Abstract

Recent studies have conferred that the RAD51C and RAD51D genes, which code for the essential proteins involved in homologous recombination, are ovarian cancer (OC) susceptibility genes that may explain genetic risks in high-risk patients. We performed a mutation analysis in 171 high-risk BRCA1 and BRCA2 negative OC patients, to evaluate the frequency of hereditary RAD51C and RAD51D variants in Czech population. The analysis involved direct sequencing, high resolution melting and multiple ligation-dependent probe analysis. We identified two (1.2%) and three (1.8%) inactivating germline mutations in both respective genes, two of which (c.379_380insG, p.P127Rfs*28 in RAD51C and c.879delG, p.C294Vfs*16 in RAD51D) were novel. Interestingly, an indicative family cancer history was not present in four carriers. Moreover, the ages at the OC diagnoses in identified mutation carriers were substantially lower than those reported in previous studies (four carriers were younger than 45 years). Further, we also described rare missense variants, two in RAD51C and one in RAD51D whose clinical significance needs to be verified. Truncating mutations and rare missense variants ascertained in OC patients were not detected in 1226 control samples. Although the cumulative frequency of RAD51C and RAD51D truncating mutations in our patients was lower than that of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, it may explain OC susceptibility in approximately 3% of high-risk OC patients. Therefore, an RAD51C and RAD51D analysis should be implemented into the comprehensive multi-gene testing for high-risk OC patients, including early-onset OC patients without a family cancer history.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) it is the most lethal gynecologic malignancy, though it represents only 3% of female cancers worldwide. Its unfavorable prognosis related to a high percentage of late-stage diagnosis ranks OC to the fourth place among the most common cancer-related cause of death in female population [1]. Its incidence in the Czech Republic is 23/100,000 individuals and mortality amounts to 15/100,000 individuals [2].

The most important risk factor is a family OC history. It has been supposed that hereditary predisposition accounts for at least 10% of OC cases [3]. Therefore, the identification of woman carrying the pathogenic mutations in OC-susceptibility genes is an important task enabling tailored OC prevention in high-risk population. The majority of hereditary OC (HOC) cases are also associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (BC) and the most frequent pathogenic mutations in hereditary breast and/or ovarian (HBOC) cancer families affect the BRCA1 gene and to a lesser extent also BRCA2 [4]. Both genes play an important role in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DDSB). Recently, additional genes were described as associated with HOC, among them the RAD51 paralogs RAD51C and RAD51D.

Both genes code for proteins involved in genome stability maintenance and they participate in the homologous recombination-mediated DDSB repair [5,6]. Initial studies reported the RAD51C gene (MIM:602774) as another Fanconi anemia (FA) gene designated as FANCO because its biallelic germline mutations were found in a patient with FA-like phenotype corresponding to complementation group O [7]. The pioneering work of Meindl et al. showed that RAD51C is an OC susceptibility gene with a mutation frequency of 1.3% in HBOC patients [8]. Since then, further studies have proved the role of the RAD51C gene in OC development in up to 2.5% of high-risk HBOC families [9,10,11,12] including rare large genomic rearrangements [13].

A study by Loveday et al. reported that germline mutations in the RAD51D gene (MIM:602954) confer susceptibility to OC in 0.9% of HBOC families (predominantly with more than one case of OC) and estimated the relative risk (RR) at 6.3 for OC and 1.32 for BC [14]. Several other studies have confirmed its role in OC susceptibility [15,16,17,18].

While individually rare, together all the moderate-penetrance genes can contribute to a significant proportion of OC risk; however, their frequencies vary in different populations [19]. The aim of our study was to determine the frequency of germline mutations in RAD51C and RAD51D among high-risk OC Czech patients negatively tested for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.

Methods

Patients

We analyzed 171 DNA samples (obtained from peripheral blood) from BRCA1 and BRCA2 negative OC patients collected at our institute between 2000 and 2013. They belonged to either a familial group (N = 62) or a group without family cancer history (N = 109; Table 1) [20]. The control group consisted of anonymized DNA samples obtained from 1,226 individuals including 756 non-cancer individuals and 470 blood donors, as described previously [21,22].

