Abstract

Hindlimb unloading (HU) is a well-established animal model of cardiovascular deconditioning. Previous data indicate that HU results in cardiac sympathovagal imbalance. It is well established that cardiac sympathovagal imbalance increases the risk for developing cardiac arrhythmias. The cardiac gap junction protein connexin 43 (Cx43) is predominately expressed in the left ventricle (LV) and ensures efficient cell-to-cell electrical coupling. In the current study we wanted to test the hypothesis that HU would result in increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias and alter the expression and/or phosphorylation of LV-Cx43. Electrocardiographic data using implantable telemetry were obtained over a 10- to 14-day HU or casted control (CC) condition and in response to a sympathetic stressor using isoproterenol administration and brief restraint. The arrhythmic burden was calculated using a modified scoring system to quantify spontaneous and provoked arrhythmias. In addition, Western blot analysis was used to measure LV-Cx43 expression in lysates probed with antibodies directed against the total and an unphosphorylated form of Cx43 in CC and HU rats. HU resulted in a significantly greater total arrhythmic burden during the sympathetic stressor with significantly more ventricular arrhythmias occurring. In addition, there was increased expression of total LV-Cx43 observed with no difference in the expression of unphosphorylated LV-Cx43. Specifically, the increased expression of LV-Cx43 was consistent with the phosphorylated form. These data taken together indicate that cardiovascular deconditioning produced through HU results in increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias and increased expression of phosphorylated LV-Cx43.

Keywords: hindlimb suspension, microgravity, deconditioning, depression, sympathetic, parasympathetic

hindlimb unloading (HU) in rats is a well-established model used to simulate the effects of microgravity and results in deconditioning of the cardiovascular system (34). Elevation of the rat's hindlimbs through tail suspension results in activation of cardiopulmonary receptors in response to immediate fluid shifts followed by reflex reductions in blood and plasma volume (12, 30, 37). After 14 days of HU, these animals experience resting tachycardia, baroreflex dysfunction, and decreased exercise capacity in the normal posture (31, 32, 35, 58). These effects are similar to those observed in humans following exposure to prolonged bedrest or a microgravity environment (9, 11, 15, 21, 43).

Previous data indicate that HU results in cardiac sympathovagal imbalance (33, 35). We found that selective autonomic blockade in male, Sprague-Dawley rats confined to 14 days of HU revealed an augmented reduction in heart rate (HR) to intravenous administration of the β-blocker propranolol and were lacking cardiac parasympathetic (vagal) tone to the heart as intravenous administration of atropine produced little increase in HR. Heart rate variability (HRV) was also significantly reduced in these animals as evidenced by the reduction in the standard deviation of the normal-to-normal pulse interval variability (SDNN) (33).

Cardiac sympathovagal imbalance increases the risk for developing fatal arrhythmias (48, 56, 61) and indicates poor prognosis following cardiovascular insult or injury (26, 53). Both increases in cardiac sympathetic nervous system activity (20, 46, 52, 61), as well as reductions in cardiac parasympathetic tone in both humans and animals, have been implicated in increased arrhythmogenic risk (18, 19, 55) presumably through loss of accentuated antagonism. Our previous data indicate a dramatic loss in accentuated antagonism in cardiac autonomic tone following HU deconditioning (33). Interestingly, although there are few well-designed studies that have systematically evaluated the arrhythmogenic risk to astronauts during microgravity, numerous anecdotal reports of arrhythmogenic events during spaceflight exist (14, 16, 23). Of particular relevance is the observation that many of these arrhythmic events during spaceflight have occurred at times of stressful maneuvers. This suggests that the sympathetic stress imposed upon the deconditioned heart may be particularly arrhythmogenic.

Although the cellular mechanisms responsible for increased arrhythmogenesis downstream to a loss in cardiac autonomic balance are not well understood, one possible mechanism could include an alteration in the expression and phosphorylation status of the gap junction protein connexin 43 (Cx43). Cx43 is a 43-kDa protein expressed primarily within mammalian ventricles at the intercalated discs and ensures efficient cell-to-cell electrical coupling (8, 22, 24). Significant alterations in the expression of Cx43 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ventricular arrhythmias following infarction (51) and heart failure (1, 2). Similarly, changes in the phosphorylation of Cx43 has been found to significantly alter propagation of cardiac action potentials and increase arrhythmogenesis in a number of pathological states (8) including cardiomyopathic heart failure (44) and myocardial ischemia (54). In addition, data indicate that states in which changes in cardiac autonomic tone may occur, such as that following chronic exercise training and vagus nerve stimulation, may alter the expression and phosphorylation of Cx43 (4, 7, 59, 60). Therefore, in the current study we hypothesized that reduced cardiac sympathovagal imbalance produced through the course of HU would result in increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias and significantly alter left ventricular (LV) Cx43 expression and/or phosphorylation. To test this hypothesis we examined the incidence of spontaneously occurring cardiac arrhythmias as well as those induced in response to a sympathetic pharmacological and behavioral stressor. Additionally, we measured the expression and phosphorylation status of LV-Cx43 in male Sprague-Dawley rats following HU or control condition. Our data indicate that HU results in increased predisposition to ventricular arrhythmias during an acute sympathetic/behavioral stressor and significantly increases the expression of LV-Cx43, likely of the phosphorylated form.

METHODS

General Experimental Design

Two sets of experiments were performed to test the central hypothesis that HU would result in an increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias and alter the expression of LV-Cx43. In experiment 1, rats (n = 12) were randomly assigned to the casted control (CC; n = 6) or HU (n = 6) condition. Rats were implanted with radiotelemetry probes, and the spontaneous arrhythmias that occurred during the 10- to 14-day CC or HU period as well as the arrhythmogenic effects in response to a sympathetic stressor following CC and HU were measured and compared between groups.

In experiment 2, we conducted control (n = 2) experiments validating the use of the polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies to detect the expression and phosphorylation status of Cx43. To avoid the confounding effects of isoproterenol (Iso) administration in experiment 1, in a separate group of rats (n = 10) randomly assigned to CC (n = 5) and HU (n = 5) groups we probed lysates with these antibodies specific to the unphosphorylated form of Cx43.

Animals

A total of 24 individually housed male, Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g) were used for the experimental procedures. Food (Teklad Laboratory Diet, Harlan Laboratories) and water were available ad libitum during the experiments. Temperature was maintained at 22 ± 2°C, and the light cycle was held at 12:12 with lights on at 0600. Rats were allowed at least 1 wk to acclimate to the surroundings before any experimental manipulations. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by Des Moines University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hindlimb Unloading Procedure

Hindlimb unloading was induced through elevation of the hindlimbs with a harness attached to the proximal two-thirds of the tail by techniques previously described (32). Briefly, two hooks were attached to the tail with moleskin adhesive material. A curved rigid support made of lightweight plastic (X-lite splint, AOA/Kirschner Medical, Timonium, MD) was placed beneath the tail to allow adequate blood flow. The hooks were connected by a wire to a swivel apparatus at the top of the cage, and the hindlimbs were elevated so there was no contact with supportive surfaces. Rats were maintained in a suspension angle of ∼30–35°. A small thoracic cast made from plaster of Paris was applied to reduce lordosis and help prevent the rats from reaching the tail apparatus. Casted control rats had thoracic casts applied and were singly housed but maintained in a normal cage environment. Hindlimb unloaded rats were adapted to the cage apparatus by temporarily suspending animals with a piece of athletic tape attached to the proximal tail for 1–2 h, 2–3 days before full instrumentation. Animals remained in the HU or CC conditions for 10–14 days, with the exception of temporary reloading onto the hindlimbs for 30 min per day. Casted control rats were handled an equal amount of time to control for time HU rats interacted with the experimenters. Body weights were recorded before and after the control or HU period. During the unloading protocol, the rats were monitored twice daily for adequate food and water intake, grooming behavior, and urination and defecation. Body weight was monitored on the seventh day of the HU protocol to ensure that animals were not experiencing excessive loss of body weight. Identical procedures were used for eliciting HU in all three sets of experiments.

