Abstract

Background and Purpose

Targeted modulation of autophagy induced by myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion has been the subject of intensive investigation, but it is debatable whether autophagy is beneficial or harmful. Hence, we evaluated the effects of pharmacological manipulation of autophagy on the survival of cardiomyocytes in different time windows of ischaemia/reperfusion.

Experimental Approach

We examined the autophagy and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes subjected to different durations of anoxia/re-oxygenation or ischaemia/reperfusion, and evaluated the effects of the autophagic enhancer rapamycin and inhibitor wortmannin on cell survival.

Key Results

In neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCs) or murine hearts, autophagy was increased in response to anoxia/reoxygenation or ischaemia/reperfusion in a time-dependent manner. Rapamycin-enhanced autophagy in NRCs led to higher cell viability and less apoptosis when anoxia was sustained for ≦6 h. When anoxia was prolonged to 12 h, rapamycin did not increase cell viability, induced less apoptosis and more autophagic cell death. When anoxia was prolonged to 24 h, rapamycin increased autophagic cell death, while wortmannin reduced autophagic cell death and apoptosis. Similar results were obtained in mice subjected to ischaemia/reperfusion. Rapamycin inhibited the opening of mitochondrial transition pore in NRCs exposed to 6 h anoxia/4 h re-oxygenation but did not exert any effect when anoxia was extended to 24 h. Similarly, rapamycin reduced the myocardial expression of Bax in mice subjected to short-time ischaemia, but this effect disappeared when ischaemia was extended to 24 h.

Conclusions and Implications

The cardioprotection of autophagy is context-dependent and therapies involving the modification of autophagy should be determined according to the duration of ischaemia/reperfusion.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Caspase 3 |

| mTOR |

| PI3K |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| Rapamycin |

| Wortmannin |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

Irreversible loss of cardiomyocytes is the major cause of myocardial injury induced by ischaemia or ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R), which leads to persistent cardiac dysfunction and heart failure. Necrosis, apoptosis and autophagy are known to contribute to the loss of cardiomyocytes in hearts exposed to I/R insult; of them, autophagy, a lysosome-mediated recycling of long-lived proteins and damaged cells, plays a key role in the degradation and turnover of mitochondria and other organelles, but it is a subject of much debate whether autophagy is beneficial or detrimental during myocardial ischaemia or I/R (Aki et al., 2003; Gustafsson and Gottlieb, 2009; Sciarretta et al., 2011). Autophagy can either improve survival or accelerate death in different situations. Basic autophagic activity is vital for homeostasis including maintaining the cell size, construction and function of cardiomyocytes. Autophagic activity is up-regulated in cardiomyocytes during anoxia/reoxygenation (A/R) and in myocardium subjected to I/R. Many studies support the notion that enhanced autophagy is cardioprotective (Matsui et al., 2007; Kanamori et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013), while there is also substantial evidence supporting the hypothesis that increased autophagy is detrimental to cardiomyocytes (Valentim et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2009). There is so much debate on the function of autophagy in I/R, one of the reasons may be the limitation of research design. Relevant studies in the literature are mostly focused on one I/R setting, in only a few has comparative research been performed on multiple I/R settings in one study. Although it has been hypothesized that either too much or too little autophagy is harmful (Nishida et al., 2008), few authors have confirmed this simultaneously in one study. If this hypothesis is true, then genetic approaches, including gene knockout and overexpression through which autophagy will be too much or too little, will not be feasible for finding the ‘ideal level’ of autophagy. If the ‘safety range’ of autophagy during myocardial I/R injury could be determined, it is then possible to achieve the therapeutic goal by controlling autophagy using a pharmacological approach. In eukaryotic cells, rapamycin enhances autophagy by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), while 3-methyladenine or wortmannin attenuates autophagy by inhibiting the PI3K. Clinically, it seems plausible to preserve the physiologically beneficial autophagy and eliminate the excessive autophagy through pharmacological modulation.

It is recognized that there is a cross-talk between autophagy and apoptosis, both of which are closely associated with mitochondrial function. Mitochondria are important gatekeepers of the life and death of the cell. It is well known that myocardial I/R might lead to mitochondrial dysfunction. Apoptosis can be induced through the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and the release of pro-death proteins. Autophagy is reported to be involved in the removal of damaged mitochondria, which will reduce necrotic or apoptotic cell death. However, excessive autophagy may also result in the depletion of mitochondria and other organelles, which is thought to be the cause of autophagic cell death. Whether a change in autophagy activity will influence mitochondrial permeability, thereby affecting myocardial function, will be an important factor when choosing the intervention drugs.

Thus, in this study, we firstly examined the autophagic activity in cardiomyocytes subjected to different durations of ischaemia or anoxia stimulation both in vivo and in vitro. Secondly, we determined the role of autophagy in cell death during ischaemia or I/R by manipulating autophagy with rapamycin or wortmannin. Finally, we investigated the molecular mechanisms of the cell death associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis.

Methods

Approval for this study was granted by the ethics review board of our university. All procedures were performed in accordance with our Institutional Guidelines for Animal Research and the investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised in 1996). The dose and concentration of rapamycin and wortmannin were determined according to previous reports (Fujio et al., 2000; Ng et al., 2001; Hirota et al., 2011; Kobayashi et al., 2012) and our preliminary experiments. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Isolation and culture of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCs)

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from 1- to 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously (Liao et al., 2005; Xuan et al., 2012). The isolated cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma, Shanghai, China) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 3–4 days before exposure to A/R or treatment with wortmannin or rapamycin. 5-Bromo-2-deoxyuridine was added to inhibit fibroblast proliferation, and cell types were confirmed using immunochemistry as previously reported (Xuan et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2014). For A/R experiments, cardiomyocytes were incubated with rapamycin (0.1 μM), wortmannin (0.2 μM) or DMSO for 30 min, and then plated in an anoxia chamber (0.1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94.9% N2) for 6, 12 and 24 h, respectively, followed by reoxygenation in a normoxia chamber (21% O2, 5% CO2 and 74% N2) for 4 h. Three A/R groups and three corresponding normoxia groups were designed (three A/R groups were A 6 h/R 4 h, A 12 h /R 4 h and A 24 h/R 4 h, while normoxia groups were normoxia for 10 h, 16 h and 24 h respectively). Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay as described previously (Ghavami et al., 2010; Xuan et al., 2012). The cell viability was calculated using the formula: (mean OD value of treated cells/mean OD value of control cells) × 100%.

Construction of recombinant adenovirus carrying short hairpin RNA (shRNA) of beclin-1 (Ad-sh-beclin-1)

Ad-sh-beclin-1 and Ad-scramble were generated by a professional company (Vigene Biosciences, Shandong, China). The hairpin-forming oligo, corresponding to bases (5′-CAATTTGGCACGATCAATATTCAAGAGATATTGATCGTGCCAAATTGCTTTTTTTT-3′) of the rat beclin 1 cDNA were synthesized, annealed and subcloned distal to the U6 promoter of pSH-U6-GFP shuttle vector. A mutant oligo including two mismatch mutations was also generated for use as a control (scramble). And then, the recombinant adenovirus pAD-Kan-SH-U6-GFP-shRNA-beclin-1 was generated, collected and amplified in HEK293 cells.

