Abstract

Autophagy, a cellular housekeeping process, is essential to maintain tissue homeostasis, particularly in long-lived cells such as cardiomyocytes. Autophagic activity declines with age and may explain many features of age-related cardiac dysfunction. In this review we summarize the current state of knowledge regarding age-related changes in autophagy in the heart. Recent findings from studies in human hearts are presented, including evidence that the autophagic response is intact in the aged human heart. Impaired autophagic clearance of protein aggregates or deteriorating mitochondria will have multiple consequences including increased arrhythmia risk, decreased contractile function, reduced tolerance to ischemic stress, and increased inflammation; thus autophagy represents a potentially important therapeutic target to mitigate the cardiac consequences of aging.

Keywords: autophagy, cardiac, aging, inflammation, human studies

Autophagy Machinery

Autophagy is the process that maintains cellular homeostasis through the renewal/recycling of cytoplasmic materials, organelles (such as mitochondria), removal of aggregated proteins, and the provision of energy and biomolecules to cells [1]. Autophagy has been demonstrated to play an important role in an array of age-related diseases, contributing to diseases such as neurodegenerative and muscle disorders, cancer, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, as well as infection and inflammation [2–11] and many, many others.

Autophagy is characterized by the delivery of intracellular components to the lysosome, which can be accomplished via three different mechanisms that are thought to operate simultaneously in most cell types [12]: microautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy, and macroautophagy. Microautophagy is a constitutive process by which random invaginations in the lysosomal or vacuolar (plants) membrane deliver cytoplasm to the lysosomal lumen via single membrane vesicles, resulting in the degradation of cytoplasmic material [13–15]. The microautophagy pathway is important during nutrient starvation [15] targeting glycogen to the lysosome [16], and selective degradation of peroxisomes, mitochondria, and parts of the nucleus (yeast) [13]. Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is characterized by lysosomal targeting, translocation across the lysosomal membrane, and subsequent degradation of specific, predominantly cytosolic proteins containing a pentapeptide motif biochemically related to KFERQ [17]. A process solely identified in mammals, CMA does not require the formation of a membrane; instead, a cytosol-borne heat shock cognate protein of 70 kDa, Hsp70, binds the target, and ferries it to a complex consisting of LAMP2A (Lysosome-Associated Membrane Protein 2A) and Hsp90 embedded in the lysosomal membrane, promoting protein unfolding [18]. The LAMP2A complex multimerizes and threads the protein into the lysosomal lumen where the protein is destroyed. CMA is thought to be constitutive in most cell types in order to maintain homeostasis by clearing non-functional proteins. It has been shown to respond to starvation (although its response is somewhat delayed compared to macroautophagy [19]) and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [20] and has been shown to decline with age [21–23]. Finally, macroautophagy is a form of autophagy that relies on the de novo formation of a double membrane vesicle (autophagosome) around the cargo to be degraded. This constitutive process has been shown to greatly increase in times of stress, e.g. starvation [24], myocardial ischemia [25], and infection [9]. Of the three autophagy pathways, macroautophagy is the best characterized and is discussed in greater detail below.

The macroautophagy pathway consists of 36 identified proteins of which 16 are considered essential elements of the core machinery [26]. There are a variety of excellent reviews of the autophagy pathway and its regulation [1, 27, 28]. The initiation of autophagy is accomplished through the inactivation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [27, 29]. mTOR maintains ULK1 (human homolog of Atg1 in yeast) in the phosphorylated form (pULK1-Ser-757) that prevents it from initiating autophagy [27]. Autophagy-inducing stimuli release mTOR repression of ULK1, allowing it to activate the Beclin-1 complex [30]. The Beclin-1 complex in addition to other autophagy proteins assist in phagophore nucleation and the recruitment of proteins associated with phagophore elongation [30, 31]. The origin of the membrane is still being elucidated, however, it appears that the ER (the primary site of autophagosome assembly) [32–34], the mitochondrial membrane [35], and the plasma membrane [36] are the likely sources.

Elongation of the phagophore requires ubiquitin-like conjugation systems that help to convert LC3 into the LC3-II form that is incorporated in the autophagosomal membrane. One system utilizes Atg7 and Atg10 to create the irreversible covalent linkage between Atg5-Atg12, which then associates with Atg16L1 to form a complex required for membrane elongation [27]. A second ubiquitin-like conjugating system is required for the incorporation of LC3-II into the autophagosomal double membrane [27]. Atg4 cleaves the terminal amino acid(s) from LC3, yielding LC3-I. The activities of the ubiquitin-like proteins Atg3 and Atg7 in conjunction with or without the Atg5-12-16L1 complex facilitate the addition of phosphatidylethanolamine to LC3-I, resulting in LC3-II and subsequent incorporation of LC3-II into the autophagosomal membrane [27, 37]. LC3-II is incorporated into both faces (convex and concave) of the cup-shaped phagophore double-membrane structure [27]. Upon formation of the autophagosome, Atg5-Atg12-Atg16L1 dissociates from the autophagosomal double-membrane and LC3-II is recycled from the outer leaflet and converted to LC3-I again by Atg4 (LC3-II incorporated into the inner leaflet is eventually degraded by lysosomal hydrolases following autophagosome-lysosome fusion) [27]. The autophagosomes can fuse with other autophagosomes, with endosomes (amphisome), or with lysosomes (autolysosome or autophagolysosome) [38].

LAMP2 isoforms expressed on the lysosomal surface mediate fusion with the autophagosome resulting in formation of the autophagolysosome. Lytic lysosomal enzymes catalyze the degradation of the inner autophagosomal membrane along with its protein/organelle cargo [27]. In order to target specific substrates for degradation, the autophagy system relies on a handful of adapter proteins of which p62/SQSTM-1 is the best characterized in the context of targeting protein aggregates to the autophagy pathway [39]. P62 possesses domains for binding both LC3 and ubiquitin, meaning that it binds ubiquitinated substrates and targets them to the autophagy pathway via its LC3 binding domains [40]. Therefore, if the autophagic pathway is functioning normally, levels of p62 and ubiquitin-tagged proteins should not increase. Since the role of p62 in autophagy is aggregate association, studies of p62 require differential analysis of detergent-soluble and detergent-insoluble protein fractions [39]. P62 also serves as an important adaptor protein for mitochondria whose outer membrane is tagged with ubiquitin [41] by Parkin [42] or other ubiquitin ligases such as MULAN [43].

Role of Autophagy in Longevity in Animal Models

Autophagy serves a cytoprotective function through the removal of toxic protein aggregates, damaged mitochondria and harmful reactive oxygen species, intracellular infectious pathogens, etc. Autophagy not only contributes to cell survival but is involved in organismal lifespan. The association between autophagy and lifespan extension was first noted by brain-specific overexpression of Atg8a in D. melanogaster [44] and later, by general overexpression of Atg5 in mice [45]. These proteins are essential for autophagosome formation and overexpression was found to not only extend median lifespan but also promote anti-aging phenotypes, including leanness, increased insulin sensitivity, and improved motor function. Although several manipulations may lead to life extension, a common denominator is their association to autophagy [46]. Importantly, these interventions have been shown to extend to many animal species. Several conserved genes that have been shown to increase lifespan, e.g., sirtuin 1, also induce autophagy. Rapamycin, a pharmacological inducer of autophagy, inhibits TORC1 (target of rapamycin complex 1) and prolongs lifespan in several organisms, as does caloric restriction [47–49].

Both sirtuin1 and rapamycin promote lifespan under conditions in which autophagy is induced [50–52]. Sirtuin 1 is a conserved NAD+ dependent histone deacetylase that affects major regulators of autophagy (e.g., AMP-dependent kinase [AMPK]) and autophagy-related gene products (e.g., Atg5, Atg7, Atg8) [53]. It was shown that deletion of Beclin-1 (Atg6) not only suppressed the induction of autophagy by sirtuin 1 expression but it also abrogated the effect of sirtuin 1 in extending lifespan [50]. Lifespan extension by rapamycin was inhibited through deletion or silencing of Atg1, Atg7 or Atg5 [51, 52]. It should be noted that although many findings, such as these, support a linkage between autophagy and lifespan, many of the essential regulators of autophagy that have been shown to demonstrate this relationship (e.g., Beclin-1) may also function in other homeostatic cellular pathways. Thus, longevity may not be solely dependent on autophagy.

