Abstract

Mouse genetic studies reveal that ascorbic acid (AA) is essential for osteoblast (OB) differentiation and that osterix (Osx) was a key downstream target of AA action in OBs. To determine the molecular pathways for AA regulation of Osx expression, we evaluated if AA regulates Osx expression by regulating production and/or actions of local growth factors and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Inhibition of actions of IGFs by inhibitory IGFBP-4, BMPs by noggin, and ECM-mediated integrin signaling by RGD did not block AA effects on Osx expression in OBs. Furthermore, blockade of components of MAPK signaling pathway had no effect on AA-induced Osx expression. Because AA is required for prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) activity and because PHD-induced prolyl-hydroxylation targets proteins to proteosomal degradation, we next tested if AA effect on Osx expression involves activation of PHD to hydroxylate and induce ubiquitin-proteosome-mediated degradation of transcriptional repressor(s) of Osx gene. Treatment of OBs with dimethyloxallyl glycine and ethyl 3, 4-dihydroxybenzoate, known inhibitors of PHD, completely blocked AA effect on Osx expression and OB differentiation. Knockdown of PHD2 expression by Lentivirus-mediated shRNA abolished AA-induced Osx induction and alkaline phosphatase activity. Furthermore, treatment of OBs with MG115, inhibitor of proteosomal degradation, completely blocked AA effects on Osx expression. Based on these data, we conclude that AA effect on Osx expression is mediated via a novel mechanism that involves PHD2 and proteosomal degradation of a yet to be identified transcriptional repressor that is independent of BMP, IGF-I, or integrin-mediated signaling in mouse OBs.

Keywords: transcription, transcriptional repressor, bone formation, osteoblast, runx2, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

in previous studies, we and others found that mice with deletion of the gulonolactone oxidase gene (GULO), which is involved in the synthesis of an antioxidant ascorbic acid (AA), was responsible for AA deficiency and impairment of differentiated functions of osteoblast, bone fracture, and premature death in spontaneous fracture (sfx) mice (16, 32). Treatment of the mutant mice with AA in drinking water completely rescued the bone phenotypes in vivo and prevented them from premature death (32). Similarly, epidemiological studies have provided evidence for the increased risk of bone fractures caused by decreased bone formation in patients with vitamin C deficiency (26, 29, 67). In terms of mechanism for reduced bone formation during vitamin C deficiency, we have earlier reported that the impaired differentiation of bone marrow stromal (BMS) cells derived from sfx mice into osteoblasts in vitro can be rescued completely by treatment with a long acting vitamin C derivative, AA-2-phosphate (32). In subsequent studies, we found that the increase in osterix expression during in vitro differentiation of BMS cells is dependent on vitamin C (64). Furthermore, we found that AA induction of osterix mRNA expression occurred as early as 4 h after treatment, independent of new protein synthesis and mRNA stability (64). These studies strongly suggest a transcriptional regulation of osterix gene expression by AA. However, the molecular mechanism for AA regulation of osterix gene is unknown.

In terms of molecular pathways for the regulation of osteoblast differentiation, it is known that locally produced growth factors are important regulators (13, 41, 44, 45, 66). The actions of growth factors on osteoblasts are known to be mediated via activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathways (11, 17, 59). In addition, growth factors can interact with integrin signaling to regulate osteoblast functions (60). Thus, it is possible that vitamin C effects on osterix expression are mediated via vitamin C regulation of growth factor signaling pathways (59).

Vitamin C is an important cofactor for prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) proteins (28), which are members of the 2-oxoglutarate/iron-dependent dioxygenase superfamily (12). In mammals, PHD enzymes include PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 (7). Both PHD1 and PHD2 contain more than 400 amino acid residues, while PHD3 has fewer than 250. All three members, however, contain the highly conserved hydroxylase domain in the catalytic carboxy-terminal region. The importance of AA for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen to form stable triple-helical collagen both in the growing and in the mature connective tissue is well established (24, 37). The potential mechanisms by which AA directs the differentiation of multipotent progenitor cells towards bone cells are believed to be mediated through collagen matrix syntheses, cell-matrix interaction, and activation of integrin signaling (10, 14). However, the GULO knockout mice have normal levels of mature collagen production in the tail, mammary gland, and tumors (32, 36). In addition, it has been demonstrated that AA can stimulate the expression of a number of osteogenic marker genes in the presence of collagen synthesis inhibitors and can induce chondrocyte hypertrophy independent on production of a collagen-rich matrix (48). These studies indicate that additional mechanisms besides the collagen-mediated signaling may be involved in mediating AA effects on osteoblast differentiation.

Recent studies have found that PHDs are negative regulators of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α (3, 22). The hydroxylation of specific proline residues (Pro-402 and Pro-564) in the COOH-terminal oxygen-dependent degradation domains of the HIF1α by PHDs, primarily the PHD2 isoform, leads to the targeting of HIF1α for ubiquitination through an E3 ligase complex initiated by the binding of the von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL) and subsequent proteasomal degradation (3, 22). Hydroxylation of HIF1α requires molecular oxygen and iron. Under the hypoxia condition, PHDs are inhibited, and the HIF1α accumulates in the cytoplasm, which it translocates to the nucleus and binds to DNA to regulate hypoxia-responsive genes including VEGF, Runx2, and osterix (15, 55). Besides the HIF1α pathway underlying regulation of angiogenesis and osteogenesis during skeletal development, as demonstrated in other reports, PHD can hydroxylate other substrates including IKK-β, β2-adrenergic receptor, HIF1α-binding protein suppressor of cytokine signaling, and Argonaute and can influence their functions in a number of ways (6, 8, 39, 62). Because collagen prolyl hydroxylase is well known for its involvement in scurvy, in which ascorbate deficiency inhibits the enzyme resulting in defective collagen formation, we evaluated the feasibility that AA modulation of osterix gene expression is mediated via AA effects on PHD activity in osteoblasts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and biological reagents.