Telemetry Implantation

Animals were surgically implanted with a radiotelemetry probe (C50-PXT; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) to record the electrocardiocardiogram (ECG), heart rate (HR), and mean arterial pressure (MAP). Surgical procedures were performed using aseptic technique under isoflurane anesthesia. Via a midline laparotomy, blood flow through the abdominal aorta was briefly halted, and the nonoccluding catheter of the blood pressure transducer was advanced into the abdominal aorta via a small puncture into the aorta with a 16-gauge needle. The blood pressure catheter was secured with an n-butyl cyanoacrylate adhesive (Vetbond; 3M, St. Paul, MN) and a cellulose patch. The bipolar ECG leads were tunneled subcutaneously and fixed in a lead II configuration by suturing the bare ends of each lead to the right pectoral muscle and lateral abdominal wall, respectively. The transmitter was sewn to the abdominal wall, and all incisions were closed with sterile skin staples (9 mm Auto Clips, MikRon Precision; Gardena, CA). Immediately following surgery rats were given antibiotics (ampicillin, 200 mg/1 kg im; and Baytril 10 mg/kg im), analgesics (Butorphenol, 1 mg/kg im; or Rimadyl, 5 mg/1 kg sc), and lactated Ringer solution, USP (3–5 ml sc; B Braun Medical, Fisher Scientific). Antibiotic ointment was also applied to all incision sites. Rats were placed on a heat source during acute surgical recovery. Rats were checked daily to ensure they were eating, drinking, and had adequate urination and defecation. All incision sites were checked daily. Staples were removed 7–10 days after surgery, and antibiotic ointment was applied to the skin.

Animals were given at least 14 days to recover from surgical procedures before further manipulation.

Spontaneous Arrhythmia and Electrocardiographic Parameter Measurement

Radiotelemetry data were collected at a sampling speed of 1,000 Hz for 5 min each hour over a 48-h period. This collection occurred during four specific time periods over the HU or CC protocol. These four time periods included: 1) a 48-h baseline (BL) recording started 14 days after radiotelemetry implantation and before any experimental manipulation, 2) first 48 h of HU/CC condition (Early), 3) a 48-h mid-HU/CC recording (Mid) recording took place on days 6 and 7 in the HU/CC protocol, and 4) a 48-h late HU/CC recording (Late) recording was collected during the last 48 h the animal was in the 10- to 14-day HU/CC protocol. Spontaneously occurring cardiac arrhythmias were identified and scored according to scoring methods stated below. To standardize the observation times in all animals, spontaneous arrhythmias were quantified as the arrhythmic index as defined below. ECG data for the measurement of basic ECG parameters were obtained in the normal posture at baseline and at the conclusion of the 14-day protocol in the normal posture at the same relative time during the day in both groups of animals.

Cardiac Arrhythmia Provocation

The arrhythmogenic response to an acute sympathetic stressor was measured in all rats through administration of the nonspecific β-adrenergic agonist Iso immediately followed by brief handling/restraint. Before the stress test, rats were removed from the HU or CC cage environment and placed in the normal posture in a separate recording cage on a telemetry receiver. After a 30-min acclimation, baseline parameters were recorded continuously for a period of 10 min. Iso was then injected subcutaneously (150 μg/kg). Fifteen minutes after Iso administration, rats were subjected to a brief handling/restraint procedure by placing the animals in a small Plexiglas holder for 1 min. After the brief restraint there was a 10-min postrecording. Throughout the experiment the ECG and arterial blood pressure were continuously monitored. After the stress test, rats were euthanized by an overdose of anesthetic (4% isoflurane), and the soleus muscles were dissected free from the hindlimb weighed and “flash” frozen in liquid nitrogen for later measurement of citrate synthase activity. A thoracotomy was performed to ensure complete euthanasia.

Citrate Synthase Activity

At the conclusion of the HU or CC protocol, frozen soleus muscles obtained from the rats included in experiment 1 were homogenized in 19 volumes KPO4 buffer, sonicated, and centrifuged to extract citrate synthase from the whole muscles. Citrate synthase activity was measured by a colorimetric assay using 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoate) as a substrate, according to the method of Serre (47). Absorbance at 412 nm was used to calculate citrate synthase activity (in μmol·g−1·min−1).

Left Ventricular Cx43 Expression Measurements

LV Cx43 protein was quantified by Western blot analysis. After the experimental protocol, rats were deeply anesthetized with 4% isoflurane. The chest wall was opened and the beating heart was removed and placed in 0.9% saline solution to prevent clots from forming. The heart was then rapidly dissected to isolate the LV, which was weighed and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Pulverized frozen samples of the LV were homogenized in a lysis buffer referred to as +PI buffer [containing 10 mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM disodium EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.3 mM PMSF, and 1:200 protease inhibitor cocktail from Sigma]. Homogenates were then sonicated at 17–19 watts on ice for 1 min, 3 times with a 2-min rest between each sonication. The homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at 21,000 g at 4°C.

After centrifugation the pellet was discarded and supernatants were then recentrifuged for another 30 min at 21,000 g at 4°C. Once again the pellet was discarded and the protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Protein samples (25 μg) were then separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with a 5% milk blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. After the block was completed, the membrane was then incubated with rabbit anti-Cx43 antibody (lot no. 683982A, Invitrogen Polyclonal-Cx43) diluted 1:1,000 in 5% milk blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Blots were then incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (H+L, Promega, Madison, WI) diluted 1:5,000 in 5% milk blocking buffer. Protein expression was then visualized and imaged (Molecular Image ChemiDoc XRS Imaging System, Bio-Rad) by adding chemiluminescence reagent (Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) to the membranes. To control for loading, samples were also probed with an ERK2 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:5,000 in 5% milk using the same methods described above.

With the use of a modified version of the protocol above, the phosphorylation status of LV Cx43 protein was assessed using a monoclonal antibody directed against the unphosphorylated form of Cx43 at Ser368 (36). Pulverized frozen samples of the LV were homogenized in either the +PI buffer or a modified buffer, designated −PI [containing mM 10 Tris, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaCl, 0.3 mM PMSF, and 1:200 protease inhibitor cocktail from Sigma], which lacked the phosphatase inhibitors sodium pyrophosphate, NaF, and sodium orthovanadate. To determine the specificity of the monoclonal antibody to detect unphosphorylated Cx43, −PI-extracted samples were treated with 2 μl of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (+CIP) (New England BioLabs). Protein samples (50 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with either an anti-Cx43 polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) diluted 1:1,000 in 5% milk blocking buffer or mouse anti-Cx43 monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen) diluted 1:500 in 5% milk blocking buffer. Previous studies have shown anti-Cx43 polyclonal antibody recognizes both the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of Cx43 (5, 6), while anti-Cx43 monoclonal antibody is specific for an unphosphorylated form of Cx43 (36). Use of these anti-Cx43 antibodies allowed for distinguishing between phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of Cx43.

