Abstract

Object

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is characterized by neovascularization, raising the question of whether angiogenic blockade may be a useful therapeutic strategy for this disease. It has been suggested, however, that, to be useful, angiogenic blockade must be persistent and at levels sufficient to overcome proangiogenic signals from tumor cells. In this report, the authors tested the hypothesis that sustained high concentrations of 2 different antiangiogenic proteins, delivered using a systemic gene therapy strategy, could inhibit the growth of established intracranial U87 human GBM xenografts in nude mice.

Methods

Mice harboring established U87 intracranial tumors received intravenous injections of adenoviral vectors encoding either the extracellular domain of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2-Fc fusion protein (Ad-VEGFR2-Fc) alone, soluble endostatin (Ad-ES) alone, a combination of Ad-VEGFR2-Fc and Ad-ES, or immunoglobulin 1-Fc (Ad-Fc) as a control.

Results

Three weeks after treatment, magnetic resonance imaging-based determination of tumor volume showed that treatment with Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, or Ad-VEGFR2-Fc in combination with Ad-ES, produced 69, 59, and 74% growth inhibition, respectively. Bioluminescent monitoring of tumor growth revealed growth inhibition in the same treatment groups to be 62, 74, and 72%, respectively. Staining with proliferating cell nuclear antigen and with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling showed reduced tumor cell proliferation and increased apoptosis in all antiangiogenic treatment groups.

Conclusions

These results suggest that systemic delivery and sustained production of endostatin and soluble VEGFR2 can slow intracranial glial tumor growth by both reducing cell proliferation and increasing tumor apoptosis. This work adds further support to the concept of using antiangiogenesis therapy for intracranial GBM.

Keywords: antiangiogenesis, endostatin, gene therapy, glioblastoma multiforme, vascular endothelial growth factor

High-grade astrocytic tumors are the most common primary tumors of the central nervous system. Despite combined multimodal treatments (surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy with oral alkylating agents such as temozolomide), the median survival time for patients with GBM is approximately 12–18 months.7,27,45,78

The identification and development of novel therapeutic strategies therefore remains an important priority in this disease. Because GBM is characterized by endothelial cell proliferation and a high degree of vascularity, it has been suggested that antiangiogenic approaches may be an especially useful adjunct to other therapies.

Use of antiangiogenic therapy for brain tumors is based on the premise that the progressively higher grade of glial tumors requires an extensive network of blood vessels.20,25,34,60,61,91 Strategies to abrogate new blood vessel formation have been explored in preclinical models of GBM and have shown some success.23,31–33,37,41,62,69,81 In tumor-induced angiogenesis of high-grade gliomas, VEGF and its cognate receptors (VEGFR1 and VEGFR2) play a major role,9,17,22,44,53,59,67,75,76,82 and this receptor–ligand interaction has been the target of several antiangiogenic strategies in preclinical brain tumor models.8,23,31,33,51,62,81 Treatment of human GBM xenografts with monoclonal antibodies specific to VEGF inhibits neovascularization.8,90 The inhibition of endogenous VEGF expression by an antisense VEGF sequence significantly reduced vascularization and tumorigenicity of high-grade glioma cell lines.15,69 In addition to inhibitors of the VEGF pathway, other tested angiogenesis inhibitors for brain tumor therapy have included interferon-α,4,18,19 angiostatin,18,35,36,50,56,58,66,83,92 and endostatin.3,6,28,38,39,52,55–57,64,65,70,77,88

Because effective antiangiogenic therapy requires both long-term and sustained therapeutic levels at the tumor site21,73 we sought to explore whether a systemic gene therapy approach, delivering a sustained dose of antiangiogenic protein via gene transfer, could demonstrate an antitumor effect against GBM grown in the intracranial compartment. In this report we show that systemic delivery of recombinant adenoviral vectors encoding either a soluble VEGFR (Ad-VEGFR2-Fc) or endostatin (Ad-ES) were efficacious in slowing GBM growth in vivo. This work lays a foundation for considering the systemic delivery of these proteins in human studies for patients with GBM.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Male Swiss–Webster nude mice 4–6 weeks old were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, and all animal work was conducted at the Animal Research Core Facility at the Harvard Institutes of Medicine in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Construction of Recombinant Adenoviruses

The E1- and E3-deleted adenoviral vectors were constructed as previously described,42 propagated on 293A cells and purified by 2 cycles of CsCl banding.14 The final products were titered using the optical absorbance method,48,49 and the results were converted to pfu/ml. Viruses produced included: Ad-Fc (batch 62.42, 3.4 × 1010 pfu/ml); Ad-VEGFR2-Fc (batch 275, 1.4 × 1010 pfu/ml; batch 275.11, 1.9 × 1010 pfu/ml; and batch 275.2, 5.2 × 1010 pfu/ml); and Ad-ES (batch 55.6, 7 × 109 pfu/ml).

Cell Cultures

The human GBM cell line U87 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in minimal essential medium (Life Technologies, Inc.) supplemented with 2 mM of L-glutamine, 100 units/ml of penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Inc.). Cells were maintained in tissue culture dishes (10-cm diameter) in 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C in a humidified incubator. The U87-LuciferaseNeo (U87-LucNeo) cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Andrew Kung at Dana Farber Cancer Institute and was created by retroviral transduction with a firefly luciferase/neomycin fusion gene of the parental U87 glioma cells, followed by clonal selection.68 The U87-LucNeo cells were grown and maintained in the same conditions as the U87 cells.

Orthotopic Implantation of Tumor Cells and Adenoviral Injections

Orthotopic human GBM xenografts were established in 4–6-week-old Swiss–Webster nude mice. Animals were anesthetized using 100 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine and received a stereo-tactically guided injection of 1 × 105 U87-LucNeo cells into the left striatum (2.5 mm lateral and 0.5 mm posterior to the bregma, at a 3.5 mm intraparenchymal depth) using a Kopf stereotactic frame (David Kopf Instruments). Using an automated microinjector (Model 310, Stoelting), the cells were injected in a volume of 2 μl over a period of 5 minutes. Seven days after tumor cell injection the mice underwent imaging using a Xenogen IVIS system (Xenogen Corporation) to record luciferase-derived bioluminescent signals emitted from the engrafted tumors as previously described.12,80 Following BLI, the animals were randomized into the following treatment groups (10 animals/group) and received a single intravenous injection of 1 × 109 pfu/ml of either Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, the combination of Ad-VEGFR2-Fc and Ad-ES, or Ad-Fc (control group). On Day 35 after tumor implantation, the animals were killed and their brains were harvested for histological examination.

