Abstract

We developed a subject-specific 3-D finite element model to understand the mechanics underlying formation of female pelvic organ prolapse, specifically a rectocele and its interaction with a cystocele. The model was created from MRI 3-D geometry of a healthy 45 year-old multiparous woman. It included anterior and posterior vaginal walls, levator ani muscle, cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, anterior and posterior arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, arcus tendineus levator ani, perineal body, perineal membrane and anal sphincter. Material properties were mostly from the literature. Tissue impairment was modeled as decreased tissue stiffness based on previous clinical studies. Model equations were solved using Abaqus v 6.11. The sensitivity of anterior and posterior vaginal wall geometry was calculated for different combinations tissue impairments under increasing intraabdominal pressure. Prolapse size was reported as POP-Q point at point Bp for rectocele and point Ba for cystocele. Results show that a rectocele resulted from impairments of the levator ani and posterior compartment support. For 20% levator and 85% posterior support impairments, simulated rectocele size (at POP-Q point: Bp) increased 0.29 mm/cm H2O without apical impairment and 0.36 mm/cm H2O with 60% apical impairment, as intraabdominal pressures increased from 0 to 150 cm H2O. Apical support impairment could result in the development of either a cystocele or rectocele. Simulated repair of posterior compartment support decreased rectocele but increased a preexisting cystocele. We conclude that development of rectocele and cystocele depend on the presence of anterior, posterior, levator and/or or apical support impairments, as well as the interaction of the prolapse with the opposing compartment.

Keywords: pelvic organ prolapse, rectocele, cystocele, finite element method, biomechanical model, pelvic floor

1. Introduction

Pelvic floor dysfunction, including pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence (SUI), leads one out of every ten women to undergo surgery in the U.S. (Olsen et al., 1997; Wu et al., 2014). Each year, over 200,000 operations are performed for prolapse (Boyles et al., 2003), with annual estimated cost for these operations exceeds US $1 billion (Subak et al., 2001).

A prolapse of the female pelvic organs can occur in one or both pelvic compartments. The anterior compartment contains the bladder and urethra while the posterior compartment contains the rectum and anus. The vagina separates these two compartments with its anterior and posterior vaginal walls. The upper portion of the vagina is suspended from the pelvic walls by cardinal ligament (CL) and uterosacral ligament (USL); these are actually mesenteric tissues that attach laterally to the pelvic sidewalls (DeLancey, 1992).

The underlying pathomechanics of cystocele, or anterior compartment prolapse, have begun to receive attention in terms of the associated geometric changes (Hsu et al., 2008a; Larson et al., 2010a; Larson et al., 2012a) as well as putative biomechanical changes (Chen et al., 2009). A knowledge gap remains, however, as to how and why a prolapse of the posterior compartment, a rectocele, forms. In addition, clinicians have recognized that there are important mechanical interactions between cystocele and rectocele. For example, surgical repair of one compartment is sometimes followed by development of new prolapse in the opposite compartment, despite its support appearing normal prior to the operation (Withagen et al., 2012). It is not clear why repairing one compartment unmasks weakness in the opposite compartment. Knowing how and why this occurs could lead to insights that could allow us to identify which women are risk for recurrence of prolapse following surgery so that the contralateral compartment could be reinforced at the time of the first operation.

The goal of this study, therefore, was to create a subject-specific 3-D anatomically-based finite element model which could develop either cystocele and/or rectocele depending on the particular impairments of the anterior and posterior pelvic compartment structural support systems. Of particular interest were the factors leading to the development of rectocele and comparing the results with observations in women with this condition. Furthermore, we sought to assess the model’s ability to simulate rectocele interactions with the anterior vaginal wall under increasing intraabdominal pressures. If corroborated by others, this 3D finite element model could help design better pelvic floor surgical repairs.

2. Methods

2.1 Subject-specific model anatomy and finite element mesh

The finite element model was based on geometric data from a 45 year-old multiparous healthy woman, who was selected from an ongoing University of Michigan Institutional Review Board-approved (IRB # 1999–0395) case-control study of pelvic organ prolapse. Her BMI was 28.5 kg/m2, vaginal parity was 2 and she had not undergone any pelvic floor surgery. Her height (163 cm) was at the 50th percentile for women in United States (Fryar et al., 2012). This subject’s vaginal dimensions (anterior vaginal wall: 59 mm; posterior vaginal wall: 98 mm; cervix: 38 mm) were also near the 50th percentile of healthy women (Luo et al., 2012a).

As described in our previous work (Luo et al., 2012b), the subject underwent supine multi-planar, two-dimensional, fast spin, proton density MR imaging both at rest and during maximal Valsalva using a 3T superconducting magnet (Philips Medical Systems Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) with version 2.5.1.0 software. At rest, 30 images were serially obtained in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes using a 20×20 cm field of view, 4 mm slice thickness, and a 1 mm gap between slices. Similarly, at maximal Valsalva, which a patient can only hold for a short time, 14 images were serially obtained in the same three planes using 6 mm slice thickness and 1 mm gap, and with larger fields of view (36×36 cm) in order to image the entire prolapse. In order for the images to be considered adequate, visualization of vaginal margins was required.