Autophagy in the Heart in Animal Models of Aging

One of the preeminent damaged-based theories of aging that is applicable to the heart involves cellular damage associated with cumulative damage from ROS [54, 55]. The high metabolic activity of the heart is supported by a large population of mitochondria and a steady supply of oxygen. Moreover, cardiomyocytes are replaced infrequently [56], making them ideal candidates for oxidative damage and stress with the passage of time [57, 58]. Dysfunctional mitochondria are a known source of ROS, which has led some researchers to suggest that the age-related accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria (and the ROS they generate) is due to a reduction in autophagy (specifically mitophagy) [57, 59]. As a result, dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate as the cells age, presumably due to the loss of mitophagy, and promote the formation of ROS, which negatively modifies DNA, proteins, membranes, and organelles, leading to further accumulation of damaged mitochondria and ROS creating a positive feedback loop that results in the “aging” phenotype with a decline in mitophagy/autophagy at its core [55, 57, 60, 61]. There are several lines of evidence that suggest that this is possible.

First, it is well established that as the heart ages, basal ROS levels increase [58] and a large number of mitochondria from aged post-mitotic cells are enlarged and typically suffer from a loss of function and turnover mechanisms, i.e. fission, fusion, protein quality control, and removal by autophagy (reviewed in Terman et al. [62]). Second, autophagy, and by extension mitophagy, has been shown to be a vital component of cellular homeostasis by degrading dysfunctional mitochondria, thus limiting ROS production and making the study of autophagy relevant to many cardiovascular diseases, e.g. ischemia/reperfusion injury [63]. Third, ROS have been shown to induce autophagy in vitro via AMPK activation [64] and/or by regulating Atg4 activity in vitro [65], establishing that the cellular response to ROS involves autophagy, likely as a mechanism to limit further ROS production from damaged mitochondria and potentially as a means to eliminate oxidatively damaged organelles and protein aggregates. Fourth, a cardiac-specific deletion of the autophagy protein, Atg5, resulted in an age-related accumulation of abnormal or “collapsed mitochondria,” a decline in respiratory function, and a decrease in mitochondrial removal, indicating that autophagy is vital to preserve cardiac function in the aged [66]. Finally, interactions between ROS and iron-containing macromolecules have been shown to promote the formation and accumulation of an intralysosomal aggregate, lipofuscin, as cells age (a well described hallmark of aging) [61, 62, 67, 68]. Lipofuscin is indigestible, contributes to dysregulation of lysosomal pH, and possibly prevents/limits autophagy by disrupting lysosome/autophagosome fusions. Taken together, these studies demonstrate a link between autophagy, ROS, and aging with an age-related dysregulation of autophagy at its core.

It is generally accepted that autophagy declines with age, based on indirect evidence provided by the lipofuscin and ROS studies in the aged heart [62, 66, 67, 69–75]. However, to get a clear indication of how autophagy is manifest in the aging heart, the autophagy pathway must be interrogated directly. Autophagy is commonly measured by western blotting for LC-II [76], in which it is generally accepted that an increase in LC3-II is associated with an increase in autophagy (although increased LC3-II could also result from impaired autophagic flux). Studies of autophagy in the aging heart have yielded inconsistent results. For example, Inuzuka et al. demonstrated that LC3-II remains constant when comparing 3 to 20–24 month old FVB mice [74]. Additionally, Taneike et al. showed that LC3-II levels decline when comparing 2.5 mo and 26 mo C57BL/6 mice [66]. Conversely, Boyle and colleagues showed an increase in LC3-II and Beclin-1 levels when comparing 2 mo and 18 mo C57BL/6 mice [72]. Finally, Wohlgemuth et al. [71] compared 6 mo and 26 mo Fisher 344 rat hearts and showed an age-related increase in Beclin-1, LC3-I, LC3-II, no change in Atg7, and a decline in Atg9. The inconsistencies in the data could be due to differences in mouse strain or species, ages of the animals being compared, conditions under which the animals were maintained, or even time of day at which tissues were harvested. As reviewed elsewhere [Gottlieb CircRes, manuscript in second revision], measurement of autophagic flux would be more informative than “snapshot” LC3-II levels. In our unpublished studies of C57BL/6 mice, autophagic flux is impaired in aged mice (24mo vs 3mo). Consequently, more work needs to be done to characterize how autophagy in the heart changes with age and how those specific changes are manifest.

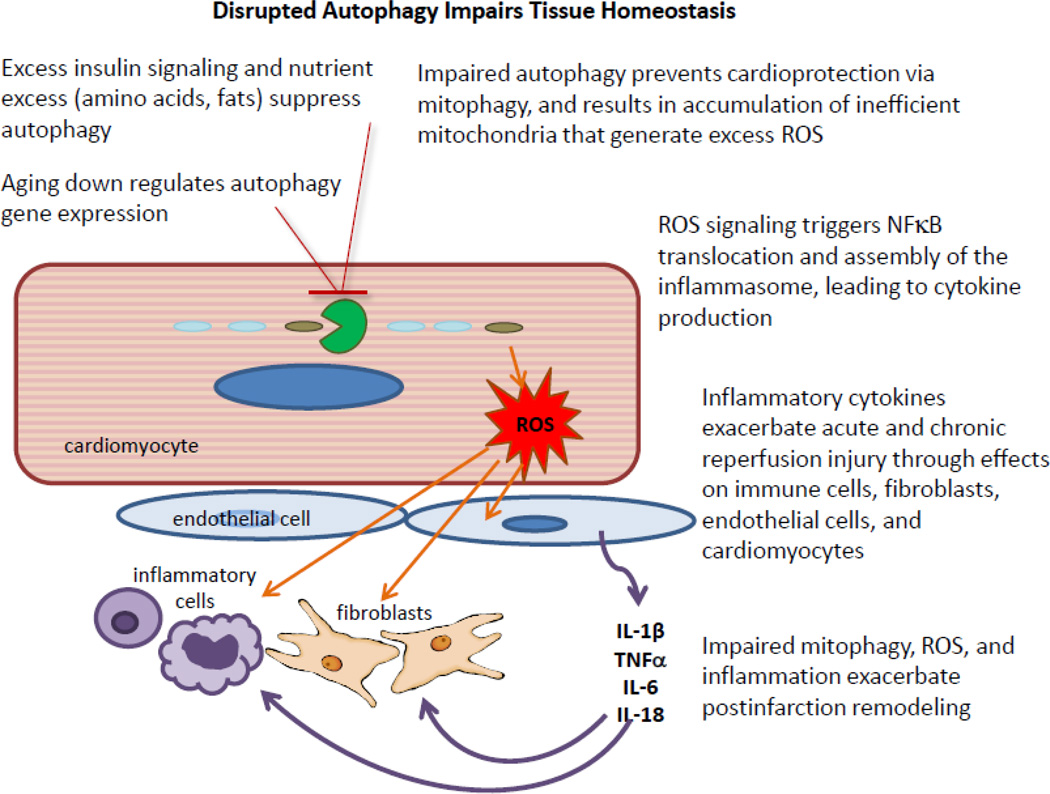

Autophagic clearance of mitochondria is important for maintenance of mitochondrial function, limitation of ROS production, and as a prerequisite for mitochondrial biogenesis. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis is recognized as an early event in heart failure [77], and is a feature of cardiac aging [78]. Overexpression of parkin, a ubiquitin ligase important for mitochondrial turnover, ameliorated the age-related decline in cardiac function [78], whereas parkin deficiency results in accumulation of abnormal mitochondria, particularly after injury [79]. Preservation of mitochondrial integrity is important not only for ATP production and calcium homeostasis necessary for contractile function and stable electrical conduction, but also to limit ROS production and inflammation. Thus impaired mitochondrial clearance through autophagy will have multiple consequences including increased arrhythmia risk, decreased contractile reserve, and reduced tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion injury, and increased inflammation. Similar events and cross-talk with endothelium and smooth muscle will result in accelerated atherosclerosis and vasoconstriction [Figure 1].

