Abstract

BACKGROUND

The objectives of this study were to confirm whether racial disparity exists with regard to outcome between black women and white women with ovarian cancer and to identify factors associated with the administration of adjuvant treatment that had an impact on survival.

METHODS

A retrospective review of 97 black women and 1392 white women with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage III/IV ovarian carcinoma was performed. All patients received paclitaxel combined with cisplatin while participating in 1 of 7 Gynecologic Oncology Group clinical trials. The treatment parameters that were reviewed included relative dose, relative time, and relative dose intensity. The treatment parameters and outcomes were compared between black patients and white patients.

RESULTS

There were no differences in relative dose (0.90 vs 0.89), relative time (1.02 vs 0.99), or relative dose intensity (0.90 vs 0.91) received between black patients and white patients. Black women had less grade 3 and 4 leukopenia (53% vs 63%; P < .05) and gastrointestinal toxicity (10% vs 19%; P < .05) than white women. Performance status >0, age ≥70 years, and mucinous histology were associated with not completing treatment (P < .001). The median progression-free survival was 16.2 months for black patients and 16.1 months for white patients, and the median overall survival was 37.9 months and 39.7 months, respectively (P > .05 for all).

CONCLUSIONS

When they received similar treatment, there was no difference in clinical outcome between black women and white women with advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer when they received similar treatment as participants in Gynecologic Oncology Group clinical trials. Black patients may experience less severe gastrointestinal toxicity or leukopenia compared with whites when treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, chemotherapy, Gynecologic Oncology Group, racial disparity

Greater than 20,000 new cases of ovarian cancer are diagnosed annually in the United States.1 Black women have a lower incidence of ovarian cancer than white women, and the age-adjusted rates range from 13.1 per 100,000 for whites to 9.0 per 100,000 for blacks.2 Although improvements in contemporary management of ovarian cancer (to include optimal surgical cytoreduction and more effective adjuvant chemotherapy) have accompanied a decline in cancer-related mortality over the past 30 years, survival does not appear to have improved for all racial groups.1,3,4 Despite the over-whelming, significant improvements in 2-year and 5-year survival noted among white women over the past 3 decades, there has not been a similar improvement in survival among black women over this 30-year period. The 5-year survival rate for whites diagnosed with ovarian cancer has increased from 36% to 45% whereas survival for blacks has decreased from 43% to 39%.1

Possible reasons for worse survival observed among black women with ovarian cancer compared with white women include lower rates of surgical staging and adjuvant chemotherapy administration; increased medical comorbidities; impaired access to care; and more aggressive tumors observed among black women with ovarian cancer.5-7 Of all of the above-described factors, primary cytoreductive surgery and exposure to platinum-based chemotherapy are the most important clinical factors impacting survival in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer.8 To date, studies that evaluate the impact of race on ovarian cancer survival have not taken into account the specific agents that comprise the chemotherapy regimen, nor have they detailed the application or aggressiveness of surgical debulking5-7,9,10 Chemotherapy treatment usually is treated as a dichotomized (yes vs no) variable, and most epidemiologic studies have not included adjuvant chemotherapy as an analytical variable.5-7,9-12 When it is mentioned, surgical debulking status also usually is described as a dichotomized variable (aggressive vs nonaggressive); and, when it is not mentioned, epidemiologic studies of ovarian cancer use International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage as a surrogate for surgical debulking status.5-7,9,10,12 Neither approach comments on the patient’s tumor burden after surgery, that is, whether it is optimal (≤1 cm in size for any remaining lesion) versus suboptimal (>1 cm in size for any remaining lesion), which is the variable with the most powerful impact on survival.8,13

Currently, to our knowledge, no studies of the impact of race or ethnicity on ovarian cancer survival have included dose intensity of chemotherapy in a uniformly surgically staged population. Any racial difference in chemotherapy response or survival among patients with ovarian cancer would suggest that a biologic etiology may be associated in part with the poor outcome observed among black women with advanced stage ovarian cancer. The objective of the current study was to determine whether blacks with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer who were treated as part of a prospective clinical trial experienced disparities in the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy compared with whites and whether there were any differences in survival between blacks and whites that could be influenced by differences in chemotherapy dosing parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed patient data from participants in 7 Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) randomized treatment trials of primary disease for FIGO stage III or stage IV ovarian cancer: GOG Protocols 111, 114, 132, 152, 158, 162, and 172.14-19 All eligible patients had undergone surgical staging procedures, had histologically confirmed epithelial ovarian cancer, and had a GOG performance status (PS) of 0 to 2. Patients who had received previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy for ovarian cancer were not eligible. The current analysis included only patients who received a standard intravenous cisplatin/paclitaxel regimen (paclitaxel, 135 mg/m2; cisplatin, 75 mg/m2 intravenously for 6 cycles) (Table 1). Further details regarding eligibility, treatment, and outcomes were published previously.14-19 Data on patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and course of treatment were collected from a retrospective chart review. Racial designation as black or white reflected a nonuniform collection of both self-described and investigator-reported methods. Patients from other racial groups were excluded from this analysis. All protocols received local institutional review board approval, and all patients provided written informed consent to participate in the protocols.

