Summary

This study assessed cellular and soluble markers of immune activation in HIV-1-seronegative men who have sex with men (MSM). MSM immune profiles were characterized by increased expression of CD57 on T cells and endotoxemia. Endotoxin presence was linked to recent high-risk exposure and associated with elevated cytokine levels and decreased CD4/CD8 T cell ratios. Taken together, these data show elevated levels of inflammation linked to periods of endotoxemia resulting in a significantly different immune phenotype in a subset of MSM at high risk of HIV-1 acquisition.

MSM represent approximately 2% of the US population, but account for approximately 63% of all new HIV-1 infections in the US [1]. Risk factors pertaining to MSM include anal intercourse [2], differences in transmission route and kinetics of viral dissemination [3], and inadequate access to preventative health care services [4-7]. Thus, MSM remain among the populations most highly affected by HIV-1 in both resource–rich and –poor settings [8].We recruited a cohort of MSM at high risk of HIV-1 acquisition to evaluate potential markers of immune activation and identify a potential high-risk immune profile in comparison to men at low risk of HIV-1 acquisition.

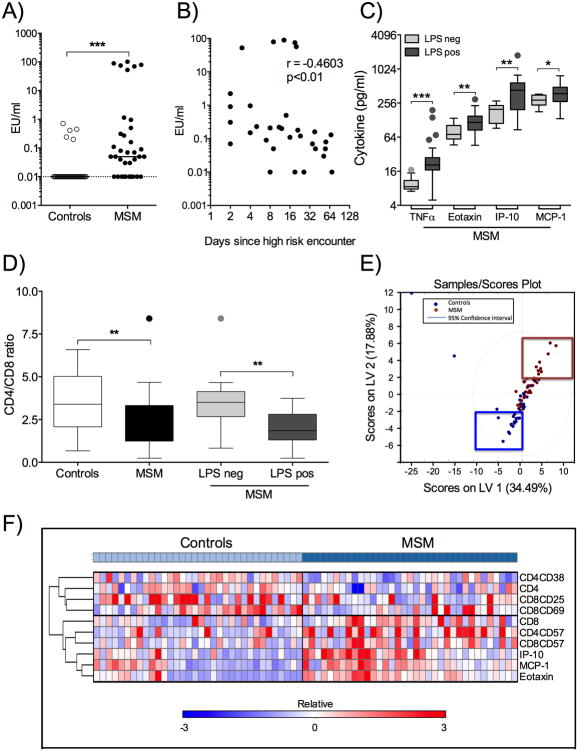

35 HIV-1 negative self-identified ‘high-risk’ MSM and 34 age- and ethnicity-matched self-identified ‘healthy, low-risk’ male control subjects were recruited at Fenway Health, Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital under IRB-approved protocols and included in this study. There was no statistically significant difference in age (unpaired two-tailed t-test: p=0.1) or distribution of ethnicities (Chi-square test for trend: p=0.3) between the two groups. Peripheral blood samples were collected and PBMC isolated by density gradient centrifugation [9]. Plasma was analyzed for presence of LPS by LAL assay (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and cytokine concentrations by 29-multiplex assay (HCYTMAG-60K-PX29, Millipore, Chicago, IL, USA). Plasma LPS was detected in 5/34 controls and 25/35 MSM (p<0.0001, Fisher's exact test) and levels of plasma endotoxin were significantly higher in MSM compared to controls (Figure 1A), but did not associate with history of STIs (p=0.9). Furthermore, levels of plasma LPS were inversely correlated with time since most recent sexual encounter without condom prior to date of blood draw (Figure 1B) and presence of LPS in plasma was associated with increased levels of plasma TNFα, Eotaxin, IP-10 and MCP-1 (Figure 1C). No other analytes differed significantly between LPS negative and positive MSM. Cells were stained with Fixable Live/Dead Stain, anti-CD4 (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA), anti-CD3 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CD8, anti-CD38, anti-HLA-DR, anti-CD57, anti-CD25, anti-Ki-67 and anti-CD69 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed by flow cytometry. MSM presented with a significantly lower CD4/CD8 ratio compared to controls (Figure 1D). When stratified according to LPS levels, MSM with no detectable plasma endotoxin had higher CD4/CD8 T cell ratios compared to MSM with detectable plasma endotoxin (Figure 1D). Spearman analyses showed a negative correlation between LPS levels and CD4/CD8 ratio (r=-0.5; p=0.002). Overall, these data imply an altered immune profile in MSM compared to controls as signified by a decreased baseline CD4/CD8 T lymphocyte ratio, which can be indicative of systemic immune activation [10] or immune pathology [11].