Figure 1. The cardiac unit in abnormal homeostasis.

In the setting of advanced age, rate-limiting autophagy factors (e.g., Atg5 and LC3) are downregulated and flux is impaired. Excess insulin signaling and/or nutrient excess suppresses autophagy at transcriptional and post-translational levels. Loss of normal mitochondrial turnover results in the accumulation of mitochondria with distinctive oxidative posttranslational modifications including oxidized mitochondrial DNA (8-oxodG mtDNA). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) from these dysfunctional mitochondria drive NFκB signaling in cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells, and support inflammasome assembly in competent cell types (endothelial cells, tissue macrophages). The inability to clear damaged mitochondria in the setting of ischemic stress will abrogate cardioprotective interventions, while increased inflammatory signaling will exacerbate postinfarction remodeling, in part through stimulation of fibroblast proliferation. Upregulating autophagy restores homeostasis.

Impact of Aging on Autophagy and Inflammation

The maintenance of homeostasis is dependent upon the recognition of environmental changes as well as exposure to insult. “Danger-associated molecular patterns” (DAMPs), such as ROS, mitochondrial DNA and extracellular ATP, are detected by “pattern recognition receptors” (PRRs) that are comprised of several families, including “Toll-like receptors” (TLRs) and “Nod-like receptors” (NLRs). These molecules are not only involved in innate and adaptive immune responses, but they have been implicated in the control of autophagy and vice versa.

DAMPs shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome include extracellular ATP [80], cholesterol crystals [81, 82], hyaluronan [83], calcium phosphate crystals [84], amyloid-β [85], and ROS. In spite of the number of physically and chemically diverse stimuli that have been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, three non-exclusive but widely supported models by which the inflammasome is activated have been proposed [86]. These include extracellular ATP, lysosomal disruption, and ROS induction. During cell death, high concentrations of extracellular ATP have been shown to mediate intracellular potassium depletion and induce IL-1β secretion [87]. Extracellular ATP stimulates the purogenic P2X7 ATP-gated ion channel [88] triggering potassium efflux and inducing gradual recruitment of the pannexin-1 membrane pore [89]. Pore formation allows extracellular NLRP3 agonists to access the cytosol and directly activate NLRP3. The second model involves activators that form crystalline or particulate structures. These molecules disrupt lysosomes causing lysosomal particles/contents to leak into the cytosol and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [90]. In the third model, elevated ROS is observed upon treatment with NLRP3 activators [91, 92]; as such, it has been proposed that this common pathway engages the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Autophagy and inflammation are interdependent processes [93]. Cells with defects in autophagy accumulate damaged mitochondria and present increased levels of ROS, which results in increased levels of inflammatory cytokines. The production of IL-1β is dramatically affected by autophagy. Processing and activation of pro-IL-1β into its active form depends on the assembly of inflammasomes, and increased ROS levels seem to be a prerequisite for inflammasome activation. Inflammasomes are multimeric protein complexes that are comprised of a “sensor NLR” and function as platforms for the activation of pro-caspase-1, resulting in the processing and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18.

NLRP3 is one of several sensors but is unique in that it is activated by a wide array of host-derived and exogenous agonists. Mitochondria play an important role in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [94, 95]. Nakahira et al. [94] showed a role for mitochondrial DNA in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome while Zhou et al. [95] demonstrated the critical role for mitochondrial ROS. Shimada et al. [96] demonstrated that during programmed cell death cytosolic release of oxidized mitochondrial DNA binds to and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to generate IL-1β. Failure to clear damaged mitochondria through the autophagic pathway may lead to increased opportunities for release of oxidized mitochondrial DNA into the cytosol [Figure 2]. The generation of IL-1β requires two signals: 1. The production of the inactive pro-IL-1β form is mediated by TLR and consequent NFκB activation; 2. The processing of pro-IL-1β to its mature IL-1β form requires the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and activation of caspase-1. Importantly, the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome not only leads to IL-1β secretion but it can induce caspase 1-dependent cell death or pyroptosis, a highly inflammatory form of cell death characterized by both apoptosis and necrosis [97]. This can further exacerbate inflammation through the release of DAMPs.

Figure 2. Mitochondrial damage and inflammasome activation.

Mitochondrial damage leads to increased ROS production and oxidative damage to mtDNA. Damaged mitochondria are ordinarily cleared via mitophagy mediated by PINK1/parkin/p62, but if mitophagy is impaired by overnutrition or advanced age, then mtDNA with 8-oxoG modifications may be released into cytosol, where it can interact with TLR9 and the NLRP3 inflammasome to trigger IL-1 beta synthesis and processing.

Autophagy has been shown to regulate the magnitude of inflammation. Interventions including the use of autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA), deletion of LC3B or ATG16L1, silencing of Beclin-1, or dominant negative forms of the cysteine protease ATG4B lead to significantly higher levels of IL-1β [94, 98–100]. Autophagy controls inflammasomes by targeting its components to autophagosomes. It has been shown that pro-IL-1β is delivered to autophagosomes after TLR stimulation [98] and that NLRP3 inflammasomes containing ASC are directed to autophagosomes through ubiquitination [100].

Although it is known that autophagy declines with age, whether this leads to the increase in basal levels of inflammation, i.e., inflamm-aging, has yet to be determined. However, recent work by Dixit and colleagues suggest that the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome causes global age-related inflammation in multiple organs, with consequences such as thymic demise, impaired glycemic control, reduced memory and cognition, deteriorating motor performance, and bone loss [101]. Inflamm-aging is associated with many age-associated diseases, including cardiovascular disease. It is known that inflammation is a key process in the mediation of myocardial damage and repair post MI (reviewed in [102]). Previous studies have shown that targeting the inflammatory response improves MI outcome (reviewed in [103, 104]). The neutralizing antibody against IL-1β and Anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was shown to exert beneficial effects on acute MI in young animals [105, 106]. Kawaguchi et al. [107] demonstrated a role for inflammasomes during myocardial I/R injury using ASC-knockout (apoptosis-associated speck like protein: a scaffolding component of several inflammasomes, including the NLRP3 inflammasome) and caspase-1 knockout mice. They found the formation of inflammasomes post I/R as indicated by the detection of ASC in infiltrated neutrophils and macrophages as well as in vascular cells and cardiac resident fibroblasts. Furthermore, they found a significant decline in inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine/chemokine expression as well as a significant reduction of infarct size, myocardial fibrosis, and left ventricular dysfunction after MI in the ASC- or caspase-1-knockout mice. In bone marrow (BM) transplantation experiments (i.e., BM WT→ WT, BM ASC−/−→WT, and BM WT→ASC−/− chimeras), Kawaguchi et al. observed a reduction in infarct size following I/R in chimeras that lacked ASC in hematopoietic cells or non-hematopoietic cells suggesting the importance of inflammasomes in bone marrow derived inflammatory cells as well as in resident myocardial cells, i.e., cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts.