Labelling of autophagic vacuoles with MDC

MDC staining was performed as reported previously (Xuan et al., 2012). Briefly, the cells were incubated with 50 μM MDC in PBS at 37°C for 10 min. After incubation, cells were washed four times with PBS and immediately analysed with a fluorescence microscope (excitation 380–420 nM, barrier filter 450 nM).

Hoechst 33258 staining

Apoptosis was quantified by detection of condensed chromatin with the fluorochrome, Hoechst 33258, as previously described (Isenberg and Klaunig, 2000; Luo et al., 2013) with modifications. Following the selected treatment duration, cardiomyocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 10 min and washed twice in PBS. Cells were then stained with Hoechst 33258 for 5 min and washed twice in PBS. Then, cells were visualized with a fluorescence microscope (excitation 350 nM, emission fluorescent filter 460 nM). Apoptotic cells were identified morphologically by the strong nuclear staining of Hoechst 33258 as an indication of DNA fragmentation and nuclear shrinkage. Cells were counted from each optical field to calculate the percentage cell death in comparison with control.

Mitochondrial permeability and depolarization assay

mPTP in cardiomyocytes was assessed using the calcein/CoCl2 method as described previously (Baines et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2013). The combination of these two reagents results in selective staining of mitochondria. mPTP allows the efflux of calcein into the cytosol where calcein is quenched by CoCl2. Thus, a loss of mitochondrial fluorescence is an indication of mPTP.

After the indicated treatments, cardiomyocytes were co-loaded with 1 μM calcein AM and 1 mM CoCl2 at room temperature for 20 min, and then washed three times. Cells were visualized with a confocal laser scanning microscope or read with a fluorometer at 488 nM excitation, 515 nM emission.

The mitochondrial membrane potential ΔΨm was estimated as described elsewhere (Faghihi et al., 2008). Briefly, after A/R, cells were stained with the fluorescent probe JC-1 for 30 min at 37°C, and then washed three times in PBS. Fluorescence was viewed at a 488 nM excitation wavelength, and emission was captured at 530 and 590 nM for green and red channels, respectively, and the JC-1 ratio always refers to the green/red ratio.

Model of myocardial ischaemia or I/R

C57BL/6 male mice (10–12 weeks, weighing 22–29 g, n = 142) were anaesthetized with a mixture of xylazine (5 mg·kg−1) and ketamine (100 mg·kg−1), injected i.p., and ventilated and the adequacy of anesthesia was monitored from the disappearance of pedal withdrawal reflex. After left thoracotomy, the left coronary artery was ligated 2 mm below the left atrial appendage. Following 15 or 40 min of coronary occlusion, the ligature was removed and the heart was reperfused for 24 h. In mice assigned to the groups with ischaemia for 24 h, coronary occlusion was maintained for 24 h without reperfusion (the ligature was not removed). The electrocardiogram was monitored to document ST-segment elevation during coronary occlusion. Sham-operated mice underwent the same procedure except that their left coronary artery was not occluded. All mice in the I/R groups and sham group survived for 24 h. In mice with ischaemia for 24 h, the mortality was 12.5% (2 in 16), 12.5% (2 in 16) and 17.6% (3 in 17) in the DMSO-, wortmannin- and rapamycin-treated groups respectively (P > 0.05). Hence, we designated the duration for myocardial ischaemia plus reperfusion as 24 h/0 min, 15 min/24 h and 40 min/24 h, respectively, only one sham group for 24 h was designated (it was assumed that there should be no significant difference among sham groups with perfusion for 24 h, 24 h 15 min and 24 h 40 min). Myocardial infarct size was determined by 1% TTC staining, while area at risk was determined with Evans blue staining by i.v. injection into the jugular vein. Rapamycin (0.25 mg·kg−1), wortmannin (0.6 mg·kg−1) or saline was injected i.p. 1 h before surgery.

Western blot

Proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The blot was blocked at room temperature for 2 h with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% non-fat milk and then probed with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The blot was washed (3 × 10 min) with TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000) at room temperature for 2 h. Blots were washed (3 × 10 min) with TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, revealed by ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) in a Western blotting detection system (Kodak Digital Science, Rochester, NY, USA) and quantified by densitometry using the Image J analysis software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Ultrastructure examination with an electronic microscope

Cardiac tissue was quickly cut into 1 mm cubes, tissue samples or cultured cardiomyocytes were immersion-fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C and post-fixed in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide for 1.5 h. Samples were contrasted with 5% uranyl acetate for 2 h, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and embedded in epoxy resin. The specimens were conventionally processed and examined under an electronic microscope (H-800; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was analysed by using Student's unpaired t-test or one-way anova, followed by Bonferroni's correction for post hoc multiple comparisons. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Agents

Rapamycin, 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), calcein, wortmannin, bafilomycin A1 (Baf), monodansylcadaverine (MDC), triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) were purchased from Sigma (Shanghai, China). Antibodies against LC3 I/II, Atg 5, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and phosphorylated-mTORC1 (p-mTORC1) were from Cell Signal Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); antibodies against beclin-1, Bax and β-actin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA); the antibody against cleaved caspase 3 was from (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase was from Bio-Rad (Shanghai, China).

Results

Autophagy triggered by A/R in cultured cardiomyocytes

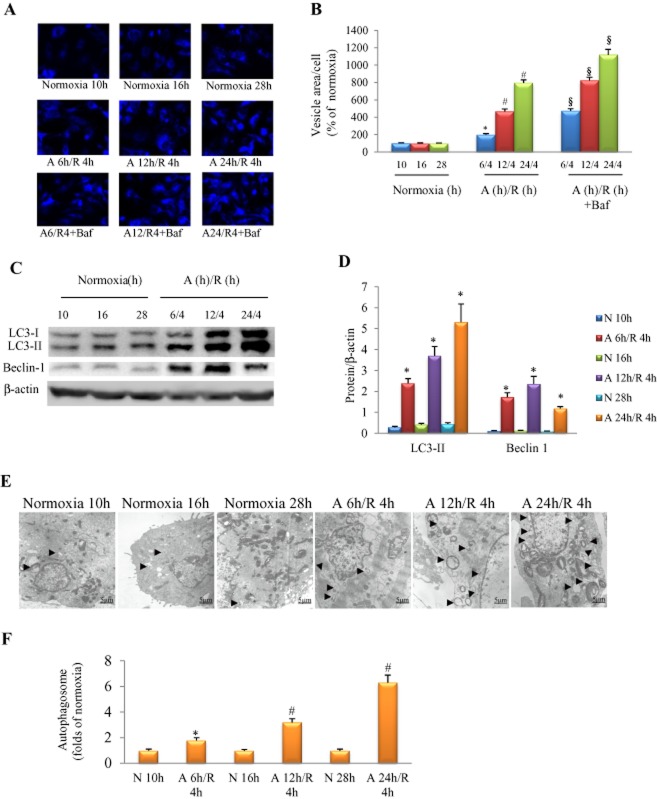

We evaluated autophagy in cultured NRCs subjected to different durations of anoxia. MDC was used to label acidic endosomes, lysosomes and autophagosomes, and LC3-II protein expression was used to monitor autophagic activity. We noticed that A6-24 h/R4 h strongly activated autophagy, as indicated by a time-dependent increase in MDC-positive vacuoles (Figure 1A, B) and expression of LC3-II and beclin 1 proteins (Figure 1C, D). Treatment with bafilomycin A1 (0.1 μM) further increased MDC-positive vacuoles in cardiomyocytes exposed to A6-24 h/R4 h, suggesting that A/R increased autophagic flux (Figure 1A, B). Induction of autophagy was also confirmed using electronic microscopy. Under normoxia, autophagosome was merely detectable, whereas the autophagosome was increased when the anoxia duration was extended (Figure 1E, F).