Figure 1. Analysis of Immune Profiles in MSM and controls.

A) Plasma samples from MSM (n=35, black circles) and controls (n=34, clear circles) were analyzed for endotoxin by LAL assay. Values are presented as endotoxin units (EU)/ml for each individual on a log10 scale (EU/ml range: 0-0.71 (controls); 0–101.6 (MSM)). Lowest values set for logarithmic graphing is shown by black dotted line (=0.01 EU/ml). B) Spearman correlation of LPS levels (EU/ml, log10) versus days since most recent high-risk exposure in MSM (n=32). C) Cytokine concentrations in MSM samples were stratified into endotoxin negative (n=10) and positive (n=25). Tukey box and whiskers plots of TNFα, Eotaxin, IP-10 and MCP-1 concentrations (pg/ml, log2) in endotoxin negative (detection limit, light grey boxes) and endotoxin positive (0.03-101.61 EU/ml, dark grey boxes) samples showing median, 5-95 percentiles and individual outliers. D) Tukey box and whiskers plots of CD4/CD8 ratios and group median for controls (n=34, white box), total MSM (n=35, black box) and MSM divided into LPS negative (n=10, light grey box) and LPS positive (n=25, dark grey box) with outliers shown. E) T cell marker and cytokine data were combined (n= 69) and analyzed by PLSDA comparing MSM with controls. PLSDA scores plot showing MSM (n=35, red dots) and controls (n=34, blue dots). F) Heat map clustering analysis of immune markers identified by PLSDA. Expression levels are displayed on a relative scale (-3 to +3) for each individual marker adjusted to group mean and standard deviation. Statistical significance is indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001.

To obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the differences in immune parameters between MSM compared to controls, we combined T cell markers and cytokine responses for analysis by partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLSDA) [12]. Ex vivo expression of %CD38, %HLA-DR, %CD25, %CD69, %CD57, %Ki67 and plasma cytokine concentrations were included in analysis. PLSDA showed separation according to latent variable (LV) scores (calibration error average of 0.18 and cross-validation error average of 0.22), suggesting differential association of various T lymphocytes marker and cytokine combinations with respect to MSM versus controls (Figure 1E). Specifically, higher plasma concentrations of Eotaxin, MCP-1, IP-10, and elevated bulk %CD8+, %CD57+CD4+ and %CD57+CD8+ T cells were observed in MSM, while elevated bulk %CD4+, %CD25+CD8+, %CD69+CD8+ and %CD38+CD4+ T cells were observed in controls. Heat map clustering using the GENE-E matrix visualization and analysis tool (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/GENE-E/) resulted in the same separation of immune markers for MSM versus controls (Figure 1F). Overall, these data demonstrate differential expression of several cytokines and markers of T cell activation and senescence in high-risk MSM compared to controls, as well as translocation of immune-activating bacterial products into the blood stream associated with decreased CD4/CD8 T cell ratio and elevated plasma cytokine concentrations.

In this cohort of MSM, the presence of elevated plasma endotoxin levels was associated with recent high-risk sexual encounter, decreased CD4/CD8 T cell ratio and increased plasma cytokine concentrations. We observed no difference in bulk %CD3+ T cell populations between MSM and controls, and others have shown that MSM and heterosexual men do not differ in their absolute CD4 counts [13]. The observed differences in CD4/CD8 T cell ratios, as well as elevated plasma cytokine levels and percentages of CD57+CD4+ and CD57+CD8+ T cell subsets in MSM might therefore be a reflection of immune activation following episodes of intermittent endotoxemia. The latter is supported by data from animal studies [14] and might contribute to alterations in immune homeostasis [15-17]. MSM furthermore presented with decreased percentages of CD38+CD4+ T cells, a phenotype linked to increased proliferative capacity but impaired cytokine production upon stimulation [18].

Several lines of evidence in HIV-1-exposed women suggest that enhanced levels of immune activation might lead to an increased risk of HIV-1 infection [19], and also be associated with faster disease progression should infection occur. Increased levels of TNFα can increase the risk of HIV-1 acquisition in women [20], and immune activation set point during early HIV-1 infection was shown to predict subsequent CD4+ T cell levels independently of viral load [21]. In conclusion, our study identified a subset of MSM with plasma endotoxemia and an immune profile suggestive of chronic immune activation and immune exhaustion. These immunological changes should be taken into account in future vaccination or prevention studies as increased inflammation can represent a risk factor for HIV-1 acquisition, as recently shown for seronegative exposed women [20].

