Abstract

We report on the first polypharmacy adherence monitoring over 371 days, integrated into a pharmaceutical care service (counselling, electronic multidrug punch cards, feedback on recent electronic records) for a 65-year-old man with diabetes after hospital discharge. The initial daily regimen of four times per day with 15 pills daily changed after 79 days into a daily regimen of two times per day with 9 pills daily for the next 292 days. The patient removed all medication from the multidrug punch cards (taking adherence 100%) and had 96.9% correct dosing intervals (timing adherence). The 57 evening doses showed the least variation in intake times at 17 h 45 min±8 min. Over the observation year, the patient was clinically stable. He was very satisfied with the multidrug punch card and the feedback on electronic records. In conclusion, long-term monitoring of polypharmacy was associated with the benefit of successful disease management.

Background

According to its latest definition, “Pharmaceutical Care is the pharmacist’s contribution to the care of individuals in order to optimise medicines use and improve health outcomes”.1 Thus, medication adherence, that is, the extent to which a patient follows the recommendations by a healthcare professional, represents a central concern in pharmacy practice. With typical adherence rates for oral prescription medication of approximately 50–76%,2 3 non-adherence has been designated as one of the largest healthcare problems in society,3–5 since it impairs clinical outcomes and quality of life and generates costs.6–10 Polypharmacy, that is, the use of multiple drugs administered to the same patient,11 has been described as a factor strongly related to non-adherence.12 13 However, polypharmacy has become common because of, for example, clinical practice relying on multidrug combinations, increased rates of comorbidities and the ageing population. In this context, dose-dispensing aids such as multidrug punch cards are suggested to improve adherence to polypharmacy and clinical outcomes.14–16

Electronic monitoring is considered nearest to the gold standard in adherence measurement.17 Several studies used a pill bottle with a computer chip-equipped cap that records each opening of the bottle. Since of the design of this pill bottle, one lead drug can be monitored at one time.18–22 The recent development of printed electric circuitries and radio-frequency identification technology has made it possible to monitor polypharmacy by using a paper foil and a chip collecting real-time data (Confrérie Clinique SA, Lausanne, Switzerland) affixed on the back of a multidrug punch card.23 The POlypharmacy Electronic Monitoring System (POEMS) records date, time and location of medication removal of the whole therapy regimen.

We report on the first polypharmacy adherence monitoring over 12 months, integrated in a pharmaceutical care service for a patient with diabetes after hospital discharge. The patient was recruited within a pilot study to prove feasibility of a pharmaceutical care service with electronic adherence monitoring (ClinTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01759095).

Case presentation

A 65-year-old man was hospitalised at a large Swiss university hospital, from 28 January to 18 February 2013, for a sepsis by Staphylococcus aureus. His actual diagnoses included late-onset autoimmune diabetes in an adult (glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C): 8%, 30 January 2013) with manifest complications (diabetic foot with chronic osteomyelitis, non-proliferative retinopathy, polyneuropathy), coronary heart disease with double stenting during the actual hospitalisation (low-density lipoprotein (LDL): 2.83 mmol/L, 01 February 2013; triglycerides (TG): 1.82 mmol/L, 01 February 2013) and beginning heart failure (left ventricular ejection fraction 40%, blood pressure 183/93 mm Hg, 18 February 2013). Signs of beginning dementia were reported but not further investigated. The patient was retired, lived independently and alone in a middle-sized city and self-managed his medication by the use of a weekly pillbox. In January 2013, he was newly prescribed basal insulin by the general physician (GP) in addition to rapid-acting insulin that had been initiated years before. Amputation of digits I and II on the left foot had occurred after emergency hospitalisation in October 2010. He had no allergies and was a current smoker (30 pack years). At discharge, the patient was prescribed 10 different medications representing 15 pills in a four times per day regimen (table 1). Medication reconciliation, that is, the comparison of pharmacotherapy before and after hospitalisation, showed that three medications were newly introduced, one dosing frequency was reduced, one strength was augmented, and intake times changed from two to four times per day.

Table 1.

