Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking among persons living with HIV (PLWH) is a pressing public health concern, and efforts to evaluate cessation treatments are needed. The purpose of the present study was to assess potential mechanisms of a cell phone-delivered intervention for HIV-positive smokers.

Methods

Data from 350 PLWH enrolled in a randomized smoking cessation treatment trial were utilized. Participants were randomized to either usual care (UC) or a cell phone intervention (CPI) group. The independent variable of interest was treatment group membership, while the dependent variable of interest was smoking abstinence at a 3-month follow-up. The hypothesized treatment mechanisms were depression, anxiety, social support, quit motivation and self-efficacy change scores.

Results

Abstinence rates in the UC and CPI groups were 4.7% (8 of 172) and 15.7% (28 of 178), respectively. The CPI group (vs. UC) experienced a larger decline in depression between baseline and the 3-month follow-up, and a decline in anxiety. Self-efficacy increased for the CPI group and declined for the UC group. Quit motivation and social support change scores did not differ by treatment group. Only self-efficacy met the predefined criteria for mediation. The effect of the cell phone intervention on smoking abstinence through change in self-efficacy was statistically significant (p<.001) and accounted for 17% of the total effect of the intervention on abstinence.

Conclusions

The findings further emphasize the important mechanistic function of self-efficacy in promoting smoking cessation for PLWH. Additional efforts are required to disentangle the relationships between emotional, distress motivation, and efficacious smoking cessation treatment.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, smoking cessation, cell phone intervention, mediation

1. INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking among persons living with HIV (PLWH) is a profound cause of morbidity and mortality (Lifson and Lando, 2012). Compared to the general population, PLWH are far more likely to be current smokers (Browning et al., 2013) and, subsequently, are confronted with numerous tobacco- and HIV-related health risks (Feldman and Anderson, 2013; Palella and Phair, 2011; Smith et al., 2010). In fact, PLWH who smoke cigarettes are at higher risk for acute bronchitis, bacterial pneumonia, pulmonary disease, non-AIDS and AIDS-defining cancers, and overall mortality (Burke et al., 2004; Crothers et al., 2005; Engels et al., 2006; Lifson et al., 2010). Smoking may also weaken the virological response to antiretroviral therapies (Feldman et al., 2006) by as much as 40% (Miguez-Burbano et al., 2003). In fact, recent evidence from a large cohort study indicates that > 60% of deaths among PLWH can be attributed to smoking (Helleberg et al., 2012). Therefore, smoking cessation interventions are critical for improving medical management and maximizing survival for PLWH.

To date, relatively few efforts to evaluate and/or implement smoking cessation interventions for PLWH appear in the literature (Moscou-Jackson et al., 2014). Moreover, published results from randomized clinical trials (RCT) generally indicate modest long- term smoking abstinence rates and small, or no treatment group differences (Gritz et al., 2013; Humfleet et al., 2013; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2009). While the precise explanation for the higher than expected smoking relapse rates and lack of treatment effects among HIV-positive populations are unknown, variables such as low socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, depression, anxiety, stress, alcohol abuse, and illicit drug use are likely contributing factors (AMA, 1996; Breslau and Johnson, 2000; Degenhardt and Hall, 2001; Diaz et al., 1994; Greenwood et al., 2005; Halkitis et al., 2000). Moreover, efforts to identify the actual mechanisms by which interventions facilitate smoking abstinence offer the potential to meaningfully inform the development of the next generation of interventions for PLWH.

In the current study, mediators of a cell phone-delivered intervention for HIV-positive smokers were evaluated. Several key considerations informed the development of this smoking cessation intervention. First, cell phones were chosen as the intervention delivery mode due to the many barriers (e.g., transportation, lack of landlines, housing instability) that reduce the feasibility of more traditional smoking cessation treatment options (e.g., in person individual or group counseling, quit line counseling, home computer delivered treatment) in the targeted low socioeconomic status HIV-positive population (Honjo et al., 2006; Lazev et al., 2004). Moreover, a growing literature suggests that cell phone-based smoking cessations interventions are feasible and effective for both PLWH and other populations (Vidrine et al., 2006; Whittaker et al., 2012). Content for the intervention was based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Motivational Interviewing (MI) principles, and designed to increase self-efficacy and social support, while maintaining quit motivation (Miller and Rollnick, 1991; O’Donahue et al., 2003). The intervention was also designed to address general feelings of emotional distress, which are often associated with smoking relapse (Vidrine et al., 2012). Therefore, an a priori hypothesis of this study was that the cell phone intervention’s effect on abstinence would be mediated by quit motivation, self-efficacy, social support, and emotional distress.

