Abstract

Land application of cattle slurry can result in incidental and chronic phosphorus (P) loss to waterbodies, leading to eutrophication. Chemical amendment of slurry has been proposed as a management practice, allowing slurry nutrients to remain available to plants whilst mitigating P losses in runoff. The effectiveness of amendments is well understood but their impacts on other loss pathways (so-called ‘pollution swapping’ potential) and therefore the feasibility of using such amendments has not been examined to date. The aim of this laboratory scale study was to determine how the chemical amendment of slurry affects losses of NH3, CH4, N2O, and CO2. Alum, FeCl2, Polyaluminium chloride (PAC)- and biochar reduced NH3 emissions by 92, 54, 65 and 77% compared to the slurry control, while lime increased emissions by 114%. Cumulative N2O emissions of cattle slurry increased when amended with alum and FeCl2 by 202% and 154% compared to the slurry only treatment. Lime, PAC and biochar resulted in a reduction of 44, 29 and 63% in cumulative N2O loss compared to the slurry only treatment. Addition of amendments to slurry did not significantly affect soil CO2 release during the study while CH4 emissions followed a similar trend for all of the amended slurries applied, with an initial increase in losses followed by a rapid decrease for the duration of the study. All of the amendments examined reduced the initial peak in CH4 emissions compared to the slurry only treatment. There was no significant effect of slurry amendments on global warming potential (GWP) caused by slurry land application, with the exception of biochar. After considering pollution swapping in conjunction with amendment effectiveness, the amendments recommended for further field study are PAC, alum and lime. This study has also shown that biochar has potential to reduce GHG losses arising from slurry application.

Introduction

The land application of dairy cattle slurry to farmland can result in incidental and chronic phosphorus (P) losses to a waterbody [1] resulting in eutrophication [2]. Incidental P losses take place when a rainfall event occurs shortly after slurry application and before slurry infiltration into the soil, while chronic P losses are a long-term loss of P from the soil as a result of a build-up in soil test P (STP) caused by application of inorganic fertilisers and manure [1]. Previous studies have indicated that that even with no additional P inputs, it can take up to 20 yr in soils of high STP to reduce to acceptable limits [3,4,5,6]. It is largely accepted that supplementary measures, in particular the development of P mitigating technologies, will be necessary to address the time lag between implementation of these strategies and reduction of STP to the appropriate levels.

Reactive nitrogen (N) losses from slurry also pose significant environmental risks. which is applied in excess of crop requirements can be converted in the soil through mineralization, and processes of nitrification and de-nitrification. Gaseous N loss from slurry due to the volatilisation of ammonia (NH3) is the major N loss pathway from slurry, resulting in a 50%-80% loss of total ammoniacal nitrogen (TAN). This represents both a considerable reduction in the N fertiliser value of slurry and a considerable source of atmospheric pollution as ammonia is both an acidifying gas and a source of terrestrial and aquatic eutrophication following deposition [7, 8, 9,10]. In addition, landspreading can increase emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG), particularly nitrous oxide (N2O) [11 12], but also carbon dioxide (CO2) [13, 14] and methane (CH4) [15].

Currently, Irish agriculture accounts for 32.1% of all national GHG emissions [16] and for virtually all NH3 emissions [17]. Whilst CH4 from enteric fermentation comprises the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions, N2O - associated with N inputs to soils—comprise the second-largest source (36.5%). Nitrous oxide, in turn, contributes to both global warming, due to its high global warming potential (296 times that of CO2), and also stratospheric ozone depletion [18, 19]. Although NH3 is not a GHG, it contributes to acidification of soils, atmospheric pollution and eutrophication of surface and ground water systems [20]. An estimated 5% of global N2O emissions results as a consequence of wet and dry deposition of NH3 and subsequent nitrification/denitrification [21]. Approximately 40 million tonnes (Mt) of animal manures are produced annually in Ireland resulting in a national emissions of 103.7 kt NH3. Landspreading of manures accounts for 35% of this total [16]. However, it is anticipated that these emissions may rise in the future, due to the fact that dairy sector expansion may result from milk quotas being abolished within the European Union. [22].

Chemical amendment of dairy cattle slurry before land application has been proposed as a strategy to mitigate P losses by reducing the solubility of P in slurry [23, 24]. The most effective chemicals at reducing dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP) from overlying water have been shown to be (from best to worst) alum, poly-aluminium chloride (PAC), ferric chloride (FeCl2), and lime, once all associated costs have been taken into account.

Recent research on the use of biochar (pyrolysed organic material) as a soil amendment has shown its beneficial effects on soil fertility [25, 26] and at reducing greenhouse gas emissions [27, 28]. In particular, it may help retain ammonium in fertilizer and lower gaseous N emissions [26, 27]. In addition, biochar has been proposed as a potential P mitigation amendment with a 50% reduction of soluble P and an increase in plant available P reported for dairy slurry lagoons [29]. Therefore, there is potential that certain biochars could be used to mitigate P losses effectively. As there is a large body of work involving biochars being carried out at present and there is the potential in their use for P remediation, the impact of the landspreading of biochar on GHG emissions was also evaluated as part of this study.

When evaluating the feasibility of any amendment to slurry, it is critical that whilst amendments may prevent nutrient loss in the solute phase, the ‘pollution swapping’, defined by Stevens and Quinton [30] as ‘the increase in one pollutant as a result of a measure introduced to reduce a different pollutant’ in the gaseous phase be considered. Therefore, the aims of this study were: (i) to elucidate the effects of chemical treatment on the loss of NH3, CH4, N2O, and CO2 from dairy cattle slurry applied to grassland soils and (ii) to further refine the feasibility of using chemical amendment based on their potential for greenhouse warming effects.

Materials and Methods

Soil sample collection and analysis

Intact soil samples were taken from a dairy farm (53°21'150 N, 8°34' W) in County Galway. No permission was required at either location as these were research dairy farms located at Teagasc, Athenry and the corresponding author and co-author (Owen Fenton) are both research officers in Teagasc. Aluminium (Al) coring rings, 120-mm-high, 100-mm-diameter, were used to collect undisturbed soil core samples (n = 18). Soil samples, taken to a depth of 100 mm below the ground surface from the same location, were air dried at 40°C for 72 h, crushed to pass a 2 mm sieve, and analysed for Morgan’s P (the national test used for the determination of plant available P in Ireland) using Morgan’s extracting solution [31]. Soil pH (n = 3) was determined using a pH probe and a 2:1 ratio of deionised water-to-soil. Soil texture was determined by particle size distribution [31]. Organic matter (OM) content of the soil was determined using the loss of ignition [32]. The soil was a poorly-drained sandy loam (58% sand, 27% silt, 15% clay) with a Morgan’s P of 22±3.9 mg P L-1, a pH of 7.45±0.15 and an OM content of 13±0.1%. Historic applications of organic P from an adjacent commercial sized piggery led to high STP in the soil used in this study.

Dairy slurry collection and analysis

Cattle slurry from dairy replacement heifers was taken from a dairy farm (53°21’ N, 8°34’ W) in County Galway, Republic of Ireland. No permission was required at either location as these were research dairy farms located at Teagasc, Athenry and the corresponding author and co-author (Owen Fenton) are both research officers in Teagasc. The field studies did not involve endangered or protected species. Before sample collection, the storage tanks were agitated. Samples were transported to the laboratory in 10-L drums and stored at 4°C. The pH of slurry and amended slurry was determined using a pH ProfiLine 3110 probe (WTW, Germany) and the water extractable phosphorus (WEP) of slurry was measured at the time of land application [33]. The total P (TP) of the dairy cattle slurry was determined after Byrne [33]. Potassium (K) and magnesium (Mg) were analyzed using a Varian Spectra 400 Atomic Absorption instrument and analyses for N and P were carried out colorimetrically using an automatic flow-through unit. Ammoniacal nitrogen (NH4-N) of slurry and amended slurry was extracted from fresh slurry by shaking 10g of slurry in 200 ml 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) on a peripheral shaker for 1 h and filtering through a No 2 Whatman filter paper and analysed using an Aquakem 600 Discrete Analyser (Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland).Total C and N content of slurry were analysed using a LECO TruSpec CN analyser (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA).

