Abstract

Most current drug screening assays used to identify new drug candidates are 2D cell-based systems, even though such in vitro assays do not adequately recreate the in vivo complexity of 3D tissues. Inadequate representation of the human tissue environment during a preclinical test can result in inaccurate predictions of compound effects on overall tissue functionality. Screening for compound efficacy by focusing on a single pathway or protein target, coupled with difficulties in maintaining long-term 2D monolayers, can serve to exacerbate these issues when utilizing such simplistic model systems for physiological drug screening applications. Numerous studies have shown that cell responses to drugs in 3D culture are improved from those in 2D, with respect to modeling in vivo tissue functionality, which highlights the advantages of using 3D-based models for preclinical drug screens. In this review, we discuss the development of microengineered 3D tissue models which accurately mimic the physiological properties of native tissue samples, and highlight the advantages of using such 3D micro-tissue models over conventional cell-based assays for future drug screening applications. We also discuss biomimetic 3D environments, based-on engineered tissues as potential preclinical models for the development of more predictive drug screening assays for specific disease models.

Keywords: Microengineered 3D tissue models, high-throughput drug screening, biomimetic microenvironment, organ-on-chip, bio-nanotechnology

Introduction

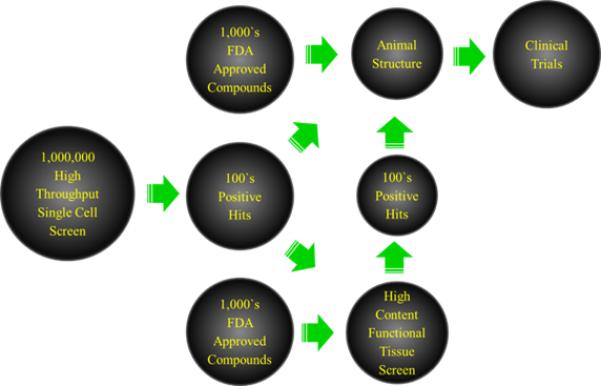

The conventional path of drug discovery from clinical trials to commercial realization is lengthy and extremely expensive. Only one out of an estimated 10,000 new chemical entities (NCEs) finally enters the market.1 Additionally, the number of NCEs approved by the FDA as new drugs fell by eighty-one percent between 1958 and 1979.2 Exploiting biochemical, gene expression, or single-cell assays, high-throughput drug screening (HTS) technologies have been enormously successful in developing selective and reliable assays of compounds in a rapid and economical manner.3 Indeed, the field has shown enough promise in scale, skill and speed to screen millions of compounds to date. However, such techniques are also subjected to considerable criticism as the methods employed typically rely on “one-gene, one-protein, one-target” approaches and therefore engender serious disadvantages: (1) it is difficult to effectively extrapolate the functional activity of a given compound, in vivo, since all drugs have effects on multiple intracellular second messenger pathways,4-6 (2) HTS techniques typically use two-dimensional (2-D) cell-based assays, which do not adequately recapitulate the in vivo complexity of three-dimensional (3-D) tissues,4 (3) HTS results, based on biochemical assays or gene expression, do not translate well into predictions of the overall impact of a compound on tissue or organ function due to the singular nature of the activity read-out. Consequently, any versatile attempt to address the inherent limitations in cell based assays for HTS applications is of considerable interest to the drug development industry. Lately, a realization that tissue based assays and organ-on-chip platforms for HTS screening will provide a new gateway to address problems associated with cell based assays has begun. Tissue engineering bridges biomimetic materials, stem cell technology, microfluidic systems and bio-imaging tools to generate functional 3-D tissues outside of the body that can be tuned in size, shape, and function to address required needs. High-throughput tissue based engineering is fast, relatively cheap, and is more ethically sound, requiring the use of fewer animals for effective investigation, as schematically represented in Fig. 1. Table 1 shows disease models of each engineered tissue model including materials, fabrication, and tested drug candidates. This review covers recent developments in the field of micro/nanotechnology, and gives examples of their applications in novel drug discovery protocols.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating high-throughput drug screening versus high content drug screening of bioactive compounds.

Table 1.

Application of bioengineered tissue models for HTS

| Type | Function | Disease Model | Material | Fabrication | References | Drug Candidates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Provides blood circulation to the rest of the body | Cardiovascular disease, arrhythmia | Hydrolitic Degradable scaffold such as polyglycolic acid (PGA) | Materials, including decellularized organs, seeded | [26], [109], [52], [110] | Beta Blockers, protein kinases for high-throughput |

| Lung | Provides oxygen and expels carbon dioxide | Asthma, Pulmonary edema | Decellularized ECM | Materials, including decellularized organs, seeded with progenitor and stem cells differentiated into lung tissues | [81], [82], [87], [88] | TRPV 4 blockers |

| Kidney | Regulates body fluid, pH, excretion of metabolic waste, migration | Drug Toxicology Immuno-reactivity Neophoro-toxicity | Biomedical Hydrogels Decelluarized porcine kidney Matrigel and collagen I | Stem cell-derived nephrons cultured ex vivo Magnetic levitation and ring closure High-throughput ecellularization system | [12], [24], [90], [109], [111] | Amiodarone-toxicity Ibuprofen sodium dodecyl sulfate Cisplatin, Gentamicin, Doxorubicin |

| Skin | Provides physical barrier and protects body against pathogens | Burn Injuries, necrotizing fasciitis, subdermal injury, melanogenesis | Decellularized matrices, Alloderm, Apligraf, Dermagraft, Epiccl, Integra Dermal Regeneration Template, OrCd, and TransCyt | Using decellularized matrices, skin cells, dermal fibroblasts | [11], [112], [113], [114], [115] | Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and dodecyl pyridinium chloride (DPC) |

| Muscle | Provides form, support, stability, and capability of directed movement to the body | Becker muscular dystrophy Duchenne muscular dystrophy Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy Facioscapulohumer al muscular dystrophy Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy Myotoniacongenita Myotonic dystrophy | Biodegradable polymers such as poly (lactide-co-glycolide), poly (caprolactone), polyphosphazenes, and composites of these polymers with each other and various inorganic compounds | Using synthetic matrices or decellularized natural matrices, seeding them with satellite cells | [63], [64], [69], [73], [74] | AVI-4658, Eteplirsen |

| Liver | Performs digestion, metabolism, immunity and the storage of nutrients within the body | Oxygen consumption and transport Hepatic disorders Liver toxicology and metabolism | Polyethylene glycol hydrogels Collagen | Microtissue suspension Perfusion system (bioreactor) made of polystyrene and polycarbonate scaffold and polyether aromatic polyurethane membrane | [91], [93], [94], [95] | Doxorubicin |

Principles of tissue engineering: The basics of fabricating biomimetic 3D tissue models

Tissue engineering uses tools from various fields of study to construct biologically suitable substitutes for organs and tissues which can in turn be employed in pharmaceutical, diagnostic, or research endeavors. Although applicable to drug screening applications, the eventual goal of such technologies is the development of autologous, engineered transplant material for replacing tissues that have been damaged by pathological or traumatic injury.7 The first successful attempt of such a technique was performed by Howard Green and colleagues who devised a method for engineering skin epidermis from patient biopsies. This was achieved by proliferating keratinocytes from a skin biopsy in co-culture with a feeder layer of mouse mesenchymal tissue.8 Most tissue engineering methods use living cells; having a large, reliable supply of these cells therefore is critical. Cells are usually obtained from donor tissues or from stem cells. Stem cells are a viable option because of the large quantity of cells they can produce, and the fact that they can differentiate into many different cell types (pluripotency).9