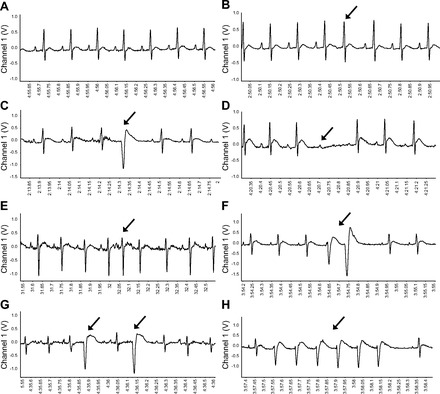

Electrocardiographic Analysis, Cardiac Arrhythmia Identification, and Scoring

Baseline and post-HU ECG parameters of PR interval, QRS duration, and the QT interval duration corrected to HR (QTc) via Bazett's formula were measured using PowerLab ECG data analysis extension. Arrhythmias occurring spontaneously at BL, Early, Mid, and Late time periods during the HU and CC protocol, as well as in response to an acute sympathetic stressor, were identified and compared. Arrhythmic events were identified according to the Lambeth Convention guidelines (57) and quantified using a modification of a scoring system previously described (25) (Fig. 1). Arrhythmias were assigned a score of 0 (sinus complex) to 4 based on the level of severity for purposes of quantification and statistical comparison. The following arrhythmic events were given a score of 1: premature supraventricular beat (PSVB), isolated premature ventricular complex (PVC), and atrioventricular (AV) block. Atypical or absent P waves along with irregularly spaced R waves were defined as PSVB (Fig. 1B). Isolated and identifiable premature QRS complexes (premature in relation to the cardiac cycle) were defined as PVCs (Fig. 1C). AV block was identified as a sinus originating P wave in the absence of a following QRS complex (Fig. 1D). The following arrhythmic events were given a score of 2: supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and salvo. Atypical or absent P waves, normal width QRS complexes, and increased HR for three or more consecutive complexes were markers of premature supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) (Fig. 1E). Two or three consecutive PVCs were termed salvo (Fig. 1F). A score of 3 was assigned to the following arrhythmic events: bigeminy, ventricular tachycardia (VT), and sustained supraventricular arrhythmias. Bigeminy was characterized by alternating PVCs and sinus complexes (Fig. 1G). Ventricular tachycardia was defined as a run of four or more consecutive PVCs (Fig. 1H). Sustained supraventricular arrhythmias were defined as >10 consecutive supraventricular events. Sustained ventricular tachycardia (>10 consecutive premature ventricular beats) and ventricular fibrillation were assigned a score of 4.

Fig. 1.

Identification and scoring of spontaneous and provoked arrhythmias. Examples of normal sinus rhythm (A) (NSR = 1), premature supraventricular beat (PSVB = 1) (B), isolated premature ventricular complex (PVC = 1) (C), atrioventricular (AV = 1) block (D), supraventricular tachycardia (SVT = 2) (E), salvo = 2 (F), bigeminy = 3 (G), and ventricular tachycardia (VT = 3) (H). Arrows denote arrhythmic event.

Arrhythmic indices were defined and computed as follows. 1) Arrhythmic score: after each arrhythmic event was identified and quantified, an arrhythmic score was calculated by taking the score times number of arrhythmic events for that arrhythmia. 2) Arrhythmic burden: from the arrhythmic score the arrhythmic burden for each observation period was calculated. The arrhythmic burden was defined as the sum of the arrhythmic scores occurring over the observation period. 3) Arrhythmic index: to standardize the number of arrhythmias by the observation time, an arrhythmic index was calculated by taking the arrhythmic burden and dividing this number by the total minutes analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as means ± SE. The mean arrhythmic index was calculated for each group and statistical compared between groups for the BL, Early, and Late time periods of the HU/CC protocol using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Mean electrocardiographic parameters measured at baseline pre- and post-HU were compared using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Mean values of the arrhythmic index for supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias were calculated within each group for BL, Early, Mid, and Late time periods. These values were then summed within each group to give a total supraventricular arrhythmic index and total arrhythmic ventricular index for each group over the HU/CC protocol. The total supraventricular index and total ventricular arrhythmic indices were statistically compared between the CC and HU groups using a two-way ANOVA.

Mean values of HR, MAP, and SDNN during the 10-min baseline period in the normal posture were statistically compared between the HU and CC groups using independent t-tests. Mean values of HR, MAP, arrhythmic burden, and arrhythmic index were calculated within each group for the BL, Iso administration, and brief handling/restraint (BR) time frames of the acute stress test. Data were statistically compared between the HU and CC groups by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Within each group the mean values for the total arrhythmic burden, supraventricular arrhythmic burden, and ventricular arrhythmic burden at BL, Iso, and BR were summed to give a total arrhythmic burden, total supraventricular arrhythmic burden, and total ventricular arrhythmic burden for each group. These data were statistically compared between the HU and CC animals by independent t-tests.

Changes in body weight were compared using two-way ANOVA with repeated measure design. Western blot densitometric data, soleus wet weights, muscle weight-to-body weight ratios, whole heart weights, and LV weights were compared between the HU and CC groups by independent t-tests. When ANOVA indicated significant primary effects of an intervention or a significant interaction a Tukey's post hoc analysis of significant effects was performed. For all statistical analyses, a probability of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Experiment 1

Hindlimb unloading.

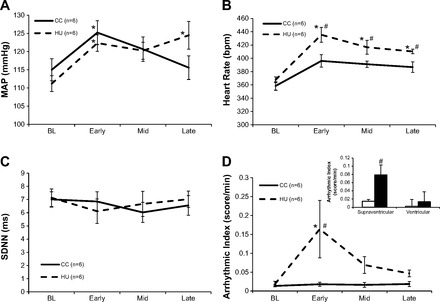

The changes in MAP, HR, and SDNN at baseline before the 14-day protocol and then during the 14-day HU protocol are shown in Fig. 2. Data indicate that baseline MAP, HR, and SDNN were not different between the groups when measured in the normal posture before the 14-day protocol. However, both MAP and HR were significantly elevated in both groups of rats during the early time point, whereas HR remained elevated during the protocol and was significantly higher than CC rats. Although MAP was elevated above baseline in HU rats at both the early and late time point, it was not different between groups at either of these time points. The SDNN was not different between the groups throughout the 14-day protocol while animals were in the unloaded position.

Fig. 2.

Data comparing the changes in cardiovascular parameters and spontaneous arrhythmias in casted control (CC) (n = 6) and hindlimb unloading (HU) (n = 6) groups during the 14-day protocol. A: changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP) in CC and HU animals over the baseline (BL), Early, Mid, and Late time points. B: changes in heart rate (HR) in CC and HU animals over the BL, Early, Mid, and Late time points. C: changes in the standard deviation of the normal-to-normal R-to-R interval duration (SDNN) in CC and HU animals over the BL, Early, Mid, and Late time points. D: arrhythmic index (arrhythmic burden/min). Changes in spontaneous arrythmias in CC and HU animals over the BL, Early, Mid, and Late time points are shown. The HU group had a higher incidence of spontaneous arrhythmias at the Early time point compared with their BL and the CC group. Inset: total supraventricular arrhythmic index and total ventricular arrhythmic index in CC and HU animals over BL, Early, Mid, and Late. There was a greater incidence of spontaneous supraventricular arrhythmias in the HU group compared with the CC group over the protocol and a trend toward a higher incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in the HU animals compared with the CC (P = 0.10) . *P < 0.05 vs. BL within group, #P < 0.05 vs. CC at same time point.

