Abstract

Objectives

There are a number of potential advantages to performing hysteroscopy in an outpatient setting. However, the ideal approach, using local uterine anesthesia or rectal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, has not been determined. Our objective was to compare the efficacy of intrauterine lidocaine instillation with rectal diclofenac for pain relief during diagnostic hysteroscopy.

Methods

We conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial on 70 nulliparous women with primary infertility undergoing diagnostic hysteroscopy. Subjects were assigned into one of two groups to receive either 100mg of rectal diclofenac or 5mL of 2% intrauterine lidocaine. The intensity of pain was measured by a numeric rating scale 0–10. Pain scoring was performed during insertion of the hysteroscope, during visualization of the intrauterine cavity, and during extrusion of the hysteroscope.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups with regard to the mean pain score during intrauterine visualization (p=0.500). The mean pain score was significantly lower during insertion and extrusion of the hysteroscope in the diclofenac group (p=0.001 and p=0.030, respectively). Nine patients in the lidocaine group and five patients in diclofenac group needed supplementary intravenous propofol injection for sedation (p=0.060).

Conclusions

Rectal diclofenac appears to be more effective than intrauterine lidocaine in reducing pain during insertion and extrusion of hysteroscope, but there are no significant statistical and clinical differences between the two methods with regard to the mean pain score during intrauterine inspection.

Keywords: Diclofenac, Hysteroscopy, Lidocaine, Pain, Pain Measurement

Introduction

Hysteroscopy is a safe and feasible procedure for diagnosing intrauterine pathology, including abnormal uterine bleeding, infertility, and recurrent pregnancy loss, and is essential for the performance of many minimally invasive intrauterine therapeutic interventions.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy can be performed in an outpatient setting, which has the benefit of increased safety, reduced utilization of resources, and improved patient satisfaction. Although the procedure is well tolerated, most patients experience pain. To alleviate this, various methods of systemic analgesia including opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthesia have been advocated.1-20

Intrauterine instillation of topical anesthetic is easy, relatively painless, and promising as an adequate analgesia during diagnostic hysteroscopy. This technique could be the ideal anesthesia for infertile women undergoing outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy. Meta-analysis revealed a beneficial effect of local anesthetics versus placebo or no treatment during and within 30 minutes after hysteroscopy. However, there was no evidence of benefit for the use of local anesthetics or oral analgesics compared to placebo or no treatment for pain relief more than 30 minutes after a hysteroscopy. The use of intravenous sedation compared to paracervical block demonstrated a significant reduction in the mean pain score more than 30 minutes after the procedure, but not during or within 30 minutes of the procedure.8

One randomized controlled trial, including 120 participants divided into three groups, demonstrated a significant reduction in the mean pain score during hysteroscopy with the use of oral drotaverine hydrochloride and mefenamic acid when compared to the paracervical block and intravenous sedation with diazepam group.9

Since rectal NSAIDs act more rapidly than the oral form and there was no study for rectal use of these drugs for hysteroscopy, we sought to compare the efficacy of intrauterine lidocaine instillation with rectal diclofenac for pain relief in infertile women undergoing diagnostic hysteroscopy.

Methods

This randomized, double-blind clinical trial was approved by the Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The study was performed at the Center of Reproductive Medicine, Dr.Shariati Hospital, from July 2012 to April 2013. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Ninety-four ASA physical status I-II (American Society of Anesthesiologist’s classification for risk of anesthesia according to underlying diseases) nulliparous women with primary infertility aged 18–40 years old and scheduled for diagnostic hysteroscopy were randomly allocated into one of two groups: intrauterine lidocaine instillation or rectal diclofenac. Patients with known cervical stenosis, respiratory or cardiac dysfunction, a previous adverse reaction to any of the drugs used in the study, or an inability to understand how to score the pain, and patients who needed invasive intrauterine therapeutic interventions during the hysteroscopy (such as endometrial biopsy, uterine adhesiolysis, myomectomy, or polypectomy) were excluded. If the patient could not tolerate the procedure, 15µg/kg of propofol was injected intravenously and the patient was also excluded from the study.

