Abstract

The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) provides breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services to low-income and underserved women through a network of providers and health care organizations. Although the program serves women 40-64 years old for breast cancer screening and 21-64 years old for cervical cancer screening, the priority populations are women 50-64 years old for breast cancer and women who have never or rarely been screened for cervical cancer. From 1991 through 2011, the NBCCEDP provided screening and diagnostic services to more than 4.3 million women, diagnosing 54,276 breast cancers, 2554 cervical cancers, and 123,563 precancerous cervical lesions. A critical component of providing screening services is to ensure that all women with abnormal screening results receive appropriate and timely diagnostic evaluations. Case management is provided to assist women with overcoming barriers that would delay or prevent follow-up care. Women diagnosed with cancer receive treatment through the states' Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Programs (a special waiver for Medicaid) if they are eligible. The NBCCEDP has performance measures that serve as benchmarks to monitor the completeness and timeliness of care. More than 90% of the women receive complete diagnostic care and initiate treatment less than 30 days from the time of their diagnosis. Provision of effective screening and diagnostic services depends on effective program management, networks of providers throughout the community, and the use of evidence-based knowledge, procedures, and technologies.

Keywords: screening, breast cancer, cervical cancer, early detection, case management

Introduction

As the awareness of the cancer burden among women has grown, cancer screening services have become widely accepted as an important part of well women's health care services. Early detection of cancer or precancerous lesions can decrease morbidity and mortality, psychological burden, and economic costs to the individual and society.1-8 For screening tests to be acceptable, they must be effective. In addition, health care providers must understand the benefits and risks of screening.9-11

In 1990, the Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Reduction Act (Public Law 103-354) authorized the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to provide breast and cervical cancer screening services to low-income women who would not otherwise receive these services. In 1991, CDC began to provide funding to state health agencies through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP). The program currently funds all 50 states, the District of Columbia, 5 territories, and 11 tribal organizations.12

The NBCCEDP has consistently focused on providing high-quality screening and diagnostic services to women who are underserved and do not have access to these services.13 Key services include screening and diagnostic services for both breast and cervical cancer. This includes screening mammograms, clinical breast examinations, Papanicolaou (Pap) tests with or without human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, and pelvic examinations. The NBCCEDP generally follows the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines for breast and cervical cancer screening.14,15 Depending on the results of these initial tests, women may require further diagnostic procedures that include but are not limited to breast ultrasound, diagnostic mammograms, colposcopy, and tissue biopsies. A critical aspect of the NBCCEDP is ensuring that these services are provided in an appropriate and timely fashion.16,17 The NBCCEDP monitors its effectiveness and efficiency of screening services through a specific data collection and evaluation process.18,19 This article describes the women and services that the program has provided and the cancers or precancers diagnosed since 1991, including screening, diagnosis, and treatment initiation.