Antibody against β-actin was purchased from Sigma. Antibody specific to mouse osterix was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Antibody against HIF1α was a product of Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Antibody specific to PHD2 was from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). The antibody has been used and published previously (35). Dimethyloxallyl glycine (DMOG) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Peptides of MG115 (Z-Leu-Leu-Nva-H) and cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) were from Peptides International (Louisville, KY) and Bachem (Torrance, CA), respectively. Recombinant mouse noggin was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Kinase inhibitors of SB-203580, PD-98059, and SP-600125 were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Desferrioxamine (DFO), protocatechuic acid ethyl ester, aka ethyl 3, 4-dihydroxybenzoate (EDHB), and other chemicals were from Sigma. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-4 (BP-4) was purified from Escherichia coli as described previously (40). MISSION shRNA lentiviral particles against prolyl hydroxylase domain enzyme 2 (PHD2) and control nontarget were purchased from Sigma. The hairpin sequences of targeting shRNA were: mPHD2, ccggCGTCACGTTGATAACCCAAATctcgagATTTGGGTTATCAACGTGACGTTTTT; nontarget, CCGGCAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAActcgagTTGGTGCTCTTCATCTTGTTGTTTTT.

Cell culture.

Primary osteoblasts were isolated from the calvariae of 4-day to 2-wk mice by using a modified sequential digestion described previously (19, 64). Primary calvaria osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 cells were plated at 1.5× 104/cm2 (1.5 × 105/well) in 35-mm six-well culture plates in α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM) containing 10% FBS, penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The cells were cultured until 80–90% confluent prior to experiments.

Alkaline phosphatase staining and activity assay.

The cytochemical staining for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was performed according to the protocol described previously (57). Six days after AA treatment, primary calvarial osteoblasts were washed with PBS and fixed in 0.05% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 5 min. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a staining buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.6, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mg/ml naphthol AS-TR phosphate, and 0.6 mg/ml fast red violet LB diazonium (Sigma) in the dark, followed by observation without counterstain. Quantitative ALP staining areas were measured by a computer equipped with OsteoMetric system. ALP activity in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with AA or vehicle for 3 days was measured as previously reported (1).

Viral transduction.

MC3T3-E1 cells were transduced at 10 multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 24 h by adding premade viral particles stock (2.5 × 107) into the six-well culture plates in the presence of 8 μg/ml of polybrene. The cells were then infected again at 10 MOI of lentiviral particles for another 24 h to achieve maximal transduction efficiency, followed by puromycin selection (10 μg/ml) for 3–4 days. The transduced cells were trypsinized and expanded in puromycin-free growth medium prior to experiments.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

RNA was extracted from primary cultures or MC3T3-E1 cells as described previously (63, 64). An aliquot of RNA (2 μg) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA in 20 μl volume of reaction by oligo(dT)12–18 primer. Real time PCR contained 0.5 μl template cDNA, 1 × SYBR GREEN master mix (Qiagen), and 100 nM of specific forward and reverse primers in 25 μl volume of reaction. Primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time RT-PCR

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Dlx3 | 5′-CACCTACCACCACCAGTTCAA | 5′-GCTCCTCTTTCACCGACACTG |

| Dlx5 | 5′-AGAAGAGTCCCAAGCATCCGA | 5′-GCCATAAGAAGCAGAGGTAGG |

| Msx2 | 5′-CCTCGGTCAAGTCGGAAAATTC | 5′-CGTATATGGATGCTGCTTGCAG |

| Osterix | 5′-AGAGGTTCACTCGCTCTGACGA | 5′-TTGCTCAAGTGGTCGCTTCTG |

| PHD-1 | 5′-GGAACCCACATGAGGTGAAG | 5′-AACACCTTTCTGTCCCGATG |

| PHD-2 | 5′-GAAGCTGGGCAACTACAGGA | 5′-CATGTCACGCATCTTCCATC |

| PHD-3 | 5′-AAGTTACACGGAGGGGTCC | 5′-GGCTGGACTTCATGTGGATT |

| PPIA | 5′-CCATGGCAAATGCTGGACCA | 5′-TCCTGGACCCAAAACGCTCC |

| Runx2 | 5′-AAAGCCAGAGTGGACCCTTCCA | 5′-ATAGCGTGCTGCCATTCGAGGT |

| VEGF | 5′-ATATCAGGCTTTCTGGATTAAGGAC | 5′-CAGACGAAAGAAAGACAGAACAAAG |

Western blotting.

Primary osteoblasts were isolated from 2 wk old mice and cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FBS for 3 days. The cells were then lysed, and the total cellular extracts were used for immunoblotting analyses with specific antibodies to osterix, HIF1α, and β-actin as described previously (64).

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) from three to six replicates in each experiment. Data are analyzed by Student's t-test or ANOVA as appropriate. One- and two-way ANOVA tests were performed using STATISTICA software (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK).

RESULTS

AA induces osterix expression in osteoblasts.

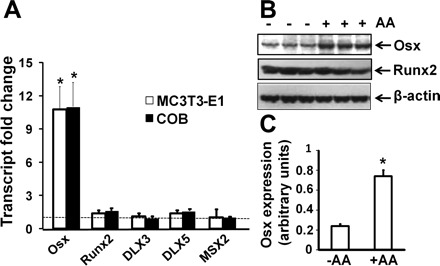

To determine if the impairment in bone formation observed in our previous studies in sfx mice is attributable to decreased expression of osteoblast-specific transcription factors, we examined the effects of AA on the expression levels of various transcription factors that are known to be involved in osteoblast differentiation. We cultured primary calvarial osteoblasts derived from 4-day to 2-wk-old mice and MC3T3-E1 cells in AA-free α-MEM supplemented with or without AA for 24 h and evaluated the expression levels of osterix, Runx2, Dlx3, Dlx5, Msx1, and Msx2 by real-time PCR (Fig. 1A). We found that 24 h AA treatment stimulated osterix expression by 10-fold in both primary calvarial osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 cells. In contrast to osterix, AA treatment did not cause significant changes in the expression levels of Runx2, Dlx3, Dlx5, and Msx2 in both primary calvarial osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 cells. Msx1 expression was below detectable level in both of these cell types (data not shown). To confirm real-time PCR data, we treated the primary osteoblasts with AA for 72 h and examined osterix protein levels by Western blot (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the mRNA data, osterix protein levels in total cell extract were increased by threefold in AA-treated primary osteoblasts compared with the cellular osterix levels from the control cells without AA treatment (Fig. 1C). In contrast, Runx2 protein levels were not increased in AA-treated cultures.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ascorbic acid (AA) on expression of various transcription factors involved in osteoblast differentiation. A: mRNA expression levels of various transcription factors. MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts and primary mouse calvarial osteoblasts (COB) were cultured in AA-free α- minimal essential medium containing 1 mg/ml BSA. The cells were treated 24 h later with 100 μg/ml AA or control vehicle for another 24 h, followed by RNA extraction for real-time RT-PCR. The results are expressed as fold changes over the expression level of controls without AA treatment. *Statistical significance compared with expression level of controls (P < 0.01, n = 3). B: protein expression levels of osterix (Osx) and Runx2 in COB, measured by Western blot. C: quantitative data of Osx expression from Western blot in B.