Chemical amendment of slurry

Six treatments were examined under laboratory conditions in this study, with treatments selected from Brennan et al. [23, 24]. With the exception of biochar, the amendments were applied at the following stoichiometric rates determined from Brennan et al. [24]: alum 1.11:1 (Al: TP); PAC 0.93:1 (Al:TP); FeCl2 2:1 (Fe:TP); and lime 10:1 (Ca: TP). Biochar, was derived from wood shavings (2 mm diameter) pyrolised in a muffle furnace at 650°C for 4.5 hours and was applied at a rate equivalent to 3.96 m3 ha-1. This rate was selected based on results of a batch experiment to reduce ammonia emissions (Brennan et al., unpublished data). Slurry characteristics for each amendment are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Dairy cattle slurry and amended dairy cattle slurry properties.

| Treatment | DM (%) | pH | WEP (g kg-1 DM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slurry only | 10.5 (0.04) | 7.5 (0.05) | 1.81 (0.112) |

| Alum | 9.4 (0.16) | 5.4 (0.12) | 0.008 (0.002) |

| Lime | 8.2 (0.29) | 12.2 (0.12) | 0.014 (0.001) |

| FeCl2 | 10.1 (0.22) | 6.7 (0.06) | 0.017 (0.001) |

| PAC | 9.6 (0.28) | 6.4 (0.05) | 0.011 (0.002) |

| Charcoal | 12.57 (0.45) | 7.3 (0.4) | 1.78 (0.23) |

The amendments were added to the slurry and mixed rapidly using a blender immediately before simulated land application. Slurry and amended slurry were applied directly to the surface of the intact grassed soil at a rate equivalent to 33 m3 slurry ha-1. Immediately after application, the chambers were sealed and the air flow through the system was started and maintained for 168 h.

Measurement of ammonia (NH3)

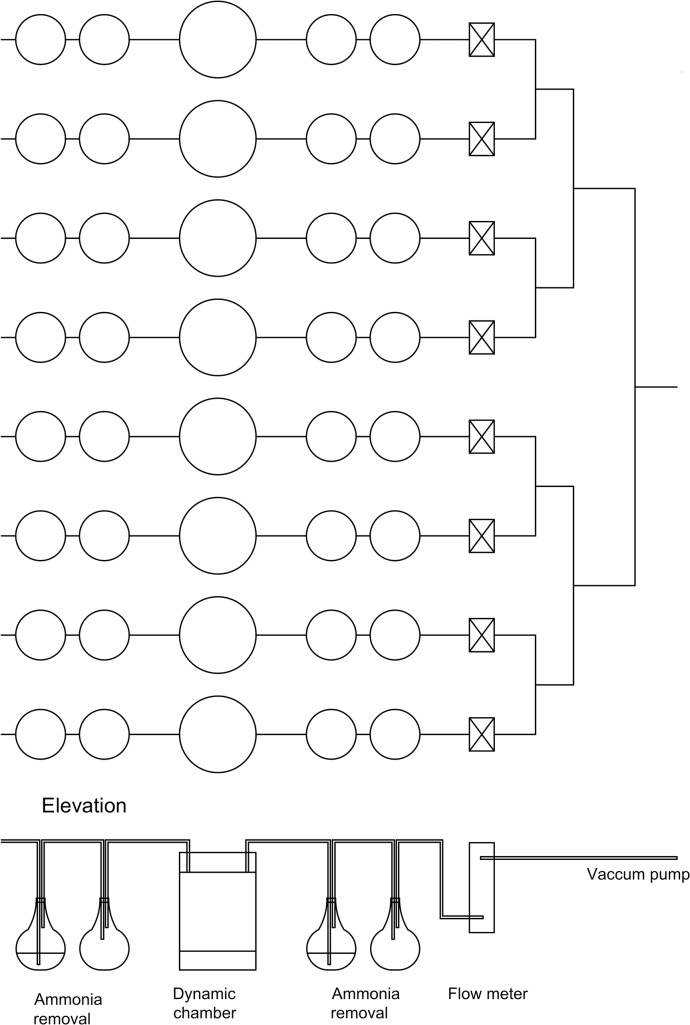

Soil chambers comprised the same 200-mm-diameter aluminium casings used to collect the grassed soil samples, fitted with a polypropylene (PP) lid and base (Figs 1 and 2). The samples were saturated for 48 h and then allowed to drain for 48 h under laboratory conditions. During this time, the surfaces were covered to avoid evaporation losses. After approximate field capacity was achieved, the chambers were sealed at the base using silicon grease to ensure an air-tight seal. Each treatment was applied to the grassed-soil surface and a lid was fitted to each chamber. Each chamber had four inlet and outlet ports to ensure good mixing of air within the chamber.

Fig 1. Diagram of apparatus.

Fig 2. Schematic of the dynamic chambers.

The dynamic chamber used in this experiment consisted of an open dynamic chamber system, with ammonia concentrations measured at the inlet and outlets to the chambers. Eight chambers per treatment were connected in parallel (Fig 1). Air was drawn through the system via a vacuum pump, (VTE 10 vacuum pump, Irish Pneumatic Service Ltd., Ireland) with air flow through each chamber regulated at 5.1 L min-1 using gas mass flow meters at the inlet and outlet (Cole-Parmer, Hanwell, UK).

The air flow regulation ensured that the emission of NH3 would not be affected by small differences in flow rates between chambers [32]. Ammonia contained in the air at both the inlets and outlets of the chambers was immobilised by acid trapping method. This involved bubbling the air through conical flasks containing 3% oxalic acid in an acetone solution.

The cores were attached to the dynamic chamber for 168 hours, with flasks replaced after 1, 2, 6, 24, 48, 96 and 168 hours The majority of NH3 volatilisation arising from spreading of slurry occurred in initial 48 h after spreading. Therefore, it was only necessary to use the acid-trap system for the first 168 h. Fluxes were subsequently calculated as the differential between the inlet and outlet NH3 concentration, accounting for the mass flow of air across the chamber per unit time [34].

Measurement of CH4, N2O and CO2

Methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2) were measured by re-configuring the chambers to a dynamic closed system. Air samples were drawn from the head space of the chamber and circulated into a photo-acoustic-analyser (PAA; INNOVA 1412, Lumasense Inc, Denmark) which analysed for CH4, CO2 and N2O. Water vapour was scrubbed prior to entering the analyser by placing a tube containing a mixture of magnesium perchlorate and glass beads in line at the outlet. This prevented water vapour interference within the portion of the infra-red spectrum where methane optimally absorbs (1254 cm-1). Subsequently the air was vented back into the chambers. Therefore, the flux could be calculated as the increase in gas concentration as a function of time. During the first 168 h (during which time NH3 was measured), each chamber was disconnected from the ammonia acid-trap apparatus, and the inlet and outlet tubes connected to the PAA in a closed circuit. Gas was circulated between the chamber and analyser for 10 min at t = -1 (1 hr before treatment), 0, 2, 6, 24, 48, 72, 96, 144, 168. Fluxes were calculated from the concentration increase of each gas over this period. After 168 h, NH3 measurement was discontinued and the chambers, containing intact soil samples, were removed from the apparatus and incubated in the laboratory. During this time, a portable cap was fitted to each chamber and the PAA was used to measure fluxes over a 15 minute period at t = 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17 d. The mass of the sample, and therefore water content, was kept constant throughout the experiment by periodically adding deionised water to the surface of the soil samples.