A detailed 3-D pelvic floor model which included 23 structures was created, as previously described (Luo et al., 2011), using 3D Slicer software (version 3.4.1; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA). Each structure was traced using the most clearly visible axial and/or coronal plane images and lofted into a 3D virtual model based on our previous anatomic work (Brandon et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2005; Hsu et al., 2008b; Larson et al., 2010b; Margulies et al., 2006). The volumetric 3D model was imported into Imageware (version 13.0; Siemens Product Lifecycle Management Software Inc., 2008). Vaginal walls, levator ani (consisting of pubococcygeal muscle, iliococcygeal muscle, and puborectal muscle), and other pelvic floor structures were lofted to form smooth surfaces. The simplified models were then imported into Abaqus (version 6.11, Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp., Providence, RI, USA), to generate the structural mesh used to simulate the prolapse. The model development process is shown schematically in Figure 1. Detailed pelvic floor structures’ origin, insertion and connections are tabulated in the Supplemental Materials (SM Table).

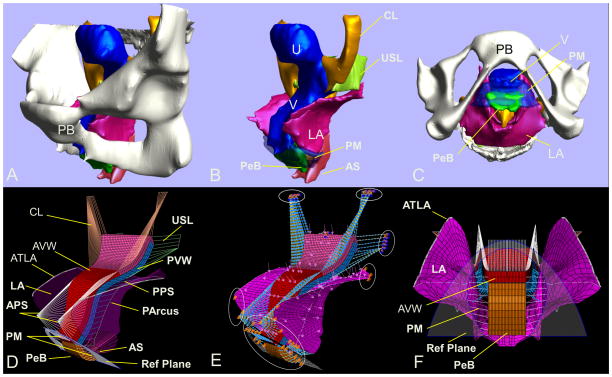

Figure 1.

Model development: (A) and (B) MR based 3D pelvic floor reconstruction model with and without bone in a left three quarter view in the standing posture, and (C) in a bottom view with bone; (D) and (E) 3-D finite element model in left three quarter view and (F) in a bottom view. LA is shown as semi-transparent to reveal the structures behind in (D). Load and boundary conditions (BCs) are shown in (E). Reference plane, shown as semi-transparent in (F), displays the approximate position of the hymen at rest, and is used for visualizing the development of prolapse. PB denotes pubic bone; U, uterus; V, vagina; CL, cardinal ligament; USL, uterosacral ligament; PeB, perineal body; PM, perineal membrane; LA, levator ani; AVW, anterior vaginal wall; PVW, posterior vaginal wall; APS, anterior paravaginal support; PArcus, posterior arcus tendineus fascia pelvis; PPS, posterior paravaginal support; AS, anal sphincter; ATLA, arcus tendineus levator ani.

The 3D finite element model mesh was generated by Abaqus CAE mesh module and the simulation was solved using Abaqus Explicit Solver.

The finite element model consisted of a total of 7,182 elements and 10,151 nodes (Figure 1). The anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, and perineal body were modeled using 3D deformable elements consisting of 5 mm-thick, 8-node, linear, hexagonal elements using reduced integration. The levator ani muscle was modeled as a deformable shell element using 4 mm-thick 4-node quadrilateral elements using reduced integration. The hymenal reference plane was simulated as a display body so that differences of the pelvic organs could be more easily appreciated. The cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, anterior vaginal support, and posterior vaginal support were simulated using nonlinear elastic connector elements. The arcus tendineus levator ani (ATLA) and posterior arcus were simulated using 2-node linear 3D truss elements. Each single simulation took about 4 hours to solve on a Linux-based (Red Hat Enterprise Linux version 5.8) High Performance Computing (HPC) cluster. The cluster, based on the Intel platform, consisted of four parallel 2.67 GHz cores (Intel Xeon X5650 processors) with 4 GB RAM per core interconnected with 40 Gbps InfiniBand networking.

2.2 Model contact and boundary conditions

The boundary conditions were determined based on the pelvic floor structures’ anatomical origin, insertion and supporting structures (SM Table). Contact between anterior and posterior vaginal wall, and between posterior vaginal wall – levator ani, were modeled using a frictionless, finite sliding, penalty contact algorithm. The origins of the perineal membrane from the pubic bone were fixed for translation but permitted rotation. The edges of the perineal body were connected with the levator ani using connector elements. The top edges of levator ani, the iliococcygeal portion (ICM) were tied to the ATLA. The origin and insertion of ATLA were both located on the pelvis and therefore set to be fixed for translation but allow rotation. The front edges of the levator ani and posterior edges of the levator ani were fixed for translation but also allowed rotation. The posterior arcus was tied to the levator ani, and the origin and insertion of posterior arcus were fixed for translation but allowed rotation. The origins of anterior vaginal support lay on the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP) in 3-D space. All the origins for the anterior vaginal support and apical vaginal supports were fixed for translation but allowed rotation.