Determination of Transgene Expression Using ELISA

Plasma samples were obtained 3 days after treatment and once a week for 5 weeks using retroorbital puncture with heparinized capillary tubes while the mice were anesthetized. Murine plasma VEGFR2 concentrations were determined by sandwich ELISA using anti–murine VEGFR2 primary antibody (BD Pharmigen) and anti–murine immunoglobulin G2a Fc-horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) as previously described.42 Murine endostatin plasma levels were quantitated using competition ELISA (CytImmune Sciences).

Bioluminescence Imaging

Animals first underwent BLI 1 week after tumor injection, then once a week for 4 additional weeks. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and then received intraperitoneal injections of DLuciferin (Xenogen Corporation) at 300 μg/g body weight concentration. Approximately 5 minutes after D-Luciferin injection, mice were placed in the imaging chamber of the Xenogen IVIS 100 CCD system (Xenogen Corporation) and a grayscale image was acquired. Following this procedure, bioluminescence was acquired for 30–60 minutes while the peak BLI emission was recorded from each animal. Living Image software (Wavemetrics Corporation) was used for data analysis. For each animal an ROI was drawn, encompassing the cranium to calculate maximum photon efflux. Final BLI values are reported as total photon efflux emission (photons/second).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Animals underwent MR imaging prior to being killed at Week 4 after tumor injection. Tumor growth was evaluated on a 4.7-T micro-imaging system (Biospec, Bruker BioSpin, Inc.), which consists of 3-axis self-shielded magnetic field gradients, with 30 G/cm maximum gradient amplitude in all 3 channels. Gadopentetate dimeglu-mine (Magnevist, Schering) was administered intraperitoneally (0.25 mmol Gd/kg body weight), and the mice were anesthetized using 1% isoflurane (IsoFlo, Abbott Laboratories) in O2 and placed within a radio frequency coil (inner diameter 35 mm). Gadopentetate-enhanced T1- and T2-weighted images were subsequently acquired with a 1-mm slice thickness (gapless) using a conventional spin-echo pulse sequence and a fast spin echo sequence, respectively, on the entire brain. The pulse repetition times and echo times were 1000 and 10 msec for T1-weighted imaging and 2000 and 40 msec for T2-weighted imaging, respectively, with a matrix size of 128 × 128, a 3-cm field of view, and 2 averages, resulting in a total scan time of approximately 4.5 and 2.4 minutes, respectively.

Immunohistochemical Determination of VEGF, PCNA, Factor VIII, and TUNEL

Paraffin-embedded tissues were used for identification of VEGF, PCNA, Factor VIII, and TUNEL. Sections (4–6 μm thick) were mounted on positively charged Superfrost slides (Fischer Scientific Co.) and dried overnight. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene followed by treatment with a graded series of alcohol (100, 95, and 80% ethanol in distilled H2O by volume) and rehydrated in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5). Sections analyzed for PCNA were microwaved for 5 minutes for antigen retrieval.71 Sections analyzed for Factor VIII were stained in the Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. All other paraffin-embedded tissues were treated with pepsin (Biomeda) for 15 minutes at 37°C and washed with phosphate-buffered saline prior to immunohistochemical staining.86

The TUNEL assay was performed using a commercially available apoptosis detection kit with modifications as described previously. 11,74 Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed using an epifluorescence microscope equipped with narrow bandpass excitation filters mounted in a filter wheel (Ludl Electronic Products) to select for green fluorescence. Images were captured using a 3 CCD camera (Photometrics), mounted on a Zeiss universal microscope (Carl Zeiss), and analyzed using Optimas Image Analysis software (Bio-scan) installed on a Compaq computer with a Pentium chip, frame grabber, optical disk storage system, together with a Sony Mavigraph UP-D7000 digital color printer. Images were additionally processed using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems).

Quantification of Microvessel Density, PCNA, TUNEL, VEGF Absorbance, and Data Analysis

For the quantification of Factor VIII staining, 10 random fields (0.159 mm2) at a magnification of 100 were captured for each tumor, and microvessels were quantified according to the method described previously.63,85,89 Briefly, the immunostained sections were scanned, and the tumor area with the highest density of distinctly highlighted microvessels (the “hot spot”) was selected. Each stained lumen was regarded as a single countable microvessel, and if no lumen was visible, this cell was also interpreted as a single microvessel. For the quantification of the immunohistochemical reaction intensity, the absorbance of 100 VEGF-positive cells in 10 random fields (0.039 mm2) of tumor tissue at a magnification of 100 was measured using Optimas image analysis software.10,40 The VEGF cytoplasmic immunoreactivity was evaluated by computer-assisted image analysis. To quantify PCNA expression, we counted the number of positive cells in 10 random fields (0.159 mm2) at a magnification of 100. For the quantification of total TUNEL expression, the number of apoptotic events was counted in 10 random fields (0.159 mm2) at a magnification of 100.

For bioluminescent data analysis, the ROI encompassing the intracranial space was drawn using Living Image software, and the total photons per second in the ROI was recorded on a spreadsheet. In addition, the time point at which the peak photon emission was observed was also recorded. For MR imaging data analysis, transverse Gd-enhanced T1-weighted sequences were segmented by 3 investigators (O.S., C.H.B., and S.S.B.) in 3 independent settings using National Institutes of Health image software, with a conversion of 1 MR imaging pixel = 0.529 mm3; DTATA software was used for statistical analysis and graphing. Linear regression was performed on log-transformed bioluminescence and MR imaging volume data. The data were analyzed by 2 different methods: 1) using actual peak BLI values and time-to-peak measurements; or alternatively, 2) using a parabolic curve fit (MATLAB software) to the data of each mouse to determine a calculated peak BLI and time-to-peak value.

