Abstract

A 34-year-old man was admitted to hospital via the accident and emergency department with severe right-sided abdominal pain and raised inflammatory markers. His pain settled with analgaesia and he was discharged with a course of oral co-amoxiclav. He was readmitted to the hospital 7 days later reporting cough and shortness of breath. His chest X-ray showed a raised right hemi-diaphragm, presumed consolidation and a right-sided effusion. As a result, he was treated for pneumonia. Despite antibiotic therapy his C reactive protein remained elevated, prompting an attempt at ultrasound-guided drainage of his effusion. Finding only a small amount of fluid, a CT of the chest was performed, and this showed a subphrenic abscess and free air under the diaphragm. A CT of the abdomen was then carried out, showing a perforated appendix. An emergency laparotomy was performed, the patient's appendix was removed and the abscess drained.

Background

A subphrenic abscess is an important differential diagnosis in a patient with a raised right hemi-diaphragm, abdominal pain and signs of infection. In addition, this case emphasises the importance of reviewing a patient’s recent hospital admission records as a way of informing clinical thought processes. This patient's initial presentation with abdominal pain was not identified as appendicitis. On readmission, the possibility of a subphrenic abscess was considered but not investigated fully, leading to a period where he was treated for right basal pneumonia with an associated pleural effusion.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to accident and emergency department with severe right-sided abdominal pain. On examination of his abdomen, he was found to have right-sided tenderness with maximal tenderness in his right upper abdominal quadrant. His blood tests showed raised white cell count (WCC) and C reactive protein (CRP). Further investigations included a chest X-ray, abdominal X-ray and abdominal ultrasound. These were unremarkable. His pain settled with analgesia and he was discharged home with a course of oral co-amoxiclav.

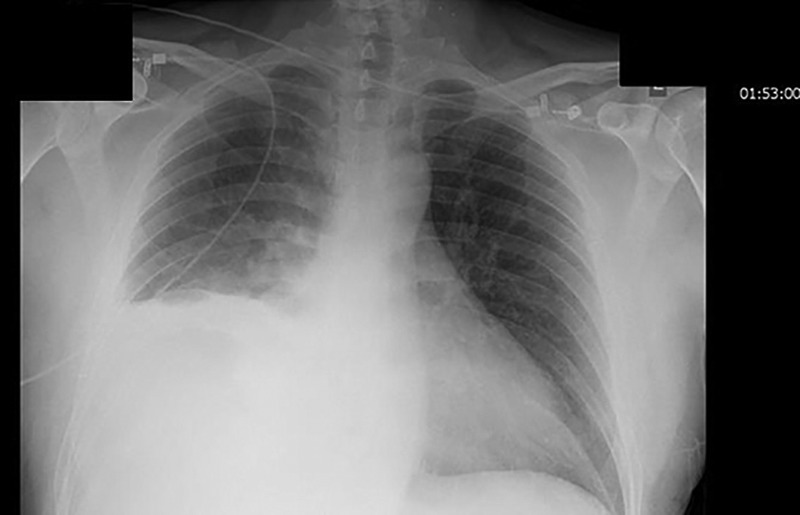

He was readmitted as an emergency 7 days later reporting cough and shortness of breath. He reported having felt unwell since his previous admission. He was found to have low peripheral oxygen saturations on room air. On examination, his breath sounds were reduced over his right lung base. His abdomen was generally tender with no guarding or organomegaly. His WCC, CRP and liver enzyme levels were elevated. His chest X-ray (figure 1) showed a raised right hemi-diaphragm with consolidation and an associated pleural effusion. He was admitted to the high-dependency unit and was started on intravenous antibiotics.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray performed on readmission.

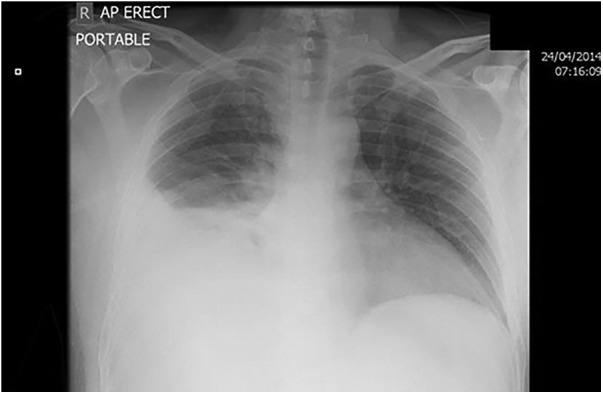

After 5 days, he was stepped down to a general medical ward as his oxygen saturations had improved. His antibiotics were changed as his WCC and CRP were persistently elevated. A repeat chest X-ray (figure 2) showed what appeared to be a worsening pleural effusion. On ultrasound-guided drainage of his effusion, very little fluid was visualised and drained. A CT of the chest was carried out, which showed free air under the diaphragm and a subdiaphragmatic collection (figure 3). A CT of the abdomen was then performed, which showed inflammatory changes suggestive of a perforated appendix. He was rushed to surgery for an exploratory laparotomy. His appendix was removed and 300 mL of fluid was drained from the abscess.

Figure 2.

Chest X-ray prompting attempted drainage of presumed empyema and subsequent CT.

Figure 3.

CT showing subphrenic abscess.