Pollution swapping and feasibility

All greenhouse gas emissions were converted to CO2 equivalents (IPCC, 2006). The ranking system, determined by Brennan et al. [23], was based on effectiveness of amendments, efficiency of amendments, cost of sourcing and addition of amendments to slurry and potential barriers to use. This study incorporated the greenhouse warming potential (GWP) of each of the amendments into this ranking system. The amendments were ranked from best to worst in decreasing order to enable a combined feasibility score to be calculated. In terms of ranking the pollution balances a weighting system can be applied, whereby the weighting of trade-offs between different loss pathways can be judged (Eq 1). The advantage of this is that different regions can apply different weightings depending on the environmental policy emphasis. An example here is where aeration is a problem in a system, resulting in a trade-off between CH4 and N2O or N2O and NH3. Ammonia was classified separately rather than expressing it in terms of an indirect greenhouse gas, due to the fact that it has multiple impacts.

| (1) |

where a-d and so on are weighting factors and B is the cumulative loss of a given pollutant over a pre-defined period (eg. one year). Other contaminants in gaseous (e.g. NH3 and H2S), dissolved (e.g. ammonium, metals) and particulate (e.g. particulate P) forms may also be added.

Statistical analysis

Data were checked for normality and homogeneneity of variance by histograms, qq plots, and formal statistical tests as part of PROC UNIVARIATE procedure of SAS [35]. The data were analysed using the PROC GLM procedure [35]. This analysis used a linear model which included the fixed effects of treatment. With the exception of slurry pH, NH3, CH4 and CO2, data were logarithmically transformed prior to analysis. A multiple comparisons procedure (Tukey) was used to compare means.

Results

Slurry and amended slurry results

The slurry had total N (TN) of 4430±271 mg L-1, total P of 1140±76 mg L-1, total K (TK) of 4480±218 mg L-1, and a pH of 7.5±0.05. The slurry TP and TK remained relatively constant, while the WEP was lowered significantly by all chemical amendments (Table 2). Alum, FeCl2 and PAC addition reduced slurry pH from approximately 7.5 to 5.4, 6.7, and 6.4, respectively (p<0.005). The pH of alum-amended slurry was significantly different to all other treatments, while FeCl2 and PAC were not significantly different to each other. Addition of lime increased slurry pH to 12.2 (p<0.001), while charcoal did not have a significant effect on slurry pH.

Table 2. Cumulative CH4, CO2, N2O and NH3 emissions from amended and control slurries for 15 days post-application.

| Treatment | CH4 (kg CH4-C ha-1) | CO2 (kg CO2-C ha-1) | N2O (kg N2O-N ha-1) | NH3 (kg NH3-N ha-1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | std | mean | std | mean | std | mean | std | |

| Slurry only | 8.45a | 8.29 | 440.4a | 11.2 | 0.39a | 0.13 | 28.5a | 2.52 |

| Alum | 7.62a | 2 | 526.5a | 6.2 | 1.18b | 0.78 | 2.46b | 2.01 |

| FeCl2 | -0.75b | 0.98 | 467.4a | 71 | 0.99b | 0.17 | 13.2a | 1.02 |

| Lime | -2.88b | 0.77 | 489.4a | 69.1 | 0.2a | 0.1 | 60.3a | 10.3 |

| PAC | -2.0 b | 0.29 | 457.3a | 66.6 | 0.3a | 0.08 | 1.07b | 3.19 |

| Biochar | 0.1 b | 0.2 | 72.7b | 44.1 | 0.1a | 0.02 | 7.36b | 3.38 |

Letters indicate least significant difference (P<0.05) between treatments.

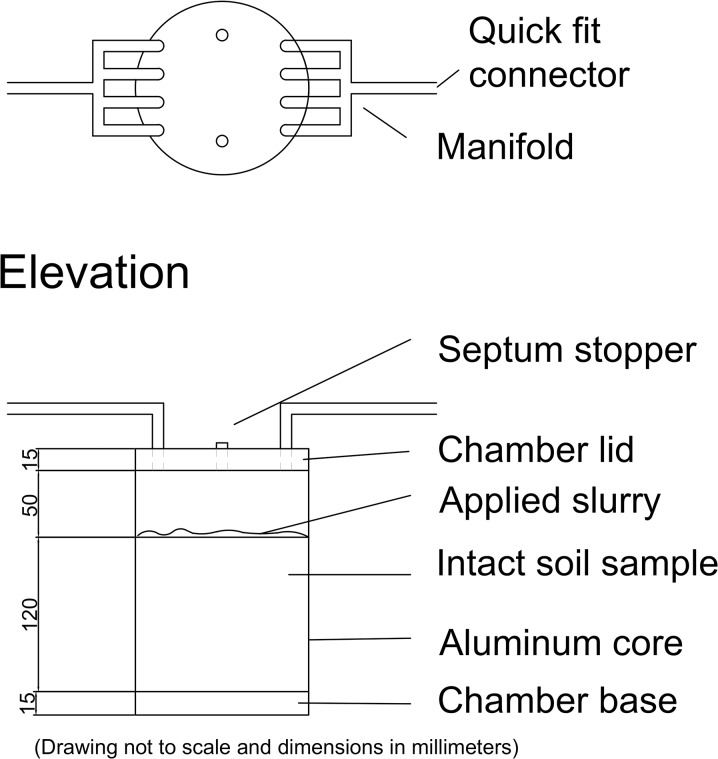

Ammonia

Alum), FeCl2 PAC and biochar significantly reduced NH3 emissions by 92, 54, 65 and 77% compared to the slurry control (p<0.01), while lime increased emissions by 114% (p<0.01, Table 2). Lime amendment resulted in the loss of 84% of TAN applied. Alum, PAC, FeCl2 and char were not statistically different to each other. The NH3 emissions from broadcast-applied untreated and chemically amended slurry, expressed as a percentage of TN and NH4-N in the applied slurry, are shown in Fig 3. Ammonia release from slurry for all treatments followed a Michaelis-Menten response curve, with the majority of emissions occurring within the first six hours following application. With the exception of the lime treatment, chemical amendment of slurry prior to land application increased the time for half of ammonia losses to occur (T0.5). Alum, FeCl2, PAC and biochar all increased T0.5 significantly (p<0.001) compared to the slurry control, from 1.5 to 4.1, 3.5, 4.3 and 3.4 h, respectively. The T0.5 of lime-amended slurry was not significantly different to the slurry control. Cumulative ammonia release from untreated slurry was 40% of TAN.

Fig 3. Ammonia emissions.

Emissions from untreated and chemically amended slurry expressed as a percentage of total nitrogen in slurry and total ammoniacal nitrogen in slurry.

