Abstract

Background

In 2004 the World Health Organization WHO) released the Interim Policy on Collaborative TB/ HIV activities. According to the policy, for people living with HIV (PLWH), activities include intensified case finding, isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) and infection control. For TB patients, activities included HIV counselling and testing HCT), prevention messages, and cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT), care and support, and antiretroviral therapy ART) for those with HIV-associated TB. While important progress has been made in implementation, targets of the WHO Global Plan to Stop TB have not been reached.

Objective

To quantify TB/HIV integration at 3 primary healthcare clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Methods

Routinely collected TB and HIV data from the HCT register, TB ‘suspect’ register, TB treatment register, clinic files and HIV electronic database, collected over a 3-month period, were reviewed.

Results

Of 1 104 people receiving HCT: 306 (28%) were HIV-positive; a CD4 count was documented for 57%; and few received TB screening or IPT. In clinic encounters among PLWH, 921 (15%) had documented TB symptoms; only 10% were assessed by smear microscopy, and few asymptomatic PLWH were offered IPT. Infection control was poorly documented and implemented. HIV status was documented for 155 (75%) of the 208 TB patients; 90% were HIV-positive and 88% had a documented CD4 count. Provision of CPT and ART was poorly documented.

Conclusion

The coverage of most TB/HIV collaborative activities was below Global Plan targets. The lack of standardised recording tools and incomplete documentation impeded assessment at facility level and limited the accuracy of compiled data.

HIV-associated tuberculosis (TB) continues to pose a considerable global public health threat. In 2010, 1.1 million (13%) of the 8.8 million new TB cases globally were among people living with HIV (PLWH) and HIV accounted for 25% of the 1.4 million TB deaths. South Africa ranked third in the number of incident TB cases in 2010 with an estimated 61% of TB patients infected with HIV. Despite important efforts to curb the TB epidemic, South Africa (SA) was the only high-burden country where the TB burden continued to rise in 2010.1

To address the HIV-associated TB epidemic, in 2004 the World Health Organization (WHO) published the Interim Policy on Collaborative TB/HIV activities.2 To decrease the burden of TB in PLWH, the guidelines recommend intensified TB case-finding (ICF), isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) and infection control in healthcare and congregate settings. In 2008, these activities were packaged as the ‘3Is’. To decrease the burden of HIV in TB patients, the guidelines promote HIV counselling and testing (HCT) and HIV prevention methods for all TB patients, and cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT) and HIV/AIDS care and support including antiretroviral therapy (ART) for those co-infected.

In 2006, the Stop TB Partnership launched the ‘Global Plan to Stop TB 2011 – 2015’, providing a roadmap for scaling up prevention and treatment and research and development.3 The plan outlined specific TB/HIV collaboration targets, providing a framework for measuring WHO TB/HIV collaborative activities.

Despite an increasing body of evidence on the effectiveness and feasibility of collaborative TB/HIV activities and recent improvements in TB/HIV integration, implementation remains below targets.1,3 In 2010, key global indicators included merely 12% of eligible patients initiating IPT, and only 34% of TB patients were reported to know their HIV status.1

We reviewed routine TB and HIV data to quantify TB/HIV integration, measured against WHO and Global Plan targets,1,3 at 3 primary healthcare clinics in Johannesburg, SA.

Methods

Study setting and population

Three primary healthcare clinics in the Johannesburg metropolitan area were purposefully selected to represent different geographical catchment areas and non-governmental and Department of Health (DoH) clinics. All clinics provided TB diagnosis and treatment services, HCT, pre-ART care, and continuation of ART for stable patients. Two sites also served to initiate ART. TB and HIV services were performed vertically in different areas of the clinic by different staff who self-identified as either ‘TB’ or ‘HIV’ staff.