Results

Systemic Treatment of Human GBM by Adenoviral Vectors Encoding Antiangiogenic Proteins

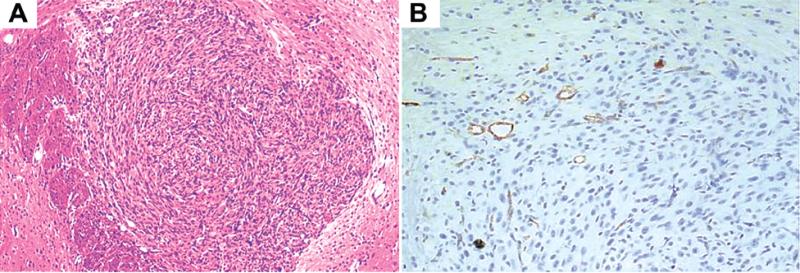

Seven days after intracranial implantation of U87-Luc-Neo GBM tumor cells, 5 mice were killed to confirm the presence of solid tumor lesions. Histological examination (Fig. 1) and BLI confirmed that the lesions were actively growing vascularized GBM. The remaining mice were then randomized into 4 treatment groups of 10 mice each and received tail-vein injections of Ad-Fc (109 pfu), Ad-VEGFR2-Fc (109 pfu), Ad-ES (109 pfu), or a combination of Ad-VEGFR2-Fc (109 pfu) and Ad-ES (109 pfu).

FIG. 1.

Photomicrographs demonstrating the vascularized tumor at initiation of treatment. Human intracranial U87 GBM tumors established in nude mice were harvested and sectioned for histological examination 1 week after injection. A: A solid 3D tumor mass is demonstrated after H & E staining. B: The subsequent paraffin-embedded section was stained with hematoxylin and Factor VIII, demonstrating numerous blood vessels within the 1-week-old tumor xenograft. Original magnification × 4 (A) and × 20 (B).

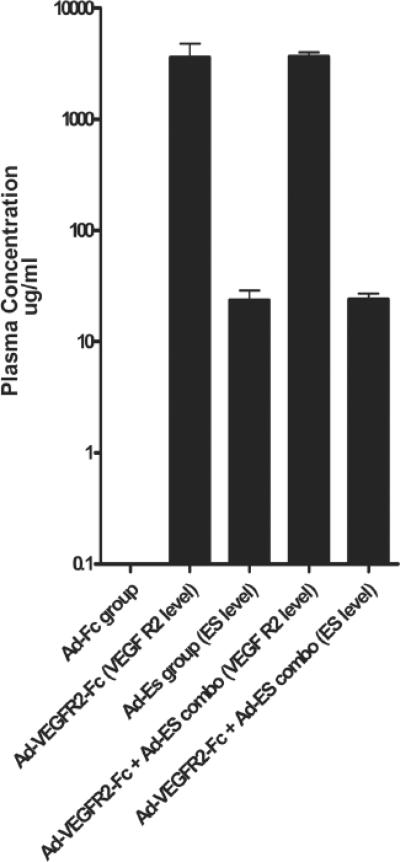

In the present study, the levels of VEGFR2-Fc and endostatin in the plasma were determined 3 and 35 days (in surviving animals) following viral injection. The average initial peak plasma level of antiangiogenic protein in each treatment group is shown in Fig. 2. Animals treated with Ad-VEGFR2-Fc alone had a mean plasma level of VEGFR2-Fc of 3.86 ± 2.8 mg/ml, which declined to an average of 0.53 mg/ml in surviving animals by Week 5 after treatment. The mean plasma level of endostatin in mice treated with Ad-ES was 22.5 ± 11.49 μg/ml, which declined to an average of 935 ng/ml in surviving animals by Week 5 after injection. In a series of repeated experiments, the therapeutic effect of Ad-VEGFR2-Fc in inhibiting established intracranial glioma growth was reached at concentrations as low as 1 mg/ml (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Bar graph showing serum levels of endostatin and soluble VEGFR2 after systemic adenoviral-based delivery. Peripheral blood was collected from all animals 3 days following adenoviral administration and plasma levels of secreted VEGFR2-Fc and endostatin proteins were quantitated using ELISA assays. On the y axis the log of concentration of the various proteins analyzed is shown in μg/ml. On the x axis the different treatment groups and the type of ELISA that is represented (in parentheses) are shown. ES = endostatin.

Tumor Growth Kinetic Calculations Based on BLI and MR Imaging

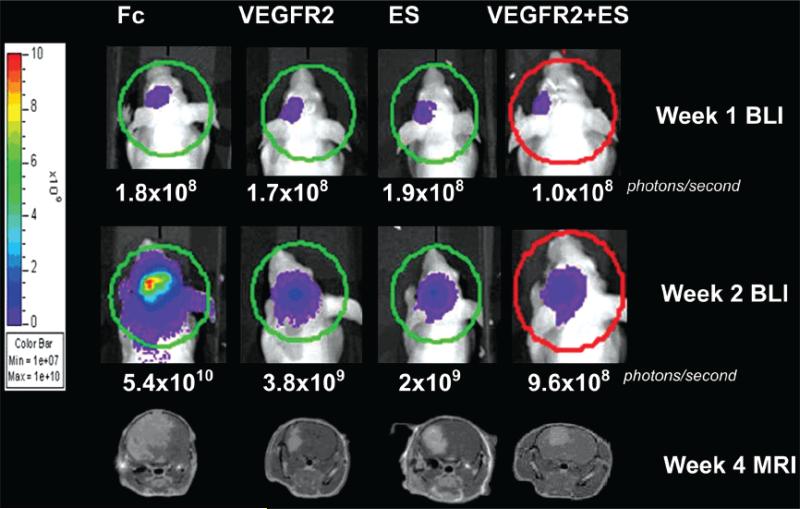

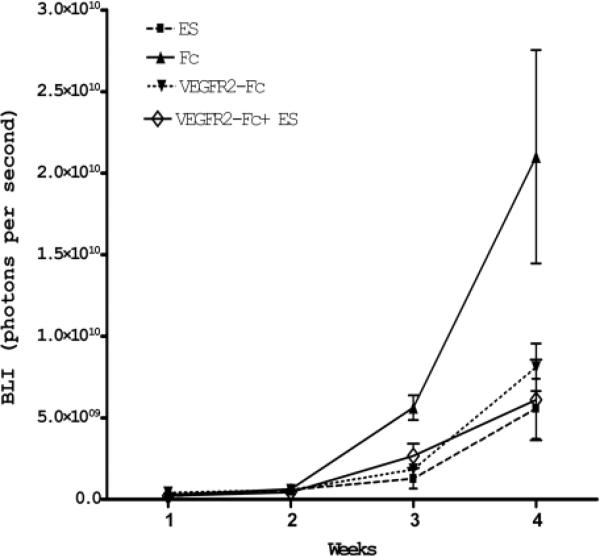

We examined tumor growth kinetics by obtaining weekly bioluminescence acquisitions from U87-LucNeo–expressing tumors as well as from MR imaging on Week 4 after tumor implantation. Figure 3 demonstrates the increase in bioluminescence from Week 1 to Week 4 for individual mice and the correlation between BLI and MR imaging at Week 4. Using this technique of dual BLI and MR imaging, we measured the therapeutic effect of adenoviral antiangiogenic therapy on intracranial tumor growth. Serial BLI measurements showed that intravenous injection of Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, or the combination of the 2 significantly inhibited intracranial tumor growth in comparison with the Ad-Fc control group (Fig. 4). Treated animals showed a slower rate of tumor growth as soon as 3 weeks after initiation of therapy, and these differences were maintained until the untreated animals were killed due to terminal neurological symptoms secondary to tumor-associated cerebral herniation. At Week 4, there was a statistically significant difference in total bioluminescence (p < 0.005, analysis of variance) between the treatment groups and the control group.