Table 1.

Gynecologic Oncology Group Treatment Protocols of the Study Group

| No. of Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOG Protocol |

Patient Eligibility | Treatment Arm A: Paclitaxel/Cisplatin, mg/m2 |

White | Black |

| GOG 111 | Suboptimal (>1 cm residual), stage III/IV EOC | 135/75 | 169 | 13 |

| GOG 114 | Optimal (<1 cm residual), stage III EOC | 135/75 | 202 | 16 |

| GOG 132 | Suboptimal (>1 cm residual), stage III/IV EOC | 135/75 | 178 | 14 |

| GOG 152 | Suboptimal (>1 cm residual), stage III EOC | 135/75 | 183 | 14 |

| GOG 158 | Optimal (<1 cm residual), stage III EOC | 135/75 | 353 | 25 |

| GOG 162 | Suboptimal (>1 cm residual), stage III/IV EOC/PSPC | 135/75 | 120 | 11 |

| GOG 172 | Optimal (<1 cm residual), stage III EOC/PSPC | 135/75 | 187 | 4 |

GOG indicates Gynecologic Oncology Group; EOC: epithelial ovarian cancer; PSPC: primary serous peritoneal carcinoma.

Several parameters of chemotherapy treatment were evaluated. Relative dose (RD) was defined as the ratio of actual to expected dose of chemotherapy in standard chemotherapy regimens. This was calculated for both paclitaxel and cisplatin, separately for each cycle. The relative time (RT) was defined as the ratio of actual to expected duration of chemotherapy. RT was calculated for 6 cycles, and the expected duration of time on chemotherapy was 126 days (21 days [ie, chemotherapy every 3 weeks] × 6 [ie, total cycles]). The relative dose intensity (RDI) was defined as the ratio of RD to RT. Dose adjustments for advanced age, previous radiation therapy, or body surface area (BSA) >2 mg/m2 were not considered when calculating the expected dose of chemotherapy for each treatment cycle; and these adjustments were considered dose reductions, because they differed from the standard dose of chemotherapy. The completion of 6 cycles of chemotherapy was defined as treatment completion, because this was the proposed number of cycles in the 7 GOG studies that were included in our analysis and was the accepted therapy for epithelial ovarian cancer at the time of study accrual. The average RD, RT, or RDI calculated based on cisplatin and paclitaxel was used as a summarized parameter of the combined doublet regimen, and a ratio <1.0 indicated that the patient received less intense chemotherapy than was planned.

The baseline PS before the start of chemotherapy was graded according to GOG criteria as follows: 0, fully ambulatory with no restrictions; 1, restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to perform light work; and 2, ambulatory and capable of self-care but unable to perform any work activities. The time at risk for disease progression or death was measured from the date of treatment randomization. Overall survival (OS) was measured to the date of death from any cause, and progression-free survival (PFS) was measured to the date of disease recurrence or death. Adverse effects were graded according to GOG Common Toxicity Criteria.

