In contrast to previous results in the lung, skin-specific deletion of the Sag-βTrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase significantly accelerates mutant KrasG12D-induced skin papillomagenesis due to accumulation of Erbin and Nrf2, two novel Sag substrates, which blocks ROS generation and promotes proliferation.

Abstract

SAG/RBX2 is the RING (really interesting new gene) component of Cullin-RING ligase, which is required for its activity. An organ-specific role of SAG in tumorigenesis is unknown. We recently showed that Sag/Rbx2, upon lung-targeted deletion, suppressed KrasG12D-induced tumorigenesis via inactivating NF-κB and mammalian target of rapamycin pathways. In contrast, we report here that, upon skin-targeted deletion, Sag significantly accelerated KrasG12D-induced papillomagenesis. In KrasG12D-expressing primary keratinocytes, Sag deletion promotes proliferation by inhibiting autophagy and senescence, by inactivating the Ras–Erk pathway, and by blocking reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. This is achieved by accumulation of Erbin to block Ras activation of Raf and Nrf2 to scavenge ROS and can be rescued by knockdown of Nrf2 or Erbin. Simultaneous one-allele deletion of the Erbin-encoding gene Erbb2ip partially rescued the phenotypes. Finally, we characterized Erbin as a novel substrate of SAG-βTrCP E3 ligase. By degrading Erbin and Nrf2, Sag activates the Ras–Raf pathway and causes ROS accumulation to trigger autophagy and senescence, eventually delaying KrasG12D-induced papillomagenesis and thus acting as a skin-specific tumor suppressor.

Introduction

Ubiquitin serves as a molecular tag that marks proteins in most cases for targeted degradation. Ubiquitin labels proteins by three sequential enzymatic reactions comprising E1, ubiquitin-activating enzyme, E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and E3, ubiquitin ligase. The human genome encodes two E1s, at least 38 E2s, and >600 E3s (Ye and Rape, 2009). SCF (SKP1, Cullins, and F-box proteins) E3 ligase, also known as CRL1 (Cullin-RING ligase-1), the founding member of Cullin-RING ligases, is the largest family of E3 ubiquitin ligases, consisting of four components: (1) an adaptor protein SKP1, (2) a scaffold protein cullin-1 (CUL1), (3) a substrate-recognizing F-box protein, and (4) a RING (really interesting new gene) protein with two family members, RBX1 and RBX2 (also known as SAG). By promoting ubiquitylation and degradation of many key regulatory proteins, SCF E3s play the critical roles in many biological processes, including signal transduction, cell cycle progression, DNA replication, development, and tumorigenesis, among others (Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006; Deshaies and Joazeiro, 2009). Aberrant regulation of SCF E3s is involved in a broad range of cancers, including skin cancer (Jia and Sun, 2011; Xie et al., 2013b).

Of the two RING components of SCF, RBX1 (also known as ROC1) is constitutively expressed and preferentially bound to CUL1–4, whereas SAG/RBX2 is stress inducible with preferential association with CUL5 (Kamura et al., 2004) as well as CUL1 (Tan et al., 2011b). Both proteins are evolutionarily conserved (Sun et al., 2001; Wei and Sun, 2010) and are functionally nonredundant during mouse embryonic development (Tan et al., 2009, 2011b), although they are biochemically interchangeable in carrying out E3 ligase reactions (Swaroop et al., 2000). Our previous work showed that SAG regulated cell proliferation (Duan et al., 2001), apoptosis (Duan et al., 1999; Tan et al., 2011a), vasculogenesis and angiogenesis (Tan et al., 2011b, 2014), and tumorigenesis (Gu et al., 2007a; Li et al., 2014) by targeting the degradation of IκBα (Gu et al., 2007a; Tan et al., 2010), c-Jun (Gu et al., 2007a,b), pro-caspase-3 (Tan et al., 2006), HIF-1α (Tan et al., 2008), NF-1 (Tan et al., 2011b), p27 (He et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2014), and DEPTOR (Li et al., 2014).

Skin cancer is a common human cancer with >1 million new cases yearly in the United States (Einspahr et al., 2003). Mutational activation of Ras is found in 10–30% of human skin cancer (Spencer et al., 1995; Lapouge et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2013b). Using both in vitro and in vivo skin models, we previously demonstrated that Sag regulated epidermal transformation and skin tumorigenesis in a substrate-dependent manner. In a mouse JB6 epidermal culture model, SAG ectopic expression inhibited TPA-induced neoplastic progression via targeted degradation of c-Jun, leading to AP-1 inactivation (Gu et al., 2007b). In an in vivo 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene-12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (DMBA-TPA) two-step skin carcinogenesis model, in which H-ras mutation is involved (Balmain and Pragnell, 1983), SAG transgenic expression caused an early stage suppression of hyperplasia and tumor formation by promoting c-Jun degradation, thereby inhibiting AP-1, but a later-stage enhancement of tumor growth by promoting IκBα degradation, activating NF-κB and inhibiting apoptosis (Gu et al., 2007a). These stage-dependent SAG effects led to fewer numbers but a bigger size of tumors per animal in SAG transgenic mice compared with nontransgenic littermates (Gu et al., 2007a). We also found that in the same SAG transgenic model, UV exposure caused skin hyperplasia likely as a result of Sag-mediated degradation of p27 (He et al., 2008). However, it is totally unknown whether skin-targeted Sag loss has any effect in KrasG12D-triggered skin tumorigenesis and, if so, what is the underlying mechanism.

Erbb2-interacting protein (ERBB2IP), also known as Erbin, was first described in 2000, acting as an adaptor for the receptor ERBB2/HER2 in epithelia (Borg et al., 2000). Erbin belongs to the PDZ (PSD-95/DLG/ZO-1) protein family with 16 leucine-rich repeats in its amino terminus and a PDZ domain at its carboxyl terminus (Borg et al., 2000). Through its carboxyl-terminal PDZ domain, Erbin regulates the function and localization of ERBB2, also known as Her2/Neu, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is often associated with epidermal oncogenesis. Through its amino-terminal region, Erbin disrupts Ras–Raf interaction by preventing the Ras-binding protein Shoc2 from binding to Ras, and thus acting as a tumor suppressor (Jaulin-Bastard et al., 2001; Kolch, 2003; Dai et al., 2006). However, it is unknown how Erbin is ubiquitylated/degraded and by which E3 ubiquitin ligase, and more importantly, the biological significance of targeted Erbin degradation.

In this study, we report a serendipitous finding that skin-specific deletion of Sag E3 ubiquitin ligase significantly accelerates mutant KrasG12D-induced skin papillomagenesis as a result of the accumulation of Erbin and Nrf2, two novel substrates of Sag-βTrCP E3 ligase, that blocks reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation to promote proliferation. This result is completely opposite to our recent study in which Sag deletion significantly suppressed KrasG12D-triggered lung tumorigenesis (Li et al., 2014). Thus, Sag is an organ/tissue-specific, KrasG12D-cooperative or -antagonistic gene that is dependent on the tumor-suppressive or oncogenic nature of its substrates. Our study provides, to our best knowledge, the first in vivo demonstration that Sag functions as a suppressor of KrasG12D-induced skin tumorigenesis through degrading Erbin and Nrf2 to boost ROS generation, leading to induction of autophagy and senescence.

Results

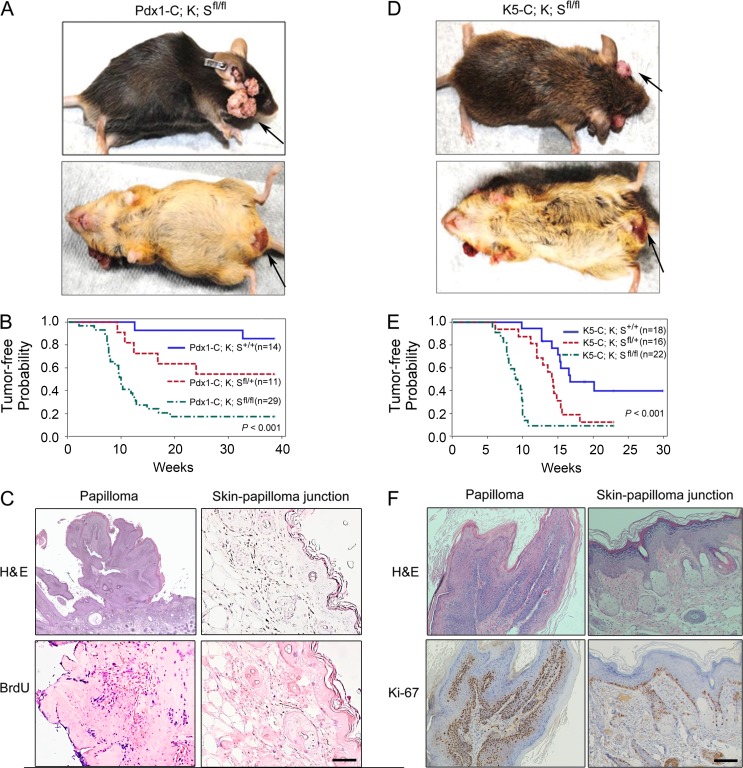

Sag deletion promotes KrasG12D-induced skin papilloma formation

We recently found that SAG is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer, which is associated with poor patient survival (unpublished data). We determined the role of Sag in pancreatic tumorigenesis by crossing conditional Sagfl/fl knockout (KO) mice (Li et al., 2014) with Pdx1-Cre;LSL-KrasG12D mice, a mouse pancreatic cancer model (Hingorani et al., 2003). Deletion, driven by Pdx1-Cre, of the STOP fragment (LSL, flox-STOP-flox) in the LSL-KrasG12D allele and floxed exon 1 of Sag (Li et al., 2014) simultaneously activated KrasG12D and inactivated Sag. Unexpectedly, Sag deletion accelerated KrasG12D-induced skin papillomagenesis long before the formation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Specifically, in Pdx1-Cre;KrasG12D;Sagfl/fl (designated as Pdx1-C;K;Sfl/fl) mice, skin tumors developed in facial and anus-surrounding tissues with an incidence of 82.8% and latent period of 10 wk, as compared with a 14.3% incidence and >38-wk latent period in control Pdx1-Cre;KrasG12D;Sag+/+ (Pdx1-C;K;S+/+) mice. The incidence (45.5%) fell in between in heterozygous Pdx1-C;K;Sfl/+ mice (Fig. 1 A and Fig. S1 A). These data were plotted with tumor-free probability versus time (weeks) and were found to be statistically significant among three Sag genotypes (Fig. 1 B). Histological examination confirmed that tumors are papilloma in nature and tumor tissues are highly proliferative as compared with adjacent skin tissues (Fig. 1 C). We also confirmed the KrasG12D activation and Sag deletion in three independent papilloma tissues derived from Pdx1-C;K;Sfl/fl mice with corresponding normal skin tissues as negative controls (Fig. S1 B). Thus, by shortening the latent period and increasing the incidence, Sag deletion significantly accelerated the formation of papillomas induced by KrasG12D. The lack of 100% penetration of tumor formation may be attributable to <100% efficiency of Pdx1-Cre–mediated removal of the STOP fragment that activates KrasG12D.

Figure 1.

Sag deletion accelerates the formation of KrasG12D-induced skin papillomas. (A) Appearance of skin tumors on face and anus of Pdx1-Cre;Kras;Sagfl/fl (Pdx1-C;K;Sfl/fl) mice. (B) Tumor-free probability versus time in mice with the indicated genotypes. (C) Representative images of papillomas and adjacent skin tissues in Pdx1-C;K;Sfl/fl mice. Tissue sections were processed for H&E and BrdU staining. (D) Appearance of skin tumors on face and anus of K5-Cre;Kras;Sagfl/fl (K5-C;K;Sfl/fl) mice. (E) Tumor-free probability versus time in mice with the indicated genotypes. (F) Representative images of papillomas and adjacent skin tissues in K5-C;K;Sfl/fl mice. Tissue sections were processed for H&E and Ki-67 staining. Bars, 100 µm.