FIG. 3.

Images showing the assessment of antitumor effect using BLI and MR imaging. Representative cases from each treatment group show MR imaging sequences at Week 4 and serial bioluminescent images at Weeks 1 and 2. The ROI calculation of total photons/second was performed using Xenogen Living Image software and is represented by the colored circle outlines. Magnetic resonance imaging volumes were calculated following manual segmentation by measurement of gadolinium-enhancing areas of the tumor in serial axial sections.

FIG. 4.

Line graph showing the effects of the various treatments on intracranial tumor growth kinetics detected by serial BLI. The log of concentration (BLI) expressed in photons/second is shown on the y axis. The length of this study is shown on the x axis (4 weeks following the initiation of therapy). All treatments inhibited the aggressive growth of solid GBM tumors, with no significant differences observed between the treatment groups. This effect is first observed at Week 3, and the therapeutic window expands further by Week 4, indicating a sustained tumor static effect.

In addition, at Week 4, the solid tumor volume (as detected by MR imaging) in treated animals was significantly smaller than the tumor volume in untreated animals. Average tumor volumes (expressed as mm3) were calculated from segmented MR images: 35.9 ± 22.9 mm3 in the Ad-VEGFR2-Fc group, 47.2 ± 23.5 mm3 in the Ad-ES group, 28.9 ± 11.3 mm3 in the Ad-VEGFR2-Fc and Ad-ES combined group, and 113.1 ± 50.8 mm3 in the Ad-Fc control group (p < 0.005 for difference in means by analysis of variance; p < 0.05 for all treatment groups versus the Ad-Fc control group, pairwise t-tests; p = 0.48 for difference of means between treatment groups). All treatment groups showed statistically smaller tumors than the control group and no statistically significant differences were noted between treatment groups. The ratio of treated versus control tumor volumes (T:C ratio) on MR imaging in the Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, and Ad-VEGFR2-Fc and Ad-ES combined groups was 0.31, 0.41, and 0.26, respectively.

Comparative analysis of the tumor volume on MR imaging and bioluminescence intensity (a measure of viable tumor cells expressing luciferase) revealed a similar degree of tumor growth inhibition in the Ad-VEGFR2-Fc (BLI = 62%, MR imaging = 69%), Ad-ES (BLI = 74%, MR imaging = 59%), and the combined Ad-VEGFR2-Fc/Ad-ES (BLI = 72%, MR imaging = 74%) treatment groups.

Immunohistochemical Analysis and Microvessel Densities

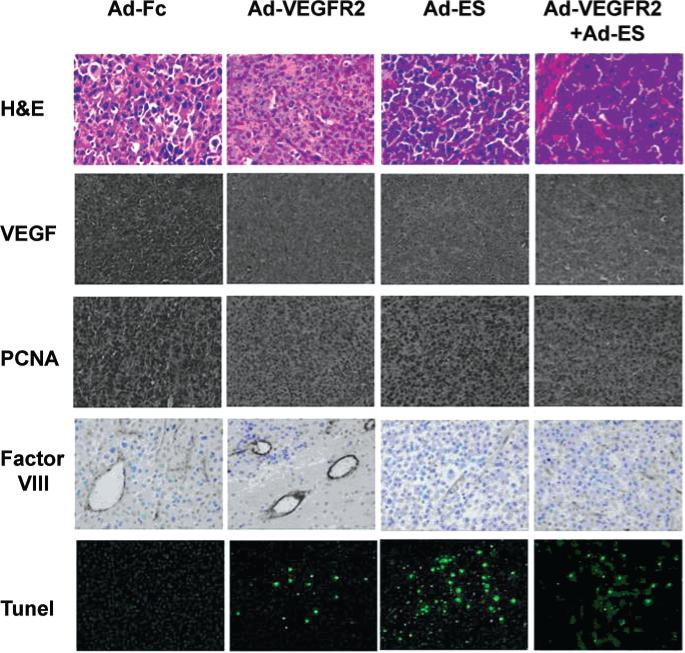

In vivo cell proliferation and apoptosis were evaluated using anti-PCNA antibodies and the TUNEL method, respectively (Fig. 5). Regardless of treatment, the number of PCNA-positive cells decreased in all treatment groups as compared with the control group, and the mean number of TUNEL-positive cells was inversely correlated with PCNA positivity (Table 1). In tumors in the control group, the mean number of TUNEL-positive cells was 3 ± 2/hpf, whereas among the treatment groups the highest count was 206 ± 18 apoptotic cells/hpf, found in tumors from mice treated with Ad-ES. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that production of VEGF by the GBM cells was significantly reduced after treatment with Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, or Ad-VEGFR2-Fc combined with Ad-ES, as compared with the Ad-Fc control; however, there was no qualitative difference observed between the different treatment groups based on immunostaining (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Photomicrographs demonstrating the results of immunohistochemical analysis of H & E, VEGF, PCNA, Factor VIII, and TUNEL staining in the 4 treatment groups. At the termination of the study at Week 4 the brains were harvested and processed for histological examination. The tissue sections were immunostained for VEGF, PCNA (the PCNA stain was used as a marker for cellular proliferation), Factor VIII (to show the presence of endothelial cells and to permit the calculation of microvessel density), and TUNEL (to show the degree of apoptosis, stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate). The highly vascularized GBM tumor is shown with Factor VIII staining. A decrease in VEGF and PCNA expression was observed in tumors from mice in all treatment groups as compared with controls. Treatment with Ad-ES significantly increased the number of TUNEL-positive tumor cells. Original magnification × 40 (top row), × 20 (all remaining rows).

TABLE 1.

