Silagy SS, Goodman JJ, Toole J. North American efficacy and safety of a novel pediculicide rinse, isopropyl myristate 50% [Resultz] J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11:161–7. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goates BM, Atkin JS, Wilding KG, Birch KG, Cottam MR, Bush SE, et al. An effective nonchemical treatment for head lice: A lot of hot air. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1962–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ibarra J, Hall DM. Head lice in school children. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:471–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.75.6.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bainbridge CV, Klein GL, Neibart SI, Hassman H, Ellis K, Manring D, et al. Comparative study of the clinical effectiveness of a pyrethrin-based pediculicide with combing versus permethrin based pediculicide with combing. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998;37:17–22. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burkhart CN, Arbogast J. Head lice therapy revisited [letter] Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998;37:395. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chunge RN, Scott FE, Underwood JE, Zavarella KJ. A review of the epidemiology, public health importance, treatment and control of head lice. Can J Public Health. 1991;82:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maunder JW. Updated community approach to head lice. J R Soc Health. 1988;108:201–2. doi: 10.1177/146642408810800604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Plastow L, Luthra M, Powell R, Wright J, Russell D, Marshall MN. Head lice infestation: Bug busting vs. traditional treatment. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:775–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hill N, Moor G, Cameron MM, Butlin A, Preston S, Williamson MS, et al. Single blind, randomised, comparative study of the Bug Buster kit and over the counter pediculicide treatments against head lice in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 2005;331:384–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38537.468623.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Monheit BM, Norris MM. Is combing the answer to head lice? J Sch Health. 1986;56:158–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1986.tb05728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O’Brien E. Detection and removal of head lice with an electronic comb: Zapping the louse! J Pediatr Nurs. 1998;13:265–6. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(98)80055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02729-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hunter JA, Barker SC. Susceptibility of head lice [Pediculus humanus capitis] to pediculicides in Australia. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:476–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0881-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bartels CL, Peterson KE, Taylor KL. Head lice resistance: Itching that just won’t stop. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:109–12. doi: 10.1345/aph.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burgess IF, Brunton ER, Burgess NA. Clinical trial showing superiority of a coconut and anise spray over permethrin 0.43% lotion for head louse infestation, ISRCTN96469780. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-0978-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bialek R, Zelck UE, Fölster-Holst R. Permethrin treatment of head lice with knockdown resistance-like gene. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:386–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1007171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frankowski BL, Bocchini JA, Jr Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:392–403. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]