2.3 Model material properties

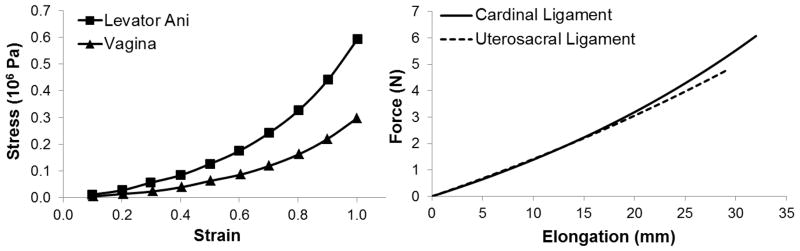

In this study all the deformable structures, including the connector elements, were assumed to be hyperelastic. For simplicity, the hyperelastic deformed structures was assumed to be isotropic and quasi-incompressible while using Abaqus Explicit Solver. The material properties values of the vagina and levator ani muscle were taken from the published literature (Yamada, 1970) as used in our previous study (Chen et al., 2009) (Figure 2). For the constitutive model of vagina and levator ani muscle, we assumed the strain energy density is a function of the first invariant of the strain tensor and so used the Marlow model (Marlow 2003), a general first invariant constitutive model:

| (1) |

where W is the strain energy density function and I1 is the first invariant of the green deformation sensor. The Marlow model does not contain any explicit relation between strain energy density and/or invariants and/or stretch ratios. The constitutive model was evaluated in Abaqus and the evaluation result showed that it was stable. The material properties values for the apical supports and uterine support tissues, which include a cardinal ligament (CL) and uterosacral ligament (USL) on each side of the vagina, were taken from our recent in vivo tissue tests (Luo et al., 2014b; Smith et al., 2013) on healthy women. In those studies we used a computer-controlled linear servo actuator to apply a continuous force and simultaneously recorded cervical displacement. A simplified four-cable model was then used to analyze the material behavior of each ligament. The model calculated force-elongation curves of CL and USL are shown in Figure 2, and the nonlinear force-displacement mechanical functions of CL and USL are:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where d is the elongation (mm), FCL and FUSL are the corresponding tensile forces (N) on the ligaments. The behavior of the levator muscle was only considered under passive stretch, since during the Valsalva maneuver patients were specifically coached to “relax their pelvic floor muscles as much as possible”. Because there are no data for the material properties of anterior and posterior paravaginal supports, their material properties for this subject-based model was first estimated based on our experience, then were derived via an iterative calibration process, whereby the final value was considered as 0% impairment baseline. The objective of the calibration was to make sure the subject-based model simulation had the same behavior as the subject exhibited under intrabdominal pressure in the absence of any impairment.

Figure 2.

The mechanical material properties of vagina, levator ani muscle, cardinal ligament, and uterosacral ligament used in this model simulation.

2.4 Simulation process

The purpose of the simulation was to predict how the anterior and posterior compartment structures and supports would deform under increasing intraabdominal pressure such as when straining or doing a Valsalva. Sensitivity analyses were performed using different combinations of muscular and connective tissue impairments under different maximum intraabdominal pressure values. The impairment was simulated as decreased tensile stiffness, given the linear relationship between striated muscle contractile force and its tensile stiffness (Blanpied and Smidt, 1993). As there is an average 40% decrease in maximum contraction force seen in women with prolapse, compared to women without prolapse with levator ani condition identified by MR images (DeLancey et al., 2007), the simulated impairment of levator ani muscle we used was from 20% to 60%. We used a 90% impairment value as the maximum impairment value to simulate the condition when the connective tissue was totally detached from its original place for prolapse women, as can be seen on MR images (Larson et al., 2012b). The maximum simulated pressure value was 150 cm H2O, which is in the physiologic range given that patients in our previous studies exhibited intraabdominal pressures of 142 ± 38 (32 ~ 331) cm H2O under maximum Valsalva (DeLancey et al., 2007), and 126 ± 34 cm H2O (continent), 143 ± 43 cm H2O (incontinent) under maximum cough (DeLancey et al., 2008). The prolapse size was quantified by POP-Q parameters Ba and Bp (Bump et al., 1996). These points are defined as the location on the anterior (Ba) and posterior (Bp) vaginal walls that lie 3 cm above the hymenal ring. The intraabdominal pressure was applied perpendicular to nodes on the surface of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, perineal body, and levator ani. To reduce computation time, and to simulate the Valsalva process, the simulation time was scaled to 1 second.

2.5 Model validation

Photographic images of a prolapse under maximal Valsalva pressure were used to qualitatively validate a developing prolapse in the simulations. The model was further qualitatively validated by comparing the deformations of the model anterior and posterior vaginal walls against published 3-D measurements of cystocele and rectocele deformation in 3-D Stress MR studies of women with these conditions (Larson et al., 2010a; Luo et al., 2012b) to check whether predicted prolapse deformation characteristics were reasonable.

3. Results

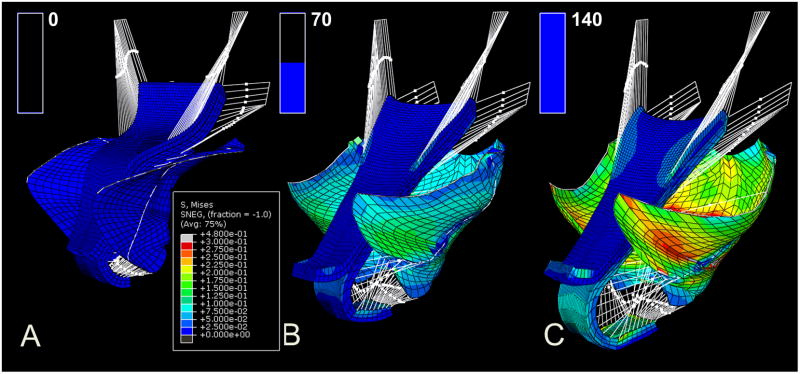

To visualize the development of a typical rectocele, Figure 3 shows the model simulation under systematically increasing values of intraabdominal pressure given 50% levator impairment, 70% apical impairment and 85% posterior support impairment, and with no anterior support impairment.