Randomization was performed using computer generated codes. Sealed envelopes containing the information of the randomization code were kept by the staff not involved in the study. The envelope was transferred to a specific member of the gynecologic staff. In the gynecologic ward, 30 minutes before transferring to the operating room, the staff gave 100mg rectal diclofenac to patients in the diclofenac group. The envelope was sealed again and kept in the patient’s folder until the end of the study. All members of the surgical team, nursing staff, patients, and the anesthetist were unaware of the allocation.

After arrival in the operating room, standard monitoring, including electrocardiogram, arterial oxygen saturation, and noninvasive blood pressure were connected to the patients. A 20-gauge IV cannula was inserted for each patient and 3ml/kg ringer lactate solution was infused. Before surgery, patients were educated about the numeric rating scale (NRS) in which 0 indicated no pain and 10 the worst pain imaginable.

All patients were put in the lithotomy position and a sterile bivalve speculum was introduced into the vagina for visualization of the cervix. The cervix and vagina were washed with antiseptic solution. The cervix was grasped with single-toothed tenaculum after anesthetizing the grasping site with 1ml of 2% lidocaine to straighten the uterine axis. The study drugs (lidocaine or saline) were prepared by the anesthesia staff who gave it to the surgeon who was blinded to allocation. Then 5ml of 2% lidocaine or the same volume of saline was instilled through the endocervix into the uterine cavity with an 18-gauge angiocatheter. The angiocatheter was left in place for three minutes before it was withdrawn while patients were in the Trendelenburg position to limit backflow and to allow the anesthetic to take effect. A rigid 3.5mm hysteroscope was used for hysteroscopy by the surgeon. Pain scores were evaluated on three separate occasion: during insertion of the hysteroscope, during visualization of uterine cavity, and during extrusion of the hysteroscope.

Patients data including age, weight, duration of hysteroscopy, and pain scores were all recorded and compared between the study groups.

Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and chi-square test were used where appropriate. According to a previous study, the incidence of pain in the local anesthesia group was 40%. In order to detect a difference of 30% for pain on the NRS, with two-sided alpha levels of 0.05 and a power of 80%, the estimated sample size was calculated as 35 participants in each group.

Results

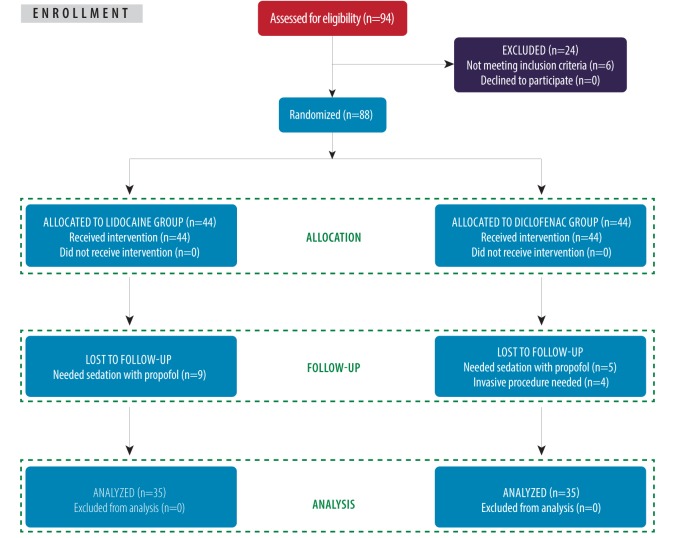

A total of 94 consecutive patients were evaluated for eligibility and 24 patients were excluded, of which six patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, 14 needed supplementary propofol for sedation and four needed invasive intrauterine therapeutic interventions during hysteroscopy [Figure1].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study showing the allocation and follow-up of the two groups.