2. METHODS

2.1 Study Site and Participants

Data for this study are derived from a larger smoking cessation randomized controlled trial (RCT) for HIV-positive smokers (Gritz et al., 2013; Vidrine et al., 2012). All participants enrolled in the parent study (n=474) were recruited from the Thomas Street Health Center (TSHC) of the Harris Health system in Houston, Texas between February, 2007 and December, 2009. TSHC is a county-administered HIV clinic serving a predominantly low-income, medically indigent, and minority patient population. To be eligible for the RCT, individuals were required to be: HIV-positive, age >/=18 years, current smokers, willing to set a quit date within 7 days, and English or Spanish speaking. Participants were excluded if they were enrolled in another smoking cessation program and/or physician-deemed ineligible based on medical or psychiatric conditions. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

2.2 Procedures

After informed consent was obtained, participants completed an audio computer–assisted self-interview (ACASI) consisting of demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial measures. Study participants then received brief provider advice to quit, and were subsequently randomized using a computerized minimization procedure to one of two treatment conditions [usual care (UC) or cell phone intervention (CPI)]. In addition to brief provider advice, participants in UC received self-help materials and instructions on how to obtain nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) at TSHC. CPI participants received a prepaid-cell phone and an 11-call proactive counseling regimen in addition to all of the UC components (i.e., brief advice, written materials, and instructions on how to obtain NRT). The content of the CPI counseling sessions and the call schedule can be found in Table 1. Both the UC and CPI treatments were informed by recommendations from the Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline (Fiore et al., 2008). Further details about the procedures and the intervention have been previously published (Gritz et al., 2013; Vidrine et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Schedule and content of proactive counseling calls

| Call | Time of Call | Content of Call |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 day prior to quit date | Preparing to quit - why quit when you’re HIV- positive? Making the commitment to quit |

| 2 | Quit Day | Quitting smoking – getting through the first day |

| 3 | 2 days post quit date | Surviving withdrawal - withdrawal facts and coping skills |

| 4 | 4 days post quit date | Managing high risk situations |

| 5 | 7 days post quit date | Stress, negative affect & smoking |

| 6 | 10 days post quit date | Improving support and asserting yourself |

| 7 | 2 weeks post quit date | Reviewing problem solving & dealing with lapses |

| 8 | 4 weeks post quit date | Reinforcing benefits of being an HIV+ nonsmoker |

| 9 | 6 weeks post quit date | Maintaining commitment – keeping motivated |

| 10 | 9 weeks post quit date | Successes and challenges in smoking cessation |

| 11 | 12 weeks post quit date | Long-term relapse prevention |

Follow-up demographic, health behavior (i.e., smoking, alcohol, and illicit drug use), and psychosocial assessments were conducted at 3, 6, and 12 months post-enrollment. These assessments consisted of an ACASI (mirroring the baseline assessment) and biological confirmation of smoking status using expired carbon monoxide (CO). Participants were given a $20 gift card after completing each assessment. The current analysis focuses on the 350 participants (172 in UC and 178 in CPI) who completed the 3-month follow-up.