Baseline cardiovascular parameters, body weight, soleus muscle weights, and soleus citrate synthase activity recorded from the rats included in experiment 1 after the 14-day protocol are shown in Table 1. Body weight significantly increased in CC rats and significantly decreased in HU rats during the protocol. In addition, a significant atrophy resulted from the deconditioning protocol in HU rats as evidenced by a lower absolute and relative wet weight of the soleus and plantaris hindlimb muscles compared with CC counterparts. Hindlimb unloading also resulted in a significantly lower citrate synthase enzymatic activity in the soleus muscle compared with CC rats indicating lower oxidative capacity following deconditioning. Baseline cardiovascular data obtained in the normal posture immediately following the 14-day protocol indicate that HU resulted in a significant resting tachycardia. This tachycardia was further elevated from that measured in the head-down posture. In addition rats had elevated MAP and reduced HRV as well as a lower SDNN compared with the CC group in the normal posture. These findings verify both cardiovascular and musculoskeletal deconditioning following HU, and highlight the cardiovascular adjustments that occur when animals go from a suspended (unloaded, head-down posture) (Fig. 2) to resumption a normal posture (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline cardiovascular parameters, body weight, hindlimb muscle weight, and soleus citrate synthase activity from rats in experiment 1

| Body Weight, g |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR, beats/min | MAP, mmHg | SDNN, ms | Pre-HU/CC | Post-HU/CC | Soleus Wt Post-HU/CC, mg | Soleus/BW, mg/g | Soleus Citrate Synthase, μmol·g−1·min−1 | |

| CC | 379 ± 7 | 117 ± 4 | 5.99 ± 0.77 | 327 ± 9.76 | 353 ± 13.5* | 144 ± 11 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 17.4 ± 1.6 |

| HU | 476 ± 9† | 131 ± 3† | 4.06 ± 0.30† | 329 ± 10.4 | 308 ± 8.11*† | 88.3 ± 0.2† | 0.29 ± 0.01† | 13.3 ± 1.6† |

Values are means ±SE; n = 6 rats. Heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and the SD of the normal-to-normal HR interval (SDNN) were measured during 10 min of normal weight-bearing posture following the hindlimb unloaded (HU) and casted control (CC) protocol. Body weight (BW) was measured pre- and post-HU or CC condition. All other variables were measured Post-HU/CC.

P < 0.05 vs. Pre within group,

P < 0.05 vs. CC.

Electrocardiography and spontaneous arrythmias.

Baseline and post-HU ECG parameters were measured in both groups of rats. Data indicate that while there were no differences in baseline ECG parameters between groups, HU resulted in a significantly shortened PR interval, while the QTc increased in both groups over the 14-day protocol (Table 2). Spontaneously occurring arrhythmias were identified and scored at BL and at three different time points during the CC and HU protocol (Fig. 2). Since we were not able to obtain identical observation times for all animals, the arrhythmic index was used to compare the arrhythmic burden between groups. Data indicate that while both groups of rats were virtually free from arrhythmias at baseline, there was a significant increase in the number of spontaneous arrhythmias sustained by HU rats during the first 48 h (Early) of the protocol as indicated by a significantly higher arrhythmic index for HU rats during this time point (Fig. 2D). These spontaneous arrhythmias largely resolved during the HU intervention as there were no significant differences in the arrhythmic index at the Mid (days 6–7) or Late (last 48 h) time points of the protocol. When the total arrhythmic index over all time points was combined and categorized, data indicate that HU rats had a significantly greater incidence of supraventricular arrhythmias during the HU intervention with a trend toward an increase in ventricular arrhythmias (Fig. 2D, inset).

Table 2.

Baseline electrocardiographic parameters before and after HU or CC condition

| PR Interval, ms | QRS Duration, ms | QTc Interval, ms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Pre-HU | |||

| CC | 46 ± 1.1 | 18.9 ± 1.1 | 144 ± 7.4 |

| HU | 45 ± 1.2 | 16.4 ± 1.3 | 142 ± 12 |

| Baseline Post-HU | |||

| CC | 45 ± 1.2 | 18.8 ± 2.3 | 160 ± 6.8† |

| HU | 40 ± 0.7*† | 17.6 ± 1.6 | 168 ± 9.4† |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6 rats. HU/CC.

P < 0.05 vs. CC,

P < 0.05 vs. Pre-HU time point within respective group.

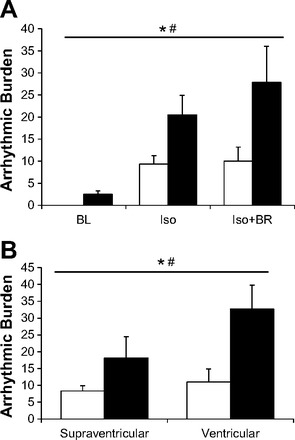

Cardiac arrhythmia provocation.

The arrhythmogenic response to a sympathetically induced pharmacological and behavioral stressor in HU versus CC rats in the normal posture following the 14-day protocol is shown in Fig. 3. Since identical observation periods were utilized among all rats, the arrhythmic burden was used to compare these responses. Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures indicate a significant group and stressor effect, thus HU rats sustained significantly more cardiac arrhythmias during all three time points, and there was a progressive increase in arrhythmic burden from baseline to Iso administration and then with the addition of brief restraint (Fig. 3A). It is interesting to note that when brief restraint was administered, the arrhythmic burden increased further in HU rats, whereas this behavioral stressor did not initiate any further arrhythmogenesis in the CC group. Further statistical analysis of the classification of the arrhythmic burdens over these time periods revealed a significantly greater group effect in HU rats as well as a significantly more ventricular than supraventricular arrhythmias during these stressors (Fig. 3B). Figure 4 illustrates the analysis of the number (Fig. 4A) and frequency (Fig. 4B) by classification of arrhythmic events. The type of event is arranged according to the severity for baseline (Fig. 4B, top), Iso (middle), and Iso + BR (bottom). These data indicate that there was a generalized increase in the number and frequency events in HU versus CC rats as well as a shift toward more severe arrhythmias during Iso + BR.

Fig. 3.

Data comparing the arrhythmic burden and arrhythmic index over the BL, isoproterenol (Iso), and Iso + brief handling/restraint (Iso + BR) periods. A: there were significant main effects of group and stressor on the arrhythmic burden, thus HU rats had significantly more arrythmias than CC rats for all three stressors. *P < 0.05 Significant main effect for group; #P < 0.05 significant main effect for stressor. B: classification of arrhythmias during the acute stressors. There was a significant main effect for group and for category of arrhythmias. Thus HU rats had significantly more ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias during the acute stressors. *P < 0.05 significant main effect for group; #P < 0.05 significant main effect for category of arrythmia.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the classification of the number of arrhythmic events (A) and frequency (B) of the arrhythmic events during baseline (top), Iso administration (middle), and Iso + BR (bottom) for each category of arrhythmia analyzed in relation to the severity or score (as identified in Fig. 1). Data indicate that there was an increase in the frequency of all events in HU versus CC rats and a shift toward more severe arrhythmias during Iso + BR compared with other stressors.

Taken together these data confirm our original hypothesis that HU would result in an increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias during an acute stressor. Additionally, it appears that the increased arrhythmic risk following deconditioning is largely driven by an increase in the predisposition to more severe ventricular rhythms.

Hemodynamic response to sympathetic stressors.