Demographic data and duration of the hysteroscopy were not statistically different in the study groups [Table1].

Table 1. Demographic data and duration of hysteroscopy in the study groups.

| Variable | Lidocaine group (n=35) | Diclofenac group (n=35) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.3±4.4 | 30.8±4.4 | 0.060 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.8±8.3 | 67.3±9.3 | 0.050 |

| ASA class I/II (n) | 31/4 | 28/7 | 0.120 |

| Duration of hysteroscopy (minutes) | 13.4±3.5 | 13.7±3.9 | 0.140 |

Data presented as mean ±SD.

There were no statistically significant differences between the study group of patients with regard to the mean pain score during visualization of uterine cavity (p=0.500). The mean pain score was significantly lower during insertion and extrusion of the hysteroscope in the diclofenac group (p=0.001 and p=0.030, respectively) [Table 2].

Table 2. Mean pain scores for individual steps of hysteroscopy in the study groups.

| Step of the procedure | Lidocaine group | Diclofenac group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insertion of hysteroscope | 2.1±1.2 | 0.8±1.1 | 0.001 |

| Inspection of uterine cavity | 2.4±1.1 | 2.1±1.3 | 0.500 |

| Extrusion of hysteroscope | 1.1±1.7 | 0.7±1.0 | 0.030 |

Data presented as mean ±SD.

Nine patients in the lidocaine group and five patients in the diclofenac group needed an intravenous propofol injection (p=0.060).

Discussion

Our study showed that rectal diclofenac sodium was more effective than intrauterine lidocaine instillation at reducing pain during insertion and extrusion of a hysteroscope, but there was no significant statistical and clinical difference between the two methods with regard to the mean pain scores during intrauterine inspection.

There are several causes of pain during and after hysteroscopy. During hysteroscopy, the first cause of pain is usually cervical manipulation. The cervix is often grasped with an instrument, such as a tenaculum, and may be cannulated and dilated to allow the hysteroscope to pass through. Pain stimuli from the cervix and vagina are conducted by visceral afferent fibers to the spinal ganglia (S2 to S4) via the pudendal and pelvic splanchnic nerves, along with parasympathetic fibers. Following cervical manipulation, cannulation, and dilatation, distention of the uterus during hysteroscopy can also cause pain. Delayed pain may be caused by the release of prostaglandins due to the cervical manipulation as well as distension of the uterus.10-18

In a randomized trial by Lau et al,3 on 90 women undergoing hysteroscopy with or without endometrial biopsy, instillation of 5mL of 2% lignocaine into the uterine cavity was not effective in decreasing hysteroscopy-related pain, which correlated with our study. However, in our study all of our patients were nulliparous and the majority of women in the Lau study were multiparous.

In another study by Sharma et al,9 on 120 women undergoing hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy, there was significant reduction in the mean pain score with the use of oral drotaverine hydrochloride and mefenamic acid compared to paracervical block and intravenous sedation using diazepam. Although they used oral NSAIDs plus drotaverine (a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4), their results correlated with ours.

Since additional pain can be caused by release of prostaglandins due to cervical manipulation, and distension of the uterus, further studies should be undertaken to estimate the efficacy of rectal NSAIDs with antiprostaglandin effects. These should be combined with other drugs for pain relief and the pain measured during and after the hysteroscopy.

Our study was limited by the small number of patients evaluated, the lack of a placebo controlled group, and lack of evaluation of other secondary outcome measures like heart rate and blood pressure. Since cultural factors also contribute to the pain tolerance levels, multicenter, placebo-controlled trials need to be conducted to prove the efficacy of rectal diclofenac or intrauterine lidocaine for outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy.

Conclusion

Rectal diclofenac appears to be more effective than intrauterine lidocaine in reducing pain during insertion and extrusion of a hysteroscope, but there are no significant statistical and clinical differences between the two methods with regard to the mean pain score during intrauterine inspection to support this finding.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interests. This research was supported by a Tehran University of Medical Sciences & Health Services grant.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the physicians, nurses and anesthesia staff for their cooperation.