Figure 1.

Autophagy triggered by A/R in cultured NRCs. (A) Autophagic activity detected by MDC stain in the presence/absence of bafilomycin A1 (Baf, 0.1 μM). (B) Area of MDC-positive vesicle per cell, n = 6 in each group. (C) Examples of Western blotting picture of autophagy-related proteins. (D) Quantitative analysis of LC3-II, and beclin-1; n = 5, in each group. (E) Autophagic vesicle (arrow) increased in an anoxia duration-dependent manner. (F) Quantitative analysis of autophagic vacuole (the number of autophagosome per optical field, 30 optical fields were used to calculate and results standardized to the responding normoxia group), n = 5 in each group. In (B, D and F), *P < 0.05 versus the corresponding normoxia group; #P < 0.05 versus A 6 h/R 4 h group; §P < 0.05 versus the corresponding A/R group without bafilomycin A1 treatment. N, normoxia.

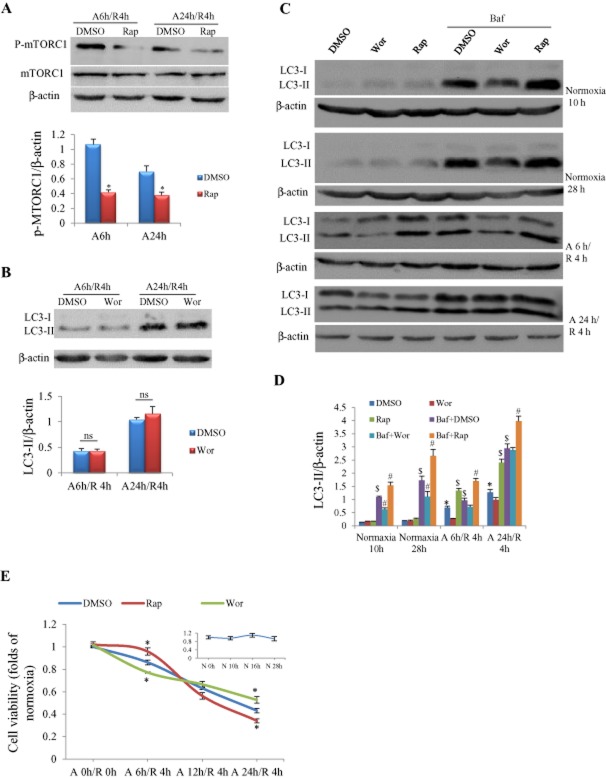

Influence of pharmaceutical manipulation of autophagy on autophagic flux and cell viability

Cultured cardiomyocytes were incubated with rapamycin or wortmannin for 30 min before anoxia was initiated. We firstly confirmed that rapamycin at 0.1 μM significantly inhibited the activation of mTORC1 in cardiomyocytes subjected to A/R (Figure 2A), which is the pharmacological mechanism by which the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin acts as an autophagic enhancer. It was reported that wortmannin at low concentrations (IC50 = 3.0 nM) in rat basophilic leukaemia 2H3 cells can inhibit PI3K upstream of mTOR (Yano et al., 1993); we examined its effect on autophagy. We noted that wortmannin at 3 nM exerted no influence on LC3-II expression in cardiomyocytes (Figure 2B), thus we chose 0.2 μM as an autophagic inhibitory concentration according to a previous report (Vanrell et al., 2013). We found that autophagy induced by anoxia was enhanced by rapamycin and was suppressed by wortmannin, as indicated by Western blotting of LC3-II, and it was further increased by addition of the lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (Figure 2C and D). The cell viability assessed by MTT showed a progressive decrease as anoxia duration was extended from 6 to 24 h (Figure 2E). The majority of cardiomyocytes (57%) were dead in response to A/R for 24 h/4 h (Figure 2E). In cardiomyocytes exposed to A/R for 6 h/4 h, the cell viability was higher in the rapamycin-treated group and lower in the wortmannin-treated group than in the DMSO-treated group (Figure 2E). When A/R was prolonged to 12 h/4 h, co-treatment with rapamycin or wortmannin exerted no significant influence on cell viability. However, when A/R duration was extended to 24 h/4 h, the cell viability was increased by wortmannin and decreased by rapamycin (Figure 2E). There were no significant differences in the cell viability among groups with corresponding normoxia durations.

Figure 2.

Influences of autophagy manipulation on autophagic flux and viability of NRCs in response to A/R. (A) Rapamycin (Rap) at 0.1 μM significantly inhibited phosphorylation of mTOR in cardiomyocytes with A/R insults. *P < 0.05, n = 5. (B) Wortmannin (Wor) at 3 nM had no effect on LC3-II protein expression. Experiments were repeated five times; ns, not significant. (C) Representative pictures of Western blot for LC3-II in response to A/R with/without autophagy manipulation. (D) Semi-quantification of LC3-II protein expression as shown in (C). Rapamycin = 0.1 μM; wortmannin = 0.2 μM; bafilomycin A1 (Baf) = 0.1 μM. *P < 0.05 versus the DMSO group at the corresponding time point of normoxia; #P < 0.05 versus the bafilomycin A1 + DMSO group at the same time point; $P < 0.05 versus the DMSO group at the same time point, n = 5. (E) Viability of cardiomyocytes measured by MTT assay. *P < 0.05, n = 24, 6 and 6 in control (DMSO), rapamycin and wortmannin groups respectively. The insert figure shows cell viability in response to different normoxia duration, n = 6 at each time point.

