Abstract

Background and Purpose

Purpose in life, the sense that life has meaning and direction, is associated with reduced risks of adverse health outcomes. However, it remains unknown whether purpose in life protects against the risk of cerebral infarcts among community-dwelling older persons. We tested the hypothesis that greater purpose in life is associated with lower risk of cerebral infarcts.

Methods

Participants came from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Each participant completed a standard measure of purpose in life. Uniform neuropathologic examination identified macroscopic infarcts and microinfarcts, blinded to clinical information. Association of purpose in life with cerebral infarcts was examined in ordinal logistic regression models using a semiquantitative outcome.

Results

453 participants were included in the analyses. The mean score on the measure of purpose was 3.5 (Standard Deviation=0.47, range=2.1-5.0). Macroscopic infarcts were found in 154 (34.0 %) persons, and microinfarcts were found in 128 (28.3%) persons. Greater purpose in life was associated with a lower odds of having one or more macroscopic infarcts (Odds Ratio=0.535, 95% Confidence Interval=0.346-0.826, p=.005), but we did not find association with microinfarcts (Odds Ratio=0.780, 95% Confidence Interval=0.495-1.229, p=.283). These results persisted after adjusting for vascular risk factors of body mass index, history of smoking, diabetes, and blood pressure, as well as measures of negative affect, physical activity, and clinical stroke. The association with macroscopic infarcts was driven by lacunar infarcts, and was independent of cerebral atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis.

Conclusions

Purpose in life may affect risk for cerebral infarcts, specifically macroscopic lacunar infarcts.

Keywords: Aging, Purpose in Life, Cerebral Infarcts, Lacunes

Introduction

Purpose in life, a psychosocial construct, which involves having meaning and goal-directedness in life, is a key component of psychological well-being1. Older persons with a greater sense of purpose are less likely to develop adverse health outcomes, including mortality2,3, decline in physical function4, frailty5, disability6,7, Alzheimer's disease (AD)8 and clinical stroke9. The neurobiological basis underlying the beneficial effect of purpose in life is not well understood but may be related to other psychosocial factors that have been shown to influence cardiovascular disease risk10,11. However, the relationship of purpose in life with cerebral infarct pathology is unknown. Clinical strokes are largely underreported in old age. Neuroimaging captures more infarcts but may miss those that are under 3mm or microscopic.

In this study, using data from community-dwelling older persons enrolled in the Rush Memory and Aging Project, we tested the hypothesis that greater purpose is associated with lower risk of cerebral infarcts. All participants completed a standard assessment of purpose in life, were followed over multiple years and underwent autopsy after death. Our primary analysis examined associations of purpose with infarcts (macroscopic versus microscopic), and we evaluated significant associations by further controlling for a series of potential confounding factors. We also examined the associations with specific subtypes of infarcts.

Methods

Participants

The Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) is an ongoing clinical-pathologic cohort study of aging and dementia12. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center. Each participant signed an informed consent and an Anatomical Gift Act, agreeing to annual clinical evaluations and organ donation at the time of death. Since October 1997, the MAP study has enrolled more than 1,700 participants. By the time these analyses were performed, 719 participants had died, of which 554 (77.1%) had their autopsy results reviewed and approved by neuropathologists. We excluded participants who had incomplete purpose in life measure (N=50) or were demented at the purpose in life assessment (N=51). Primary analyses were performed on the remaining 453 participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study participants (N=453)

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age at analytic baseline (years) | 83.9 (6.0) |