Adequate recreation of an in vivo environment in controlled in vitro conditions is accomplished by careful modulation of mechanical and chemical inputs within the designed culture platform. Having correct physical and chemical micro-cues affects the ability of cells to grow, proliferate, differentiate, and mature. A scaffold helps recreate the physical in vivo microenvironment, and enables the cells to grow with appropriate morphologies. Scaffolds enable cell attachment and migration, retention and presentation of biochemical factors, and also provide support through mechanical rigidity or flexibility, and allow for diffusion of nutrients, oxygen, and waste.7 Scaffolds for tissue engineering applications can be synthetic or natural. Many natural scaffolds currently in use employ biopolymers native to existing extracellular matrices (ECM). Some examples include protein based materials (e.g., collagen, fibrin, and gelatin) and polysaccharide-based materials (e.g., chitosan, alginate, glycosaminoglycans, hyaluronic acid, and methacrylate).10-13 Cross-linking agents (e.g., glutaraldehyde, water-soluble carbodiimide) may also be used in conjunction with these and other materials to reduce degradation rates. Some problems that certain natural scaffolds present include immunogenicity issues that could prevent biocompatibility.7 In addition to the actual scaffold, chemical cues and growth factors are also vital to stimulating expected tissue formation, and play a vital role in dictating how well engineered tissues develop. The ECM plays a pivotal role in directing cell movement by binding, retaining, and presenting growth factors to cells. Growth factors that are typically used include bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs),14 basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF-2),15 vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)16 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β).17 These growth factors can also be incorporated into the scaffold itself during establishment of the in vitro tissue. Other considerations affecting tissue formation include mechanical forces such as cyclic mechanical loading, geometric confinement, and shear stress.18-21

Once the appropriate scaffold is determined, the next step is typically to combine living cells with natural or synthetic scaffold polymers to build a 3-D model that is structurally, mechanically, and functionally representative of the native tissue. After fully seeding the scaffold with the desired cell type, time is required for the cells to mature and become functionally competent. The length of maturation time depends on the cell type, nutrient availability, and compatibility of the scaffold with type of cells used. After this process has occurred, the engineered tissue can be used for the specific research purpose it was designed for.

Types of engineered tissues

Establishing an in vitro model for tissue engineering applications can be a challenging task due to the number of considerations that must be taken into account when manufacturing engineered tissues. For example, cells respond to the topography of the substrate on which they are being cultured, which affects growth and differentiation.22-23 In addition, mechanical stiffness of the substrate and the type of ECM ligand can induce changes in tissue growth and responsiveness.24-25 Despite these difficulties, a wide variety of microengineered tissues have been produced capable of recreating biological function in controlled in vitro environments. Some of the most advanced engineered tissues are discussed here, as well as some less advanced systems which are of considerable interest to the drug development industry.

Cardiac tissue

One current area of research that has had significant breakthroughs is the development of an engineered cardiac tissue. Cardiovascular disease currently claims the most lives world-wide, and causes a major socioeconomic burden. In the U.S. alone, costs were estimated at US$ 297.7 billion in 2008, accounting for around 16% of the total health expenditure.26 It is therefore the most significant health issue that humanity faces. To help combat the threat of heart disease, interest has been sparked in the development of in vitro engineered cardiac tissues for drug screening and developmental studies, as well as for transplant solutions. Although cardiomyocytes have demonstrated the ability to automatically align and reconstruct the ordered structure of the native myocardium,27 bioengineered cardiovascular tissue typically involves the seeding of ventricular cardiomyocytes into biopolymer scaffolds to create ordered 3D structures capable of rhythmic contractile functionality in a single plane.28-32 Such constructs have been shown to integrate well with host tissue, when transplanted in vivo, thereby improving the functional competency of the damaged myocardium.33-35 Recent developments in human cardiac tissue engineering have also focused on developing improved methods for obtaining human cardiomyocyte populations. Significantly, substantial advances have been made in methods for differentiating human embryonic stem cells36-38 and human induced pluripotent stem cells into functional and physiologically relevant cardiomyocytes.39-41 Integration of these mature human cells with appropriate matrices has enabled the creation of tissues that have features characteristic of the in vivo human myocardium.42

Current methods for engineering cardiac tissue on scaffolds require cells found in the native cardiac environment, such as endothelial cells,33 smooth muscle cells,43 myofibroblasts,44 and fibroblasts.45 These cells need to be able to self-assemble in the engineered ECM scaffolding in order to generate functional tissues. One method of performing this is by using a hydrolytic degradable scaffold such as polyglycolic acid (PGA) as a substrate for the seeding of human cells.46 Biodegradable scaffolds, such as PGA, gradually degrade over time, incite little immune response and minimize the risk of inflammatory responses in the long term. In vivo development of blood vessels is directed by forces applied on them by their environment. Thus, development of an accurate vascular tissue model requires inter-tissue communication and correct recreation of cellular shear stresses and mechanical strains in vitro. Radial and longitudinal strain is caused by pulsatile flow, while shear stress on luminal wall surfaces is caused by steady state flow. These mechanical forces result in the alignment of endothelial cells in the direction of the shear. Through the use of bioreactors, it is possible to replicate these forces, and thereby influence endothelial cell alignment in vitro.47 Bioreactors which generate dynamic flow culture systems provide a nutrient rich environment in which external forces can be applied to cultures, thereby resulting in tissues with increased strength and longevity.48 Another requirement for creation of truly biomimetic cardiac tissue constructs is the effective mimicking of mechanical and structural properties of native cardiac ECM, composed of aligned collagen fibers with nano-scale diameters, to influence tissue architecture and electromechanical coupling. Therefore, Kim et al. reported the development and analysis of a nano-topographically controlled in vitro model of the myocardium that mimics the structural and functional properties of native myocardial tissue and specifically the underlying hydrogel architecture.49-51 The authors suggested that nanostructured polymeric substrata that closely mimic the extracellular matrix structure on which cardiac cells reside in vivo can be both very effective tools in investigating the basis for cardiac tissue engineering, thus facilitating stem cell-based therapy in the heart.

In spite of these achievements, use of engineered cardiac tissue for HT drug screening assays is still in early stages of development and remains a challenge. The major hindrance to the advancement of cardiac tissue engineering for such applications, is an inability to test parameters such as cell source variability, and mechanical, soluble and electrical stimuli in a high-throughput and combinatorial manner. Due to their size, centimeter-scale constructs are too expensive to use in high-throughput protocols, and require histological sectioning to visualize cellular and extracellular architecture, making rapid analysis difficult. Legant and Hansen reported an approach to fabricate arrays of tissue micro gauges (μTUG) and mini-engineered heart tissue (m-EHTs) to generate cardiac microtissues embedded in collagen/fibrin 3D matrices.5, 6, 52 The authors demonstrated that their microtissue assay was suitable for high-throughput monitoring of low-volume drug screening and tissue morphogenesis studies (Fig. 2). These critical developments in manufacturing of engineered cardiac tissue could enhance preclinical testing of drugs in the future and present opportunities for replacement of damaged tissues in living humans.53

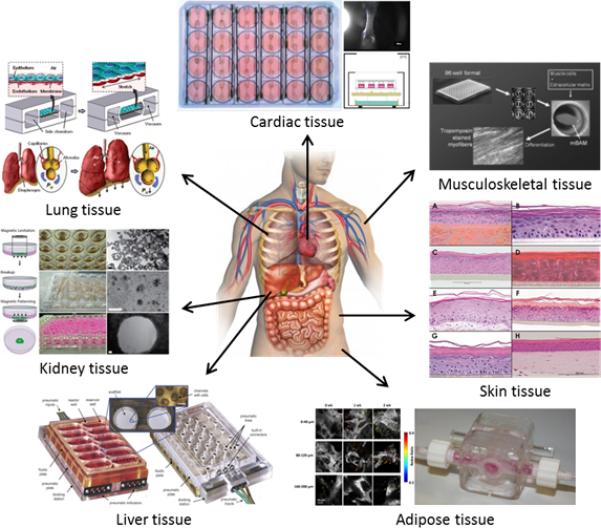

Fig. 2.