2.3 Measures

Treatment group membership, CPI vs. UC, was the independent variable of interest. The primary outcome variable was biochemically verified smoking abstinence at the 3-month follow-up. Smoking abstinence was operationally defined as self-reported abstinence within the past 7 days at the time of assessment and a CO level <7ppm. The hypothesized treatment mediators included depressive symptoms, anxiety, social support, quit motivation, and self-efficacy. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 20-item Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff, 1977); anxiety was assessed with the state component of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-State) (Spielberger et al., 1970); social support was assessed with the 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL; Cohen et al., 1985; Cohen and Wills, 1985); quit motivation was assessed with the Reasons for Quitting Questionnaire (RFQ), which provides scores for both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Curry et al., 1990); and smoking abstinence self-efficacy was assessed with a 9-item scale developed and validated by Velicer and colleagues (1990). Each of these self-report measures is widely used and has solid psychometric properties. Following the guidelines suggested by Allison (1990), change scores between the 3-month follow-up and baseline assessment were calculated.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Mediation analysis for binary outcomes was employed. (MacKinnon, 2008; MacKinnon et al., 2007). The predefined criteria for mediation were that both paths from predictor to mediator and from mediator to outcome should be significant in order to test for mediation effects. Thus, evidence of mediating effects is found when the intervention exerts a significant effect (a path) on a potential mediator (e.g., change in depression) which, in turn, exerts a significant effect (b path) on smoking abstinence. The indirect effect is the product of the a and b paths. In the estimation of direct effects (b) of the mediator on the outcome, the intervention effects (c path) were also estimated simultaneously with the indirect effect. Logit regression with rescaling was used for the analyses to estimate the mediation effects. The reason for rescaling in estimating mediation effects is that a binary mediator has a different scale when it is a predictor of an outcome and when it is the outcome (MacKinnon and Dwyer, 1993). Multiplication of each coefficient of the two equations by the standard deviation (SD) of the predictor variable and division by the SD of the outcome variable corrects for the differences in scales. Statistical significance of the point estimates for the indirect effects was assessed using bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals with 5,000 replicates. The proportion of the effect of treatment on the outcome mediated was estimated by dividing the mediation effect to the total effect. Analyses were conducted in R version 3.0.1 (www.r-project.org).

3. RESULTS

Descriptive statistics, including smoking history, HIV exposure, and the socio-demographic profile of the entire sample (n=474) have been previously described (Vidrine et al., 2012). The analytical sample for the current study included the 350 participants (172 in UC and 178 in CPI) who completed the 3-month follow-up. Seventy two percent of the UC group and 75% of the CPI group were retained at the 3-month follow up. At baseline, mean age was 45 (SD = 8.1) years, 30% were female, and mean years of education was 11 (SD = 2.6). The majority of the participants identified themselves as African American (76%) followed by White (12%), and Hispanic (9%). No significant socio-demographic differences between the UC and CPI were observed. Missingness was not related to any of the variables collected at baseline and at the 3-month time-point.

Table 2 presents the means and SDs at baseline and 3 months and the change score of each potential mediator and the frequencies of 7-day abstinence at 3 months for the two intervention groups. The CPI group experienced a larger decline in depression between the two time points as compared to the UC group. Self-efficacy increased in the CPI group and declined in the UC group, while anxiety increased in the UC group and decreased in the CPI group. The abstinence rate for the CPI group at 3 months was approximately three times higher than the UC group – 15.7 vs. 4.7%, respectively. Significant differences at 3-months between the treatment groups were found only for anxiety (percent difference=7.7%; Cohen’s d=0.24) and self-efficacy (percent difference=11.8%; Cohen’s d=0.31). The difference-in-difference comparisons are presented in column 3 of table 2. Only for self-efficacy was the difference between the two treatment groups significant (percent difference=300%; Cohen’s d= 0.37).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations (SD) and the change scores of hypothesized mediators

| Mediator* | Baseline

|

3-Months

|

Change (3 months-baseline)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC | CPI | UC | CPI | UC | CPI | |||||||

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Depression | 22.05 | (11.27) | 21.60 | (10.94) | 21.78 | (11.23) | 19.94 | (11.11) | −0.26 | (10.19) | −1.66 | (11.28) |

| Anxiety | 43.83 | (12.88) | 43.20 | (13.46) | 44.47 | (13.90) | 41.17 | (13.45) | 0.65 | (13.13) | −2.03 | (14.00) |

| Social Supp. | 34.54 | (7.37) | 34.24 | (7.48) | 34.64 | (7.71) | 34.83 | (7.87) | 0.10 | (7.11) | 0.58 | (6.84) |

| Extrinsic Mot. | 28.08 | (9.56) | 27.71 | (8.67) | 27.48 | (9.23) | 27.40 | (9.22) | −0.60 | (7.91) | −0.31 | (8.29) |

| Intrinsic Mot. | 38.26 | (8.87) | 38.69 | (8.96) | 35.78 | (9.90) | 37.52 | (9.85) | −2.48 | (8.10) | −1.17 | (8.88) |

| Self-Efficacy | 26.03 | (8.38) | 25.13 | (9.35) | 23.29 | (8.68) | 26.21 | (10.37) | −2.74 | (9.79) | 1.08 | (10.61) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| UC | CPI | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Outcome | % | N | % | N | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Smoking abstinence** | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 4.7 | 8 | 15.7 | 28 | ||||||||

| No | 95.3 | 164 | 84.3 | 150 | ||||||||

Higher scores indicate greater levels of each the psychosocial variables;