Table 1. Criteria for the enrollment of high-risk BRCA1- and BRCA2-negative individuals in this study and number of identified mutations in each group.

| Inclusion criteria: | Patients (N) | RAD51C mut (N) | RAD51D mut (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familial cases (N = 62) | ||||

| HBOC families: | ||||

| - probands with OC only | 41 | 1 | (1) | |

| - probands with both OC and BC | 9 | - | - | |

| HOC families (OC ≥ 2) | 12 | - | - | |

| Cases without family cancer history (N = 109) | ||||

| Tumor duplicity (OC and BC) | 22 | - | - | |

| OC diagnosed at < 60 y/o or high-grade adenocarcinoma | 87 | 1 (2) | 3 | |

| Total | ||||

| 171 | 2 (2) | 3 (1) | ||

BC—breast cancer; HBOC—hereditary breast and ovarian cancer; HOC—hereditary ovarian cancer; OC—ovarian cancer; y/o—years old. Number of rare missense variants are in brackets.

All patients and controls were of Central European descent of Czech origin from the Prague region. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the General University Hospital in Prague and all participants gave their written informed consent with the use of stored DNA/RNA samples for research purposes.

Mutation analysis

All individual coding exons (with intron-exon boundaries) separated by large intronic regions in the RAD51C gene were PCR-amplified (primers are listed in S1 Table) and analyzed by a high resolution melting (HRM) analysis on the Light Cycler 480 (Roche) using an HOT FirePol EvaGreen HRM Mix (Solis BioDyne) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Variants in samples with an aberrant melting profile were confirmed by direct sequencing from separate PCR reactions using the BigDye v3.1 on ABI3130 (Applied Biosystems).

All coding exons (including intron-exon boundaries) that form four exonic clusters of the RAD51D gene were amplified by PCR and analyzed by direct sequencing (PCR and sequencing primers are listed in S1 Table).

All exons with the identified mutations were screened in 1,226 control samples by an HRM analysis and variant samples were confirmed by sequencing.

Detection of large genomic rearrangements (LGRs)

The P260-A1 Kit was used for a multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis in RAD51C according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The amplified products were separated on ABI3130 and analyzed by the MRC Coffalyser software (MRC Holland). The MLPA kit for RAD51D analysis was not available from any supplier at the time of the analysis.

cDNA analysis

In order to determine the effect of intronic variant c.1026+5_1026+7delGTA flanking to intron-exon boundary in RAD51C we performed a cDNA-based analysis. The total RNA isolated from venous blood was reverse transcribed into the cDNA using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR fragment spanning the involved region was amplified (primers are in S1 Table). PCR product containing wild-type and aberrant fragments was sequenced in order to characterize aberrant splicing variant.

In silico analysis

The pathogenicity of missense variants was assessed using the SIFT, PolyPhen, Align GVGD, and CADD score tools as described previously [21,22]. Frequencies of identified variants were ascertained in NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP; https://esp.gs.washington.edu/drupal/) and 1000 Genomes (http://www.1000genomes.org/) databases.

Results

Pathogenic mutations leading to truncation of protein products were identified in five out of 171 (3%) high-risk OC patients, two (1.2%) in RAD51C and three (1.8%) in RAD51D (Table 2). Two pathogenic alterations were novel. No LGR was found in the RAD51C gene, but we could not exclude a presence of LGRs in the RAD51D gene that was not analyzed because MLPA kit was unavailable in the time of the analysis. None of the identified alterations was found in the 1,226 non-cancer controls. The age at diagnosis and the family history of cancers in the mutations’ carriers are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Mutations identified in the RAD51C and RAD51D genes in analyzed high-risk patients.