Illustration of high-throughput tissue engineering, highlighting the development of bioengineered tissue models including Cardiac (fibrin-based mini engineered heart tissue (FBMEs) array),52 Lung (lung-on-a-chip),89 Kidney (ring closure assay with magnetic levitation),111 Liver (perfused multiwell bioreactor, 3DKUBE™),94 Adipose (perfusion bioreactor),97 Skin (3D in vitro reconstructed skin models: EpiSkin (a), SkinEthic RHE (b), EpiDerm (c), EST1000 (d), Phenion®FT (e), OS-Rep (f), Straticell (g), andStrataTest (h)),115 and Muscle (Bioartificial muscle (mBAMs) on µposts).59 Reprinted with permission from each Reference.

Musculoskeletal tissue

Degenerative muscular disorders are debilitating conditions that typically lead to death. Recently, engineered musculoskeletal tissues have been highlighted as a means to improve clinical therapies and treatments for such muscle wasting diseases by providing controlled platforms with which to determine the capacity for novel compounds to improve tissue repair and myofiber regeneration.54 In order to engineer the muscle itself, a stable mechanical platform must be used. For physiologically correct musculoskeletal development, this mechanical platform should integrate bone,55 cartilage,56 ligament,57 and intervertebral disc engineering.58 Mechanical properties that need to be taken into account when the tissues are engineered include mechanical testing for stress–strain, compression, viscoelastic, and shear stress properties.59

Engineered musculoskeletal tissues often utilize immortalized cells, such as C2C12s, due to their robust nature, reduced variability, cost effectiveness, and ready availability.60 However, to improve biomimicity, recent work has focused on the use of primary rodent and human muscle precursor cells (satellite cells) for tissue engineering applications.61 Despite the fact that embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell sources have been shown to differentiate down the skeletal muscle lineage,62 satellite cells are currently the only cell source with a demonstrable ability to generate functional skeletal muscle tissue and, once activated, to proliferate as myoblasts and self-renew as to replenish the quiescent satellite cell population.63, 64

Scaffolds employed in skeletal muscle engineering can be natural, such as collagen,65 fibrin,66 Matrigel,67 or synthetic polymers like poly (lactide-co-glycolide),68 and poly (caprolactone);69 composites of these polymers integrated with various inorganic compounds is also possible.70 Engineering of ordered uniaxial musculoskeletal tissues is based on the understanding that cells will align parallel to the passive tensions that develop within 3-D matrices.71 The formation of cell seeded scaffold matrices around uniaxial adhesion points promotes the generation of ordered mechanical strain between these sites as cultured cells begin to remodel the polymer fibers surrounding them. Myoblasts seeded into these environments respond to these mechanical cues and reorganize themselves along the lines of principle stain within the scaffold. When the culture medium is switched to a low serum differentiation medium, the myoblasts fuse into myotubes aligned between the adhesion points in the construct. These miniature bioartificial muscles (mBAMs) are capable of generating directed forces when stimulated via broad-field electrical stimulation67 or by co-cultured motoneruons.72 Such skeletal muscle constructs can be maintained under tension for weeks in vitro, and the forces generated by engineered contractile tissues can be measured using force transducers for real-time evaluation of functional performance in response to therapeutic treatment.59, 73

A substantial contribution to the development of high-throughput skeletal muscle screens was made by Vandenburgh et al., when they reported a new prototype 96-well assay system for tissue-engineered skeletal muscle in which force measurements could be made using a novel image-based motion detection technology. This approach provides a nondestructive and sensitive method for measuring muscle force generation changes during chronic exposure to drug candidates. The authors demonstrated that most cells align in parallel to the passive tensions developed in the collagen gel when it coalesces. Mixing proliferating myoblasts with extracellular matrix solutions, such as collagen or fibrin, and casting in a well with attachment posts results in a tubular structure attached to the two posts as the collagen coalesces away from the well sides (Fig. 2).68, 74 Using this system, the authors demonstrated mBAM myofiber hypertrophy and active force increases in response to insulin-like growth factor 1. In contrast, mBAM deterioration and weakness was observed with a cholesterol-lowering statin. The results described in this study demonstrate the integration of tissue engineering and biomechanical testing into a single platform for the screening of compounds affecting muscle strength.

Despite the considerable recent progress in generating skeletal muscle screening systems, there is still a need to develop more advanced, integrated models for accurate prediction of performance in toxicity/ efficacy studies. The most significant challenges involve the development of fully matured skeletal muscle fibers to adequately model adult physiological architecture, and interaction with principal supporting tissues; most notably, vascular, myotendinous, and neuronal connections to engineered muscle need to be addressed. Recent work has demonstrated the successful development of skeletal muscle constructs capable of producing comparable force levels to that of native tissue,116 however, this work utilizes rodent cells, and no similar study has yet been published using human cells. Likewise, models investigating vascular infiltration,116, 117 neuromuscular junction formation118, 119 and myotendinous junction connectivity120 have all been published. All of these studies however, suffer either from non-human cell sources or a lack of high-throughput functionality. Adaptation of these systems to account for these limitations will be crucial to the development of predictive skeletal tissue models for future high throughput drug screening applications.

Skin tissue

Skin not only represents one of the most important and largest tissues in the human body for protecting against harmful materials (toxic pathogens and organisms), but also offers the most direct means for transportation of drugs/reagents/ingredients into the body via either topical or transdermal delivery methods. In recent years, innovations in drug delivery systems have seen enormous growth, involving both new and existing drug compounds. Furthermore, research and development into human skin equivalents for effective modeling of this delivery method has advanced in parallel with those for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications.75 For the last decade, there has been significant interest in improving engineered skin, involving pigmented,76 vascularized,77 and immune competent dermal structures78 as well as an innovated skin models79 including engineered human skin equivalents containing both Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells and engineered epidermal nerve fibers. For instance, a reconstructed human epidermal (RHE) model has been introduced as a living skin equivalent, a 3D organotypic model that can be used to investigate many aspects of cutaneous biology. This model was generated from primary human keratinocytes on a collagen substrate containing human dermal fibroblasts, grown at the air-liquid interface, which allow full epidermal stratification and epidermal-dermal interactions to occur.123 Moreover, a multi-layered human tissue composed of both epithermal and dermal components has also been reported.115 In this model, the epidermal compartment was generated by the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, which serves as a unique, consistent and unlimited source of human keratinocyte progenitors. The dermal compartment of the model contained normal human dermal fibroblasts distributed throughout a fibrous collagen matrix. These models most closely mimic normal skin, allowing the topical application and skin irritancy testing of a great variety of products used in daily life. However, most current tissue engineered skin models, containing only one or two cell types, lack skin appendages, and therefor are insufficient to adequately mimic the complexity of human skin. Various aspects of state of the art advanced human skin equivalents are reviewed and discussed in detail by Zhang and colleagues.10

Transdermal delivery systems are one of the noted innovations which entertain significant advantages over orally administered drugs. Due to low skin permeability, the widespread application of transdermal drug delivery is limited. Many chemicals have been used to enhance skin permeability, but only are few put in to practice. Although combinations of chemicals are likely to work efficiently to enhance skin permeability compared to individual enhancers, the identification of efficient enhancer combinations is challenging because of the interaction between chemical enhancers and the skin in a complex subject. In the absence of fundamental knowledge of such interactions, researchers rely on rapid high-throughput methods to screen various enhancer combinations for their effectiveness. Karande et al., reported a method11 that is at least 50-fold more efficient in terms of skin utilization, and up to 30-fold more efficient in terms of hold-up times than current methods for formulation screening (Franz diffusion cells). The method is developed based on skin conductivity and mannitol penetration into the skin. This method was used to perform at least 100 simultaneous tests per day. Detailed studies were performed using two model enhancers, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and dodecyl pyridinium chloride (DPC). The predictions of this high-throughput method were validated using Franz diffusion cells. The results of this HTS revealed that mixtures of SLS and DPC are significantly more effective at enhancing transdermal transport compared with each of them applied in isolation. Maximum efficiency was observed with near-equimolar mixtures of SLS: DPC. The predictions of the HTP method correlated well with those made using Franz diffusion cells. Specifically, the effect of surfactant mixtures on skin conductivity and mannitol permeability measured using Franz cells also showed a maximum at near-equimolar mixtures of SLS: DPC. The authors claim that the HTP method is particularly beneficial for testing mixtures of enhancers whose efficiency may be difficult to predict a priori. Since appropriate mixtures of enhancers are likely to be more efficient than their individual components, the HTP method may be used to discover novel enhancers comprising of enhancer mixtures. This method may also be used to explore synergies between various enhancers, which may lead to novel formulations for transdermal drug delivery as well as cosmetic agents.