Biochemically verified (expired carbon monoxide < 7 ppm) and self-reported 7-day abstinence; Bolded results indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

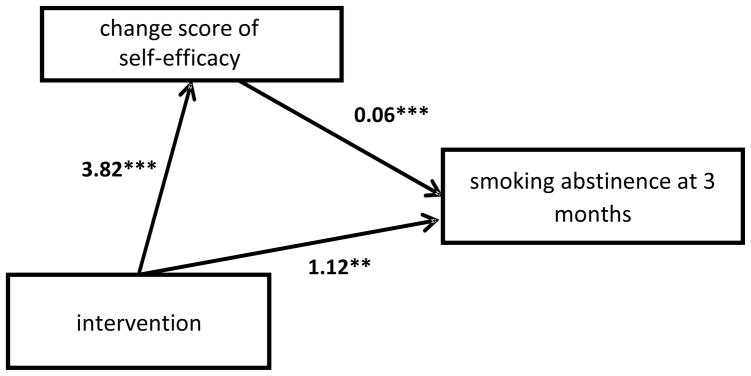

The estimation results of the direct and indirect effects of the mediators, and the intervention on 7-day abstinence are presented in Table 3. The indirect effect of the self-efficacy change score was significant (odds ratio [OR] (exponent of 0.24) =1.27; p=.013). The direct effect of change in self-efficacy on 7-day abstinence was also significant, as was the effect of the intervention on self-efficacy. The intervention effect on 7-day abstinence remained significant and slightly reduced when controlling for change in self-efficacy. Figure 1 presents the paths (a, b, and c) with the parameter values for the mediation model of self-efficacy. The indirect effects of the remaining hypothesized mediators did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Bootstrapped point estimates (b) and con dence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effects of each mediator of intervention group on 7-day abstinence symptoms

| Change score | Indirect effect of intervention on outcome (ab path)

|

Effect of intervention on mediator (a path)

|

Effect of mediator on outcome (b path)

|

Adjusted direct effect of intervention on outcome (c path)

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | p-val. | 95% CI | b | p-val. | 95% CI | b | p-val. | 95% CI | b | p-val. | 95% CI | |||||

| Depression | 0.02 | 0.548 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −1.40 | 0.23 | −3.65 | 0.86 | −0.01 | 0.49 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 1.33 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 2.14 |

| Anxiety | 0.01 | 0.813 | −0.10 | 0.10 | −2.67 | 0.07 | −5.52 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.81 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 1.33 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 2.15 |

| Social Supp. | 0.01 | 0.604 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.49 | 0.52 | −0.98 | 1.95 | 0.02 | 0.39 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 1.33 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 2.15 |

| Extrinsic Mot. | 0.01 | 0.741 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.74 | −1.41 | 1.99 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 1.34 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 2.16 |

| Intrinsic Mot. | 0.04 | 0.317 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 1.30 | 0.15 | −0.48 | 3.09 | 0.03 | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 1.31 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 2.13 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.24 | 0.013 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 3.82 | <0.001 | 1.68 | 5.96 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.12 | <0.01 | 0.29 | 1.96 |

Figure 1.

Mediation results of intervention on smoking abstinence with change scores of self-efficacy from baseline to 3 months.

**=p < 0.01; ***=p < 0.001.

The total effect (the direct effect of the intervention plus the indirect effect) of the intervention due to change in self-efficacy was 1.36 (OR=3.89; p=0.001). The relative magnitude of mediation was assessed by estimating the proportion of the total effect of intervention on 7-day smoking abstinence attributable to change in self-efficacy. This was computed by taking the indirect effect and dividing it by the total effect (0.24 / 1.36), which equaled 0.17. Thus, 17% of the effect of the intervention on 7-day abstinence was attributed to change in self-efficacy. Results (not shown) using the difference of coefficient method produced larger estimates of the indirect and total effects in the model with change in self-efficacy as the mediator, suggesting that our findings may be more conservative compared to other methods (MacKinnon et al., 2007).