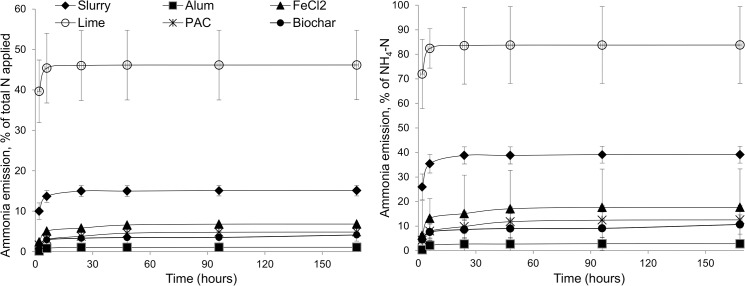

Nitrous oxide

Cumulative N2O emissions of dairy cattle slurry increased when amended with alum and FeCl2 by 202 and 154% respectively compared to the slurry control. In contrast, lime and biochar resulted in a reduction of 44%, and 63% in cumulative N2O loss compared to the slurry control while PAC did not have a significant effect on N2O emissions (Table 2). In this study, nitrous oxide emissions following land application of dairy cattle slurry were observed to increase from background levels of 0.18 g N2O-N ha-1 h-1 to a peak of 4 g N2O-N ha-1 h-1 at 24 h post-application (Fig 4). Emissions of N2O from alum were similar in magnitude and temporal dynamics to those from the slurry control. Ferric chloride addition resulted in no increase in N2O emissions until the 72 h sampling event, and a peak flux of 4.7 g N2O-N ha-1 h-1 was measured at 96 h. Lime, PAC and biochar addition resulted in much lower emissions, with peak emissions occurring after 24–48 h.

Fig 4. Nitrous oxide emissions profile.

Temporal profile of nitrous oxide (N2O-N) emissions from amended slurry and control treatments for 15 days after application.

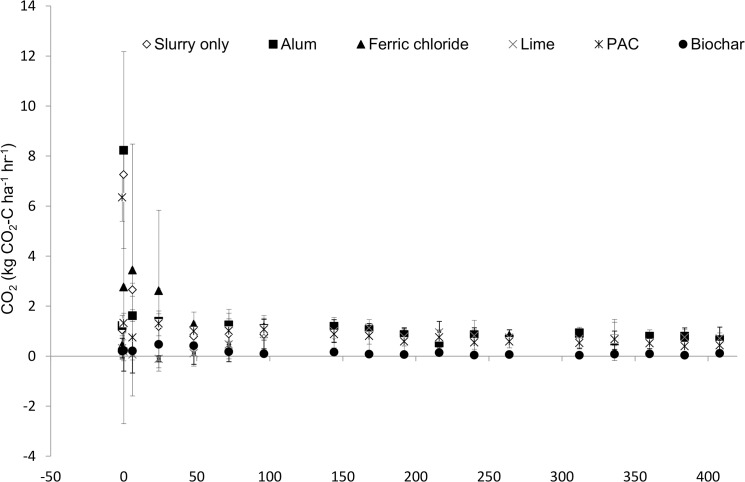

Carbon dioxide

In general, addition of amendments to slurry did not significantly affect soil CO2 release during the study (Fig 5), with cumulative emissions for the period ranging from 420–480 kg CO2 ha-1 (Table 2). However, significant reductions in CO2 efflux were observed upon biochar addition, with an 84% reduction in cumulative CO2 emissions observed (p<0.05). Immediately following land application of dairy cattle slurry and chemically amended slurry, there was generally a peak in CO2 emissions followed by a steady release for the duration of the study. The lime amended slurry behaved differently to the other treatments and the slurry control, and acted as a CO2 sink immediately after land application. However, the cumulative emissions were similar to PAC and FeCl2 treated slurry.

Fig 5. Carbon dioxide emissions profile.

Temporal profile of carbon dioxide (CO2-C) emissions from amended slurry and control treatments for 15 days after application.

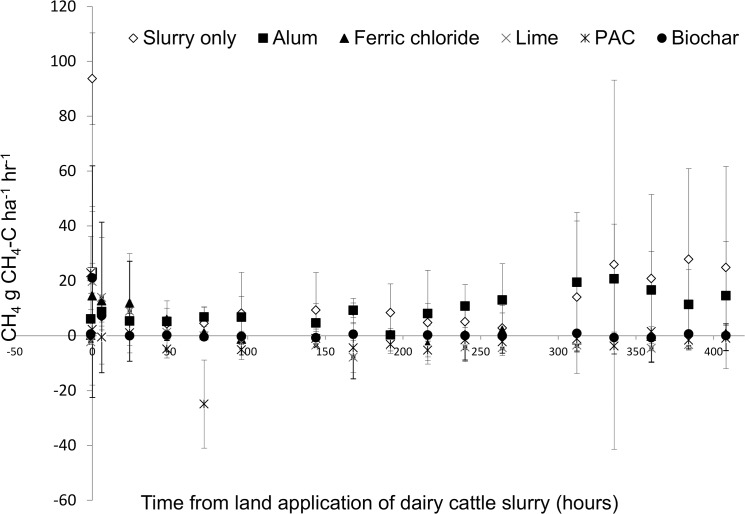

Methane

Methane emissions increased from -0.18 g CH4-C ha-1 h-1 to 94 g CH4-C ha-1 h-1 upon application of dairy cattle slurry (Fig 6). These levels decreased rapidly to approximately 7 g CH4-C ha-1 h-1 by 48 h and remained relatively constant until the 312 h sampling event. Following this, methane losses were much more variable. There was a similar trend for all of the amended slurries applied with an initial increase in losses followed by a rapid decrease and then steady release for the duration of the study. All of the amendments examined reduced the initial peak in CH4 emissions compared to the slurry control (p<0.05). Lime significantly reduced cumulative CH4 emissions by 134% (p<0.05, Table 2). PAC and FeCl2 (p<0.09) also reduced cumulative CH4 emissions compared to the slurry control by 121 and 99%, respectively. However, these reduction were not significant (p = 0.08 and p = 0.09 respectively). Alum, and biochar had no significant effect on emissions compared to the slurry control.

Fig 6. Methane emissions profile.

Temporal profile of methane (CH4-C) emissions from amended slurry and control treatments for 15 days after application.

