Abstract

Though great progress has been realized over the last decade in extending HIV prevention, care and treatment in some of the least resourced settings of the world, a substantial gap remains between what we know works and what we are actually achieving in HIV programs. To address this, leaders have called for the adoption of an implementation science framework to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of HIV programs. Implementation science (IS) is a multidisciplinary scientific field that seeks generalizable knowledge about the magnitude of, determinants of and strategies to close the gap between evidence and routine practice for health in real-world settings. We propose an IS approach that is iterative in nature and composed of four major components: 1) Identifying Bottlenecks and Gaps, 2) Developing and Implementing Strategies, 3) Measuring Effectiveness and Efficiency, and 4) Utilizing Results. With this framework, IS initiatives draw from a variety of disciplines including qualitative and quantitative methodologies in order to develop new approaches responsive to the complexities of real world program delivery. In order to remain useful for the changing programmatic landscape, IS research should factor in relevant timeframes and engage the multi-sectoral community of stakeholders, including community members, health care teams, program managers, researchers and policy makers, to facilitate the development of programs, practices and polices that lead to a more effective and efficient global AIDS response. The approach presented here is a synthesis of approaches and is a useful model to address IS-related questions for HIV prevention, care and treatment programs. This approach, however, is not a panacea, and we will continue to learn new ways of thinking as we move forward to close the implementation gap.

Keywords: AIDS, antiretroviral therapy, HIV, HIV Prevention, HIV treatment, implementation science, key populations, methadone.

INTRODUCTION

The global AIDS response has realized great progress in extending HIV prevention, care and treatment in some of the least resourced settings in the world. However with current economic conditions, funding for HIV has leveled, and resources struggle to keep up with health care need. The 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines have increased demand for HIV services, and we face increasing pressure to confront other healthcare needs in addition to HIV. These realities require a strengthened and improved global AIDS response.

Over the last several years, leaders in the field of HIV have called for the adoption of an implementation science (IS) approach to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of HIV programs [1–4]. With the new 2013 WHO guidelines, recent estimates in low- and middle-income countries indicate that 37% of people who are eligible for treatmentare receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), 56% of HIV-infected women are receiving the medications necessary to prevent HIV transmission to their children, 35% of children born to mothers living with HIV received an HIV test within the first 2 months of life, 42% used condoms at their last high risk sexual encounter and 8% of opioid addicts are receiving opioid substitution therapy [5 – 7]. In the United States, only 25% of the 1.1 million people living with HIV are virally suppressed [3]. These statistics highlight a critical implementation gap - the gap between what we know works and what we are actually achieving in HIV prevention, care and treatment programs. In moving from study to real-world environments, the delivery of interventions in service delivery settings is quickly met with the complexities of culture, economics, behavior, gender, social circumstances, and political environment that must be adequately considered in order to optimize utilization and continued engagement of services by clients.

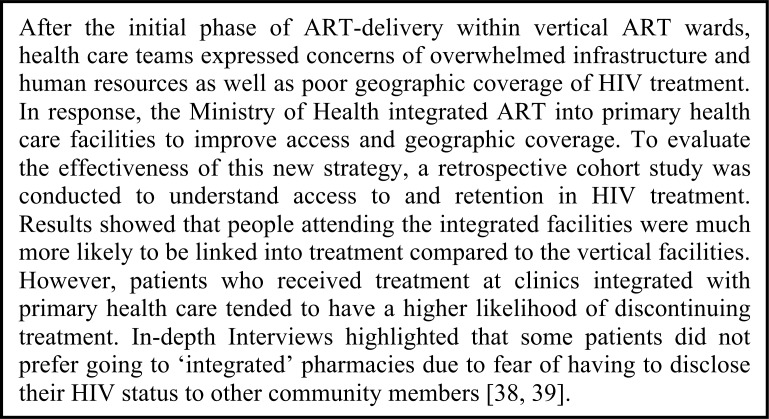

Implementation science (IS) is ‘a multidisciplinary scientific field that seeks generalizable knowledge about the magnitude of, determinants of and strategies to close the gap between evidence and routine practice for health in real-world settings’ [8]. In doing so, IS draws from a variety of different research disciplines including epidemiology, biostatistics, anthropology, sociology, health policy, health economics, management sciences, mathematical modeling, community engagement and ethics. Using these methodologies with HIV programs, IS identifies, develops and measures the impact of innovative strategies to improve service delivery, contributing to the basis for evidence-informed programming and thereby strengthening the global AIDS response [9]. In this paper, we propose an IS approach for HIV programs that integrates the perspective of these disciplines and synthesizes a number of approaches [1, 10-12]. This iterative approach is comprised of four major components: 1) Identifying Bottlenecks and Gaps, 2) Developing and Implementing Strategies, 3) Measuring the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Strategies and 4) Utilizing Results (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

An implementation science approach for HIV programs.