Summary of results of treatment of orthotopically implanted human GBM U87 cells by adenoviral antiangiogenic therapy

| Treatment Group* | PCNA-Positive Cells† | TUNEL-Positive Cells‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Ad-Fc (control) | 600 ± 69 | 3 ± 2 |

| Ad-VEGFR2-Fc | 299 ± 54 | 42 ± 5 |

| Ad-ES | 398 ± 32 | 206 ± 18 |

| Ad-VEGFR2-Fc + Ad-ES | 289 ± 28 | 110 ± 22 |

U87 GBM cells (1 × 105) were injected into the left striatum of nude mice. Seven days later, mice were treated with a single intravenous injection of 1 × 109 pfu/ml of Ad-Fc (control), Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, or Ad-VEGFR2-Fc in combination with Ad-ES. All mice were killed at Week 4.

Mean ± standard deviation PCNA-positive cells/field determined by measuring 10 random fields (0.159 mm2) at a magnification level of 100.

Mean ± standard deviation TUNEL-positive cells/field determined by measuring 10 random fields (0.159 mm2) at a magnification level of 100.

Microvessel density, assessed using Factor VIII staining, was determined according to the method of Weidner.85 Qualitatively, the blood vessels in brain tumors from mice treated with Ad-Fc (control) were larger and more variable in size than in brain tumors from mice treated with Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, and Ad-VEGFR2-Fc combined with Ad-ES. Brain tumors in the combination treatment group of Ad-VEGFR2-Fc/Ad-ES demonstrated the smallest microvessel density in a qualitative review of the immunohistochemical results (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In this study, 2 different antiangiogenic proteins—soluble endostatin and soluble VEGFR2 extracellular domain—were systemically delivered to nude mice by adenoviral gene therapy, resulting in inhibition of growth of intracranial GBM xenografts. At Week 4, serial BLI and MR imaging of tumor volume measurements in treated and untreated animals showed that a single intravenous injection of Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, or the combination of the 2, significantly reduced BLI intensity in the tumor and decreased tumor growth in the treated animals by 64–75% as compared with the control animals injected with soluble Fc.

To better understand mechanisms of action of these antiangiogenic proteins, immunohistochemical analysis of the proangiogenic cytokine, VEGF, and analysis of microvessel density was also undertaken. A hallmark of GBM (Grade IV astrocytoma) is vascular endothelial cell proliferation and neovascularization. The neovascularization in the region of a GBM is abnormal, however, and the absolute density of new microvessels may not achieve that of the normal brain. In late stages of growth, a necrotic core often develops within the GBM, suggesting that neovascularization is not able to maintain a state of complete vascularization of the solid tumor. One study showed that the microvessel density in patients with GBM is 78% of normal brain tissue, postulated as being related to a lower O2 consumption rate of tumor cells.5 It has also been suggested that lower microvessel density in tumors may relate to increased intercapillary distance as multiple layers of tumor cells surround a blood vessel.26 In other tumor systems, it has been shown that the relative expression of angiogenic factors changes over time, with a resulting imperfect correlation between angiogenic factor expression and micro-vessel density.30 In the present study, immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 5) revealed that all tumors from treated animals continued to express VEGF at similar levels, but there was a qualitative reduction in both microvessel density and microvessel diameter in tumors from animals treated with Ad-VEGFR2-Fc, Ad-ES, and with combination Ad-VEGFR2-Fc and Ad-ES therapy, consistent with changes in blood vessel angioarchitecture according to therapy type.

Interestingly, the Ad-ES tumors were the most apoptotic as demonstrated by TUNEL assay, raising the question of whether endostatin in the concentrations achieved in this study may exhibit a direct apoptotic effect as well as indirect effects on tumor growth though antiangiogenesis. Li and colleagues46 found that adenovirus-associated virus-based delivery of endostatin had direct antitumor proapoptotic effects consistent with our findings, although they did not report serum levels of endostatin. In this report, using an adenoviral delivery system, a relatively high serum level of endostatin was obtained (in the 10s of micrograms/ml range) compared with most studies that have shown efficacy of endostatin in the 150–200 ng/ml range.16,47,84 Notably, the initial peak levels of gene expression at Week 1 obtained in these nude mice (3.86 mg/ml for VEGFR2-Fc and 22.5 μg/ml of soluble endostatin) that yielded an antitumor effect were comparable to those achieved in a prior study (2–8 mg/ml for VEGFR2-Fc and > 15 μg/ml for endostatin) that we performed involving other nonneural tumor types growing in the subcutaneous space.42 The finding in this study of growth inhibition of U87 tumors by Ad-ES differs somewhat from findings in other tumor types by Kuo and associates40 who observed only a small amount of growth inhibition in Lewis-lung-carcinoma (~ 27%) and minimal (< 12%) inhibition of PxPC3 pancreatic tumor cells. Tjin et al.84 produced serum endostatin concentrations of 1–4 μg/ml in a canine Fc/ES fusion protein after intramuscular adenovirus-associated virus delivery and did not observe an antitumor effect, yet found excellent growth inhibition at lower concentrations. These investigators suggested that a ∪-shaped efficacy curve may best explain the antitumor effects of endostatin in that model system.

In contrast to the lack of efficacy of endostatin in some tumor models, Abdollahi and colleagues1 also observed endostatin-mediated inhibition of subcutaneous U87 tumors (subcutaneous delivery of protein), both as a single therapy and synergistically with VEGF-signaling blockage using SU5416, a VEGFR2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The combined therapy with SU5416 and endostatin enhanced the antiangiogenic effects in human endothelial cells in vitro and enhanced subcutaneous tumor growth delay of human xenografts (prostate adenocarcinoma PC3, non–small-cell lung cancer A549, and GBM U87). Although we did observe an inhibition of intracranial U87 with either agent (Ad-ES or Ad-VEGFR2), we did not observe a synergistic effect of coupling endostatin with VEGF blockade as a combination therapy as has been shown in some reports.24 As of August 2005, recombinant yeast-derived endostatin is no longer used in clinical studies in the US,87 although a modified endostatin has shown efficacy in a Phase-III study in China.79 Given that VEGF blockade (Avastin) has already demonstrated efficacy in some human tumors, a gene-based blockade of the VEGF pathway is a more feasible target for the systemic gene therapy approach as described in this study.