Population Served

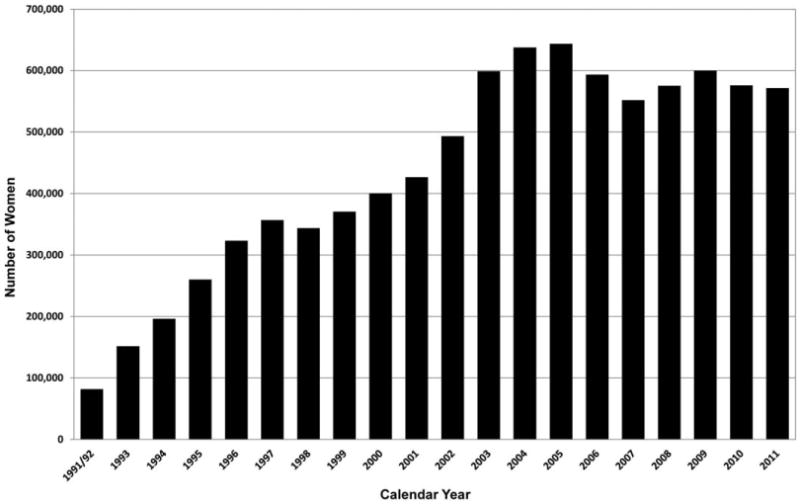

The NBCCEDP target population includes low-income women who are uninsured or underinsured. For breast cancer, women aged 40-64 years are eligible for services. For cervical cancer, women aged 21-64 years are eligible. Before the change in cervical cancer screening guidelines in 2012,15 women aged 18-20 were also eligible for cervical cancer screening. Because the burden of these cancers are higher in some groups, priority populations have been set to include women aged 50-64 years for breast cancer and those rarely or never screened for cervical cancer. Women older than 64 years are not eligible because they are insured by Medicare, which covers these clinical preventive services. However, if a woman cannot pay the premium to enroll in Medicare Part B and is income-eligible for the NBCCEDP, she may receive NBCCEDP services. Women who are older than age 65 currently account for approximately 1% of the women enrolled in the program. Since its inception, the NBCCEDP has served 4.3 million women and provided more than 10.7 million breast and cervical cancer screening examinations. The number of women served has increased from 82,000 in the first couple of years to more than 500,000 per year (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Number of women served through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program by year, 1991-2011.

Service Delivery: Breast Cancer

Although early detection and treatment reduce deaths from breast cancer.20 it has remained the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States for the past 4 decades.21,22 In 2010 (the latest year for which complete data are available), there were 206,966 women diagnosed with and 40,996 women who died from invasive breast cancer.23 Data from CDC's National Program of Cancer Registries and the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program showed that breast cancer incidence among women decreased by 2.0% annually from 1999 to 2005.21 US deaths from breast cancer have steadily declined, at 1.9% per year, from 1998 to 2009. Several reasons have been hypothesized for the decrease in incidence and mortality such as reduction in hormone replacement therapy use,24,25 early detection with mammography screening,20,26,27 and improvements in breast cancer therapy.28,29

Even though declines in both incidence of and deaths from breast cancer have been reported, there remain significant variations across racial and ethnic groups.30 In 2010, breast cancer incidence was highest among white women (119.5 per 100,000) compared with blacks (117.2), Hispanics (86.1), Asian/Pacific Islanders (APIs; 85.8), and American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs; 61.2).23 For the same year, breast cancer mortality was highest among black women (30.2 per 100,000) compared with white women (21.3), Hispanics (14.3), APIs (11.7), and AI/ANs (11.4).23 There are also differences in stage at diagnosis, with a higher percentage of blacks being diagnosed at a distant stage (8.1%) and a lower percentage (52.0%) being dianosed at a localized stage compared with other races.31