Medication plan handed out to the patient at hospital discharge

| Medication plan for (patient name)×(year of birth) |

Universitätsspital Basel Universitätsspital Basel |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician ___________ |

Date | dd.mm.yyyy |

||||||

| Ward ___________ |

Visum |  |

||||||

| Hotline: xxx xxx xx xx | ||||||||

| Medication |

Dosage |

|||||||

| Name | Dose | morning | noon | evening | night | Picture | Indication | Note |

| Irbesartan/htc | 300/12.5 mg | 1 |  |

Blood pressure | ||||

| Aspirine | 100 mg | 1 |  |

Blood thinning | Before meal | |||

| Atorvastatin | 40 mg | 1 |  |

Blood fat | ||||

| Pantoprazol | 40 mg | 1 |  |

Gastric acid | ||||

| Bisoprolol | 2.5 mg | 1 | 1 | np | Blood pressure | |||

| Clopidogrel | 75 mg | 1 |  |

Blood thinning | ||||

| Metformin | 1000 mg | 1 | 1 |  |

Sugar | |||

| Clindamycin | 300 mg | 2 | 2 | 2 |  |

Infection | Stop on 07-05-13 | |

| Insulin lisprum | np | Sugar | According to scheme | |||||

| Insulin glargine | np | Sugar | According to scheme | |||||

HTC, hydrochlorothiazide; np, no picture available.

Investigations

Adherence to polypharmacy was measured by a POEMS affixed on a disposable weekly multidrug frame card with 28 unit-of-use doses spread over 7×4 plastic cavities, filled with oral solid medication by the community pharmacist.

Treatment

During hospitalisation, a clinical pharmacist recommended referring the patient to a pharmaceutical care service consisting of individualised counselling (knowledge of medication), packaging of solid oral medication into multidrug punch cards (facilitation of polypharmacy management) and electronic adherence monitoring (measurement-guided medication management (MGMM)). Insulin management did not require further instruction. The responsible physician approved the recommendation and the patient provided written informed consent.

Two days prior to discharge, the pharmacist counselled the patient on indication, long-term benefit, adverse effects and correct use of all discharge medication using standardised information sheets. On the patient's request, the sheets were handed out instead of the official package inserts. The pharmacist instructed the patient on the use of the multidrug punch card and tested the patient's dexterity to remove the tablets.

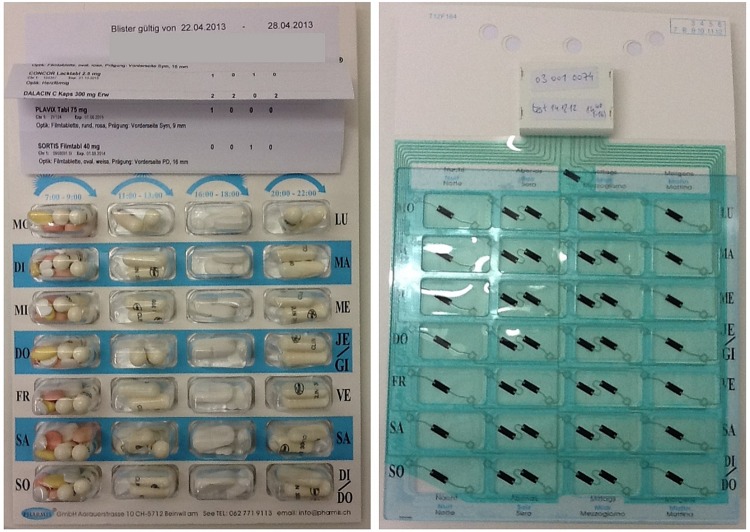

At discharge, the patient was provided with a POEMS-equipped multidrug punch card containing all his prescribed oral solid medication for 1 week along with his medication plan (table 1 and figure 1).

Figure 1.

Electronic multidrug punch card front (left) and back with affixed POlymedication Electronic Monitoring System (POEMS; right).

Five days after discharge, the patient was called to consolidate the safe and correct management of the electronic multidrug punch card. Exchange of empty multidrug punch cards for new filled ones occurred every 2–4 weeks at a predefined community pharmacy. The electronic records of the previous week were discussed following a protocol for MGMM17 and using elements of motivational interviewing24 such as open-ended questions, reflective listening, affirmative style, enhancement of personal motivation, setting goals and obtainment of a change of plan.

Outcome and follow-up

The monitoring period lasted from 18 February 2013 (discharge day) until 23 February 2014 and covered 371 days. In total, 54 multidrug punch cards with 899 unit-of-use doses were handed out. All returned multidrug punch cards were empty (taking adherence by pill count of 100%). In total 11 multidrug punch cards (20.4%) and 9 random days were not readable (technical failure), and 17 event times were not recorded, leading to lost data for 218 doses (24.2%). The patient removed eight pocket doses in anticipation of intakes away from home, which were excluded from the calculation. The summary of adherence statistics was derived from 673 electronic records.

