Performed in wide range of patients, from teenagers to women in their sixties and beyond, bilateral breast augmentation has become one of the most common procedures in aesthetic plastic surgery. Capsular contracture represents one of the most frequent complications of the procedure, typically occurring one year postoperatively. Although several risk factors for the development of capsular fibrosis, such as infections, seroma and type of implant, among others, have been identified, age at primary augmentation has received less attention. Accordingly, this retrospective case study investigated the influence of age at primary augmentation in 43 patients who presented for surgical revision of capsular contracture.

Keywords: Augmentation mammoplasty, Capsular contracture, Patient age

Abstract

The influence of age on capsular contracture rates remains unclear. Most studies have only investigated early capsule development and not whether a link between age at primary surgery and the later development of capsular fibrosis exists. To clarify whether patient age impacts the development of late capsular fibrosis, the authors conducted a retrospective case study involving 43 patients who presented for surgical revision of capsular contracture (Baker grade ≥III) between four and 40 years after primary breast augmentation. Possible correlations between age and implant placement were analyzed. Late presentation of capsular fibrosis occurred a mean of 15.6 years after primary augmentation, with a slightly negative, but not significant, correlation between age at primary operation and duration of implant placement. Patients <40 years of age underwent an operative revision after a mean of 18.9 years, while patients ≥40 years of age needed an operative revision a mean of 11.9 years after primary breast augmentation (P=0.0368). The results suggest that with advancing age, the average time to develop capsular fibrosis is significantly shorter in individuals who develop capsular contracture. As more data are collected, appropriate advice can be provided to patients regarding factors that influence the long-term outcomes of breast augmentation.

Abstract

On ne connaît pas l’influence de l’âge sur le taux de contractures capsulaires. La plupart des études portent seulement sur l’apparition précoce de capsules et n’abordent pas la possibilité d’un lien entre l’âge au moment de la chirurgie primaire et l’apparition ultérieure de fibrose capsulaire. Pour établir si l’âge des patientes influe sur l’apparition de fibrose capsulaire tardive, les auteurs ont réalisé une étude rétrospective auprès de 43 patientes qui ont demandé une révision chirurgicale de la contracture capsulaire (grade ≥ III selon l’échelle de Baker) de quatre à 40 ans après l’augmentation mammaire primaire. Ils ont analysé les corrélations possibles entre l’âge et la pose des implants. La présentation tardive de la fibrose capsulaire se produisait en moyenne 15,6 ans après l’augmentation primaire, et la corrélation était légèrement négative, mais non significative, entre l’âge au moment de l’opération primaire et la durée de mise en place des implants. Les patientes de moins de 40 ans subissaient une révision opératoire au bout d’une moyenne de 18,9 ans, tandis que celles de 40 ans ou plus s’y soumettaient en moyenne 11,9 ans après l’augmentation mammaire primaire (P=0,0368). Selon ces résultats, avec le vieillissement, le délai moyen d’apparition d’une fibrose capsulaire est considérablement plus court chez les personnes qui présentent une contracture capsulaire. L’accumulation de données permettra de mieux conseiller les patientes quant aux facteurs qui influent sur les résultats à long terme de l’augmentation mammaire.

Breast augmentation has become one of the most common procedures performed in aesthetic surgery in recent years. Previous studies have reported the mean patient age at surgery to be 33 years (range 15 to 66 years) (1,2). Capsular contraction has been reported to be the most common complication following primary aesthetic breast augmentation (3–5). Capsular contraction most commonly occurs within the first year postoperatively (6). There is a cumulative risk for developing capsular fibrosis, which increases with time after implant placement (6,7). Certain risk factors, such as infections, hematoma, seroma, and the composition and texture of the implants, have been implicated in the development and degree of capsular fibrosis (1,8–10). Other proposed risk factors include operative technique, pocket choice and patient characteristics (alcohol abuse, smoking and obesity) (11–13). Little has been published on the influence of age on capsular contracture rates after the first year following surgery. Patient age at primary augmentation has not been shown to influence the early postoperative complication rate, including the development of capsular fibrosis. Most studies have only investigated early capsule development and not whether a link between age at primary surgery and the later development of capsular fibrosis exists (14). To clarify whether patient age impacts the long-term development of capsular fibrosis, we conducted a retrospective case study involving 43 patients who presented for surgical revision of capsular contracture between four and 40 years after primary breast augmentation.