| Patient No. | Exon | cDNA change | Protein change | OC/other cancers; (age at diagnosis) | Histology | Grade | Stage | Cancer in family; (age at diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAD51C | ||||||||

| – truncating mutations | ||||||||

| 218 | 2 | c.379_380insG + | p.P127Rfs*28 | OC (25) | mucinous adenocarcinoma | G3 | IC | MS-OC (56), FM-BC (60) |

| 1273 | 8+ | c.1026+5_1026+7delGTA | p.R322Sfs*22 | OC (27), Endometrial (34) | serous adenocarcinoma | low-grade | MF-Leukemia (65), FF-Gastric ca (68) | |

| – rare missense mutations | ||||||||

| 1418 | 4 | c.641G>A + | p.R214H | OC (28), Colon ca (28) | serous cystadenoma, borderline malignancy | — | IIIC | negative |

| 1607 | 7 | c.947A>G + | p.H316R | OC (55), BC (69), Lung ca (72) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | negative |

| RAD51D | ||||||||

| – truncating mutations | ||||||||

| 142 | 8 | c.694C>T | p.R232* | OC (37) | serous adenocarcinoma | high-grade | IIIC | negative |

| 2115 | 8 | c.694C>T | p.R232* | OC (43) | serous adenocarcinoma | high-grade | IIIC | negative |

| 1119 | 9 | c.879delG + | p.C294Vfs*16 | OC (66) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | D-Thyroid ca (44) & Endometrial ca (44) |

| – rare missense mutation | ||||||||

| 107 | 7 | c.629C>T | p.A210V | OC (33) | adenocarcinoma | n.a. | IIIA | FM-BC (n.a.), FS1-BC (56), FS2-Colon ca (47), FF-Prostate ca (72) |

+—novel variants;

B—brother; BC—breast cancer; D—daughter; F—father; FF—father’s father; FM—father’s mother; FS—father’s sister; M—mother; MF—mother’s father; n.a.—not available; OC—ovarian cancer.

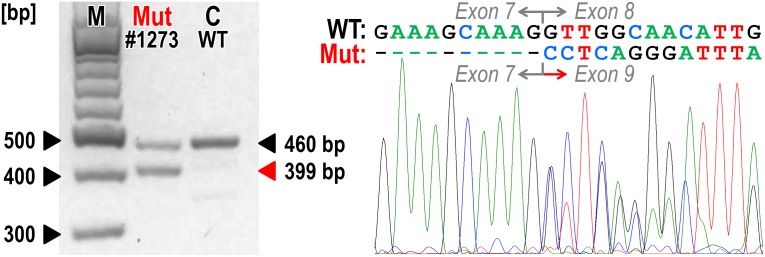

A novel c.379_380insG (p.P127Rfs*28) variant in RAD51C was found in a young OC patient who died 12 months after a diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma. Another RAD51C truncating variant was a splice-site alteration, c.1026+5_1026+7delGTA, identified in a patient who developed endometrial carcinoma seven years after a diagnosis of ovarian serous adenocarcinoma. The pathogenic potential of this alteration was demonstrated by the cDNA analysis that revealed aberrant exon 8 skipping, that resulted in frame-shift and premature termination of translation product (p.R322Sfs*22; Fig 1). This variant was previously reported once in a control and a patient, respectively, by Loveday et al. and in a study by Golmard et al. [10,11].

Fig 1. cDNA analysis of patient No.1273 uncovered with an intronic variant c.1026+5_1026+7delGTA causing RAD51C out-of-frame exon 8 skipping.

The electrophoresis (left) of PCR products amplified with primers located in exon 5 and 3’ UTR sequence (S1 Table) shows two products in a patient No.1273 compared to a wild-type control (C) sample. Sequencing chromatogram of the patient’s PCR product shows the presence of aberrantly spliced mRNA with exon 8 skipping.

The only truncating mutation described recurrently in our study was c.694C>T (p.R232*) in RAD51D, found in two unrelated young OC patients with serous adenocarcinoma and no family cancer history. The earlier diagnosed patient died of OC dissemination 10 years after the diagnosis. This variant was previously described in Spanish and American HBOC patients [18,16]. A novel RAD51D mutation, c.879delG (p.C294Vfs*16), was found in an OC patient with a daughter suffering from BC and OC duplicity.