Figure 3.

The sequential development of a typical rectocele in a three-quarter, left and anterior view of the pelvic cavity. The load condition from (A), to (B) and (C) is under 0, 70, and 140 cm H2O. The color map shows the stress distribution in different regions, with blue indicating a low stress, green indicating a medium stress, and red indicating high stress. The bar graph in the upper left corner of each panel shows the intraabdominal pressure (0 to 140 cm H2O) applied to the pelvic floor sequentially in time from (A) to (C).

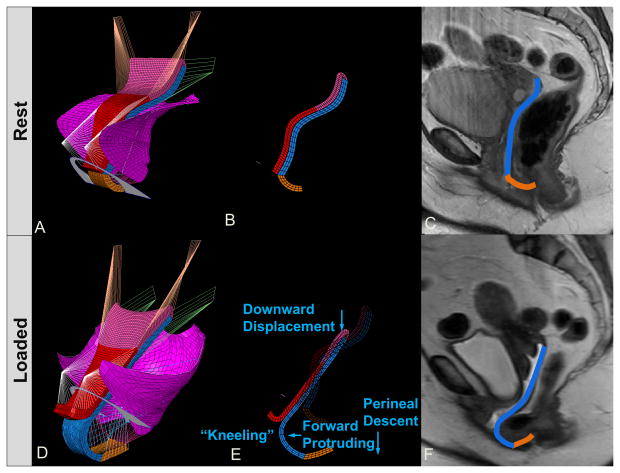

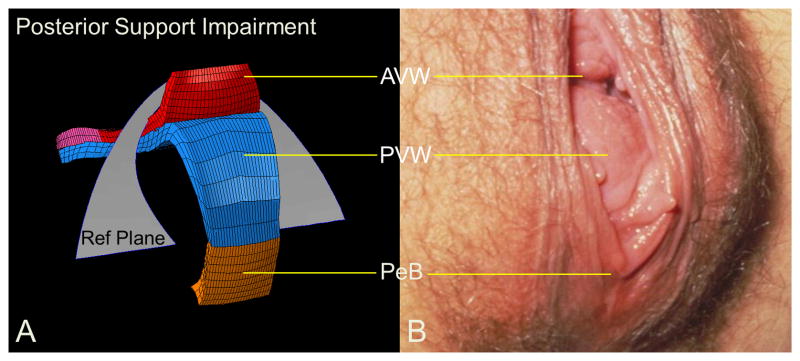

The model-generated simulation results for a rectocele are similar to those seen during the clinical examination of a patient with rectocele who is performing a Valsalva (Figure 4B). The characteristic downward displacement, forward protrusion, and perineal descent as well as the “kneeling” profile of the rectocele matching those seen in 3-D stress MRI (Luo et al., 2012b) can also be seen in the model results (Figure 5D, E and F). One can also see that the CL and USL lengthen under the application of pressure. In addition, the angle subtended by those two ligaments with the body axis changes from rest to max Valsalva, with the change in inclination for the USL being larger than that for the CL (Figure 5D), as seen in living women (Luo et al., 2014a).

Figure 4.

Rectocele. (A) shows a model generated simulation result of rectocele formed in the manner of one seen clinically in a picture from one patient performing a Valsalva in (B).

Figure 5.

Rectocele characteristics shown in left three quarter view for the model at rest (A) and under load (D). Panel (B) shows mid-sagittal plane section of model at rest. In (E), “kneeling”, downward displacement, forward protruding, and perineal descent behaviors are seen for the rectocele. Static MR (C) and “Stress MR” (F) have posterior vaginal wall outlined in blue and perineal body in brown.

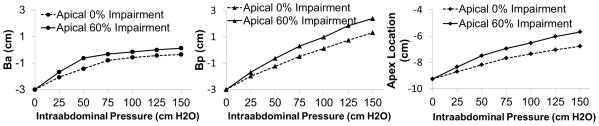

The biomechanical effects of changes in intraabdominal pressure and apical support on rectocele size are shown in Figure 6. These simulations were run with 20% levator impairment, 85% posterior support impairment and no anterior support impairment. The results show both Ba and Bp dimensions increasing as increasing intraabdominal pressure was applied. We found that the greater the impairment in the cardinal and uterosacral ligament, the larger the rectocele size. Note, however, that the Bp dimension changed more quickly than Ba did when only posterior support impairment was present. The apical location moved caudally with both larger intraabdominal pressure and greater apical impairment. Without apical impairment, the compliance was 0.17 mm/cm H2O for anterior compartment, 0.29 mm/cm H2O for posterior compartment and 0.18 mm/cm H2O for the apex. But with 60% apical impairment, the compliance increased to 0.21 mm/cm H2O for anterior compartment, 0.36 mm/cm H2O for posterior compartment and 0.25 mm/cm H2O for the apex.