Statistical Analysis

The mean RD, RT, and RDI between blacks and whites were compared using the Student t test. The number of treatment cycles, cause of treatment incompletion, and causes of toxicity were compared by using Pearson chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests. The factors associated with treatment incompletion were identified using a logistic regression model. Associations of RD, RT, or RDI with survival were estimated using a Cox regression model that was adjusted for established prognostic factors (age, PS, stage/debulking status, tumor grade, histology, and race). The interaction between race and treatment parameters also was assessed. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative probability of PFS or OS. Because patients who had disease progression, poor quality of life, or other unknown adverse factors were more likely to stop treatment to avoid the ‘‘outcome to cause’’ bias, the survival analysis on RD, RT, and RDI was restricted to patients who completed all 6 cycles of chemotherapy, whereas all other analyses were done based on all patients. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System software (SAS version 9.1; SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In total, 1392 white women and 97 black women with FIGO stage III or IV epithelial ovarian cancer were assigned to receive paclitaxel and cisplatin chemotherapy (Table 2). Generally, there were no significant differences in patient characteristics between white patients and black patients, although no clear cell tumors were observed among the black women in this study population (Table 2). Most patients (87%) completed all 6 cycles of chemotherapy required by the protocol, and there was no difference in treatment parameters between white patients and black patients (Table 3). The average RD was 0.89, the average RT was 0.99, and the average RDI was 0.91. Ninety-five percent of patients reported at least 1 grade 3 or 4 adverse effect, and there was no difference in this rate between white patients and black patients (95% vs 92%) (Table 4). However, there was evidence of less leukopenia (53% vs 63%) and less gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity (10% vs 19%) among black patients compared with white patients, respectively (P < .04). The results were consistent when the analysis was adjusted for age, PS, and RD. Three factors were identified as independently predictive of treatment incompletion (Table 5): Patients aged ≥.70 years with abnormal PS or with a mucinous cell type were more likely to be unable to complete the required treatment cycles. Race was not associated with treatment incompletion.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics by Race

| Percentage of Patients |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | White, n=1392 |

Black, n=97 |

P * |

| Age, y | .148 | ||

| <50 | 26.9 | 37.1 | |

| 50-59 | 29 | 21.7 | |

| 60-69 | 29.5 | 27.8 | |

| ≥70 | 14.7 | 13.4 | |

| Median (range) | 58.2 (16-86.5) | 55.5 (20.9-80.5) | |

| GOG performance status | .069 | ||

| 0 | 40 | 30.9 | |

| 1 | 49.7 | 52.6 | |

| 2 | 10.3 | 16.5 | |

| Stage/debulking | .482 | ||

| III, microscopic | 19 | 19.6 | |

| III, optimal | 34.3 | 26.8 | |

| III, suboptimal | 31.3 | 36.1 | |

| IV | 15.5 | 17.5 | |

| Tumor grade | .102 | ||

| 1 | 8.7 | 11.3 | |

| 2 | 36.9 | 45.4 | |

| 3 Or not graded | 54.5 | 43.3 | |

| Histology | .052 | ||

| Serous | 72.7 | 77.3 | |

| Endometrioid | 8.6 | 7.2 | |

| Mucinous | 1.8 | 5.2 | |

| Clear cell | 3.2 | 0 | |

| Other | 13.7 | 10.3 | |

GOG indicates Gynecologic Oncology Group.

The Pearson chi-square test was used to compare the difference in proportion between the 2 groups.

Table 3.

Treatment Parameters by Race

| Treatment Parameter | White, n=1392 | Black, n=97 | P * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative dose† | .730 | ||

| Mean±SD | 0.89±0.21 | 0.90±0.19 | |

| Median (25th-75th percentile) | 0.97 (0.90-1.00) | 0.96 (0.89-1.00) | |

| Relative time† | .446 | ||

| Mean±SD | 0.99±0.28 | 1.02±0.36 | |

| Median (25th-75th percentile) | 1.01 (1.00-1.06) | 1.02 (1.00-1.08) | |

| Relative dose intensity§ | .510 | ||

| Mean±SD | 0.91±0.15 | 0.90±0.12 | |

| Median (25th-75th percentile) | 0.94 (0.86-0.99) | 0.94 (0.86-0.98) | |

| No. of treatment cycles, % | .874 | ||

| 0 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| 1 | 3.5 | 3.1 | |

| 2 | 2.3 | 1 | |

| 3 | 2.4 | 3.1 | |

| 4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | |

| 5 | 2.7 | 4.1 | |

| 6 | 87.1 | 86.6 |

SD indicates standard deviation.

The Student t test was used to compare difference between the 2 groups.

The ratio of the actual dose to the expected dose of chemotherapy.

The ratio of the actual duration to the expected duration of chemotherapy.

The relative dose/relative time.

Table 4.

Treatment-Related Adverse Effects by Race

| Percentage of Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Effect | White, n=1392 | Black, n=97 | P * |

| Grade 3 or 4 | |||

| Leukopenia | 62.6 | 52.6 | .048 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4.2 | 3.1 | .585 |

| Neutropenia | 90.2 | 86.6 | .249 |

| Anemia† | 6.9 | 11.5 | .217 |

| Gastrointestinal | 19.2 | 10.3 | .030 |

| Genitourinary | 1.4 | 1 | .743 |

| Neurologic | 7.2 | 6.2 | .712 |

| Cardiovascular | 3.1 | 1 | .247 |

| Any grade 3 or 4 | 95 | 91.8 | .169 |

Pearson chi-square or Fisher exact methods were used to compare the difference in proportions between 2 groups.