4. DISCUSSION

Self-efficacy was identified as a significant treatment mechanism. Specifically, participants in the CPI group (vs. the UC group) reported increases in self-efficacy over the treatment period. This change in self-efficacy was, in turn, associated with higher smoking abstinence rates at the 3-month follow-up. The other potential treatment mechanisms under investigation (i.e., anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, quit motivation, and social support) did not meet the predefined criteria for mediation (MacKinnon, 2008).

Findings are in partial agreement with an earlier study conducted by the research team, in which depressive symptoms, anxiety scores, and self-efficacy were identified as significant treatment mechanisms of a similar cell phone-delivered smoking cessation intervention for PLWH (Vidrine et al., 2006). In both studies, the CPI group had greater increases in self-efficacy and greater decreases in both depressive and anxiety symptoms. While the effects of self-efficacy were consistent in the two studies, the current study did not find a significant mediator effect for depressive or anxiety symptoms. A potential explanation for the contrasting findings may be the differing mediator analytic approach in the two studies. In the current study, a more rigorous approach (MacKinnon, 2008) was used, compared to the approach used in the earlier pilot study. In addition, negative affect scores (depression and anxiety) were elevated beyond clinical levels at baseline and throughout the course of the study, likely due to the multiple personal, medical, life style, and environmental stressors experienced by the population (Gritz et al., 2013). Therefore, failure to find evidence of mediation in this study may be due to ceiling effects. Another possibility is that the cell phone intervention did not adequately address distress in the targeted population of PLWH. Shuter (2014) and colleagues recently reported findings from a pooled analysis that further supports the importance of self-efficacy. Specifically, their findings indicated that post-treatment self-efficacy scores were a significant predictor of abstinence for PLWH enrolled in the treatment trails. Moreover, post-treatment self-efficacy was associated with numerous other predictors of abstinence, including depression, anxiety and substance use (Shuter et al., 2014). The relation of psychological distress and smoking is well-established in the general population (Lawrence et al., 2011; Sung et al., 2011) and in PLWH (Burkhalter et al., 2005; Humfleet et al., 2013; Webb et al., 2009). Thus, findings from the current study and the available literature indicate that future smoking cessation treatments for PLWH should more directly address psychological distress. While the ideal approach (e.g., active screening and referral to existing resources; combining cessation and distress treatment content into an integrated intervention; treating psychological distress prior to providing cessation treatment, etc.) for addressing psychological distress among PLWH who are trying to quit smoking is not yet known, such efforts offer the potential to produce higher long-term abstinence rates.

While we are unaware of other attempts to formally assess the mechanisms of smoking cessation interventions designed for PLWH, other treatment studies with HIV-positive smokers have identified variables that are associated with post-treatment abstinence and/or treatment group membership. For example, in a recent RCT, Moadel and colleagues (2012) found that HIV-positive participants who received an intensive group therapy intervention for smoking were more likely to quit and report higher levels of self-efficacy. Similarly, Ingersol and colleagues (2009) identified self-efficacy (i.e., confidence to avoid smoking in positive affect situations) as a predictor of abstinence for participants who received motivational-based treatment. These previous findings, along with findings from the present study, further support the importance of self-efficacy maintenance for achieving smoking abstinence.

The role of quit motivation is also supported by the existing literature. For example, several RCTs with HIV-positive smokers have identified quit motivation as a significant predator of abstinence (Humfleet et al., 2013; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2009; Moadel et al., 2012). Also of note, efforts to recruit PLWH into a cessation study regardless of motivational state have been positive in terms of short-term smoking outcomes (Cropsey et al., 2013), suggesting that quit motivation is both a malleable and promising treatment mechanism. However, efforts to deliver motivation enhancement interventions have not been overly encouraging in terms of achieving sustained long-term smoking abstinence (Gritz et al., 2013; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2009). Thus, additional efforts are needed to understand the most salient components of quit motivation in PLWH to design more efficacious treatments.

The current study had several limitations. First, the relatively low quit rates observed at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups limited our ability to examine long-term effects. Therefore, we considered the intermediate 3-month outcomes. However, even at 3-months the relatively low abstinence rates may have limited power to detect mediation. We identified only a single treatment mediator, thus we were unable to proceed to multiple mediation analysis. We evaluated the presence of potential bias in our estimated due to missing data by testing for differences at baseline between completers and dropouts, and we did not find statistical differences between the two groups overall, or when stratified by treatment status. Although we cannot be certain about the effects of missing data on the estimates, the non-significant results strengthen our missing at random assumption. In addition, the sample’s demographic profile (e.g., predominately minority, low income, male) may limit generalizability of the findings. Finally, although prospective data was used, temporal relationships should not be assumed.