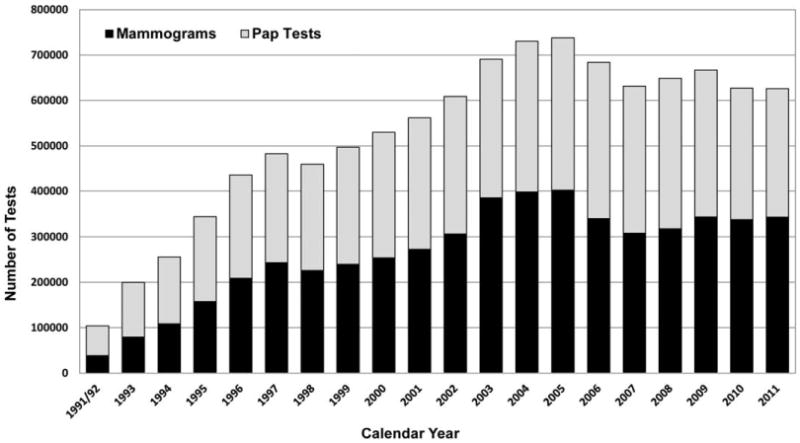

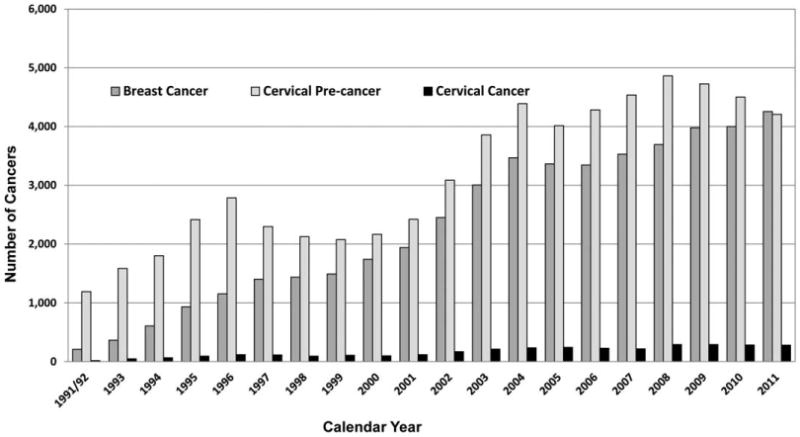

In the early years of the NBCCEDP, approximately 38,000 mammograms were provided across only few states (Fig. 2). During the last few years, the program has provided more than 300,000 mammograms annually. A major focus of the NBCCEDP is to help decrease disparities in breast cancer. Among the women who are screened for breast cancer, 47.7% are white non-Hispanic, followed by 24.5% Hispanic and 16.1% black non-Hispanic. APIs, AI/ANs, and multiracial or unknown races make up the remaining 11.6% (Table 1). From 1991 to 2011, the NBCCEDP diagnosed 54,276 breast cancers, with more than 16,000 being diagnosed over the past 5 years (Fig. 3). In 2011, 4255 invasive breast cancers were diagnosed, the most ever in 1 year. Breast cancer was diagnosed more often among those who had their initial mammogram through the NBCCEDP (Table 1). The number of women diagnosed with in situ carcinoma breast lesions has gone from 20 in the early years to more than 1500 in 2011. (data not shown) Among those who were diagnosed with breast cancer, women older than age 60, women who were white non-Hispanic, and women who were black non-Hispanic had the highest rates of cancerous and precancerous (carcinoma in situ) breast lesions diagnosed per 1000 mammograms (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Total number of mammograms and Pap tests provided by the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program by year, 1991-2011.

TABLE 1. Distribution of Abnormal Screening Tests and Rates of Cancers and Precancers Detected in the National Breast and Cervical Early Detection Program by Age and Race, 1991-2011.

| Cancer Detected (Rate/1000 Screens) | Precancersa Detected Rate/1000 Screens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Screening (%) | Initialb | Subsequentc | Initial | Subsequent | |

| Mammograms | |||||

| Race | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 47.7 | 12.4 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 1.6 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 16.1 | 10.1 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4.9 | 6.4 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 1.2 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4.5 | 5.3 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 1.7 |

| Hispanic | 24.5 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

| Multiracial/unknown | 2.2 | 9.7 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 1.7 |

| Age | |||||

| 40-49 | 21.3 | 8.7 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| 50-59 | 53.4 | 9.1 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 1.5 |

| 60-64 | 20.2 | 12.3 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 1.8 |

| ≥65 | 5.2 | 7.9 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.6 |

| Pap tests | |||||

| Race | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 50.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 9.7 | 3.3 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 2.4 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4.6 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 4.6 | 2.5 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 6.9 | 3.6 |

| Hispanic | 23.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 6.7 | 2.6 |

| Multiracial/unknown | 2.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 7.7 | 3.1 |

| Age | |||||

| 18-29 | 7.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 27.1 | 10.2 |

| 30-39 | 9.7 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 14.4 | 6.7 |

| 40-49 | 34.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 6.4 | 3.2 |

| 50-59 | 34.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 1.9 |

| 60-64 | 11.4 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 1.5 |

| ≥65 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

Precancers include DCIS and LCIS under mammograms and CIN1, CIN2, CIN3, and CIS under Pap tests.