Data were available for 650 white patients and 52 black patients.

Table 5.

Factors Associated With Treatment Incompletion (N=1489)

| Characteristic | Incompletion, % |

OR (95% CI) | P * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | |||

| <50 | 10 | Referent | |

| 50-59 | 10.6 | 1.11 (0.70-1.75) | .651 |

| 60-69 | 11.7 | 1.21 (0.77-1.89) | .412 |

| ≥70 | 25.2 | 2.94 (1.85-4.66) | <.001 |

| Performance status | |||

| 0 | 9.2 | Referent | |

| 1 | 13.9 | 1.48 (1.03-2.12) | .033 |

| 2 | 22 | 2.59 (1.58-4.25) | <.001 |

| Stage/debulking | |||

| III, microscopic | 12.7 | Referent | |

| III, optimal | 14.1 | 1.22 (0.78-1.91) | .388 |

| III, suboptimal | 9.4 | 0.69 (0.43-1.13) | .138 |

| IV | 17.7 | 1.29 (0.78-2.15) | .324 |

| Histology | |||

| Serous | 13.1 | Referent | |

| Endometrioid | 9.5 | 0.65 (0.35-1.23) | .187 |

| Mucinous | 33.3 | 4.05 (1.78-9.22) | <.001 |

| Clear cell | 20.5 | 1.84 (0.84-4.03) | .127 |

| Other | 9.5 | 0.68 (0.40-1.14) | .140 |

| Race | |||

| White | 12.9 | Referent | |

| Black | 13.4 | 0.96 | .899 |

OR indicates odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

ORs were estimated by using a logistic regression model adjusted for covariates.

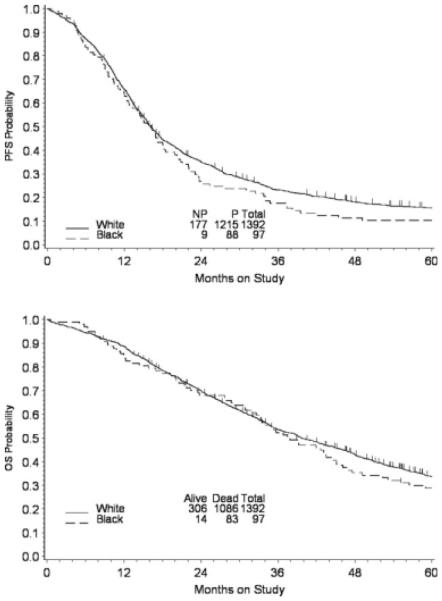

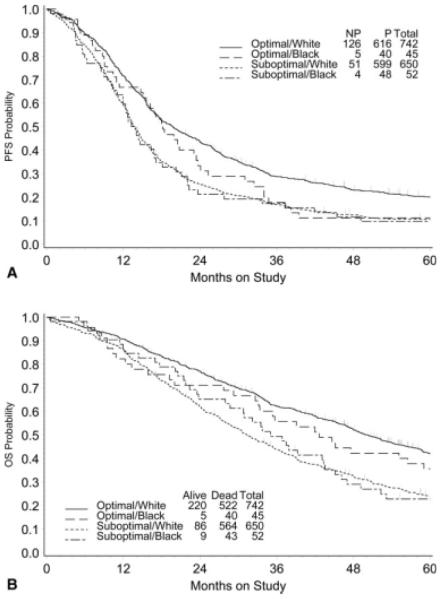

The survival of patients with advanced ovarian cancer in these trials was not affected by race. There was no difference in PFS by race (P = .223), and the median PFS was 16.2 months for blacks versus 16.1 months for whites (Fig. 1, top). Adjusted for age, PS, stage, debulking status, and histology, the hazard ratio (HR) (black vs white) for disease progression was 1.12 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90-1.40). The median OS was 37.9 months and 39.7 months for black patients and white patients, respectively (P = .132), and the adjusted HR for death was 1.19 (95% CI, 0.95-1.49) (Fig. 1, bottom). Although the patients who achieved optimal debulking status had a better clinical outcome than the patients who achieved suboptimal debulking status, there is no evidence that white patients and black patients differed significantly in terms of PFS (Fig. 2, top) or OS (Fig. 2, bottom) when the analysis was stratified for debulking status. For those patients who died, 91% died of recurrent cancer, and no difference in cancer-related death rates were reported between white women and black women (91% vs 94%). Neither RD, nor RT, nor RDI was associated with PFS or OS (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of (Top) progression-free survival (PFS) and (Bottom) overall survival (OS) by race. P indicates progression; NP, no progression.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of (Top) progression-free survival (PFS) and (Bottom) overall survival (OS) by race and debulking status. P indicates disease progression; NP, no disease progression.