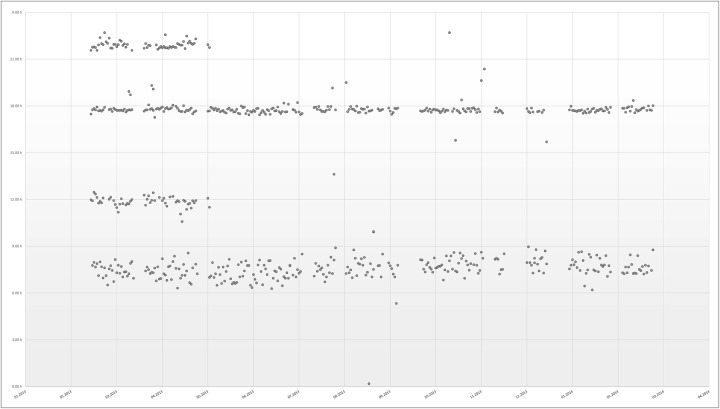

The first 79 days of treatment comprised four times per day intakes due to antibiotic treatment until 7 May 2013, and covered 21.3% of the observation period. On 8 May 2013, the GP augmented bisoprolol from 2.5 to 5 mg two times per day without influence on the number of pills or the intake times. The next 292 days comprised of two times per day intakes. A total of 278 doses were retrieved in the morning (four times per day: 63, two times per day: 215) in average at 7 h 34 min±55 min (four times per day: 7 h 24 min±27 min, two times per day: 7 h 36 min±1 h 1 min). The antibiotics assigned to be taken at noon (63 doses) and at night (65 doses) were taken on average at 12 h 22 min±2 h 6 min and at 21 h 44 min±44 min, respectively. A total of 267 doses were retrieved in the evening (four times per day: 57, two times per day: 210) on average at 17 h 39 min±1 h 1 min (four times per day: 17 h 45 min±8 min, two times per day: 17 h 37 min±1 h 14 min). The electronic records over the whole year are displayed in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Electronic records over the 1 year monitoring period.

A dosing interval was defined as correct if the time between doses was within 25% of the prescribed dosing interval, that is, ±3 h for a 12 h period two times per day and ±1.5 h for a 6 h period (four times per day). Overall, 96.9% of the dosing intervals were correct. All morning and evening doses of the four times per day regimen were taken in the grace period of 1.5 h, while 10/63 doses at noon and 4/65 doses at night were taken earlier or later, representing 5.4% of all four times per day doses. Of the two times per day regimen, 2/215 doses in the morning and 5/210 doses in the evening were taken outside the grace period of 3 h, representing 1.6% of all two times per day doses.

The patient kept all 17 planned appointments for multidrug punch card exchange and feedback sessions. He went on vacation thrice for several weeks. During the nine feedback sessions conducted regularly every 1–2 months, the patient confirmed the safe and correct use of the punch card. He was very satisfied with his electronic records and emphasised his efforts for a highly regular taking and timing adherence. He reported a strong integration of the process of medication taking into his daily routine, that is, coupled to mealtimes and insulin injection.

During the 12 months of monitoring, the patient had no readmission to hospital and no emergency visit. Laboratory values remained stable (LDL: 2.9 mmol/L, 29 January 2014; TG: 2.2 mmol/L, 29 January 2014; blood pressure: 193/88 mm Hg, 31 January 2014). HbA1C decreased to 7% (31 January 2014).

The patient reported high satisfaction with the intervention and a feeling of increased medication safety owing to the multidrug punch card use. The electronic records used during the feedback sessions helped the patient to gain confidence in medication management and to maintain perfect regularity of the intakes. The electronic monitoring did not bother him. At the beginning, the removal of the medication out of the multidrug punch card caused him trouble because the back layer was hard to push through. However, he got used to it quickly, reported no more problems and wished to continue using the punch cards after the end of monitoring.