Lung tissue

Lung diseases and respiratory problems are responsible for 480,000 deaths per year in the U.S. alone.80 Adult lung tissue has a limited capacity for regeneration in the case of injury beyond the cellular or microscopic level. Currently, the only clinically acceptable method to replace damaged lung tissue is via a lung transplant, which presents the problem of adequate supply of donors and immune system incompatibility. Tissue engineering of functional lung constructs would be of tremendous benefit for tissue replacement applications, but would also have substantial implications to the development of preclinical screens for evaluating aerosol drug delivery methods and the effect of such drugs on respiratory function. Such models would require lung specific cells maintained in an appropriate 3-D geometry, and integrated with a suitable microvascular barrier to separate blood from air, as well as adequate mechanical properties to facilitate ventilation at pressure that is physiologically normal.81 Recent developments in lung tissue engineering concern identification of endogenous and exogenous populations of lung stem cells that can be used for fabrication of tissues.82

The first step to engineering lung tissue is having an appropriate source for cells. Some of the required cells can be generated from embryonic stem cells, endogenous pulmonary stem cells, and extra pulmonary stem cells.83-85 Embryonic stem cells have been shown to differentiate down a specific lung cell lineage by culturing them with differentiated lung cell extracts.86 Differentiating cells into specific lung tissue lineages remains a challenge due to a lack of understanding of the influence of priming treatments, lung growth factors, or the type of culture environment necessary to promote functional lung cell differentiation. Further research needs to be conducted in the field of lung stem cell differentiation before it can proceed to the point where it is clinically relevant. Cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions and communication play a significant role in the regeneration of tissues through activation/ inhibition of endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine pathways. Directing stem cell differentiation toward lung tissue lineages using defined media, co-cultures or conditioned media is time consuming, and there are no guarantees that the type of cell achieved will fully recapitulate the physiology and function of its in vivo counterpart. Furthermore, low yields of desired cell types necessitate further research into better conditions for the growth of these types of cells.

In order to engineer lung tissue, it is important to have a scaffold on which lung tissue can be grown effectively. An appropriate scaffold is vital as it supports the structure of the tissue and also influences the development, growth, physiology, and response to injury of the seeded cells. Proteins in the ECM have different functions, including providing tensile strength, enabling metabolic activity, cell migration, and facilitating the oxygenation of tissues and removal of waste products. Developing a scaffold for lung tissue engineering must therefore take into consideration such factors as elasticity of the scaffold, biocompatibility, and absorption kinetics of the material. Particularly important is the elasticity of the matrix, because if the tissue is to take part in respiration, then it cannot alter the functionality of native tissues by modifying their elastic recoil. If the scaffolding is not as elastic as the tissue around it, it could potentially restrict breathing as scar tissue typically does in patients with sarcoidosis or pulmonary fibrosis. Thus, the scaffold may need to be made out of a combination of several materials to accommodate the many functional requirements of the engineered tissue. Synthetic, as well as natural, materials have been used for lung tissue fabrication. Examples of natural materials include collagen, Matrigel, and Gelfoam.87 One example of a synthetic matrix is porous poly (dimethylsiloxane) chips that support human lung epithelial cells and capillary endothelial cells and mimic alveolar function. One limitation of artificial scaffolds such as this, however, is that they do not effectively replicate the intricacy of lung architecture. The most effective efforts in lung tissue engineering so far have got around this issue by employing decellularized cadaveric native lung ECM. Use of decellularized native tissue ECM allows for the retention of the in vivo architecture, and also incorporates ligands and bioactive molecules into the scaffold which in turn encourages cells to assemble into more physiologically relevant groupings and so function more effectively. The process of manufacturing lung tissue in this manner involves the enzymatic decellularization of native lung tissue, which removes cells but allows for retention of alveolar microarchitecture.88 As demonstrated by Petersen and his colleagues, it is possible to create vascular and pulmonary epithelia on a natural scaffold through use of a bioreactor that replicates the mechanical, physical, and biochemical forces present in the in vivo environment. They found that when this was done, seeded cells organized themselves as they would have in vivo and the epithelial cells were able to repopulate the decellularized ECM effectively. In fact, when the tissue was implanted into rats, it was observed that the engineered construct participated in gas exchange along with the native tissue. This remarkable feat demonstrates that it should be possible in the near future for such engineered lung tissue to be used for lung replacement or transplantation in humans. For another example, Huh et al. reported a biomimetic microdevice that reconstitutes organ-level lung functions to create a clinically relevant human disease model-on-a-chip that mimics pulmonary edema for use in preclinical drug toxicity and efficacy studies.89 The authors developed a microfluidic device which reconstitutes the alveolar capillary interface of the human lung, and consists of microchannels lined by closely apposed layers of human pulmonary epithelial and endothelial cells that experience air and fluid flow, as well as cyclic mechanical strain to mimic normal breathing motions (Fig. 2). This on-chip pulmonary edema model effectively reproduces the intra-alveolar fluid accumulation, fibrin deposition, and impaired gas exchange that have been observed in living edematous lungs after 2 to 8 days of interleukin-2 (IL-2) therapy in humans. These data suggest that mechanical forces associated with physiological breathing motions play a crucial role in the development of increased vascular leakage that leads to pulmonary edema, and that circulating immune cells are not required for the development of this disease. This microengineering approach allows investigators to utilize the simplest model possible that retains physiological relevance, with the potential to add organ complexity to the system as necessary; an approach which is not possible in animal models. Moreover, this miniaturized organ system could be arrayed for HTS to model complex diseases correlated with other organs and to predict different drug efficacies and toxicities in humans.

Kidney tissue

Renal failure is a battle that many people face due to disease or through disorder. Given the extremely high failure rate of prospective drug compounds in early phase clinical trials due to unexpected human toxicity, it is imperative that more relevant human models be developed to better predict a drug's toxicity and availability. Current pre-clinical methods of determining renal toxicity include 2-D cell cultures and animal models, as described for other tissues and organ systems, both of these methods are incapable of fully recapitulating the in vivo human response to drugs, which in turn contributes to the high failure rate upon transition to clinical trials. Current tissue engineering methods to address this problem are focused on creating bioengineered 3-D kidney tissue models using immortalized human renal cortical epithelial cells, with kidney functions similar to that found in vivo,90 and on creating renal organoids from single-suspensions derived from E11.5 kidneys.24 To facilitate the introduction of engineered kidney tissues on a larger scale, development of a more physiologically accurate model is also required.

3-D kidney tissue constructs have been developed in a 12-well transwell dish format, with 0.4 mm porous polycarbonate membranes utilizing both Matrigel and rat tail collagen I.90 Each transwell insert was coated with a 50:50 mix of both ECMs, and then NKi-2 cells were mixed with the developed ECM solution and added to each coated transwell insert. This bioengineered 3-D human renal tissue system shows functional and morphological similarity to human kidney tissue in vivo and has been used as a predictor of human nephrotoxicity. The results obtained using this system highlight an increased sensitivity to lower drug concentrations than the same cells grown in 2-D. This observation, coupled with longer term viability, indicate the greater suitability of this model for chronic toxicity studies over conventional 2-D systems.