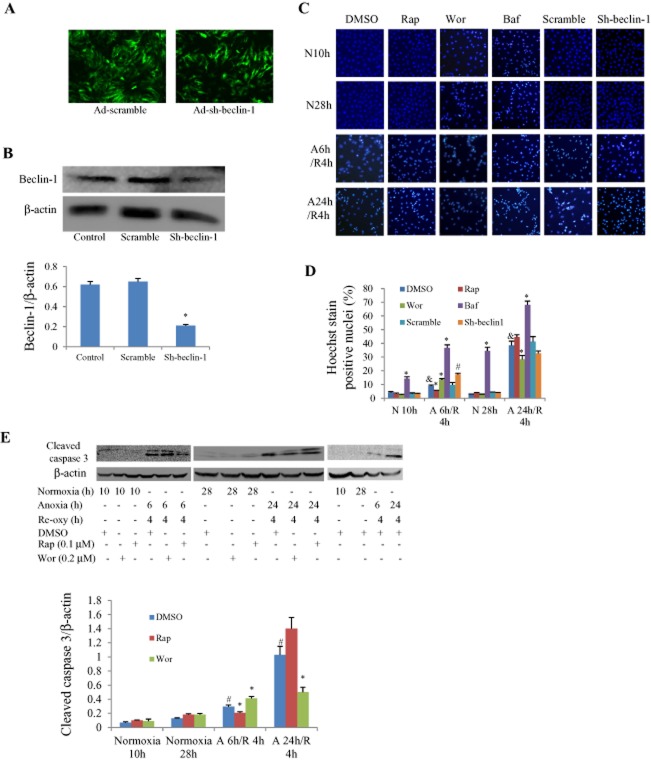

Furthermore, we examined whether the cell death was associated with apoptosis or autophagy by using both a pharmacological and genetic approach. Ad-sh-beclin-1 or Ad-scramble had a satisfactory infective efficiency and beclin-1 protein level was knocked-down by about 70% (Figure 3A and B). Apoptosis assessed by Hoechst 33258 staining was increased in an anoxia duration-dependent manner. When the anoxia duration was less than 12 h, rapamycin reduced the number of apoptotic cells while wortmannin increased it; this was reversed when anoxia was prolonged to 24 h (Figure 3C and D). The addition of bafilomycin A1 further increased cell apoptosis, while knockdown of beclin-1 produced an effect similar to wortmannin (Figure 3C and D). Similar results were obtained by observing the expression levels of cleaved caspase 3 (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Effects of pharmacological and genetic manipulation of autophagy on apoptosis in cultured NRCs with different durations of A/R. (A) Infective efficiency of adenovirus carrying shRNA for beclin-1 (Ad-sh-beclin-1) or control (Ad-scramble) in cultured cardiomyocytes for 48 h detected by the green fluorescence of co-expressed EGFP, multiple of infection = 5. (B) Western blot analysis of beclin-1 protein levels in response to Ad-sh-beclin-1 or Ad-scramble infection (*P < 0.01 vs. scramble group. The experiment was repeated five times). (C) Representative Hoechst staining pictures under microscope. The bright blue-stained nucleolus represent apoptotic cells. (D) Apoptotic rate calculated from five fields of view for each group. &P < 0.05 versus the corresponding DMSO group under normoxia (N 10 h or N 28 h), *P < 0.05 versus the corresponding DMSO group. #P < 0.05 versus the corresponding scramble group. Experiments were repeated five times. (E) Western blotting results of cleaved caspase 3. #P < 0.05 versus the corresponding DMSO group under normoxia (N 10 h or N 28 h), *P < 0.05 versus the corresponding DMSO group. Experiments were repeated five times. Concentration used: wortmannin (Wor) 0.2 μM; rapamycin (Rap) 0.1 μM; bafilomycin A1 (Baf) 0.1 μM. N, normoxia; Re-oxy, reoxygenation.

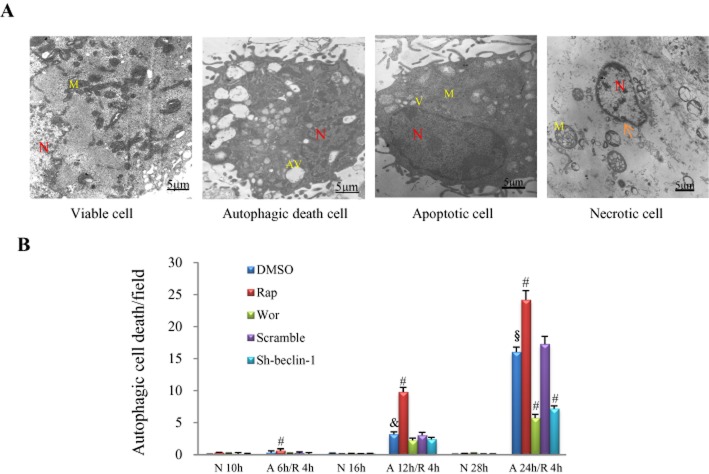

Electronic microscopy was used to quantify the autophagic cell death, characterized by the massive accumulation of autophagic vacuoles (autophagosomes) in the cytoplasm of cells (Figure 4A). Apoptotic and necrotic cardiomyocytes were also detectable. Apoptotic ultrastructure was characterized by cytoplasmic shrinkage with an intact plasma membrane, nuclear condensation and the appearance of vacuoles, while necrotic cells were characterized by swollen mitochondria and the disruption of the plasma membrane (Figure 4A). The number of cells affected by autophagic death was only 0.31 per optical field in cells subjected to A/R for 6 h/4 h, and it was slightly increased to 0.63 per optical field by rapamycin pretreatment (P < 0.05, Figure 4B). Autophagic cell death was markedly increased to about 3 and 16 per optical field when the anoxia duration was prolonged to 12 and 24 h respectively (P < 0.01; Figure 4B). Rapamycin significantly enhanced while wortmannin suppressed autophagic cell death as anoxia duration persisted for 12 h or more, and silencing of beclin-1 produced an effect similar to wortmannin (P < 0.01; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Influence of A/R and autophagic manipulation on autophagic cell death in NRCs. (A) Examples of viable, autophagic, apoptotic and necrotic cardiomyocytes under electronic microscopy. N, nucleus; M, mitochondria; AV, autophagic vacuole; arrow, disruption of plasma membrane. (B) Number of cells detected undergoing autophagic death in response to different severities of A/R and treatment with rapamycin (Rap, 0.1 μM) or wortmannin (Wor, 0.2 μM) or adenovirus carrying sh-beclin 1 or scramble. &P < 0.05 versus the DMSO group with insult of A 6 h/R 4 h; §P < 0.05 versus the DMSO group with insult of A 12 h/R 4 h; #P < 0.05 versus the DMSO group with the same insult, n = 5 in each group. N, normoxia.