HIV counselling and testing was performed in those who requested this service, and provider-initiated HCT was offered to pregnant women and clients with AIDS symptoms, including TB and sexually transmitted diseases. CPT was indicated in PLWH with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3, as well as in symptomatic HIV disease and in all TB patients.4 PLWH were eligible for ART if their CD4 count was <200 cells/mm3 and/or they met the WHO criteria of stage 4 disease.5 PLWH were eligible for IPT if they were asymptomatic for TB and had a positive tuberculin skin test (TST), or they were a TB contact.4 Clinic clients with cough persisting for longer than 2 weeks were considered TB suspects, independent of HIV status. The first-line diagnostic for TB was smear microscopy. Smear-negative TB suspects were assessed further by culture (sputum analysis performed by the centralised National Health Laboratory Service) and chest X-ray (performed at nearest hospital).4

All clients who presented to 1 of the 3 selected clinics between 19 August and 19 October 2009 and who received TB and/or HIV services were included for analysis. Eligible clients were identified by review of relevant data sources, including the paper SA National DoH HCT register, TB case identification and follow-up register, TB treatment register, and an electronic HIV database (TherapyEdge) (Table 1). Records of all eligible individuals were reviewed 2 months after their clinic visit to allow sufficient time for activities to be performed and results to be captured. Infection control was assessed using a standardised risk assessment tool based on National TB Infection Control guidelines.6

Table 1.

Definition of study participants, data sources and activities reviewed

| Definition | Source | TB and HIV activities performed |

Reviewed (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT clients | Clinic clients with record of HIV test | HCT register Medical file |

Intensified TB screening Staging by CD4 count |

1 104 |

| PLWH encounters | Clinic visits by PLWH | Electronic HIV database TB case identification register |

Intensified TB screening Referral for TB investigation (if symptomatic) |

6 157 |

| TB suspects | Clinic client with record of diagnostic sputum investigation | TB case identification register HCT register Medical file |

Diagnostic assessment of TB suspect HCT CPT and ART (if eligible) |

602 |

| TB patients starting TB treatment |

Clinic client with TB start date during the study period | TB treatment register TB clinic file |

HCT CPT Staging by CD4 count ART if eligible |

208 |

HCT = HIV counselling and testing; PLWH = people living with HIV; CPT = cotrimoxazole preventive therapy; ART = antiretroviral therapy; TB = tuberculosis.

Individuals were categorised as: ‘HCT clients’ if they received HCT during the study period; ‘TB suspect’ if they had a diagnostic sputum investigation recorded; and ‘TB patient’ if they were started on TB treatment during the study period. As the WHO guidelines recommend symptom screening at every clinic visit, we included all PLWH encounters, including multiple encounters by individual PLWH that occurred during the specified time period.

Clinic records of clients who were newly tested HIV-positive were reviewed for documentation of TB symptom screening. Names were cross-checked with the ‘TB Detection and Follow up Sputum Register’ to assess if a sputum specimen was obtained. Data on PLWH were extracted from the TherapyEdge database. For every encounter registered, recorded symptoms and signs were reviewed. For every PLWH with recorded cough, night sweats, weight loss, axillary nodules or fever, the ‘TB Detection and Follow up Sputum Register’ was cross-checked to assess if a sputum specimen had been obtained. Files of clients entered into the TB Case Identification and Follow up Register and/or the TB register were reviewed for HIV testing, CD4 count, CPT status and ART status.

All data from standardised National DoH registers and TherapyEdge were entered for analysis in an electronic TB/HIV clinic and patient management program (eMuM®). Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the study population. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.2).

The Global Plan targets3 were used as the standards against which the implementation of these activities was measured. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina, the City of Johannesburg Health Department, and facility managers.

Results

Activities to reduce the burden of TB among PLWH

HCT clients were young (median age of 27 years) and the majority were female (75%). Of the 1 104 clients tested, 306 (28%) were HIV-positive. Only 57% of HIV-positive patients had a CD4 count result recorded, with a median count of 336 cells/mm3 (IQR 152 – 502). The proportion of clients newly diagnosed with HIV who were screened for TB symptoms could not be determined, as this activity was not systematically recorded. Based on review of the TB case identification register, only 2/306 (0.6%) HIV-positive HCT clients were assessed by smear microscopy at the time of their HCT visit.