When addressing the multi-faceted nature of IS questions, perspectives from a variety of stakeholders and individuals at different stages in the process are needed. This is a theme throughout the IS approach. Meaningful engagement of the community of stakeholders whereby community members, health care teams, program managers, researchers and policy-makers are involved in each of the components will increase the likelihood that new approaches will be successful, sustainable and scalable in reducing the implementation gap [13-16]. By engaging stakeholders from the outset, community engagement approaches can facilitate the development of programs, practices and policies that lead to a more effective and efficient global AIDS response.

IDENTIFYING BOTTLENECKS & GAPS

To begin addressing IS questions, a clear understanding of the gaps in HIV programs must be developed. Establishing and strengthening monitoring and evaluation (M&E) and surveillance systems that facilitate identification of missed opportunities in program delivery are critical. Effective delivery of HIV prevention, care and treatment requires multiple interactions of clients with community-based and clinic-based services, and therefore, programs must be able to assess the flow of patients through and between delivery systems.

For example, patients flow through a series of steps from HIV testing into HIV treatment, often referred to as the treatment ‘cascade’ due to the staggering losses to follow-up between different steps. Recent systematic reviews suggest that 59% of those diagnosed with HIV are assessed for ART eligibility; 68% of those eligible actually initiate ART while 46% of those not eligible are retained in care; and 70% of those who initiate ART are retained 2 years after treatment initiation [17-18]. In light of this, routine M&E indicators that enable tracking of the various cascades (i.e., HIV testing to treatment for children and adults, prevention of mother to child transmission, linkage and retention into opiate substitution treatment) within programs should be prioritized (Box 1). Designing and tracking the right indicators for a particular program’s objectives is critical for an effective understanding of current gaps.

Box (1).

Case study: HIV treatment cascade in China.

Understanding where bottlenecks exist is the first step in uncovering why there is a gap between observed and intended HIV program outcomes. To begin identifying factors potentially connected with variability between clinics, communities or risk groups, a variety of different types of research can be used, including observational epidemiology designs [20,21]. Patient flow mapping, human resource analyses, causal diagrams or Ishikawa diagrams can be useful thought exercises to understand what factors could be leading to the observed gaps [21-23]. In addition, theoretical frameworks, such as Predis-posing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation (PRECEDE) [24], Diffusion of Innovations [25] or the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [26], are helpful to understand a particular implementation gap, guide the development of new implementation strategies and facilitate an understanding of barriers that threaten sustained large-scale public prevention and treatment programs over time.

Concurrently, qualitative methodologies including in-depth interviews and focus group discussions can be pivotal in gaining an understanding of why certain gaps exist. Engaging health care teams as well as intended service beneficiaries is critical in this process. Community-engagement whereby program managers, clinicians, pharmacists, laboratory technicians, community outreach workers, current patients or community members are involved can all yield essential insights into what problems programs face and why they are occurring.

DEVELOPING AND IMPLEMENTING STRATEGIES

Effective adaptation and uptake of evidence into practice occurs via relationships and activities between communities (groups of individuals, such as physicians, patients or community members), delivery systems (community-based organizations, hospitals or primary health care clinics that facilitate the delivery of health services) and health interventions (i.e., condoms, diagnostics, antiretroviral therapy, methadone, etc.) [11]. One of the fundamental aspects of IS initiatives is deciding where change(s) must be targeted among the components of this system and what are the best approaches for inducing change, be it at the organizational, social or individual level. In formulating new approaches, teams should consider the context of the linkages, interactions, relationships and behaviors of the components of the system of health care under investigation [28], and consider approaches that can be translated to other settings, allowing for local adaptation as appropriate.