| Age at death (years) | 89.6 (6.3) |

| Female sex | 310 (68.4%) |

| Education (years) | 14.5 (2.8) |

| Purpose in life | 3.5 (0.5) |

| Length of follow-up (years) | 5.7 (3.0) |

| Macroscopic infarcts | |

| No infarct | 299 (66.0%) |

| 1 infarct | 76 (16.8%) |

| Multiple infarcts | 78 (17.2%) |

| Microinfarcts | |

| No infarct | 325 (71.7%) |

| 1 infarct | 81 (17.9%) |

| Multiple infarcts | 47 (10.4%) |

| Cortical macroscopic infarcts | |

| No infarct | 394 (87.0%) |

| 1 infarct | 44 (9.7%) |

| Multiple infarcts | 15 (3.3%) |

| Subcortical macroscopic infarcts | |

| No infarct | 336 (74.2%) |

| 1 infarct | 64 (14.1%) |

| Multiple infarcts | 53 (11.7%) |

| Lacunar infarcts | |

| No infarct | 358 (79.0%) |

| 1 infarct | 60 (13.3%) |

| Multiple infarcts | 35 (7.7%) |

| Non-lacunar infarcts | |

| No infarct | 404 (89.2.0%) |

| 1 infarct | 41 (9.1%) |

| Multiple infarcts | 8 (.8%) |

SD: Standard deviation

Purpose in Life

Assessment of purpose in life was performed annually using a modified ten-item measure derived from Ryff's and Keyes's scales of Psychological Wellbeing1. During the assessment, participants rated their level of agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale. Ratings for negatively worded items were flipped, and scores at the item level were then averaged to obtain a composite score with a higher score indicating a greater sense of purpose in life, as reported previously13,14. A valid score requires at least 8 items answered by the participants, and 99.3% of the participants in the analysis answered all 10 items. In the primary analysis, the first valid score of purpose was used to examine the association with cerebral infarcts. Longitudinal data were also used to assess the potential change in purpose in life over time.

Cerebral Infarct and Other Pathologies

Brains were removed, weighed, and one hemisphere was cut coronally into 1 cm slabs and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde15. Macroscopic cerebral infarcts (i.e., infarcts visible to naked eyes) were identified using slabs and/or pictures from both hemispheres, and confirmed by histological review16. Blocks from at least 9 brain regions were cut into 6 micron sections which were stained with hematoxylin/eosin and examined for microinfarcts using microscopy17. We restricted our analysis to chronic infarcts. Lacunar infarcts were subcortical macroscopic infarcts that had all dimensions ≤ 10 mm, and non-lacunar infarcts had dimensions >10 mm. Each infarct measure was rated on a 3-level scale, including no infarct, 1 infarct, and multiple infarcts. Assessment of AD pathology and other cerebral vessel diseases are described in the Supplemental Methods.

Clinical Stroke and Other Covariates

Details on clinical stroke diagnosis and assessment of other covariates are provided in Supplemental Methods.

Statistical Analysis

To test the association of purpose in life with risk of cerebral infarcts, we first fit an ordinal logistic regression model with 3-level measure of total macroscopic infarcts as the categorical outcome, and the scores of purpose in life as the predictor, adjusted for age at death, sex and education. We repeated the model for microinfarcts. Both models estimate the odds ratios of the presence of infarct, as well as of multiple infarcts, for every 1 unit increase in the score of purpose in life. Next, we performed a series of analyses to assess the robustness of significant associations (Supplemental Methods). Finally, we explored whether the association differed by cortical versus subcortical infarcts using separate regression models. The score test18 assessed proportional odds assumptions which were adequately met in all models. Analyses were performed using SAS/STAT software, version 9.3 [SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC] and we used a nominal threshold of p<0.05 for statistical significance.