Although a recent study clearly showed that Pdx1 is indeed expressed in the epidermis (Mazur et al., 2010), we went on to further confirm this observation by generating the same KrasG12D;Sagfl/fl mice, but with targeted deletion in the skin driven by well-characterized skin-specific K5-Cre (designated as K5-C;K;Sfl/fl or their wild-type control K5-C;K;S+/+ mice). Again, Sag deletion increased the probability of papilloma formation in the same facial and anus-surrounding areas with an incidence of 90.9% and latent period of 9.1 wk, as compared with a 55.6% incidence and 16.7 wk of latency period in wild-type control mice, and the differences are statistically different (Fig. 1, D and E; and Fig. S1 C). The shortened latent period seen in both K5-C;K;Sfl/fl and K5-C;K;S+/+ mice may be attributable to a higher level of Kras expression driven by stronger K5-Cre in the epidermis. Again, tumors were papilloma in nature with high rates of proliferation (Fig. 1 F), resulting from expected KrasG12D activation and Sag deletion (Fig. S1 D). Collectively, these data demonstrate that Sag deletion accelerates the formation of KrasG12D-induced skin papillomas with a much higher incidence and shorter latent period.

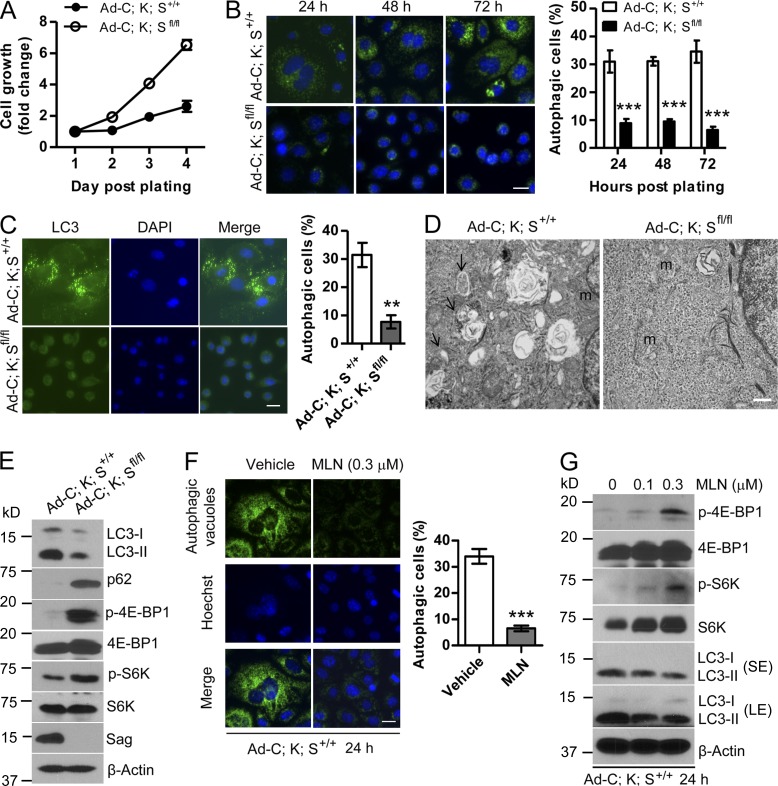

Sag deletion inhibits KrasG12D-induced autophagy in keratinocytes

To elucidate the mechanism by which Sag deletion accelerates papillomagenesis triggered by KrasG12D activation, we established primary keratinocytes from dorsal skin of neonatal K;S+/+ and K;Sfl/fl pups (p1–2). After Ad-Cre infection, KrasG12D was activated and Sag was deleted in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl keratinocytes (Fig. S2, A and B). Compared with Ad-C;K;S+/+ control, Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells grew much faster (Fig. 2 A). Morphologically, whereas Ad-C;K;S+/+ control cells had an enlarged and flattened appearance with numerous autophagic vacuoles in the cytoplasm, Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells were much smaller, with healthy roundness, and were free of autophagic vacuoles (Fig. S2 C, left panels). Immunostaining of the cells with a Cyto-ID autophagy detection kit and LC3 antibody confirmed that 30–35% of Ad-C;K;S+/+ control cells underwent autophagy, which was reduced to 10% upon Sag deletion (Fig. 2, B and C). Similar results were obtained in keratinocytes derived from pups with genotypes of K5-C;K;S+/+ versus K5-C;K;Sfl/fl (Fig. S2, C [right panels] and D [left panels]) as well as tumor cells derived from papilloma tissues developed in Pdx1-C;K;S+/+ versus Pdx1-C;K;Sfl/f mice (Fig. S2 D, right panels). The EM analysis further confirmed the presence of an increased number of autophagosomes in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells (Fig. 2 D). Finally, immunoblotting (IB) revealed in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells a reduced level of p62 and an increased conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II, two well-used autophagy biomarkers (Fig. 2 E). Thus, KrasG12D activation induces autophagy in keratinocytes, which is inhibited by Sag deletion.

Figure 2.

Sag deletion inhibits autophagy. (A) Keratinocytes with the indicated genotypes were measured after Ad-Cre administration for growth rate by ATPlite-based cell proliferation assay (n = 8). (B and C) Keratinocytes with the indicated genotypes were plated and stained at various time points with Cyto-ID autophagy detection kit (B) or with LC3 antibody (C). Cells containing >10 autophagic vacuoles (B) or five LC3 dots (C) were counted as autophagic cells. The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats. For the experiment shown, at least 200 cells were counted in each group. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D) Autophagic vacuoles (arrows) were detected by transmission EM. m, mitochondria. Bar, 500 nm. (E) Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to IB. (F) Ad-C;K;S+/+ keratinocytes were treated with MLN4924 (MLN) for 24 h and subjected to autophagy staining. Cells with >10 autophagic vacuoles were counted as autophagic cells. The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats. For the experiment shown, at least 300 cells were counted in each group. Hoechst, Hoechst 33342. ***, P < 0.001. (G) Ad-C;K;S+/+ keratinocytes were treated with MLN4924 for 24 h and subjected to IB. LE, long exposure; SE, short exposure. Error bars indicate the SEM. Bars (B, C, and F), 20 µm.

Given a predominant role played by mTORC1 in the blockage of autophagy, we compared mTORC1 activity in Ad-C;K;S+/+ versus Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells and found that Sag deletion activated mTORC1, as reflected by increased phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K (Fig. 2 E). Consistently, treatment of Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells with the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin significantly induced autophagy with a percentage of autophagic cells similar to that of Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells, thus rescuing the Sag deletion effect (Fig. S2 E). On the other hand, treatment of Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells with MLN4924, a small-molecule inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme, which, by blocking cullin neddylation, inhibited SAG-associated ligase activity (Soucy et al., 2009), mimicked Sag deletion by inhibiting autophagy to the level seen in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 2 F). Consistently, MLN4924 treatment of Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells caused a dose-dependent activation of mTORC1 activity along with a dose-dependent reduction of LC3-I to LC3-II conversion (Fig. 2 G). Thus, Sag inactivation by genetic or pharmacological approaches inhibits KrasG12D-induced autophagy in keratinocytes via mTORC1 activation.

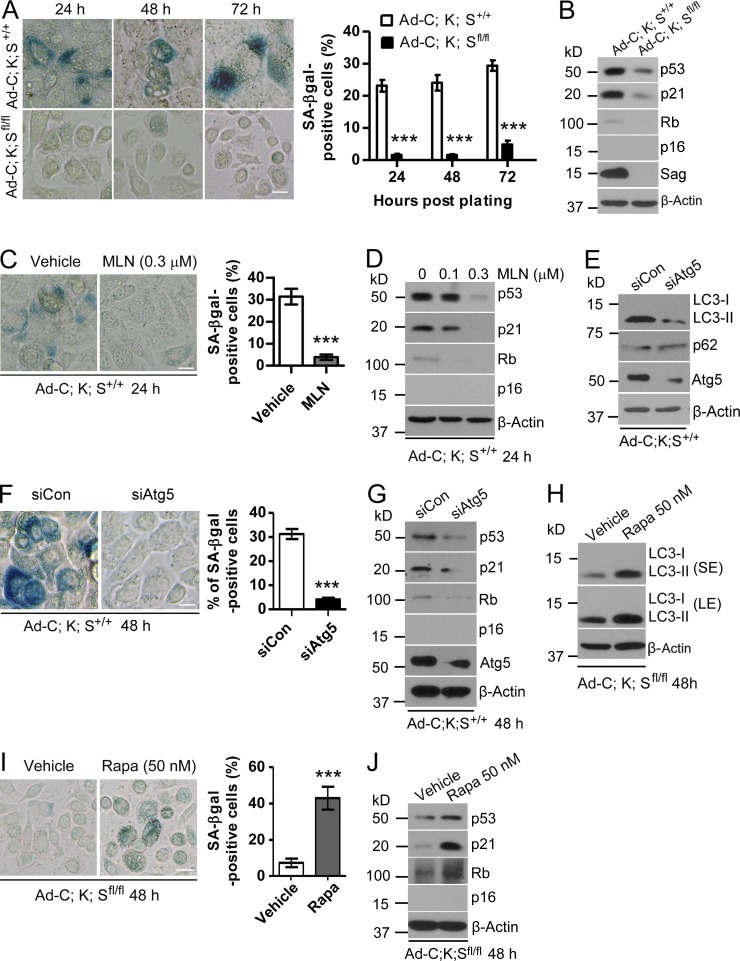

Sag deletion inhibits KrasG12D-induced senescence in keratinocytes

Cellular senescence is an important mechanism to limit cell proliferation (Rodier and Campisi, 2011), and Ras activation has previously been shown to induce senescence in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (Serrano et al., 1997). We therefore determined whether KrasG12D induces senescence in keratinocytes and whether Sag deletion blocks it as a mechanism of promoting proliferation. By using senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining, we found ∼20–30% of Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells underwent senescence in a time-dependent manner, whereas <5% of Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells were senescent (Fig. 3 A). A time-dependent induction of senescence was also observed in Pdx1-C;K;S+/+, but not in Pdx1-C;K;Sfl/fl, tumor cells (Fig. S3 A). Finally, a higher percentage of the senescent population was seen in K5-C;K;S+/+ than in K5-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. S3 B). Thus, Sag deletion blocked KrasG12D-induced senescence in keratinocytes. Mechanistically, KrasG12D-induced senescence appeared to be mediated by the p53/p21 axis, rather than the Rb/p16 axis, because the higher levels of p53/p21 were seen in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells, whereas the p16 level was undetectable in both lines (Fig. 3 B). Consistently, pharmacological inhibition of Sag E3 by MLN4924 blocked senescence in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells (Fig. 3 C) with a corresponding reduction of p53/p21 levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3 D). Thus, Sag is required for maximal induction of senescence by KrasG12D in mouse keratinocytes, and attenuation of senescence upon Sag deletion contributes to an increased proliferation.

Figure 3.