Continuing community engagement at this stage will be another fundamental aspect of developing innovative strategies that effectively factor in both culture and context. Communities, especially members who would implement the strategies and clients who would access the services, must become active partners in the refinement and improvement of implementation strategies so that we capture the ‘on-the-ground’ experience. It is of paramount importance to build HIV programs that are responsive to the communities that interact with them (Box 3).

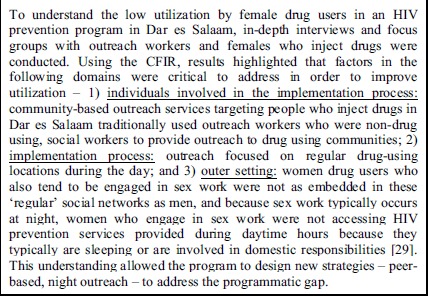

Box (3).

Case study: HIV prevention in Dar es Salaam.

In tandem, continuing the use of theoretical frameworks, mentioned above, can be particularly useful for policy makers, program managers and researchers in understanding a particular implementation gap as well as to guide the development and consideration of new implementation strategies. These frameworks consider a variety of factors that need to be addressed for successful implementation. For example, the PRECEDE approach, which has been validated in diverse settings, organizes factors into three main constructs – 1) predisposing factors: composed of knowledge, attitudes, social norms and sense of self-efficacy that affect behavior, 2) enabling factors: characteristics that facilitate behavior change such as availability and accessibility of services or resources and 3) reinforcing factors: characteristics such as social support, social norms or economic incentives that reward the desired change [24, 30]. Box 4 illustrates its use in Tanzania. The development of improved strategies should utilize these frameworks, thereby leveraging decades of experience with health program planning development, and consider the proper modalities for knowledge transfer and support to facilitate their adoption.

Box (4).

Case study: methadone treatment in Tanzania.

MEASURING EFFECTIVENESS AND EFFICIENCY

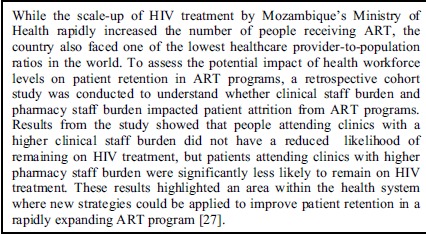

A variety of study designs to evaluate the impact of implementation strategies exist including non-randomized and randomized approaches. Each study has a unique set of characteristics - study population, latency of effects, selection bias, outcome measurement, confounding, effect modification, secular trends, analytical method and assumptions, etc. – that have to be carefully considered when weighing the strengths and weaknesses of different designs for a given question. Table 1 outlines the features for several types of studies that can be used with certain implementation, service and client outcomes [31,32]. An extensive overview of different designs is beyond the scope of this paper; Shadish and colleagues provide a more comprehensive discussion of the strengths, limitations, biases and supplementary approaches for different designs [31]. At this stage, engaging researchers who have experience in developing studies to answer IS-related questions will be critical to consider the many characteristics in designing appropriate evaluations.

Table 1.

Study designs for implementation science.

| Study Design | Key Study Features* | Basis for Estimating Effect of Implementation Strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What Happened? | What Would Have Happened?ϕ | ||

| Pre-post§ | Implementation strategy is implemented in a group of study participants. Outcomes are measured before and after the implementation. | Outcome change over time | No outcome change |

| Post-only with concurrent controls§¥ | Implementation strategy is implemented in a group and not implemented in a separate group of study participants. Outcomes are measured on exposed and unexposed study participants after implementation. | Outcomes in exposed group | Outcomes in non-exposed group |

| Pre-post with concurrent controls§¥ | Implementation strategy is implemented in a group and not implemented in a separate group of study participants. Outcomes are measured on exposed and unexposed study participants before and after implementation. | Outcome change over time in exposed group | Outcome change over time in non-exposed group |

| Interrupted time series | A large series of consecutive outcome observations on study participants is interrupted by the implementation of the strategy. | Change in level or slope of outcome | Continuation of prior time trend of outcome |

| Interrupted time series with concurrent controls¥ | A large series of consecutive outcome observations on study participants is interrupted by the implementation of a strategy for the exposed group and is not interrupted for the non-exposed group | Change in level or slope of outcome in exposed group | Change in level or slope of outcome in non-exposed group |

| Regression Discontinuity Design§ | The implementation strategy is assigned to exposed and non-exposed groups based on their need, as defined by a cutoff score of a pre-determined assignment variable. Outcomes are measured after implementation. | Regression line in exposed group | Regression line in unexposed group |

| Stepped-wedge¥ | The implementation strategy is phased in over time to groups of study participants, and outcomes are measured on exposed and unexposed study participants at multiple points in time before and after the intervention. | Outcomes in groups receiving exposure | Outcomes in groups not receiving exposure |

*Study participants can be individuals or groups (i.e., clinics); §-can be extended to include more outcome measurements over time; ¥-randomization to exposed/non-exposed groups possible; ϕ-This is often referred to as the counterfactual and serves as the comparison to understand if the implementation strategy affected study outcomes.

