Abstract

A 47-year-old man presented with fever, a maculopapular rash of the palms and soles, muscular weakness, weight loss, faecal incontinence, urinary retention and mental confusion with 1 month of evolution. Neurological examination revealed paraparesis and tactile hypoesthesia with distal predominance, and no sensory level. Laboratory investigations revealed a venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) titre of 1/4 and Treponema pallidum haemagluttin antigen (TPHA) of 1/640, positive anti-nuclear antibodies of 1/640 and nephrotic proteinuria (3.6 g/24 h). Lumbar puncture excluded neurosyphilis, due to the absence of TPHA and VDRL. The diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) was established and even though transverse myelitis as a rare presentation of SLE has a poor outcome, the patient improved with cyclophosphamide, high-dose corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis was also established and the patient was treated with intramuscular benzathine penicillin G.

Background

The broad spectrum of clinical manifestations seen in certain infectious diseases often mimics the widespread features of chronic inflammatory disorders. The absence of specific clinical and laboratory aspects associated with autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), may toughen the diagnostic process due to the variability of possible differential diagnoses.1 We describe a patient who presented with signs and symptoms compatible with both SLE and secondary syphilis.

SLE is a systemic, multifaceted autoimmune inflammatory disease with an unknown aetiology. The pathology of this condition can be partly explained by the deposition of immune complexes in several organs, which triggers complement and other mediators of inflammation.2

SLE symptoms vary greatly. Constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, are probably multifactorial and have been related not only to disease activity but also to complications such as anaemia or hypothyroidism.3 Involvement of the musculoskeletal system is extremely common in patients with SLE,4 with myalgia, arthralgia and arthritis being the main manifestations.

Skin involvement occurs in 70–80% of patients, including the classic malar and discoid rashes, scarring alopecia, mouth ulcers and photosensitivity. Other cutaneous manifestations of SLE are Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, vasculitic purpura, telangiectasias and urticarial.3 Haematological features include normocytic normochromic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia.5

Renal disease affects about 30% of the patients with SLE and it remains one of the most important and life-threatening complications.

Pleuritis, causing chest pain, cough and breathlessness, may occur and pulmonary embolism must always be considered, particularly in those who have positive antiphospholipid antibodies. Cardiac disease involves asymptomatic valvular lesions, pericarditis and pericardial effusions, while myocardial disease is relatively rare.2

Neurological involvement of SLE is reported in 25–75% of patients and can involve any portion of the nervous system.6 It can manifest as a variety of neurological presentations, ranging from a mild headache to status epilepticus, aseptic meningitis, myelopathy or stroke. Acute transverse myelitis (TM) is usually a late complication of lupus, but in rare circumstances it may be the presenting manifestation of the disease.7 There is an association between this early presentation and antiphospholipid antibodies.8 9 The most common presenting symptoms are paraesthesias, numbness and weakness of the lower limbs, urinary retention, faecal incontinence, low back pain and fever.7 10–12

Syphilis is a disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, acquired through unprotected sexual intercourse and vertical transmission. Secondary syphilis is characterised by low-grade fever, lymphadenopathy, malaise, anorexia, weight loss and a mucocutaneous rash.13 Other less common presenting symptoms are hepatitis, nephrotic syndrome, glomerulonephritis, tenosynovitis and polyarthritis.14

Neurological manifestations of secondary syphilis include acute meningitis, sensorineural hearing loss, optic neuritis and Bell's palsy.14 Acute meningitis occurs in only 1–2% of patients. When it occurs, it does so in four different forms: aseptic meningitis (headache, nausea, fever, meningeal signs), acute syphilitic meningitis (with meningismus and focal neurological signs), acute syphilitic basilar meningitis (with meningeal signs and asymmetric cranial nerve palsies) and acute syphilitic hydrocephalus with papilloedema.15 16 Unlike tertiary syphilis, the meningeal involvement of secondary syphilis usually responds completely to penicillin.14 Untreated acquired syphilis progresses through several stages. Early or infectious syphilis consists of a primary stage, characterised by the chancre and regional lymphadenopathy, and a secondary stage (6 weeks after spontaneous healing of the chancre) characterised by mucocutaneous and multisystemic involvement. Skin lesions are usually symmetric, non-pruritic and non-bullous and may progress through four stages: macular salmon pink lesions are followed by maculopapular ones that resemble psoriasis but involve the palms and soles. Finally, papular indurated lesions may develop into necrotic, pustular ulcerations. Spontaneous healing of these lesions occurs and a latent asymptomatic period ensues.