Initial refers to the women's first screen performed by the NBCCEDP.

Subsequent refers to any additional NBCCEDP screenings after the initial screen by the NBCCEDP.

Figure 3.

Total number of breast cancers, cervical cancers, and cervical precancers detected by the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program by year, 1991-2011.

Service Delivery: Cervical Cancer

Although there has been a significant decrease in cervical cancer incidence and mortality over the past 50 years,21,32-35 cervical cancer still has a significant burden in the United States, ranking 13th in incidence and 14th for deaths among women.21 In 2010, there were 11,818 cervical cancers diagnosed, and 3939 women died from the disease.23 The decrease in deaths from cervical cancer has been attributed to the widespread implementation of Pap testing, which can detect cervical cancer early, when it is most treatable, and more importantly prevent cervical cancer by detecting precancerous changes (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and carcinoma in situ) that can be treated before developing into invasive disease.36 In 2012, the USPSTF included the use of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing in addition to Pap testing, known as cotesting, in their cervical cancer screening recommendations.16 For women ages 30-65, the USPSTF recommends cotesting every 5 years. The NBCCEDP has recently adopted the new screening recommendations with the goal of increasing the number of programeligible women who can be screened and improving the outcomes of cervical cancer screening.

Even though cervical cancer incidence is decreasing overall, there are significant disparities in burden of disease among different race/ethnicity groups and by socioeconomic status.21 Cervical cancer incidence rates were highest among blacks (9.8 per 100,000) and Hispanics (9.6), followed by whites (7.2), AI/ANs (6.3), and APIs (6.3).23 Death rates were highest among blacks at 3.9, followed by Hispanics and AI/ANs at 2.6 and 2.2, respectively, and lowest among whites (2.1), and APIs (1.7). Cervical cancer rates were also highest in areas with the lowest socioeconomic status.37

As the NBCCEDP works to decrease disparities in breast cancer, it also focuses on disparities in cervical cancer by targeting low-income women who are rarely or never screened. These women account for a large portion of cervical cancer cases.38 In the early years, NBCCEDP provided more than 65,000 Pap tests (Fig. 2) across a few states and now provides approximately 300,000 Pap tests nationwide each year. Of the women receiving Pap testing, 50.2% are white non-Hispanic, 23.1% Hispanic, 13.2 % black non-Hispanic, and 13.4% API, AI/AN, and multiracial or unknown (Table 1). Through 2011, 2554 cervical cancers were diagnosed and 123,563 precancerous cervical lesions were identified, of which 42% were high grade. Among women diagnosed with cervical cancer in the NBCCEDP, detection rates were highest among women who received their initial program screening test, white women, and women older than age 40 (Table 1). Younger women had higher rates of precancerous cervical lesions detected.

Service Delivery: Case Management for Abnormal Screening Results

The NBCCEDP ensures that all women with abnormal screening findings receive appropriate and timely diagnostic evaluation. The diagnostic tests required depend on the actual screening test results and may include repeat cytology, HPV testing, or colposcopy. Algorithms for diagnostic care using evidence-based standards of practice have been developed by professional medical organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network39 and the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology.40 The NBCCEDP grantees have developed and continue to maintain a network of providers and partnerships with health care organizations to guarantee timely access to these services and provide case management services to assist women. Overcoming these barriers allows women to complete follow-up without excessive delays.41,42

The NBCCEDP has also established quality measures that serve as benchmarks for timeliness and completeness of care.18,19 The NBCCEDP has a set standard that the timeline from abnormal screening result to final diagnosis is 60 days for breast cancer screening and 90 days for cervical cancer screening. The longer time interval for cervical cancer screening is a result of the limited colposcopy capacity and more extensive diagnostic steps required for some cervical cytology results. A recent study showed that the median time from abnormal breast cancer screening results to definitive diagnosis is 23 days.16 For cervical cancer screening, the average time to diagnosis is 48 days.17 The standard for completeness of care is that 90% of all women with abnormal screening results receive complete diagnostic evaluation. Overall, the NBCCEDP has greater than 90% completion of diagnostic care each year. (data not shown)