AA induction of osterix expression is independent of IGF-I, bone morphogenetic protein, integrin, p38, and MAP/ERK kinase pathways.

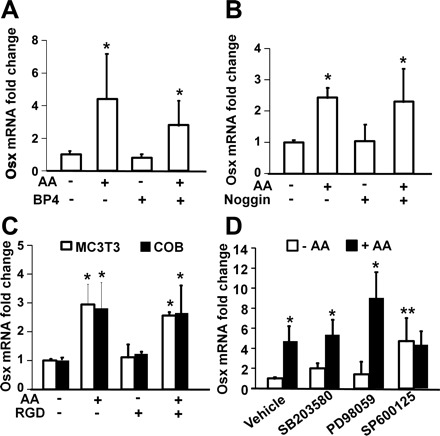

It has been known that growth factors such as bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and IGF-1 positively regulate osterix expression in osteoblasts. Therefore, it is possible that AA regulates osterix expression through modulation of local growth factor actions or there is a cross talk between AA and growth factor signaling pathways. To determine if IGF-I and/or BMP signaling is involved in regulating AA induction of osterix expression, we examined the effects of pretreatment of MC3T3 cells with inhibitory BP-4 and noggin that will bind free IGF-I and BMP, respectively, on osterix expression. MC3T3-E1 cells were pretreated with 300 ng/ml of BP-4 and 250 ng/ml of noggin, respectively, for 30 min prior to treatment with AA or without AA. RNA was extracted for real-time RT-PCR 24 h after treatment. We found that neither BP-4 nor noggin pretreatment blocked AA-induced increase in osterix expression (Fig. 2, A and B). Exogenously added BP-4 alone blocked both basal and IGF-I-induced MC3T3-E1 proliferation under the culture conditions used in this study (data not shown). Furthermore, noggin alone blocked 10 ng/ml BMP-2-induced osterix expression by 52% (P < 0.01). These positive control data suggest that BP-4 and noggin at doses used were effective in blocking IGF and BMP actions, respectively. AA is known to induce collagen expression, which activates integrin signaling. Many members of the integrin family, including α5β1, α8β1, αIIbβ3, αVβ3, αVβ5, αVβ6, and αVβ8, recognize an RGD motif within their ligands, including fibronectin, fibrinogen, vitronectin, von Willebrand factor, and many other large glycoproteins. Exogenous addition of excess RGD peptides in the culture medium can efficiently prevent these integrin-ligand interactions, thereby blocking integrin signaling. To determine if AA effect on osterix expression was mediated via activation of integrin signaling, we pretreated MC3T3-E1 cells with 5 μM RGD peptide for 30 min prior to treatment with or without AA. We observed that RGD pretreatment did not affect basal or AA-induced increase in osterix expression in MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. 2C). Consistent with these data, pretreatment with 20 nM echistatin, a known inhibitor of integrin signaling, did not block AA effects on osterix expression either (data not shown). The effectiveness of RGD peptide used to block integrin signaling was determined by evaluating the effect of these inhibitors on serum-induced MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation. RGD peptide (5 μM) blocked 1% serum-induced MC3T3-E1 proliferation by 84% (P < 0.01), thus suggesting the inhibitor was biologically active.

Fig. 2.

AA induction of Osx expression is independent of p38, MEK, JNK, IGF-I, BMP, and integrin pathways. A–C: effect of IGF-I binding protein-4 (BP-4), noggin, and cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide on AA-induced Osx mRNA expression, respectively. Primary osteoblasts or MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with vehicle, BP-4 (300 ng/ml), noggin (250 ng/ml), and RGD (5 μM), respectively, for 24 h prior to RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR. The results are expressed as fold changes compared with the expression level of vehicle control without AA treatment (n = 3). *P < 0.01 compared with expression levels of corresponding controls in the absence of AA. D: effects of inhibitors of p38, MEK, and JNK signaling pathways on AA-induced osterix expression. MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with DMSO or inhibitors of p38 (200 nM SB-203580), MEK (10 μM U-0126), and JNK (200 nM SP-600125) for 30 min prior to treatment with or without AA. RNA was extracted 24 h later for real time RT-PCR. The results are expressed as fold change compared with the expression level of DMSO control without AA treatment (n = 3). *Statistical significance compared with expression level of corresponding controls in the absence of AA (P < 0.01). **Statistical significance compared with corresponding cells treated with DMSO in the absence of AA (P < 0.05).

The effects of growth factors on osteoblast differentiation and osterix expression are known to be mediated in part via activation of MAPK signaling pathway. To identify the signaling pathways by which AA regulates osterix expression, we pretreated MC3T3-E1 cells with DMSO or effective concentrations of inhibitors of p38 (200 nM SB-203580), MAP/ERK kinase (MEK, 10 μM U-0126), and JNK (200 nM SP-600125) for 30 min prior to treatment with AA or vehicle control. We found that treatment of MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts with p38 MAPK or MEK inhibitor did not significantly influence osterix expression compared with DMSO control in the absence of AA (Fig. 2D). However, treatment of the cells with JNK inhibitor SP-600125 significantly increased osterix expression in the absence of AA. Interestingly, AA-induced increase in osterix expression was not significantly affected by p38 MAPK or MEK inhibitors. However, AA treatment failed to stimulate osterix expression in the presence of JNK inhibitor.

AA stimulates osterix expression via modulating PHD enzyme activity.