References

- 1.Hassan L, Gannon MJ. Anaesthesia and analgesia for ambulatory hysteroscopic surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2005. Aug;19(5):681-691. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau WC, Lo WK, Tam WH, Yuen PM. Paracervical anaesthesia in outpatient hysteroscopy: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999. Apr;106(4):356-359. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau WC, Tam WH, Lo WK, Yuen PM. A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of transcervical intrauterine local anaesthesia in outpatient hysteroscopy. BJOG 2000. May;107(5):610-613. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giorda G, Scarabelli C, Franceschi S, Campagnutta E. Feasibility and pain control in outpatient hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women: a randomized trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000. Jul;79(7):593-597. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079007593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicinelli E, Didonna T, Ambrosi G, Schönauer LM, Fiore G, Matteo MG. Topical anaesthesia for diagnostic hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy in postmenopausal women: a randomised placebo-controlled double-blind study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997. Mar;104(3):316-319. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11460.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Downes E, al-Azzawi F. How well do perimenopausal patients accept outpatient hysteroscopy? Visual analogue scoring of acceptability and pain in 100 women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1993. Jan;48(1):37-41. 10.1016/0028-2243(93)90051-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broadbent JA, Hill NC, Molnár BG, Rolfe KJ, Magos AL. Randomized placebo controlled trial to assess the role of intracervical lignocaine in outpatient hysteroscopy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992. Sep;99(9):777-779. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabli N, Tulandi T. A randomized trial of outpatient hysteroscopy with and without intrauterine anesthesia. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2008. May-Jun;15(3):308-310. 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma JB, Aruna J, Kumar P, Roy KK, Malhotra N, Kumar S. Comparison of efficacy of oral drotaverine plus mefenamic acid with paracervical block and with intravenous sedation for pain relief during hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy. Indian J Med Sci 2009. Jun;63(6):244-252. 10.4103/0019-5359.53394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad G, O’Flynn H, Attarbashi S, Duffy JM, Watson A. Pain relief for outpatient hysteroscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(11):CD007710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barcaite E, Bartusevicius A, Railaite DR, Nadisauskiene R. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005. Nov;91(2):141-145. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preutthipan S, Herabutya Y. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before operative hysteroscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2000. Dec;96(6):890-894. 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01063-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Readman E, Maher PJ. Pain relief and outpatient hysteroscopy: a literature review. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2004. Aug;11(3):315-319. 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60042-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trolice MP, Fishburne C, Jr, McGrady S. Anesthetic efficacy of intrauterine lidocaine for endometrial biopsy: a randomized double-masked trial. Obstet Gynecol 2000. Mar;95(3):345-347. 10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00557-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui SK, Lee L, Ong C, Yu V, Ho LC. Intrauterine lignocaine as an anaesthetic during endometrial sampling: a randomised double-blind controlled trial. BJOG 2006. Jan;113(1):53-57. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campo V, Campo S. [Hysteroscopy requirements and complications]. Minerva Ginecol 2007. Aug;59(4):451-457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Sunaidi M, Tulandi T. A randomized trial comparing local intracervical and combined local and paracervical anesthesia in outpatient hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2007. Mar-Apr;14(2):153-155. 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zupi E, Luciano AA, Marconi D, Valli E, Patrizi G, Romanini C. The use of topical anesthesia in diagnostic hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1994. May;1(3):249-252. 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)81018-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shukri M, Al-Ghafri W, Gowri V. Pelvic nodules in a gynecologic patient. Oman Med J 2013. Jul;28(4):292-293. 10.5001/omj.2013.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathew M, Mohan AK. Recurrent cervical stenosis - a troublesome clinical entity. Oman Med J 2008. Jul;23(3):195-196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]