METHODS

In the current retrospective study, all patients who presented between 2003 and 2012 for an operative revision due to capsular contracture Baker grade ≥III (15) ≥4 years after primary breast augmentation were included. Patients who were surgically treated for implant rupture, infections or displacement were not included in the present study. Patient age at the primary operation and age at the secondary surgery and the duration of implant placement were analyzed. The correlation between age and implant placement was calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient ρ, with ρ>0.5 indicating a strong correlation. To perform statistical analysis, the patients were divided into age groups (<20 to 29, 30 to 39 and ≥40 years of age); these groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (<30 versus ≥30 and <40 versus ≥40 years of age).

RESULTS

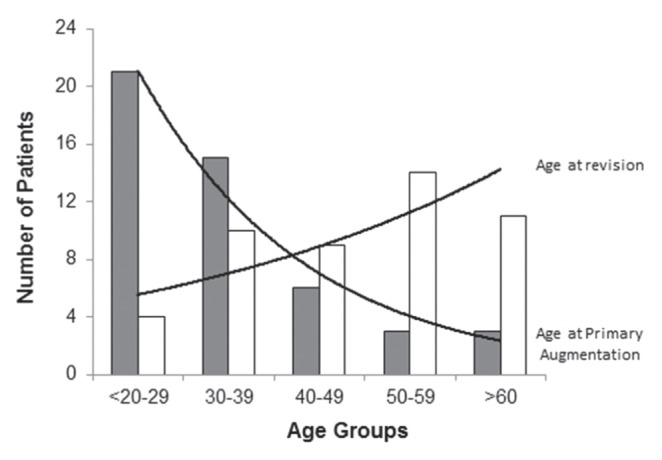

During the examination period, 43 patients presented for surgical revision due to a contracture (Baker grade ≥III) after primary aesthetic breast augmentation. A bilateral revision was performed in all cases. The mean age at the primary operation was 34.16 years (range 17 to 69 years) and 49.8 years (range 22 to 74 years) at operative revision (Figure 1). In the present study, late presentation of capsular contracture occurred a mean (± SD) of 15.6±10.4 years after primary augmentation (range four to 37 years). The study found a slightly negative, but not significant (P=0.12), correlation between age at primary operation and duration of implant placement (ρ=−0.23). When the duration of implantation between age groups presenting for secondary revision was examined, patients <30 years of age (n=17) underwent an operative revision at a mean of 18.54±10.97 years (range four to 37 years) after primary augmentation; patients ≥30 years of age (n=26) underwent an operative revision at a mean of 13.4±9.5 (range four to 30 years) after primary augmentation. This difference was not statistically significant (P>0.05).

Figure 1).

Age distribution at primary aesthetic breast augmentation (solid bars) and revision (white bars)