Service Delivery: Treatment Referral

Before passage of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment and Prevention Act of 2000, program staff had to arrange for treatment for women who were diagnosed with precancers or cancer.43 In many situations, case managers had to identify practitioners and facilities willing to donate their services; coordinate with public assistance programs, publicly funded hospitals, and county indigent funds; or develop payment plans. Some case managers indicated that increases in managed care made it difficult for individual providers to donate services or reduced-cost care. In a study of 7 state programs (CA, MI, MN, NC, NM, NY, TX) for women diagnosed with breast or cervical precancer/cancer through NBCCEDP, a variety of means were used to obtain treatment and even for some of the more complicated diagnostic procedures needed.43

In 2000, Congress passed the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Act (Public Law 106-354), which allowed states to use Medicaid services to cover treatment for women diagnosed with precancer or cancer through the NBCCEDP. By 2003, all states had approved the Medicaid waiver to cover treatment. Therefore, treatment services became available for women who met state Medicaid qualifications. The NBCCEDP grantees assist these women with enrollment into the Medicaid Treatment Program and with obtaining a referral to a health care provider for treatment. The NBCCEDP has set standards that women diagnosed with precancerous disease or invasive cancer must initiate treatment within 60 days from the day of the final diagnosis. In the most recent analysis of program data, the median time from diagnosis to treatment for invasive breast and cervical cancer was 14 and 21 days, respectively.16,17

State Example: The Wisconsin Well Woman Program

The Wisconsin Well Woman Program (WWWP) was established in 1993 with funding from the CDC's National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP). The WWWP has developed a strong capacity for addressing the critical breast and cervical cancer screening needs of low-income women in underserved communities throughout Wisconsin. The WWWP's current recruitment, public education, and screening activities are focused on women ages 45-64 who are uninsured or underinsured and whose income is at or below 250% of the federal poverty level. The WWWP is working to reach more women who are African American, Asian (particularly Hmong), Hispanic, and Native American. These population groups make up 14% of Wisconsin's 5.7 million residents. The program is also working on reaching more women who live in rural areas.

The WWWP is a decentralized statewide screening program with local coordinating agencies covering the state's 72 counties and 11 tribes in 5 public health regions. The majority (about 90%) of local coordinating agencies are local, primarily county health departments. The remainder include tribal agencies, a hospital, a city health department, and community-based organizations. The local coordinating agencies have designated a coordinator who is responsible for implementing local activities. The local coordinators serve as the initial contact for the WWWP in their county or tribal area. They determine a woman's eligibility for the program and are active in outreach, recruitment, and education activities. In addition, they help program clients navigate the health care system, support the program providers in their area, and provide case management for women with abnormal screening results.

The WWWP has developed a network of more than 1060 provider sites statewide for breast and cervical cancer screening in order to maintain screening services within a 50-mile radius of a woman's residence. The WWWP provider network includes ambulatory surgery centers, family planning clinics, federally qualified health centers, hospitals, independent laboratories, mammography facilities, pathologists, radiologists, nurse practitioners, rural health clinics, and tribal health clinics. Covered services are available from participating providers at no cost to WWWP clients.

The WWWP has provided more than 490,000 examinations to more than 70,000 Wisconsin women since the program began providing screening services on June 1, 1994. Program data indicate that over the last 18 years, 74% of the women receiving program mammo grams were white, 12% were black, and almost 3% were Native American. Hispanic women accounted for 11% of program mammograms. Over this period, the WWWP has diagnosed 1023 invasive breast cancers and 94 invasive cervical cancers. The women diagnosed with cancer were from all racial and ethnic groups and resided throughout the state's 72 counties. On January 1, 2002, Wisconsin implemented the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000, known as Wisconsin Well Woman Medicaid. More than 1000 women have accessed treatment through this program to date. Presumptive eligibility is available for women who have been screened by a WWWP provider.