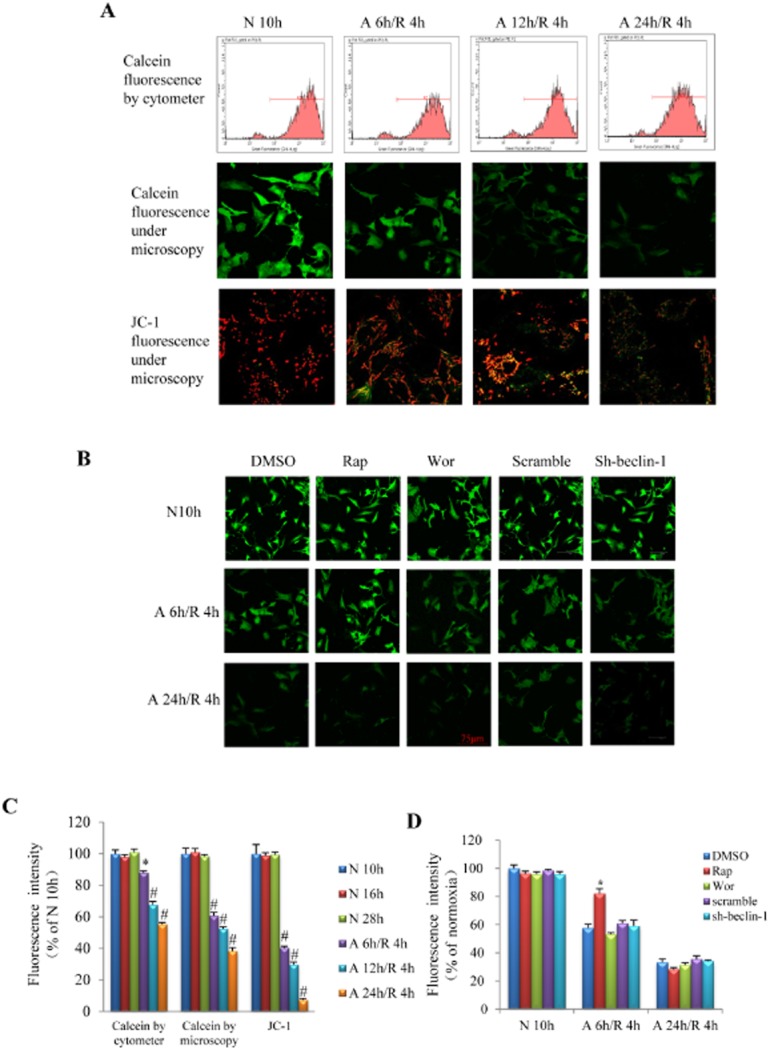

Influence of autophagy on ΔΨm and opening of mPTP

Considering the important role of mitochondria in the three types of cell death, we evaluated ΔΨm by JC-1 probing and mPTP opening by calcein staining in anoxic NRCs. We found that ΔΨm depolarization was induced by anoxia for 6 h in NRCs, which was further increased when the anoxia duration was prolonged to 12 and 24 h (Figure 5A, C). Similar results were obtained when the opening of mPTP was assessed by calcein AM assay using laser scanning microscopy or flow cytometry (Figure 5A, C). The fluorescence intensity of calcein was higher (indicating mPTP opening was inhibited) in rapamycin-treated cells than in vehicle-treated cells when A/R was persisted for 6 h/4 h, but no significant difference was noticed when A/R was prolonged to 24 h/4 h (Figure 5B, D). Treatment with wortmannin or silencing of beclin-1 did not change the fluorescence intensity of calcein (Figure 5B, D).

Figure 5.

Influence of different A/R injury on the opening of mPTP. (A) Representative pictures of calcein fluorescence detected with flow cytometry (first line) and laser confocal microscopy (second line) as well as JC-1 fluorescence (reflecting the depolarization of mitochondria) detected by laser confocal microscopy (third line). (B) Representative pictures of calcein fluorescence in response to pharmacological or genetic manipulation of autophagy. (C) Quantitative analysis of fluorescent intensity in the mitochondria of cardiomyocytes as shown in A. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.01 (anova) versus normoxia group. (D) Quantitative analysis of calcein fluorescent intensity in the mitochondria of cardiomyocytes as shown in B. *P < 0.05 versus DMSO group with the same A/R insult. n = 6 in each group of calcein flow cytometer assay, calcein confocal and JC-1 analysis respectively. Rap, rapamycin; Wor, wortmannin; N, normoxia.

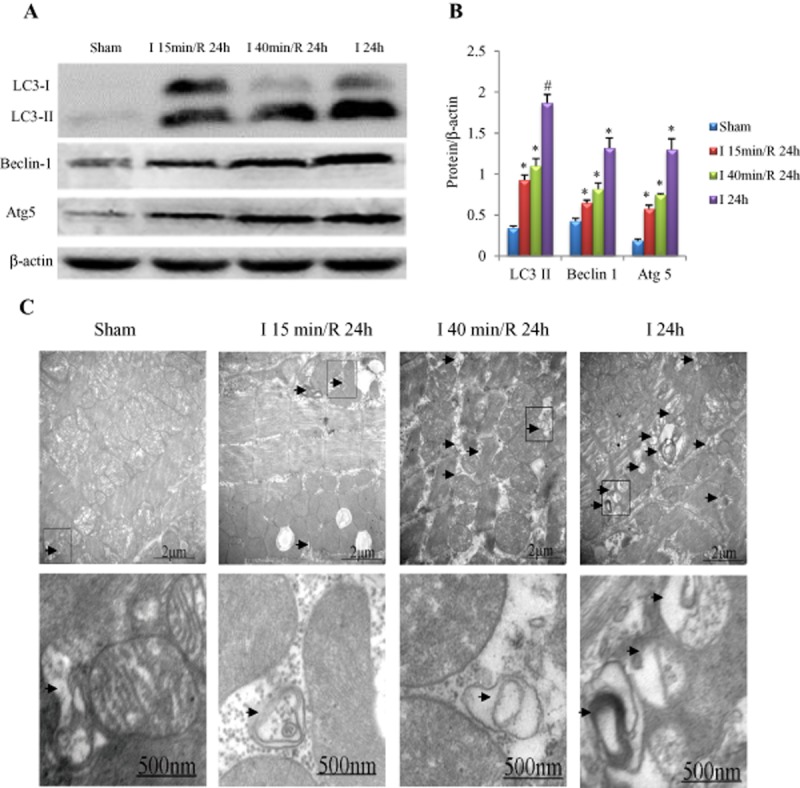

Autophagy triggered by I/R in the heart

In mice subjected to MI or I/R, the activity of autophagy was assessed by Western blot and electronic microscopy. We found that the expression levels of LC3-II, beclin1 and Atg5 proteins were significantly increased in mice that underwent ischaemia for 15 min and reperfusion for 24 h, and the proteins were further augmented when I/R was prolonged to 40 min/24 h, and reached a peak when the heart was subjected to ischaemia for 24 h (Figure 6A, B). The number of autophagosomes detected with electronic microscopy was also increased in an ischaemia duration-dependent manner (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Influence of ischaemia duration on myocardial autophagy. (A) Examples of Western blotting picture of autophagy-related proteins. (B) Quantitative analysis of LC3-II, beclin-1 and Atg5. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.01 versus sham, n = 5 in each group. (C) Electronic microscope findings. Autophagic vesicles (arrow) increased in an ischaemia duration-dependent manner (the magnified autophagic vesicles are shown in the second line).