Figure 6.

Prolapse size with effect of intraabdominal pressure and apical impairment with levator ani 20% impairment, posterior 85% impairment, and no anterior impairment.

We next examined the effect of levator support. A 140 cm H2O load was first applied in the presence of a 30% apical impairment, 85% posterior support impairment and normal anterior support. In this situation all the Ba parameter values were less than zero (i.e., above the hymen) and the Bp values were greater than zero (i.e., below the hymen). When the levator impairment was changed from 40% to 60%, the Bp parameter values were nearly twice as large as those when levator impairment was changed from 20% to 40% but with absolute value change was less than 0.2 cm. When levator and apical support impairment were combined, the Bp values change from 0.4 cm to 0.9 cm when levator and apical impairments were increased from 20% and 30% to 60% and 60%, respectively.

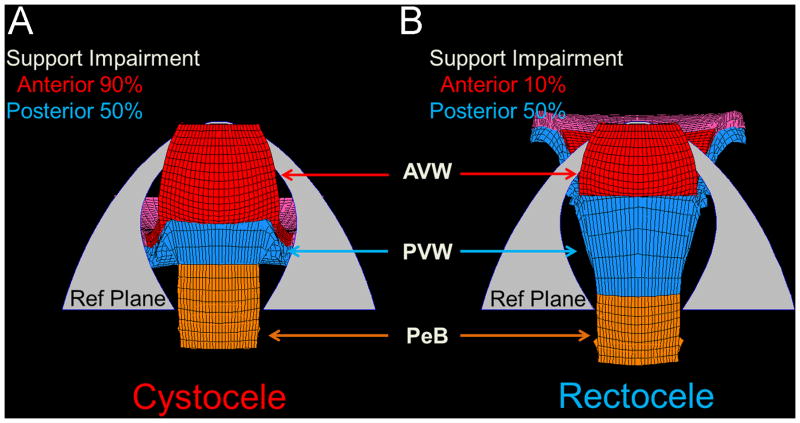

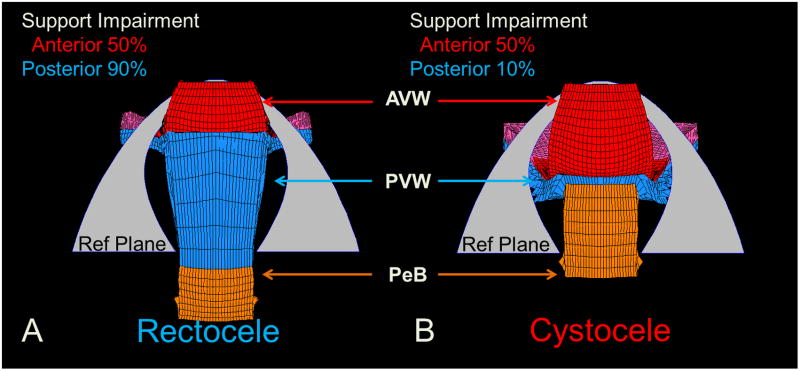

The finite element model also shows the mechanical interactions between cystocele and rectocele that represents the clinical phenomenon of ‘organ competition’ whereby the two vaginal walls compete for the limited opening, or genital hiatus, in the pelvic floor through which prolapse occurs (Figures 7 & 8). Under the same simulation conditions (140 cm H2O, levator 50% impairment and apical 80% impairment) variation in prolapse sizes were found for different anterior or posterior support impairments. For example, as shown in Figure 7, reducing posterior compartment support impairment from 90% to 10% reduces the rectocele size by 3 cm, but increased cystocele by 1 cm. Thus, in this situation, repair of posterior compartment support in (B) reduces the rectocele size, but increased cystocele.

Figure 7.

Inferior view of simulation results demonstrating what happens to the anterior compartment when impairments to the posterior compartment are decreased, as they would be after surgical repair under conditions with 140 cm H2O and impairments of 50% for the levator ani, 80% for apical supports and 50% for anterior supports. (A) shows a model-generated rectocele (Ba=−1, Bp=1 cm) with posterior support impairment of 90% impairment. (B) with reduction of the posterior support impairment to 10% a cystocele develops (points Ba=0, Bp=−2 cm) despite no change in anterior support stiffness.

Figure 8.

Inferior view of the simulation demonstrating what happens to the posterior compartment when impairments to the anterior compartment are decreased, as they would be after surgical repair under conditions with 140 cm H2O and impairments of 50% for the levator ani and 50% for posterior supports. Panel (A) shows a model-generated cystocele (Ba=1, Bp=−1 cm) with anterior support 90%. Panel (B) shows that with reduction of anterior support impairments to 10% a rectocele develops (Ba=0, Bp=1 cm) despite no change in posterior support stiffness.

Similarly, Figure 8 shows that when anterior impairment is reduced from 90% to 10% this reduces cystocele size by 1 cm, but increased rectocele by 2 cm.