Discussion

The NBCCEDP has more than 20 years of experience providing high-quality breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services to low-income women who otherwise would not have access to these services. Provision of effective diagnostic and treatment services is dependent on excellent program management and networks of providers throughout the community. Although the NBCCEDP has served millions of women nationally, it currently only reaches about 13.2% of women eligible for breast cancer screening and 9.0 % of women eligible for cervical cancer screening.44,45 More recent analyses have shown that the eligible population has increased and that the proportion of women reached has decreased to 11.7% and 8.2%, respectively.46 Although there are other sources of screening services for underserved women, studies have shown that a large proportion of uninsured women do not receive the recommended screening.47,48

Breast and cervical cancer continue to be a significant health burden for women across the United States. Healthy People 2020 has set objectives for decreasing the annual rates of new cases diagnosed and deaths due to these cancers.49 Providing appropriate and timely clinical preventive services is essential to reducing the morbidity and mortality caused by these cancers. The burden of disease is even more pronounced among certain racial and ethnic groups and among those who do not have access of health care.21,30,37 To establish effective screening, management procedures requires using evidence-based knowledge, procedures, and technologies and applying them to all women with special emphasis on the disparate populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This Supplement edition of Cancer has been sponsored by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an Agency of the Department of Health and Human Services, under the Contract #200-2012-M-52408 00002.

Footnotes

This article has been contributed to by US Government employees and their work is in the public domain in the USA.

Conflict Of Interest Disclosures: The authors made no disclosures.

References

- 1.Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR, Dahman B, Feuer EJ, Mariotto A, Brown ML. Productivity costs of cancer mortality in the United States: 2000-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1763–1770. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekwueme DU, Chesson HW, Zhang KB, Balamurugan A. Years of potential life lost and productivity costs because of cancer mortality and for specific cancer sites where human papillomavirus may be a risk factor for carcinogenesis-United States, 2003. Cancer. 2008;113:2936–2945. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoerger TJ, Ekwueme DU, Miller JW, et al. Estimated effects of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program on breast cancer mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard DH, Ekwueme DU, Gardner JG, Tangka FK, Li C, Miller JW. The impact of a national program to provide free mammograms to low-income, uninsured women on breast cancer mortality rates. Cancer. 2010;116:4456–4462. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiner JF, Cavender TA, Nowels CT, et al. The impact of physical and psychosocial factors on work characteristics after cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17:138–147. doi: 10.1002/pon.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramanian S, Trogdon J, Ekwueme DU, Gardner JG, Whitmire JT, Rao C. Cost of cervical cancer treatment: implications for providing coverage to low-income women under the Medicaid expansion for cancer care. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20:400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramanian S, Trogdon J, Ekwueme DU, Gardner JG, Whitmire JT, Rao C. Cost of breast cancer treatment in Medicaid: implications for state programs providing coverage for low-income women. Med Care. 2011;49:89–95. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yabroff KR, Bradley CJ, Mariotto AB, Brown ML, Feuer EJ. Estimates and projections of value of life lost from cancer deaths in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1755–1762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1998–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. The benefits and harms of mammography screening: understanding the trade-offs. JAMA. 2010;303:164–165. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Croswell JM, Ransohoff DF, Kramer BS. Principles of cancer screening: lessons from history and study design issues. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:202–215. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee NC, Wong FL, Jamison PM, et al. Implementation of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: The beginning. Cancer. 2014;120(16 Suppl):2540–2548. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henson RM, Wyatt SW, Lee NC. The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: a comprehensive public health response to two major health issues for women. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1996;2:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Screening for Breast Cancer, Topic Page. [Accessed September 6, 2013];U S Preventive Services Task Force. 2010 Jul; Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsbrca.htm.