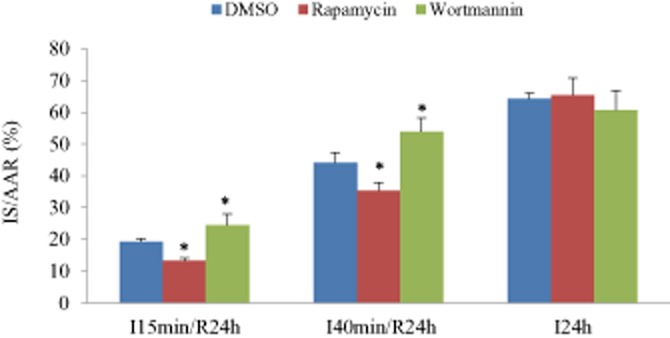

Influence of pharmaceutical manipulation of autophagy on myocardial infarct size

To further examine the role of autophagy in the ischaemic or I/R heart, mice were injected with rapamycin or wortmannin i.p. 60 min before MI or I/R. The myocardial infarct size was enlarged significantly in an ischaemia duration-dependent manner (Figure 7). Rapamycin reduced the infarct size when I/R persisted for 15 min/24 h and 40 min/24 h, but this effect disappeared when ischaemia was prolonged to 24 h (Figure 7). In contrast, for hearts that underwent 15 and 40 min of ischaemia, pretreatment with wortmannin significantly enlarged the infarct size; when the duration of ischaemia was extended to 24 h, the infarct size in the wortmannin-treated group was not enlarged (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Influence of ischaemia duration on myocardial injury. Myocardial infarct size (IS) was reduced by rapamycin (0.25 mg·kg−1) and increased by wortmannin (0.6 mg·kg−1) when ischaemia duration persisted for 15 or 40 min, but this effect disappeared when the ischaemia duration was extended to 24 h. For both (A and B), *P < 0.05 versus the responding control group (DMSO), n = 8 in each group.

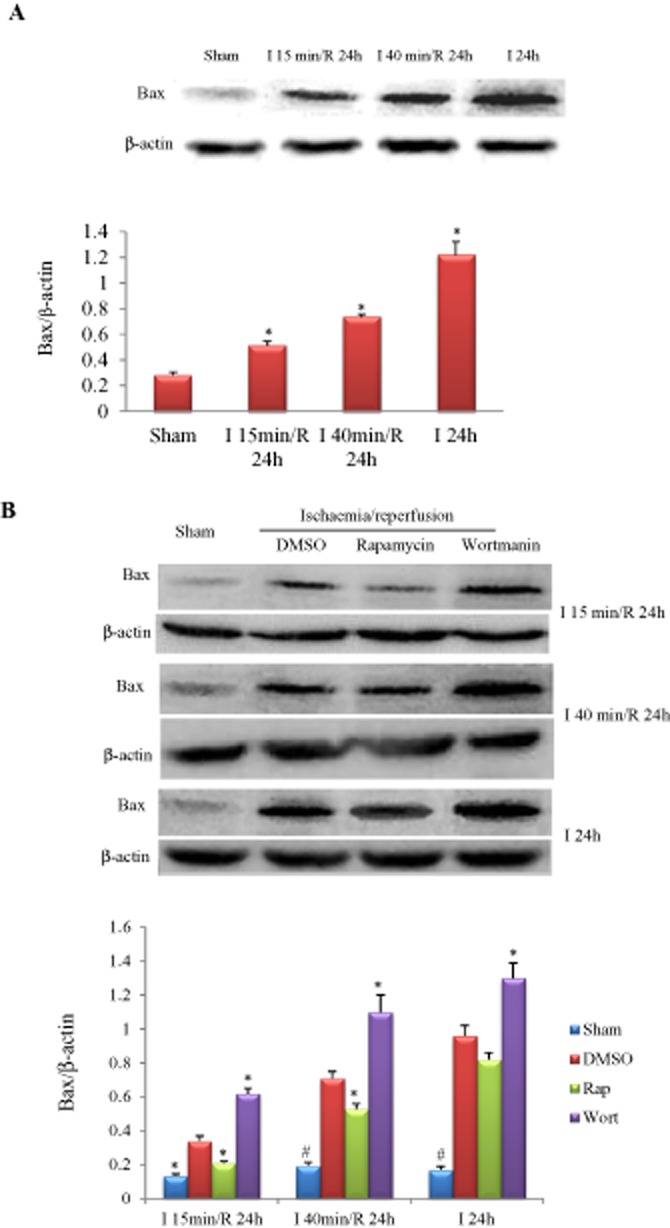

Effect of manipulating autophagy on the apoptotic protein Bax

The protein levels of Bax in the hearts of mice were increased in an ischaemia duration-dependent manner (Figure 8A). The up-regulation of Bax induced by myocardial ischaemia or IR was suppressed by rapamycin and enhanced by wortmannin (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Influence of ischaemia duration and autophagy manipulation on Bax expression. (A) Bax was increased in an ischaemia duration-dependent manner. *P < 0.05 versus sham, n = 5 in each group. (B) Effects of rapamycin (0.25 mg·kg−1) or wortmannin (0.6 mg·kg−1) on myocardial Bax expression in mice subjected to different durations of I/R injury. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.01 versus the corresponding DMSO-treated group, n = 5 in each group.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the distinct roles of autophagy in cardiomyocytes exposed to various degrees of I/R or A/R injury and found that (a) autophagic activity of cardiomyocytes was increased in an ischaemic or anoxia duration-dependent manner; (b) autophagy was beneficial for cells subjected to mild to moderate ischaemia or anoxia, but it was detrimental for cells exposed to severe ischaemia or anoxia; (c) excessive autophagic activity induced by severe anoxia or ischaemia was associated with an increase in autophagic cell death, in which case the autophagic inhibitor wortmannin was cardioprotective; (d) rapamycin-enhanced autophagic activity prevented the opening of mPTP in cells subjected to mild but not severe anoxia or ischaemia.

It is still unclear whether prolonged ischaemia is associated with increased autophagy activity. Although autophagy is reported to be inhibited during ischaemia but enhanced during reperfusion in HL-1 myocytes (Hamacher-Brady et al., 2007), most studies have found that myocardial autophagy in rodent animals is increased in response to I/R injury (Yan et al., 2005; Dosenko et al., 2006; Hamacher-Brady et al., 2006; 2007,; Matsui et al., 2007), while autophagy in cardiomyocytes is also increased in response to hypoxia alone or hypoxia followed by re-oxygenation (Zhang et al., 2012). In this study, we simulated ischaemia stimulation by subjecting cardiomyocytes or the murine heart to different durations of anoxia or ischaemia. We found that the prolonged anoxia/ischaemia duration was associated with an increase in autophagy and autophagic flux in cardiomyocytes or myocardium, while lysosomal inhibitors increased the expression of LC3-II and promoted apoptosis in anoxic cardiomyocytes, indicating that the autophagic activity is associated with the level of myocardial injury and inhibition of autophagic flux is harmful. These findings are in agreement with previous reports showing that autophagic flux is increased in hearts subjected to short- or long-time ischaemia, and enhancing autophagic flux is beneficial (Hsu et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2014). Beclin1 and Atg5 are members of the classical autophagy pathway and essential for autophagosome formation (Gustafsson and Gottlieb, 2009). In this study, we noted that both beclin1 and Atg5 proteins were increased in ischaemic hearts or anoxic cardiomyocytes, indicating that anoxia or ischaemia alone is sufficient to enhance autophagic activity.