Sag deletion inhibits senescence. (A, C, F, and I) Keratinocytes with the indicated genotypes were plated and stained at various time points with X-gal (A), treated with the indicated drugs for various periods of time (C and I), or transfected with siAtg5 (F), followed by X-gal staining. The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats. For the experiment shown, the percentage of green positive cells out of a total of >300 cells counted is plotted. Error bars indicate the SEM. ***, P < 0.001. Bars, 20 µm. (B, D, E, G, H, and J) Cell lysates were prepared from cells either left untreated (B), transfected (E and G), or treated with the indicated drugs (D, H, and J) for IB. Rapa, rapamycin; LE, long exposure; SE, short exposure.

KrasG12D-induced autophagy and senescence is a sequential event

We next determined whether KrasG12D-induced autophagy and senescence occur sequentially. siRNA silencing of Atg5 in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells inhibited autophagy (Fig. 3 E) and significantly suppressed senescence (Fig. 3 F) with a corresponding reduction of p53 and p21 (Fig. 3 G). Similar results were observed when Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells were treated with chloroquine (CQ), a small-molecule inhibitor of autophagy (Fig. S3, C and D). Thus, blockage of autophagy using both genetic and pharmacological approaches suppressed senescence triggered by Kras activation. Reciprocally, induction of autophagy by rapamycin in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 3 H) significantly increased the senescence population (Fig. 3 I) with a corresponding increase in p53 and p21 levels (Fig. 3 J). Collectively, our results demonstrate that KrasG12D-induced autophagy and senescence are sequential events, with autophagy occurring first and being a prerequisite for senescence, and that the process requires Sag.

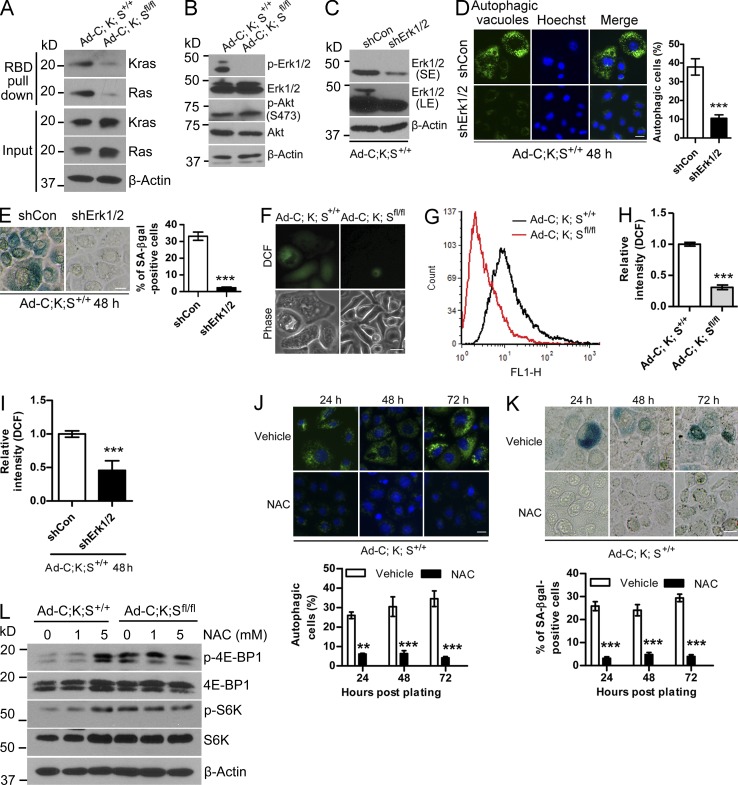

Erk activation and ROS accumulation are responsible for KrasG12D-induced autophagy and senescence

To elucidate the underlying mechanism(s) by which Sag deletion prevented KrasG12D-induced autophagy and senescence, we first determined the effect of Sag deletion on Kras activity by a Ras-binding domain (RBD) of Raf-1 pull-down assay and found that activities of Kras and its downstream effector Erk1/2 were significantly reduced in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells as compared with the control Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells (Fig. 4, A and B). On the other hand, Sag deletion had no effect on Akt activation (Fig. 4 B). We next silenced Erk1/2 in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells and observed a significant reduction of autophagy and senescence (Fig. 4, C–E). Similar results were seen when Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells were treated with the Mek-specific inhibitor PD98059 (Fig. S4, A and B). Thus, by inactivation of Kras activity and the subsequent Ras-Raf-Mek-Erk pathway, Sag deletion suppresses autophagy and senescence to promote proliferation.

Figure 4.

Ras–Raf–Erk signaling and ROS regulates autophagy and senescence in keratinocytes. (A) Cell lysates were prepared for Ras activity using the RBD of the Raf pull-down assay, followed by IB. (B) Cell lysates were prepared for IB. (C–E) Keratinocytes were transfected with shErk1/2, followed by IB (C), measurement of autophagy (D), and senescence (E). The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats. For the experiment shown, a total of 200 cells were counted in each group. (F–I) Cells with the indicated genotypes were left untreated (F–H) or were transfected with shErk1/2 (I), followed by staining with DCFHDA. The ROS levels were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (F) or flow cytometry (G–I). Results shown are representative of two independent experiments (F and G). (H) Quantification of the experiment described in G (n = 2). (I) Quantification of ROS levels (n = 2). (J and K) Ad-C;K;S+/+ keratinocytes were left untreated or were treated with 5 mM NAC for various periods of time, followed by staining to detect autophagy (J) or senescence (K). The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats. For the experiment shown, a total of 350 cells were counted in each group. (L) Cell lysates were prepared after NAC treatment for 48 h, followed by IB. Error bars indicate the SEM. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bars, 20 µm.

Previous studies have shown that Ras-Erk activation caused ROS accumulation, which could prevent cell proliferation by induction of autophagy and senescence (Moon et al., 2010; Qi et al., 2013; Zamkova et al., 2013). We therefore used 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFHDA) staining and then analyzed ROS by both microscopy and flow cytometry and found that the ROS levels were significantly higher in Ad-C;K;S+/+ than in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 4, F–H). More importantly, Erk activation, ROS production, and autophagy/senescence induction were causally related because Erk1/2 silencing or PD98059 treatment of Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells reduced the ROS levels (Fig. 4 I and Fig. S4 C) and significantly blocked autophagy and senescence (Fig. 4, D and E; and Fig. S4, A and B). Reciprocally, H2O2 treatment of Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells induced autophagy and senescence (Fig. S4, D and E), indicating that ROS played a causal role. Furthermore, treatment of Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells with ROS scavenger N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) remarkably blocked autophagy and senescence (Fig. 4, J and K). Finally, we determined whether ROS is responsible for the mTORC1 inactivation seen in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells, a phenomenon reported in a few other cellular systems (Alexander et al., 2010; Qi et al., 2013). Indeed, NAC treatment of Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells activated mTORC1 activity to the levels similar to that of Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 4 L). Thus, ROS, accumulated as a result of Kras-Erk activation, is responsible for mTORC1 inactivation and subsequent induction of autophagy and senescence, which is blocked by Sag deletion.

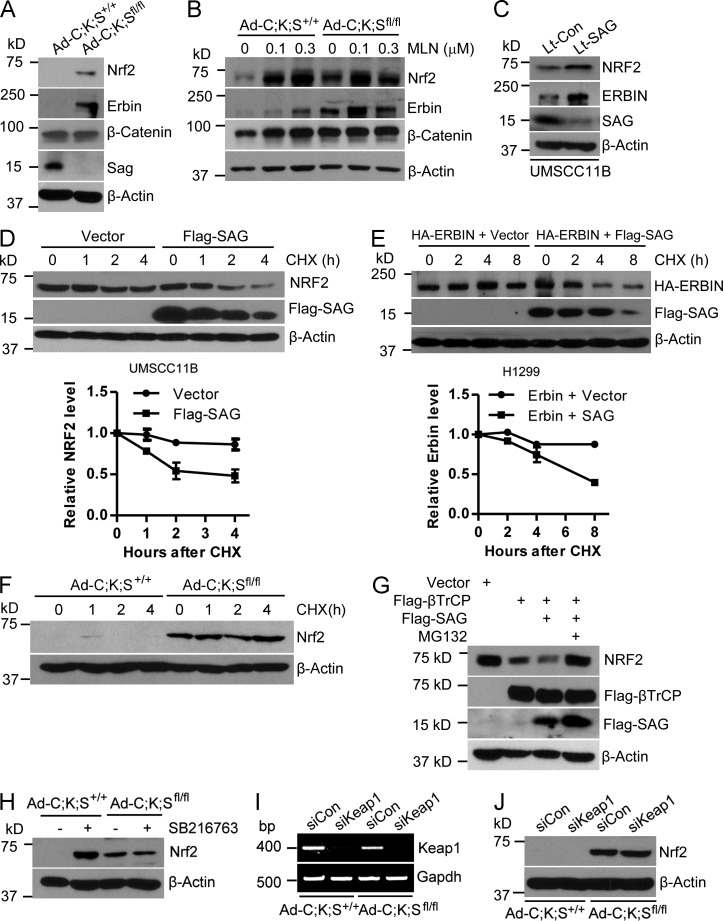

Sag deletion causes accumulation of Nrf2 and Erbin

To determine how Sag deletion blocked ROS generation in KrasG12D-activated keratinocytes, we first focused on Nrf2, a known antioxidant transcription factor (DeNicola et al., 2011) and known substrate of SCFβTrCP E3 ligase (Rada et al., 2011), whose activity requires Sag or its family member Rbx1 (Wei and Sun, 2010). Significantly, although it was undetectable in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells, Nrf2 was remarkably accumulated in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 5 A). Because Kras activity was substantially reduced in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells, we also measured the protein levels of Erbin, which is known to suppress Raf activation by disrupting the Shoc2–Ras–Raf complex, thus negatively regulating the activity of the Ras–Raf–Mek–Erk pathway (Huang et al., 2003). Remarkably, although it was undetectable in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells, Erbin was significantly accumulated upon Sag deletion (Fig. 5 A), consistent with the inactivation of Erk activity (Fig. 4 B). No difference was seen between Ad-C;K;S+/+ and Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells in the levels of β-catenin (Fig. 5 A), another known substrate of SCFβTrCP E3 ligase (Hart et al., 1999; Kitagawa et al., 1999), showing the selectivity of Sag’s effect. Furthermore, treatment with MLN4924 caused a dose-dependent accumulation of Nrf2 and Erbin in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells but had no effect on Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 5 B). Consistently, lentivirus-based SAG silencing in human head and neck squamous carcinoma UMSCC11B cells (Yang et al., 2011) caused the accumulation of both Nrf2 and Erbin (Fig. 5 C), whereas SAG overexpression shortened the protein half-life of both NRF2 (Fig. 5 D) and Erbin (Fig. 5 E). Moreover, NRF2 protein was hardly degraded for up to 4 h in the absence of Sag (Fig. 5 F), whereas the SAG-βTrCP combination further reduced NRF2 levels, a process completely rescued by MG132 (Fig. 5 G).

Figure 5.

Sag regulates the levels of Nrf2 and Erbin. (A and B) Cell lysates were prepared for IB (A), or cells were treated with various concentrations of MLN4924 (MLN), followed by IB (B). (C) Human head and neck carcinoma UMSCC11B cells were either infected with Sag silencing lentivirus or scrambled control, followed by IB. (D) UMSCC11B cells were transiently transfected with Flag-tagged SAG plasmid or the vector control, followed by cycloheximide (CHX) treatment for various time points and were harvested for IB. (E) Human lung H1299 cells were transiently cotransfected with Erbin plus vector control or Erbin plus Flag-tagged SAG, followed by CHX treatment for various time points and harvested for IB. (D and E, top) The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of two repeats. (D and E, bottom) Relative NRF2 and Erbin levels were quantified (n = 2). (F) Cells were treated with CHX for different time periods and subjected to IB. (G) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 48 h. Cells were treated with or without MG132 for 3 h, followed by IB. (H) Cells were left untreated or were treated with 10 µM SB216763 for 24 h, followed by IB. (I and J) Cells were transfected with siKeap1 or control siRNA, followed by RT-PCR (I) or IB (J). Error bars indicate the SEM.