In terms of translation of these efforts to the clinic, several limitations and unexplored issues are worth noting. First, the tumor model used (U87) tends to grow as a solid mass when engrafted (Fig. 1), whereas high-grade gliomas in general are characterized as an invasive disease. In the invasive disease scenario, a small cluster of invading glioma cells at the leading edge or distant from a solid tumor core may be able to effectively coopt the existing blood supply and be less amenable to treatment using an antiangiogenic approach. Recent data suggest that more invasive growth patterns can be achieved using human tumor cells derived from the CD133+ population,72 and it will be useful to assess the efficacy of these cells in such models. Second, the xenograft model in T-cell-deficient nude mice allowed us to have long-term transgene expression over the course of the study without repeated dosing. This model does not, however, fully capture all of the problems faced when trying to achieve long-term transgene expression in the immunocompetent host, in which cellular immunity can destroy initially infected cells and humoral antibody responses markedly inhibit the effect of repeat dosing.54 In previous work from our group, systemic intravenous delivery of first-generation adenoviral vectors in immunocompetent mice produced only transient (~ 30 days) expression with presumed immune-mediated loss of gene expression.42 The solution to this problem is multifactorial and potentially involves: 1) adoption of local intracerebral delivery of the vector (in the intracerebral peritumoral milieu); 2) the use of third generation helper-dependent adenoviral vectors that allow for longer persistence of gene expression; and 3) the use of immune modulation (such as cyclophosphamide) to reduce innate antiadenoviral responses.2,13 Immuno-modulation has been used for other immunogenic vectors such as herpes simplex viral vectors29 and may be required for adenoviral-based vectors as well.43

In addition, this study of “biological” therapy involving delivery of antiangiogenic proteins will need to be compared directly to the emerging array of small molecular inhibitors of angiogenesis. And finally, antiangiogenic therapy is generally not curative; second generation studies that test antiangiogenic therapy in combination with radiation and chemotherapy will be particularly valuable.

Conclusions

Although our results suggest that a systemic antiangiogenic therapy can be efficacious for inhibiting intracranial GBM growth, additional studies will be important to clarify the exact agents and delivery strategy needed to best achieve the antiangiogenic effect in the clinic. Further investigations are currently underway to address these additional questions. We hope these studies add further support for the future clinical use of antiangiogenic therapies for patients with GBM.

Acknowledgments

Oszkar Szentirmai, M.D., and Cheryl H. Baker, Ph.D., contributed equally to this work. Our esteemed colleague, Judah Folkman, M.D., died in January 2008.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Ad-ES