Latent syphilis is a stage at which the features of secondary syphilis have resolved, though patients remain seroreactive. Some patients experience recurrence of the infectious skin lesions of secondary syphilis during this period.17

Case presentation

A 47-year-old man was referred to our department with extreme fatigability, muscular weakness affecting the four limbs, non-quantified weight loss, faecal incontinence, urinary retention, fever (38°C) and mental confusion with 1 month of evolution. On admission, the physical examination disclosed fever (38.3°C), discoloured mucosae, a maculopapular rash involving the palms and soles (figures 1 and 2), bilateral oedema of the inferior limbs extending until the knees and a hypotonic rectal sphincter on digital rectal examination. On pulmonary auscultation, there was a diminished vesicular murmur in both lung bases, without adventitious sounds.

Figure 1.

Maculopapular hyperpigmented rash present on the palm of the patient's hand.

Figure 2.

Maculopapular hyperpigmented rash present on the sole of the patient's foot.

On neurological examination, the patient was alert but inattentive, disoriented in time and space; his speech was clear and fluent. Cranial nerves were normal. Sensory examination revealed altered vibratory and positional proprioception, with tactile hypoesthesia on the lower limbs, without a sensory level, and unaltered pain sensation. There was a paraparesis with distal predominance: hip flexion 3/5 (Medical Research Council Scale), knee extension 3/5, knee flexion 3/5, plantar flexion 3/5, dorsal flexion 3/5 and finger extension 3/5. Deep tendon reflexes were present in the superior limbs, with a weak patellar reflex and absent ankle reflex. The patient was unable to walk due to lack of motor strength in the lower limbs.

Investigations

Blood tests revealed a pancytopenia with a normocytic normochromic anaemia of 8.1 g/dL of haemoglobin; leucocytes of 2900 mL/mm3; platelets of 116 000/mm; C reactive protein (CRP) of less than 0.29 mg/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 104 mm; serum creatinine (sCr) of 1.09 mg/dL; urea of 39 mg/dL with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 88 ml/min/L,73m2; venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) of 1/4 and T. pallidum haemagluttin antigen (TPHA) 1/640; negative HIV; hypoalbuminaemia of 2.12 g/dL; ferritin of 698 ng/mL; immunoglobulin G (IgG) of 3800 mg/dL, IgA of 234 mg/dL; IgM of 135 mg/dL; IgD of 1.1 mg/dL; and IgE of 460 mg/dL. Considering an autoimmune aetiology, the diagnostic process involved the search for autoantibodies in the serum. The results were positive fine granular anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) with a titre of 1/640, positive anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies, negative anti-Smith (anti-Sm) antibodies; negative anti double-stranded DNA antibodies (anti-dsDNA), positive anti-RNP (anti-ribonucleoprotein) antibodies and negative antiphospholipid antibodies.

For clarification of the mental confusion, head and medullary MRI were obtained (figures 3 and 4). The cervical cord was abnormally enlarged from C7 to T3 with T2-weighted images demonstrating increased signal intensity and T1-weighted images showing decreased signal intensity, without an obvious medullary compromise. There were multiple foci of hyper intensity in the posterolateral temporal topography at the left lateral ventricular horn, right posterior lenticular horn and head of the right caudate nucleus, without alterations on the perfusion in these areas. These findings were suggestive of non-specific sequel lesions, not being possible to totally exclude eventual foci of myelitis. Even though there were no significant alterations in the medullary MRI, the patient's clinical picture was highly suggestive of TM.

Figure 3.

Medullary MRI revealing multiple foci of hyper intensity in the posterolateral temporal topography at the left lateral ventricular horn, right posterior lenticular horn and head of the right caudate nucleus, without alterations on the perfusion in these areas. These findings were suggestive of non-specific sequel lesions, not being possible to totally exclude eventual foci of myelitis.

Figure 4.