One of the greatest challenges still to face in generating engineered renal tissues is the development of a supporting scaffold that accurately recapitulates the biochemical, spatial and vascular relationships of the native kidney extracellular matrix. An organoid-derived 3-D culture of kidney proximal tubules (PTs) within commercial biomedical-grade hydrogels that maintains native cellular interactions in tissue context, regulating phenotypic stability of primary cells in vitro has been developed to realize a more physiologically-relevant response to nephrotoxic agent exposure, with production of toxicity biomarkers found in vivo. Importantly, proximal tubule cell viability in these 3-D organoid hydrogel constructs requires gentle gel encapsulation conditions, consistent diffusion of oxygen and nutrients throughout the gel-tubule construct, and miniaturized construct size and optimized geometry to facilitate nutrient transport.24 This method allows for the creation of in vitro structures that parallel their in vivo counterparts, thereby suggesting promise for the development of future implantable engineered renal tissues in humans. Additionally, further exploration using the 3-D organoid model may provide insight that would lead to a greater understanding of cell organizational and communication roles in tissue functional maintenance. This level of understanding further informs the design parameters for improved bioreactor models for 3-D cell scaffolds popular in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. The model should also facilitate establishment of cell culture models better suited to the direct assessment and comparison of different in vivo and in vitro pathophysiology and tissue damage biomarkers. This biotechnology is of substantial importance to advancing preclinical drug development protocols since many drugs fail late in trial phases due to kidney toxicity. Such models could be used to study the nephrotoxicity at early preclinical development stages, and prevent harmful candidates from making it past preliminary stages of drug testing and into human trials. Moreover, Sullivan et al. developed a high-throughput decellularization system to ensure reproducibility,12 which is critical in the production of a bioengineered whole functional kidney. The authors reported that the goal of this study was to develop an effective porcine kidney decellularization method for whole organ engineering using either the ionic (SDS) or non-ionic (Triton X-100) detergents. The details of the high throughput method are shown in Fig.2.111 These biomimetic primary kidney models have broad applicability to high-throughput drug and biomarker nephrotoxicity screening, as well as more mechanistic drug toxicology, pharmacology, and metabolism studies in human kidneys.

Liver tissue

Alcoholism takes a substantial toll on proper liver function, as do diseases such as jaundice and Hepatitis A, B, and C. Such conditions cause irreversible damage to the liver tissue and necessitate transplant surgery to ensure continued functionality. Engineered liver tissue constructs could potentially put an end to lack of donor issues with liver transplant solutions, and could reduce the number of people suffering from liver illnesses worldwide. Importantly, given the role the liver plays in metabolizing drug compounds in mammalian systems, tissue engineered models of hepatic tissue also have an important potential role in preclinical studies for predicting drug metabolism in vitro.

In order to manufacture liver tissue for use in both in vivo and in vitro applications, it is necessary to have an appropriate matrix for the seeded cells. Such a matrix is provided by photopolymerizable poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG). PEG hydrogels can be altered to mimic the in vivo environment of liver tissue.91 Furthermore, the processed hydrogels can be used to guide cell movement, and can regulate the morphology, cytoskeletal architecture and function of the engineered tissue. Current approaches to liver tissue engineering utilize adult hepatocytes, which have a large proliferative capability.92 To promote tissue formation ex vivo, matrices need to be treated with serum and cytosol collected from livers which underwent pHx, in addition to amino acids, growth factors, hormones, vitamins, trace metals, and serum proteins.

In order for engineering of the tissue to be successful, a specific cell population must also be used. Currently, embryonic stem cells can be directed to differentiate into the hepatic lineage through addition of growth factors. Current tissue engineering results in the formation of spheroids with a ~50 μm diameter which gradually fuse into larger 150 - 175 μm spheroids over several weeks. These spheroids result in better functionality than a normal monolayer culture. When the spheroids are transferred to a collagen surface, they break down and dedifferentiate. Encapsulating spheroids can control cell-cell interactions.93 Currently, limitations of this method of liver tissue engineering include necrosis in the center of spheroids due to lack of nutrients and an inability to transport waste products out of the construct. Current research is focused on developing ways to improve spheroid formation. Though many types of perfusion bioreactors for 3-D culture have been developed, they are generally limited in throughput and often complicated to use. Domansky et al. reported an approach94 that adapts 3-D models to an easy-to-use, multiwell plate format suitable for higher throughput applications. They described the design and function of a perfused multiwell plate containing 12 fluidically isolated bioreactors that each accommodates 400,000 – 600,000 cells (Fig. 2). The higher throughput capability of this perfused 3-D liver multiwell system is beneficial for conducting assays for liver toxicology and metabolism, and can be used to model hepatic disorders, cancer, and other human diseases. The authors claim that even though they have described the design and function of an array of 24 wells, the concept is scalable to a plate with a higher number of wells, such as a 96-well plate. They have also mentioned that the approach can be extended for perfusion culture of other high metabolically active cell types such as kidney, heart, or brain cells. The Bhatia group have also developed a high-throughput platform to support 3-D micro-tissues representing multiple stages of liver development and disease, including embryonic stem cells, bipotential hepatic progenitors, mature hepatocytes, and hepatoma cells photoencapsulated in polyethylene glycol hydrogels.95 This platform facilitates the high n, quantitative, multiplexed assessment of suspensions of miniaturized 3-D encapsulated cellular constructs. This 3-D micro-tissue is designed to represent small-scale units of multicellular tissue and is engineered by photoencapsulating 500 – 1000 cells in an encoded polyethylene glycol hydrogel. Expanded populational analysis and sorting of multicellular engineered micro-tissues can then be employed for assessment of cellular toxicity and cancer responsiveness to drug interactions.

To date, attempts to engineer functional liver constructs have primarily focused on either microscale designs, incorporating most organ-on-a-chip technologies, or macroscale reseeding of decellularized matrices. The further advancement of microscale constructs toward more clinically relevant tissues (either for in vivo transplantation or in vitro predictive drug and disease modeling studies) is predicated on their integration with effective vascular networks to support the growth of tissue size and complexity. Similarly, current efforts to seed decellularized ECM structures with liver cells to create new tissues have suffered from an inability to effectively regenerate the refined microarchitectures of the native tissue. The development of a correctly functioning capillary network to facilitate the effective circulation of nutrients and waste therefore remains a major challenge in the development of more biologically accurate liver models for both high throughput applications as well as clinical and basic science studies. The current status of liver engineering is discussed in more detail by Sudo.121

Adipose tissue

Soft tissue defects pose a major problem for patients and doctors. On an annual basis, millions of patients need to seek medical treatments, typically involving surgery, in order to restore soft tissue defects that result from conditions such as cancer, traumatic injury, illnesses, or congenital defects. In the past, either silicone or saline substitutes have been used to correct such issues but, with the advent of tissue engineering, new procedures can allow for adipose tissue to be directly inserted into the wound site.96 For drug development applications, adipose tissue is an important consideration, since fat has a significant impact on the distribution and accumulation of administered compounds and their metabolites.

The discussion of adipose tissue engineering has been an area of relatively intense research for the past decade. One major challenge that needs to be taken into consideration during development of engineered adipose tissue is the vascularization of the tissue itself. Without removing waste and supplying oxygen and nutrients efficiently, the engineered tissue will be unable to survive in vivo, let alone in vitro. In the past several years, researches have typically made use of human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs), which are a promising source for tissue engineering. These hASCs can differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, and myogenic cells. It is possible to develop an alginate based microencapsulation system with a liquid core that can immuno-isolate the immobilized cells from the host tissue with the surface shells impenetrable to cells. By combining the vascularization aspect and the scaffold design, a new method of engineering adipose tissue has been created. Using alginate as the scaffold for the microsphere, and by coating it with collagen, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells, a vascularized capsule tissue system was created and proved viable in a mouse model. Such a model could be translated to humans in the future and could prove useful in therapeutic and research endeavors.