The HR and blood pressure response at baseline, following administration of Iso, and the addition of BR are illustrated in Fig. 5. As shown in Table 1, HU rats had a significantly elevated HR and MAP during the 10-min BL observation period, whereas administration of Iso elicited a dramatic tachycardia and hypotensive response in both groups of rats with no significant differences between the CC and HU rats observed. Upon administering BR, the hypotensive response to Iso was largely reversed in the HU but not CC rats as evidenced by a significantly higher absolute MAP response to BR in the HU rats. Thus the addition of this behavioral stressor likely evoked peripheral sympathetic stimulation of a level sufficient to increase total peripheral resistance in the HU rats. There were no additional increases in the HR response to BR and no differences in the absolute HR during BR between groups.

Fig. 5.

Data comparing heart rate (bpm) and MAP (mmHg) over the BL, Iso, and Iso + BR periods during the acute sympathetic stressor. A: BL HR was elevated in the HU animals. There was a significant main effect of Iso and BR on HR compared with BL. B: MAP was elevated in the HU at BL and BR compared with the CC MAP. There was a significant main effect of Iso on MAP compared with BL and significant main effect of BR on MAP compared with the BL and Iso MAP. *P < 0.05 vs. BL, #P < 0.05 vs. Iso, @P < 0.05 vs. CC at same time point.

Experiment 2

Hindlimb unloading.

The effects of HU on body weight, soleus muscle weight, and cardiac weight from rats included in experiment 2 are shown in Table 3. Data indicate that HU rats in this experiment underwent deconditioning to a nearly identical extent as evidenced by significant reduction in both the absolute and relative soleus muscle weights. Additionally, there were no significant differences in either absolute whole or LV heart wet weight, as well as no significant difference between the groups with respect to heart weight-to-body weight ratios or LV-to-body weight ratios.

Table 3.

Body weight, hindlimb muscle weight, and heart weight from rats in experiment 2

| BW, g |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-HU/CC | Post-HU/CC | Soleus Wt Post-HU/CC, mg | Soleus/BW, mg/g | Whole Heart Wt, g | Heart/BW, mg/g | LV Weight, mg | LV/BW, mg/g | |

| CC | 277 ± 6.4 | 297 ± 13.5* | 134 ± 9.1 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 2.94 ± 0.06 | 644 ± 21 | 2.17 ± 0.05 |

| HU | 291 ± 7.3 | 282 ± 1.2 | 93.4 ± 4.3† | 0.33 ± 0.02† | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 3.04 ± 0.05 | 646 ± 13 | 2.29 ± 0.05 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 5 rats. Body weight (BW) was measured pre- and post-HU or CC condition. All other variables including heart and left ventricular (LV) weight were measured Post-HU/CC.

P < 0.05 vs. Pre within group,

P < 0.05 vs. CC.

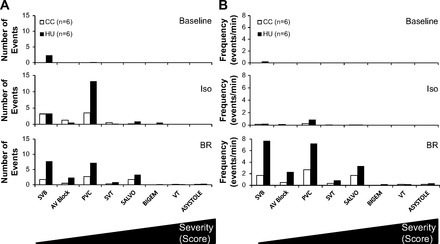

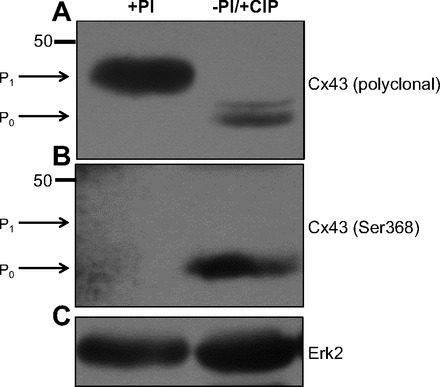

Specificity of Cxn43 antibodies.

Control experiments validating the specificity of our chosen Cx43 antibodies in Sprague-Dawley rats are shown in Fig. 6. Cx43 was extracted from the LV of control rats using either a detergent-based buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors (+PI) or detergent-based buffer containing no phosphatase inhibitors (−PI). Extract from −PI samples were further treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (+CIP) to ensure dephosphorylation of Cx43 proteins. Subsequently, Western blot analysis was performed with an anti-Cx43 polyclonal antibody that recognizes total Cx43 (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) and an anti-Cx43 monoclonal antibody (Cx43 Ser 368) that recognizes an unphosphorylated form of Cx43. Lysis in the +PI buffer revealed a dominant band at 43 kDa (P1) in Fig. 6A (phosphorylated Cx43) and no detectable band in Fig. 6B (unphosphorylated Cx43). In contrast, −PI/+CIP conditions resulted in a dominant band at 41 kDa (P0), which represents dephosphorylated Cx43 and is observed when probing for total Cx43 or Cx43 Ser368 (36). With the use of ERK2 as a loading control, no detectible differences in expression between the two conditions were observed (Fig. 6C). These data provide evidence that the different migrating patterns of the Cx43 protein are due to differences in the phosphorylation status of Cx43, and that Cx43 in different phosphorylated forms can be detected through the use of a monoclonal antibody and polyclonal antibody chosen for these experiments.

Fig. 6.

Western blot analysis of the 43-kDa gap junction protein connexin 43 (Cx43) from the hearts of two control rats lysed in either +PI or −PI buffer. Lysate in the −PI buffer was further treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP). After SDS-PAGE, membranes were probed with anti-Cx43 polyclonal (A) or monoclonal antibody (Ser368) (B) to demonstrate differences in phosphorylation status of Cx43. As a control for loading, membranes were probed for ERK2 (C).

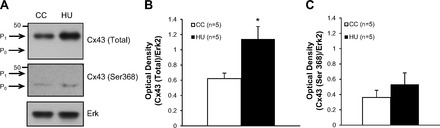

Left ventricular Cx43 expression.

The effects of HU on the expression of LV-Cx43 from rats included in experiment 2 are shown in Fig. 7. Again, lysate from the LV in HU (n = 5) and CC (n = 5) rats included in experiment 2 were subjected to Western blot analysis. A representative set of blots is shown in Fig. 7A. These findings suggest a higher level of total Cx43 expression in the HU animals compared with the CC animals at the P1 position. Membranes probed with ERK2 (loading control) showed no difference in expression between the groups. Densitometric analysis demonstrates a significant increase in the expression of LV-Cx43 in HU versus CC animals (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Western blot analysis of the 43-kDa gap junction protein Cx43 from the hearts of a separate group of CC (n = 5) and HU (n = 5) rats. A: representative blot from one CC and one HU rat. After SDS-PAGE, membranes were probed with an anti-Cx43 polyclonal to quantify the total Cx43 expression (top), or monoclonal antibody to quantify the expression of unphosphorylated Cx43 (Ser368) (middle). As a control for loading, membranes were probed for ERK2 (bottom). B: mean data indicating significantly higher total Cx43 expression in HU vs. CC rats. C: mean data indicating no significant difference in unphosphorylated Cx43 expression in HU vs. CC rats. *P < 0.05.

Since the migration of this single band appears to be such that it corresponds to the phosphorylated form of Cx43, to further explore this possibility we probed with a monoclonal antibody specific to the unphosphorylated form of Cx43, which recognizes the unphosphorylated Ser368 residue. Results show very little unphosphorylated Cx43 expression (P0) in both CC and HU rats (Fig. 7A, middle), and the mean data confirm this result indicating no significant difference between the groups (Fig. 7C). Taken together these results confirm our original hypothesis in that HU resulted in a significant change in the expression and phosphorylation of LV-Cx43, specifically resulting in an increased expression of phosphorylated Cx43 and no detectable difference in levels of unphosphorylated Cx43.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we examined the hypothesis that HU would result in increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias and alter the expression and phosphorylation status of the gap junction coupling protein Cx43. Confirming our hypothesis, HU resulted in increased ventricular arrhythmogenesis in response to acute stressor, and furthermore, we observed that HU results in an increase in the expression of Cx43, most likely of the phosphorylated form. These findings suggest that the cardiac autonomic imbalance that occurs in response to cardiovascular deconditioning results in an increased risk for sustaining cardiac arrhythmias, most notably during a behavioral stressor in the face of sympathetic activation. In addition, HU results in an alteration in the expression and phosphorylation status of Cx43, which not only provides insight into the cardiac adjustments following deconditioning, but may provide a model for new insights regarding the regulation and phosphorylation of Cx43 expression in the pathophysiology of cardiac arrhythmogenesis in the absence of ischemia or LV hypertrophy.