Results

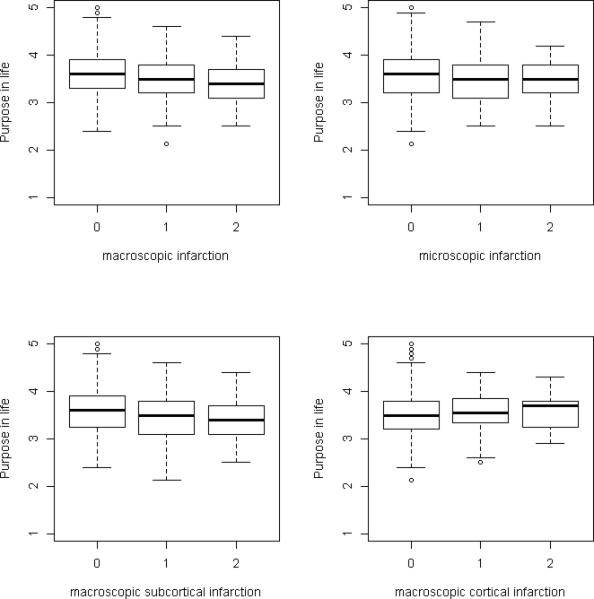

In 453 older persons, 114 (25.3%) had clinical stroke. Nearly twice as many participants had macroscopic or micro infarcts at autopsy (N=216, 47.7%). Specifically, 76 (16.8%) had 1 macroscopic infarct, and 78 (17.2%) having 2 or more macroscopic infarcts; 81 (17.9%) had 1 microinfarct and 47 (10.4%) having 2 or more microinfarcts. Participants with macroscopic infarcts were more likely to have microinfarcts (p<0.001). Older age at death was associated with greater odds of both macroscopic (p=0.035) and microscopic (p=0.032) infarcts. We found no association of sex or years of education with either type of infarct. The mean score on the measure of purpose in life was 3.5 (SD=0.5, range=2.1-5.0). Comparing a person with greater purpose (90th percentile) with one with less purpose (10th percentile), the score of our measure differed by approximate 1 unit. Figure 1 shows that the level of purpose in life differs by macroscopic infarcts but not by microinfarcts.

Figure 1.

Each Panel shows the boxplot of purpose in life by burdens of a specific type of cerebral infarcts (0=no infarct; 1=1 infarct; 2=multiple infarcts). Here each box is defined by the interquartile range, the bar inside the box is the median, and the wiskers are bounded by 1.5×interquartile range.

Purpose in life and Macroscopic Infarcts

In an ordinal logistic regression model adjusted for demographics, greater purpose in life was associated with lower odds of macroscopic infarcts (Table 2). Specifically, a one-unit increase of the score for purpose in life reduced the odds of having one or more macroscopic infarcts by almost 50% (odds ratio (OR) = 0.535, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.346-0.826, p=0.005). By contrast, we did not find an association of purpose with microinfarcts. We examined the potential sex difference in association of purpose with infarcts by adding a term for sex × purpose interaction; these were not significant suggesting no sex differences (Supplemental Table I). To account for the correlation between the two infarct outcomes, we reexamined simultaneously the associations of purpose in life with macroscopic and microinfarcts by fitting a bivariate Dale model. Results were unchanged (Supplemental Table II).

Table 2.

Purpose in life with macroscopic infarcts and microinfarcts

| Macroscopic infarcts ORs (95% CIs), p-values | Microinfarcts ORs (95% CIs), p-values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at death | 1.028 (0.995, 1.061), .098 | 1.034 (0.999, 1.070), .060 |

| Male sex | 1.253 (0.809, 1.942), .313 | 0.937 (0.588, 1.495), .785 |

| Education | 0.950 (0.882, 1.024), .179 | 1.004 (0.929, 1.084), .927 |

| Purpose in life | 0.535 (0.346, 0.826), .005 | 0.780 (0.495, 1.229), .283 |

The logits model the odds of more infarct pathology against less infarct pathology (that is, 1, 2 or more versus 0; and 2 or more versus 0 or 1).

Next, by leveraging longitudinal data for purpose in life, we assessed change in purpose over time (Supplemental Methods) and examined whether the association with infarcts was influenced by such change. On average, there was a relatively small decline in purpose in life relative to baseline differences (annual rate of decline= −0.044, p-value<0.001). The association with infarcts persisted after adjustment for the person-specific change in purpose in life (Supplemental Table III). These results support the relatively trait-like property of purpose in life. Separately, we explicitly examined the extent to which purpose in life measured many years versus just a few years prior to death differ by adding a model term for time from purpose assessment to death and its interaction with purpose. The interaction term was not significant, suggesting that the associations were not dependent on time between assessment and death (Supplemental Table IV).

We examined whether the relationship between purpose in life and macroscopic infarcts was affected by potential confounders (Supplemental Table V). First, because purpose in life reduces the adverse effect of AD pathology on change in cognition13, we investigated whether the association of purpose with macroscopic infarcts is influenced by AD pathology. Burden of AD pathology did not differ by infarcts status, and greater purpose in life was still associated with lower odds for more macroscopic infarcts after controlling for the burden of AD pathology.