Many studies support the notion that the enhancement of autophagy is cardioprotective (Yan et al., 2005; Hamacher-Brady et al., 2006); at the same time, there are also studies stating that autophagy will increase myocardial injury (Valentim et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2007; Gustafsson and Gottlieb, 2009). Therefore, opinions vary on the function of autophagy in myocardial injury. From the myocardial toxicity induced by adriamycin or sunitinib, other studies have concluded that autophagy is harmful (Lu et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2010). As for myocardial ischaemia, there are reports that the increase in autophagy is beneficial (Hamacher-Brady et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009; Maejima et al., 2013), but it has also been shown that an increase in autophagy is harmful (Cao et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013). In this study, we controlled the autophagic activity in cells by using its enhancer or inhibitor, and observed its protective or damaging effect. Although it has been reported that genes targeting the pathway of autophagosome formation could change the autophagic activity, it seems difficult to adjust the autophagic level accurately by using gain-and loss-of-function approaches. An enhancer or inhibitor of autophagy should be a proper pharmaceutical approach to adjust the autophagic activity by changing the dosage and administration time windows. Our findings in this study indicate that an enhancement of autophagy is beneficial for hearts or cardiomyocytes subjected to mild to moderate anoxia or ischaemia, while excessive autophagy is detrimental for cardiomyocytes subjected to prolonged ischaemia or anoxia. In the early periods of myocardial ischaemia or anoxia, the autophagy enhancer could inhibit cell apoptosis, thus showing cardioprotection. In contrast, when autophagic death increased in the late time windows of myocardial ischaemia or anoxia, the autophagy inhibitor could protect the myocardium. In the cell experiments in the present study, approximately 40% of the cells survived after 24 h of anoxia. We noted that wortmannin exerted its protective effect by inhibiting excessive autophagy; while in mice subjected to 24 h of myocardial ischaemia, wortmannin could not further reduce the infarct size, which might be attributable to the fact that the drug could not transfer into the ischaemic area after the infarction had occurred.

The relationship between autophagy and apoptosis is complicated. Autophagy not only inhibits apoptosis (Yan et al., 2005; Nishida et al., 2008; Long et al., 2013), but also accelerates apoptosis (Xu et al., 2013). In this study, we found that the cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by A/R increased when the duration was prolonged. At 6 h anoxia/4 h re-oxygenation, rapamycin did slightly, increase autophagic cell death (Figure 4B), but it largely inhibited cell apoptosis (Figure 3D), and consequently resulted in a net effect of promoting cell survival (Figure 2E), while wortmannin accelerated cell apoptosis, indicating that autophagy enhancer could exert cardioprotection through inhibiting cell apoptosis. However, when the duration of anoxia was prolonged to 24 h, both autophagic death and apoptosis were significantly increased, and rapamycin no longer improved cell survival, while wortmannin increased survival by inhibiting excessive autophagic death, which may also serve as an interpretation for our in vivo study showing that the protein Bax is increased in hearts of mice in an ischaemia duration-dependent manner; a phenomenon modulated in an opposite manner by wortmannin and rapamycin (Figure 8B). However, no significant difference in myocardial size was noted between the wortmannin- and rapamycin-treated groups when ischaemia prolonged to 24 h (Figure 7). In addition, considering that autophagy inhibits apoptosis, as demonstrated by previous reports (Yan et al., 2005; Nishida et al., 2008; Long et al., 2013), it is reasonable that wortmannin promotes cell apoptosis, while rapamycin inhibits apoptosis. It was reported that the incidence of autophagic cell death in the failing heart was higher than that of apoptosis (Martinet et al., 2007), suggesting that autophagy plays an important role in the outcome of heart failure. Our findings in this study indicate that whether autophagy is beneficial or detrimental depends on the overall effect of autophagic cell death and apoptosis.

Mitochondrial function is closely associated with autophagy and apoptosis. It was reported that the early and late autophagosomal markers Atg5 and LC3, respectively, are localized as puncta on mitochondria in mammalian cells during nutrient deprivation (Hailey et al., 2010). In mammals, Beclin1 localizes to mitochondria. In this study, we found that the increased protein expression levels of Atg5, LC3 and Beclin1, as well as the opening of mPTP, were dependent upon the duration of anoxia or ischaemia. Mitophagy is a surveillance mechanism of mitochondria. Yeast cells lacking core ATG genes have been shown to exhibit reduced mitochondrial activity, a reduced Δψm, and increased mtDNA instability (Zhang et al., 2007). However, autophagy is also reported to mediate about a 70% reduction in mitochondrial number in cells subjected to 3.5 h of starvation (Carreira et al., 2010). In the present study, we found that autophagy was beneficial for the maintenance of mitochondria function during mild anoxia, whereas autophagy plays a more complex role during severe anoxia since increasing or reducing autophagic activity did not affect the opening of mPTP, as measured by calcein staining.

In summary, the findings of this study indicate that the cardioprotection of autophagy induced by I/R is context-dependent, and therapies used to manipulate autophagy should be determined according to the time phase of I/R. The clinical significance of this study is that by using an autophagy enhancer in the early period of I/R, the myocardial injury could be lowered in patients with acute myocardial infarction on whom revascularization has been completed in time. However, for the patients with severe myocardial ischaemia but without vascular obstruction, using an autophagy inhibitor in the late period could improve myocardial survival. Since rapamycin has been used for the clinical treatment of organ transplantation rejection, the results of this study on whether it has curative effect in treating myocardial I/R injury are particularly relevant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81170146, to Y.L.).