Medullary MRI revealing multiple foci of hyper intensity in the posterolateral temporal topography at the left lateral ventricular horn, right posterior lenticular horn and head of the right caudate nucleus, without alterations on the perfusion in these areas. These findings were suggestive of non-specific sequel lesions, not being possible to totally exclude eventual foci of myelitis.

A lumbar puncture was then performed, which excluded neurosyphilis (due to negative VDRL and TPHA in the cerebrospinal fluid), and was compatible with an aseptic meningitis—a clear fluid with two cells without a defined predominance, proteins of 340 mg/dL, glucose levels of 28 mg/dL, pH of 8.5 and negative cultures; Tibbling index of 1.1 with IgG of 58 mg/dL, IgA of 2.23 mg/dL, IgM of 1.1 mg/dL and albumin of 146 g/dL, revealing dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier with intrathecal synthesis of IgG. It also revealed positive ANA, positive anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies and negative anti-dsDNA.

The patient also had proteinuria (200) and haematuria (Hb3+) with negative nitrites in spot urine. The 24 h urinalysis showed a nephrotic-range proteinuria (3.6 g). A renal biopsy was then carried out disclosing sclerosis involving 20% of the glomeruli, thickening and rigidity of the glomerular basement membrane, mesangial hypercellularity, lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate and dense mesangial and subepithelial immune deposits consistent with a class V lupus membranous nephritis (figures 5–7).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence revealing the presence of sparse granular deposits throughout the capillary membrane with a segmental distribution.

Figure 6.

Silver staining showing irregular basement membrane with speckles.

Figure 7.

Electron microscopy with reticuloendothelial and subepithelial deposits, some of them hump-shaped.

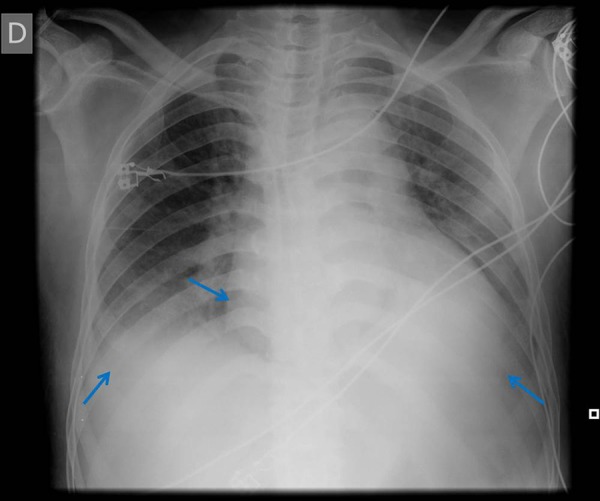

The anterior-posterior projection of the thoracic X-ray revealed blunting of the costophrenic angles with a cardiothoracic index of >50% (figure 8).

Figure 8.

Anterior-posterior projection of the thoracic X-ray revealing blunting of the costophrenic angles with a cardiothoracic index of >50%.

A thoracic and abdominal CT (figures 9 and 10) reported a small bilateral pleural effusion, a pericardial effusion with a 15 mm thickness and multiple coeliac, retroperitoneal and splenic lymphadenopathies.

Figure 9.

Thoracic CT showing a small bilateral pleural effusion, a pericardial effusion with a 15 mm thickness and multiple coeliac, retroperitoneal and splenic lymphadenopathies.

Figure 10.

Abdominal CT showing multiple coeliac, retroperitoneal and splenic lymphadenopathies.

A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed good global systolic function, without evident areas of dyskinesia, but with a hypertrophic interventricular septum; absence of auricular dilation; moderate aortic regurgitation; moderate pericardial effusion, mostly posteriorly (with a thickness of 1 cm), without thickening of the pericardium. The diagnosis of systemic lupus erythaematosus with haematological, renal, serosae and neurological involvement together with delayed latent syphilis of unknown duration was assumed.

Differential diagnosis

The non-specific clinical features of general fatigue, malaise and fever presented by our patient may have several causes. Infectious (such as viral or bacterial infections, infectious endocarditis, tuberculosis, syphilis or HIV), neoplastic (lymphoma, leukaemia, brain tumours) and autoimmune (SLE, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyositis).