Second, since purpose in life has been associated with vascular risk factors19, we repeated our model by including terms for body mass index (BMI), history of smoking, diabetes, and blood pressure. Higher systolic blood pressure was associated with greater odds for more macroscopic infarcts (p=0.015). However, the association of purpose in life and macroscopic infarcts persisted after controlling for these vascular risk factors.

Third, psychosocial risk factors are reported to be related to the risk of strokes or cerebral infarcts20-23. Thus, we controlled the terms for depressive symptoms, harm avoidance, childhood adverse experiences, and loneliness and the association was not changed.

Fourth, purpose in life is associated with physical activity24. Including the covariate for total daily activity, the association of purpose with macroscopic infarcts persisted. Finally, only a proportion of participants with macroscopic infarcts had a diagnosis of clinical stroke. We controlled for clinical stroke to examine whether the association of purpose in life with macroscopic infarcts is driven by those with clinical diagnosis. Notably, while clinical stroke was strongly associated with greater odds for macroscopic infarcts, the result on purpose in life was essentially unchanged.

Purpose in life and Lacunar Infarcts

To further explore whether the association with macroscopic infarcts differs by the anatomical location, we fit separate logistic regression models for cortical and subcortical macroscopic infarcts. A greater purpose in life was associated with fewer subcortical macroscopic infarcts but not with cortical macroscopic infarcts (Table 3). Because subcortical macroscopic infarcts can be further categorized into lacunar and non-lacunar infarcts, we also tested the associations with these subtypes of subcortical infarcts. The association was significant only with respect to the lacunar infarcts (Table 4), particularly gray matter lacunar infarcts (Supplemental Table VI).

Table 3.

Purpose in life with cortical and subcortical macroscopic infarcts

| Cortical macroscopic infarcts ORs (95% CIs), p-values | Subcortical macroscopic infarcts ORs (95% CIs), p-values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at death | 1.034 (0.987, 1.083), .164 | 1.026 (0.991, 1.063), .152 |

| Male sex | 1.354 (0.739, 2.481), .326 | 1.212 (0.749, 1.959), .433 |

| Education | 1.014 (0.915, 1.124), .784 | 0.949 (0.875, 1.030), .211 |

| Purpose in life | 1.126 (0.610, 2.076), .704 | 0.507 (0.315, 0.818), .005 |

The logits model the odds of more infarct pathology against less infarct pathology (that is, 1, 2 or more versus 0; and 2 or more versus 0 or 1).

Table 4.

Purpose in life with lacunar and nonlacunar infarcts

| Lacunar infarcts ORs (95% CIs), p-values | Nonlacunar infarcts ORs (95% CIs), p-values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at death | 1.017 (0.979, 1.056), .389 | 1.009 (0.960, 1.060), .728 |

| Male sex | 1.228 (0.733, 2.059), .436 | 1.073 (0.545, 2.110), .839 |

| Education | 0.942 (0.863, 1.030), .189 | 0.987 (0.880, 1.106), .821 |

| Purpose in life | 0.502 (0.300, 0.838), .009 | 0.669 (0.345, 1.300), .236 |

The logits model the odds of more infarct pathology against less infarct pathology (that is, 1, 2 or more versus 0; and 2 or more versus 0 or 1).

Finally, to assess whether the effect of purpose in life works through vessel diseases, we investigated the relationship with cerebral arteriolosclerosis and atherosclerosis. Purpose in life was not associated with the measure of arteriolosclerosis (p=0.619) or atherosclerosis (p=0.828). In a model adjusted for demographics and both measures of arteriolosclerosis and atherosclerosis, the association of purpose in life and lacunar infarcts robustly retained (Supplemental Table VII).

Discussion

We found that a greater sense of purpose in life is associated with about a 50% reduced likelihood of cerebral infarcts. The result was robust against the adjustment for a number of confounders. The association appears to be driven by lacunar infarcts, independent of cerebral large or small vessel disease.