DISCUSSION

Previous population-based studies of women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer have suggested that differences in surgery can lead to differences in outcome. The extent of cytoreductive surgery has been recognized for more than 20 years as an important factor in ovarian cancer survival.8 Prognosis usually depends on the size of residual disease, and median survival is related inversely to the size of residual tumor. The observed median survival was 36 months for patients who had <2 cm residual tumor and 16 months for patients who had >2 cm residual tumor.8,20 Specifically for patients who had FIGO stage III disease, the median survival was 71.9 months for those with microscopic residual tumor, 42.4 months for those with <1 cm residual tumor, and 35 months for those with >1 cm residual tumor.13 Data from the current study indicate that the rates of microscopically debulked patients were similar between the 2 racial groups, suggesting that these patients were equivalent from a surgical cytoreductive standpoint (Table 2). In a recently published evaluation of the effect of maximal surgical cytoreduction on platinum resistance at a single institution, those patients who were left with <1 cm residual tumor were more likely to obtain a complete response after initial platinum-based chemotherapy, experienced less platinum resistance, and had improved PFS and OS compared with patients who had >1 cm residual tumor.21 Evaluation of the aggressiveness of surgical effort and inclusion of this variable in the multivariate analysis of survival in the current study demonstrated that there was no difference in surgical effort or outcome between blacks and whites who were treated as a part of a prospective clinical trial, eliminating this variable as a factor that contributed to any observed racial disparity in response, toxicity or survival.

Because the population in the current study was homogenous with regard to residual tumor volume and tumor grade, in the current study, we were able to assess accurately the effect of race and dose intensity on survival in women with advanced ovarian cancer. The majority of studies evaluating the impact of race on ovarian cancer survival are epidemiologic in nature and do not take into account differences in the chemotherapy agents received.5,6,11,22 The studies that have examined the impact of chemotherapy on disparate ethnic and racial survival outcomes reported chemotherapy treatment merely as a dichotomized variable.7,10 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database evaluations consistently have revealed a survival disadvantage for blacks.5,9,11 The decreased 5-year survival observed for blacks was similar in these SEER studies, with the median survival for blacks ranging from 16 months to 22 months compared with 23 months to 32 months for whites.5,9,11 Although none of the studies specifically addressed the impact of chemotherapy on survival, the authors attributed the observed discrepancy in survival to older age at diagnosis, higher grade of tumor, and lack of surgical debulking procedures to include lymphadenectomy.

A population-based study of cases in the National Cancer Data Base evaluated chemotherapy as a dichotomized variable and reported that blacks with advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer were less likely to receive the standard combination of surgery and chemotherapy than whites (61% vs 70%).7 Blacks more frequently underwent surgery alone for stage I or II disease, (59% vs 47%) and received chemotherapy alone for stage III or IV disease (19% versus 17%). Overall, blacks were twice as likely as whites not to receive appropriate treatment. Although white patients with stage III disease had a 29% 5-year survival rate, black patient only had an 18% survival rate.7 The authors concluded that blacks received less aggressive treatment and subsequently had a lower survival rate. An evaluation of adherence to published recommendations for chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer revealed that only 66% of women aged >75 years, 81% of women with stage II disease, and 81% of black women received recommended chemotherapy.6 The reasons most frequently reported by clinicians for no chemotherapy treatment were lack of clinical indication and patient refusal. The current study supports the hypothesis that, when blacks with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer receive equal treatment compared with whites, they experience equivalent survival.

Ethnic disparities in chemotherapy toxicity also have been reported in the literature. Poor PS and differences in pharmacologic properties have been cited as possible explanations for any disparities in chemotherapy toxicity.23,24 In a study of patients with stage II and III colon cancer, investigators observed that black patients experienced less overall (defined as toxicity events grade ≥.1) GI treatment-related toxicity (ie, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and stomatitis) compared with white patients.25 In the current study, 95% of patients reported at least 1 grade 3 or 4 adverse effect, and there were no differences in severe adverse events between white patients and black patients. However, less leukopenia and less GI toxicity were observed among black patients compared with white patients even after adjustment for age, PS, and RD. Differences in toxicity result from differences in the pharmacologic clearance of certain chemotherapeutic agents among black patients and white patients. Our current results suggest that, for women with advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer, treatment with cisplatin and paclitaxel is tolerated equally among blacks and whites and that blacks experience fewer episodes of severe hematologic and GI toxicity.