Membranous glomerulonephritis can be primary, idiopathic or secondary to infections (hepatitis B and C, syphilis, malaria, schistosomiasis); neoplasia (breast, lung, stomach, kidney, oesophagus, neuroblastoma); medications (mercury, gold, anti-inflammatory agents, penicilamine, probenecid); autoimmune diseases (SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, primary biliary cirrhosis, myasthenia gravis, Sjögren syndrome, Hashimoto's thyroiditis) or other systemic diseases (Fanconi syndrome, sickle-cell anaemia, diabetes, Crohn's disease, sarcoidosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome).18

Viral and bacterial infections were excluded with negative serologies, and the hypothesis of a neoplasia was ruled out since the thoracic and abdominal CT were normal.

The neurological impairment, combined with urinary retention and faecal incontinence, may be caused by epidural or paraspinal abscesses complicating disc space infection, epidural or subdural haematomas, disc herniation and intra or extra medullary tumours,19 which were excluded by the brain and medullary MRI.

Regarding the main causes of TM, we have to, in the differential diagnosis, consider conditions such as multiple sclerosis, viral infections (herpes simplex virus, influenza, Epstein-Barr virus), immunisations (smallpox, influenza) and intoxications (penicillin, lead).8 Metabolic myelopathies should also be considered, the myelopathy acquired by copper deficiency and vitamin B12 deficiency being the most important.20

The presence of a mucocutaneous rash can be explained by vasculitides, pityriasis rosea, drug eruptions, psoriasis and acute febrile exanthemas. By being able to distinguish the typical rash (usually involving the palms and soles, and pinkish or dusky red) and determining the presence of positive serologic tests for syphilis (VDRL, TPHA), secondary syphilis can be assumed.13

Outcome and follow-up

Lupus nephritis is a common and potentially life-threatening manifestation of SLE, occurring in about 30% of SLE patients. The predictors of a worse prognosis are age greater than 30 years, black race, haematocrit less than 26%, serum creatine greater than 2.4 mg/dL, C3 complement less than 76 mg/dL,21 presence of anti-SSA antibodies, and failure to achieve remission with immunosuppressive drugs and corticosteroids. The progression to renal failure in patients with lupus nephritis is significantly greater in black patients, the segmental proliferative glomerulonephritis (class III, according to the WHO classification) being the predominant glomerular lesion in these patients.22 Regarding neurological involvement, and particularly in the case of TM, the prognosis is that extremely variable recovery may occur within the first 3–6 months although further improvement has been reported until up to 2 years; complete recovery is seen in only about 15% of patients.20

The treatment of SLE is threefold: managing acute periods of potentially life-threatening disease, minimising the risk of flares during periods of relative stability and controlling the incapacitating daily symptoms. Hydroxychloroquine and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used for milder disease, whereas corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapies are reserved for major organ involvement.2 Even though the prognosis for patients with lupus TM is usually not good, recent reports of better outcomes have emphasised early recognition and treatment with high-dose corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide and other immunosuppressive agents;23 this combination therapy is also thought to improve the prognosis of renal disease associated with SLE.24

In this case, a combination therapy was used, composed of pulses of cyclophosphamide, systemic corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine.

Considering our patient also presented with late latent syphilis of unknown duration, the treatment carried out was in accordance with the current therapeutic guidelines that recommend 7.2 million units of benzathine penicillin G, in three weekly doses of 2.4 million units, administered intramuscularly. The adequacy of therapy should be monitored after initial treatment by checking VDRL titre every 3 months until it becomes undetectable, bearing in mind that this process can take up to 2 years.

By the time of discharge, 4 months after admission, there was partial recovery of motor strength in the lower limbs (3/5 in the Medical Research Council scale), allowing the patient to walk with the support of crutches, and complete recovery of the control of urinary and rectal sphincters. The constitutional symptoms of fever and malaise resolved completely. Analytically, the patient had no evidence of anaemia (haemoglobin of 12.2 g/dL) or thrombocytopenia (platelets of 177 000/mm) and his inflammatory markers were a CRP of less than 0.29 mg/dL with an ESR of 56 mm. His renal function was normal with a sCr of 0.68 mg/dL and urea of 36 mg/dL (eGFR of 130 mL/min/1.73 m2), without proteinuria.

The patient is currently on a specialised motor rehabilitation unit where he undergoes daily physical therapy, with favourable results.