- 15.Screening for Breast Cancer, Topic Page. [Accessed September 6, 2013];U S Preventive Services Task Force. 2012 Apr; Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm.

- 16.Richardson LC, Royalty J, Howe W, Helsel W, Kammerer W, Benard VB. Timeliness of breast cancer diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1996-2005. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1769–1776. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benard VB, Howe W, Royalty J, Helsel W, Kammerer W, Richardson LC. Timeliness of cervical cancer diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:776–782. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeGroff A, Royalty J, Howe W, et al. When performance management works: a study of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Cancer. 2014;120(16 Suppl):2566–2574. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yancy B, DeGroff A, Royalty J, Marroulis S, Mattingly C, Benard VB. Using Data to Effectively Manage a National Screening Program. Cancer. 2014;120(16 Suppl):2575–2583. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, et al. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:727–737. W237–742. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:175–201. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Trends Progress Report-2011/2012 Update. National Institutes of Health, Dept of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. [Accessed June 4, 2014];United States Cancer Statistics: 1999-2010 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/index.aspx.

- 24.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Uratsu CS, Selby JV, Kushi LH, Herrinton LJ. Recent declines in hormone therapy utilization and breast cancer incidence: clinical and population-based evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:e49–e50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elmore JG, Fletcher SW. The risk of cancer risk prediction: “What is my risk of getting breast cancer”? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1673–1675. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otto SJ, Fracheboud J, Verbeek AL, et al. Mammography screening and risk of breast cancer death: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:66–73. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berry DA, Inoue L, Shen Y, et al. Modeling the impact of treatment and screening on U.S. breast cancer mortality: a Bayesian approach. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2006:30–36. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgj006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1784–1792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Vital signs: racial disparities in breast cancer severity–United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:922–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Cancer Institute. Fast Stats: An interactive tool for access to SEER cancer statistics. [Accessed August 15, 2013];Surveillance Research Program. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats.

- 32.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moyer VA for USPSTF. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:880–891. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontaine PL, Saslow D, King VJ. ACS/ASCCP/ASCP guidelines for the early detection of cervical cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:501, 506–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147–172. doi: 10.3322/caac.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierce Campbell CM, Menezes LJ, Paskett ED, Giuliano AR. Prevention of invasive cervical cancer in the United States: past, present, and future. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1402–1408. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eheman C, Henley SJ, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2008, featuring cancers associated with excess weight and lack of sufficient physical activity. Cancer. 2012;118:2338–2366. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fruchter RG, Boyce J, Hunt M. Missed opportunities for early diagnosis of cancer of the cervix. Am J Public Health. 1980;70:418–420. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.4.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [Accessed March 25, 2013];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis Version 1. 2013 Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf.

- 40.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17:S1–S27. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287d329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siegel EJ, Miller JW, Kahn K, Harris SE, Roland KB. Quality Assurance through Quality Improvement and Professional Development in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Cancer. 2014;120(16 Suppl):2584–2590. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lobb R, Allen JD, Emmons KM, Ayanian JZ. Timely care after an abnormal mammogram among low-income women in a public breast cancer screening program. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:521–528. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lantz PM, Richardson LC, Sever LE, et al. Mass screening in low-income populations: the challenges of securing diagnostic and treatment services in a national cancer screening program. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2000;25:451–471. doi: 10.1215/03616878-25-3-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tangka FK, Dalaker J, Chattopadhyay SK, et al. Meeting the mammography screening needs of underserved women: the performance of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program in 2002-2003 (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:1145–1154. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0058-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tangka FK, O'Hara B, Gardner JG, et al. Meeting the cervical cancer screening needs of underserved women: the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 2004-2006. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1081–1090. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. [Accessed February 15, 2013];National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, About the Program. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/about.htm.

- 47.Miller JW, King JB, Joseph DA, Richardson LC Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Breast cancer screening among adult women—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(Suppl):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Cancer screening - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed March 12, 2013];Healthy People 2020. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.