Using a murine model of permanent MI, Mezaroma et al. [108] reported that cardiomyocytes formed NLRP3 inflammasomes and that its activation induced caspase-1 dependent cardiomyocyte cell death, pyroptosis, but not IL-1β release. Importantly, they showed that inhibition of NLRP3 and the P2X7 receptor by small interfering RNA or a pharmacological inhibitor prevented inflammasome activation and cardiac cell death, and reduced remodeling post MI. P2X7 is a purinergic receptor ion channel that is activated by extracellular ATP released from injured cells, leading to potassium efflux and subsequent NLRP3 activation [80]. Using mouse and rat permanent MI models, Sandanger et al. [109] demonstrated that fibroblasts of the ischemic myocardium upregulate NLRP3 and secrete IL-1β in response to extracellular ATP released from damaged tissue. Langendorff-perfused hearts from NLRP3 knockout mice had preserved myocardial function and reduced infarct size after I/R compared to hearts isolated from wild type and ASC knockout mice. Although further analysis is needed to understand the basis for the difference in NLRP3 vs ASC knockouts, it is clear that the NLRP3 inflammasome exacerbates ischemic injury. Contrary to these findings, Zuurbier et al. [110] showed no improvement in either cardiac function or cell death in response to I/R in Langendorff-perfused hearts isolated from NLRP3 knockout mice. The reasons for the discrepancy are unclear but are discussed elsewhere [111, 112]. Taken together, the data suggest that cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts function in different roles (fibroblasts secrete IL-1β whereas cardiomyocytes do not secrete IL-1β but undergo pyroptosis), which contribute to cardiac inflammation and remodeling in MI.

Although a growing body of evidence indicates that the NLRP3 inflammasome-driven inflammatory responses contribute to the pathophysiology of MI, no reagents that specifically target NLRP3 are available. It should also be noted that despite the abundant literature on the NLRP3 inflammasome in monocytes/macrophages during inflammation, its contribution to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury is still emerging. Changes that may occur with aging or the role of autophagy in potentially regulating this process remain to be studied.

Autophagy in the Human Heart

Autophagy as an adaptive response to stress is undergoing intense investigation in an assortment of cellular and animal models. The growing interest in clinical relevance is not surprising given the increase in incidence and prevalence of neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases worldwide and the preclinical evidence suggesting that loss of adaptive autophagy is a common contributing factor. Dysfunctional or impaired autophagy has also been implicated in the exaggerated inflammatory process associated with Type II diabetes and aging [113]. Delineating the role of impaired autophagy in human disease is complicated by our limited ability to measure it. Examination of autophagic activity requires access to fresh tissue for western blot analysis, immunofluorescence microscopy, and/or electron microscopy. Nevertheless we do have some hints that cardiac autophagy is an active process in patients.

One of the first studies to suggest that autophagy is an adaptive process in the human heart was the report by Kassiotis et al [114]. Paired biopsies of the left ventricle were obtained from 9 patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy who were supported with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD). Biopsies were obtained at the time of implantation and removal of the LVAD. These investigators observed a downregulation in mRNA and protein levels of autophagy genes after prolonged support. They concluded that autophagy is an adaptive mechanism in the failing heart and is attenuated with circulatory support.

In 2012 Garcia et al. studied 170 patients who had undergone elective coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) and pre-operatively were in normal sinus rhythm [115]. During the operation right atrial biopsies were obtained for evaluation of remodeling by light and electron microscopy. Systemic inflammatory markers were measured at baseline and 72 hours after surgery. Protein ubiquitination and autophagy-related LC3B proteins were assessed by western blot. The investigators observed that 22% of the patients developed postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) and the level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, fibrosis, inflammation, myxoid degeneration, and ubiquitin-aggregates was similar between patients with and without POAF. Electron micrographs, however, showed an accumulation of autophagic vesicles and lipofuscin deposits in the biopsies of the patients with POAF. While the total protein ubiquitination was similar in the patients with and without POAF, LC3B processing was markedly reduced in those with POAF, suggesting a selective impairment in autophagic flux. The authors concluded that ultrastructural changes consistent with impaired autophagy were present in atrial biopsies of patients that developed POAF after CABG.

In 2010, our group initiated work on a translational research project to study the homeostatic intracellular repair response (HIR2), a clinical term used to characterize adaptive autophagy in the human heart. The Wayne State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all the protocols which involve human subjects. In patients undergoing heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), we collected a small amount of right atrial tissue (100 to 200 mg) at two time points: before initiation of CPB and aortic cross-clamping; and after removal of cross-clamp and weaning from CPB. Autophagic activity was assessed by western blot analysis of a variety of molecular markers.

In 2013, we (Jahania et al.) reported the results from the initial 19 patients regarding the effects of cardiac stress on the HIR2 [116]. We observed that ischemic stress was associated with a significant depletion of Beclin-1, ATG 5–12, LC3-II and p62. The difference in p62 levels measured at the time of aortic crossclamping and subsequent weaning from CPB correlated significantly with changes in Beclin-1, Atg5–12, LC3-I and LC3-II [116]. These findings point to a coordinated engagement of the autophagy machinery during cardiac stress and the depletion of autophagy proteins was interpreted to reflect increased autophagic flux. This interpretation, however, depends upon two assumptions: (1) the decrease in autophagy proteins was due to lysosomal (not proteasomal) degradation and (2) protein synthesis was generally suppressed during CPB.

The findings in the Jahania study are consistent with the report by Singh et al. [117]. These investigators examined patients undergoing heart surgery and obtained samples from right atrial appendages before cardioplegic arrest and after reperfusion. Tissue was submitted for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) array, quantitative real-time PCR, and immunoblot analysis for autophagy proteins and their associated upstream regulators. In this study, ischemia/reperfusion was associated with upregulation of 11 (13.1%) and downregulation of 3 (3.6%) of 84 autophagy related genes (ATG). Specifically, there were increases in ATG4A, ATG4C, ATG4D, and GABARAPL2. This study is important because it provides information on both mRNA and protein, a limitation of the other human studies. Autophagic activity was confirmed through observations of higher LC3-I levels and an increase in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio. As expected, the activation of autophagy was accompanied by phosphorylation of AMPK and dephosphorylation of mTOR. They concluded that gene expression and post-translational regulation of autophagy in the human heart is affected by ischemia/reperfusion and went on to speculate that the findings could lead to autophagy-targeted therapeutic approaches to limit cardiac injury.

In contrast to the evidence that cardiac autophagy is activated in humans in response to ischemia/reperfusion, Gedik et al. [118] reported that autophagy was not associated with protection conferred by remote ischemic preconditioning (RIPC) in patients undergoing CABG surgery. In this study, left ventricular biopsies were available from 20 CABG patients (10 RIPC and 10 placebo patients) who were previously enrolled in a large randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy of RIPC in conferring intraoperative myocardial protection. Transmural myocardial biopsies of the left ventricle from the territory undergoing revascularization were taken before initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and at 5–10 min reperfusion. The investigators failed to observe differences in the abundance of key autophagy proteins either with ischemia/reperfusion or between the placebo and RIPC cohorts despite evidence of RIPC-induced protection manifest as a reduction in serum cTnI. There were important differences however between this study and the one reported by Jahania et al. The sample size was smaller, biopsies were taken from the left ventricle, the duration of ischemia/reperfusion was shorter, and paired analysis was not reported. In the Jahania study, each patient’s paired before and after ischemia results were reported as a delta value after normalizing to actin. Actin was chosen because it is less subject to acute metabolic changes compared to the metabolic enzyme GAPDH used in the Gedik study. The Gedik study reported the mean baseline (before cross clamp) compared to the mean value at 10min reperfusion, and may have missed individual pre-post changes. Another possible explanation for the failure to detect changes in autophagy proteins in these left ventricle samples is that they were from a region of the heart that was ischemic even at baseline; it might have been impossible for the already-ischemic tissue to further upregulate autophagy in response to the added stress of CPB. Nevertheless, this study, which is the only one to examine left ventricle in human patients, raises concern that differences in autophagy may exist between atria and ventricles. While the majority of observations to date suggest that cardiac autophagy is an active and adaptive response in humans, additional studies are needed to confirm these findings and determine whether enhancement of HIR2 will open the door to new cardioprotective strategies.