Discussion

This patient's constellation of signs and symptoms included generalised fatigue, rash, fever and malaise—all of which are fully compatible with both SLE and secondary syphilis. The hyper-pigmented rash involving the palms and soles, together with the blood analysis revealing a positive VDRL of 1/4 and TPHA 1/640, supported the diagnosis of secondary latent syphilis. However, considering that the analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid did not reveal the presence of VDRL or TPHA, the mental confusion and paraparesis could not be explained by neurosyphilis.

After proper investigation concerning the aetiology of this clinical setting, we assumed the presence of two concomitant diagnoses: SLE with haematological (pancytopenia), renal (membranous glomerulonephritis), serosae (pericardial and pleural effusions) and neurological (TM and aseptic meningitis) involvement, and late latent syphilis of unknown duration.

The immunological SLE background has been suggested to play a role in the susceptibility of patients to infections and the clinical manifestations can be atypical. Community-acquired pneumonia, urinary tract and soft tissue infections are common, and the responsible pathogens are usually the same as in the general population, including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but tend to behave more aggressively than in healthy individuals.25

Opportunistic infections are often underdiagnosed due to difficulties in their diagnosis, considering they can mimic or superimpose on active lupus. Listeriosis, nocardiosis, candidiasis, cryptococal meningitis, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and invasive aspergillosis are commonly described in patients with SLE. Severe Candida infection is the most commonly identified opportunistic fungal infection and is usually associated with steroid and cytotoxic therapy. Active lupus disease (SLEDAI>7) is probably the main risk factor for opportunistic infection.25

Considering the patient was immunocompromised, syphilis could be seen as opportunistic or as a superimposed infection. Other serologies typical of opportunistic organisms were all negative. The reason why it became so difficult to reach the definite diagnosis in this case was not only because the clinical picture could be the result of either SLE or syphilis, but also due to the fact that the investigations carried out could not exclude one or the other.

The renal biopsy also identified structural characteristics consistent with both of these diagnoses, not being able to confirm either of them as being the one responsible for the renal involvement of our patient. The numerous dense mesangial and subepithelial immune deposits and the tubuloreticular inclusions in the endothelium were consistent with SLE; however, the irregular distribution of the subepithelial, corymbiform-shaped deposits together with the presence of inflammatory cells (mononuclear and polymorphonuclear) were highly suggestive of an infectious origin, such as syphilis.

TM is a rare but serious complication of SLE,26 being reported in 1–2% of cases.8 Presentations such as faecal incontinence and urinary retention with paraparesis or tetraparesis are more typical of this type of myelitis than of milder forms of the disease commonly associated with SLE.27 28

There is evidence that the onset of TM in patients with SLE tends to follow a temporal pattern, with a mean time of occurrence of about 3 years after the initial diagnosis.29 Our patient's presentation does not coincide with this time frame, considering that TM was the first presentation of SLE.

Even though it was not possible to establish which of the diseases (SLE or syphilis) was responsible for some of the clinical features (distal oedema, mucocutaneous rash, weakness, fever), the treatment process chosen improved the clinical picture as a whole, with an extremely positive outcome for the patient.

Learning points.

The broad spectrum of clinical manifestations of certain infectious diseases such as syphilis, known as “the great imitator,” often mimics the features of chronic inflammatory disorders.

Renal involvement is characterised by proteinuria (>0.5 g/24 h) and/or red cell casts. A renal biopsy should be performed in such cases as its findings are useful to assess diagnosis and prognosis, and to guide the most suitable management.

Although acute transverse myelitis is a rare complication of systemic lupus erythematosus the presence of paraesthaesia, numbness and weakness of lower limbs, urinary retention, faecal incontinence, low back pain and fever should raise suspicion towards this condition.

Acknowledgments

Catarina Cabral and Ana Cadete were responsible for motor rehabilitation. Liliana Cunha performed the renal biopsy; Rita Manso and Samuel Aparício were the pathologists in charge of the case. Leonor Lopes provided imaging advice regarding the head and medullary MRI, while Willian Schmitt discussed the relevant findings in the abdominal CT.