We agree with Padian and colleagues that ‘we should not aim for the second best as our first choice’ in choosing a design for a given study question [33]. Due to their ability to equalize groups under comparison, randomized experimental designs of individuals or groups are regarded as the ‘gold standard’ of study designs in estimating the causal effects of approaches on predetermined outcomes. However, randomized designs are often criticized for lacking generalizability due to strict inclusion criteria used for study participants [34-36] and often take long timeframes to complete. We would also like to emphasize that many non-randomized designs have been used to make major conclusions about causality with regards to preventing disease (i.e., not sharing needles for injections prevents HIV, not smoking prevents cancer), preventing adverse effects of therapy (i.e., toxicities of stavudine) and the benefits of certain types of interventions (i.e., condom use prevents HIV, methadone prevents the acquisition of HIV). Non-randomized designs will also be important and allow, in certain contexts, conclusions to be made about causality in the context of IS research. The choice of an appropriate study design will have to balance the desire for ‘gold standard’ designs and the need for making programmatic and policy decisions within relevant, and often short, timeframes.

Qualitative methodologies can be utilized to clarify the plausible pathways between the intervention and study outcomes and elucidate our understanding of why a particular approach did or did not work (Box 5). Theoretical frameworks, mentioned in earlier stages, can inform which implementation outcomes are appropriate to advance our understanding of the implementation process, leading to an improved understanding of the contextual factors, such as internal and external environment, provider attitudes and site characteristics, that can explain why an approach did or did not work and whether the approach is appropriate for other settings [32].

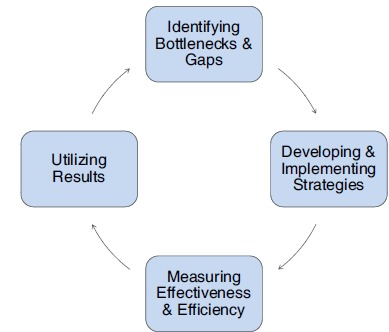

Box (5).

Case study: HIV treatment integration in Mozambique.

In addition to understanding effectiveness of implementation strategies, identifying efficient, cost-effective implementation models for proven interventions are also needed to build an improved and more sustainable global AIDS response. Cost-effectiveness analyses are needed to understand the relative efficiency of different approaches by measuring and comparing the costs and consequences of different strategies. Analyses of costs provide a transparent guide that enables program managers and planners to make informed decisions about resource allocation designed to maximize health benefit per programdollar [37]. In order to sustain large-scale, public prevention and treatment programs, economic analysis will be particularly salient as progress in access to and quality of interventions for HIV prevention, care and treatment confronts funding limits.

UTILIZING RESULTS

The ultimate success of IS initiatives is when research findings are appropriately used to improve programs and tailor policies when lessons have been learned. Using this approach, results from the assessment of whether new implementation approaches improve service delivery will provide new information for decision-makers. In some cases, the new strategy will not have worked as intended, and the focus will return to developing new approaches. In other cases, the approach might have worked, and consideration for how to utilize the information will depend on the scope of the study (i.e., pilot, large-scale trial, etc.) as well as results from similar initiatives in different settings.

Many initiatives to improve the quality of health care delivery have failed to translate from a research setting to a more broad application because key players who are essential for the translation process are not included in the process [10,11]. As discussed above, engaging the relevant health communities from the outset, where ‘community’ is defined broadly to include ministries of health, policy makers, program implementers (health systems and community based organizations), researchers, advocates or community-members, will be critical to disseminate and use results more broadly [11]. This will require expertise in developing partnerships and consortiums with individuals and organizations that have a range of different interests and proficiencies. Doing so will increase the likelihood that a strategy, if effective, will be incorporated and applied more broadly to inform scale-up.