4. Discussion

This subject-specific finite element model is based on the anatomy of a healthy woman who had no prolapse upon clinical examination, and includes the muscular and connective tissue structures that determine anterior and posterior compartment support. Hence it includes not just the organs but the important connecting structures such as the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, both anterior and posterior tendineus arches, as well as the perineal body, perineal membrane that determine structural support of the two compartments so that changes in individual elements can be implemented and the consequences seen. When this model was subjected to physiologically relevant pressures, specific changes having been made to reflect impairments in the stiffness of the support structures, it suggested that the model simulated deformations were morphologically similar to both posterior and anterior compartment prolapses which were observed clinically. In addition it demonstrates that changes in one compartment can affect support in the other compartment, displaying the ability to interrogate interactions between anterior and posterior compartment support. The biomechanics of this clinically important issue, known as organ competition, have not previously been simulated. By allowing the consequences of specific alterations in individual components of the support system to be studied the model facilitates analyses that can never ethically be conducted in human subjects. The simulation results are similar to cystocele and rectocele seen during clinical exams and they also exhibit similarities to the geometry of 3D models based on sequential images taken during “Stress” MR examinations of women with anterior and posterior compartment prolapse made during a Valsalva maneuver (Larson et al., 2010a; Luo et al., 2012b). The model should prove useful for planning surgeries for different types of impairment.

Several computer models have been used to evaluate structural mechanics of individual portions of pelvic floor. For example, finite element models have studied the cystocele (Chen et al., 2009; Mayeur et al., 2014). A series of finite element models studied the levator ani muscle (d’Aulignac et al., 2005; Noakes et al., 2008), vaginal birth (Hoyte et al., 2008; Jing et al., 2012; Li et al., 2010; Parente et al., 2009), and female incontinence (Zhang et al., 2009). Our FE model, that contains the structurally complex posterior compartment extends these models and allows posterior compartment prolapse or rectocele to be simulated. In addition, having this compartment now allows its interaction with cystocele to be quantified so that organ competition can be evaluated, thereby extending published pelvic floor computer models.

Clinically, one of the important causes of recurrent prolapse after surgical repair occurs when prolapse occurs in, for example, the seemingly normal posterior compartment after anterior compartment repair (Withagen et al., 2012). Having a tool to help understand how and why this occurs can help provide insights that might lead to better detection preoperatively. Based on the simulation results shown in Figures 7 & 8, where the size of the rectocele or cystocele was altered by changing the supports of the opposite compartment, our findings show that the size of rectocele and cystocele are not only dependent on the impairments of anterior and posterior support, but also on impairments of the levator muscle and apical support system. It may seem, at first, that the changes in anterior and posterior support are relatively modest for the degree of impairment we prescribed. In addition, the model clearly demonstrates that there is a mechanical interaction between the development of anterior and posterior prolapse via organ competition as has been observed clinically (Kelvin and Maglinte, 1997): when one vaginal wall prolapses first, it can fill the genital hiatus thereby blocking prolapse of the other wall, and vice versa. When levator muscle and apical impairment are combined with anterior and posterior wall support impairment, prolapse results. A novel finding from the present model is consistent with the hypothesis that development of a cystocele tends to protect the posterior compartment from prolapsing under increasing intraabdominal pressure, and a rectocele tends to likewise protect the anterior compartment from prolapsing. The model’s ability to examine the interaction will allow sensitivity analyses for the many different combinations of impairments that are possible.

Earlier clinical work has demonstrated that levator and apical impairments result in anterior compartment failure resulting in cystocele (DeLancey et al., 2007; Dietz and Simpson, 2008; Summers et al., 2006); this has also been confirmed by computer model simulation (Chen et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2006). The present modeling study corroborates these results, but goes on to demonstrate that levator and apical impairments can also contribute to rectocele; a topic not previously clarified. We noticed that rectocele size increased with greater levator impairment. So, a larger levator impairment will decrease the vaginal closure force and allow a greater length of the vaginal wall to be exposed to the pressure differential (the difference between intraabdominal pressure and atmospheric pressure) acting across the exposed vaginal wall, thus fostering the development of cystocele or rectocele. We also found that anterior support impairment often gave rise to cystocele, while posterior support impairment more often gave rise to rectocele in that Bp changes more than Ba for isolated posterior impairment. This can easily be explained by the driving force emanating from the pressure difference between the large intraabdominal pressure and small atmospheric pressure applied on each compartment and with the supporting force provided by the support system structures. With less anterior or posterior support, the support system will reduce the anterior or posterior support force, then the less-supported compartment will deform more. This model also shows the importance of the apical supports. We saw that a 60% impairment of the apical supports led to a larger prolapse (1 cm bigger) and more apical descent than those with normal apical supports under the simulated conditions (c.f., Figure 6).

The finding that the degree of intraabdominal pressure rise is correlated with increasing prolapse shows that the model reproduces pelvic floor behavior in the clinic. It is consistent with the widely held concept that prolapse and increased abdominal pressure are related (Chen et al., 2009;). We can infer that with more levator and apical impairment, the compliance of the posterior compartment will increase. While the anterior and posterior compartments are not equilibrated, a larger intraabdominal pressure will definitely lead to a larger prolapse. Chronic coughing (Rinne and Kirkinen, 1999), heavy physical activity (Woodman et al., 2006), and obesity (Hendrix et al., 2002; Moalli et al., 2003), etc. are all associated with chronically increased intraabdominal pressure, so women with a small prolapse are advised to reduce chronic increases in intraabdominal pressure by reducing the above symptoms or activities.