This is an original report evaluating the potential contribution of differences in chemotherapy dose intensity to racial disparities in survival observed between black women and white women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. In a homogeneous population of women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer in whom surgical effort, residual disease, PS, the number of cycles received, and the percentage of treatment completion were similar among blacks and whites, we observed no differences in the RT, RD, or RDI. There was no difference in the ability of whites and blacks to tolerate cisplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy, and blacks were less likely to experience treatment-related toxicity, including leukopenia and GI toxicity, than their white counterparts. Most significantly, our study demonstrated that, when they received primary treatment for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer as part of a prospective clinical trial, black patients and white patients experienced no difference in PFS or OS. Given these results, which differ from those outcomes reported for black women versus white women in large, population-based observational studies, all minority women who are diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer should be encouraged to enroll in cooperative group clinical trials as 1 strategy to reduce and eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in survival.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology/American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Foundation and by National Cancer Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Administrative Office (CA 27469) and the Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical and Data Center (CA 37517).

Footnotes

This article is US Government work and, as such, is in the public domain in the United States of America.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman MT, Howe HL, Tung KH, et al. Incidence of ovarian cancer by race and ethnicity in the United States, 1992-1997. Cancer. 2003;97:2676–2685. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farley J, Risinger JI, Rose GS, Maxwell GL. Racial disparities in blacks with gynecologic cancers. Cancer. 2007;110:234–243. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howe HL, Tung KH, Coughlin S, Jean-Baptiste R, Hotes J. Race/ethnic variations in ovarian cancer mortality in the United States, 1992-1997. Cancer. 2003;97:2686–2693. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan JK, Zhang M, Hu JM, Shin JY, Osann K, Kapp DS. Racial disparities in surgical treatment and survival of epithelial ovarian cancer in United States. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:103–107. doi: 10.1002/jso.20932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cress RD, O’Malley CD, Leiserowitz GS, Campleman SL. Patterns of chemotherapy use for women with ovarian cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1530–1535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parham G, Phillips JL, Hicks ML, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on malignant epithelial ovarian carcinoma in African-American women. Cancer. 1997;80:816–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brun JL, Feyler A, Chene G, Saurel J, Brun G, Hocke C. Long-term results and prognostic factors in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:21–27. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuire V, Jesser CA, Whittemore AS. Survival among U.S. women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:399–403. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Malley CD, Cress RD, Campleman SL, Leiserowitz GS. Survival of Californian women with epithelial ovarian cancer, 1994-1996: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Tainsky MA, Abrams J, et al. Ethnic differences in survival among women with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1886–1893. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS, et al. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1001–1007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter WE, 3rd, Maxwell GL, Tian C, et al. Prognostic factors for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3621–3627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muggia FM, Braly PS, Brady MF, et al. Phase III randomized study of cisplatin versus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with suboptimal stage III or IV ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:106–115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194–3200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose PG, Nerenstone S, Brady MF, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for advanced ovarian carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2489–2497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spriggs DR, Brady MF, Vaccarello L, et al. Phase III randomized trial of intravenous cisplatin plus a 24- or 96-hour infusion of paclitaxel in epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4466–4471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoskins WJ, Rubin SC. Surgery in the treatment of patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 1991;18:213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EL, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Aghajanian C, Barakat RR, Chi DS. The effect of maximal surgical cytoreduction on sensitivity to platinum-taxane chemotherapy and subsequent survival in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuire V, Herrinton L, Whittemore AS. Race, epithelial ovarian cancer survival, and membership in a large health maintenance organization. Epidemiology. 2002;13:231–234. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200203000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JA. Influence of race or ethnicity on pharmacokinetics of drugs. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86:1328–1333. doi: 10.1021/js9702168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tam KF, Chan YM, Ng TY, Wong LC, Ngan HY. Ethnicity is a factor to be considered before dose planning in ovarian cancer patients to be treated with topotecan. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:135–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCollum AD, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, et al. Outcomes and toxicity in African-American and Caucasian patients in a randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1160–1167. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]