A prior study shows that purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of clinical strokes in a group of participants aged 53-1059. We extend this finding in several ways. While the earlier study reports that less than 4% of the participants had clinical stroke over the four years of follow-up, our data show that at autopsy over 30% of our participants had macroscopic infarcts and over 25% had microinfarcts. This difference suggests that purpose in life is protective for ‘silent’ infarcts as well as clinical stroke. Thus, the association persists after controlling for clinical stroke. Second, the earlier study focused only on the outcome of clinical stroke in general, we were able to examine the associations with more specific subtypes of infarcts. Interestingly, we found that the most robust association is with lacunar infarcts.

Reasons for the differential association of purpose with infarct subtypes are not clear. One potential mechanism would be through small vessel disease (or arteriolosclerosis) which is more commonly related to lacunar infarcts. Indeed, we confirm that more severe arteriolosclerosis is associated with more lacunar infarcts. However, purpose in life is not related to either arteriolosclerosis or atherosclerosis. Further, the association persists after adjustment for burdens of arteriolosclerosis and atherosclerosis. This finding suggests that the association of purpose in life with cerebral infarct is likely independent of vessel disease.

More broadly, the neurobiological basis of the protective effect of purpose in life and other psychosocial constructs is complex and poorly understood. Our previous finding on purpose and AD pathology is consistent with the neural reserve theory, such that purpose is not directly related to AD pathology, instead older persons with greater purpose tend to function better cognitively while AD pathology accumulates in the brain. A recent study on neural correlates of purpose shows a positive association between purpose and insular cortex gray matter volume25. Different from the finding on AD, in this study, we show a direct relationship between greater purpose and lower risk for infarct pathology. Thus, purpose in life may work through other pathways to influence health outcomes in old age.

There are two other possible explanations for the association of purpose in life with infarcts. First, purpose may reduce the risk of infarcts by promoting healthy lifestyles. Prior work suggests that purpose is associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk19,26. However, the findings in our study persist after we adjusted for vascular risks of BMI, history of smoking, diabetes and blood pressure. While purpose in life is correlated with physical activity, controlling for daily activity in our data did not attenuate our finding. Stress or stress-related factors may also play a role in the association of purpose with infarcts. One study found that the combination of social inhibition and negative affect increased risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease27. However, our findings persist after the adjustment for measures of negative affect.

Second, purpose may directly be implicated in neuroendocrine function. Earlier studies show that psychological well-being is correlated with a number of biological markers such as salivary cortisol level, epinephrine, and norepinephrine28. Other potential mechanisms include inflammatory and potentially pro-coagulant and endothelial dysfunction markers such as High Sensitivity C-reactive protein, IL-6, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, IL-8, homocysteine, von Willebrand factor, E-selectin, P-selectin, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha11,29. Further work is needed to address these potential mechanistic pathways.

Purpose in life is correlated with many other psychological constructs including sense of coherence, resilience, and optimism30. Importantly, purpose in life constitutes a distinct dimension of psychological well-being and is a potentially modifiable factor that promotes healthy aging. One study reported that dispositional optimism protects against stroke31, and that purpose is associated with a lower risk even after controlling for optimism9. These measures have not been collected in our cohort and we cannot directly examine their relationships with purpose.

This study has the following strengths. Purpose in life was documented in community-dwelling persons without dementia. Participants were followed for over 5 years and underwent neuropathologic examination after death with high rates of autopsy. Our finding on association of purpose with reduced risk of infarct pathology is robust against confounding variables. Limitations are also noted. Although persons over 80 represent the fastest growing segment of the population, participants were older and had higher levels of education compared to the general population. Therefore, results may not generalize to other groups. Our finding that the association of purpose in life is primarily driven by lacunar infarcts requires replication from other studies.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to all the participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project. We also thank the staff at the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center for this work.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants: R01AG17917, R01AG24480, R01AG24871, R01AG33678, R01HL96944, R01AG34374, and The Illinois Department of Public Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All the authors report no relevant disclosures for this manuscript.

Dr. Yu receives grant support from National Institutes of Health.

Dr Boyle receives grant support from National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Wilson receives grant support from National Institutes of Health.

Dr Levine receives grant support from National Institutes of Health and PCORI.