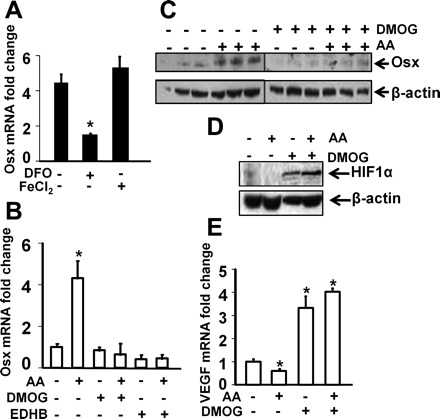

It has been known that AA is an important cofactor for PHD enzymes that catalyze posttranslational modifications of collagen and AA deficiency results in collagen maturation defects. PHDs also require Fe2+ for their enzymatic activity, and supplementation of the cells with FeCl2 increases PHD activity, while treatment of the cells with DFO, an iron chelator, inhibits PHD's ability to hydroxylate target proteins. To determine if AA effects on osterix expression are dependent on AA activation of PHD activity, we treated primary osteoblasts with DFO, FeCl2, or vehicle control in the presence or absence of AA for 24 h and examined the consequence of modulation of PHD activity by Fe2+ on AA-induced osterix expression. We found that treatment of osteoblasts with DFO resulted in a 60% reduction in AA-induced osterix expression, while treatment of the cells with FeCl2 caused a slight but insignificant increase in osterix expression (Fig. 3A). To further confirm that the AA-induced increase in osterix is mediated via a PHD-dependent mechanism, we treated primary osteoblasts with DMOG (500 μM) or EDHB (500 μM), known inhibitors of PHD, for 30 min prior to 24 h treatment with or without AA and examined the osterix mRNA and protein changes. We found that pretreatment with DMOG and EDHB completely blocked AA-induced increase in osterix expression in primary osteoblasts at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3, B and C). Similar effects were seen in primary cultures of mouse calvarial osteoblasts (data not shown). As expected, the same DMOG treatment increased HIF1α protein levels, a well-known substrate of PHDs (Fig. 3D). Hydroxylation of two conserved proline residues in HIF1α by PHDs allows recognition and binding by the pVHL, ultimately resulting in polyubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of HIF1α. Consistent with the elevated HIF1α protein, the expression of VEGF, a known HIF1α target gene, was significantly increased in the cells treated with DMOG in the presence or absence of AA, whereas the AA treatment caused a reduction in VEGF expression in the absence of DMOG (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

AA stimulates osterix expression via modulating prolyl hydroxylase activity. A: effects of desferrioxamine (DFO) and FeCl2 on AA-induced Osx expression. Primary osteoblasts were treated with DFO (50 μM), FeCl2 (0.3 μM), or vehicle control in the presence or absence of AA for 24 h. RNA was extracted for real time RT-PCR. The results were expressed as fold changes compared with the expression level of vehicle control without AA treatment (n = 3). B–E: effects of dimethyloxallyl glycineon (DMOG) or protocatechuic acid ethyl ester aka ethyl 3, 4-dihydroxybenzoate (EDHB) on AA-induced Osx, HIF1α, and VEGF expression. MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts were treated with vehicle, DMOG (500 μM), or EDHB (500 μM) for 30 min prior to 24 h treatment with or without AA. RNA and total cellular proteins were extracted for real time RT-PCR and Western blot. The results are expressed as fold change compared with the expression level of vehicle control without AA treatment (n = 3). *Statistical significance compared with expression level of corresponding controls in the absence of AA (P < 0.01).

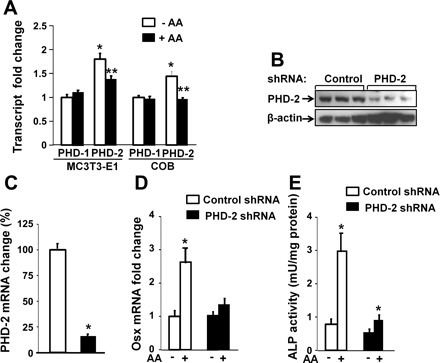

To determine which isoforms of PHDs are expressed in bone cells, we examined the transcripts of PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in primary calvarial osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 cells by real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 4A, PHD2 was expressed at higher level than PHD1, and AA treatment significantly inhibited PHD2 but not PHD1 expression. The expression of PHD3 in bone cells was undetectable (data not shown). To evaluate the role of PHD2 in regulating AA induction of osterix expression, we knocked down PHD2 expression by lentivirus-mediated shRNA and examined osterix expression in response to AA treatment in MC3T3-E1 cells. We found that PHD2 expression was reduced by nearly 80% at both protein level and transcript level in the cells infected with mouse PHD2 shRNA compared with the cells transduced with scramble control shRNA (Fig. 4, B and C). PHD1 expression was not significantly different in control shRNA vs. PHD2 shRNA-treated cells (0.94 ± 0.06-fold of control shRNA, P = 0.14). As expected, the mRNA expression of osterix was increased by 2.5-fold upon AA treatment in MC3T3-E1 cells expressing scramble control shRNA. However, AA-induced osterix induction was almost abolished in the cells expressing PHD2 shRNA (Fig. 4D). Consistent with impared expression of osterix, AA-induced ALP activity was reduced by 66% in the MC3T3 cells expressing shRNA against PHD2 compared with the cells expressing control shRNA (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of prolyl hydroxylase domain enzyme (PHD)2 expression impairs AA induction of Osx expression and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in osteoblasts. A: isoforms of PHD1 and PHD2 expression in osteoblasts. MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts and primary mouse COBs were treated with 100 μg/ml AA or control vehicle for 24 h, followed by RNA extraction for real-time RT-PCR for measurements of relative expression levels of PHD1 and PHD2. The results are expressed as fold change over the expression level of PHD1 without AA treatment. *Statistical significance compared with expression level of PHD1 without AA treatment (P < 0.01, n = 3). **Statistical significance compared with expression level of PHD2 without AA treatment (P < 0.01, n = 3). B: PHD2 expression was reduced in MC3T3 cells expressing shRNA against PHD2, measured by Western blot. C: PHD2 mRNA expression was knocked down by lentivirus-mediated shRNA. MC3T3-E1 cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing shRNA specifically against PHD2 gene or scramble DNA sequence for 24 h. Cells were lysed for RNA extraction prior to real-time RT-PCR. *Statistical significance of expression levels in the cells infected with lentivirus-shRNA against PHD2 compared with the cells infected with lentivirus-shRNA against scramble DNA sequence (P < 0.01, n = 3). D: expression levels of Osx in lentivirus-shRNA transduced cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were transduced with lentivirus-shRNA as described in B. The cells were then treated with or without AA for 24 h and lysed for real-time RT-PCR. *Statistical significance of expression level in the cells treated with AA compared with in the corresponding cells without AA treatment (P < 0.01, n = 3). E: AA-induced ALP activity was significantly reduced in the cells expressing PHD2 shRNA. *P < 0.01 in cells treated with AA vs without AA. The magnitude of ALP induction in AA-treated PHD2 shRNA cells was significantly less compared with control shRNA cells.