There were 6 157 clinic encounters for 4 079 individual PLWH. The majority (79%) were for patients receiving ART (Table 2). The proportion of individuals with any recorded TB symptom of any duration was slightly higher for pre-ART than ART visits (17% v. 14%; p=0.04). In both populations, coughing was the most frequently recorded symptom (85% and 70%, respectively). Of the 921 clinic encounters with documented TB symptoms, only 91 (10%) resulted in sputum collection, with similar proportions of pre-ART and ART suspects being investigated (12% and 9%, respectively, p=0.20). Among the 91 TB suspects investigated, 8 smear-positive pulmonary TB cases and 9 smear-negative culture-positive TB cases were diagnosed. A culture result was missing or contaminated in 27% (22/83) of smear-negative TB suspects.

Table 2.

Intensified TB case finding during 6 157 clinic encounters among 4 079 individual PLWH at 3 primary care clinics in Johannesburg

| All n (%) |

Pre-ART n (%) |

ART n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N (%) | 6 157 (100) | 1 274 (21) | 4 883 (79) | |

| Any TB symptom recorded,* n (%) | 921 (15) | 214 (17) | 707 (14) | 0.04 |

| Cough | 678 (74) | 181 (85) | 497 (70) | |

| Weight loss | 138 (15) | 38 (18) | 100 (14) | |

| Night sweats | 169 (18) | 27 (13) | 142 (20) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 79 (9) | 14 (7) | 65 (9) | |

| Fever | 58 (6) | 14 (7) | 44 (6) | |

| Investigated for TB (if symptomatic), n (%) | 91 (10) | 26 (12) | 65 (9) | 0.20 |

| Smear-positive | 8 (9) | 2 (8) | 6 (9) | |

| Smear-negative, culture-negative | 52 (57) | 17 (65) | 35 (54) | |

| Smear-negative, culture-positive | 9 (10) | 1 (4) | 8 (12) | |

| Smear-negative, culture missing/contaminated | 22 (27) | 6 (23) | 16 (25) |

Patients may have reported more than one symptom.

The clinics did not collect information on IPT in an IPT register, pre-ART register or in the electronic HIV system, making an accurate estimate of the number of people receiving IPT difficult. According to the clinic directors, a small number of PLWH received IPT in 1 clinic; the other 2 clinics did not provide IPT.

An infection control plan existed in 2 sites, and posters on cough hygiene were displayed in all 3 facilities. Staff training was ad hoc; management reported that an effort was made to educate staff on TB and encourage them to know their HIV status and seek appropriate care. There was no triage system or fast-tracking of patients with coughing. Environmental controls were inconsistently used, 30% of windows remained closed. One site had ultraviolet germicidal irradiation in the TB clinic area. Personal protection for staff interacting with patients in the form of N95 respirator or surgical masks was available at one clinic, but use was not enforced. TB disease in healthcare workers was not documented.

Activities to reduce the burden of HIV among TB patients

Among the 602 TB suspects, 173 (29%) were known HIV-positive before their suspect visit but only half were documented as receiving HIV care (Table 3). Among the 429 TB suspects with unknown HIV status, 217 (51%) had a record of HCT offer. Of these, 110 (51%) were HIV-positive, 43 (20%) were HIV-negative, and 64 (29%) refused HIV testing. Overall, HIV status was recorded in 54% of TB suspects; 73% (95% CI 0.83 – 0.90) were HIV-infected.

Table 3.

HIV activities recorded among 602 TB suspects at 3 primary care clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa

| HIV counselling and testing, n (%) | |

| Known HIV-positive before TB suspect visit | 173 (29) |

| Referred from pre-ART care | 26 (15) |

| Referred from ART clinic | 65 (38) |

| No documentation of HIV care | 80 (46) |

| HCT at time of TB suspect visit (if unknown HIV status), n (%) | |

| Record of HIV counselling and/or testing | 217 (51) |

| HIV-positive | 110 (51) |

| HIV-negative | 43 (20) |

| HIV testing offered but refused | 64 (29) |

| No record of HIV counselling or testing | 212 (49) |

| TB suspects with documented HIV status at end of TB suspect visit | 326 (54) |

| HIV prevalence rate among TB suspects with recorded HIV status, % (95% CI) | 73 (0.83 – 0.90) |