Dr. Schneider has received consulting fees or sat on paid advisory boards for AVID radiopharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly Inc., and GE Healthcare. Dr. Schneider is a monitoring editor of the Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry and on the editorial board of International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. Dr. Schneider receives grant support from National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Bennett serves on the editorial board of Neurology; Dr. Bennett has received honoraria for non-industry sponsored lectures; Dr. Bennett has served as a consultant to Danone, Inc., Wilmar Schwabe GmbH & Co., Eli Lilly, Inc., Schlesinger Associates, Geson Lehrman Group. Dr. Bennett receives grant support from National Institutes of Health and research support from Zinfandel.

References

- 1.Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krause N. Meaning in Life and Mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64B:517–527. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:574–579. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins AL, Goldman N, Rodríguez G. Is positive well-being protective of mobility limitations among older adults?. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63:321–327. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.p321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gale CR, Cooper C, Deary IJ, Aihie Sayer A. Psychological well-being and incident frailty in men and women: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychological medicine. 2014;44:697–706. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;58:1925–1930. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6c259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaslavsky O, Rillamas-Sun E, Woods NF, Cochrane BB, Stefanick ML, Tindle H, et al. Association of the selected dimensions of eudaimonic well-being with healthy survival to 85 years of age in older women. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:2081–2091. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident Alzheimer's disease among community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:304–10. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced incidence of stroke in older adults: ‘The Health and Retirement Study’. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2013;74:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feller S, Teucher B, Kaaks R, Boeing H, Vigl M. Life satisfaction and risk of chronic diseases in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)-Germany study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emeny RT, Zierer A, Lacruz ME, Baumert J, Herder C, Gornitzka G, et al. Job strain-associated inflammatory burden and long-term risk of coronary events: findings from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg case-cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:317–25. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182860d63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Cur Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:648–665. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Yu L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. Archives of general psychiatry. 2012;69:499–504. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geda YE. A purpose-oriented life: is it potentially neuroprotective? Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1010–1. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2004;62:1148–55. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118211.78503.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Berry-Kravis E, Evans DA, Bennett DA. The apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele increases the odds of chronic cerebral infarction [corrected] detected at autopsy in older persons. Stroke. 2005;36:954–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000160747.27470.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke. 2011;42:722–727. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 13.2 User's Guide. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryff CD, Singer BH, Dienberg Love G. Positive health: connecting well-being with biology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1383–1394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Levine SR, Yu L, Anagnos SE, Buchman AS, et al. Emotional neglect in childhood and cerebral infarction in older age. Neurology. 2012;79:1534–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e25bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ostir GV, Markides KS, Peek MK, Goodwin JS. The association between emotional well-being and the incidence of stroke in older adults. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:210–5. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong JY, Zhang YH, Tong J. Qin, LQ. Depression and Risk of Stroke A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Stroke. 2012;43:32–37. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.630871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Levine SR, Yu L, Hoganson GM, Buchman AS, et al. Harm avoidance and cerebral infarction. Neuropsychology. 2014;28:305–11. doi: 10.1037/neu0000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooker SA, Masters KS. Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. [November 4, 2014];J Health Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1359105314542822. published online ahead of print August 7, 2014 http://hpq.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/07/28/1359105314542822.long. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Lewis GJ, Kanai R, Rees G, Bates TC. Neural correlates of the ‘good life’: eudaimonic well-being is associated with insular cortex volume. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2014;9:615–618. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Kubzansky LD, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older U.S. adults with coronary heart disease: a two-year follow-up. J Behav Med. 2013;36:124–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denollet J, Pedersen SS, Vrints CJ, Conraads VM. Predictive value of social inhibition and negative affectivity for cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: the type D personality construct. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:873–81. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryff CD, Dienberg Love G, Urry HL, Muller D, Rosenkranz MA, Friedman EM, et al. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:85–95. doi: 10.1159/000090892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiseman S, Marlborough F, Doubal F, Webb DJ, Wardlaw J. Blood markers of coagulation, fibrinolysis, endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in lacunar stroke versus non-lacunar stroke and non-stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;37:64–75. doi: 10.1159/000356789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nygren B, Aléx L, Jonsén E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:354–62. doi: 10.1080/1360500114415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim ES, Park N, Peterson C. Dispositional Optimism Protects Older Adults From Stroke The Health and Retirement Study. Stroke. 2011;42:2855–2859. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]