To further study the function of PHD2 on AA-mediated osteoblast differentiation, we treated primary calvarial osteoblasts with DMOG and vehicle control in the presence or absence of AA for 6 days. We found that treatment of AA increased ALP-stained area by more than threefold activity compared with the cells without AA treatment (Fig. 5A). However, addition of DMOG in the same AA-containing differentiation medium abolished AA-induced ALP expression as well as basal level of ALP expression (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effects of PHD enzyme inhibitor DMOG on osteoblast differentiation. A: representative images of ALP staining. Primary mouse COBs were cultured in a medium containing 10 mM β-glycerophosphate with or without 50 μg/ml of AA in the presence or absence of 500 μM DMOG for 6 days, followed by ALP activity staining. B: quantitative ALP staining area measured by the OsteoMetric system (n = 3). *Statistical significance compared with expression level of corresponding controls in the absence of AA (P < 0.01).

Ubiquitination-mediated proteosomal degradation pathway is involved in mediating AA-induced increase in osterix expression.

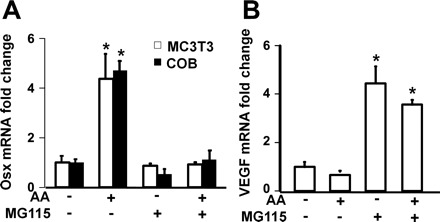

Posttranslational hydroxylation of proline residues of target proteins by PHDs lead to rapid decay via ubiquitin-proteosomal pathway. To determine if AA-induced osterix expression is mediated via a mechanism that involves prolyl hydroxylation and subsequent degradation of transcriptional suppressors or negative regulator of osterix transcription via ubiquitin-mediated pathway, we evaluated the consequence of inhibition of proteosomal degradation on osterix expression. Primary osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with MG115 (25 μM) for 30 min prior to treatment with or without AA. We found that treatment of MG115 completely blocked AA-induced increase in osterix expression in both MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts and primary mouse calvarial osteoblasts (Fig. 6A). As expected, the same treatment of MC3T3 cells with MG115 increased VEGF expression as a consequence of MG115 blockade of HIF1α degradation (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effects of MG115, proteosomal degradation inhibitor, on AA-induced Osx and VEGF expression. Primary osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts were treated with vehicle or MG115 (25 μM) for 30 min prior to treatment with or without AA. RNA was extracted for real time RT-PCR 24 h after treatment. A: expression levels of osterix in primary osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 cells, detected by real-time PCR. The results are expressed as fold change compared with the expression level of vehicle control in the same cells without AA treatment. *Statistical significance compared with expression level of control cells without AA treatment (P < 0.01, n = 3). B: expression levels of VEGF in primary osteoblasts, detected by real-time PCR. The results are expressed as fold change compared with the expression level of vehicle control in the same cells without AA treatment. *Statistical significance compared with expression level of control cells without AA treatment (P < 0.01, n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Of the various transcription factors that regulate osteoblast differentiation, Runx2 and osterix have been widely accepted as master osteogenic factors since neither Runx2 nor osterix null mice form mature osteoblasts (20, 33). While osterix is known to act downstream of Runx2 and is regulated by growth factors (27, 33, 34), little is known on other key physiological regulators of osterix expression during bone development. In our previous studies, we have found that vitamin C is an important regulator of osterix expression during osteoblast differentiation, since AA is required for increased osterix expression during osteoblast differentiation (64) and since gulonolactone oxidase-deficient mice that were unable to synthesize AA develop spontaneous fractures at a very young age as a result of defective osteoblast maturation (32). Because of the established importance of AA in the regulation of osterix expression and because osterix and AA are critical regulators of osteoblast maturation, our goal in this study was to identify the molecular pathways for AA regulation of osterix expression.

In terms of mechanism for vitamin C regulation of osterix expression, it has been shown that AA regulates production of growth factors such HGF and IGF-I (21, 58), which are known to regulate osterix expression (5, 47). Because conditional disruption of IGF-I in osteoblasts impaired osteoblast maturation and bone formation (13), we determined if AA effects on osterix expression is mediated via regulation of IGF actions. We found that blockade of IGF actions by inhibitory IGFBP-4 did not influence AA-induction of osterix expression in osteoblasts, thus suggesting that AA effect on osterix expression is not dependent on IGF action. Besides IGFs, the members of TGFβ/BMP superfamily also play critical roles in the regulation of osteoblast maturation and osterix expression (5, 27, 53). We, therefore, determined if inhibition of action of endogenously produced BMPs via exogenous addition of noggin modulated vitamin C effect on osterix expression. While noggin blocked the effect of exogenously added BMPs, it had no significant effect on AA-induced osterix expression, thus suggesting that AA effect on osterix expression is not dependent on BMP signaling pathway under the culture conditions used in this study.

Because AA has been shown to stimulate production of type I collagen in osteoblasts and because the interaction between α2-integrin and collagen has been shown to be involved in the activation of Runx2 and induction of osteoblast-specific gene expression (10, 61), we considered the possibility that AA induction of osterix expression may be mediated via activation of integrin signaling. In this study, we found that inhibition of integrin signaling via exogenous addition of echistatin did not block AA stimulation of osterix expression. Accordingly, treatment of osteoblasts with cyclic RGD peptide did not inhibit vitamin C effects on osterix expression, thus suggesting that type I collagen-mediated activation of integrin signaling is not a critical player in mediating AA effects on osterix gene transcription.

It is believed that IGF-I-mediated osterix expression requires activation of all three MAPK components (Erk1/2, p38, and JNK), whereas BMP-2 requires p38 and JNK signaling (5). Integrins are also known to activate MAPK, p38, and focal adhesion kinase to induce expression of osteoblast-specific transcription factors (43, 60, 61). Consistent with the results from inhibition of IGF-I, BMP, and integrin signaling, we found that pretreatment of MC3T3-E1 cells with effective concentrations of p38 MAPK and ERK1/2-specific inhibitors had no effect on AA-induced osterix expression. In contrast, BMP-2-induced osterix expression was completely blocked by p38 MAPK and JNK inhibitors (data not shown). Thus, our findings argue against a key role of endogenously produced IGF-I, BMP, and type I collagen in mediating vitamin C effects on osterix expression under culture conditions used in this study.

Vitamin C is an important cofactor of collagen prolyl hydroxylase, and several distinct prolyl hydroxylases are known to hydroxylate HIF transcription factors. In present study, we examined the effect of two well-studied chemical inhibitors of PHDs, DMOG and EHDB, on osterix expression. Both inhibitors completely abolished AA-induction of osterix expression in MC3T3-E1 cells as well as in primary osteoblasts. Besides vitamin C, iron and oxoglutarate are important cofactors for PHD activity. Accordingly, we found that treatment of MC3T3-E1 cells with DFO, which binds to iron, also inhibited AA induction of osterix expression. These findings provide first evidence that vitamin C effect on osterix expression is mediated via PHD-dependent mechanism.