Despite the limitations, the study adds to the growing literature on smoking cessation treatment for PLWH. The findings further emphasize the important mechanistic function of self-efficacy in promoting smoking cessation. However, additional efforts are required to disentangle the relationships between emotional, distress motivation, and efficacious smoking cessation treatment. Future efforts should also consider the potential effects that HIV disease/treatment may have on smoking cessation. Such in-depth understanding will make possible the development of improved smoking cessation interventions for PLWH.

Highlights.

Mechanisms of a smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected persons are explored.

Changes in self-efficacy, negative affect, motivation, and support are considered.

Seventeen percent of the intervention effect is attributable to self-efficacy.

Change in self-efficacy is a mediator of the smoking cessation intervention.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding Sources:

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, [R01CA097893] awarded to Ellen R. Gritz, and [P30CA16672] awarded to Ronald DePinho.

Footnotes

Contributors:

All authors of this manuscript have directly participated in the design and/or execution of the study. All have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

This trial has been registered at clinicaltrails.gov [NCT00502827]

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allison PD. Change scores as dependent variables in regression analysis. In: Clogg, Clogg CC, editors. Sociological Methodology Basil. Blackwell; Oxford: 1990. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- AMA. Health care needs of gay men and lesbians in the United States. Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. JAMA. 1996;275:1354–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Johnson EO. Predicting smoking cessation and major depression in nicotine-dependent smokers. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1122–1127. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KK, Wewers ME, Ferketich AK, Diaz P. Tobacco use and cessation in HIV-infected individuals. Clin Chest Med. 2013;34:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M, Furman A, Hoffman M, Marmor S, Blum A, Yust I. Lung cancer in patients with HIV infection: is it AIDS-related? HIV Med. 2004;5:110–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter JE, Springer CM, Chhabra R, Ostroff JS, Rapkin BD. Tobacco use and readiness to quit smoking in low-income HIV-infected persons. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:511–522. doi: 10.1080/14622200500186064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social Support: Theory, Research, And Applications. Martinus Nijhoff; The Hague, The Netherlands: 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropsey KL, Hendricks PS, Jardin B, Clark CB, Katiyar N, Willig J, Mugavero M, Raper JM, Saag M, Carpenter MJ. A pilot study of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment (SBIRT) in non-treatment seeking smokers with HIV. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2541–2546. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crothers K, Griffith TA, McGinnis KA, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Leaf DA, Weissman S, Gibert CL, Butt AA, Justice AC. The impact of cigarette smoking on mortality, quality of life, and comorbid illness among HIV-positive veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1142–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry S, Wagner EH, Grothaus LC. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:310–316. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W. The relationship between tobacco use, substance-use disorders and mental health: results from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:225–234. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz T, Chu SY, Buehler JW, Boyd D, Checko PJ, Conti L, Davidson AJ, Hermann P, Herr M, Levy A. Socioeconomic differences among people with AIDS: results from a Multistate Surveillance Project. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels EA, Brock MV, Chen J, Hooker CM, Gillison M, Moore RD. Elevated incidence of lung cancer among HIV-infected individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1383–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman C, Anderson R. Cigarette smoking and mechanisms of susceptibility to infections of the respiratory tract and other organ systems. J Infect. 2013;67:169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JG, Minkoff H, Schneider MF, Gange SJ, Cohen M, Watts DH, Gandi M, Mocharnuk RS, Anastos K. Association of cigarette smoking with HIV prognosis among women in the HAART era: a report from the women’s interagency HIV study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1060–1065. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NJ, Curry SJ, Dorfman SF, Froelicher ES, Goldstein MG, Healton CG, Henderson PN, Heyman RB, Koh HK, Kottle TE, Lando HA, Mecklenburg RE, Mermelstein RJ, Mullen PD, Orleans CT, Robinson L, Stitzer ML, Tommasello AC, Villejo L, Wewers ME. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Public Health Service (PHS); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood GL, Paul JP, Pollack LM, Binson D, Catania JA, Chang J, Humfleet G, Stall R. Tobacco use and cessation among a household-based sample of us urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:145–151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.021451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Danysh HE, Fletcher FE, Tami-Maury I, Fingeret MC, King RM, Arduino RC, Vidrine DJ. Long-term outcomes of a cell phone-delivered intervention for smokers living with HIV/AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;4:608–615. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN. Reframing HIV prevention for gay men in the United States. Am Psychol. 2010;65:752–763. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.65.