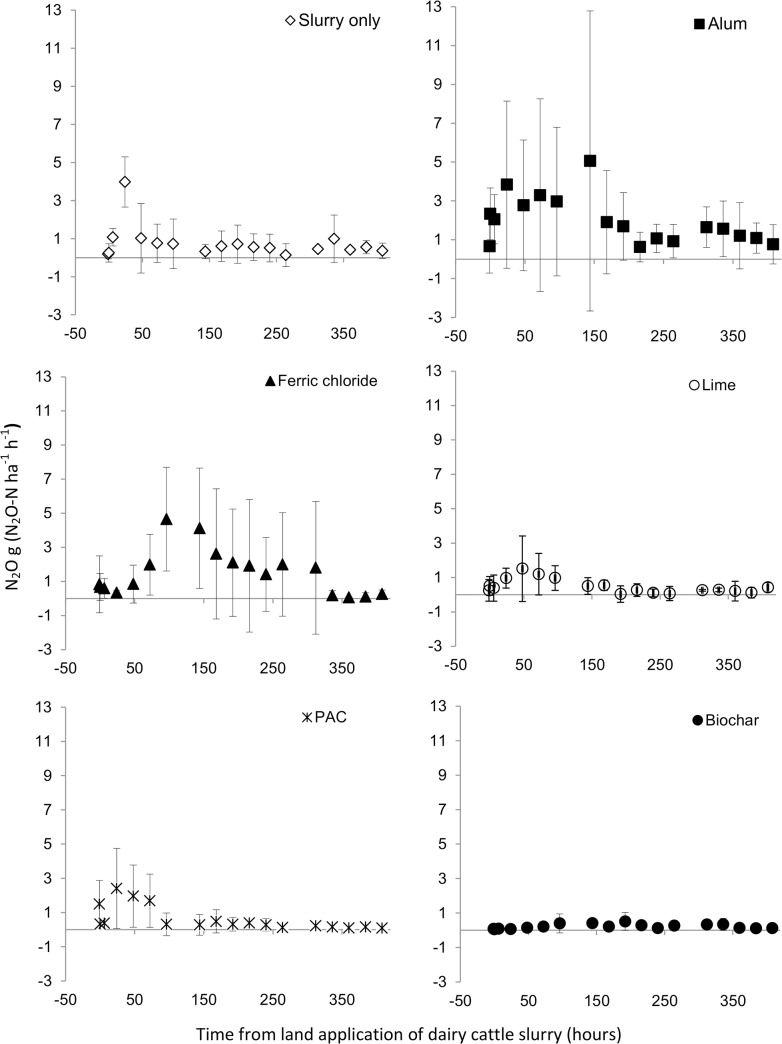

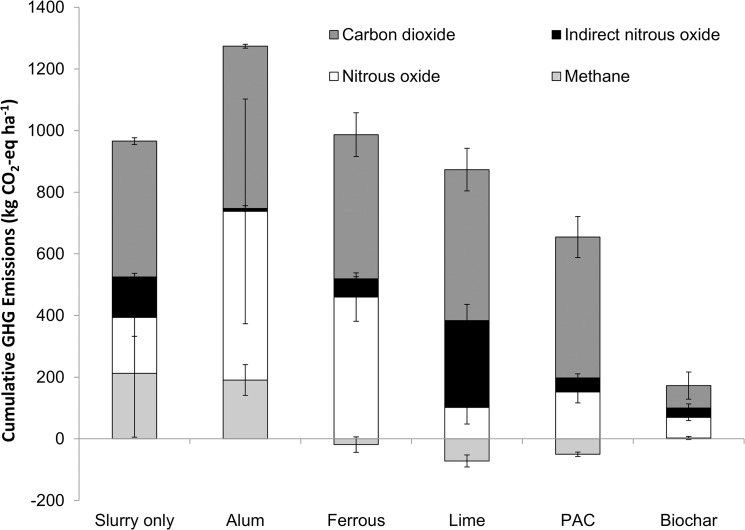

Impact of amendments on global warming potential

Chemical amendment of dairy cattle slurry has been proposed as a possible P mitigation measure for the control of P solubility in dairy cattle slurry [23, 24]. In order to access the pollution swapping potential of the treatments, all emissions were expressed in CO2 equivalents. Cumulative direct and indirect N2O emissions from slurry and amended slurry in the chambers during the study are shown in Fig 7. Indirect N2O emissions were calculated based on the assumption that all the NH3 would be re-deposited within a 2 km radius of the point of application, which allowed use of an emission factor of 1% [19]. Alum, FeCl2, lime and PAC have no significant effect on the sum of the cumulative direct and indirect N2O emissions, while charcoal reduced total N2O emissions by 69% compared to the slurry control (p<0.01). The total N2O emissions from charcoal treated slurry–with the exception of PAC—were statistically different to slurry (p<0.01), alum (p<0.01), FeCl2 (p<0.01), lime (p<0.01) treatments. Cumulative carbon dioxide and methane emissions are shown in Fig 7. Biochar reduced total cumulative CO2 and CH4 emissions compared to the control (p<0.01) and was significantly different (p<0.05) compared to alum, FeCl2), lime and PAC. Amendment of slurry with biochar significantly reduced GWP following land application of dairy cattle slurry (p<0.01). In this study, there was no significant effect of any amendment of slurry on GWP caused by land application dairy cattle slurry, with the exception of biochar.

Fig 7. Cumulative greenhouse gas emissions.

Total emissions (expressed as CO2- equivalents) for 15 days post-application of amended and control slurries.

Discussion

In general, P amendments affected gaseous emission by either altering slurry pH or increasing immobilisation. For instance, lime, PAC and biochar addition resulted in a reduction in N2O emissions, but while the reductions associated with PAC and biochar were most likely due to N immobilisation, the lack of N2O associated with lime application was due to increased ammonia loss. This demonstrated the need to quantify all loss pathways when evaluating amendments.

Ammonia emissions

Ammonia volatilisation from dairy cattle slurry following land application is influenced by humidity, temperature, wind speed, method of application, and the degree of infiltration of the slurry into the soil [7,8, 9, 36,37, 38]. In addition, slurry pH, DM and TAN content greatly influence the rate and amount of NH3 volatilisation [7, 8, 9 39]. It is estimated that between 60–80% of TAN applied can be lost during broadcast land spreading of cattle slurry, particularly during the first 12 h post application [22, 40]. In the present study, cumulative NH3 loss from land applied dairy cattle slurry was 22.6 kg NH3-N ha-1, with approximately 39% of NH4-N applied lost in initial 24 h; this was equivalent to 15% of total nitrogen (TN) applied.

With the exception of lime, all amendments used reduced NH3 losses compared to the slurry control. This reduction was expected as chemical amendments, such as alum, have been used extensively in the USA to reduce NH3 emissions from poultry litter [41] and from dairy cattle slurry (Table 3). A 60% reduction in NH3 loss from dairy cattle slurry was reported when 2.5% by weight of alum was added in a laboratory batch experiment [39], while in a field study, a 92% reduction in NH3 loss was observed in a field study where alum had been applied [42]. The results of the present study were in agreement with previous findings for alum, PAC and FeCl2, and the ammonia abatement by alum, PAC and FeCl2 was primarily due to reductions in pH (ie. N was held in the ammonium form).

Table 3. Summary of amendments used to reduce ammonia emissions in previous studies.

| Reference | Chemical | Amount added | Slurry type | Study | %reduction | pH | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meisinger et al. (2001) | alum | 2.5% (w/w) | Dairy | Lab | 60 | 4.5 | Simulated storage experiment |

| zeolite | 6.25% (w) | 55 | 7.8 | ||||

| Kai et al. (2007) | H2SO4 | 5 kg m-3 | Swine | Field | 70 | 6.3 | Farm scale storage and application |

| Smith et al. (2001) | Alum | 0.75% (v/v) | Swine | Plot | 52 | 6-week study | |

| Molloy and Tunney (1983) | FeSO4 | 0.8 g to 25 g | Dairy | Batch | 81 | Batch scale experiment | |

| MgCl2 | 0.8 g to 25 g | 23 | |||||

| CaCl2 | 0.8 g to 25 g | 50 | 7.8 | ||||

| Shi et al. (2001) | Alum | 4500 kg/ha | Dairy | Field | 92 | 5.98* | Applied to surface of feedlot |

| CaCl2 | 4500 kg/ha | 71 | 6.99* | ||||

| Husted et al. (1991) | HCL | 240 mEq | Dairy | 90 | |||

| CaCl2 | 300 mEq | Lab | 15 |

*pH mentioned here is pH of soil and slurry mixture.

The large reductions in ammonia emissions associated with biochar addition (74%) may have been due to both ammonia gas and ammonium ion adsorption, as biochar can act as a cation exchange medium [43]. During pyrolysis of woody material for biochar production, thermolysis of lignin and cellulose occurs, exposing acidic functional groups, such as carboxyl groups. This has been shown to result in an 80% 100% removal efficiency for ammonia gas [44, 45]. Biochar addition during the composting of poultry litter reduced ammonia losses by 64%, even though pH increased [46]. As a result, the mechanism was thought to be due to the adsorption of ammonium ions as opposed to the immobilization of ammonia [47]. In addition, biochar has also been found to reduce N leaching by 15% due to adsorption of the ammonium ion predominantly by cation exchange [48].