| Staging by CD4 count | |

| Recorded CD4 count, n (%) | |

| Known HIV-positive before TB suspect visit | 132 (76) |

| Newly diagnosed HIV infection at time of TB suspect visit | 90 (82) |

| Median CD4 count, cells/mm3 (IQR) | |

| Known HIV-positive before TB suspect visit | 190 (90 – 351) |

| Newly diagnosed HIV infection at time of TB suspect visit | 183 (61 – 289) |

A CD4 cell count was documented in 78% (222/283) of HIV-positive TB suspects. The proportion of suspects staged by CD4 count and the median CD4 count did not differ significantly between those with known status at time of presentation and those tested on the day of the TB suspect visit (76% v. 82%, respectively; p=0.27; and 190 (IQR 90 – 351) v. 183 (IQR 61 – 289) cells/mm3, respectively).

Among the 602 TB suspects, 143 (24%) were diagnosed with active TB: 80 (56%) with smear-positive TB, 25 (17%) with smear-negative culture-positive TB, 27 (19%) based on clinical and/or radiological criteria and 11 (8%) with extrapulmonary TB. Among the 494 smear-negative TB suspects, a culture was requested in 345 (70%). The culture was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 5%, negative in 48%, and had missing results in 17%. TB treatment was initiated in only 81% (65/80) of TB suspects who were positive on smear microscopy and 26% (7/27) of smear-negative suspects with a positive culture.