Because previous studies have shown that βTrCP-mediated Nrf2 degradation requires GSK-3β–mediated phosphorylation of Nrf2 at the Asp-Ser-Gly-Ile-Ser motif and the GSK-3–specific inhibitor SB216763 increased Nrf2 levels (Rada et al., 2012; Chowdhry et al., 2013), we determined the effect of GSK-3β by treating the paired keratinocytes with the GSK-3–specific inhibitor SB216763 and found that the inhibitor significantly induced Nrf2 levels in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells but had no effect on Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 5 H). Finally, although Keap1/Cul3 E3 ligase was reported to promote NRF2 degradation (Furukawa and Xiong, 2005), we found that Keap1 silencing had no effect on Nrf2 levels in either of the paired keratinocytes (Fig. 5, I and J). Collectively, our results demonstrate that, in keratinocytes, Sag is an essential component and is required for targeted degradation of Nrf2 by βTrCP E3 and in a manner independent of Keap1/Cul3 E3.

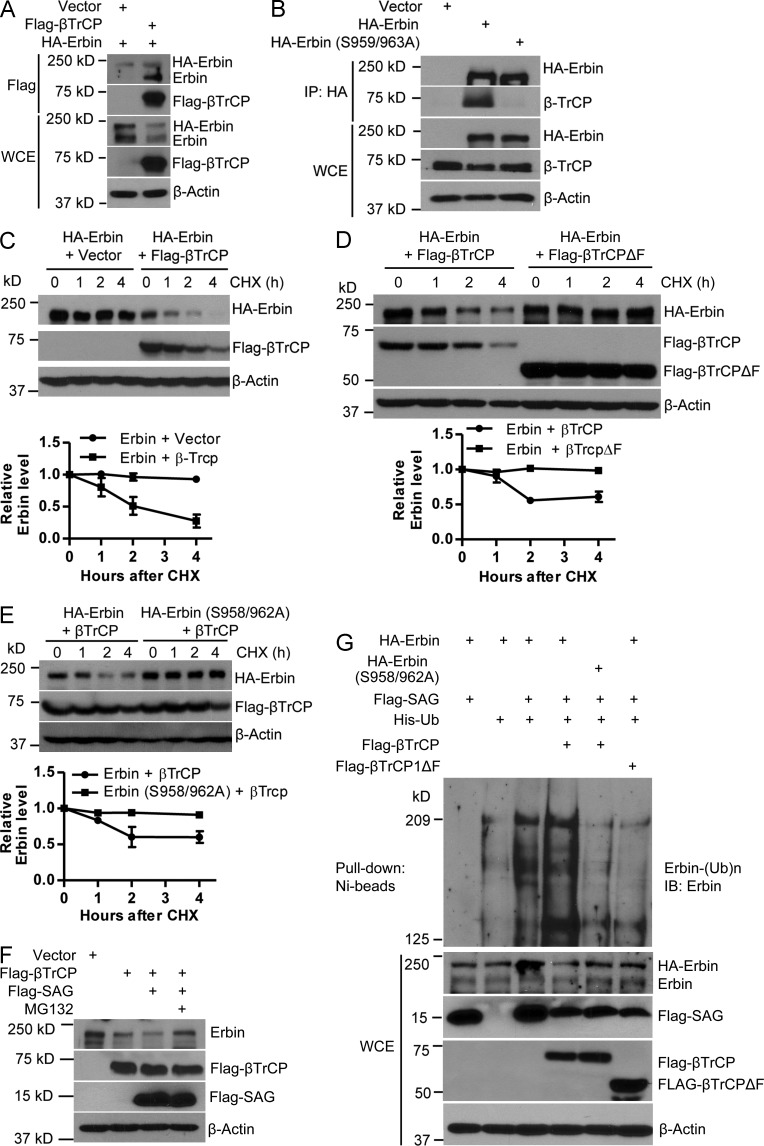

SAG-βTrCP promotes Erbin ubiquitylation and degradation

Although Erbin has been extensively studied for its biological functions (Kolch, 2003; Dan et al., 2010), it is totally unknown how it is degraded. Having established that SAG promotes Erbin degradation, we went on to identify the F-box protein that directly recognizes Erbin. Examination of the Erbin protein sequence revealed an evolutionarily conserved consensus binding motif (DSGXXS) for βTrCP at codons 958–963 (TSGPQS) with one T to D mismatch (Fig. S5 A). In a cotransfection experiment, we found that both endogenous and exogenous Erbin were readily detected in βTrCP immunoprecipitates (Fig. 6 A). Reciprocally, wild-type Erbin, but not its S959/963A mutant, pulled down endogenous βTrCP1 (Fig. 6 B). Significantly, wild-type βTrCP1, but not its F-box domain–deleted mutant (βTrCP1ΔF), shortened the Erbin protein half-life (Fig. 6, C and D) but failed to shorten the protein half-life of this Erbin mutant (Fig. 6 E). Furthermore, a βTrCP1-mediated decrease in both endogenous and exogenous Erbin was enhanced by SAG cotransfection, which is largely blocked by MG132, whereas the βTrCP-SAG combination had no effect on the protein half-life of the Erbin mutant (Fig. 6 F and Fig. S5 B). Finally, SAG promoted Erbin polyubiquitylation, which was further enhanced by βTrCP1, but not by βTrCP1ΔF, whereas the SAG-βTrCP1 combination failed to promote polyubiquitylation of the Erbin mutant (Fig. 6 G). Thus, Erbin is a novel substrate of SAG-βTrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase for targeted ubiquitylation and degradation.

Figure 6.

SAG-βTrCP promotes Erbin ubiquitylation and degradation. (A and B) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 48 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag (A) or anti-HA (B) antibody and IB. (C–E) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 48 h. Cells were treated with CHX for different time periods and harvested for IB. The band density was quantified by AlphaEaseFC software. (top) The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of two repeats. (bottom) Relative Erbin level was quantified (n = 2). (F) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. 48 h later, cells were treated with or without MG132 for 3 h, followed by IB. (G) H1299 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, lysed with 6 M guanidine solution, pulled down with Ni-bead, and followed by IB for Erbin, or cell lysates were subjected to direct IB. WCE, whole cell extract. Error bars indicate the SEM.

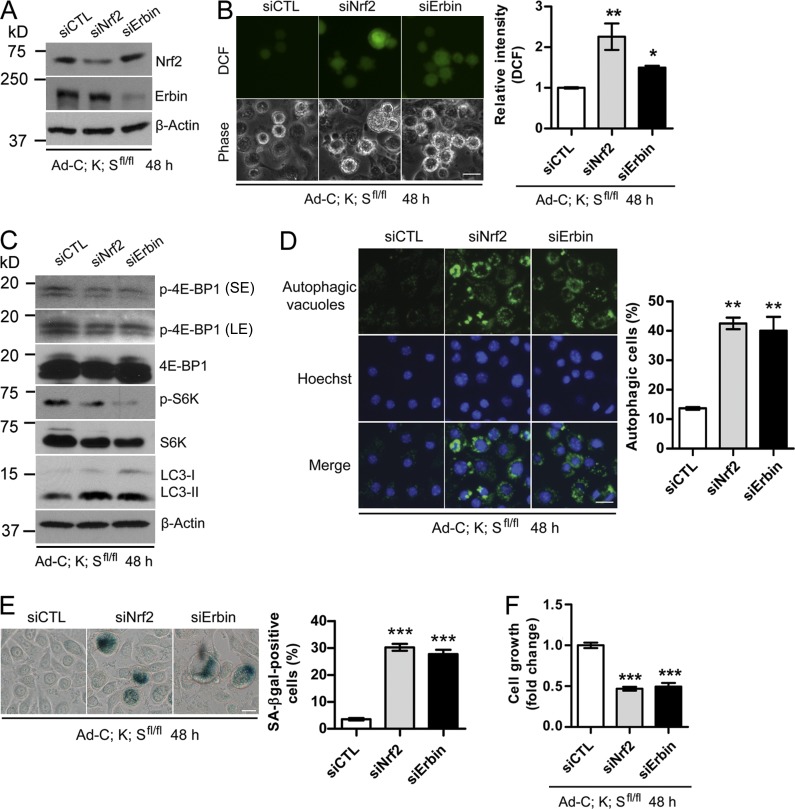

Targeted siRNA knockdown of Nrf2 or Erbin rescues the phenotypes induced by Sag deletion

Given that both Nrf2 and Erbin are substrates of Sag-βTrCP E3 ligase, we next determined the functional significance of their accumulation in mediating the phenotypic changes induced by Sag deletion. siRNA-based knockdown of Nrf2 or Erbin in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells (Fig. 7 A) caused significant ROS accumulation (Fig. 7 B) and mTORC1 inactivation (Fig. 7 C), with induction of autophagy (Fig. 7 D) and senescence (Fig. 7 E) leading to growth suppression (Fig. 7 F). Similar results were seen when an independent Erbin-targeting shRNA was used (Fig. S5, C–G).

Figure 7.

Silencing of Nrf2 or Erbin rescues the phenotypes induced by Sag deletion. (A–C) Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl keratinocytes were infected with siRNA targeting either Nrf2 or Erbin, followed by IB (A and C), or ROS measurement by DCFHDA staining and photographed with a fluorescence microscope (B, left) and quantified with a flow cytometer (B, right; n = 2). (D–F) Autophagy was detected using the Cyto-ID autophagy detection kit (D), senescence using X-gal staining (E), and cell proliferation by ATPlite assay kit (F; n = 5). The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats. For the experiment shown, a total of 300 cells were counted in each group (D and E). Error bars indicate the SEM. LE, long exposure; SE, short exposure. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bars, 20 µm.

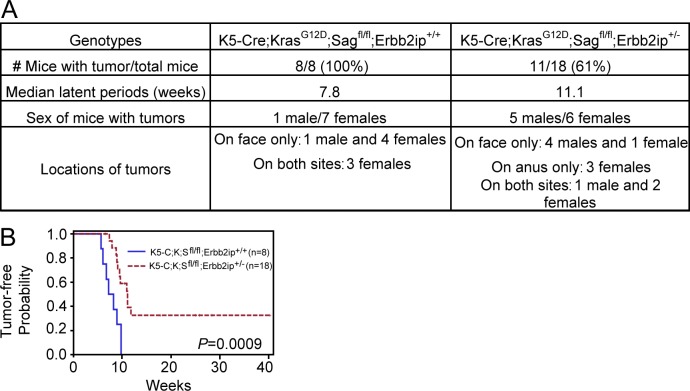

Genetic deletion of Erbb2ip delays papillomagenesis

More significantly, we performed an in vivo rescue by a genetic KO approach because total KO of Erbb2ip, a gene encoding Erbin, has no phenotype (Tao et al., 2009). We crossed Erbb2ip−/− mice with K5-C;K;Sfl/fl mice in an attempt to obtain Erbb2ip and Sag double KO mice with activated KrasG12D in the skin (K5-C;K;Sfl/fl;Erbb2ip−/−). After multiple rounds of crossing, we were able to generate only one such mouse, which died for an unknown reason at age 15 wk without any sign of skin papillomas. On the other hand, simultaneous deletion of Erbb2ip with even one allele (n = 18) delayed the latent period for papilloma formation with reduced incidence (Fig. 8 A), although to a lesser extent as compared with K5-C;K;S+/+ wild-type mice (Fig. 1). The difference is statistically significant (Fig. 8 B), demonstrating a partial rescue. Collectively, both cell culture and KO experiments showed that accumulated Nrf2 and Erbin, resulting from Sag deletion, play the causal role in preventing Kras-induced ROS production, thus maintaining mTORC1 in an active status to block autophagy and senescence, leading to increased proliferation and accelerated papillomagenesis.