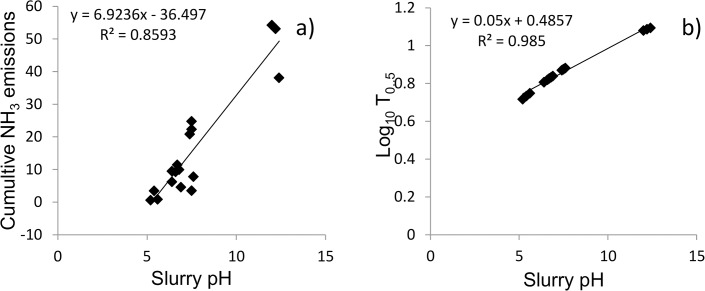

Lime increased slurry pH to 12.2 and increased the NH3 loss compared to the slurry control. Indeed, modeled results have estimated that NH3 emissions increase by 3.3 kg ha-1 for each increment of 0.1 pH [49]. There was a linear relationship between slurry pH at time of application and NH3 loss from slurry and amended slurry in this study (R2 = 0.86) (Fig 8). This would indicate that the change in slurry pH was the main process responsible for the reduction in NH3 loss from dairy cattle slurry. In addition, there was a significant relationship (R2 = 0.98) between slurry pH at time of application and the log of the T0.5 (Fig 8). This would indicate that if large NH3 losses do not occur in the short term after land spreading, the potential for loss is significantly reduced i.e. chemical treatments are not just delaying NH3 loss, but mitigating it completely.

Fig 8. Correlation between ammonia and time.

Relationship between slurry and amended slurry pH at time of application and (a) cumulative NH3 emissions and (b) and log of time for half of ammonia emissions to occur (T0.5).

In addition to environmental problems caused by NH3 losses, such losses reduce the nutrient value of the fertiliser and increase NH3 emissions from slurry. The value of N lost via ammonia and N2O emissions from the slurry control for the duration of the study amounted to approximately €0.63 per m3 slurry applied based on cost of €1.10 per kg N [50]. Alum, FeCl2, PAC and biochar increased the fertiliser value of slurry by €0.56, €0.32, €0.41 and €0.48 per m3 slurry compared to the slurry control.

Nitrous oxide

Land application of agricultural wastes results in an increase in N2O emissions from soil) and these emissions are influenced by: soil moisture status, soil temperature; soil nitrate (NO3) content and organic carbon content [51, 52]. It was hypothesised that any reduction in NH3 loss would result in a concomitant increase in soil–derived N2O due to higher mineral N available for nitrification/denitrification. Whilst there were no significant differences due to large standard deviations within treatments, this general trend was observed for both alum and ferrous chloride treatments where large reductions in ammonia emissions were offset by a doubling in cumulative N2O losses compared to the slurry only treatment. Also, whilst lime addition resulted in a decrease in direct N2O losses, these were merely due to the fact that most of the available mineral N had been already lost during volatilisation. Indeed, only biochar addition significantly lowered emissions (p<0.01) relative to the slurry control. Ammonia volatilisation can also lead to indirect N2O emissions as the majority of ammonia volatilised in the field is re-deposited within 2–5 km via wet and dry deposition, and a proportion (1%) is re-emitted as N2O [19]. When these indirect losses were calculated, lime addition accounted for an increase in indirect N2O emissions from 283 g N2O ha-1 for the slurry control to 606 g N2O ha-1. These results highlight the need to account for all gaseous N losses as an analysis of ammonia or N2O in isolation would give skewed results.

In terms of abating total N emissions, char was the most effective with losses reduced by 63%. Other studies comparing biochar and hydrochar effects on soil GHG emissions have observed a 40–50% reduction in N2O release [27, 28]. However, this abatement potential is highly dependent on the source material of the char and the temperature of pyrolization [28, 53]. The rate of char application may be less important, with studies comparing 1% and 3% biochar incorporation reporting similar levels (50%) of emission reduction [28]. The mechanism for N2O reduction is unclear. Some studies have indicated that biochar may reduce N2O by increasing soil aeration and hence reduce water-filled pore space [54]. Also adsorption of ammonium (NH4 +) or nitrate (NO3 -) onto the charcoal surface has been hypothesised [44]. Alternatively, if pH is increased upon char addition, this may induce a shift towards total de-nitrification to N2, thus reducing N2O [55].

Carbon emissions

There was no significant change soil CO2 respiration upon amendment addition, with the exception of biochar, where a significant reduction in CO2 emissions was observed. Previous reported effects of char application on CO2 efflux are varied. Biochar application to organic manures has shown an increase in C emissions in the short term [46], while biochar addition to soils have also indicated a simulation of soil microbial respiration [56]. A comparison on the effect of 16 biochars on CO2 emissions reported increases and decreases in emissions, depending both feedstock, method and temperature of pyrolysis [53]. Similarly, a 90% reduction in soil respiration was observed upon the addition of wood-derived char to soil whilst the addition of hydrochars stimulated CO2 release [27]. The differences between previous reports are possibly due to variations in the proportion of labile C available on the char and the mineralization of carbonate groups on the surface of the biochar. Suppression of soil respiration upon char addition is most likely, therefore associated with either sorption of CO2 onto the biochar or a reduction in labile C availability.

After land application, CH4 emissions are of minor importance compared to NH3 and N2O emissions [57]. Methane is produced mainly by microbial decomposition of organic matter under anaerobic conditions. The highest efflux was for untreated slurry and alum, immediately post manure application would indicate CH4 formation during manure storage, as there would not be sufficient time for its formation in the soil. It is produced during slurry storage and shortly after slurry application, after which time the organic matter is oxidised to CO2 and H2O as aerobic conditions prevail. Initial CH4 emissions in the following few hours most likely originate from CH4 contained in the manure diffusing from the viscous layer, while subsequent emissions were likely to be produced during the degradation of labile C compounds [58 59]. Similar base-line CH4 soil emission levels of 1.1 kg CH4-C ha-1 day-1 (3.01 g CH4-C ha-1 day-1) have been observed from Swedish cereal cropped soils [60, 61] reported, while similar peaks CH4 emissions of approximately 75 g CH4-C ha-1 day-1 immediately post application of cattle slurry to grassland have been recorded [58]. High emission levels following pig and dairy manure application to grassland soil in laboratory experiments have also been reported [15].

Biochar suppressed CH4 emissions upon slurry landspreading. Amendment of biochar to wastewater sludge has previously been shown to have no effect on methane release [28] and indeed biochar addition to soils have been shown to reduce oxidation of methane [27]. However, this may be soil-specific with highly organic soils that are prone to methane emissions, exhibiting a decrease in emissions [51]. In general, the effect of biochar on methane release and/or uptake appears to be variable.

Impacts of pollution swapping

Whilst the efficacy of the various slurry amendments on P sequestration efficiency is well quantified [23, 24, 62, 63], there is less information on their effects on other loss pathways, particularly gaseous emissions. This study gives a much needed consideration to the risk of amendments on gaseous losses which are critical in selecting amendments for recommendation to legislators. The study also allowed for the effect of chemical amendment on gaseous emissions to be incorporated into the feasibility analysis of Brennan et al. [23]. A new feasibility analysis was developed to include the results of this study and to give recommendations for the best amendment to mitigate DRP losses with the least potential for pollution swapping. The results of this feasibility analysis are shown in Table 4. Biochar was excluded as there is insufficient data on P sequestration potential to date. In order of decreasing feasibility, the amendments were ranked from best to worst as follows: PAC, alum, FeCl2 and lime. Therefore, the amendments selected for recommendation for further study are from best to worst: PAC, alum and lime. Ferric chloride was excluded due to risk of stability of Fe-P bonds in soil. Although there are similar concerns with lime, it is currently added to soil in Ireland to reduce acidity in soils and for this reason, it was decided to recommend lime over FeCl2.