Our approach has several methodological limitations that should be kept in mind in interpreting our results. Firstly, we had to simplify the geometry of the vaginal wall and levator muscle in order to keep the computational time tractable. Secondly, we did not consider the effect of actively contracting levator ani muscle. Increasing muscle contraction intensity is known to increase the tensile stiffness of muscle (Blanpied and Smidt, 1993), so increases in muscle tone or muscle volume would increase levator resistance to stretch. Thirdly, we only considered isotropic hyperelastic material properties in this study. Effects of fiber direction on pelvic floor soft tissue behavior would be valuable to consider. Some simulations only showed small change of prolapse size at a single point in time, but this could be amplified over many years by hysteresis and repeated loading. Further work will be needed to include the time-dependent material properties of the levator ani muscle and passive connective tissues. Our simulation results are therefore conservative estimates of the deformation, which would be expected to increase with time under sustained loading due to viscous effects. Fourth, in order to evaluate the two support systems separately we have not yet evaluated the effect of connecting the anterior and posterior vaginal walls at their lateral margins. The deformations present in this model might be smaller if those connections provide resistance to deformation. Fifth, our understanding of the mechanics of the apical supports is evolving; they are likely more complex than the current clinical paradigms suggest. In this present work, we simulated apical defects by decreasing its stiffness. Although functionally this led to prolapse, we also need to include other types of tissue behavior such as hysteresis and tissue remodeling in future models. Sixth, the purpose of this simulation was to investigate the mechanisms of rectocele. Enterocele, which also involves the posterior vaginal wall, was not addressed. Finally, the present model only considered average size pelvic floor geometry and normal initial geometry; further work will be needed to evaluate how variations in initial geometry affect prolapse behavior.

This anatomically based multi-compartment model permits interactions between the anterior and posterior compartment and produces results similar to those seen clinically. It may prove to be a useful tool in understanding the cause and consequences of structural problems found in the 200,000 women who require surgery each year for prolapse and should assist in a long-term goal of reducing operative recurrence; especially as it relates to the issue of organ competition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants R01 HD 038665, the Office for Research on Women’s Health SCOR on Sex and Gender Factors Affecting Women’s Health P50 HD 044406, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences 2UL1TR000433 and BIRCWH K12 HD004438.

Footnotes

5. Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. John O. DeLancey and Dr. James A. Ashton-Miller do not have any conflicts of interest directly related to this study. The University of Michigan received funding from Johnson & Johnson, American Medical Systems, Kimberly-Clark Corporation, Proctor & Gamble, and Boston Scientific Corporation as partial salary support for research unrelated to the topic of this paper. They also received an honorarium and travel reimbursement for giving an invited research seminar at Johnson & Johnson.

Drs. Dee Fenner and Luyun Chen receive research support from American Medical System unrelated to the topic of this paper.