Figure 8.

Genetic deletion of Erbb2ip delays papillomagenesis. (A) Summary of tumor incidence, median latent time period for tumor formation, and tumor location in mice with the indicated genotypes. (B) Tumor-free probability versus time in mice with the indicated genotypes. The median for the latent period is 55 d for K5-C;K;Sfl/fl;Erbb2ip+/+ versus 78 d for K5-C;K;Sfl/fl;Erbb2ip+/−.

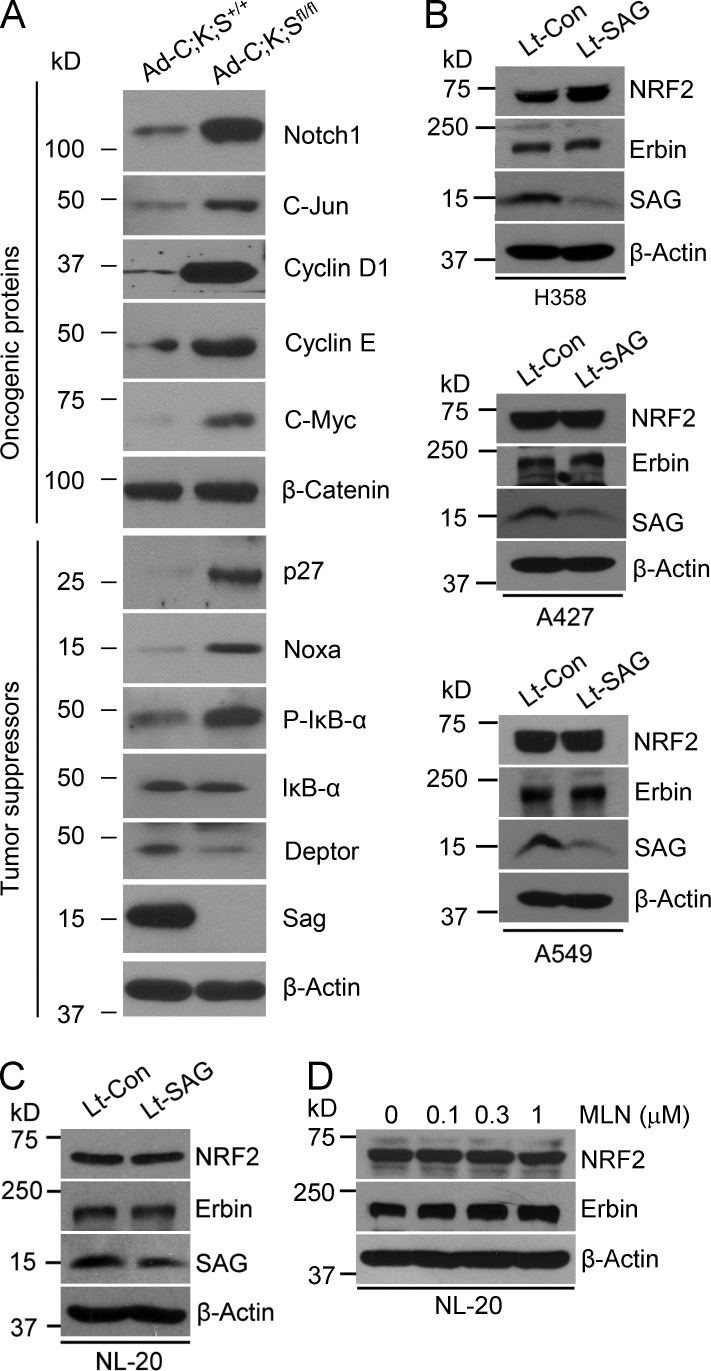

Nrf2 and Erbin were not accumulated in lung cancer cells or bronchial epithelial cells upon Sag silencing or inactivation

Finally, we comparatively assessed the different roles of Sag in the lung versus the skin under Kras-activated conditions by measuring the levels of oncogenic and tumor-suppressive substrates of SAG E3 after Sag depletion. In KrasG12D-immortalized primary keratinocytes, Sag deletion caused the accumulation of, in addition to Nrf2 and Erbin, both oncogenic (Notch, c-Myc, c-Jun, and cyclin D and E) and tumor-suppressive (e.g., pIκBα, p27, and Noxa) substrates (Fig. 9 A). A decrease was seen in DEPTOR (Fig. 9 A), a naturally occurring inhibitor of mTORC (Peterson et al., 2009), which may explain mechanistically why mTORC1 is activated in these cells. Nevertheless, this result was in contrast to what was observed in three lung cancer cell lines, all harboring Kras mutation at codon 12, in which only tumor-suppressive substrates (e.g., p21/p27, NOXA, pIκBα, and DEPTOR) were accumulated upon Sag silencing (Li et al., 2014). Furthermore, in all three lung cancer cell lines, SAG silencing caused the accumulation of neither NRF2 nor Erbin (Fig. 9 B). Finally, we determined the effect of SAG inactivation on the levels of NRF2 and Erbin using NL-20 normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Lentivirus-based SAG silencing does not change the protein levels of NRF2 and Erbin (Fig. 9 C), which is consistent with the effect of SAG silencing on human lung cancer cells (Fig. 9 B). In addition, we treated cells with various concentrations of MLN4924, an indirect inhibitor of Sag E3 ligase, via cullin deneddylation and found that MLN4924 did not change the levels of either Erbin or NRF2 (Fig. 9 D). In contrast, MLN4924 treatment significantly increased the levels of both Erbin and NRF2 in Sag wild-type (Ad-C;K;S+/+) keratinocytes (Fig. 5 B), suggesting the effect of Sag is cell type dependent. Thus, it appears that in keratinocytes, the effect of these oncogenic and tumor-suppressive substrates may cancel each other, with the effect of Nrf2/Erbin being critical, whereas in lung cell types, particularly lung cancer cells, accumulated tumor-suppressive substrates act together to block KrasG12D-induced tumorigenesis (Li et al., 2014). Collectively, our study suggests that Sag is a tissue-specific, KrasG12D-cooperative oncogenic or anti-KrasG12D tumor-suppressive protein, with its ultimate function dependent on tissue-specific expression of its key substrates.

Figure 9.

Differential accumulation of SAG substrates in keratinocytes versus lung cells. (A–D) IB for keratinocytes with the indicated genotypes (A); three lines of lung cancer cells after infection with lentivirus-based SAG silencing (Lt-SAG) and scramble siRNA control (Lt-Con; B); NL-20 bronchial epithelial cells after SAG silencing for 48 h (C); and MLN4924 treatment for 24 h (D).

Discussion

Sag deletion accelerates skin papillomagenesis induced by KrasG12D activation

Mutations in Ras oncogenes are found in 10–30% of human skin squamous cell carcinoma (Spencer et al., 1995). Although the H-ras mutation is responsible for initiation of skin tumors in the DMBA-TPA chemical carcinogenesis model (Balmain and Pragnell, 1983), mutant Kras has a similar initiating activity as indicated by skin carcinogenesis in N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine–treated mice (Rehman et al., 2000). In this study, we used LSL-KrasG12D knock-in and Sag conditional KO mouse models with skin-targeted activation of Kras alone or in combination with inactivation of Sag, driven by Pdx1-Cre or K5-Cre. We made the following interesting observations. (a) Although it has a long latent period, KrasG12D is sufficient to cause papilloma formation without an additional promoting agent, which is consistent with a few previous publications (Caulin et al., 2004; Vitale-Cross et al., 2004). (b) Skin tumors were only found on the face near the eyes and in the anus-surrounding areas. A majority of male mice developed facial papillomas only, whereas female mice developed the tumors in both locations. (c) KrasG12D-induced papilloma formation can be significantly accelerated by Sag deletion, as demonstrated by an increased incidence and shortened latent period. This accelerating effect can even be seen with one allele deletion of Sag. These data, in combination with our previous study showing that SAG transgenic skin expression extended the latent period during DMBA-TPA–induced skin papillomagenesis (Gu et al., 2007a), suggest that Sag has Ras antagonistic activity in the skin.

Sag deletion blocks autophagy and senescence induced by KrasG12D activation

Autophagy and senescence are two types of cell death that are interconnected in response to various stimuli (Young et al., 2009; Young and Narita, 2010). We showed here that KrasG12D activation induces both autophagy and senescence in mouse keratinocytes, with autophagy preceding senescence, because blockage of autophagy inhibits senescence. Importantly, Sag deletion, via preventing mTORC1 inactivation, remarkably inhibits autophagy and subsequent senescence and promotes the growth of keratinocytes. Likewise, pharmacological inactivation of Sag-associated E3 ligase by MLN4924 substantially inhibits autophagy and subsequent senescence in Ad-C;K;S+/+ keratinocytes, whereas mTORC1 inactivation by rapamycin remarkably induces autophagy and senescence in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl keratinocytes. We also found that induction of senescence is associated with the p53/p21 axis, but not the Rb/p16 axis. Manipulation of senescence by Sag deletion or treatment of small-molecule inhibitors (MLN4924 or rapamycin) causes corresponding changes in the levels of p21 and p53. Finally, it’s worth noting that we showed previously that MLN4924 is an effective inducer of autophagy and senescence in several human tumor cell lines (Jia et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2012). Here, we showed that MLN4924 can block these processes in KrasG12D-immortalized primary mouse keratinocytes. The complete opposite biological consequence of MLN4924 treatment suggests the importance of cellular context in determining the ultimate drug effects.

Sag deletion blocks the Ras–Erk signaling pathway and ROS generation via Nrf2 and Erbin

We next addressed two mechanistic questions as to how KrasG12D activation inactivates mTORC1 to induce autophagy/senescence and how Sag deletion rescues this effect. We focused on Ras activity and ROS levels because the entire signaling pathway is initiated by Kras activation, whereas Ras has previously been shown to induce ROS (Lee et al., 1999; Zamkova et al., 2013), which could induce autophagy (Azad et al., 2009) as well as block mTORC1 activity (Alexander et al., 2010). We found that Ras and Erk activities and ROS levels are substantially reduced upon Sag deletion. Blockage of Erk activity by siRNA silencing or treatment with a Mek inhibitor in Ad-C;K;S+/+ cells significantly reduces ROS levels and inhibits autophagy and senescence. A similar rescuing effect was seen with treatment of the antioxidant NAC, which scavenges ROS and reactivates mTORC1. It appears paradoxical that deletion of Sag, which encodes an antioxidant protein (Duan et al., 1999), would cause the reduction of ROS levels. Interestingly, we found that Sag deletion caused accumulation of (a) Nrf2, an antioxidant transcription factor (DeNicola et al., 2011) and known substrate of SCFβTrCP E3 ligase (Rada et al., 2011), and (b) Erbin, a naturally occurring inhibitor of Ras–Raf activation (Dai et al., 2006), previously not known to be degraded by Sag E3 ligase. Indeed, Sag deletion as well as MLN4924 treatment caused substantial accumulation of Nrf2 and Erbin to reduce ROS levels via scavenging (by Nrf2) or blocking production (by Erbin). Consistently, siRNA silencing of Nrf2 and Erbin in Ad-C;K;Sfl/fl cells causes ROS accumulation to suppress cell growth via inducing autophagy and senescence, whereas simultaneous deletion of one allele of an Erbin-encoding gene, Erbb2ip, in K5-C;K;Sfl/fl mice partially rescues the phenotype of accelerated skin tumor formation. Collectively, it appears that the combined effect of Nrf2/Erbin accumulation as a result of Sag deletion outcompetes the loss of the sulfhydryl-mediated antioxidant capacity of Sag (Duan et al., 1999), leading to ROS reduction.