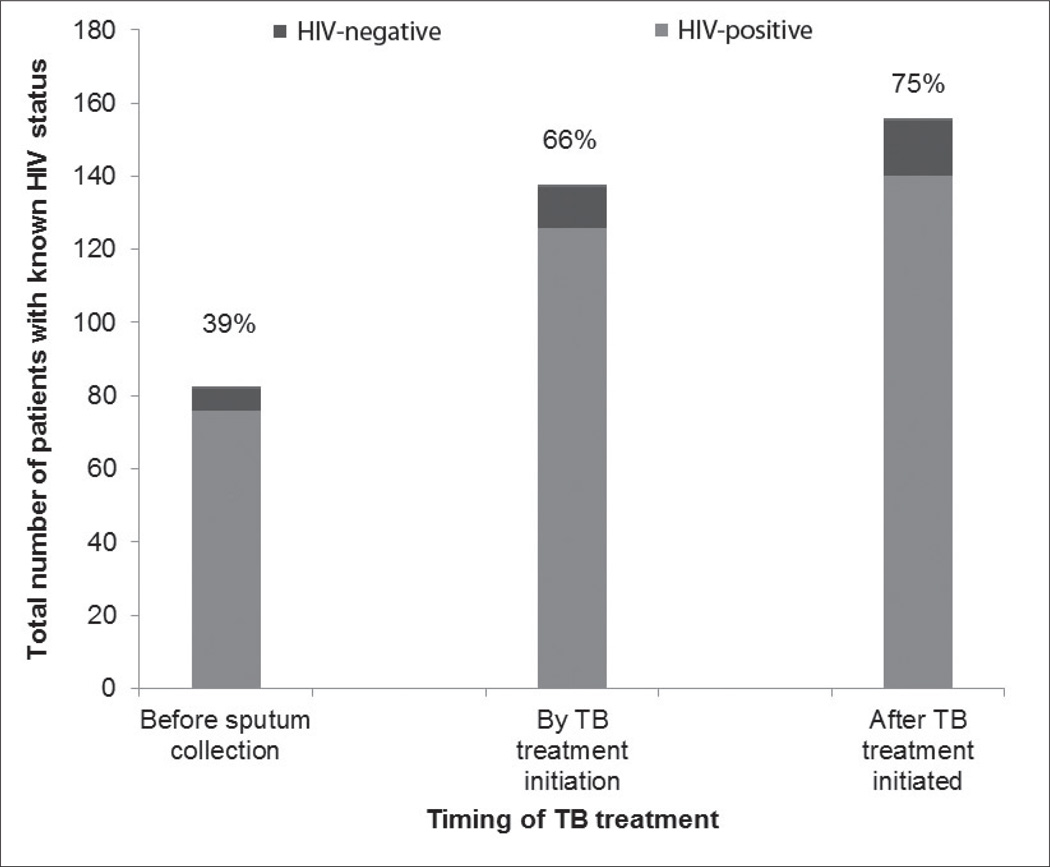

During the 3-month study period, 208 patients received TB treatment – the majority (81%) for pulmonary TB. The proportion of TB patients aware of their HIV status increased from 39% before TB diagnosis to 66% at time of TB treatment initiation, and to 75% during TB treatment (Fig. 1). Among the 155 TB patients with known HIV status, 90% were HIV-positive. A CD4 count was documented for almost all HIV-positive TB patients (88%). The median CD4 count was 131 cells/mm3 (interquartile range (IQR) 60 – 235), and the vast majority (107/123; 87%) had a CD4 count <350 cells/mm3. There was no documentation of HIV prevention and counselling for HIV-positive or -negative patients, but condoms were freely available at all 3 clinics. According to the staff, most HIV-positive TB patients received CPT, but the proportion receiving such therapy could not be quantified as it was not documented in the TB register, nor consistently recorded in patient files. ART status was not consistently recorded, and patients receiving TB treatment at a clinic not accredited for ART initiation might have initiated ART in another facility, making accurate reporting of the proportion receiving ART impossible.

Fig 1.

HIV counselling and testing among 208 TB patients registered at 3 primary care clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Discussion

In this quantitative evaluation of collaborative TB/HIV activities at 3 primary healthcare clinics, we confirmed the magnitude of the TB/HIV epidemic and observed strengths and gaps in the fight against TB/HIV at primary care level. However, our analysis was challenged by weaknesses in the routine data required to report on WHO core indicators developed to monitor TB/HIV activities.

The most important strength observed was the high rate of HIV and CD4 testing achieved among TB patients (75% and 88%, respectively). Important gaps included the lack of full TB/HIV integration despite availability of all services at one facility. Firstly, ART coverage among patients with TB could not be ascertained as ART was not documented in the TB register or on the TB treatment card. Secondly, integration of TB services into pre-ART care was poor. Patients newly diagnosed with HIV were not routinely screened for TB, even though a simple TB symptom screen could successfully have been integrated.7 People newly diagnosed with HIV were not offered IPT, even though most might have been eligible considering that the median CD4 count was 336 cells/mm3 (higher than the median CD4 count of 111 cells/mm3 recorded in large ART cohorts in sub-Saharan Africa).8 Thirdly, TB screening for people enrolled in HIV care was suboptimal. A formalised TB symptom screen was not performed and the TB screening outcome was not recorded as ‘no signs’, ‘suspect’, ‘on treatment’ or ‘not assessed’, as per WHO recommendations.9 Consequently, healthcare workers rarely acted upon the information. Only 10% of those presenting with symptoms of TB were assessed by microscopy, and IPT was initiated in only a few asymptomatic PLWH. The ‘Proportion of symptomatic PLWH assessed for TB’ may be a useful additional indicator. Finally, while some steps were taken towards TB infection control, this was not formally documented. The use of a standardised TB infection control risk assessment tool on a quarterly basis could facilitate monitoring. Given the lack of monitoring at facility level, it is not surprising that global data are lacking on the proportion of healthcare facilities providing services for PLWH that have TB infection control practices (indicator B.3.1) and the proportion of healthcare workers who develop TB (indicator B.3.2).9

We also observed shortcomings in non-integrated services. With regard to TB services, only 67% of patients with a microbiological diagnosis of TB initiated treatment, indicating important initial default of patients. Culture results were missing for 17% of specimens sent, resulting in poor service quality and a waste of resources. This could be improved by the introduction of more sensitive TB diagnostic tools with potential for use at point-of-care – such as the Xpert MTB/RIF10 test and the lipo-arabinomanna (LAM)11 assay. With regard to HIV services, a CD4 count was recorded for only 56% of people newly diagnosed with HIV, again suggesting a failure to engage and retain patients in care.