Glossary

- A/R

anoxia/reoxygenation

- I/R

ischaemia/reperfusion

- JC-1

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide

- MDC

monodansylcadaverine

- mPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- NRCs

neonatal rat cardiomyocytes

- sh

short hairpin

- TTC

triphenyltetrazolium chloride

Author contributions

Y. Li., Qi. X., J. B. conceived and designed the study; Q. X., Y. L., J. B., J. Z., S. C., X. H. analysed and interpreted the results; Q. X., X. L., Y. L., L. S. performed the experiments and collected the data; Y. L., Q. X., J. Z. drafted, edited and revised the paper before submission; and all authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Aki T, Yamaguchi K, Fujimiya T, Mizukami Y. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase accelerates autophagic cell death during glucose deprivation in the rat cardiomyocyte-derived cell line H9c2. Oncogene. 2003;22:8529–8535. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Sheiko T, Craigen WJ, Molkentin JD. Voltage-dependent anion channels are dispensable for mitochondrial-dependent cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:550–555. doi: 10.1038/ncb1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Chen A, Yang P, Song X, Liu Y, Li Z, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury by inhibiting autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;441:935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.10.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira RS, Lee Y, Ghochani M, Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Cyclophilin D is required for mitochondrial removal by autophagy in cardiac cells. Autophagy. 2010;6:462–472. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.4.11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Mekkaoui C, Cho H, Ngoy S, Marinelli B, Waterman P, et al. Fluorescence tomography of rapamycin-induced autophagy and cardioprotection in vivo. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:441–447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenko VE, Nagibin VS, Tumanovska LV, Moibenko AA. Protective effect of autophagy in anoxia-reoxygenation of isolated cardiomyocyte? Autophagy. 2006;2:305–306. doi: 10.4161/auto.2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi M, Sukhodub A, Jovanovic S, Jovanovic A. Mg2+ protects adult beating cardiomyocytes against ischaemia. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:69–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujio Y, Nguyen T, Wencker D, Kitsis RN, Walsh K. Akt promotes survival of cardiomyocytes in vitro and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse heart. Circulation. 2000;101:660–667. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami S, Eshragi M, Ande SR, Chazin WJ, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ, et al. S100A8/A9 induces autophagy and apoptosis via ROS-mediated cross-talk between mitochondria and lysosomes that involves BNIP3. Cell Res. 2010;20:314–331. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Autophagy in ischemic heart disease. Circ Res. 2009;104:150–158. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK, et al. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Gottlieb RA. Enhancing macroautophagy protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29776–29787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Logue SE, Sayen MR, Jinno M, Kirshenbaum LA, et al. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:146–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Cha J, Yoshie M, Daikoku T, Dey SK. Heightened uterine mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling provokes preterm birth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18073–18078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108180108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CP, Oka S, Shao D, Hariharan N, Sadoshima J. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates cell survival through NAD+ synthesis in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009;105:481–491. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg JS, Klaunig JE. Role of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition (MPT) in rotenone-induced apoptosis in liver cells. Toxicol Sci. 2000;53:340–351. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/53.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori H, Takemura G, Goto K, Maruyama R, Ono K, Nagao K, et al. Autophagy limits acute myocardial infarction induced by permanent coronary artery occlusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H2261–H2271. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01056.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG Group NCRRGW. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Xu X, Chen K, Liang Q. Suppression of autophagy is protective in high glucose-induced cardiomyocyte injury. Autophagy. 2012;8:577–592. doi: 10.4161/auto.18980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Asakura M, Takashima S, Ogai A, Asano Y, Asanuma H, et al. Benidipine, a long-acting calcium channel blocker, inhibits cardiac remodeling in pressure-overloaded mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Yang X, Southwood M, Lu J, Marciniak SJ, Dunmore BJ, et al. Chloroquine prevents progression of experimental pulmonary hypertension via inhibition of autophagy and lysosomal bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor degradation. Circ Res. 2013;112:1159–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Wu W, Yan J, Li X, Yu H, Yu X. Adriamycin-induced autophagic cardiomyocyte death plays a pathogenic role in a rat model of heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T, Chen B, Zhao Z, He N, Zeng Z, Wu B, et al. Histamine H2 receptor activation exacerbates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by disturbing mitochondrial and endothelial function. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:342–356. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima Y, Kyoi S, Zhai P, Liu T, Li H, Ivessa A, et al. Mst1 inhibits autophagy by promoting the interaction between Beclin1 and Bcl-2. Nat Med. 2013;19:1478–1488. doi: 10.1038/nm.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinet W, Knaapen MW, Kockx MM, De Meyer GR. Autophagy in cardiovascular disease. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Takagi H, Qu X, Abdellatif M, Sakoda H, Asano T, et al. Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ Res. 2007;100:914–922. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261924.76669.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SS, Tsao MS, Nicklee T, Hedley DW. Wortmannin inhibits pkb/akt phosphorylation and promotes gemcitabine antitumor activity in orthotopic human pancreatic cancer xenografts in immunodeficient mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3269–3275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida K, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K. Crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in heart disease. Circ Res. 2008;103:343–351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CN, Kyoi S, Hariharan N, Takagi H, Sadoshima J, Gottlieb RA. Novel methods for measuring cardiac autophagy in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 2009;453:325–342. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04016-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciarretta S, Hariharan N, Monden Y, Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. Is autophagy in response to ischemia and reperfusion protective or detrimental for the heart? Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;32:275–281. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9855-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentim L, Laurence KM, Townsend PA, Carroll CJ, Soond S, Scarabelli TM, et al. Urocortin inhibits Beclin1-mediated autophagic cell death in cardiac myocytes exposed to ischaemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.03.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanrell MC, Cueto JA, Barclay JJ, Carrillo C, Colombo MI, Gottlieb RA, et al. Polyamine depletion inhibits the autophagic response modulating Trypanosoma cruzi infectivity. Autophagy. 2013;9:1080–1093. doi: 10.4161/auto.24709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Kobayashi S, Chen K, Timm D, Volden P, Huang Y, et al. Diminished autophagy limits cardiac injury in mouse models of type 1 diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:18077–18092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.474650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan W, Wu B, Chen C, Chen B, Zhang W, Xu D, et al. Resveratrol improves myocardial ischemia and ischemic heart failure in mice by antagonizing the detrimental effects of fractalkine*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3026–3033. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825fd7da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Vatner DE, Kim SJ, Ge H, Masurekar M, Massover WH, et al. Autophagy in chronically ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13807–13812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506843102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano H, Nakanishi S, Kimura K, Hanai N, Saitoh Y, Fukui Y, et al. Inhibition of histamine secretion by wortmannin through the blockade of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in RBL-2H3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25846–25856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Shen L, Li X, Luo T, Wei X, Zhang J, et al. Disruption of histamine H2 receptor slows heart failure progression through reducing myocardial apoptosis and fibrosis. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014;127:435–448. doi: 10.1042/CS20130716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JL, Lu JK, Chen D, Cai Q, Li TX, Wu LS, et al. Myocardial autophagy variation during acute myocardial infarction in rats: the effects of carvedilol. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:2372–2379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Qi H, Taylor R, Xu W, Liu LF, Jin S. The role of autophagy in mitochondria maintenance: characterization of mitochondrial functions in autophagy-deficient S. cerevisiae strains. Autophagy. 2007;3:337–346. doi: 10.4161/auto.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YL, Yao YT, Fang NX, Zhou CH, Gong JS, Li LH. Restoration of autophagic flux in myocardial tissues is required for cardioprotection of sevoflurane postconditioning in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014;35:758–769. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZL, Fan Y, Liu ML. Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits autophagy in H9c2 cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;365:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Wang S, Wang Z, Sun A, Yang X, Qiu Z, et al. CXCR6 deficiency ameliorated myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting infiltration of monocytes and IFN-gamma-dependent autophagy. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:853–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Xue T, Yang X, Zhu H, Ding X, Lou L, et al. Autophagy plays an important role in sunitinib-mediated cell death in H9c2 cardiac muscle cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;248:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Tannous P, Johnstone JL, Kong Y, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, et al. Cardiac autophagy is a maladaptive response to hemodynamic stress. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1782–1793. doi: 10.1172/JCI27523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]