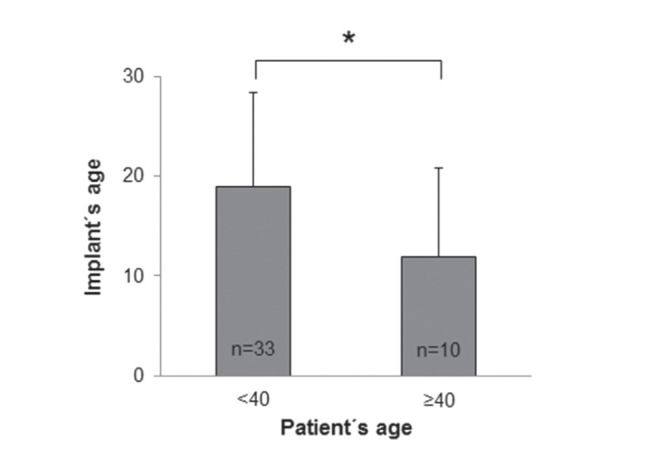

Patients <40 years of age (n=33) underwent an operative revision a mean of 18.9±9.5 years (range five to 37 years) after primary breast augmentation; however, patients ≥40 years of age (n=10) needed an operative revision a mean of 11.9±8.9 years (range four to 30 years) after primary breast augmentation (Figure 2). This difference was statistically significant (P=0.0368).

Figure 2).

Implant age (years) in patients <40 and ≥40 years of age. Data presented as mean ± SD; *P≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant

DISCUSSION

Bilateral breast augmentation has become one of the most common procedures performed in aesthetic surgery in recent years. Common reasons for revision include size change, asymmetry and malposition (1). Capsular contracture has been reported to be the most common complication. In two large reviews, Dancey et al (1) and Henriksen et al (2) reported capsular contraction (Baker >II) rates of 26.9% (n=1400) and 4.3% (n=2277), in which an operative revision was necessary in 7.9% (n=110) and 1.3% (n=29), respectively. Capsular contracture is believed to most likely occur within the first year of surgery. It has been a commonly held belief that after the first two years, contracture is unlikely to develop. However, there is a paucity of data to support this theory. Recent long-term studies indicate there may be a cumulative risk for the development of Baker III and IV capsules (16–18). Known risk factors, such as operative technique, hematoma (1,11), bacterial infections and biofilm development, especially with Staphylococcus epidermidis or Pseudomonas species, are most likely to impact early capsular development (19–22); however, very little is known about the factors that may influence the long-term cumulative risk. Marques et al (18) showed a cumulative risk of Baker III/IV capsules in long-term follow-up from 7% in the first two years to 10% over an eight-year period. They also found an increased risk for capsular contracture in women who underwent their primary surgery when they were >54 years of age. They investigated factors such as menopause or estrogen therapy and could find no evidence of a causal link. To determine whether age has an influence on the cumulative risk for capsular contracture, we performed a retrospective study involving 43 patients who presented for revisional surgery to correct symptomatic Baker III/IV capsules after primary breast augmentation surgery. Patients who presented within three years of primary augmentation surgery were excluded. There were very little data regarding the original surgery of these patients; therefore, no conclusions regarding the influence of early operative/postoperative factors were drawn. Our analysis of this cohort indicated a relationship, but not a causal context, between age at time of primary augmentation and later capsular contracture. Patients ≥40 years of age at the time of primary surgery presented for surgical revision of capsular contracture significantly sooner than those who underwent their surgery when they were <40 years of age. However, it remains unclear as to what degree capsular fibrosis is due to biogerontological factors (perimenopausal changes) or patients’ individual perception of risk behaviour and well-being, which impact the decision to undergo an operative revision. Regular breast cancer screening and medical check-ups in women ≥40 years of age could be a factor in the detection of capsular contraction requiring surgical revision (23,24).