Besides the truncating variants, we found three rare missense variants (Table 2). The c.641G>A (p.R214H) mutation in RAD51C was recently identified in a BC female of African origin [12] and described as a low risk variant based on her family history that is in accord with software predictions. The second rare missense variant c.947A>G (p.H316R) was novel; however, both these alterations in RAD51C were predicted as non-pathogenic. The only rare variant- c.629C>T (p.A210V)—in RAD51D was described previously [18] and was predicted as pathogenic (Table 2).

Other detected sequence variants presented in a dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/) or HGMD (https://portal.biobase-international.com/hgmd/pro/start.php) databases as polymorphisms are listed in S3 Table.

Discussion

We identified germline truncating mutations in the RAD51C and RAD51D genes in 1.2% and 1.8% of analyzed high-risk individuals, respectively, which is consistent with previous studies [23,24]. Our study provides further evidence that both genes confer a limited but clinically remarkable proportion of OC susceptibility.

First studies reported deleterious truncating mutations in the RAD51C and RAD51D genes predominantly in HBOC families with two or more OC cases [8,14]. However, we found the majority (four out of five clearly deleterious mutations; Table 2) in a subgroup of 109 BRCA1 and BRCA2 negative OC patients without BC or OC family history. This is in agreement with later studies which identified RAD51C and RAD51D mutations in an unselected population of OC patients [25,16]. These results suggest that comprehensive genetic testing of the RAD51C and RAD51D genes in OC patients should not be limited only to high-risk OC patients with an apparent family history, and an analysis of all OC patients should be considered irrespectively to the family cancer history and age of onset [26].

The mean ages of OC onset for women with RAD51C and RAD51D mutations published in previous studies were 60 years for RAD51C (reviewed in [23]) and 56.6 years for RAD51D (S4 Table). Sopik et al. proposed the preventive surgery to be delayed until after natural menopause. Nevertheless, in our study the mean ages of OC onset in carriers of truncating variants were 26.0 years for RAD51C (25 and 27 years, respectively) and 48.7 years for RAD51D (37, 43, and 66 years, respectively). While a small number of mutation carriers might influence this observation, we suppose that the fact that four of five carriers of pathogenic mutations in the RAD51C and RAD51D genes were premenopausal women younger than 45 years might be of clinical importance. Hence, further studies of carriers in both genes are necessary to estimate the clinical recommendations for risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RR-BSO) and until then, the earliest onset of OC in the family should be taken into account. Recently, Baker et al. reported RR-BSO in a 39 years old female BC patient carrying RAD51D mutation from family with multiple BC (but no OC) cases [24].

In our study, only one proband, carrying the pathogenic RAD51C mutation, displayed family cancer history that included OC and BC cases. Since previous studies reported no increased risk of BC for the carriers, later studies described few RAD51C and RAD51D truncating mutations in BC only families [13,27,28,18,24]. Although these mutations seem to be very rare in BC patients, they are probably responsible for certain BC predisposition. The pedigrees of mutation carriers include other cancer cases (endometrial, leukemia, thyroid), whose association with the mutations should be further analyzed in detail.

We also identified three rare missense alterations in both genes (Table 2, S2 Table). Only the c.629C>T, p.A210V rare missense variant in the RAD51D gene was predicted to be deleterious consistently in all used software prediction tools. However, its pathogenicity cannot be confirmed without further segregation and/or functional analyses. Unfortunately, we were not able to perform a co-segregation analysis in other family relatives.

The penetrance for mutations in moderate penetrance genes is not easy to estimate [29]. Initially, Meindl et al. reported a complete segregation of RAD51C mutations in HBOC families [8]. Further studies estimated the relative risk (RR) of OC for mutation carriers in RAD51C (RR = 5.9) and RAD51D (RR = 6.3) [10,14]. Pelttari et al. discovered an odds ratio (OR) for Finnish founder mutations in each gene in an unselected population to be 6.3 and 7.1, respectively [30,15]. These data suggest that the OC risk exceeds the threshold for moderate penetrance genes in RAD51C and RAD51D mutations carriers and both genes have clinical significance for diagnostic testing and preventive steps for the carriers involving both OC and BC management. Further studies and meta-analyses of published data from various populations worldwide are required to estimate the penetrance in RAD51C and RAD51D mutation carriers convincingly.