Previous results indicate that through the process of adaptation to HU, rats develop a pronounced cardiac autonomic imbalance (33, 35). Increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias in the face of sympathovagal balance has been well described in both human and animal models (3, 53, 55). Accordingly, we hypothesized that the cardiac autonomic imbalance following HU would confer increased risk for sustaining cardiac arrhythmias. In the current study we found that HU rats did sustain a greater number of spontaneous cardiac arrhythmias; however, these were primarily of supraventricular origin and occurred primarily during the early adjustments to HU. Although the mechanisms that triggered these supraventricular events is speculative, a number of neurohumoral adjustments are occurring during the first 48 h of HU (50), including cardiopulmonary activation (30, 37), diuresis, and natriuresis (12), and thus may involve one of these factors. The arrhythmic index returned to baseline by the last 48 h of the HU intervention, further supporting that these arrhythmic events were related to these early adjustments to HU. It may also be possible that compensatory changes in Cx43 expression and phosphorylation occurred early during HU. Future studies addressing the time course of changes in Cx43 expression would be necessary to determine whether compensatory adjustments in Cx43 are responsible for the resolution of these arrhythmias.

Our data indicate that HU rats experienced a significantly greater number of cardiac of ventricular arrhythmias, most notably during the combined pharmacological and behavioral sympathetic stressor (Figs. 3 and 4). Iso administration was effective at provoking cardiac arrhythmias in both groups with a trend toward a greater arrhythmic burden in the HU rats, although this effect did not reach statistical significance. However, upon administering an additional behavioral stressor through BR, while we observed that this maneuver was highly arrhythmogenic in the HU rats, there was no further increase in the arrhythmic burden in CC rats (Fig. 3). This finding may indicate that the HU rats have a greater sympathetic response to behavioral stress. This possibility is supported by the finding that upon administration of the BR, the reversal of the hypotensive response to Iso was much greater in the HU versus CC rats (Fig. 5, top). It is possible that the HU rats have a greater behavioral vulnerability to stress, which would be supported by our previous findings that HU rats display anhedonia, a central feature of psychological depression, following 14 days of deconditioning (33). This effect likely imposed a greater hemodynamic burden, since mean arterial pressure was higher in HU rats, while HR was not different during the BR, thus resulting in a higher rate pressure product in HU rats. This could contribute to a higher afterload and thus a higher myocardial oxygen demand increasing the arrhythmic response in HU rats. In addition these findings corroborate with anecdotal data obtained from astronauts during spaceflight. Although there are few studies that have systematically evaluated astronauts' predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias during microgravity, one such study (40) found that there was no significant increase in the number of ventricular or supraventricular events during extravehicular activity during spaceflight; however, there have been several reports regarding incidents of ventricular arrhythmias in astronauts during spaceflight (16, 23). Additionally, there is evidence from studies using a ground-based model of spaceflight in humans indicating a greater increase in microvolt T-wave alternans, (17) as well as increased QT variability (41), both electrocardiographic evidence of repolarization heterogeneity that is associated with arrhythmic risk. Data from our study indicates that 14 days of HU resulted in significantly shortened PR interval in the absence of any change in QRS duration. This effect is likely due to heightened sympathetic activation in HU rats immediately following the HU intervention (29) and would corroborate with both the tachycardia, reduced SDNN, and previous findings indicating HU results in cardiac sympathovagal imbalance (33). The QT interval duration corrected for elevated HR (QTc) was not different between groups but increased in both HU and CC rats following the 14-day protocol, perhaps reflective of changes due to growth or maturation. Our findings further support the notion that the cardiac sympathovagal imbalance following cardiovascular deconditioning increases cardiac arrhythmogenic risk.

Although the cellular mechanisms that mediate the increased predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias in response to cardiac sympathovagal balance are not well understood, one possibility we wanted to explore is that an alteration in LV-Cx43 expression and phosphorylation status may play a role. To investigate this possibility, our experimental design necessitated using a separate group of rats to avoid the confounding effects of Iso, as administration of this drug is a method used to induce heart failure (10). Thus we measured Cx43 expression in a separate group of HU and CC rats to determine the Cx43 expression status in the heart following deconditioning at a point before which an acute stressor would be induced. Data indicate that this second group of rats used in experiment 2 (Table 3) was deconditioned nearly identically to those rats used in experiment 1 (Table 1).

In general it is thought that reduced phosphorylation and expression of Cx43 results in reduced cell-to-cell electrical coupling of cardiomyocytes and promotes arrhythmic potential (6). However, data indicate that increased expression of Cx43 following myocardial ischemia can occur, specifically when myocytes couple to myofibroblasts through Cx43 (54). In addition, heart failure following cardiomyopathy in hamsters results in increased arrhythmogenesis and increased expression of phosphorylated Cx43 at Ser255 residues. We found that HU resulted in increased expression of Cx43 at the band that migrates consistent with phosphorylated Cx43 (45).

Furthermore, we found that there was low expression in unphosphorylated Cx43 in both CC and HU rats with no significant difference between these groups when we probed the lysate with an antibody directed against an unphosphorylated Ser368 residue (Fig. 7). Control studies (Fig. 6) indicate that this antibody is specific to the unphosphorylated form of Cx43 since forced dephosphorylation of lysates by removing phosphatase inhibitors and adding calf intestinal phosphatase results in a high level of Cx43 detection with an antibody specific to unphosphorylated Ser368 as well as an increased mobility using SDS-PAGE consistent with unphosphorylated Cx43 (6, 36). When lysates generated in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors are probed with an antibody for total Cx43, we found a decreased mobility using SDS-PAGE and expression patterns consistent with phosphorylated Cx43, confirming previous findings (6, 36). This is the same migration pattern we observed when probing for total Cx43 in HU versus CC lysates. Taken together we interpret these findings that HU results in increased expression of phosphorylated Cx43.

Although these findings seem counter to the general idea that reduced expression and phosphorylation of Cx43 is associated with increased arrhythmogenesis, there are several possible explanations for these results. First, most previous studies regarding the role of LV-Cx43 in the pathogenesis of cardiac arrhythmias have been largely conducted within the setting of acute ischemia, infarction, and heart failure and may not completely correspond to the pathophysiology of cardiovascular deconditioning produced during hindlimb unloading. Ischemia results in rapid dephosphorylation and uncoupling of cardiomyocytes (6); however, there is no evidence to indicate that HU rats have any ischemic cardiac disease at rest and in fact have very few spontaneous arrhythmias during the mid to late stages of HU (Fig. 2) or following removal from HU in the normal posture (Fig. 3). It is only when rats are subjected to an acute stressor do they develop ventricular arrhythmias. In addition HU rats displayed no signs of overt or subclinical signs of heart failure or cardiomyopathy, and there were no differences in the heart-to-body weight or LV-to-body weight ratios (Table 2), a finding consistent with previous studies (39). Second, although phosphorylation of Cx43 is generally thought to be cardioprotective and Cx43 requires phosphorylation to be correctly inserted within gap junctions of the intercalated disc of cardiomyocytes (27, 28), there is evidence to suggest that some phosphorylation sites, including Ser255 (28, 49) and Ser368 (13, 49), mark the protein for degradation and may play a pathogenic role in cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Furthermore, increased phosphorylation and expression of Cx43 has been documented to occur when cardiomyocytes couple with myofibroblasts (54) and in cardiomyopathic heart failure (44), supporting a role for upregulation of Cx43 expression and phosphorylation resulting in arrhythmic substrate under these pathological conditions.