Cardiac Autophagy and Aging

There is considerable evidence from preclinical studies that aging is associated with diminished autophagy [119]. As noted earlier, there is evidence to suggest that genetic attenuation of autophagy induces changes in animals that resemble those seen with advanced age. Likewise, stimulation of autophagy via caloric restriction, Sirtuin-1 activation, inhibition of insulin and insulin-like growth factor signaling and the administration of rapamycin and spermidine have all been reported to increase life span [50, 120–123]. Interestingly, one of the key anti-aging interventions that extends life span in most animals tested is caloric restriction, the most potent physiological inducer of autophagy [124]. Despite these observations, very little is known about age-related changes in autophagy in the human heart.

To begin to address this question, we increased the sample size in the original Jahania study [116] from 19 patients to 38 [125]. In this cohort of patients, the average age was 62yr and ranged between 33–87yr [Table 1]. Right atrial biopsies were obtained as before and lipidation of the autophagy protein LC3 (conversion from LC3-I to LC3-II) was monitored by immunoblotting. The LC3 Index was calculated by dividing the LC3-II/I ratio after CPB by the ratio before CPB initiation. We used the LC3 Index to measure time-dependent changes in the synthesis of LC3-I, conversion to LC3-II, and lysosomal degradation of LC3-II. We also used the index as a marker of autophagic flux during CPB. The analysis was completed on 38 biopsies before CPB and 37 biopsies after CPB. Consistent with our previous report [116], cardiac stress in the setting of heart surgery with CPB was associated with significant autophagic flux. When the data was examined in the context of age, we observed that increasing age was associated with a higher LC3 Index. We also assessed changes in the LC3-II/I ratio as a function of time and found that for each 10 minute increase in ischemic time, the LC3 Index increased by 3%. Although ischemic time was associated with the LC3 Index, age did not affect this relationship. The decrease in LC3-I during CPB is attributed to inadequate production of LC3-I, inadequate delipidation of LC3-II, and/or increased LC3 lipidation. The increase in LC3-II may be due to increased LC3 lipidation, impaired delipidation of LC3-II, and/or impaired lysosomal clearance of LC3-II. Delipidation of LC3-II is mediated by Atg4, whose enzymatic activity is inhibited by ROS. While the LC3-II/I ratio as a measure of autophagic activity is regarded as a controversial measure of autophagy, time-dependent changes in the ratio (LC3 Index) in biopsies from the same patient may be informative. Interestingly, the increase in the LC3 Index suggests that older patients are still capable of mounting a robust autophagic response. This differs from what has been reported in aged animal studies [119]. However, these patients were deemed to be vigorous enough to withstand the stresses of cardiac surgery based on preoperative screening including relatively normal preoperative ventricular function. The findings suggest that in this cohort of patients, ischemic stress can elicit a robust autophagic response that is age independent. If confirmed in future studies, the homeostatic intracellular repair response could become an important therapeutic target regardless of age.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 38 cardiac surgery patients.

| Variable | Average |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62 ± 13 |

| Males (%) | 87% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 ± 6 |

| Dyslipidemia | 79% |

| HbA1c (mean %) | 6.6 ± 1.8 |

| Previous MI (%) | 40 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 53 ± 8.7 |

| Aortic Cross-clamp time (min) | 108 ± 40 |

| Type of operation and number of patients | |

| CABG | 23 |

| Valve | 11 |

| CABG & Valve | 3 |

Impact of Diabetes on Cardiac Autophagy

There is preclinical evidence that autophagy is compromised in animals with features of metabolic syndrome (MetS), a condition associated with obesity, dyslipidemia, elevated fasting blood glucose levels and insulin resistance [126]. Likewise, type II diabetes (T2DM) has been associated with impaired autophagy in various animal models [113]. This is not surprising given that MetS and Type 2 diabetes both represent excess nutrient conditions with active mTOR and suppression of autophagy. The nutrient sensor mTOR participates in the dynamic regulation of autophagy: it potently suppresses autophagy through phosphorylation of an inhibitory site on ULK1. During nutrient deprivation, mTOR is inactivated by AMPK. As autophagic flux proceeds, mTOR, which is associated with the lysosome, is reactivated by leucine generated by lysosomal degradation, and suppresses further autophagy, closing the feedback loop. Dysregulation of mTOR can arise if autophagic flux or lysosomal function is impaired.

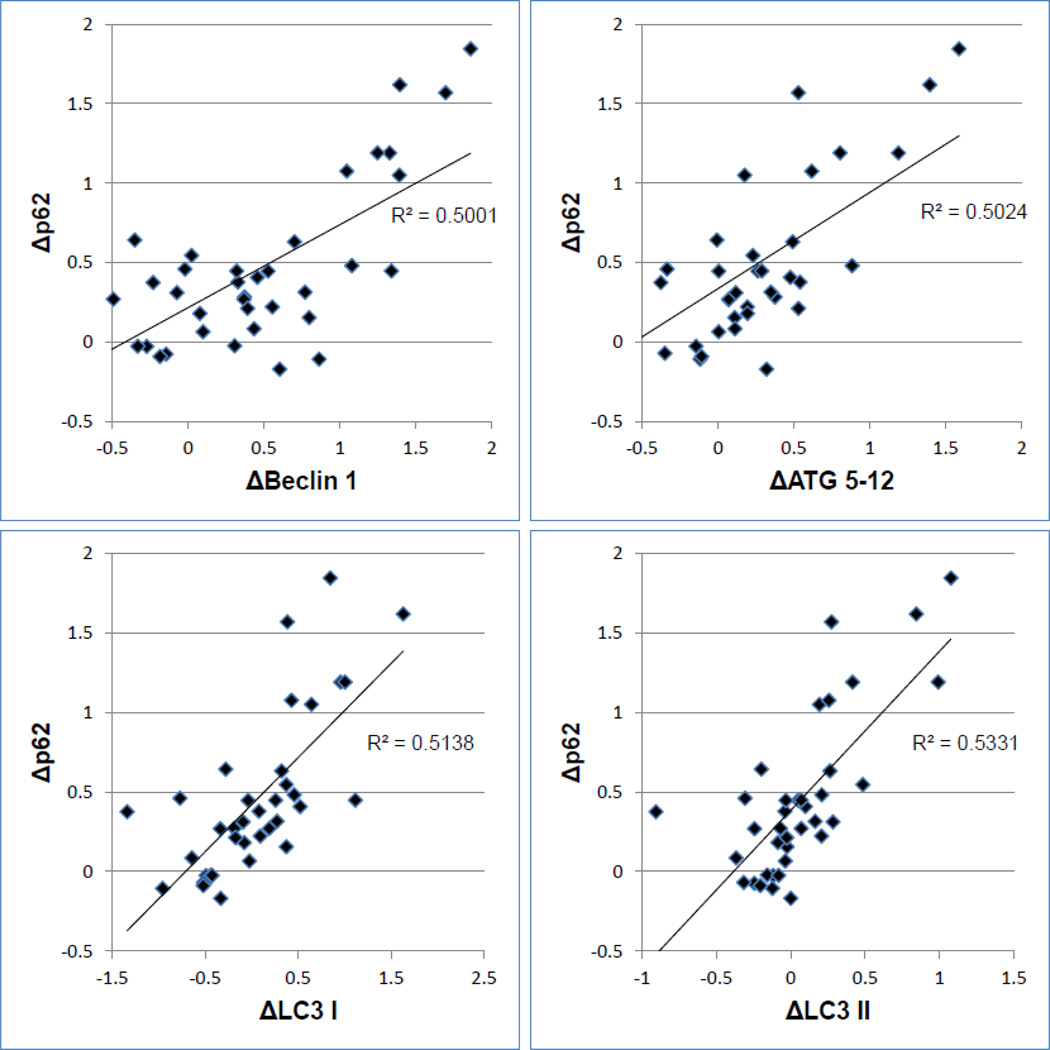

Very little is known about the effects of diabetes on the HIR2 in humans. Using the Jahania expanded data set (n=38 patients); we asked the question whether HIR2 is impaired in patients with poorly controlled diabetes. We used the Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ database to identify the patients with T2DM (n=15) and HbA1c levels as a marker of diabetic control: patient HbA1c levels greater than 7% prior to surgery were deemed to represent a poorly controlled subset. As before, the HIR2 was assessed by measuring Beclin-1, LC3-I, LC3-II, and p62 in the right atrial biopsies before initiation and after weaning from CPB. The pre-post difference in p62 (Δp62) was used to assess autophagic activity during surgery. The demographics of the cardiac surgery patients and their diabetic status are shown in [Table 1].