Dr. Jiajia Luo does not have any directly related conflicts of interest for this study, but his doctoral studies were partially funded by American Medical Systems and Kimberly Clark Corporation unrelated to the topic of this paper, and he also received research support from Boston Scientific Corporation unrelated to the topic of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Blanpied P, Smidt GL. The difference in stiffness of the active plantarflexors between young and elderly human females. Journal of gerontology. 1993;48:M58–M63. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.2.m58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States, 1979–1997. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;188:108–115. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon CJ, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Larson KA, Delancey JO. Anatomy of the perineal membrane as seen in magnetic resonance images of nulliparous women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2009;200:583 e581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, Shull BL, Smith AR. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1996;175:10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. A 3D finite element model of anterior vaginal wall support to evaluate mechanisms underlying cystocele formation. Journal of biomechanics. 2009;42:1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, Hsu Y, DeLancey JO. Interaction among apical support, levator ani impairment, and anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;108:324–332. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000227786.69257.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Aulignac D, Martins JA, Pires EB, Mascarenhas T, Jorge RM. A shell finite element model of the pelvic floor muscles. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering. 2005;8:339–347. doi: 10.1080/10255840500405378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1992;166:1717–1724. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o. discussion 1724–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLancey JOL, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, Kearney R, Guire K, Miller JM, Hussain H, Umek W, Hsu Y, Ashton-Miller JA. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;109:295–302. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250901.57095.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLancey JOL, Trowbridge ER, Miller JM, Morgan DM, Guire K, Fenner DE, Weadock WJ, Ashton-Miller JA. Stress urinary incontinence: Relative importance of urethral support and urethral closure pressure. Journal of Urology. 2008;179:2286–2290. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz H, Simpson J. Levator trauma is associated with pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008;115:979–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryar CD, Gu Q, Ogden CL. Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2007–2010. National Center for Health Statistics Vital and Health Statistics. 2012;11:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;186:1160–1166. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyte L, Damaser MS, Warfield SK, Chukkapalli G, Majumdar A, Choi DJ, Trivedi A, Krysl P. Quantity and distribution of levator ani stretch during simulated vaginal childbirth. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;199:198 e191–198 e195. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y, Chen LY, Summers A, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. Anterior vaginal wall length and degree of anterior compartment prolapse seen on dynamic MRI. International Urogynecology Journal. 2008a;19:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0405-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y, Fenner DE, Weadock WJ, DeLancey JO. Magnetic resonance imaging and 3-dimensional analysis of external anal sphincter anatomy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;106:1259–1265. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000189084.82449.fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y, Lewicky-Gaupp C, DeLancey JO. Posterior compartment anatomy as seen in magnetic resonance imaging and 3-dimensional reconstruction from asymptomatic nulliparas. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008b;198:651 e651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing D, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. A subject-specific anisotropic visco-hyperelastic finite element model of female pelvic floor stress and strain during the second stage of labor. Journal of biomechanics. 2012;45:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelvin FM, Maglinte DDT. Dynamic cystoproctography of female pelvic floor defects and their interrelationships. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1997;169:769–774. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.3.9275894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson KA, Hsu Y, Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Magnetic resonance imaging-based three-dimensional model of anterior vaginal wall position at rest and maximal strain in women with and without prolapse. International urogynecology journal. 2010a;21:1103–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson KA, Luo J, Guire KE, Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. 3D analysis of cystoceles using magnetic resonance imaging assessing midline, paravaginal, and apical defects. International urogynecology journal. 2012a;23:285–293. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1586-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson KA, Luo J, Yousuf A, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. Measurement of the 3D geometry of the fascial arches in women with a unilateral levator defect and “architectural distortion”. Int Urogynecol J. 2012b;23:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1528-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson KA, Yousuf A, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Fenner DE, DeLancey JO. Perineal body anatomy in living women: 3-dimensional analysis using thin-slice magnetic resonance imaging. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010b;203:494 e415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Kruger JA, Nash MP, Nielsen PM. Effects of nonlinear muscle elasticity on pelvic floor mechanics during vaginal childbirth. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 2010;132:111010. doi: 10.1115/1.4002558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. A model patient: Female pelvic anatomy can be viewed in diverse 3-dimensional images with a new interactive tool. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;205:391 e391–391.e392. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Betschart C, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. MR-Based Analysis of Variation in Vaginal Dimensions and Symmetry. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery. 2012a;18:S99. [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Betschart C, Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. Using stress MRI to analyze the 3D changes in apical ligament geometry from rest to maximal Valsalva: a pilot study. International urogynecology journal. 2014a;25:197–203. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2211-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Larson KA, Fenner DE, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. Posterior vaginal prolapse shape and position changes at maximal Valsalva seen in 3-D MRI-based models. International urogynecology journal. 2012b;23:1301–1306. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1760-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Smith TM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. In vivo properties of uterine suspensory tissue in pelvic organ prolapse. J Biomech Eng. 2014b;136:021016. doi: 10.1115/1.4026159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies RU, Hsu Y, Kearney R, Stein T, Umek WH, DeLancey JO. Appearance of the levator ani muscle subdivisions in magnetic resonance images. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;107:1064–1069. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000214952.28605.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeur O, Lamblin G, Lecomte-Grosbras P, Brieu M, Rubod C, Cosson M. Biomedical Simulation. Springer; 2014. FE Simulation for the Understanding of the Median Cystocele Prolapse Occurrence; pp. 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Moalli PA, Ivy SJ, Meyn LA, Zyczynski HM. Risk factors associated with pelvic floor disorders in women undergoing surgical repair. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;101:869. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes KF, Pullan AJ, Bissett IP, Cheng LK. Subject specific finite elasticity simulations of the pelvic floor. Journal of biomechanics. 2008;41:3060–3065. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell KK, Morse AN, Crawford SL, Howard A. Vaginal pressure during lifting, floor exercises, jogging, and use of hydraulic exercise machines. International Urogynecology Journal. 2007;18:1481–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1997;89:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente MPL, Natal Jorge RM, Mascarenhas T, Fernandes AA, Martins JAC. The influence of the material properties on the biomechanical behavior of the pelvic floor muscles during vaginal delivery. Journal of biomechanics. 2009;42:1301–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne KM, Kirkinen PP. What predisposes young women to genital prolapse? European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1999;84:23–25. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TM, Luo J, Hsu Y, Ashton-Miller J, Delancey JO. A novel technique to measure in vivo uterine suspensory ligament stiffness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:484 e481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subak LL, Waetjen LE, van den Eeden S, Thom DH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;98:646–651. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers A, Winkel LA, Hussain HK, DeLancey JO. The relationship between anterior and apical compartment support. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;194:1438–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withagen MI, Milani AL, De Leeuw JW, Vierhout ME. Development of de novo prolapse in untreated vaginal compartments after prolapse repair with and without mesh: A secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012;119:354–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman PJ, Swift SE, O’Boyle AL, Valley MT, Bland DR, Kahn MA, Schaffer JI. Prevalence of severe pelvic organ prolapse in relation to job description and socioeconomic status: a multicenter cross-sectional study. International Urogynecology Journal. 2006;17:340–345. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;123:1201–1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H. Strength of biological materials. Strength of Biological Materials 1970 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Kim S, Erdman AG, Roberts KP, Timm GW. Feasibility of using a computer modeling approach to study SUI Induced by landing a jump. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2009;37:1425–1433. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.