The scarcity of data hampered a comparison of our findings with those observed in other settings. Many have discussed the challenges of TB/HIV integration;7,12–14 however, most data are aggregated at country level and accurate reporting is complicated by the existence of 2 vertical programmes.15 Coverage of the different components at facility level is not well described. Only 2 other quantitative assessments at facility level have been published: in 2000 – 2002, Coetzee et al.16 observed many missed opportunities for TB and HIV prevention, diagnosis and management at primary care clinics in Khayelitsha; and in 2006, Scott et al.17 audited TB/HIV integration at 16 clinics in Cape Town, using a rapid (2 hours per clinic) audit tool and found poor capacity and weaknesses in quality and continuity of care.17

Despite our comprehensive review of data on a large number of clinic clients, our study suffered limitations. To assess routine care, data collection was retrospective; consequently, activities that were performed but not recorded could not be assessed. Furthermore, clients may have received care at other clinics, but we were unable to verify this due to the high number of clinics in the City of Johannesburg (n=90). Data were only reviewed on adult clinic clients; an assessment of TB/HIV activities in children would have been complementary. Finally, SA underwent significant policy changes regarding collaborative TB/HIV since the review was undertaken. ART eligibility criteria changed to a CD4 count <350 cells/mm3 for TB patients and pregnant women, and ART is currently indicated for all multi-drug resistant TB patients, regardless of CD4 count. The revised IPT guidelines removed the need for TST and included patients with previous TB and those on ART.

Conclusion

Despite the existence of effective interventions, clear policies and guidelines, the TB/HIV epidemic continues to rage. It is encouraging that most TB/HIV activities were implemented at the primary care clinics, but unfortunately, at coverage levels well below the Global Plan targets (Table 4).1 This highlights the vast number of opportunities to improve TB control and HIV care as we move towards meaningful TB/HIV integration. The poor quality of routine data was of concern, especially given that primary care clinics are expected to compile data from these sources to report to district and national levels for aggregation, analysis, dissemination and management of the TB and HIV programmes. Collection of TB/HIV collaborative data can be complicated by privacy concerns,18 the need to share data between 2 vertical programmes, and the lack of investment in monitoring and evaluation tools.15 Accurate monitoring of TB/HIV activities at all levels (facility, district, national and global) requires rationalisation and standardisation,18–19 with appropriate treatment cards, registers, cohort reporting forms, and supportive supervision.9,19 The implementation of integrated TB/HIV electronic data collection and clinic management tools has the potential to galvanise TB/HIV integration at primary care level. We need to ensure that every action is properly recorded and that every loop is closed from diagnosis to treatment of TB and HIV, to result in fully integrated patient care.

Table 4.

Coverage of TB/HIV activities compared with 2010 estimates for SA1 and The Global Plan to Stop TB targets3

| Indicator9 | Global Plan target (2011 – 2015) |

SA | Three primary care clinics in Johannesburg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of HIV-positive patients screened for TB in HIV care and treatment settings (indicator B.1.1) | 100% | 758 837 |

|

| Percentage of new HIV-positive patients starting IPT (indicator B.2.1) | 100% | 124 059 (12%) |

|

| Proportion of healthcare facilities providing services for PLWH that have infection-control practices including TB control (indicator B.3.1) | Target not set but 100% implied | NR | None satisfied the requirements of indicator B.3.1 |

| Proportion of healthcare workers employed in facilities providing care for PLWH who developed TB (indicator B.3.2) | Equal to background rate | NR | NR |

| Proportion of TB patients with known HIV status (indicator C.1.1) | 100% | 54% | 75% |

| Proportion of all registered TB patients with documented HIV status who are HIV-positive (indicator C.1.2.1) | NA | 60% | 90% |

| Availability of free condoms at TB services (indicator C.2.1) | 100% | NR | 100% |

| Proportion of HIV-positive TB patients who receive CPT (indicator C.3.1) | 100% | 74% | High according to healthcare worked, but poorly documented |

| Proportion of HIV-positive TB patients enrolled in HIV care services during TB treatment (indicator C.4.1) | 100% | NR | Poorly documented |

| Proportion of HIV-positive registered TB patients given ART during TB treatment (indicator C.5.1) | 100% | 54% | Poorly documented |