Erbin is a novel substrate of Sag-βTrCP E3 ligase

For the first time, we fully characterized Erbin as a novel substrate of Sag-βTrCP E3 ligase by demonstrating that (a) Erbin binds to βTrCP in a βTrCP binding motif–dependent manner; (b) βTrCP shortens Erbin protein half-life in a binding site and ligase activity–dependent manner; (c) Sag and βTrCP promote Erbin polyubiquitylation in a binding site– and ligase activity–dependent manner; and (d) Sag-βTrCP–mediated Erbin degradation can be rescued by a proteasome inhibitor, MG132. Thus, Erbin joins a growing list of Sag substrates (Sun and Li, 2013), including NF1 (Tan et al., 2011b), a naturally occurring inhibitor of wild-type Ras.

Sag is a cell context–dependent oncogenic or tumor-suppressive cooperating gene

Our previous studies showed that Sag is a dual functional anti-apoptotic protein, acting alone as an antioxidant or as an E3 ligase when it forms a complex with other components of Cullin-RING ligases, and that Sag regulates epidermal transformation and skin tumorigenesis in a substrate-dependent manner (Sun and Li, 2013). Our most recent study using a Sag conditional KO mouse model with targeted Sag deletion in the lung showed that Sag is an oncogene-cooperating gene required for KrasG12D-induced lung tumorigenesis (Li et al., 2014) via a mechanism involving activation of NF-κB and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. Thus, in general, Sag appears to be a cellular survival oncogenic protein. Contrary to this finding, here we made an unexpected finding that Sag has a tumor-suppressive function during KrasG12D-induced skin papillomagenesis. Targeted Sag deletion in the skin driven by either Pdx1-Cre or K5-Cre significantly accelerated the formation of KrasG12D-induced skin papillomas with a much higher incidence and much shorter latent period. The mechanism involves accumulation of the Ras–Raf inhibitor Erbin and the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2, two substrates of Sag E3 ligase, to block ROS-induced, mTORC1 inactivation–mediated autophagy and senescence. In contrast, Erbin and Nrf2 are not involved in lung tumorigenesis triggered by Kras activation and Sag inactivation. The role of Sag in tumorigenesis may, therefore, be dependent on tissue-specific expression of its key substrates.

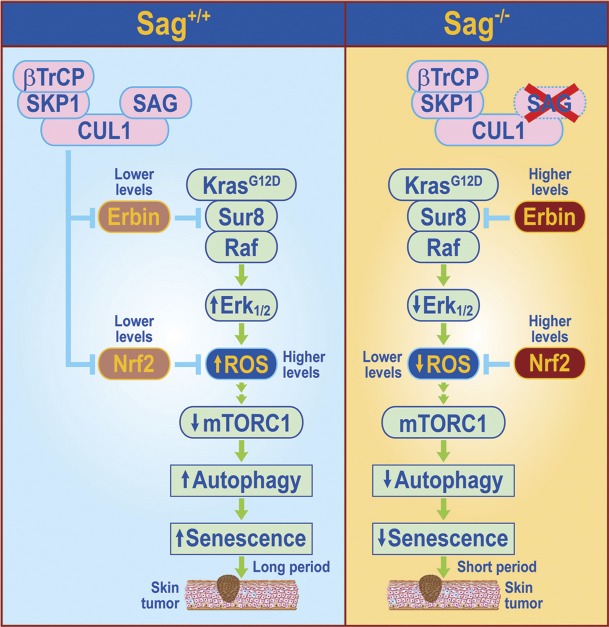

In summary, consistent with previous studies showing that ROS at high levels inhibits cancer cell growth, but at low levels promotes cell survival and tumorigenesis (Lluis et al., 2007; DeNicola et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2013; Satoh et al., 2013), we show here that the levels of ROS produced by KrasG12D activation of the MAPK signaling pathway play a major role in determining the latent period for skin tumor formation. Under Sag wild-type conditions, the levels of ROS generated by Kras activation are higher, which inhibit mTORC1 activity, leading to induction of autophagy and senescence in a subset of keratinocytes. Skin papillomas eventually developed, but with a much longer latent period and lower incidence. Under Sag-deleted conditions, two Sag substrates, Erbin and Nrf2, are accumulated to block Kras activation of Raf or to trans-activate antioxidant genes to scavenge ROS, respectively. Reduced levels of ROS relieve mTORC1 inactivation (Alexander et al., 2010; Qi et al., 2013), followed by inhibition of autophagy and senescence, leading to an accelerated rate for papilloma formation (Fig. 10). Our loss-of-function experiments, conducted in both in vitro cell culture and in vivo KO settings, suggest the causal role of Erbin and Nrf2 in accelerating skin tumorigenesis triggered by KrasG12D. Thus, Erbin acts as an oncogene in this setting to promote KrasG12D-induced skin papillomagenesis, which is consistent with our recent finding that Erbin promotes Neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis (Tao et al., 2014). The future study is directed to determining whether the Kras-Sag-Erbin/Nrf2 axis could also play a role in human skin tumorigenesis and whether the knowledge gained here can be used for early diagnosis, prognosis, and even treatment of skin cancer down the road.

Figure 10.

Model of the role of Sag in regulation of KrasG12D-induced papillomagenesis. Under Sag+/+ conditions, Kras activation initiates the MAPK signaling pathway to generate high levels of ROS, which block mTORC1 activity to induce autophagy and senescence in a subset of keratinocytes, delaying the process of skin papilloma formation. Upon Sag deletion, Sag substrates, Erbin, and Nrf2 accumulate. Increased Erbin binds to Sur8 to block Kras–Raf signaling, leading to reduced ROS production, whereas increased Nrf2 causes transcriptional activation of several antioxidant proteins (Kensler et al., 2007) to scavenge ROS. Reduced ROS relieves mTORC inactivation to block autophagy and senescence, leading to an accelerated papillomagenesis with a much shortened latent period and increased incidence.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

The overexpression experiments were performed using the following plasmids: pcDNA3-Flag-SAG, pcDNA3-His-ubiqutin, pKH3-HA-Erbin, pKH3-HA-Erbin (S958/962A), pIRES2-Flag-βTrCP1, and pIRES2-Flag-βTrCP1ΔF. These plasmids are all driven under the cytomegalovirus promoter.

Cell culture

Primary keratinocytes were isolated from dorsal skin of pups at p1–2 as described previously (Gu et al., 2007a; Lichti et al., 2008). In brief, newborn mice (1–2 d old) were sacrificed by CO2 and washed with 70% ethanol. Limbs and tails were amputated using scissors. Skin was cut on the dorsal side along the length of the body. The isolated skin was stretched, with dermal side down, on a 0.25% trypsin surface in a culture dish and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, the dermis was separated from the epidermis and suspended in high calcium minimum essential medium Eagle (EMEM; supplemented with 8% FBS, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 1 ng/ml keratinocyte growth factor, 1,000 U/ml penicillin, and 1,000 µg/ml streptomycin). The cell suspension was centrifuged at 150 g for 5 min at 4°C, resuspended in high calcium EMEM, and filtered through a 70-µm cell strainer (BD) into a new 50-ml conical tube. Cells were centrifuged at 150 g for 5 min at 4°C and resuspended in low calcium EMEM (supplemented with 8% FBS, 0.05 mM CaCl2, 1 ng/ml keratinocyte growth factor, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) for cell culture. For Cre recombinase-mediated gene deletion, keratinocytes were infected with Ad-Cre, along with control Ad-GPF virus, and harvested for PCR-based verification of Kras activation and Sag deletion. Keratinocytes were routinely cultured in complete EMEM (supplemented with 8% Ca2+-free FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin). All experiments were performed when cells were at passages between 3 and 9.

PCR-based genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from mouse tail tips and genotyped using the primers as follows. The primer set for the Sag floxed allele was PSAG-KO-F (5′-TTCTGGCCAGGTGTGGTGATATC-3′) and PSAG-KO-G (5′-CTTAGCCTTGGTTGTGTAGAC-3′) to detect the floxed allele (140 bp) and wild-type allele (105 bp). The primer set for detecting the removal of the Sag-targeting fragment (Fig. S2) was PSAGKO-Seq-B (5′-GTAACTCCAGACAATGCTCGCT-3′) and PSAG-KO-Seq-R (5′-TGAGTTCCAGGACAGCCAGGG-3′) with Sag deletion (275 bp) or without Sag deletion (1.6 kb). The primer set for KrasG12D activation was Kras-Cre F (5′-TCCGAATTCAGTGACTACAGA-3′) and Kras-Cre R (5′-CTAGCCACCATGGTCTGAGT-3′). The unrecombined 2 loxP band was ∼500 bp, whereas wild type was 620 bp. Upon recombination, the 500 bp was lost and a 650-bp 1 loxP band was present, which represents the recombined Kras mutant allele.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated by TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). RT-PCR was performed with the SuperScript III First-Strand synthesis system for RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To detect the mRNA levels of Keap1, we used the following primers: Keap1 forward (5′-GGTGTCCATCGAAGGCATCCA-3′) and reverse (5′-AGTCGATGCACGCGTGGAACA-3′) and GAPDH forward (5′-GTTGCCATCAATGACCCCTTC-3′) and reverse (5′-GCAGGGATGATGTTCTGG-3′). GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Immunohistochemical staining

Mouse skin tumors were isolated, fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut in 5-µm-thick sections for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Ki-67 staining. For BrdU staining, mice were injected with BrdU 2 h before euthanasia. Tumor tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and sectioned. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the ABC Vectastain kit (Vector Laboratories) with mouse anti-BrdU (1:1,000; 11299964001; Roche) and rabbit anti–Ki-67 (1:2,000; AB9260; EMD Millipore). Sections were developed with DAB and counterstained with eosin for BrdU and hematoxylin for Ki-67 staining. The expression of SA-β-gal was determined by SA-β-gal staining (Jia et al., 2011). In brief, cells were washed with PBS three times, fixed with 10% formalin for 10 min, washed with pH 6.0 PBS two times, and stained with SA-β-gal for 3 h at 37°C in the dark. Slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories), and images were taken with a 1 × 71 microscope (Olympus) using a 20 × 0.40 NA objective camera (DS-Fi1; Nikon) and acquisition software NIS-Elements BR 4.00.03 (Nikon). The experiments were performed at an RT of 25°C. All images were prepared with Photoshop CS2 (Adobe).