Investigations

Blood tests

Initial admission

WCC: 11.4×109/L

CRP: 5 mg/L

Platelet count: 219×109/L

Haemoglobin: 144 g/L

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP): 65 iu/L

Alanine transaminase (ALT): 42 iu/L

Re-admission

WCC: 12.0×109/L

CRP: 350 mg/L

Platelet count: 487×109/L

Haemoglobin: 119 g/L

ALP: 227 iu/L

ALT: 71 iu/L

Microbiology

Microscopy and culture of pleural fluid aspirate: no organisms seen, no growth observed.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses generated by the clerking doctor on initial admission were:

Cholecystitis

Appendicitis

Biliary colic

On readmission with symptoms of cough and shortness of breath the differential diagnoses generated by the clerking doctor were:

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

Raised liver function tests due to recent use of co-amoxiclav

Raised hemi-diaphragm due to subphrenic abscess

Treatment

Initial treatment on re-admission: Intravenous tazocin and clarithromycin, changed to meropenem after 5 days.

Definitive treatment: Surgical removal of appendix, drainage of subphrenic abscess and abdominal washout.

Outcome and follow-up

After surgery, the patient proceeded to make a full recovery and was discharged 1 week later. To date he has not had any further hospital admissions.

Discussion

A patient presenting with right-sided abdominal pain who is found to be maximally tender in his right upper abdominal quadrant should prompt a consideration of biliary pathology when generating a list of possible diagnoses. Appendicitis should also be considered if, as in this case, the patient is also tender in his right lower quadrant.

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common surgical emergencies.1 Roughly 40 000 patients in England are admitted to hospital with appendicitis every year. Perforation is a well recognised serious complication of appendicitis. The gold standard treatment for appendicitis is surgical removal of the appendix. However, studies have shown that there is a role for non-surgical management of appendicitis utilising antibiotic therapy.2 3

A review of over 200 000 patients in California with uncomplicated appendicitis managed with antibiotic therapy, showed 5.9% were unable to be adequately treated with antibiotics alone.4 The total risk of perforation was 3.2%. Within the 5.9% who had unsuccessful antibiotic therapy, the risk of perforation rose from 3.2% to 29.7%.4 Another study that randomly allocated 243 patients to surgical or medical management with co-amoxiclav found a significantly higher rate of peritonitis within the medically managed group.5

Our case shares certain parallels with the findings of these two studies. When the patient first presented with what in hindsight was appendicitis, he was discharged with analgesia and a course of oral co-amoxiclav. This can be roughly compared with the antibiotic regimes in the aforementioned studies. Therefore, antibiotic treatment failure would be a factor explaining his subsequent perforation.

A perforation can lead to widespread inflammation and infection through dissemination of faecal matter throughout the abdomen. It can also lead to localised inflammation and abscess formation due to the action of the omentum and surrounding viscera, which normally wall off the contaminating bacteria.6

In this case, the patient's initial perforation progressed to a subphrenic abscess. Other known causes of subphrenic abscesses include perforated gastric or duodenal ulcers and surgery.7

Subphrenic abscesses can be drained surgically or via the percutaneous route under ultrasound or CT guidance.8–10 There have also been a few cases drained using endoscopic ultrasound.11

Learning points.

A patient's previous admissions can provide vital information about their current admission.

A raised right hemi-diaphragm in association with sepsis and abdominal symptoms should lead to consideration of a subphrenic abscess.

The definitive treatment for a subphrenic abscess is drainage.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lewis S, Mahoney P, Simpson J. Easily missed? Appendicitis. BMJ 2011;343:d5976 10.1136/bmj.d5976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varadhan K, Humes D, Neal K et al. Antibiotic therapy versus appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. World J Surg 2010;34:199–209. 10.1007/s00268-009-0343-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skoubo-Kristensen E, Hvid I. The appendiceal mass: results of conservative management. Ann Surg 1982;196:584–7. 10.1097/00000658-198211000-00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCutcheon BA, Chang DC, Marcus LP et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with nonsurgically managed uncomplicated appendicitis. J Am Coll Surg 2014;218:905–13. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vons C, Barry C, Maitre S et al. Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid versus appendicectomy for treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:1573–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60410-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temple CL, Huchcroft SA, Temple WJ. The natural history of appendicitis in adults. A prospective study. Ann Surg 1995;221:278–81. 10.1097/00000658-199503000-00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dondelinger RF, Rossi P, Kurdziel JC et al. Interventional radiology. 1st edn New York: Thieme, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagi P, Dueholm S. Nonoperative management of the ultrasonically evaluated appendiceal mass. Surgery 1987;101:602–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeffrey RB Jr, Federle MP, Tolentino CS. Periappendiceal inflammatory masses: CT-directed management and clinical outcome in 70 patients. Radiology 1988;167:13–16. 10.1148/radiology.167.1.3347712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gee D, Babineau TJ. The optimal management of adult patients presenting with appendiceal abscess: “conservative” vs immediate operative management. Curr Surg 2004;61:524–8. 10.1016/j.cursur.2004.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustemović N, Opacić M, Bates T et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of an intra-abdominal abscess: a new therapeutic window to the left subphrenic space. Endoscopy 2006;38:E17–18. 10.1055/s-2006-944635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]