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, Larsen C, Pedersen G, Pedersen C, Gerstoft J, Nordestgaard BG, Obel N. Mortality attributable to smoking among hiv-1-infected individuals: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:727–734. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo K, Tsutsumi A, Kawachi I, Kawakami N. What accounts for the relationship between social class and smoking cessation? Results of a path analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humfleet GL, Hall SM, Delucchi KL, Dilley JW. A randomized clinical trial of smoking cessation treatments provided in hiv clinical care settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1436–1445. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll KS, Cropsey KL, Heckman CJ. A test of motivational plus nicotine replacement interventions for HIV positive smokers. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9334-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Non-specific psychological distress, smoking status and smoking cessation: United States National Health Interview Survey 2005. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:256. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazev A, Vidrine D, Arduino R, Gritz E. Increasing access to smoking cessation treatment in a low-income, HIV-positive population: the feasibility of using cellular telephones. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:281–286. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001676314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifson AR, Lando HA. Smoking and HIV: prevalence, health risks, and cessation strategies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, van den Berg-Wolf M, Labriola AM, Read TR. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1896–1903. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson EE, Stanton CA, Papandonatos GD, Shadel WG, Stein M, Tashima K, Flanigan T, Morrow K, Neighbors C, Niaura R. Motivation and patch treatment for HIV+ smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104:1891–1900. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction To Statistical Mediation Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Taylor & Francis Group; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Brown CH, Wang W, Hoffman JM. The intermediate endpoint effect in logistic and probit regression. Clin Trials. 2007;4:499–513. doi: 10.1177/1740774507083434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguez-Burbano MJ, Burbano X, Ashkin D, Pitchenik A, Allan R, Pineda L, Rodriguez N, Shor-Posner G. Impact of tobacco use on the development of opportunistic respiratory infections in HIV seropositive patients on antiretroviral therapy. Addict Biol. 2003;8:39–43. doi: 10.1080/1355621031000069864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People To Change Addictive Behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Moadel AB, Bernstein SL, Mermelstein RJ, Arnsten JH, Dolce EH, Shuter J. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored group smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:208–215. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182645679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscou-Jackson G, Commodore-Mensah Y, Farley J, DiGiacomo M. Smoking-cessation interventions in people living with HIV infection: a systematic review. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donahue W, Fisher JE, Hayes SC, editors. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Applying Empirically Supported Techniques in Your Practice. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Palella FJ, Jr, Phair JP. Cardiovascular disease in HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:266–271. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328347876c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Shuter J, Moadel AB, Kim RS, Weinberger AH, Stanton CA. Self-Efficacy to Quit in HIV-Infected Smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:1527–1531. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD, Thiebaut R, Weber R, Law M, Montforte A, Kirk O, Friis-Moller N, Phillips A, Reiss P, Reiss P, El Sadr W, Pradier C, Worm SW. Factors associated with specific causes of death amongst HIV-positive individuals in the D:A:D Study. AIDS. 2010;24:1537–1548. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch R, Lushene RE. STAI Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sung HY, Prochaska JJ, Ong MK, Shi Y, Max W. Cigarette smoking and serious psychological distress: a population-based study of California adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:1183–1192. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Diclemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: an integrative model. Addict Behav. 1990;15:271–283. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidrine DJ, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. Impact of a cell phone intervention on mediating mechanisms of smoking cessation in individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(Suppl 1):S103–108. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidrine DJ, Arduino RC, Lazev AB, Gritz ER. A randomized trial of a proactive cellular telephone intervention for smokers living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2006;20:253–260. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198094.23691.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidrine DJ, Marks RM, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. Efficacy of cell phone-delivered smoking cessation counseling for persons living with HIV/AIDS: 3-month outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:106–110. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb MS, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC. Medication adherence in HIV-infected smokers: the mediating role of depressive symptoms. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:94–105. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Borland R, Rodgers A, Gu Y. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006611. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]