Lentivirus or siRNA transfection

Nrf2 siRNA (sc-37049), a pool of siRNAs, was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Other siRNAs were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific targeting the following sequences: lentivirus-based siRNA against SAG (Lt-SAG; 5′-GAGGACUGUGUUGUGGUCU-3′), siATG5 (5′-GGATGAGATAACTGAAAGdTdT-3′), siKeap1 (5′-ATATCTACATGCACTTCGGGG-3′), and siErbin (5′-UAGACUGACCCAGCUGGAAdTdT-3′); H1 promoter-driven shRNA against Erk1 (5′-CATGAAGGCCCGAAACTAC-3′); H1 promoter-driven shRNA against Erk2 (5′-GCGCTTCAGACATGAGAAC-3′); and PLL3.7 vector bone and driven under mouse U6 promoter shRNA targeting Erbin (5′-GCATCCCTCTAGAGAACAACT-3′). Scrambled siRNA (siCTL) was used as a control (5′-AUUGUAUGCGAUCGCAGAC-3′). In brief, cells were transfected with lentivirus control (Lt-Con), Lt-SAG, siCTL, siNrf2, or siErbin in EMEM with 90 nM of each siRNA duplex or 40 nM siNrf2 using DharmaFECT transfection reagent (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

ATPlite-based cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 1.5 × 103 cells per well and transfected with scrambled control siRNA or siRNA targeting Nrf2 or Erbin for 48 h. Cell proliferation was analyzed using ATPlite assay (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoblotting and in vivo ubiquitylation assays

IB was performed as described previously (Gu et al., 2007a). The antibodies used were as follows: mouse anti-SAG mAb (Jia et al., 2010), rabbit anti-S6Kα (sc-230), rabbit anti-Rb (sc-050), rabbit anti-IκBα (sc-371), rabbit anti–c-Jun (sc-44), rabbit anti-Nrf2 (sc-722), rabbit anti–cyclin D1 (sc-753), mouse anti–cyclin E (sc-377100), and mouse anti–β-actin (sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.); rabbit anti–phospho-4EBP1 (Ser65; 9451), rabbit anti-4EBP1 (9452), rabbit anti–phospho-S6K (Thr389; 9234), mouse anti-p53 (2524), rabbit anti-AKT (9272), rabbit anti–phospho-AKT (Ser473; 9271), rabbit anti-NOTCH1 (4147), rabbit anti-ATG5 (2630), mouse anti–phospho-IκBα (2859), rabbit anti-p62 (5114), rabbit anti-LC3B (2775), and rabbit anti-DEPTOR (11816; Cell Signaling Technology); mouse anti-p21 (556430) and mouse anti-p27 (554069; BD); mouse anti-NOXA (OP180; EMD Millipore); and rabbit anti–c-Myc (14721; Epitomics). The relative band intensity was quantified using AlphaEaseFC software version 6.0.0 (Alpha Innotech).

The in vivo ubiquitylation assay was performed as described previously (Gu et al., 2007b). In brief, the transfected cells were treated with 10 µM MG132 for 4 h before harvest for in vivo ubiquitination. The cell pellets were lysed by 1 ml of buffer A (6 M guanidine, 10 mM Tris, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 8.0) supplemented with 5 mM imidazole and then were incubated with 50 µl Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen) and rotated overnight at 4°C. Thereafter, the beads were washed once with buffer A supplemented with 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), buffer B (8 M urea, 10 mM Tris, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 8.0) supplemented with 10 mM 2-ME, buffer C (8 M urea, 10 mM Tris, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.3) supplemented with 10 mM 2-ME and 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and, finally, buffer C supplemented with 10 mM 2-ME and 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Bound material was eluted from the beads by suspension in 50 µl of modified sample buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.8% [wt/vol] SDS, 0.1% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.72 M 2-ME, and 300 mM imidazole) followed by boiling for 10 min. The eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blotting for polyubiquitination of Erbin with anti-Erbin antibody.

Ras activity assay

Ras activity was measured by using the RBD of the Ras Activation Assay kit (EMD Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence staining of LC3

LC3 staining was performed as described previously (Xie et al., 2013a, 2014). In brief, cells were fixed with 3.5% formaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked with 0.5% BSA for 15 min. Cells were incubated with rabbit anti-LC3 antibody (1:200) for 2 h followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated donkey anti–rabbit antibody (1:200; Life Technologies) for 1 h. Slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium, and images were taken with 1 × 71 microscope using a 20 × 0.40 NA objective camera (DS-Fi1) and acquisition software NIS-Elements BR 4.00.03. The experiments were performed at a temperature of 25°C. All images were prepared with Photoshop CS2.

Autophagy measurement by fluorescence staining and EM

Autophagic vacuoles were analyzed using a Cyto-ID autophagy detection kit (Enzo Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, cells were stained with Cyto-ID autophagy detection dye and Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) for 20 min at 37°C. Images were taken under the microscope (Nikon). EM analysis of autophagy was performed as described previously (Zhao et al., 2012).

ROS analysis

Cells were stained with 20 µM DCFHDA for 30 min in the dark. For morphological studies, the cells were imaged under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon). For quantifying the ROS levels, the cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD) in FL1 channel (Xie et al., 2011). The mean fluorescence intensity of 10,000 cells was analyzed by WinMDI 2.9 software. The mean fluorescence intensity data were normalized to control levels and expressed as relative fluorescence intensity (2',7'-dichlorofluorescein; Xie et al., 2011).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t test for comparison of two groups or a one-way analysis of variance for comparison of more than two groups followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The statistical analyses were performed using Prism software version 5.01 (GraphPad Software). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. Tumor-free probabilities were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods and were compared between groups using log-rank tests. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study approval

All procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that Sag deletion promoted KrasG12D-induced skin tumor formation. Fig. S2 shows that Sag deletion inhibited autophagy in both keratinocytes and skin tumors. Fig. S3 shows that Sag deletion inhibited senescence in both keratinocytes and skin tumor cells. Fig. S4 shows that Mek inhibitor blocks, whereas H2O2 promotes, autophagy and senescence in keratinocytes. Fig. S5 provides further evidence to show that Erbin is a novel substrate of SAG-βTrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201411104/DC1. Additional data are available in the JCB DataViewer at http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201411104.dv.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. M. Tan and J. Xu in the Sun Laboratory for their help in immunochemical and histological staining.

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grants (CA118762, CA156744, and CA171277) to Y. Sun and by La Ligue Contre le Cancer (Label Ligue) and Institut Paoli-Calmettes grants to J.-P. Borg. J.-P.Borg is a member of Institut Universitaire de France.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- 2-ME

- 2-mercaptoethanol

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- CQ

- chloroquine

- DCFHDA

- 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- DMBA-TPA

- 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene-12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- IB