Another critical way to utilize results is to share them with the larger, global HIV/AIDS community. Those interested in results from IS initiatives will likely include a range of individuals including service users, academic researchers, providers, managers, administrators and policy makers. A clear dissemination strategy can facilitate the use of appropriate communication channels for different audience members with the most pertinent information to their needs [10]. Furthermore, efforts to combine findings from independent studies into meta-analyses will be essential to understand whether particular strategies are robust across different contexts, and if not, what factors explain the heterogeneity of results [21].

CONCLUSION

The approach presented here is a synthesis of approaches and is a useful model to address IS-related questions for HIV prevention, care and treatment programs. Our approach emphasizes the necessity of utilizing a variety of research methodologies, as each will be critical at different points in the process. Additionally, engaging communities from the outset will be paramount to ensure that newly developed strategies are appropriate to the context and potentially scalable to other settings. Appropriate study designs for IS-related initiatives will be determined by many factors, often not in control of the investigator, and a variety of approaches should be encouraged to ensure that we do not marginalize certain implementation strategies. Ultimately, the results of IS projects must be incorporated into programming as lessons are learned and disseminated more broadly to the larger global AIDS community. Partnerships between program implementers, policy makers, researchers and community members will also need to develop in order to effectively drive the IS agenda. This approach, however, is not a panacea. Health program delivery exists in complex environments, and we will undoubtedly continue to learn new ways of thinking as we move forward in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the global AIDS response.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Box (2).

Case study: human resource shortages and HIV treatment in Mozambique.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors declare that they have no competing interests and contributed substantially to the manuscript. More specifically, BL, BC, TP, IU, TA, JM, AC, MD, EG and PV assisted in drafting the manuscript. BL and PV developed the original concept and approach. BL, BC, MD and IU developed the community engagement and qualitative approaches section. BL, TP, TA, IU, and JM contributed to the real-world case studies. BL, AC and EG contributed to the discussion regarding theoretical frameworks and study design. The authors would like to thank Judy Auerbach for her review and comments on the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AIDS =

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- ART =

Antiretroviral Therapy

- CD4 =

Cluster of Differentiation 4

- CFIR =

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- HIV =

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IS =

Implementation Science

- M & E =

Monitoring and Evaluation

- PRECEDE =

Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs for Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation

- WHO =

World Health Organization

REFERENCES

- 1.Padian NS, Holmes CB, McCoy SI, Lyerla R, Bouey PD, Goosby EP. Implementation science for the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. Mar. 2011;56(3):199–203. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bb448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirschhorn LR, Ojikutu B, Rodriguez W. Research for change using implementation research to strengthen HIV care and treatment scale-up in resource-limited settings. The Journal of Infectious Diseases Dec 1. 2007;196 (Suppl):S516–22. doi: 10.1086/521120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC Global HIV/AIDS Implementation Science. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/globalaids/What-CDC-is-Doing/implementation-science.html . 2010. [Accessed 1 July 2013].

- 4.CDC USAID's Implementation Science Investment Improving HIV/AIDS Programming through the Translation of Research to Practice. Available from http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/fact-sheets/usaids-implementation-science-investment . 2012. [Accessed 12 July 2013].

- 5.WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF Global HIV/AIDS Response, Progress Report 2011. Available from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/en/index.html . 2011. [Accessed 11 July 2013.].

- 6.Needle R, Fu J, Beyrer C , et al. PEPFAR's evolving HIV prevention approaches for key populations--people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and sex workers progress, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes Aug 15. 2012;15( Suppl 3):E154–E164. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825f315e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS Global Update on HIV Treatment 2013: Results, Impact and Opportunities. Available from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85326/1/9789241505734_eng.pdf.p1-126 . 2013. [Accessed 1 September 2013].

- 8.Odeny TA, Geng E. Defining Implementation Science to Inform Future ARV Guidelines 3rd Global WHO Consultation on Strategic Use of ARVs; February 2014; Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartländer B, Stover J, Hallett T, et al. Towards an improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. Jun 11. 2011;377(9782):2031–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60702-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher AA, Foreit Jr, Laing J. Designing HIV/AIDS Intervention Studies. Available from http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/horizons/orhivaidshndbk.pdf. 2002. [Accessed 28 September 2013].