Table 4. Summary of feasibility of amendments (Adapted from Brennan et al. (2011)).

| Chemical | Ratio used Brennan et al. (2011a) | Feasibility score P | Pollution swapping score | Feasibility score | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alum | 0.98:1 Al: P | 1 | 5 | 6 | Risk of effervescence | |

| Risk of release of H2S due to anaerobic conditions and reduced pH | ||||||

| Cheap and used widely in water treatment | ||||||

| Reduced ammonia emissions | ||||||

| PAC | 0.98:1 Al: P | 2 | 2 | 4 | No risk of effervescence (Smith et al., 2004) | |

| AlCl3 increased handling difficulty | ||||||

| Expensive | ||||||

| Reduced ammonia emissions | ||||||

| FeCl2 | 2:1 Fe: P | 3 | 4 | 7 | Potential for Fe bonds to break down in anaerobic conditions | |

| Increased release of N2O | ||||||

| Reduced ammonia emissions | ||||||

| Ca(OH)2 | 5:1 Ca: P | 4 | 3 | 7 | Increased NH3 loss | |

| Strong odour | ||||||

| Hazardous substance | ||||||

| Biochar | 1 | Potential to reduce P solubility limited work to date | ||||

| Improve soil microbial health | ||||||

| Reduced GHG emissions | ||||||

| Reduced ammonia emissions | ||||||

Marks for feasibility and pollution swapping are from 1 to 5. 1 = best 5 = worst.

Conclusion

This study has shown that some P mitigating amendments (Alum, FeCl2 and Lime) may result in pollution swapping in terms of gaseous emissions, whilst PAC may be effective in terms of abating both P and gaseous N losses. It also highlights the need to assess the trade-offs on a suite of emissions, particularly NH3 and N2O. In addition, there is a need to examine the effect of amendments using different soil types under different climatic conditions. This study has also shown that biochar has excellent potential to reduce total gaseous losses arising from land application of dairy cattle slurry. There is a need to develop biochars which are efficient in sorbing P and can improve soil quality and reduce GHG emissions. In addition, at the current cost of treatment, the increase in fertiliser value of the slurry due to some treatments is not sufficient to offset the cost of treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors are also grateful for assistance provided by Teagasc and NUI Galway staff and colleagues with special mention to Stan Lalor, Peter Fahy, Gerry Hynes, Maria Radford and Denis Brennan. The authors are also grateful to the reviewers who have improved the document.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Teagasc Walsh Fellowship Scheme and the AnimalChange Framework 7 Project (FP7-KBBE-2010-4). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Buda AR, Kleinman PJ, Bryant RB, Feyereisen GW. Effects of hydrology and field management on phosphorus transport in surface runoff. J. Environ. Qual. 2009; 38: 2273–2284. 10.2134/jeq2008.0501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carpenter SR, Caraco NF, Correll DL, Howarth W, Sharpley AN, Smith VH. Nonpoint pollution of surface waters with phosphorous and nitrogen. Ecol. Appl. 1998; 8: 559–568 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schulte RPO, Melland AR, Fenton O, Herlihy M, Richards KG, Jordan P. Modelling soil phosphorus decline: Expectations of Water Frame Work Directive policies. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2010; 13: 472–484 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Correll DL. The Role of Phosphorus in the Eutrophication of Receiving Waters: A Review. J. Environ. Qual. 1998; 27: 261–266 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stark CH, Richards KG. The continuing challenge of agricultural nitrogen loss to the environment in the context of global change and advancing research. Dyn. Soil Dyn. Plant 2008; 2: 1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vitousek PM, Naylor R, Crews T, David MB, Drinkwater LE, et al. Nutrient Imbalances in Agricultural Development. Science 2009; 324: 1519–1520 10.1126/science.1170261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith E, Gordon R, Bourque C, Campbell A, Genermont S, Rochette P, et al. Simulated management effects on ammonia emissions from field applied manure. J. Environ. Manage. 2009; 90: 2531–2536 10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Misselbrook TH, Van Der Weerden TJ, Pain BF, Jarvis SC, Chambers BJ, Smith KA, et al. Ammonia emission factors for UK agriculture. Atmos. Environ. 2000; 34: 871–880 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Misselbrook TH, Smith KA, Johnson RA, Pain BF Slurry. Application Techniques to reduce Ammonia Emissions: Results of some UK Field-scale Experiments. Biosyst. Eng. 2002; 81: 313–321 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amon B, Kryvoruchko V, Amon T, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S. Methane, nitrous oxide and ammonia emissions during storage and after application of dairy cattle slurry and influence of slurry treatment. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006;112: 153–162 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ellis S, Yamulki S, Dixon E, Harrison R, Jarvis SC. Denitrification and N2O emissions from a UK pasture soil following the early spring application of cattle slurry and mineral fertiliser. Plant Soil; 202: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meade G, Pierce K, O’Doherty JV, Mueller C, Lanigan G, et al. Ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions following land application of high and low nitrogen pig manures to winter wheat at three growth stages. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010; 140: 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bol R, Kandeler E, Amelung W, Glaser B, Marx MC, Preedy N. Short-term effects of dairy slurry amendment on carbon sequestration and enzyme activities in a temperate grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003; 35: 1411–1421. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bourdin F, Sakrabani R, Kibblewhite MG, Lanigan GJ. Effect of slurry dry matter content, application technique and timing on emissions of ammonia and greenhouse gas from cattle slurry applied to grassland soils in Ireland. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014; 188: 122–133 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chadwick D, Pain BF. Methane fluxes following slurry applications to grassland soils: laboratory experiments. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 197; 63: 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duffy P, Connolly N, Black K, O’Brien P. Ireland National Inventory Report 2011. 2012; EPA, Wexford, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- 17.EPA. Enviromental Protection Agency Trends in NH3 emissions 2008. Available: http://www.epa.ie/environment/air/emissions/ammonia/. Enviromental Protection Agency, 2010; Wexford, Ireland.

- 18. Crutzen PJ. Atmospheric chemical processes of the oxides of nitrogen, including nitrous oxide In: Delwiche CC, editor. Denitrification, Nitrification and Atmospheric Nitrous Oxide. New York: Wiley; 1981. pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories In: Eggleston H, Buendia L, Miwa K, Ngara T, Tanabe K, editors. The National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2006. IGES, Japan: [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goulding KWT, Bailey NJ, Bradbury NJ, Hargreaves P, Howe M, et al. Nitrogen deposition and its contribution to nitrogen cycling and associated soil processes. New Phytol. 1998; 139: 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferm M. Atmospheric ammonia and ammonium transport in Europe and critical loads: a review. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 1998; 51: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hyde BP, Carton OT, O'Toole P, Misselbrook TH. A new inventory of ammonia emissions from Irish agriculture. Atmos. Environ. 2003; 37: 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brennan RB, Fenton O, Grant J, Healy MG. Impact of chemical amendment of dairy cattle slurry on phosphorus, suspended sediment and metal loss to runoff from a grassland soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2011a; 409 (23): 5111–8 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brennan RB, Fenton O, Rodgers M, Healy MG. Evaluation of chemical amendments to control phosphorus losses from dairy slurry Soil Use Manage. 2011b; 27: 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lehmann J, Pereira da Silva J, Steiner C, Nehls T, Zech W, et al. Nutrient availability and leaching in an archaeological Anthrosol and a Ferralsol of the Central Amazon basin: fertilizer, manure and charcoal amendments. Plant Soil 2003; 249: 343–357. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Steiner C, Teixeira WG, Lehmann J, Nehls T, de Macêdo JLV, Blum WEH, et al. Long term effects of manure charcoal and mineral fertilization on crop production and fertility on a highly weathered Central Amazonian upland soil. Plant Soil 2007; 291: 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kammann C, Ratering S, Eckhard C, Muller C. Biochar and hydrochar effects on greenhouse gas (carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane) fluxes from soils. J. Environ. Qual. 2012; 41 (4):1052–66. 10.2134/jeq2011.0132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruun EW, Müller-Stöver D, Ambus P, Hauggaard-Nielsen H. Application of biochar to soil and N2O emissions: potential effects of blending fast-pyrolysis biochar with anaerobically digested slurry. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2011; 62: 581–589. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streubel J, Collins H, Granatstein D, Krugerand C. Biochar Sorption of Phosphorus From Dairy Manure Lagoons. In: Ippolito J, editor. ASA. CSSA, and SSSA 2010 International annual meetings. Biochar Effects On the Environment and Agricultural Productivity: I, 2010 Long Beach, CA