CONCLUSION

The present study confirmed previous findings that patient age at primary augmentation does not influence the incidence of capsular contracture. Our results, however, suggest that in older patients who do develop capsular contracture, the average time to develop capsular fibrosis is significantly shorter. These findings would suggest a relationship between age and late development of capsular contracture. The reasons for this are not clear. Further studies investigating sociocultural and biogerontological factors are necessary. We acknowledge that the present study had significant limitations given its retrospective design and many unknown variables; therefore, few conclusions can be drawn. We can recommend that the long-term cumulative risk for capsular contracture warrants further study. Our findings indicate that there are several factors that influence the long-term development of capsular contracture that are different from the well-known factors that influence capsule development within the early postoperative period. With the development of breast implant registries, there is the potential for long-term outcome studies to further examine what has received little attention – that of the long-term cumulative risk of capsular contracture. As more data are collected, appropriate advice can be provided to patients regarding factors that influence the long-term outcomes of breast augmentation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dancey A, Nassimizadeh A, Levick P. Capsular contracture – what are the risk factors? A 14 year series of 1400 consecutive augmentations. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henriksen TF, Fryzek JP, Hölmich LR, et al. Surgical intervention and capsular contracture after breast augmentation: A prospective study of risk factors. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54:343–51. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000151459.07978.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Handel N, Cordray T, Gutierrez J, et al. A long-term study of outcomes, complications, and patient satisfaction with breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:757–67. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000201457.00772.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham B. The mentor core study on silicone memorygel breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(7 Suppl 1):19–32. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000286574.88752.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spear SL, Murphy DK, Slicton A, et al. Inamed Silicone Breast Implant U.S. Study Group. Inamed silicone breast implant core study results at 6 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(7 Suppl 1):8–18. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000286580.93214.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henriksen TF, Holmich LR, Fryzek JP, et al. Incidence and severity of short-term complications after breast augmentation: Results from a nationwide breast implant registry. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51:531–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000096446.44082.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrath MH, Burkhardt BR. The safety and efficacy of breast implants for augmentation mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:550–60. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198410000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittet B, Montandon D, Pittet D. Infection in breast implants. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:94–106. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreml S, Heine N, Eisenmann-Klein M, et al. Bacterial colonization is of major relevance for high-grade capsular contracture after augmentation mammaplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:126–30. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000252714.72161.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong CH, Samuel M, Tan BK, et al. Capsular contracture in subglandular breast augmentation with textured versus smooth breast implants: A systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:1224–36. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000237013.50283.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiener TC. Relationship of incision choice to capsular contracture. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:303–6. doi: 10.1007/s00266-007-9061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Embrey M, Adams EE, Cunningham B, et al. A review of the literature on the etiology of capsular contracture and a pilot study to determine the outcome of capsular contracture interventions. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999;23:197–206. doi: 10.1007/s002669900268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stock W, Wolf K. Capsule fibrosis in silicone implants. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1986;369:303–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01274377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens WG, Spring M, Stoker DA, et al. A review of 100 consecutive secondary augmentation/mastopexies. Aesthet Surg J. 2007;27:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spear SL, Baker JL., Jr Classification of capsular contracture after prosthetic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1119–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedén P, Boné B, Murphy DK, Slicton A, Walker PS. Style 410 cohesive silicone breast implants: Safety and effectiveness at 5 to 9 years after implantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:1281–7. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000239457.17721.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camirand A, Doucet J, Harris J. Breast augmentation: Compression – a very important factor in preventing capsular contracture. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:529–38. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199908000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marques M, Brown SA, Oliveira I, et al. Long-term follow-up of breast capsule contracture rates in cosmetic and reconstructive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:769–78. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e5f7bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burkhardt BR, Fried M, Schnur PL, et al. Capsules, infection, and intraluminal antibiotics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:43–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Netscher DT, Weizer G, Wigoda P, et al. Clinical relevance of positive breast periprosthetic cultures without overt infection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1125–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199510000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handel N, Jensen JA, Black Q, et al. The fate of breast implants: A critical analysis of complications and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1521–33. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199512000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collis N, Coleman D, Foo IT, et al. Ten-year review of a prospective randomized controlled trial of textured versus smooth subglandular silicone gel breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:786–91. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200009040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulz-Wendtland R, Becker N, Bock K, Anders K, Bautz W. Mammography screening. Radiologe. 2007;47:359–69. doi: 10.1007/s00117-007-1490-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klug SJ, Hetzer M, Blettner M. Screening for breast and cervical cancer in a large German city: Participation, motivation and knowledge of risk factors. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:70–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]