- 11.Gonzales R, Handley MA, Ackerman S, O'sullivan PS. A frame-work for training health professionals in implementation and dissemination science. [Mar];Academic Medicine Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2012 87(3):271–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182449d33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. An Approach to Rapid Scale-up Using HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care as an Example. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/en/rapidscale_up. pdf . 2004. [ Accessed 17 July 2013]. pp. 1–20.

- 13.Brown L, Tandon R. Ideology and Political Economy in Inquiry Action Research and Participatory Research. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 1983;1(2):277–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.ML S, editor. The Sage Handbook of Action Research Participative Inquiry and Practice. 2008. Participatory Action Research as Practice. pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2):ii3–12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung MW, Yen IH, Minkler M. Community based participatory research a promising approach for increasing epidemiology's relevance in the 21st century. International Journal of Epidemiology. Jun. 2004;33(3):499–506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa a systematic review. PLOS Medicine. Jul. 2011;8(7):e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007-2009: systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health. Jun. 2010;15( Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambdin BH, Cai T, Udoh I, et al. Identifying Bottlenecks Loss to follow-up of MSM from HIV Testing to Treatment in Wuhan, China International AIDS Conference; 2012; Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss NS. Clinical Epidemiology The study of the outcome of illness (Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics). OUP USA. 2006:188. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Modern Epidemiology. p. 758. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa K. Guide to quality control. Asian Productivity Organization. 1986:226. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagopian A, Micek MA, Vio F, Gimbel-Sherr K, Montoya P. What if we Decided to Take Care of Everyone Who Needed Treatment? Workforce Planning in Mozambique Using Simulation of Demand for HIV/AIDS Care. Hum Resour Health. Feb. 2008;7(6 ):3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green LW, Krueter M. Health Program Planning-An Educational and Ecological Approach. journal name. 2005:1–458. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salwen M, Stacks D, Mahwah NJ, Rogers EM, Singhal A. Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed) An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research. (Fifth edition) 2003:409–419. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implemetnation of health services research findings into pracitce a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambdin BH, Micek MA, Koepsell TD, et al. Patient volume, human resource levels, and attrition from HIV treatment programs in central Mozambique. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:e33–e39. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182167e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Available from http://www.who.int/allian ce-hpsr/resources/9789241563895/en/index.html . 2009. [Accessed 19 July 2013].

- 29.Lambdin BH, Bruce RD, Chang O, et al. Identifying Programmatic Gaps Inequities in Harm Reduction Service Utilization among Male and Female Drug Users in Dar es Salaam Tanzania. PLOS ONE. Ja. 2013;8(6):e67062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langlois MA, Hallam JS. Integrating multiple health behavior theories into program planning the PER worksheet. Health Promotion Practice. Mar. 2010;11(2):282–8. doi: 10.1177/1524839908317668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shadish WR, Cook TD. Campbell, DT. Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs for Generalised Causal Inference. Houghton Mifflin. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for Implementation Research Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padian NS, Holmes CB, McCoy SI, et al. Response to Letter from Thomas et al Critiquing “ Implementation science for the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief”. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. Mar. 2011;58(1 ):e21–22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bb448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gandhi M, Ameli N, Bacchetti P et al. Eligibility criteria for HIV clinical trials and generalizability of results the gap between published reports and study protocols. AIDS. Nov. 2005;4(16 ):1885–96. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000189866.67182.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frangakis C. The calibration of treatment effects from clinical trials to target populations. Clinical Trials. Apr. 2009;6(2):136–40. doi: 10.1177/1740774509103868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenhouse JB, Kaizar EE, Kelleher K, Seltman H, Gardner W. Generalizing from clinical trial data a case study. The risk of suicidality among pediatric antidepressant users. [May 20]; Statistics in Medicine. 2008 27(11):1801–13. doi: 10.1002/sim.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UNAIDS. Cost-effectiveness analysis and HIV/AIDS. Available from http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/publications/irc-pub03/costtu_en.pdf. 1998. [Accessed 13 July 2013].

- 38.Lambdin BH, Micek MA, Sherr K , et al. Integration of HIV care and treatment in primary health care centers and patient retention in central Mozambique a retrospective cohort study. [2013 Apr 15];Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 62(5):e146–52. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182840d4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfeiffer J, Montoya P, Baptista AJ , et al. Integration of HIV/AIDS services into African primary health care lessons learned for health system strengthening in Mozambique - a case study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. Jan. 2010;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]