Acknowledgments

We thank all blood donors, study participants, clinical staff and coordinators, Pamela Richtmyer, Suzane Bazner, Molly Amero and Mudia Uzzi. We thank the BWH PhenoGenetic Project and the Ragon Institute Flow Cytometry Core. Author contributions: CP designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote manuscript; JT performed subject recruitment and clinical data collection; MS and MRT performed sample processing and experiments; KA, DC and DL performed PLSDA; SJ co-wrote manuscript; TA and KM contributed to funding procurement; MA co-wrote manuscript, supervised study and contributed to funding procurement.

Funding sources: Institute, NIH [grant number P01 AI074415]

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.CDC. HIV Among Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9901-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1048–1063. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ribeiro Dos Santos P, Rancez M, Pretet JL, Michel-Salzat A, Messent V, Bogdanova A, et al. Rapid dissemination of SIV follows multisite entry after rectal inoculation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman D, Aggleton P, Williams M, Kong T, Reddy V, Harrad D, et al. Men who have sex with men: stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2012;380:439–445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60920-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyrer C, Sullivan PS, Sanchez J, Dowdy D, Altman D, Trapence G, et al. A call to action for comprehensive HIV services for men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380:424–438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61022-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer KH, Bekker LG, Stall R, Grulich AE, Colfax G, Lama JR. Comprehensive clinical care for men who have sex with men: an integrated approach. Lancet. 2012;380:378–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60835-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan PS, Carballo-Dieguez A, Coates T, Goodreau SM, McGowan I, Sanders EJ, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380:388–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer KH, Wheeler DP, Bekker LG, Grinsztejn B, Remien RH, Sandfort TG, et al. Overcoming biological, behavioral, and structural vulnerabilities: new directions in research to decrease HIV transmission in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 2):S161–167. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318298700e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naranbhai V, Bartman P, Ndlovu D, Ramkalawon P, Ndung'u T, Wilson D, et al. Impact of blood processing variations on natural killer cell frequency, activation, chemokine receptor expression and function. J Immunol Methods. 2011;366:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurence J. T-cell subsets in health, infectious disease, and idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:55–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sainz T, Serrano-Villar S, Diaz L, Gonzalez-Tome MI, Gurbindo MD, Jose MI, et al. The CD4/CD8 Ratio as a Marker T-cell Activation, Senescence and Activation/Exhaustion in Treated HIV-Infected Children and Young Adults. AIDS. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835faa72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau KS, Juchheim AM, Cavaliere KR, Philips SR, Lauffenburger DA, Haigis KM. In vivo systems analysis identifies spatial and temporal aspects of the modulation of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis and proliferation by MAPKs. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra16. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maini MK, Gilson RJ, Chavda N, Gill S, Fakoya A, Ross EJ, et al. Reference ranges and sources of variability of CD4 counts in HIV-seronegative women and men. Genitourin Med. 1996;72:27–31. doi: 10.1136/sti.72.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esplin BL, Shimazu T, Welner RS, Garrett KP, Nie L, Zhang Q, et al. Chronic exposure to a TLR ligand injures hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5367–5375. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appay V, Almeida JR, Sauce D, Autran B, Papagno L. Accelerated immune senescence and HIV-1 infection. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pillemer L, Schoenberg MD, Blum L, Wurz L. Properdin system and immunity. II. Interaction of the properdin system with polysaccharides. Science. 1955;122:545–549. doi: 10.1126/science.122.3169.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaddox LM, Goncalves PF, Vovk A, Allin N, Huang H, Hou W, et al. LPS-induced inflammatory response after therapy of aggressive periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2013;92:702–708. doi: 10.1177/0022034513495242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandoval-Montes C, Santos-Argumedo L. CD38 is expressed selectively during the activation of a subset of mature T cells with reduced proliferation but improved potential to produce cytokines. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:513–521. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0404262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taha TE, Hoover DR, Dallabetta GA, Kumwenda NI, Mtimavalye LA, Yang LP, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with increased acquisition of HIV. AIDS. 1998;12:1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naranbhai V, Abdool Karim SS, Altfeld M, Samsunder N, Durgiah R, Sibeko S, et al. Innate immune activation enhances hiv acquisition in women, diminishing the effectiveness of tenofovir microbicide gel. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:993–1001. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deeks SG, Kitchen CM, Liu L, Guo H, Gascon R, Narvaez AB, et al. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood. 2004;104:942–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]