Discussion

We found three similar case reports in the literature. First, a 79-year-old Japanese woman with type 2 diabetes and mild cognitive impairment took all medication three times per day from a sound-making and light-flashing electronic device.25 After 6 months, adherence by pill count was one missed dose per week (95%) and HbA1C decreased from 8.0% to 7.1%, demonstrating the efficacy of the electronic reminder device. Second, a 17-year-old girl treated for Fanconi Anaemia with eight drugs daily had an estimated adherence of 25%.26 She received 35 motivational interviewing sessions over 17 months. Adherence to the lead medication levothyroxine, measured by electronic pill bottle, showed a significant improvement of up to 82%, demonstrating the efficacy of motivational interviewing. Third, a 65-year-old Swiss man with epilepsy and suspected abuse of sleeping pills was monitored with electronic multidrug punch cards over 3 weeks.27 Inadequate medication intake behaviour could be corrected with feedback sessions.

Our patient, with pharmaceutical care service including electronic monitoring of adherence to polypharmacy and regular feedback on electronic records, successfully maintained perfect adherence and clinical stability over 1 year. An HbA1C level of 7% was reached during the 1-year monitoring period and represents the target level recommended by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes for elderly comorbid patients.28 The lowering of HbA1C by 1% is known to improve microvascular and macrovascular clinical end points significantly and to reduce all-cause mortality by 14%.29 In our case, the HbA1C reduction probably followed from the adjustment of insulin therapy 1 month before hospitalisation. However, the impact of multidrug punch cards was demonstrated by a mean HbA1C reduction of 0.95% in 36 patients with diabetes with oral antidiabetics after 8 months in a randomised controlled trial.30 We can thus suppose that, for our patient, the multidrug punch card acted as a railing and interrelated the oral therapy with the insulin therapy.

The challenging therapy plan of four times per day intake for over a fifth of the observation time and changes in daily routine due to vacationing had no influence on the patient's adherence. Since frequent dose dispensing and interruption in daily life were reported to negatively affect adherence,31–33 we assume that the multidrug punch card (as a practical tool) coupled with the continuous feedback sessions (as external motivator) were able to consolidate and maintain perfect adherence. This assumption is supported by a meta-analysis attributing a large effect to the intervention of feedback on electronic dosing history.34

We acknowledge some limitations. The substantial loss of data due to technical flaws in our first generation POEMS is inherent in newly developed technologies. The subsequent generation of electronic foils will be improved. Electronic monitoring is often criticised to assume rather than prove the patient's actual medication intake. However, we observed that patients usually accept monitoring and thus swallow the removed medication.35 Finally, the patient's being aware of observation is supposed to have an impact on the outcomes. However, a recent study showed that the use of an electronic device leads to a small, non-significant increase in adherence compared to standard packaging.36 In conclusion, this case is, to the best of our knowledge, the first report of long-term monitoring of polypharmacy associated with the benefit of successful disease management.

Learning points.

The pharmaceutical care intervention—comprising electronic monitoring of adherence to polypharmacy and recurrent feedback sessions—maintained optimal adherence and stabilised disease management.

The patient accepted the electronic monitoring of adherence to polypharmacy over 1 year and was satisfied with the service. He was even willing to continue with this service after study end.

Electronic monitoring of polypharmacy was feasible over 1 year and yielded valuable results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Balthasar Hug for his support in the clinical setting.