Altogether, 23 nondiabetic and 15 diabetic patients were evaluated. The average HbA1c level in the nondiabetic and diabetic patients was 5.6% and 8.0%, respectively. Ten of the diabetic patients had HbA1c levels greater than 7%. Consistent with the original study [116], heart surgery with CPB was associated with a marked decrease in Beclin-1 and p62 [Figure 3]. Δp62 also correlated with ΔBeclin-1, ΔLC3-I and ΔLC3-II. These findings were interpreted to indicate a robust autophagic response. While there was no relationship between the HbA1c value and Δp62 in the non-diabetic patient cohort, in the T2DM patients, there was a significant inverse relationship between Δp62 and HbA1c [Figure 4]. Interestingly the autophagic response in all diabetic patients was comparable to the non-diabetics. However, among diabetics with poor glycemic control (HgbA1c >7.0 %), the autophagic response was impaired. These findings support the concept that T2DM adversely affects adaptive autophagy in the human heart and implicate a pathophysiological process that may be involved in the increased susceptibility of diabetic patients to myocardial ischemia.

Figure 3. Correlations between p62 and other markers of autophagy.

The delta value refers to the difference in abundance (detected by western blotting) from beginning of aortic cross-clamp to end. All values normalized to actin levels. A larger delta value reflects greater autophagic flux. P<0.0001 for all correlations.

Figure 4. Relationship between Δp62 and HbA1c in diabetic cardiac surgery patients.

Delta p62 from beginning to end of cross-clamp was determined by western blot after normalizing to actin, and plotted against HgbA1c values in the diabetic patients (p = 0.030, n=15).

Clinical Implications

Ischemic preconditioning is widely studied as a powerful cardioprotective intervention [127, 128]. We previously showed that ischemic and pharmacologic preconditioning depend upon autophagy for their ability to protect the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury [129–131], and autophagy targeting mitochondria is specifically required for protection [132]. Other cardioprotective interventions such as chloramphenicol [133], caloric restriction [134] simvastatin [135], SAHA [136], and rapamycin [136, 137] also involve autophagy. Early work by Vatner’s group showed that autophagy was upregulated in hibernating myocardium, and that autophagy markers did not colocalize with apoptosis, suggesting that autophagy was a protective response to ischemic stress [138]. One study using Beclin-1 haploinsufficient mice concluded that autophagy was protective during ischemia but deleterious during reperfusion, because Beclin-1 was upregulated during reperfusion and Beclin-1+/− mice had smaller infarcts [139]. In contrast, chloramphenicol administered to pigs potently upregulated Beclin-1 yet reduced infarct size substantially, even when given at reperfusion [133]. The confusion surrounding Beclin-1 may be due to its roles in promoting canonical and non-canonical autophagy as well as regulating lysosome autophagosome fusion, where, in partnership with Rubicon, it can impede flux [140]. In the stressed heart, it appears that Beclin-1 haploinsufficiency alleviates the impediment to flux, resulting in accelerated autophagy [141]. Selective autophagy targeting mitochondria is also important for cardiac homeostasis. Ischemia/reperfusion injury is exacerbated by deletion of Parkin or PINK1 [142, 143], and we have demonstrated Parkin’s role in ischemic preconditioning [132].

The role of autophagy in pressure overload hypertrophy and heart failure has been less clear. Loss of autophagy (inducible deletion of Atg5 in adult mice) results in heart failure [144], and upregulation of autophagy by exercise or Atg7 overexpression ameliorates desmin-related cardiomyopathy [145]. Cardiac-specific (constitutive) deletion of Atg5 exacerbated pressure overload hypertrophy [144]. However, Beclin-1 haploinsufficient mice exhibited some protection from pressure-overload hypertrophy, leading the authors to conclude that autophagy was maladaptive [146]. However, if re-interpreted in light of Diwan’s findings that the Beclin-1+/− mice have accelerated autophagic flux [141], then the two studies are not contradictory. Rapamycin has also been shown to ameliorate heart failure in chronic models [147]. Taken together, these observations support a beneficial role for autophagy in the heart.

Cardiac dysfunction is exacerbated by conditions in which autophagy/mitophagy is impaired. Obesity [2] and diabetes [148] amplify mTOR signaling cascades that suppress autophagy. High fat diets are associated with impaired autophagy [2] and mitochondrial dysfunction [149, 150], and are well known to increase myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury [151, 152].

Autophagy may not always be good for the heart. Autophagic machinery supports replication and dissemination of coxsackievirus B, a virus responsible for myocarditis and heart failure [153, 154]. Excessive autophagy may also contribute to doxorubicin-mediated cardiac injury [155, 156], although other studies reported a beneficial role for autophagy [78, 157–159]. Doxorubicin toxicity was exacerbated by deletion of Nrf2, a transcriptional regulator of autophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis, but this was rescued by overexpression of Atg5 [160].

Despite the wide variety of diseases affected by autophagy and the implications for modulating these diseases, we know very little about the function of autophagy in humans. The translation of the clinical and pre-clinical findings described above into clinical studies is just beginning. Currently, only 37 phase I/II clinical trials that use the keyword “autophagy” are listed on ClinicalTrials.gov. The majority of these (29 of 37) are in the field of oncology; only one is in cardiac disease. Despite the limited knowledge of how autophagy affects the human heart, animal data and our preliminary human studies suggest autophagy is activated during the process of ischemia-reperfusion. Although there are no approved therapies to treat I/R injury, modulation of autophagy, a process that protects cells under stress, holds tremendous promise for ameliorating age-related cardiac pathologies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 38 cardiac surgery patients by diabetes status.

| Variable | Non-Diabetics (n=25) | Diabetics (n=15) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61±14 | 63±12 | p>0.2 |

| Males (%) | 87% | 87% | p>0.2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30±6.5 | 32±5.5 | p>0.2 |

| Dyslipidemic (%) | 70% | 93% | p=0.05 |

| HbA1c (mean %) | 5.6±0.44 | 8.0±2.1 | p=0.0005 |

| Previous MI (%) | 39% | 40% | p>0.2 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 52±10 | 54±6.0 | p>0.2 |

| Aortic Cross-clamp time (min) | 115±42 | 99±35 | p>0.2 |

| Procedure: | p>0.2 | ||

| CABG | 57% | 73% | |

| Valve | 35% | 20% | |

| CABG & Valve | 6% | 8% | |

A mito decayed and leaked DNA

Plus cytochrome c and 8-oxo-dG

The inflammasome blew

And the apoptosome too

And the cell had a very bad day.

THIS OLD HEART (highlights).

As you age autophagy slows down, debris builds up and cells turn brown.

Lipofuscin the scum that marks aged cells, remnants of lysosomes gone to hell.

When mitos decay they leak DNA, cytochrome c and oxo-dG.

Cell death is what follows or cruel inflammation: either fate is cell condemnation.

But if you recycle your organelles you’ll have more years of living well.