NA = not available; NR = not recorded.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Cassidy Henegar for help at the initial stages of the study, the City of Johannesburg senior management, regional directors and clinic management, and the Witkoppen Health and Welfare Centre senior management and staff.

Funding. The project was supported by funding from the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in a grant by USAID to Right to Care and the Institution (674-A-00-08-00007-00). Research training for L Page-Shipp was supported by DHHS/NIH/FIC 5 U2R TW00737-04.

Contributor Information

L Page-Shipp, Right to Care, Johannesburg.

Y Voss De Lima, Clinical HIV Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

K Clouse, Clinical HIV Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg; Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

J de Vos, GeoMed, Stellenbosch.

L Evarts, Public Health Leadership Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

J Bassett, Witkoppen Health and Welfare Centre, Johannesburg.

I Sanne, Right to Care, Johannesburg; Clinical HIV Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

A Van Rie, Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [accessed 10 November 2011]. Global Tuberculosis Control. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [accessed 1 October 2009]. Interim Policy on Collaborative TB/HIV activities. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [accessed 2 April 2011]. Global Plan to Stop TB 2011–2015. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. National Tuberculosis Management Guidelines. Pretoria: DoH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Pretoria: DoH; 2004. [accessed 3 November 2007]. National Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines 2004. http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/misc./2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. Pretoria: DoH; 2007. [accessed 8 May 2008]. National TB Infection Control Guidelines. http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/policy/2007/ipc-policy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard AA, El-Sadr WM. Integration of tuberculosis and HIV services in sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons learned. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:S238–S244. doi: 10.1086/651497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/651497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.May M, Boulle A, Phiri S, et al. Prognosis of patients with HIV-1 infection starting antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: A collaborative analysis of scale-up programmes. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60666-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [accessed 6 March 2010]. A guide to monitoring and evaluation for collaborative TB/HIV activities. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehme CC, Nicol MP, Nabeta P, et al. Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decentralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance : a multicentre implementation study. Lancet. 2011;6736(11):1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawn SD, Kerkhoff AD, Vogt M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a low-cost, urine antigen, point-of-care screening assay for HIV-associated pulmonary tuberculosis before antiretroviral therapy: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(3):201–209. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70251-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harries AD, Zachariah R, Lawn SD. Providing HIV care for co-infected tuberculosis patients : a perspective from sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(1):6–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong K, Thabethe Z, Hurtado R, et al. Challenges to the success of HIV and tuberculosis care and treatment in the public health sector in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:S491–S496. doi: 10.1086/521111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/521111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perumal R, Padayatchi N, Stiefvater E. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts: recognising missed opportunities for an optimal response to the rapidly maturing TB-HIV co-epidemic in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:243–250. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunneberg C, Reid A, Williams BG, et al. Global monitoring of collaborative TB-HIV activities. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coetzee D, Hilderbrand K, Goemaere E, et al. Integrating tuberculosis and HIV care in the primary care setting in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(6):A11–A15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01259.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1365-3156.2004.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott V, Chopra M, Azevedo V, et al. Scaling up integration: Development and results of a participatory assessment of HIV/TB services. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010;8:23–34. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2F1478-4505-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loveday M, Zweigenthal V. TB and HIV integration: obstacles and possible solutions to implementation in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(4):431–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02721.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1365-3156.2010.02721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harries AD, Zachariah R, Corbett EL, et al. The HIV-associated tuberculosis epidemic – when will we act? Lancet. 2010;29(375):1906–1919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60409-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0140-6736%2810%2960409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]