Footnotes

Contributors: FB and IA were involved in the patient’s care, conceptualised and designed the article, acquired, analysed and interpreted the data. FB drafted the article. IA and KEH revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the article to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Allemann S, Mil JWF, Botermann L et al. . Pharmaceutical care: the PCNE definition 2013. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36(3):544–55. 10.1007/s11096-014-9933-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care 2004;42:200–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation. Adherence to long-term therapies—evidence for action. World Health Organization, 2003. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosworth HB, Granger BB, Mendys P et al. . Medication adherence: a call for action. Am Heart J 2011;162:412–24. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97. 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM et al. . Medication nonadherence is associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2008;155:772–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA et al. . Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1836–41. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khdour MR, Kidney JC, Smyth BM et al. . Clinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPD. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:588–98. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03493.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes DA, Bagust A, Haycox A et al. . The impact of non-compliance on the cost-effectiveness of pharmaceuticals: a review of the literature. Health Econ 2001;10:601–15. 10.1002/hec.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez Payero M, Martinez Lopez de Castro N, Ucha Samartin M et al. . Medication non-adherence as a cause of hospital admissions. Farm Hosp 2014;38:328–33. 10.7399/fh.2014.38.4.7660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcum ZA, Gellad WF. Medication adherence to multidrug regimens. Clin Geriatr Med 2012;28:287–300. 10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kardas P, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol 2013;4:91 10.3389/fphar.2013.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regimen complexity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2011;9:11–23. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boeni F, Spinatsch E, Suter K et al. . Effect of drug reminder packaging on medication adherence: a systematic review revealing research gaps. Syst Rev 2014;3:29 10.1186/2046-4053-3-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJ et al. . Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:675–82. 10.2147/PPA.S29549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould ON, Todd L, Irvine-Meek J. Adherence devices in a community sample: how are pillboxes used? Can Pharm J 2009;142:28–35. 10.3821/1913-701X-142.1.28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes D. When drugs don't work: economic assessment of enhancing compliance with interventions supported by electronic monitoring devices. Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25:621–35. 10.2165/00019053-200725080-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell C, Conn V, Ashbaugh C et al. . Taking immunosuppressive medications effectively (TIMELink): a pilot randomized controlled trial in adult kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2011;25:864–70. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01358.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozuki Y, Schepp KG. Visual-feedback therapy for antipsychotic medication adherence. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;21:57–61. 10.1097/01.yic.0000177016.59484.ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krummenacher I, Cavassini M, Bugnon O et al. . An interdisciplinary HIV-adherence program combining motivational interviewing and electronic antiretroviral drug monitoring. AIDS Care 2011;23:550–61. 10.1080/09540121.2010.525613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Bruin M, Hospers HJ, van Breukelen GJ et al. . Electronic monitoring-based counseling to enhance adherence among HIV-infected patients: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol 2010;29:421–8. 10.1037/a0020335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen MI, Rigsby MO, Salahi JT et al. . Electronic monitoring and counseling to improve medication adherence. Behav Res Ther 2004;42:409–22. 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00149-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnet I, Hersberger KE. Polymedication Electronic Monitoring System (POEMS)—introducing a new technology as gold standard for compliance measurement. J Pat Comp 2012;2:48–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother 2009;37:129–40. 10.1017/S1352465809005128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamimura T, Ito H. Glycemic control in a 79-year-old female with mild cognitive impairment using a medication reminder device: a case report. Int Psychogeriatr 2014;26:1045–8. 10.1017/S1041610213002408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilliard ME, Ramey C, Rohan JM et al. . Electronic monitoring feedback to promote adherence in an adolescent with Fanconi anemia. Health Psychol 2011;30:503–9. 10.1037/a0024020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnet I, Walter PN, Hersberger KE. Polymedication Electronic Monitoring System (POEMS)—a new technology for measuring adherence. Front Pharmacol 2013;4:26 10.3389/fphar.2013.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB et al. . Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012;35:1364–79. 10.2337/dc12-0413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA et al. . Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405–12. 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simmons D, Upjohn M, Gamble GD. Can medication packaging improve glycemic control and blood pressure in type 2 diabetes? Results from a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2000;23:153–6. 10.2337/diacare.23.2.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vervloet M, Spreeuwenberg P, Bouvy ML et al. . Lazy Sunday afternoons: the negative impact of interruptions in patients’ daily routine on adherence to oral antidiabetic medication. A multilevel analysis of electronic monitoring data. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:1599–606. 10.1007/s00228-013-1511-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nair KV, Belletti DA, Doyle JJ et al. . Understanding barriers to medication adherence in the hypertensive population by evaluating responses to a telephone survey. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011;5:195–206. 10.2147/PPA.S18481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman CI, Limone B, Sobieraj DM et al. . Dosing frequency and medication adherence in chronic disease. J Manag Care Pharm 2012;18:527–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Kristanto P et al. . Identification and assessment of adherence-enhancing interventions in studies assessing medication adherence through electronically compiled drug dosing histories: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Drugs 2013;73:545–62. 10.1007/s40265-013-0041-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walter PN, Tsakiris DA, Romanens M et al. . Antiplatelet resistance in outpatients with monitored adherence. Platelets 2014;25:532–8. 10.3109/09537104.2013.845743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sutton S, Kinmonth AL, Hardeman W et al. . Does electronic monitoring influence adherence to medication? Randomized controlled trial of measurement reactivity. Ann Behav Med 2014;48:293–9. 10.1007/s12160-014-9595-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]