Recently, A. W. Kyle et al. developed a perfusion bioreactor system compatible with two photon imaging for non-invasive assessment of engineered human adipose tissue structure and function in vitro.97 The details of the experimental setup and results are illustrated in Fig. 2. The group engineered in vitro three dimensional (3-D) vascularized human adipose tissues within a perfusion environment, and automatically quantified the fluctuations in endogenous metabolic markers using two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF). They analyzed depth-resolved image stacks for redox ratio metabolic profiling and compared results to prior analyses performed on 3-D engineered adipose tissue in static culture conditions. Additionally, traditional assessments with H&E staining were used to qualitatively measure extracellular matrix generation and cell density with respect to location within the tissue. The distribution of cells within the tissue and average cellular redox ratios were different between static and perfusion cultures, while the trends of decreased redox ratio and increased cellular proliferation with time in both static and perfusion cultures were similar. These results are aimed at establishing a basis for noninvasive optical tracking of tissue structure and function in vitro, which can be applied to future studies to assess tissue development or drug toxicity screening and disease progression. This approach for combining quantitative metabolic imaging and 3-D tissue engineering using perfusion bioreactors has been proposed as a step toward the generation of low-cost, high throughput methods to study more physiologically relevant engineered human tissue systems in applications such as disease models, drug screening, or developmental biology.

One of the major difficulties associated with modeling adipose tissues in vitro for HTS applications lies not in the effective modeling of the tissue itself, but of adequately accounting for its presence when modeling other tissue behaviors. Experiments with the environmental toxin naphthalene have demonstrated that 3T3-L1 adipocytes modulate the response of cultured lung cells to the compound when maintained in co-culture.122 Adipose cells likely alter the response of other cultured cell types to compound treatment through absorption of toxins and harmful metabolic by-products, such as hydrogen peroxide. Observations such as this serve to highlight the importance of accounting for adipose tissue modulation of compound action when seeking to accurately model and predict drug efficacy/ toxicity on engineered tissues in vitro.

Towards integrative biomimetic microenvironment for HTS applications with engineered tissue models

It is widely acknowledged that highly rigid and flat culture surfaces, with poorly defined surface chemistry, present in commonly used multi-well plates and culture flasks, do not present cells with bio-mimetic mechanical or chemical microenvironments capable of facilitating the advanced functional maturation of seeded cells. Recent advances in nanofabrication techniques have led to novel in vitro cell culture models that better mimic the in vivo cellular microenvironment by providing physiologically representative mechanical and structural cues to the cultured cells. Besides conventional photolithographic techniques, various methods with new manipulable and biocompatible polymers have been employed for the fabrication of micro- and nanotopographic substrates to further advance cellular maturation.13, 22, 98-101 Further advancement of these technologies toward more biologically relevant and functionally competent engineered tissues is dependent on main stream adoption and widespread application. With current interest in these technologies blooming, it is envisioned that engineered solutions to tissue replacement and drug development problems will become a reality in the near future. As discussed in this review, engineered 3-D tissue constructs capable of mimicking complex tissue physiology and functionalities have amazing potential for use as tissue physiology or disease pathology models. However, bioengineered 3-D models require large numbers of cells integrated into complex configurations. Furthermore, specific extracellular components or natural scaffolds used in the synthesis of these models are often not compatible with the generation of standardized microfluidics-based or microarray-based high-throughput systems for drug discovery or toxicity testing. Critically, single organ models fail to recreate the complexity of living systems since they do not effectively mimic tissue-tissue communication and cross-talk, severely limiting their capacity to effectively predict compound action in vivo. In order to produce a more holistic view of human drug responses, next generation tissue culture platforms will therefore need to support the linkage of arrays of individual engineered tissue models or “organs-on-chips” to create more predictive “body-on-a-chip” platforms. Recent studies using organ-on-a-chip technologies highlight the potential to use such systems to evaluate the effects of toxic metabolites or physiologic waste materials produced from various organ systems on the specific responses of cultured tissue models, providing a more predictive, systemic approach to drug toxicity assessment in vitro.102-105 For example, current investigations into effective modeling of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the system of organs responsible for ingestion, digestion and excretion of food, suffer from a lack of understanding of the complex interactions between cells, tissues and gastrointestinal organs in health and disease.106-108 A unique way of coping with this explosion in complexity is mathematical and computational modeling; providing a computational framework for multilevel simulation of the human gastrointestinal anatomy and physiology. Consequently, it is believed that integrated high-throughput tissue engineering techniques, based on effective computational modeling of human systems, will produce a greater level of understanding of GI tract functionality facilitated by motility, secretion and absorption correlated with other organ functions. The introduction of better modeling techniques should improve the accuracy and efficiency of clinical treatments, which could result in reduced cost for diagnosis and effective treatment. Hence, the next wave of tools for developing more predictive preclinical drug discovery protocols will require a combination of computational modeling, and multi-organ tissue engineering integrated with high-throughput screening modalities. Attempts to generate such advanced preclinical platforms are currently underway and will likely lead to cheaper, more streamlined, and effective drug development protocols in the near future.

Acknowledgements

D.H. Kim gratefully acknowledges the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Washington for the new faculty startup fund. This work was also supported by a Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) Research Grant (MDA 255907) (D.-H.K.), an American Heart Association (AHA) Scientist Development Grant (13SDG14560076) (D.-H.K.), the Washington State Life Science Discovery Fund (D.-H.K.), and NIH R21 AR064395 (D.-H. Kim). S. Kwon is partly supported by Institute for Basic Science (IBS) and the Pioneer Research Center Program (NRF-2012-0009555). K. Nam is also partly supported by the Korea Basic Science Institute Grant D34500.