Footnotes

Contributors: JAD, CS and CCH were on the medical staff when the patient was admitted. JAD and CS elaborated on the article, and CCH and JDA provided scientific expertise for the article design and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to refinement of the article and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Skillrud DM, Bunch TW. Secondary syphilis mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1983;26:1529–31. 10.1002/art.1780261218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manson JJ, Rahman A. Review: systemic lupus erythematosus. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2006;1:6 10.1186/1750-1172-1-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Menachem E. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a review for anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg 2010;111:665–76. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e8138e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zoma A. Musculoskeletal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2004;13:851–3. 10.1191/0961203303lu2021oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sultan SM, Begum S, Isenberg DA. Prevalence, patterns of disease and outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who develop severe haematological problems. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:230–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Cruz DP, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet 2007;369:587–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60279-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrianakos AA, Duffy JJ, Suzuki M et al. Transverse myelopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: report of three cases and review of literature. Ann Intern Med 1975;83:616–24. 10.7326/0003-4819-83-5-616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovacs B, Lafferty TL, Brent LH et al. Transverse myelopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: an analysis of 14 cases and review of literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2000;59:120–4. 10.1136/ard.59.2.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Cruz DP, Mellor-Pita S, Joven B et al. Transverse myelitis as the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus-like disease: good functional outcome and relevance of anti-phospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol 2004;31:280–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zerbini CAF, Fidelix TSA, Rabello GD. Recovery from transverse myelitis of systemic lupus erythematosus with steroid therapy. J Neurol 1986;233:188–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren RW, Kredich DW. Transverse myelitis and acute central nervous system manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27: 1058–60. 10.1002/art.1780270915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenic JG, Krohn K, Kelly RB et al. Transverse myelitis and optic neuritis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report with magnetic resonance imaging findings. Arthritis Rheum 1987;30:947–50. 10.1002/art.1780300818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dylewski J, Duong M. Teaching case report: the rash of secondary syphilis. CMAJ 2007;176:33–5. 10.1503/cmaj.060665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McPhee SJ. Secondary syphilis: uncommon manifestatons of a common disease. West J Med 1984;140:35–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swartz MN. Syphilis. In: Rubenstein E, Federman DD, eds. Scientific American medicine. Vol 2 New York: Scientific American Ilustrated Library, 1979:1–15. Chap 6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenholme GM, Harris AA, McKellar PP et al. Syphilitic meningitis with papilledema. South Med J 1977;70:1013–14. 10.1097/00007611-197708000-00037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medscape.com. Syphilis [updated 22 October 2014; cited 25 October 2014]. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/229461-overview.

- 18.Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D et al. Glomerular Diseases. In: Lewis JB, Neilson EG, eds. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 18th edn McGraw-Hill, 2011:2334–54. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boumpas DT, Patronas NJ, Dalakas MC et al. Acute transverse myelitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: magnetic resonance imaging and review of the literature. J Rheumatol 1990;17:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borchers AT, Gershwin ME. Transverse myelitis. Autoimmun Rev 2012;11:231–48. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin AH, Boumpas AT, Vaughan EM et al. Predicting renal outcomes in severe lupus nephritis: contributors of clinical and histologic data. Kidney Int 1994;45:544–50. 10.1038/ki.1994.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Evans J et al. Severe Lupus nephritis: racial differences in presentation and outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:244–54. 10.1681/ASN.2006090992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inslicht DV, Stein AB, Pomerantz F et al. Three women with lupus transverse myelitis: case reports and differential diagnosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:456–9. 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90150-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin HA, Klippel JH, Balow JE et al. Therapy of lupus nephritis. Controlled trial of prednisone and cytotoxic drugs. N Engl J Med 1986;314:614–16. 10.1056/NEJM198603063141004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sciascia S, Cuadrado MJ, Karim MY. Management of infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013;27:377–89. 10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period. A comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1000 patients. Medicine 2003;82:299–308. 10.1097/01.md.0000091181.93122.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colin W, Blair L, Ameen P. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis: a catastrophic presentation of a flare-up os systemic lupus erythematosus. CMAJ 2012;184:E197–200. 10.1503/cmaj.101213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Espinosa G, Mendizábal A, Mínguez S et al. Transverse myelitis affecting more than 4 spinal segments associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical, immunological, and radiological characteristics of 22 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010;39:246–56. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL. Nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus including the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. In: Handbook of clinical neurology. Vol 27 (71): systemic disease part III. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V, 1998:35–8. [Google Scholar]