Acknowledgements

This was supported in part by NHLBI P01 11-2730 (to RAG, RMM, PJL). RAG appreciates the support of the Dorothy and E. Phillip Lyon Chair in Molecular Cardiology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Literature Cited

- 1.Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ren SY, Xu X. Role of autophagy in metabolic syndrome-associated heart disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka K, Matsuda N. Proteostasis and neurodegeneration: the roles of proteasomal degradation and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malicdan MC, Noguchi S, Nishino I. Monitoring autophagy in muscle diseases. Methods Enzymol. 2009;453:379–396. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang ZJ, Chee CE, Huang S, Sinicrope FA. The role of autophagy in cancer: therapeutic implications. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2011;10:1533–1541. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Meyer GR, Martinet W. Autophagy in the cardiovascular system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1485–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quan W, Lee MS. Role of autophagy in the control of body metabolism. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea) 2013;28:6–11. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2013.28.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deretic V, Saitoh T, Akira S. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13:722–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuk JM, Yoshimori T, Jo EK. Autophagy and bacterial infectious diseases. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2012;44:99–108. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudchodkar SB, Levine B. Viruses and autophagy. Reviews in medical virology. 2009;19:359–378. doi: 10.1002/rmv.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider JL, Cuervo AM. Autophagy and human disease: emerging themes. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2014;26C:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li WW, Li J, Bao JK. Microautophagy: lesser-known self-eating. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:1125–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0865-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mijaljica D, Prescott M, Devenish RJ. Different fates of mitochondria: alternative ways for degradation? Autophagy. 2007;3:4–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Waal EJ, Vreeling-Sindelarova H, Schellens JP, James J. Starvation-induced microautophagic vacuoles in rat myocardial cells. Cell biology international reports. 1986;10:527–533. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(86)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takikita S, Myerowitz R, Zaal K, Raben N, Plotz PH. Murine muscle cell models for Pompe disease and their use in studying therapeutic approaches. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;96:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dice JF, Terlecky SR, Chiang HL, Olson TS, Isenman LD, Short-Russell SR, et al. A selective pathway for degradation of cytosolic proteins by lysosomes. Seminars in cell biology. 1990;1:449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandyopadhyay U, Kaushik S, Varticovski L, Cuervo AM. The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5747–5763. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02070-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aniento F, Roche E, Cuervo AM, Knecht E. Uptake and degradation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by rat liver lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10463–10470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiffin R, Christian C, Knecht E, Cuervo AM. Activation of chaperone-mediated autophagy during oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4829–4840. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. Age-related decline in chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31505–31513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiffin R, Kaushik S, Zeng M, Bandyopadhyay U, Zhang C, Massey AC, et al. Altered dynamics of the lysosomal receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy with age. Journal of cell science. 2007;120:782–791. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang C, Cuervo AM. Restoration of chaperone-mediated autophagy in aging liver improves cellular maintenance and hepatic function. Nat Med. 2008;14:959–965. doi: 10.1038/nm.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takemura G, Kanamori H, Goto K, Maruyama R, Tsujimoto A, Fujiwara H, et al. Autophagy maintains cardiac function in the starved adult. Autophagy. 2009;5:1034–1036. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Autophagy in ischemic heart disease. Circ Res. 2009;104:150–158. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reggiori F, Komatsu M, Finley K, Simonsen A. Selective types of autophagy. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:156272. doi: 10.1155/2012/156272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1383–1435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baek KH, Park J, Shin I. Autophagy-regulating small molecules and their therapeutic applications. Chemical Society reviews. 2012;41:3245–3263. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15328a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2011;27:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanware NP, Bray K, Abraham RT. The PI3K, metabolic, and autophagy networks: interactive partners in cellular health and disease. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2013;53:89–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, Chandra P, Roderick HL, Habermann A, et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayashi-Nishino M, Fujita N, Noda T, Yamaguchi A, Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A. A subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum forms a cradle for autophagosome formation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1433–1437. doi: 10.1038/ncb1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yla-Anttila P, Vihinen H, Jokitalo E, Eskelinen EL. 3D tomography reveals connections between the phagophore and endoplasmic reticulum. Autophagy. 2009;5:1180–1185. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.8.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK, et al. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ravikumar B, Moreau K, Jahreiss L, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:747–757. doi: 10.1038/ncb2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otomo C, Metlagel Z, Takaesu G, Otomo T. Structure of the human ATG12~ATG5 conjugate required for LC3 lipidation in autophagy. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20:59–66. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tooze SA, Yoshimori T. The origin of the autophagosomal membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:831–835. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartlett BJ, Isakson P, Lewerenz J, Sanchez H, Kotzebue RW, Cumming RC, et al. p62, Ref(2)P and ubiquitinated proteins are conserved markers of neuronal aging, aggregate formation and progressive autophagic defects. Autophagy. 2011;7:572–583. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.14943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clausen TH, Lamark T, Isakson P, Finley K, Larsen KB, Brech A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 and ALFY interact to facilitate the formation of p62 bodies/ALIS and their degradation by autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:330–344. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.3.11226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin-induced mitophagy in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. Autophagy. 2009;5:706–708. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A, Reddy VA, Orth A, et al. Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simonsen A, Cumming RC, Brech A, Isakson P, Schubert DR, Finley KD. Promoting basal levels of autophagy in the nervous system enhances longevity and oxidant resistance in adult Drosophila. Autophagy. 2008;4:176–184. doi: 10.4161/auto.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pyo JO, Yoo SM, Ahn HH, Nah J, Hong SH, Kam TI, et al. Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nature communications. 2013;4:2300. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madeo F, Tavernarakis N, Kroemer G. Can autophagy promote longevity? Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:842–846. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaeberlein M, Burtner CR, Kennedy BK. Recent developments in yeast aging. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e84. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Speakman JR, Mitchell SE. Caloric restriction. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2011;32:159–221. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morselli E, Maiuri MC, Markaki M, Megalou E, Pasparaki A, Palikaras K, et al. Caloric restriction and resveratrol promote longevity through the Sirtuin-1-dependent induction of autophagy. Cell death & disease. 2010;1:e10. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bjedov I, Toivonen JM, Kerr F, Slack C, Jacobson J, Foley A, et al. Mechanisms of life span extension by rapamycin in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2010;11:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alvers AL, Wood MS, Hu D, Kaywell AC, Dunn WA, Jr, Aris JP. Autophagy is required for extension of yeast chronological life span by rapamycin. Autophagy. 2009;5:847–849. doi: 10.4161/auto.8824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Liu J, Bruns NE, et al. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3374–3379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712145105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dai DF, Chiao YA, Marcinek DJ, Szeto HH, Rabinovitch PS. Mitochondrial oxidative stress in aging and healthspan. Longevity & healthspan. 2014;3:6. doi: 10.1186/2046-2395-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rezzani R, Stacchiotti A, Rodella LF. Morphological and biochemical studies on aging and autophagy. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11:10–31. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Judge S, Jang YM, Smith A, Hagen T, Leeuwenburgh C. Age-associated increases in oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activities in cardiac interfibrillar mitochondria: implications for the mitochondrial theory of aging. FASEB J. 2005;19:419–421. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2622fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mammucari C, Rizzuto R. Signaling pathways in mitochondrial dysfunction and aging. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2010;131:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, Masiero E, Rudolf R, Del Piccolo P, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007;6:458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Terman A, Brunk UT. Autophagy in cardiac myocyte homeostasis, aging, and pathology. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terman A, Kurz T, Navratil M, Arriaga EA, Brunk UT. Mitochondrial turnover and aging of long-lived postmitotic cells: the mitochondrial-lysosomal axis theory of aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:503–535. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Misra MK, Sarwat M, Bhakuni P, Tuteja R, Tuteja N. Oxidative stress and ischemic myocardial syndromes. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2009;15:RA209–RA219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li L, Chen Y, Gibson SB. Starvation-induced autophagy is regulated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species leading to AMPK activation. Cell Signal. 