- 30. Stevens CJ, Quinton JN. Policy implications of pollution swapping. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C. 2009; 34: 589–594. [Google Scholar]

- 31.British Standards. British standard methods of test for soils for civil engineering purposes. Determination of particle size distribution. BSI; 1990. p. 2. BS 1377, London.

- 32.British Standards Determination by mass-loss on ignition. British standard methods of test for soils for civil engineering purposes. Chemical and electro-chemical tests. British Standards Institution,1990 p3 London.

- 33. Byrne E. Chemical analysis of agricultural materials–methods used at Johnstown Castle Research Centre, Wexford An Foras Taluntais, 1979, Johnstown Castle, Wexford. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kissel DE, Brewer HL, Arkin GF. Design and test of a field sampler for ammonia volatilisation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J; 1977; 41: 1133–1138. [Google Scholar]

- 35. SAS. SAS for windows. Version 9.1 SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Cary, NC.: SAS Institute Inc., 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Søgaard HT, Sommer SG, Hutchings NJ, Huijsmans JFM, Bussink DW, Nicholson F. Ammonia volatilization from field-applied animal slurry—the ALFAM model. Atmos. Environ. 2002; 36: 3309–3319. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sommer SG, Génermont S, Cellier P, Hutchings NJ, Olesen JE, Morvan T. Processes controlling ammonia emission from livestock slurry in the field. Eur. J. Agron. 2003;19: 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sommer SG, Jensen LS, Clausen SB, Sogaard HT. Ammonia volatilization from surface-applied livestock slurry as affected by slurry composition and slurry infiltration depth. J. Agr. Sci. 2006; 144: 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meisinger JJ, Lefcourt AM, Van Kessel J, Ann S, Wilkerson V. Managing ammonia emissions from dairy cows by amending slurry with Alum or Zeolite or by diet modification. Sci. World 2001; 1: 860–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pain BF, Phillips VR, Clarkson CR, Klarenbeek JV. Loss of nitrogen through ammonia volatilisation during and following the application of pig or cattle manure to grassland. J. Sc. Food Agric. 1989; 47: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moore PA Jr, Daniel TC, Edwards DR. Reducing phosphorus runoff and improving poultry production with alum. Poultry Sci. 1998; 78: 692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi Y, Parker DB, Cole NA, Auvermann BW, Mehlhorn JE. Surface amendments to minimise ammonia emissions from beef cattle feedlots. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2001; 44: 677–682. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Asada T, Ishihara S, Yamane T, Toba A, Yamada A, et al. Science of Bamboo Charcoal: Study on Carbonizing Temperature of Bamboo Charcoal and Removal Capability of Harmful Gases. J. Health Sci., 2002; 48: 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oya A, Iu WG. Deodorization performance of charcoal particles loaded with orthophosphoric acid against ammonia and trimethylamine. Carbon 2002; 40, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Iyobe T, Asada T, Kawata K, Oikawa K. Comparison of removal efficiencies for ammonia and amine gases between woody charcoal and activated carbon, J. Health Sci. 2004; 50: 148–153 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Steiner C, Das KC, Melear N, Lakly D. Reducing Nitrogen Loss during Poultry Litter Composting Using Biochar. J. Environ. Qual. 2009; 39: 1236–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Steiner C, Glaser B, Geraldes Teixeira W, Lehmann J, Blum WEH, et al. Nitrogen retention and plant uptake on a highly weathered central Amazonian Ferralsol amended with compost and charcoal. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2008; 2008; 171: 893–899. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ding Y, Liu YX, Wu WX, Shi DZ, Yang M, et al. Evaluation of Biochar Effects on Nitrogen Retention and Leaching in Multi-Layered Soil Columns Water Air Soil Pollut. 2010; 213:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith KA, Jackson DR, Misselbrook TH, Pain BF, Johnson RA. PA. Precision Agriculture: Reduction of Ammonia Emission by Slurry Application Techniques. J. Agr.l Eng. Res. 2000; 77: 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lalor S. Costs of adoption of low ammonia emission slurry application methods on grassland in Ireland In: Reis S., Sutton M.A., Howard C. (Eds.) Costs of ammonia abatement and the climate co-benefits. 2012; Springer Publishers; [Google Scholar]

- 51. Velthof G, Oenema O. Nitrous oxide emission from dairy farming systems in the Netherlands. Netherlands J. Agr. Sci. 1997; 45: 347–360. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Velthof G, Kuikman P, Oenema O. Nitrous oxide emission from soils amended with crop residues. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 2002; 62: 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Spokas KA, Reicosky DC. Impact of sixteen diff erent biochars on soil greenhouse gas production. Ann. Environ. Sci. 2009; 3:179–193. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yanai Y, Toyota K, Okazaki M. Effects of charcoal addition on N2O emissions from soil resulting from rewetting air-dried soil in short-term laboratory experiments. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2007; 53: 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Clough TJ, Condron LM. Biochar and the Nitrogen Cycle: Introduction. J. Environ. Qual. 2010; 39: 1218–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wardle DA, Nilsson MC, Zackrisson O. Fire-derived charcoal causes loss of forest humus. Science 2008; 320: 629 10.1126/science.1154960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wulf S, Maeting M, Clemens J. Application technique and slurry co-fermentation effects on ammonia, nitrous oxide, and methane emissions after spreading: II. Greenhouse Gas Emissions. J. Environ. Qual. 2002; 31: 1795–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chadwick DR, Pain BF, Brookman SKE. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions following application of animal manures to grassland. J. Environ. Qual. 2000; 29: 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sherlock RR, Sommer SG, Khan RZ, Wood CW, Guertal EA, et al. Ammonia, methane and nitrous oxide emissions from pig slurry applied to a pasture in New Zealand. J. Environ. Qual. 2002; 3:1491–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kasimir Klemedtsson Å, Klemedtsson L, Berglund K, Martikainen P, Silvola J, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from farmed organic soils: a review. Soil Use Manage. 1997;13: 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rodhe L, Pell M, Yamulki S. Nitrous oxide, methane and ammonia emissions following slurry spreading on grassland. Soil Use Manage. 2006; 22: 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dao TH. Co-amendments to modify phosphorus extractibility and nitrogen/phosphorus ration in feedlot manure and composted manure. J. Environ. Qual. 1999; 28: 1114–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dao TH, Daniel TC. Particulate and dissolved phosphorus chemical separation and phosphorus release from treated dairy manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2002; 31: 1388–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]