References

- 1.Mc Kim JM., Jr. Building a tiered approach to in vitro predictive toxicity screening: A focus on assays with in vivo relevance. Combinatorial Chemistry & HTS. 2010;13:188–206. doi: 10.2174/138620710790596736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.May MS, Wardell WM, Lasagna L. New drug development during after a period of regulatory change: Clinical research activity of major United States pharmaceutical firms, 1958 to 1979. Clinical Pharmacology Therapeutics. 1983;33:691–700. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eschenhagen T, Zimmermann WH. Engineering myocardial tissue. Circ Res. 2005;97:1220–1231. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196562.73231.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers CD, Bernard C, Iburg KM, Inoue M, Ma Fat D, Shibuya K, Stein C, Tomijima N, Xu H. Global burden of disease: Data sources, methods and results. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boudou T, Legant WR, Mu A, Borochin MA, Thavandiran N, Radisic M, Zandstra PW, Epstein JA, Margulies KB, Chen CS. A microfabricated platform to measure and manipulate the mechanics of engineered cardiac tissue. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:910–919. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legant WR, Pathak A, Yang MT, Deshpande VS, McMeeking RM, Chen CS. Microfabricated tissue gauges to measure and manipulate forces from 3D microtissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10097–10102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900174106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berthiaume F, Maguire TJ, Yarmush ML. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: history, progress, and challenges. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2011;2:403–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansbridge JN. Tissue-engineered skin substitutes in regenerative medicine. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009;20:563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;132:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Michniak-Kohn BB. Tissue engineered human tissue equivalents. Pharmaceutics. 2012;4:26–41. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics4010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karande P, Mitragotril S. High throughput screening of transdermal formulations. Pharmaceutical Research. 2002;19:655. doi: 10.1023/a:1015362230726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan DC, Mirmalek-Sani S–H, Deegan DB, Baptista PM, Aboushwareb T, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Decellularization methods of porcine kidneys for whole organ engineering using a high-throughput system. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7756–7764. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim P, Yuan A, Nam K-H, Jiao A, Kim DH. Fabrication of poly(ethylene glycol): gelatin methacrylate composite nanostructures with tunable stiffness and degradation for vascular tissue engineeing. Biofabrication. 2014;6:024112. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/2/024112. (12pp) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deckers MML, Van Bezooijen RL, Van Der Horst G, Hoogendam J, Van Der Bent C, Papapoulos SE, LoWik CWM. Bone morphogenetic proteins stimulate angiogenesis through osteoblast-derived vascular endothelial growth factor A. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1545–1553. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HS, et al. Assignment1 of the human basic fibroblast growth factor gene FGF2 to chromosome 4 band q26 by radiation hybrid mapping. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1998;83(1-2):73. doi: 10.1159/000015129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors. the FASEB Journal. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K, Silva EA, Mooney DJ. Growth factor delivery-based tissue engineering: General approaches and a review of recent developments. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2011;8:153–170. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seliktar D, Nerem RM, Galis ZS. Mechanical strain-stimulated remodeling of tissue-engineered blood vessel consruct. Tissue Engineering. 2003;9:657–666. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez EW, Chen QK, Gjorevski N, Nelson CM. Tissue geometry patterns epithelial-mesenchymal transition via intercellular mechanotransduction. J. Cell Biochem. 2010;110:44–51. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baguneid M, Murray D, Salacinski HJ, Fuller B, Hamilton G, Walker M, Seifalian AM. Shear-stress preconditioning and tissue-engineering-based paradigms for generating arterial substitutes. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2004;39:151–157. doi: 10.1042/BA20030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeatts AB, Fisher JP. Bone tissue engineering bioreactors: dynamic culture and the influence of shear stress. Bone. 2011;48:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim DH, Provensano PP, Smith CL, Levchenko A. Matrix nanotopography as a regulator of cell function. JCB. 2012;197:351–360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MY, Kwon KW, Jung H, Kim HN, Suh KY, Kim K, Kim K–S. Directed diffenentiation of human embryonic stem cells into selective neurons on nanoscale ridge/groove pattern arrays. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4360–4366. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Astashkina AI, Mann BK, Prestwich GD, Grainger DW. A 3-D organoid kidney culture model engineered for high-throughput nephrotoxicity assays. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4700–4711. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pathak A, Kumar S. Transforming potential and matrix stiffness co-regulate confinement sensitivity of tumor cell migration. Integr. Biolo. 2013;5:1067–1075. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40017d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patra C, Ricciardi F, Engel FB. The functional properties of nephronectin: An adhesion molecule for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4327–4335. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akins RE, Boyce RA, Madonna ML, Schroedl NA, Gonda SR, McLaughlin TA, Hartzell CR. Cardiac organogenesis in vitro: Reestablishment of three-dimensional tissue architecture by dissociated neonatal rat ventricular cells. Tissue Eng. 1999;5:103–108. doi: 10.1089/ten.1999.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bursac N, Papadaki M, Langer R, Eisenberg SR, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Freed LE. Three-dimensional environment promotes in vitro differentiation of cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1999;27:H433–H444. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmermann W-H, Schneiderbanger K, Schubert P, Didié M, Münzel F, Heubach JF, et al. Tissue engineering of a differentiated cardiac muscle construct. Circulation Research. 2002;90:223–230. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoerstrup SP, Zund G, Schnell AM, Kolb SA, Visjager JF, Schoeberlein A, Turina M. Optimized growth conditions for tissue engineering of human cardiovascular structures. Int J Artif Organs. 2000;23:817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirt MN, Boeddinghaus JB, Mitchell A, Schaaf S, Bornchen C, Muller C, Schulz H, Hubner N, Stenzig J, Stoehr A, et al. Functional improvement and maturation of rat and human engineered heart tissue by chronic electrical stimulation. J. Mole. Cell. Cardiology. 2014;74:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bian W, Badie N, Himel HD, IV, Bursac N. Robust T-tubulation and maturation of cardiomyocytes using tissue-engineered epicardial mimetics. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3819–3828. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeuchi R, Kuruma Y, Sekine H, Dobashi I, Yamato M, Umezu M, Shimizu T, Okano T. In vivo vascularization of cell sheets provided better long-term tissue survival then injection of cell suspension. J. Tissue Eng. and Regen. Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/term.1854. DOI: 10.1002/term.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang G, Nakamura Y, Wang X, Hu Q, Suggs LJ, Zhang J. Controlled release of stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha in situ increases C-kit+ cell homing to the infarcted heart. Tissue Engineering. 2007;13:2063–2071. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao J, Liu J, Gao Y, Wang C, et al. A myocardial patch made of collagen membranes loaded with collagen-binding human cascular endothelial growth factor accelerates healing of the injured rabbit heart. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2011;17:2739–2747. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burridge PW, Anderson D, Priddle H, MunOz MDB, et al. Improved human embryonic stem cell embryoid body homogeneity and cardiomyocyte differentiation from a novel V-96 plate aggregation system highlights interline variability. STEM CELLS. 2007;25:929–938. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chong JJ, Yang X, Don CW, Minami E, Liu YW, Weyers JJ, Mahoney WM, Van Biber B, et al. Human embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-humna primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510:273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myers FB, Silver FS, Zhuge Y, Beygui RE, Zarins CK, Lee LP, Abilez OJ. Robust pluripotent stem cell expansion and cardiomyocyte differentiation via geometric patterning. Integr. Biol. 2013;5:1495–1506. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20191g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim SY, Sivakumaran P, Crombie DE, Dusting GJ, Pébay A, Dilley RJ. Trichostantin A enhances differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells to cardiogenic cells for cardiac tissue engineering. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;9:715–25. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G, McCain ML, Yang L, A H, Pasoqualini FS, Agarwal A, Yuan H, Jiang D, et al. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat Med. 2014:616–623. doi: 10.1038/nm.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu T–Y, Lin B, Kim J, Sullivan M, Tobita K, Salama G, Yang L. Repopulation of decellularized mouse heart with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiovascular progenitor cells. Nature Comm. 2013;4:3307. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isayama N, Matsumura G, Sato H, Matsuda S, Yamazak K. Histological maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells in in situ tissue-engineered vasculature. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3589–3595. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lueders C, Sodian R, Shakibaei M, Hetzer R. Short-term culture of human neonatal myofibroblasts seeded using a novel three-dimensional rotary seeding device. ASAIO J. 2006;52:310–314. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000217792.45523.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Twardowski RL, Black LD. Cardiac fibroblasts support endothelial cell proliferation and sprout formation but not the development of multicellular sprouts in a fibrin gel co-culture model. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2014;42:1074–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-0971-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zong X, Bien H, Chung CY, Yin L, Fang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B, Entcheva E. Electrospun fine-textured scaffolds for heart tissue constructs. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5330–5338. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen H, Cornwell J, Zhang H, Lim T, Resurreccion R, Port T, Rosengarten G, Nordon RE. Cardiac-like flow generator for long-term imaging of endothelial cell responses to circulatory pulsatile flow at microscale. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:2999–3007. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50123j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tandon N, Taubman A, Cimetta E, Saccenti L, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Portable bioreactor for perfusion and electrical stimulation of engineered cardiac tissue. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2013;2013:6219–23. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2013.6610974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macadangdang J, Jiao A, Carson D, Lee HJ, Fugate JA, Pabon LM, Regnier M, Murry C, Kim DH. Capillary force lithography for cardiac tissue engineering. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2014:e50039. doi: 10.3791/50039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim DH, Lipke E, Kim P, Cheong R, Edmonds S, Delannoy M, Suh KY, Tung L, Levchenko A. Nanoscale cues regulate the structure and function of macroscopic cardiac tissue constructs. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences USA. 2010;107:565–570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906504107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim DH, Kshitiz, Smith RR, Kim P, Ahn EH, Kim HN, Marban E, Suh KY, Levchenko A. Nanopatterned cardiac cell patches promote stem cell niche formation and myocardial regeneration. Integrative Biology. 2012;4:1019–1033. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20067h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hansen A, Eder A, Bönstrup M, Flato M, Mewe M, Schaaf S, Aksehirlioglu B, Schwörer A, Uebeler J, Eschenhagen T. Development of a drug screening platform based on engineered heart tissue. Circ. Res. 2010;107:35–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirt MN, Hansen A, Eschenhagen T. Cardiac tissue engineering: state of the art. Circ. Res. 2014;114:354–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cosgrove BD, Sacco A, Gilbert PM, Blau HM. A home away from home: challenges and opportunities in engineering in vitro muscle satellite cell niches. Differentiation. 2009;78:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ni P, Fu S, Fan M, Guo G, Shi S, Peng J, Luo F, Qian Z. Preparation of poly(ethylene glycol)/polylactide hybrid fibrous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2011;6:3065–3075. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S25297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kostrominova TY, Calve S, Arruda EM, Larkin L. Ultrastructure of myotendinous junctions in tendon-skeletal muscle constructs engineered in vitro. Histol Histopathol. 2009;5:541–550. doi: 10.14670/hh-24.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grace Chao PH, Hsu HY, Tseng HY. Electrospun microcrimped fibers with nonlinear mechanical properties enhance ligament fibroblast phenotype. Biofabrication. 2014;3:035008. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/3/035008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeong CG, Francisco AT, Niu Z, Mancino RL, Craig SL, Setton LA. Screening of hyaluronic acid-poly(ethylene glycol) composite hydrogels to support intervertebral disc cell biosynthesis using artificial neural network analysis. Acta Biomaterialia. 2014;10:3421–3430. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vandenburgh H. High-content drug screening with engineered musculoskeletal tissues. Tissue Eng. 2010;16:55–64. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khodabukus A, Baar K. Regulating fibrinolysis to engineer skeletal muscle from the C2C12 cell line. Tissue Engineering Part C. 2009;3:501–511. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2008.0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Juhas M, Engelmayr GC, Fontanella AN, Palmer GM, Bursac N. Biomimetic engineered muscle with capacity for vascular integration and functional maturation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;15:5508–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402723111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hwang Y, Suk S, Lin S, Tierney M, Du B, Seo T, Mitchell A, Sacco A, Varghese S. Directed in vitro myogenesis of human embryonic stem cells and their in vivo engraftment. PLoS One. 2013;8:72023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Butler DL, Lewis JL, Frank CB, Banes AJ, Caplan AI, De Deyne PG, Dowling MA, Fleming BC, Glowacki J, et al. Evaluation criteria for musculoskeletal and craniofacial tissue engineering constructs: A conference report. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2008;14:2089–104. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Butler DL, Juncosa-Melvin N, Boivin GP, Galloway MT, Shearn JT, Gooch C, Awad H. Functional Tissue Engineering for Tendon Repair: A multidisciplinary strategy using mesenchymal stem cells, bioscaffolds, and mechanical stimulation. J. Ortho. Res. 2008;26:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Powell CA, Smiley BL, Mills J, Vandenburgh HH. Mechanical stimulation improves tissue-engineered human skeletal muscle. AJP-Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1557. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00595.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin NR, Passey SL, Player DJ, Khodabukus A, Ferguson RA, Sharples AP, Mudera V, Baar K, Lewis MP. Factors affecting the structure and maturation of human tissue engineered skeletal muscle. Biomaterials. 2013;23:5759–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Langelaan ML, Boonen KJ, Rosaria-Chak KY, van der Schaft DW, Post MJ, Baaijens FP. Advanced maturation by electrical stimulation: Differences in response between C2C12 and primary muscle progenitor cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;7:529–39. doi: 10.1002/term.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thorrez L, Shansky J, Wang L, Fast L, VandenDriessche T, Chuah M, Mooney D, Vandenburgh H. Growth, differentiation, transplantation and survival of human skeletal myofibibers on biodegradable scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guex AG, Birrer DL, Fortunato G, Tevaearai HT, Giraud MN. Anisotropically oriented electrospun matrices with an imprinted periodic micropattern: a new scaffold for engineered muscle constructs. Biomed Mater. 2013;2:021001. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/8/2/021001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Napolitano AP, Dean DM, Man AJ, Youssef J, Ho DN, Rago AP, Lech MP, Morgan JR. Scaffold-free Three-dimensional Cell Culture Utilizing Micromolded Nonadhesive Hydrogels. BioTechniques. 2007;43:494–500. doi: 10.2144/000112591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eastwood M, Mudera VC, McGrouther DA, Brown RA. Effect of precise mechanical loading on fibroblast populated collagen lattices: morphological changes. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1998;1:13–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)40:1<13::AID-CM2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morimoto Y, Kato-Negishi M, Onoe H, Takeuchi S. Three-dimensional neuron-muscle constructs with neuromuscular junctions. Biomaterials. 2013;34:9413–9419. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stanton L, Sabari S, Sampaio AV, Underhill TM, Beier F. p38 MAP kinase signaling is required for hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation. Biochem. J. 2004;378:53–62. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vandenburgh H, Shansky J, Benesch-Lee F, Barbata V, Reid J, Thorrez L, Valentini R, Crawford L. Drug-screening platform based on the contractility of tissue-engineered muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:438–447. doi: 10.1002/mus.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Groeber F, Holeiter M, Hampel M, Hinderer S, Schenke-Layland K. Skin tissue engineering-in vivo and in vitro applications. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2011;128:352–366. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Topol BM, Haimes HB, Dubertret L, Bell E. Transfer of melanosomes in a skin equivalent model in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;87:642–647. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12456314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hudon V, Berthod F, Black AF, Damour O, Germain L, Auger FA. A tissue-engineered endothelialized dermis to study the modulation of angiogenic and angiostatic molecules on capillary-like tube formation in vitro. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1094–1104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bechetoille N, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Damour O, Andre V, Orly I, Perrier E. Effects of solar ultraviolet radiation on engineered human skin equivalent containing both Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2667–2679. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roggenkamp D, Kopnick S, Stab F, Wenck H, Schmelz M, Neufang G. Epidermal nerve fibers modulate keratinocyte growth via neuropeptide signaling in an innervated skin model. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1620–1628. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Badylak SF, Weiss DJ, Caplan A, Macchiarini P. Engineered whole organs and complex tissues. The Lancet. 2012;379:943–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nichols JE, Niles JA, Cortiella J. Design and development of tissue engineered lung: Progress and challenges. Organogenesis. 2009;5:57–61. doi: 10.4161/org.5.2.8564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Samadikuchaksaraei A, Cohen S, Isaac K, Rippon HJ, Polak JM, Bielby RC, et al. Derivation of distal airway epithelium from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:867–75. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cortiella J, Nichols JE, Kojima K, Bonassar LJ, Dargon P, Roy AK, et al. Tissue-engineered Lung: an in vivo and in vitro comparison of polyglycolic acid and pluronic F-127 hydrogel/somatic lung progenitor cell constructs to support tissue growth. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1213–1225. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wong AP, Keating A, Lu WY, Duchesneau P, Wang X, Sacher A, et al. Identification of a bone marrow-derived epithelial-like population capable of repopulating injured mouse airway epithelium. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:336–348. doi: 10.1172/JCI36882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Banerjee ER, Laflamme MA, Papayannopoulou T, Kahn M, Murry CE, Henderson WR., Jr. Human embryonic stem cells differentiated to lung lineage-specific cells ameliorate pulmonary fibrosis in a Xenograft Transplant Mouse Model. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nichols JE, Cortiella J. Engineering of a complex organ: Progress toward development of a tissue-engineered lung. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008;5:723–30. doi: 10.1513/pats.200802-022AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petersen TH, Calle EA, Zhao L, Lee EJ, Gui L, Raredon MB, Gavrilov K, Yi T, Zhuang ZW, Breuer C, Herzog E, Laura E, Niklason LE. Tissue engineered lungs for in vivo implantation. Science. 2010;329:538–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1189345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]