2013;25:50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. Embo J. 2007;26:1749–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taneike M, Yamaguchi O, Nakai A, Hikoso S, Takeda T, Mizote I, et al. Inhibition of autophagy in the heart induces age-related cardiomyopathy. Autophagy. 2010;6:600–606. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.11947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martinez-Vicente M, Sovak G, Cuervo AM. Protein degradation and aging. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:622–633. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brunk UT, Jones CB, Sohal RS. A novel hypothesis of lipofuscinogenesis and cellular aging based on interactions between oxidative stress and autophagocytosis. Mutat Res. 1992;275:395–403. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90042-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gottlieb RA, Carreira RS. Autophagy in health and disease. 5. Mitophagy as a way of life. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C203–C210. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00097.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rajawat YS, Hilioti Z, Bossis I. Aging: central role for autophagy and the lysosomal degradative system. Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8:199–213. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wohlgemuth SE, Julian D, Akin DE, Fried J, Toscano K, Leeuwenburgh C, et al. Autophagy in the heart and liver during normal aging and calorie restriction. Rejuvenation research. 2007;10:281–292. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boyle AJ, Shih H, Hwang J, Ye J, Lee B, Zhang Y, et al. Cardiomyopathy of aging in the mammalian heart is characterized by myocardial hypertrophy, fibrosis and a predisposition towards cardiomyocyte apoptosis and autophagy. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uddin MN, Nishio N, Ito S, Suzuki H, Isobe K. Autophagic activity in thymus and liver during aging. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlands) 2012;34:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Inuzuka Y, Okuda J, Kawashima T, Kato T, Niizuma S, Tamaki Y, et al. Suppression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase prevents cardiac aging in mice. Circulation. 2009;120:1695–1703. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.871137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vittorini S, Paradiso C, Donati A, Cavallini G, Masini M, Gori Z, et al. The age-related accumulation of protein carbonyl in rat liver correlates with the age-related decline in liver proteolytic activities. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 1999;54:B318–B323. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.8.b318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karamanlidis G, Bautista-Hernandez V, Fynn-Thompson F, del Nido P, Tian R. Impaired Mitochondrial Biogenesis Precedes Heart Failure in Right Ventricular Hypertrophy in Congenital Heart Disease. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2011;4:707–713. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.961474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoshino A, Mita Y, Okawa Y, Ariyoshi M, Iwai-Kanai E, Ueyama T, et al. Cytosolic p53 inhibits Parkin-mediated mitophagy and promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in the mouse heart. Nature communications. 2013;4:2308. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kubli DA, Quinsay MN, Gustafsson AB. Parkin deficiency results in accumulation of abnormal mitochondria in aging myocytes. Communicative & integrative biology. 2013;6:e24511. doi: 10.4161/cib.24511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O'Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rajamaki K, Lappalainen J, Oorni K, Valimaki E, Matikainen S, Kovanen PT, et al. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamasaki K, Muto J, Taylor KR, Cogen AL, Audish D, Bertin J, et al. NLRP3/cryopyrin is necessary for interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) release in response to hyaluronan, an endogenous trigger of inflammation in response to injury. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12762–12771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806084200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pazar B, Ea HK, Narayan S, Kolly L, Bagnoud N, Chobaz V, et al. Basic calcium phosphate crystals induce monocyte/macrophage IL-1beta secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro. J Immunol. 2011;186:2495–2502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perregaux D, Gabel CA. Interleukin-1 beta maturation and release in response to ATP and nigericin. Evidence that potassium depletion mediated by these agents is a necessary and common feature of their activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15195–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kahlenberg JM, Dubyak GR. Mechanisms of caspase-1 activation by P2X7 receptor-mediated K+ release. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1100–C1108. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00494.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Kim YG, Chen G, Park JH, Franchi L, et al. Pannexin-1-mediated recognition of bacterial molecules activates the cryopyrin inflammasome independent of Toll-like receptor signaling. Immunity. 2007;26:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fubini B, Hubbard A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) generation by silica in inflammation and fibrosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1507–1516. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cruz CM, Rinna A, Forman HJ, Ventura AL, Persechini PM, Ojcius DM. ATP activates a reactive oxygen species-dependent oxidative stress response and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2871–2879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608083200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:222–230. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Dagvadorj J, Chiba N, Chen S, et al. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity. 2012;36:401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2009;7:99–109. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harris J, Hartman M, Roche C, Zeng SG, O'Shea A, Sharp FA, et al. Autophagy controls IL-1beta secretion by targeting pro-IL-1beta for degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9587–9597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saitoh T, Fujita N, Jang MH, Uematsu S, Yang BG, Satoh T, et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature. 2008;456:264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature07383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shi CS, Shenderov K, Huang NN, Kabat J, Abu-Asab M, Fitzgerald KA, et al. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1beta production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Youm YH, Grant RW, McCabe LR, Albarado DC, Nguyen KY, Ravussin A, et al. Canonical Nlrp3 inflammasome links systemic low-grade inflammation to functional decline in aging. Cell Metab. 2013;18:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marchant DJ, Boyd JH, Lin DC, Granville DJ, Garmaroudi FS, McManus BM. Inflammation in myocardial diseases. Circ Res. 2012;110:126–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hwang MW, Matsumori A, Furukawa Y, Ono K, Okada M, Iwasaki A, et al. Neutralization of interleukin-1beta in the acute phase of myocardial infarction promotes the progression of left ventricular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1546–1553. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01591-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Abbate A, Salloum FN, Vecile E, Das A, Hoke NN, Straino S, et al. Anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, inhibits apoptosis in experimental acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:2670–2683. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kawaguchi M, Takahashi M, Hata T, Kashima Y, Usui F, Morimoto H, et al. Inflammasome activation of cardiac fibroblasts is essential for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2011;123:594–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mezzaroma E, Toldo S, Farkas D, Seropian IM, Van Tassell BW, Salloum FN, et al. The inflammasome promotes adverse cardiac remodeling following acute myocardial infarction in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19725–19730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108586108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sandanger O, Ranheim T, Vinge LE, Bliksoen M, Alfsnes K, Finsen AV, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is up-regulated in cardiac fibroblasts and mediates myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:164–174. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zuurbier CJ, Jong WM, Eerbeek O, Koeman A, Pulskens WP, Butter LM, et al. Deletion of the innate immune NLRP3 receptor abolishes cardiac ischemic preconditioning and is associated with decreased Il-6/STAT3 signaling. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Takahashi M. NLRP3 inflammasome as a novel player in myocardial infarction. International heart journal. 2014;55:101–105. doi: 10.1536/ihj.13-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jong WM, Zuurbier CJ. A role for NLRP3 inflammasome in acute myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury? Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:226. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Riehle C, Abel ED. Insulin regulation of myocardial autophagy. Circ J. 2014;78:2569–2576. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-14-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kassiotis C, Ballal K, Wellnitz K, Vela D, Gong M, Salazar R, et al. Markers of autophagy are downregulated in failing human heart after mechanical unloading. Circulation. 2009;120:S191–S197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Garcia L, Verdejo HE, Kuzmicic J, Zalaquett R, Gonzalez S, Lavandero S, et al. Impaired cardiac autophagy in patients developing postoperative atrial fibrillation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012;143:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Jahania SM, Sengstock D, Vaitkevicius P, Andres A, Ito BR, Gottlieb RA, et al. Activation of the homeostatic intracellular repair response during cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.034. discussion 26-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Singh KK, Yanagawa B, Quan A, Wang R, Garg A, Khan R, et al. Autophagy gene fingerprint in human ischemia and reperfusion. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2014;147:1065–1072.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gedik N, Thielmann M, Kottenberg E, Peters J, Jakob H, Heusch G, et al. No evidence for activated autophagy in left ventricular myocardium at early reperfusion with protection by remote ischemic preconditioning in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. SIRT1: regulation of longevity via autophagy. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1356–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Eisenberg T, Knauer H, Schauer A, Buttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Carmona-Gutierrez D, et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1305–1314. doi: 10.1038/ncb1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cox LS, Mattison JA. Increasing longevity through caloric restriction or rapamycin feeding in mammals: common mechanisms for common outcomes? Aging Cell. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gomez TA, Clarke SG. Autophagy and insulin/TOR signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans pcm-1 protein repair mutants. Autophagy. 2007;3:357–359. doi: 10.4161/auto.4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sengstock D, Jahania S, Andres A, Ito BR, Gottlieb RA, Mentzer RM., Jr Homeostatic Intracellular Repair Response (HIR2) Is Increased in Older Adults and Is Upregulated by Ischemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:S108. [Google Scholar]