- immunoblotting

- KO

- knockout

- NAC

- N-acetyl-l-cysteine

- PDZ

- PSD-95/DLG/ZO-1

- RBD

- Ras-binding domain

- RING

- really interesting new gene

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SA-β-gal

- senescence-associated β-galactosidase

- SCF

- SKP1, Cullins, and F-box proteins

References

- Alexander A., Cai S.L., Kim J., Nanez A., Sahin M., MacLean K.H., Inoki K., Guan K.L., Shen J., Person M.D., et al. 2010. ATM signals to TSC2 in the cytoplasm to regulate mTORC1 in response to ROS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:4153–4158. 10.1073/pnas.0913860107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad M.B., Chen Y., and Gibson S.B.. 2009. Regulation of autophagy by reactive oxygen species (ROS): implications for cancer progression and treatment. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11:777–790. 10.1089/ars.2008.2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmain A., and Pragnell I.B.. 1983. Mouse skin carcinomas induced in vivo by chemical carcinogens have a transforming Harvey-ras oncogene. Nature. 303:72–74. 10.1038/303072a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg J.P., Marchetto S., Le Bivic A., Ollendorff V., Jaulin-Bastard F., Saito H., Fournier E., Adélaïde J., Margolis B., and Birnbaum D.. 2000. ERBIN: a basolateral PDZ protein that interacts with the mammalian ERBB2/HER2 receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:407–414. 10.1038/35017038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulin C., Nguyen T., Longley M.A., Zhou Z., Wang X.J., and Roop D.R.. 2004. Inducible activation of oncogenic K-ras results in tumor formation in the oral cavity. Cancer Res. 64:5054–5058. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhry S., Zhang Y., McMahon M., Sutherland C., Cuadrado A., and Hayes J.D.. 2013. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct β-TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene. 32:3765–3781. 10.1038/onc.2012.388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai P., Xiong W.C., and Mei L.. 2006. Erbin inhibits RAF activation by disrupting the sur-8-Ras-Raf complex. J. Biol. Chem. 281:927–933. 10.1074/jbc.M507360200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNicola G.M., Karreth F.A., Humpton T.J., Gopinathan A., Wei C., Frese K., Mangal D., Yu K.H., Yeo C.J., Calhoun E.S., et al. 2011. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 475:106–109. 10.1038/nature10189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies R.J., and Joazeiro C.A.. 2009. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:399–434. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H., Wang Y., Aviram M., Swaroop M., Loo J.A., Bian J., Tian Y., Mueller T., Bisgaier C.L., and Sun Y.. 1999. SAG, a novel zinc RING finger protein that protects cells from apoptosis induced by redox agents. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3145–3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H., Tsvetkov L.M., Liu Y., Song Y., Swaroop M., Wen R., Kung H.F., Zhang H., and Sun Y.. 2001. Promotion of S-phase entry and cell growth under serum starvation by SAG/ROC2/Rbx2/Hrt2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase component: association with inhibition of p27 accumulation. Mol. Carcinog. 30:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einspahr J.G., Bowden G.T., and Alberts D.S.. 2003. Skin cancer chemoprevention: strategies to save our skin. Recent Results Cancer Res. 163:151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa M., and Xiong Y.. 2005. BTB protein Keap1 targets antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 for ubiquitination by the Cullin 3-Roc1 ligase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:162–171. 10.1128/MCB.25.1.162-171.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Bowden G.T., Normolle D., and Sun Y.. 2007a SAG/ROC2 E3 ligase regulates skin carcinogenesis by stage-dependent targeting of c-Jun/AP1 and IκB-α/NF-κB. J. Cell Biol. 178:1009–1023. 10.1083/jcb.200612067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Tan M., and Sun Y.. 2007b SAG/ROC2/Rbx2 is a novel activator protein-1 target that promotes c-Jun degradation and inhibits 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate–induced neoplastic transformation. Cancer Res. 67:3616–3625. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart M., Concordet J.P., Lassot I., Albert I., del los Santos R., Durand H., Perret C., Rubinfeld B., Margottin F., Benarous R., and Polakis P.. 1999. The F-box protein β-TrCP associates with phosphorylated β-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr. Biol. 9:207–210. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80091-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Gu Q., Zheng M., Normolle D., and Sun Y.. 2008. SAG/ROC2/RBX2 E3 ligase promotes UVB-induced skin hyperplasia, but not skin tumors, by simultaneously targeting c-Jun/AP-1 and p27. Carcinogenesis. 29:858–865. 10.1093/carcin/bgn021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani S.R., Petricoin E.F., Maitra A., Rajapakse V., King C., Jacobetz M.A., Ross S., Conrads T.P., Veenstra T.D., Hitt B.A., et al. 2003. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 4:437–450. 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00309-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.Z., Zang M., Xiong W.C., Luo Z., and Mei L.. 2003. Erbin suppresses the MAP kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1108–1114. 10.1074/jbc.M205413200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaulin-Bastard F., Saito H., Le Bivic A., Ollendorff V., Marchetto S., Birnbaum D., and Borg J.P.. 2001. The ERBB2/HER2 receptor differentially interacts with ERBIN and PICK1 PSD-95/DLG/ZO-1 domain proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276:15256–15263. 10.1074/jbc.M010032200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., and Sun Y.. 2011. SCF E3 ubiquitin ligases as anticancer targets. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 11:347–356. 10.2174/156800911794519734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., Yang J., Hao X., Zheng M., He H., Xiong X., Xu L., and Sun Y.. 2010. Validation of SAG/RBX2/ROC2 E3 ubiquitin ligase as an anticancer and radiosensitizing target. Clin. Cancer Res. 16:814–824. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., Li H., and Sun Y.. 2011. Induction of p21-dependent senescence by an NAE inhibitor, MLN4924, as a mechanism of growth suppression. Neoplasia. 13:561–569. 10.1593/neo.11420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T., Maenaka K., Kotoshiba S., Matsumoto M., Kohda D., Conaway R.C., Conaway J.W., and Nakayama K.I.. 2004. VHL-box and SOCS-box domains determine binding specificity for Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules of ubiquitin ligases. Genes Dev. 18:3055–3065. 10.1101/gad.1252404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensler T.W., Wakabayashi N., and Biswal S.. 2007. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47:89–116. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M., Hatakeyama S., Shirane M., Matsumoto M., Ishida N., Hattori K., Nakamichi I., Kikuchi A., Nakayama K., and Nakayama K.. 1999. An F-box protein, FWD1, mediates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of β-catenin. EMBO J. 18:2401–2410. 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolch W. 2003. Erbin: sorting out ErbB2 receptors or giving Ras a break? Sci. STKE. 2003:pe37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong B., Qia C., Erkan M., Kleeff J., and Michalski C.W.. 2013. Overview on how oncogenic Kras promotes pancreatic carcinogenesis by inducing low intracellular ROS levels. Front Physiol. 4:246 10.3389/fphys.2013.00246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapouge G., Youssef K.K., Vokaer B., Achouri Y., Michaux C., Sotiropoulou P.A., and Blanpain C.. 2011. Identifying the cellular origin of squamous skin tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:7431–7436. 10.1073/pnas.1012720108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.C., Fenster B.E., Ito H., Takeda K., Bae N.S., Hirai T., Yu Z.X., Ferrans V.J., Howard B.H., and Finkel T.. 1999. Ras proteins induce senescence by altering the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 274:7936–7940. 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Tan M., Jia L., Wei D., Zhao Y., Chen G., Xu J., Zhao L., Thomas D., Beer D.G., and Sun Y.. 2014. Inactivation of SAG/RBX2 E3 ubiquitin ligase suppresses KrasG12D-driven lung tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 124:835–846. 10.1172/JCI70297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichti U., Anders J., and Yuspa S.H.. 2008. Isolation and short-term culture of primary keratinocytes, hair follicle populations and dermal cells from newborn mice and keratinocytes from adult mice for in vitro analysis and for grafting to immunodeficient mice. Nat. Protoc. 3:799–810. 10.1038/nprot.2008.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lluis J.M., Buricchi F., Chiarugi P., Morales A., and Fernandez-Checa J.C.. 2007. Dual role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in hypoxia signaling: activation of nuclear factor-κB via c-SRC– and oxidant-dependent cell death. Cancer Res. 67:7368–7377. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P.K., Grüner B.M., Nakhai H., Sipos B., Zimber-Strobl U., Strobl L.J., Radtke F., Schmid R.M., and Siveke J.T.. 2010. Identification of epidermal Pdx1 expression discloses different roles of Notch1 and Notch2 in murine KrasG12D-induced skin carcinogenesis in vivo. PLoS ONE. 5:e13578 10.1371/journal.pone.0013578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon E.J., Sonveaux P., Porporato P.E., Danhier P., Gallez B., Batinic-Haberle I., Nien Y.C., Schroeder T., and Dewhirst M.W.. 2010. NADPH oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species production activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) via the ERK pathway after hyperthermia treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:20477–20482. 10.1073/pnas.1006646107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K.I., and Nakayama K.. 2006. Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6:369–381. 10.1038/nrc1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson T.R., Laplante M., Thoreen C.C., Sancak Y., Kang S.A., Kuehl W.M., Gray N.S., and Sabatini D.M.. 2009. DEPTOR is an mTOR inhibitor frequently overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells and required for their survival. Cell. 137:873–886. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M., Zhou H., Fan S., Li Z., Yao G., Tashiro S., Onodera S., Xia M., and Ikejima T.. 2013. mTOR inactivation by ROS-JNK-p53 pathway plays an essential role in psedolaric acid B induced autophagy-dependent senescence in murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 715:76–88. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada P., Rojo A.I., Chowdhry S., McMahon M., Hayes J.D., and Cuadrado A.. 2011. SCF/β-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31:1121–1133. 10.1128/MCB.01204-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada P., Rojo A.I., Evrard-Todeschi N., Innamorato N.G., Cotte A., Jaworski T., Tobón-Velasco J.C., Devijver H., García-Mayoral M.F., Van Leuven F., et al. 2012. Structural and functional characterization of Nrf2 degradation by the glycogen synthase kinase 3/β-TrCP axis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:3486–3499. 10.1128/MCB.00180-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman I., Lowry D.T., Adams C., Abdel-Fattah R., Holly A., Yuspa S.H., and Hennings H.. 2000. Frequent codon 12 Ki-ras mutations in mouse skin tumors initiated by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine and promoted by mezerein. Mol. Carcinog. 27:298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier F., and Campisi J.. 2011. Four faces of cellular senescence. J. Cell Biol. 192:547–556. 10.1083/jcb.201009094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh H., Moriguchi T., Takai J., Ebina M., and Yamamoto M.. 2013. Nrf2 prevents initiation but accelerates progression through the Kras signaling pathway during lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 73:4158–4168. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M., Lin A.W., McCurrach M.E., Beach D., and Lowe S.W.. 1997. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 88:593–602. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81902-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy T.A., Smith P.G., Milhollen M.A., Berger A.J., Gavin J.M., Adhikari S., Brownell J.E., Burke K.E., Cardin D.P., Critchley S., et al. 2009. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature. 458:732–736. 10.1038/nature07884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J.M., Kahn S.M., Jiang W., DeLeo V.A., and Weinstein I.B.. 1995. Activated ras genes occur in human actinic keratoses, premalignant precursors to squamous cell carcinomas. Arch. Dermatol. 131:796–800. 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690190048009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., and Li H.. 2013. Functional characterization of SAG/RBX2/ROC2/RNF7, an antioxidant protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Protein Cell. 4:103–116. 10.1007/s13238-012-2105-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Tan M., Duan H., and Swaroop M.. 2001. SAG/ROC/Rbx/Hrt, a zinc RING finger gene family: molecular cloning, biochemical properties, and biological functions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 3:635–650. 10.1089/15230860152542989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaroop M., Wang Y., Miller P., Duan H., Jatkoe T., Madore S.J., and Sun Y.. 2000. Yeast homolog of human SAG/ROC2/Rbx2/Hrt2 is essential for cell growth, but not for germination: chip profiling implicates its role in cell cycle regulation. Oncogene. 19:2855–2866. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Gallegos J.R., Gu Q., Huang Y., Li J., Jin Y., Lu H., and Sun Y.. 2006. SAG/ROC-SCFβ-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase promotes pro-caspase-3 degradation as a mechanism of apoptosis protection. Neoplasia. 8:1042–1054. 10.1593/neo.06568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Gu Q., He H., Pamarthy D., Semenza G.L., and Sun Y.. 2008. SAG/ROC2/RBX2 is a HIF-1 target gene that promotes HIF-1α ubiquitination and degradation. Oncogene. 27:1404–1411. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Davis S.W., Saunders T.L., Zhu Y., and Sun Y.. 2009. RBX1/ROC1 disruption results in early embryonic lethality due to proliferation failure, partially rescued by simultaneous loss of p27. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:6203–6208. 10.1073/pnas.0812425106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Zhu Y., Kovacev J., Zhao Y., Pan Z.Q., Spitz D.R., and Sun Y.. 2010. Disruption of Sag/Rbx2/Roc2 induces radiosensitization by increasing ROS levels and blocking NF-κB activation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49:976–983. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Li Y., Yang R., Xi N., and Sun Y.. 2011a Inactivation of SAG E3 ubiquitin ligase blocks embryonic stem cell differentiation and sensitizes leukemia cells to retinoid acid. PLoS ONE. 6:e27726 10.1371/journal.pone.0027726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Zhao Y., Kim S.J., Liu M., Jia L., Saunders T.L., Zhu Y., and Sun Y.. 2011b SAG/RBX2/ROC2 E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for vascular and neural development by targeting NF1 for degradation. Dev. Cell. 21:1062–1076. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Li H., and Sun Y.. 2014. Endothelial deletion of Sag/Rbx2/Roc2 E3 ubiquitin ligase causes embryonic lethality and blocks tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene. 33:5211–5220. 10.1038/onc.2013.473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Dai P., Liu Y., Marchetto S., Xiong W.C., Borg J.P., and Mei L.. 2009. Erbin regulates NRG1 signaling and myelination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:9477–9482. 10.1073/pnas.0901844106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Shen C., Luo S., Traoré W., Marchetto S., Santoni M.J., Xu L., Wu B., Shi C., Mei J., et al. 2014. Role of Erbin in ErbB2-dependent breast tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:E4429–E4438. 10.1073/pnas.1407139111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale-Cross L., Amornphimoltham P., Fisher G., Molinolo A.A., and Gutkind J.S.. 2004. Conditional expression of K-ras in an epithelial compartment that includes the stem cells is sufficient to promote squamous cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 64:8804–8807. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D., and Sun Y.. 2010. Small RING finger proteins RBX1 and RBX2 of SCF E3 ubiquitin ligases: the role in cancer and as cancer targets. Genes Cancer. 1:700–707. 10.1177/1947601910382776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C.M., Chan W.Y., Yu S., Zhao J., and Cheng C.H.. 2011. Bufalin induces autophagy-mediated cell death in human colon cancer cells through reactive oxygen species generation and JNK activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51:1365–1375. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C.M., Liu X.Y., Yu S., and Cheng C.H.. 2013a Cardiac glycosides block cancer growth through HIF-1α- and NF-κB-mediated Plk1. Carcinogenesis. 34:1870–1880. 10.1093/carcin/bgt136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C.M., Wei W., and Sun Y.. 2013b Role of SKP1-CUL1-F-box-protein (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligases in skin cancer. J. Genet. Genomics. 40:97–106. 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C.M., Liu X.Y., Sham K.W., Lai J.M., and Cheng C.H.. 2014. Silencing of EEF2K (eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase) reveals AMPK-ULK1-dependent autophagy in colon cancer cells. Autophagy. 10:1495–1508. 10.4161/auto.29164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., McEachern D., Li W., Davis M.A., Li H., Morgan M.A., Bai L., Sebolt J.T., Sun H., Lawrence T.S., et al. 2011. Radiosensitization of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by a SMAC-mimetic compound, SM-164, requires activation of caspases. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10:658–669. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., and Rape M.. 2009. Building ubiquitin chains: E2 enzymes at work. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:755–764. 10.1038/nrm2780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A.R., and Narita M.. 2010. Connecting autophagy to senescence in pathophysiology. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22:234–240. 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A.R., Narita M., Ferreira M., Kirschner K., Sadaie M., Darot J.F., Tavaré S., Arakawa S., Shimizu S., Watt F.M., and Narita M.. 2009. Autophagy mediates the mitotic senescence transition. Genes Dev. 23:798–803. 10.1101/gad.519709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamkova M., Khromova N., Kopnin B.P., and Kopnin P.. 2013. Ras-induced ROS upregulation affecting cell proliferation is connected with cell type-specific alterations of HSF1/SESN3/p21Cip1/WAF1 pathways. Cell Cycle. 12:826–836. 10.4161/cc.23723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Xiong X., Jia L., and Sun Y.. 2012. Targeting Cullin-RING ligases by MLN4924 induces autophagy via modulating the HIF1-REDD1-TSC1-mTORC1-DEPTOR axis. Cell Death Dis. 3:e386 10.1038/cddis.2012.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.