Three isoforms of PHDs are widely distributed among different organs at the transcript level. PHD1 is expressed at the highest level in testes, whereas PHD3 is the highest in the heart (25). At protein level, however, PHD2 is the most abundant in all mouse organs examined (50). Consistent with previous studies, we found that PHD2 was predominantly expressed in osteoblasts, and its expression was slightly reduced in response to AA treatment presumably because of a negative feedback, which is similar to downregulation of receptor expression by treatment with its ligands (18, 42). PHD3 was not expressed in osteoblasts. Knock-down of 80% PHD2 expression by lentivirus-mediated shRNA abolished AA-induced osterix induction in osteoblasts. Interestingly, PHD2 has been reported to be a major regulator of transcription factor HIF1α (2), and knockout of PHD2 causes embryonic lethality during organogenesis with abnormal placental and cardiac morphology (52), while conditional knockout of PHD2 in somatic cells displayed reduced body size, increased angiogenesis, and premature death (31). Mice with conditional deletion of PHD2 in chondrocytes were born normal but quickly became growth-retarded because of increased cartilage matrix mineralization (23). In contrast, knockout of PHD1 in mice exhibited no apparent abnormalities in cardiovascular, hematopoietic, or placental morphology and skeleton (51, 52). PHD1/PHD3 double deficiency led to hepatic accumulation of HIF2α, but not HIF1α (50). Our data together with the phenotypes of specific PHD gene knockout data strongly indicate that PHD2 may play an important role in mediating AA effects on osterix expression and osteoblast differentiation, and PHD1, although expressed, cannot compensate for the loss of PHD2 in mediating osterix induction in osteoblasts.

PHD enzymes catalyze hydroxylation of the specific proline and asparagine residues of their substrates such as HIFα (9). Prolyl-4 hydroxylation at two sites within a central degadation domain of HIF1α by PHDs, mainly PHD2, mediates interactions with the VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that targets HIF1α for proteasomal degradation (4, 7). Hydroxylation of an asparaginyl residue in the COOH-terminal activation domain by PHDs inhibits transcriptional activity by preventing interaction with co-activator, p300/CBP (30). The HIF hydroxylases are dependent on ascorbate, and activation of PHDs in AA-treated cells allows HIF1α to undergo proteolysis and becomes transcriptionally inactive, therefore inhibiting its target gene expression. Accordingly, we found that inhibition of PHDs by DMOG increased HIF1α protein levels in osteoblasts. Furthermore, treatment of osteoblasts with DMOG increased HIF1α target gene, VEGF expression. In recent studies, it has been shown that HIF1α is a transcriptional activator of osterix gene transcription via hypoxia response element present in osterix gene promoter (55). If the vitamin C effect on osterix is mediated via HIF1α-dependent mechanism, we would then anticipate increased osterix expression in cultures treated with PHD inhibitors. However, we found that treatment of osteoblasts with DMOG and EDHB increased HIF1α level but decreased osterix expression and osteoblast differentiation. Furthermore, conditional disruption of HIF1α in cells of osteoblastic lineage impaired skeletal development (38, 54). In this regard, mice with conditional disruption of HIF1α in the condensing mesenchyme had shortened bones, less-mineralized skulls, and widened sutures due to massive apoptosis and altered proliferation of chondrocytes in growth plate (38). Because previous studies have demonstrated that HIF1α is a positive regulator of bone formation, it is unlikely that HIF1α is a repressor that mediates vitamin C effects on osterix expression.

Because prolyl hydroxylation of target proteins by PHDs leads to ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation and because pretreatment of MC3T3-E1 cells with inhibitors of proteosomal degradation blocked AA-induced osterix expression, we speculate that AA-mediated activation of PHDs leads to prolyl hydroxylation and subsequent degradation of one or more negative regulators of osterix transcription. We ruled out Runx2 as a potential candidate although it is upstream of osterix and indispensable for osterix expression for two reasons: First, Runx2 is a positive regulator of osterix expression. Second, AA treatment did not increase protein levels of Runx2. In recent studies, tumor suppressor gene, p53, has been identified as a negative regulator of osterix expression (56). It was found that p53 knockout mice exhibited increased bone formation and osteoblast differentiation that could be explained by increased osterix expression. Furthermore, osterix could be repressed by p53 in reporter assays. Stat1 and E4BP4 have also been identified as negative regulators of osterix expression (46, 49). PHDs also regulate the stability of IKK, therefore affecting NF-κB pathway (65). We recently published that NFE2L1 could in part mediate AA effects on osterix expression in vitro and in vivo. Future studies will address whether NFE2L1, NF-κB, p53, and/or other suppressors of osterix expression are direct or indirect targets of PHD2 to mediate AA action in osteoblasts.