Finally, this finding may be indicative of a compensatory upregulation of Cx43 expression. It is interesting to consider that perhaps HU rats would have had a greater arrhythmic burden if the changes in Cx43 expression did not occur. Previous studies have shown that β-adrenoreceptor activation increases the expression of Cx43 in a cell culture model, including findings indicating increased Cx43 mRNA (42). Since cardiac sympathetic tone increases during the process of HU (33, 35) and increased sympathetic tone has been well established to increase the arrhythmogenic potential of myocardium (42), this possibility is quite plausible. Future studies would need to be conducted to determine whether HU results in increased Cx43 mRNA or whether the increased expression is solely relegated to increased expression of phosphorylated Cx43 at more “pathological” residues.

Perspectives and Significance

Although it has been well established that cardiac autonomic imbalance increases the predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias (48, 56, 61), there is little hard mechanistic data at the cellular and molecular level linking these two observations. Data from the current study indicate that in the HU rat model, which has increased basal sympathetic tone and dramatically reduced parasympathetic tone (33, 35), there was an increase in the arrhythmic burden to sympathetic stressors and increased expression of Cx43, likely of the phosphorylated form. This raises the possibility that changes in Cx43 expression and phosphorylation status may be responsive to changes in cardiac autonomic tone and thus a mechanism responsible for the increased arrhythmogenic potential in the autonomically imbalanced heart. Furthermore, this suggests that cardiovascular deconditioning not only leaves the brain vulnerable to behavioral pathology, as we previously found these rats experience anhedonia (33), but also leaves the heart vulnerable to cardiac insult as well. These findings indicate that the HU is an excellent model in which to further explore the role of cardiac autonomic tone in the pathogenesis of behaviorally induced cardiac arrhythmia, as well as its role in the regulation expression and phosphorylation of Cx43 in a more novel pathological state.