adenoviral endostatin

- BLI

bioluminescence imaging

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- MR

magnetic resonance

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- pfu

plaque-forming unit

- ROI

region of interest

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

VEGF receptor

References

- 1.Abdollahi A, Lipson KE, Sckell A, Zieher H, Klenke F, Poerschke D, et al. Combined therapy with direct and indirect angiogenesis inhibition results in enhanced antiangiogenic and antitumor effects. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8890–8898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bangari DS, Mittal SK. Current strategies and future directions for eluding adenoviral vector immunity. Curr Gene Ther. 2006;6:215–226. doi: 10.2174/156652306776359478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett FH, Scharer-Schuksz M, Wood M, Yu X, Wagner TE, Friedlander M. Intra-arterial delivery of endostatin gene to brain tumors prolongs survival and alters tumor vessel ultrastructure. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1283–1289. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belardelli F, Gresser I, Maury C, Duvillard P, Prade M, Maunoury MT. Antitumor effects of interferon in mice injected with interferon-sensitive and interferon-resistant friend leukemia cells. III. inhibition of growth and necrosis of tumors implanted subcutaneously. Int J Cancer. 1983;31:649–653. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910310518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birner P, Piribauer M, Fischer I, Gatterbauer B, Marosi C, Ambros PF, et al. Vascular patterns in glioblastoma influence clinical outcome and associate with variable expression of angiogenic proteins: evidence for distinct angiogenic subtypes. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:133–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjerkvig R, Read TA, Vajkoczy P, Aebischer P, Pralong W, Platt S, et al. Cell therapy using encapsulated cells producing endostatin. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2003;88:137–141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6090-9_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black PM. Brain tumors. Part 1. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1471–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105233242105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borgstrom P, Hillan KJ, Sriramarao P, Ferrara N. Complete inhibition of angiogenesis and growth of microtumors by anti-vascular endothelial growth factor neutralizing antibody: novel concepts of angiostatic therapy from intravital videomicroscopy. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4032–4039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouck N, Stellmach V, Hsu SC. How tumors become angiogenic. Adv Cancer Res. 1996;69:135–174. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60862-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruns CJ, Harbison MT, Kuniyasu H, Eue I, Fidler IJ. In vivo selection and characterization of metastatic variants from human pancreatic adenocarcinoma by using orthotopic implantation in nude mice. Neoplasia. 1999;1:50–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruns CJ, Solorzano CC, Harbison MT, Ozawa S, Tsan R, Fan D, et al. Blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling by a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor leads to apoptosis of endothelial cells and therapy of human pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2926–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgos JS, Rosol M, Moats RA, Khankaldyyan V, Kohn DB, Nelson MD, Jr, et al. Time course of bioluminescent signal in orthotopic and heterotopic brain tumors in nude mice. Biotechniques. 2003;34:1184–1188. doi: 10.2144/03346st01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cerullo V, Seiler MP, Mane V, Brunetti-Pierri N, Clarke C, Bertin TK, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 triggers an innate immune response to helper-dependent adenoviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2007;15:378–385. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chartier C, Degryse E, Gantzer M, Dieterle A, Pavirani A, Mehtali M. Efficient generation of recombinant adenovirus vectors by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1996;70:4805–4810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4805-4810.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng SY, Huang HJ, Nagane M, Ji XD, Wang D, Shih CC, et al. Suppression of glioblastoma angiogenicity and tumorigenicity by inhibition of endogenous expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8502–8507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho HM, Rosenblatt JD, Kang YS, Iruela-Arispe ML, Morrison SL, Penichet ML, et al. Enhanced inhibition of murine tumor and human breast tumor xenografts using targeted delivery of an antibody-endostatin fusion protein. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:956–967. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damert A, Machein M, Breier G, Fujita MQ, Hanahan D, Risau W, et al. Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in a rat glioma is conferred by two distinct hypoxia-driven mechanisms. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3860–3864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Bouard S, Guillamo JS, Christov C, Lefevre N, Brugieres P, Gola E, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy against experimental glioblastoma using genetically engineered cells producing interferon-alpha, angiostatin, or endostatin. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:883–895. doi: 10.1089/104303403765701178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dvorak HF, Gresser I. Microvascular injury in pathogenesis of interferon-induced necrosis of subcutaneous tumors in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:497–502. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.7.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer I, Gagner JP, Law M, Newcomb EW, Zagzag D. Angiogenesis in gliomas: biology and molecular pathophysiology. Brain Pathol. 2005;15:297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman J. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Clinical applications of research on angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1757–1763. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M, Breitman ML. Role of the flt-1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating the assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature. 1995;376:66–70. doi: 10.1038/376066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldbrunner RH, Bendszus M, Wood J, Kiderlen M, Sasaki M, Tonn JC. PTK787/ZK222584, an inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, decreases glioma growth and vascularization. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:426–432. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000129551.64651.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graepler F, Verbeek B, Graeter T, Smirnow I, Kong HL, Schuppan D, et al. Combined endostatin/sFlt-1 antiangiogenic gene therapy is highly effective in a rat model of HCC. Hepatology. 2005;41:879–886. doi: 10.1002/hep.20613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerin C, Laterra J. Regulation of angiogenesis in malignant gliomas. EXS. 1997;79:47–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9006-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hlatky L, Hahnfeldt P, Folkman J. Clinical application of antiangiogenic therapy: microvessel density, what it does and doesn't tell us. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:883–893. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.12.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holland EC. Glioblastoma multiforme: the terminator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6242–6244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huszthy PC, Brekken C, Pedersen TB, Thorsen F, Sakariassen PO, Skaftnesmo KO, et al. Antitumor efficacy improved by local delivery of species-specific endostatin. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:118–128. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeda K, Ichikawa T, Wakimoto H, Silver JS, Deisboeck TS, Finkelstein D, et al. Oncolytic virus therapy of multiple tumors in the brain requires suppression of innate and elicited antiviral responses. Nat Med. 1999;5:881–887. doi: 10.1038/11320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imura S, Miyake H, Izumi K, Tashiro S, Uehara H. Correlation of vascular endothelial cell proliferation with microvessel density and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Invest. 2004;51:202–209. doi: 10.2152/jmi.51.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen RL, Ragel BT, Whang K, Gillespie D. Inhibition of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) decreases vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion and tumor growth in malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2006;78:233–247. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joki T, Machluf M, Atala A, Zhu J, Seyfried NT, Dunn IF, et al. Continuous release of endostatin from microencapsulated engineered cells for tumor therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:35–39. doi: 10.1038/83481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamiyama H, Takano S, Tsuboi K, Matsumura A. Anti-angiogenic effects of SN38 (active metabolite of irinotecan): inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1alpha)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression of glioma and growth of endothelial cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:205–213. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0642-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kargiotis O, Rao JS, Kyritsis AP. Mechanisms of angiogenesis in gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2006;78:281–293. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirsch M, Santarius T, Black PM, Schackert G. Therapeutic anti-angiogenesis for malignant brain tumors. Onkologie. 2001;24:423–430. doi: 10.1159/000055122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirsch M, Schackert G, Black PM. Angiogenesis, metastasis, and endogenous inhibition. J Neurooncol. 2000;50:173–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1006453428013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirsch M, Strasser J, Allende R, Bello L, Zhang J, Black PM. Angiostatin suppresses malignant glioma growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4654–4659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirsch M, Weigel P, Pinzer T, Carroll RS, Black PM, Schackert HK, et al. Therapy of hematogenous melanoma brain metastases with endostatin. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1259–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kisker O, Becker CM, Prox D, Fannon M, D'Amato R, Flynn E, et al. Continuous administration of endostatin by intraperitoneally implanted osmotic pump improves the efficacy and potency of therapy in a mouse xenograft tumor model. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7669–7674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuniyasu H, Ellis LM, Evans DB, Abbruzzese JL, Fenoglio CJ, Bucana CD, et al. Relative expression of E-cadherin and type IV collagenase genes predicts disease outcome in patients with resectable pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunkel P, Ulbricht U, Bohlen P, Brockmann MA, Fillbrandt R, Stavrou D, et al. Inhibition of glioma angiogenesis and growth in vivo by systemic treatment with a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6624–6628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuo CJ, Farnebo F, Yu EY, Christofferson R, Swearingen RA, Carter R, et al. Comparative evaluation of the antitumor activity of antiangiogenic proteins delivered by gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4605–4610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081615298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamfers ML, Fulci G, Gianni D, Tang Y, Kurozumi K, Kaur B, et al. Cyclophosphamide increases transgene expression mediated by an oncolytic adenovirus in glioma-bearing mice monitored by bioluminescence imaging. Mol Ther. 2006;14:779–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamszus K, Ulbricht U, Matschke J, Brockmann MA, Fillbrandt R, Westphal M. Levels of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 1 in astrocytic tumors and its relation to malignancy, vascularity, and VEGF-A. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1399–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Legler JM, Ries LA, Smith MA, Warren JL, Heineman EF, Kaplan RS, et al. Cancer surveillance series [corrected]: brain and other central nervous system cancers: recent trends in incidence and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1382–1390. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li XP, Li CY, Li X, Ding Y, Chan LL, Yang PH, et al. Inhibition of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma growth and metastasis in mice by adenovirus-associated virus-mediated expression of human endostatin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1290–1298. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu H, Peng CH, Liu YB, Wu YL, Zhao ZM, Wang Y, et al. Inhibitory effect of adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer of human endostatin on hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3331–3334. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maizel JV, Jr, White DO, Scharff MD. The polypeptides of adenovirus. I. Evidence for multiple protein components in the virion and a comparison of types 2, 7A, and 12. Virology. 1968;36:115–125. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(68)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maizel JV, Jr, White DO, Scharff MD. The polypeptides of adenovirus. II. Soluble proteins, cores, top components and the structure of the virion. Virology. 1968;36:126–136. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(68)90122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meneses PI, Abrey LE, Hajjar KA, Gultekin SH, Duvoisin RM, Berns KI, et al. Simplified production of a recombinant human angiostatin derivative that suppresses intracerebral glial tumor growth. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3689–3694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Millauer B, Shawver LK, Plate KH, Risau W, Ullrich A. Glioblastoma growth inhibited in vivo by a dominant-negative flk-1 mutant. Nature. 1994;367:576–579. doi: 10.1038/367576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morimoto T, Aoyagi M, Tamaki M, Yoshino Y, Hori H, Duan L, et al. Increased levels of tissue endostatin in human malignant gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2933–2938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nunes FA, Furth EE, Wilson JM, Raper SE. Gene transfer into the liver of nonhuman primates with E1-deleted recombinant adenoviral vectors: safety of readministration. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2515–2526. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oga M, Takenaga K, Sato Y, Nakajima H, Koshikawa N, Osato K, et al. Inhibition of metastatic brain tumor growth by intramuscular administration of the endostatin gene. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:73–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohlfest JR, Demorest ZL, Motooka Y, Vengco I, Oh S, Chen E, et al. Combinatorial antiangiogenic gene therapy by nonviral gene transfer using the sleeping beauty transposon causes tumor regression and improves survival in mice bearing intracranial human glioblastoma. Mol Ther. 2005;12:778–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peroulis I, Jonas N, Saleh M. Antiangiogenic activity of endostatin inhibits C6 glioma growth. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:839–845. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perri SR, Nalbantoglu J, Annabi B, Koty Z, Lejeune L, François M, et al. Plasminogen kringle 5-engineered glioma cells block migration of tumor-associated macrophages and suppress tumor vascularization and progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8359–8365. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plate KH, Breier G, Weich HA, Mennel HD, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor and glioma angiogenesis: coordinate induction of VEGF receptors, distribution of VEGF protein and possible in vivo regulatory mechanisms. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:520–529. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plate KH, Mennel HD. Vascular morphology and angiogenesis in glial tumors. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1995;47:89–94. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(11)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Plate KH, Risau W. Angiogenesis in malignant gliomas. Glia. 1995;15:339–347. doi: 10.1002/glia.440150313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Puduvalli VK, Sawaya R. Antiangiogenesis—therapeutic strategies and clinical implications for brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;50:189–200. doi: 10.1023/a:1006469830739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Radinsky R, Risin S, Fan D, Dong Z, Bielenberg D, Bucana CD, et al. Level and function of epidermal growth factor receptor predict the metastatic potential of human colon carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Read TA, Farhadi M, Bjerkvig R, Olsen BR, Rokstad AM, Huszthy PC, et al. Intravital microscopy reveals novel antivascular and antitumor effects of endostatin delivered locally by alginate-encapsulated cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6830–6837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Read TA, Sorensen DR, Mahesparan R, Enger PO, Timpl R, Olsen BR, et al. Local endostatin treatment of gliomas administered by microencapsulated producer cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:29–34. doi: 10.1038/83471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rege TA, Fears CY, Gladson CL. Endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis in malignant gliomas: nature's antiangiogenic therapy. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:106–121. doi: 10.1215/S115285170400119X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenstein JM, Mani N, Silverman WF, Krum JM. Patterns of brain angiogenesis after vascular endothelial growth factor administration in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7086–7091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubin JB, Kung AL, Klein RS, Chan JA, Sun Y, Schmidt K, et al. A small-molecule antagonist of CXCR4 inhibits intracranial growth of primary brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235846100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saleh M, Stacker SA, Wilks AF. Inhibition of growth of C6 glioma cells in vivo by expression of antisense vascular endothelial growth factor sequence. Cancer Res. 1996;56:393–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmidt NO, Ziu M, Carrabba G, Giussani C, Bello L, Sun Y, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy by local intracerebral microinfusion improves treatment efficiency and survival in an orthotopic human glioblastoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1255–1262. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shi SR, Key ME, Kalra KL. Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:741–748. doi: 10.1177/39.6.1709656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sipos EP, Brem H. Local anti-angiogenic brain tumor therapies. J Neurooncol. 2000;50:181–188. doi: 10.1023/a:1006482120049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Solorzano CC, Baker CH, Tsan R, Traxler P, Cohen P, Buchdunger E, et al. Optimization for the blockade of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling for therapy of human pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2563–2572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sonoda Y, Kanamori M, Deen DF, Cheng SY, Berger MS, Pieper RO. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms drives oxygenation and growth but not progression to glioblastoma multiforme in a human model of gliomagenesis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1962–1968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Steiner HH, Karcher S, Mueller MM, Nalbantis E, Kunze S, Herold-Mende C. Autocrine pathways of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in glioblastoma multiforme: clinical relevance of radiation-induced increase of VEGF levels. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:129–138. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000013495.08168.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Strik HM, Schluesener HJ, Seid K, Meyermann R, Deininger MH. Localization of endostatin in rat and human gliomas. Cancer. 2001;91:1013–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Song X, Zhang Y, Li K, et al. Results of phase III trial of EndostarTM (rh-endostatin, YH-16) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(16 Suppl):7138. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szentirmai O, Baker CH, Lin N, Szucs S, Takahashi M, Kiryu S, et al. Noninvasive bioluminescence imaging of luciferase expressing intracranial U87 xenografts: correlation with magnetic resonance imaging determined tumor volume and longitudinal use in assessing tumor growth and antiangiogenic treatment effect. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:365–372. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000195114.24819.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takano S, Kamiyama H, Tsuboi K, Matsumura A. Angiogenesis and antiangiogenic therapy for malignant gliomas. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2004;21:69–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02484513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takano S, Yoshii Y, Kondo S, Suzuki H, Maruno T, Shirai S, et al. Concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor in the serum and tumor tissue of brain tumor patients. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2185–2190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tanaka T, Cao Y, Folkman J, Fine HA. Viral vector-targeted antiangiogenic gene therapy utilizing an angiostatin complementary DNA. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3362–3369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tjin Tham Sjin RM, Naspinski J, Birsner AE, Li C, Chan R, Lo KM, et al. Endostatin therapy reveals a U-shaped curve for antitumor activity. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:619–627. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weidner N. Intratumor microvessel density as a prognostic factor in cancer. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis–correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Whitworth A. Endostatin: are we waiting for Godot? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:731–733. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamanaka R, Tanaka R. Gene therapy of brain tumor with endostatin. Drugs Today (Barc) 2004;40:931–934. doi: 10.1358/dot.2004.40.11.872581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoneda J, Kuniyasu H, Crispens MA, Price JE, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of angiogenesis-related genes and progression of human ovarian carcinomas in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:447–454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.6.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuan F, Chen Y, Dellian M, Safabakhsh N, Ferrara N, Jain RK. Time-dependent vascular regression and permeability changes in established human tumor xenografts induced by an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14765–14770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zagzag D, Amirnovin R, Greco MA, Yee H, Holash J, Wiegand SJ, et al. Vascular apoptosis and involution in gliomas precede neovascularization: a novel concept for glioma growth and angiogenesis. Lab Invest. 2000;80:837–849. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang X, Wu J, Fei Z, Gao D, Li X, Liu X, et al. Angiostatin K(1-3) gene for treatment of human gliomas: an experimental study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2000;113:996–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]