In summary, we have provided first experimental data for involvement of PHD-dependent mechanism for mediating the effects of vitamin C on osterix expression and osteoblast differentiation. Future identification of the PHD target transcriptional suppressor/s could lead to development of therapies to increase osteoblast differentiation and promote bone formation to treat metabolic bone disorders.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a merit review grant from the VA.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All work was performed in facilities provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The authors thank Catrina Alarcon for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaar YG, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Ras-Association Domain Family 1 Protein, RASSF1C, Is an IGFBP-5 Binding Partner and a Potential Regulator of Osteoblast Cell Proliferation. J Bone Miner Res 20: 1430–1439, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelhoff RJ, Tian YM, Raval RR, Turley H, Harris AL, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Gleadle JM. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem 279: 38458–38465, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berra E, Ginouves A, Pouyssegur J. The hypoxia-inducible-factor hydroxylases bring fresh air into hypoxia signalling. EMBO Rep 7: 41–45, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science 294: 1337–1340, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celil AB, Campbell PG. BMP-2 and insulin-like growth factor-I mediate Osterix (Osx) expression in human mesenchymal stem cells via the MAPK and protein kinase D signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 280: 31353–31359, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummins EP, Berra E, Comerford KM, Ginouves A, Fitzgerald KT, Seeballuck F, Godson C, Nielsen JE, Moynagh P, Pouyssegur J, Taylor CT. Prolyl hydroxylase-1 negatively regulates IkappaB kinase-beta, giving insight into hypoxia-induced NFkappaB activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 18154–18159, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O'Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJC. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107: 43–54, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson JE, 3rd, Wu Y, Smith K, Charles P, Powers K, Wang H, Patterson C. ASB4 is a hydroxylation substrate of FIH and promotes vascular differentiation via an oxygen-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol 27: 6407–6419, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong GH, Takeda K. Role and regulation of prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Cell Death Differ 15: 635–641, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franceschi RT, Iyer BS, Cui Y. Effects of ascorbic acid on collagen matrix formation and osteoblast differentiation in murine MC3T3–E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 9: 843–854, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge C, Xiao G, Jiang D, Franceschi RT. Critical role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-MAPK pathway in osteoblast differentiation and skeletal development. J Cell Biol 176: 709–718, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould BS. Ascorbic acid and collagen fiber formation. Vitam Horm 18: 89–120, 1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govoni KE, Wergedal JE, Florin L, Angel P, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Conditional deletion of IGF-I in collagen type 1alpha2 (Col1alpha2) expressing cells results in postnatal lethality and a dramatic reduction in bone accretion. Endocrinology 148: 5706–5715, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green J, Schotland S, Stauber DJ, Kleeman CR, Clemens TL. Cell-matrix interaction in bone: type I collagen modulates signal transduction in osteoblast-like cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C1090–C1103, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang LE, Bunn HF. Hypoxia-inducible factor and its biomedical relevance. J Biol Chem 278: 19575–19578, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiao Y, Li X, Beamer WG, Yan J, Tong Y, Goldowitz D, Roe B, Gu W. A deletion causing spontaneous fracture identified from a candidate region of mouse Chromosome 14. Mamm Genome 16: 20–31, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz M, Amit I, Yarden Y. Regulation of MAPKs by growth factors and receptor tyrosine kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773: 1161–1176, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawane T, Mimura J, Yanagawa T, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Horiuchi N. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) down-regulates PTH/PTH-related protein receptor gene expression in UMR-106 osteoblast-like cells via a 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent, protein kinase A-independent pathway. J Endocrinol 178: 247–256, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Xing W, Wergedal JE, Chan JY, Mohan S. Targeted disruption of nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 1 in osteoblasts reduces bone size and bone formation in mice. Physiol Genomics 40: 100–110, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamoto R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell 89: 755–764, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwack MH, Shin SH, Kim SR, Im SU, Han IS, Kim MK, Kim JC, Sung YK. l-Ascorbic acid 2-phosphate promotes elongation of hair shafts via the secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 from dermal papilla cells through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Br J Dermatol 160: 1157–1162, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lando D, Peet DJ, Whelan DA, Gorman JJ, Whitelaw ML. Asparagine hydroxylation of the HIF transactivation domain a hypoxic switch. Science 295: 858–861, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laperre K, Fraisl P, Van Looveren R, Bouillon R, Carmeliet P, Carmeliet G. Deletion of the oxygen-sensor PHD2 in chondrocytes results in increased cartilage and bone mineralization. J Bone Miner Res: S44, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leboy PS, Vaias L, Uschmann B, Golub E, Adams SL, Pacifici M. Ascorbic acid induces alkaline phosphatase, type X collagen, and calcium deposition in cultured chick chondrocytes. J Biol Chem 264: 17281–17286, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieb ME, Menzies K, Moschella MC, Ni R, Taubman MB. Mammalian EGLN genes have distinct patterns of mRNA expression and regulation. Biochem Cell Biol 80: 421–426, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maggio D, Barabani M, Pierandrei M, Polidori MC, Catani M, Mecocci P, Senin U, Pacifici R, Cherubini A. Marked decrease in plasma antioxidants in aged osteoporotic women: results of a cross-sectional study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 1523–1527, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsubara T, Kida K, Yamaguchi A, Hata K, Ichida F, Meguro H, Aburatani H, Nishimura R, Yoneda T. BMP2 regulates Osterix through Msx2 and Runx2 during osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem 283: 29119–29125, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonough MA, Li V, Flashman E, Chowdhury R, Mohr C, Lienard BM, Zondlo J, Oldham NJ, Clifton IJ, Lewis J, McNeill LA, Kurzeja RJ, Hewitson KS, Yang E, Jordan S, Syed RS, Schofield CJ. Cellular oxygen sensing: Crystal structure of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase (PHD2). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 9814–9819, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melhus H, Michaelsson K, Holmberg L, Wolk A, Ljunghall S. Smoking, antioxidant vitamins, and the risk of hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res 14: 129–135, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metzen E, Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Stengel P, Marxsen JH, Stolze I, Klinger M, Huang WQ, Wotzlaw C, Hellwig-Burgel T, Jelkmann W, Acker H, Fandrey J. Intracellular localisation of human HIF-1 alpha hydroxylases: implications for oxygen sensing. J Cell Sci 116: 1319–1326, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Bardeesy N, Cullen D, Bronson RT, Kaelin WG., Jr Somatic inactivation of the PHD2 prolyl hydroxylase causes polycythemia and congestive heart failure. Blood 111: 3236–3244, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohan S, Kapoor A, Singgih A, Zhang Z, Taylor T, Yu H, Chadwick RB, Chung YS, Donahue LR, Rosen C, Crawford GC, Wergedal J, Baylink DJ. Spontaneous fractures in the mouse mutant sfx are caused by deletion of the gulonolactone oxidase gene, causing vitamin C deficiency. J Bone Miner Res 20: 1597–1610, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 108: 17–29, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishio Y, Dong Y, Paris M, O'Keefe RJ, Schwarz EM, Drissi H. Runx2-mediated regulation of the zinc finger Osterix/Sp7 gene. Gene 372: 62–70, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park KS, Whitsett JA, Di Palma T, Hong JH, Yaffe MB, Zannini M. TAZ interacts with TTF-1 and regulates expression of surfactant protein-C. J Biol Chem 279: 17384–17390, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsons KK, Maeda N, Yamauchi M, Banes AJ, Koller BH. Ascorbic acid-independent synthesis of collagen in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E1131–E1139, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterkofsky B. Ascorbate requirement for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen: relationship to inhibition of collagen synthesis in scurvy. Am J Clin Nutr 54: 1135S–1140S, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provot S, Zinyk D, Gunes Y, Kathri R, Le Q, Kronenberg HM, Johnson RS, Longaker MT, Giaccia AJ, Schipani E. Hif-1alpha regulates differentiation of limb bud mesenchyme and joint development. J Cell Biol 177: 451–464, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qi HH, Ongusaha PP, Myllyharju J, Cheng D, Pakkanen O, Shi Y, Lee SW, Peng J. Prolyl 4-hydroxylation regulates Argonaute 2 stability. Nature 455: 421–424, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin X, Strong DD, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Structure-function analysis of the human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-4. J Biol Chem 273: 23509–23516, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development 133: 3231–3244, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenthal SM, Brunetti A, Brown EJ, Mamula PW, Goldfine ID. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I receptor expression during muscle cell differentiation. Potential autocrine role of IGF-II. J Clin Invest 87: 1212–1219, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salasznyk RM, Klees RF, Williams WA, Boskey A, Plopper GE. Focal adhesion kinase signaling pathways regulate the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Cell Res 313: 22–37, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasaki T, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr, Chou S, Urata MM, Slavkin H, Chai Y. TGFbeta-mediated FGF signaling is crucial for regulating cranial neural crest cell proliferation during frontal bone development. Development 133: 371–381, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulz C, Kress W, Schomig A, Wessely R. Endocardial cushion defect in a patient with Crouzon syndrome carrying a mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-2 gene. Clin Genet 72: 305–307, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silvestris F, Cafforio P, De Matteo M, Calvani N, Frassanito MA, Dammacco F. Negative regulation of the osteoblast function in multiple myeloma through the repressor gene E4BP4 activated by malignant plasma cells. Clin Cancer Res 14: 6081–6091, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Standal T, Abildgaard N, Fagerli UM, Stordal B, Hjertner O, Borset M, Sundan A. HGF inhibits BMP-induced osteoblastogenesis: possible implications for the bone disease of multiple myeloma. Blood 109: 3024–3030, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan TA, Uschmann B, Hough R, Leboy PS. Ascorbate modulation of chondrocyte gene expression is independent of its role in collagen secretion. J Biol Chem 269: 22500–22506, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tajima K, Takaishi H, Takito J, Tohmonda T, Yoda M, Ota N, Kosaki N, Matsumoto M, Ikegami H, Nakamura T, Kimura T, Okada Y, Horiuchi K, Chiba K, Toyama Y. Inhibition of STAT1 accelerates bone fracture healing. J Orthop Res 28: 937–941, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeda K, Aguila HL, Parikh NS, Li X, Lamothe K, Duan LJ, Takeda H, Lee FS, Fong GH. Regulation of adult erythropoiesis by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Blood 111: 3229–3235, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeda K, Cowan A, Fong GH. Essential role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis of the adult vascular system. Circulation 116: 774–781, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takeda K, Ho VC, Takeda H, Duan LJ, Nagy A, Fong GH. Placental but not heart defects are associated with elevated hypoxia-inducible factor alpha levels in mice lacking prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2. Mol Cell Biol 26: 8336–8346, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ulsamer A, Ortuno MJ, Ruiz S, Susperregui AR, Osses N, Rosa JL, Ventura F. BMP-2 induces Osterix expression through up-regulation of Dlx5 and its phosphorylation by p38. J Biol Chem 283: 3816–3826, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wan C, Gilbert SR, Wang Y, Cao X, Shen X, Ramaswamy G, Jacobsen KA, Alaql ZS, Eberhardt AW, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA, Deng L, Clemens TL. Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha pathway accelerates bone regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 686–691, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wan C, Shao J, Gilbert SR, Riddle RC, Long F, Johnson RS, Schipani E, Clemens TL. Role of HIF-1alpha in skeletal development. Ann NY Acad Sci 1192: 322–326, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X, Kua HY, Hu Y, Guo K, Zeng Q, Wu Q, Ng HH, Karsenty G, de Crombrugghe B, Yeh J, Li B. p53 functions as a negative regulator of osteoblastogenesis, osteoblast-dependent osteoclastogenesis, and bone remodeling. J Cell Biol 172: 115–125, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wergedal JE, Baylink DJ. Characterization of cells isolated and cultured from human bone. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 176: 60–69, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu YL, Gohda E, Iwao M, Matsunaga T, Nagao T, Takebe T, Yamamoto I. Stimulation of hepatocyte growth factor production by ascorbic acid and its stable 2-glucoside. Growth Horm IGF Res 8: 421–428, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiao G, Cui Y, Ducy P, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT. Ascorbic acid-dependent activation of the osteocalcin promoter in MC3T3–E1 preosteoblasts: requirement for collagen matrix synthesis and the presence of an intact OSE2 sequence. Mol Endocrinol 11: 1103–1113, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiao G, Gopalakrishnan R, Jiang D, Reith E, Benson MD, Franceschi RT. Bone morphogenetic proteins, extracellular matrix, and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways are required for osteoblast-specific gene expression and differentiation in MC3T3–E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 17: 101–110, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao G, Wang D, Benson MD, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT. Role of the alpha2-integrin in osteoblast-specific gene expression and activation of the Osf2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem 273: 32988–32994, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie L, Xiao K, Whalen EJ, Forrester MT, Freeman RS, Fong G, Gygi SP, Lefkowitz RJ, Stamler JS. Oxygen-regulated beta(2)-adrenergic receptor hydroxylation by EGLN3 and ubiquitylation by pVHL. Sci Signal 2: ra33, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xing W, Baylink D, Kesavan C, Hu Y, Kapoor S, Chadwick RB, Mohan S. Global gene expression analysis in the bones reveals involvement of several novel genes and pathways in mediating an anabolic response of mechanical loading in mice. J Cell Biochem 96: 1049–1060, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xing W, Singgih A, Kapoor A, Alarcon CM, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Nuclear factor-E2-related factor-1 mediates ascorbic acid induction of osterix expression via interaction with antioxidant-responsive element in bone cells. J Biol Chem 282: 22052–22061, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xue J, Li X, Jiao S, Wei Y, Wu G, Fang J. Prolyl hydroxylase-3 is down-regulated in colorectal cancer cells and inhibits IKKbeta independent of hydroxylase activity. Gastroenterology 138: 606–615, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu K, Xu J, Liu Z, Sosic D, Shao J, Olson EN, Towler DA, Ornitz DM. Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development 130: 3063–3074, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang J, Munger RG, West NA, Cutler DR, Wengreen HJ, Corcoran CD. Antioxidant intake and risk of osteoporotic hip fracture in Utah: an effect modified by smoking status. Am J Epidemiol 163: 9–17, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]