GRANTS

Funding was provided through the Iowa Osteopathic Education and Research Fund.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.A.M. and M.K.H. conception and design of research; J.A.M., K.C.W., A.J.J., and E.R.G. performed experiments; J.A.M., M.K.H., K.C.W., A.J.J., and E.R.G. analyzed data; J.A.M. and M.K.H. interpreted results of experiments; J.A.M., M.K.H., K.C.W., and A.J.J. prepared figures; J.A.M. drafted manuscript; J.A.M., M.K.H., K.C.W., A.J.J., and E.R.G. edited and revised manuscript; J.A.M., M.K.H., K.C.W., A.J.J., and E.R.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Rachel M. Firkins for excellent technical assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ai X, Pogwizd SM. Connexin 43 downregulation and dephosphorylation in nonischemic heart failure is associated with enhanced colocalized protein phosphatase type 2A. Circ Res 96: 54–63, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akar FG, Nass RD, Hahn S, Cingolani E, Shah M, Hesketh GG, DiSilvestre D, Tunin RS, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF. Dynamic changes in conduction velocity and gap junction properties during development of pacing-induced heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1223–H1230, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson KP. Sympathetic nervous system activity and ventricular tachyarrhythmias: recent advances. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 8: 75–89, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ando M, Katare RG, Kakinuma Y, Zhang D, Yamasaki F, Muramoto K, Sato T. Efferent vagal nerve stimulation protects heart against ischemia-induced arrhythmias by preserving connexin43 protein. Circulation 112: 164–170, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beardslee MA, Laing JG, Beyer EC, Saffitz JE. Rapid turnover of connexin43 in the adult rat heart. Circ Res 83: 629–635, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beardslee MA, Lerner DL, Tadros PN, Laing JG, Beyer EC, Yamada KA, Kleber AG, Schuessler RB, Saffitz JE. Dephosphorylation and intracellular redistribution of ventricular connexin43 during electrical uncoupling induced by ischemia. Circ Res 87: 656–662, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellafiore M, Sivverini G, Palumbo D, Macaluso F, Bianco A, Palma A, Farina F. Increased cx43 and angiogenesis in exercised mouse hearts. Int J Sports Med 28: 749–755, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein SA, Morley GE. Gap junctions and propagation of the cardiac action potential. Adv Cardiol 42: 71–85, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bungo MW, Charles JB, Johnson PC. Cardiovascular deconditioning during space flight and the use of saline as a countermeasure to orthostatic intolerance. Aviat Space Environ Med 56: 985–990, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carll AP, Willis MS, Lust RM, Costa DL, Farraj AK. Merits of non-invasive rat models of left ventricular heart failure. Cardiovasc Toxicol 11: 91–112, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Convertino VA, Hoffler GW. Cardiovascular physiology: effects of microgravity. J Florida Med Assoc 79: 517–524, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deavers DR, Musacchia XJ, Meininger GA. Model for antiorthostatic hypokinesia: head-down tilt effects on water and salt excretion. J Appl Physiol 49: 576–582, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ek-Vitorin JF, King TJ, Heyman NS, Lampe PD, Burt JM. Selectivity of connexin 43 channels is regulated through protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation. Circ Res 98: 1498–1505, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellestad MH. Ventricular tachycardia during spaceflight. Am J Cardiol 83: 1300, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortney SM, Schneider VS, Greenleaf JE. The physiology of bed rest. In: Handbook of Physiology. Environmental Physiology, edited by Fregly MJ, Blatteis CM. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc, 1996, sect. 4, vol. II, Chapt 39, p. 889–939. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fritsch-Yelle JM, Leuenberger UA, D'Aunno DS, Rossum AC, Brown TE, Wood ML, Josephson ME, Goldberger AL. An episode of ventricular tachycardia during long-duration spaceflight. Am J Cardiol 81: 1391–1392, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grenon SM, Xiao X, Hurwitz S, Ramsdell CD, Sheynberg N, Kim C, Williams GH, Cohen RJ. Simulated microgravity induces microvolt T wave alternans. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 10: 363–370, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grippo AJ, Moffitt JA, Johnson AK. Cardiovascular alterations and autonomic imbalance in an experimental model of depression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R1333–R1341, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halliwill JR, Billman GE, Eckberg DL. Effect of a “vagomimetic” atropine dose on canine cardiac vagal tone and susceptibility to sudden cardiac death. Clin Auton Res 8: 155–164, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han J, Garciadejalon P, Moe GK. Adrenergic effects on ventricular vulnerability. Circ Res 14: 516–524, 1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hargens AR, Watenpaugh DE. Cardiovascular adaptation to spaceflight. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28: 977–982, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imanaga I. Pathological remodeling of cardiac gap junction connexin 43-With special reference to arrhythmogenesis. Pathophysiology 17: 73–81, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennings RT, Stepanek JP, Scott LR, Voronkov YI. Frequent premature ventricular contractions in an orbital spaceflight participant. Aviat Space Environ Med 81: 597–601, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanter HL, Saffitz JE, Beyer EC. Cardiac myocytes express multiple gap junction proteins. Circ Res 70: 438–444, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoo MS, Li J, Singh MV, Yang Y, Kannankeril P, Wu Y, Grueter CE, Guan X, Oddis CV, Zhang R, Mendes L, Ni G, Madu EC, Yang J, Bass M, Gomez RJ, Wadzinski BE, Olson EN, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Death, cardiac dysfunction, and arrhythmias are increased by calmodulin kinase II in calcineurin cardiomyopathy. Circulation 114: 1352–1359, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahiri MK, Kannankeril PJ, Goldberger JJ. Assessment of autonomic function in cardiovascular disease: physiological basis and prognostic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 1725–1733, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lampe PD, Cooper CD, King TJ, Burt JM. Analysis of Connexin43 phosphorylated at S325, S328 and S330 in normoxic and ischemic heart. J Cell Sci 119: 3435–3442, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lampe PD, Lau AF. The effects of connexin phosphorylation on gap junctional communication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36: 1171–1186, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lown B, Ganong WF, Levine SA. The syndrome of short P-R interval, normal QRS complex and paroxysmal rapid heart action. Circulation 5: 693–706, 1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martel E, Champeroux P, Lacolley P, Richard S, Safar M, Cuche JL. Central hypervolemia in the conscious rat: a model of cardiovascular deconditioning. J Appl Physiol 80: 1390–1396, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald KS, Delp MD, Fitts RH. Effect of hindlimb unweighting on tissue blood flow in the rat. J Appl Physiol 72: 2210–2218, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moffitt JA, Foley CM, Schadt JC, Laughlin MH, Hasser EM. Attenuated baroreflex control of sympathetic nerve activity after cardiovascular deconditioning in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 274: R1397–R1405, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moffitt JA, Grippo AJ, Beltz TG, Johnson AK. Hindlimb unloading elicits anhedonia and sympathovagal imbalance. J Appl Physiol 105: 1049–1059, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morey-Holton E, Globus RK, Kaplansky A, Durnova G. The hindlimb unloading rat model: literature overview, technique update and comparison with space flight data. Adv Space Biol Med 10: 7–40, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mueller PJ, Foley CM, Hasser EM. Hindlimb unloading alters nitric oxide and autonomic control of resting arterial pressure in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R140–R147, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagy JI, Li WE, Roy C, Doble BW, Gilchrist JS, Kardami E, Hertzberg EL. Selective monoclonal antibody recognition and cellular localization of an unphosphorylated form of connexin43. Exp Cell Res 236: 127–136, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pamnani MB, Mo Z, Chen S, Bryant HJ, White RJ, Haddy FJ. Effects of head down tilt on hemodynamics, fluid volumes, and plasma Na-K pump inhibitor in rats. Aviat Space Environ Med 67: 928–934, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Randall WC, Kroeker T, Hotmire K, Burkholder T, Huprich S, Firth K. Baroreflex responses to the stress of severe hemorrhage in the rat. Int Physiol Behav Sci 27: 197–208, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ray CA, Vasques M, Miller TA, Wilkerson MK, Delp MD. Effect of short-term microgravity and long-term hindlimb unloading on rat cardiac mass and function. J Appl Physiol 91: 1207–1213, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossum AC, Wood ML, Bishop SL, Deblock H, Charles JB. Evaluation of cardiac rhythm disturbances during extravehicular activity. Am J Cardiol 79: 1153–1155, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakowski C, Starc V, Smith SM, Schlegel TT. Sedentary long-duration head-down bed rest and ECG repolarization heterogeneity. Aviat Space Environ Med 82: 416–423, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salameh A, Krautblatter S, Karl S, Blanke K, Gomez DR, Dhein S, Pfeiffer D, Janousek J. The signal transduction cascade regulating the expression of the gap junction protein connexin43 by beta-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol 158: 198–208, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandler H. Cardiovascular effects of inactivity. In: Inactivity-physiological effects, edited by Sandler H, Vernikos-Danellis J. New York: Academic, 1986, p. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato T, Ohkusa T, Honjo H, Suzuki S, Yoshida MA, Ishiguro YS, Nakagawa H, Yamazaki M, Yano M, Kodama I, Matsuzaki M. Altered expression of connexin43 contributes to the arrhythmogenic substrate during the development of heart failure in cardiomyopathic hamster. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1164–H1173, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato T, Ohkusa T, Honjo H, Suzuki S, Yoshida MA, Ishiguro YS, Nakagawa H, Yamazaki M, Yano M, Kodama I, Matsuzaki M. Altered expression of connexin43 contributes to the arrhythmogenic substrate during the development of heart failure in cardiomyopathic hamster. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1164–H1173, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz PJ, Billman GE, Stone HL. Autonomic mechanisms in ventricular fibrillation induced by myocardial ischemia during exercise in dogs with healed myocardial infarction. An experimental preparation for sudden cardiac death. Circulation 69: 790–800, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serre PA. Citrate synthase. Methods Enzymol 13: 3–11, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh RB, Kartik C, Otsuka K, Pella D, Pella J. Brain-heart connection and the risk of heart attack. Biomed Pharmacother 56, Suppl 2: 257s–265s, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sirnes S, Kjenseth A, Leithe E, Rivedal E. Interplay between PKC and the MAP kinase pathway in Connexin43 phosphorylation and inhibition of gap junction intercellular communication. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 382: 41–45, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan MJ, Hasser EM, Moffitt JA, Bruno SB, Cunningham JT. Rats exhibit aldosterone-dependent sodium appetite during 24 h hindlimb unloading. J Physiol 557: 661–670, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takamatsu T. Arrhythmogenic substrates in myocardial infarct. Pathol Int 58: 533–543, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vaseghi M, Lux RL, Mahajan A, Shivkumar K. Sympathetic stimulation increases dispersion of repolarization in humans with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1838–H1846, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaseghi M, Shivkumar K. The role of the autonomic nervous system in sudden cardiac death. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 50: 404–419, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vasquez C, Mohandas P, Louie KL, Benamer N, Bapat AC, Morley GE. Enhanced fibroblast-myocyte interactions in response to cardiac injury. Circ Res 107: 1011–1020, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verrier RL, Antzelevitch C. Autonomic aspects of arrhythmogenesis: the enduring and the new. Curr Opin Cardiol 19: 2–11, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verrier RL, Lown B. Behavioral stress and cardiac arrhythmias. Annu Rev Physiol 46: 155–176, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker MJ, Curtis MJ, Hearse DJ, Campbell RW, Janse MJ, Yellon DM, Cobbe SM, Coker SJ, Harness JB, Harron DW. The Lambeth Conventions: guidelines for the study of arrhythmias in ischaemia infarction, and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res 22: 447–455, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodman CR, Sebastian LA, Tipton CM. Influence of simulated microgravity on cardiac output and blood flow distribution during exercise. J Appl Physiol 79: 1762–1768, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yue P, Zhang Y, Du Z, Xiao J, Pan Z, Wang N, Yu H, Ma W, Qin H, Wang WH, Lin DH, Yang B. Ischemia impairs the association between connexin 43 and M3 subtype of acetylcholine muscarinic receptor (M3-mAChR) in ventricular myocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem 17: 129–136, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao J, Su Y, Zhang Y, Pan Z, Yang L, Chen X, Liu Y, Lu Y, Du Z, Yang B. Activation of cardiac muscarinic M3 receptors induces delayed cardioprotection by preserving phosphorylated connexin43 and up-regulating cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Br J Pharmacol 159: 1217–1225, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zipes DP. Heart-brain interactions in cardiac arrhythmias: role of the autonomic nervous system. Cleve Clin J Med 75, Suppl 2: S94–S96, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]