The clinical utility of the identification of RAD51C and RAD51D mutation carriers is not limited to the prediction of cancer susceptibility only. Both proteins are involved in DNA damage signaling and DDSB repair functionally co-operating with BRCA1 and BRCA2 in processes of homologous recombination (HR). A failure of this repair pathway that could be expected in cancer patients carrying germline pathogenic mutations in RAD51C and RAD51D sensitizes cancer cells to PARP inhibitors; therefore, patients carrying germline RAD51C and RAD51D mutations may benefit from this therapy [14].

In conclusion, we described novel pathogenic variants in RAD51C and RAD51D and showed that truncating mutations in both genes could be found in 3% of high-risk Czech OC patients. Our results indicate that the onset of OC in mutation carriers could be younger than expected. We propose that mutation analysis of RAD51C and RAD51D should be implemented into the comprehensive multi-gene panel testing in high-risk OC patients. However, further studies in various populations can help to improve the estimates of the clinical impact for germline mutation carriers and allow the determination of appropriate screening, follow-up, or prevention strategies.

Supporting Information

Summary of PCR primers used for sequencing, cDNA and HRM analyses.

(DOCX)

Prediction analysis of identified rare missense variants in the RAD51C and RAD51D genes and the frequency of these variants in exome sequencing and 1000 genomes projects.

(DOCX)

Previously described alterations (polymorphisms, intronic variants) found in our study.

(DOCX)

Ages of onset of 21 OC patients and 15 BC patients carrying RAD51D mutations in studies published so far.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to the memory of our colleague and friend, Petr Pohlreich, who passed away when the manuscript was being written.

We wish to thank Marie Epsteinova and Marketa Dostalova for their excellent technical support and patients and their families for contribution in this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Internal Grant Agency, Ministry of Health, Czech Republic, NT13343, (http://www.mzcr.cz/Cizinci/); PP, Charles University in Prague, PRVOUK-P27/LF1/1, (http://www.cuni.cz/UKEN-1.html); MJ, Charles University in Prague, SVV-UK 3362-2014, (http://www.cuni.cz/UKEN-1.html); PB. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Weissman SM, Weiss SM, Newlin AC (2012) Genetic testing by cancer site: ovary. Cancer J 18: 320–327. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31826246c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epidemiology of malignant tumors in the Czech Republic. Available: http://www.svod.cz. Accessed 18 December 2014.

- 3. Oosterwijk JC, de Vries J, Mourits MJ, de Bock GH (2014) Genetic testing and familial implications in breast-ovarian cancer families. Maturitas 78: 252–257. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramus SJ, Harrington PA, Pye C, DiCioccio RA, Cox MJ, Garlinghouse-Jones K, et al. (2007) Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to inherited ovarian cancer. Hum Mutat 28: 1207–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Somyajit K, Subramanya S, Nagaraju G (2010) RAD51C: a novel cancer susceptibility gene is linked to Fanconi anemia and breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 31: 2031–2038. 10.1093/carcin/bgq210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Masson JY, Tarsounas MC, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Shah R, McIlwraith MJ, et al. (2001) Identification and purification of two distinct complexes containing the five RAD51 paralogs. Genes Dev 15: 3296–3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaz F, Hanenberg H, Schuster B, Barker K, Wiek C, Erven V et al. (2010) Mutation of the RAD51C gene in a Fanconi anemia-like disorder. Nat Genet 42: 406–409. 10.1038/ng.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meindl A, Hellebrand H, Wiek C, Erven V, Wappenschmidt B, Niederacher D et al. (2010) Germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees establish RAD51C as a human cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet 42: 410–414. 10.1038/ng.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coulet F, Fajac A, Colas C, Eyries M, Dion-Miniere A, Rouzier R et al. (2013) Germline RAD51C mutations in ovarian cancer susceptibility. Clin Genet 83: 332–336. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01917.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loveday C, Turnbull C, Ruark E, Xicola RM, Ramsay E, Hughes D et al. (2012) Germline RAD51C mutations confer susceptibility to ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 44: 475–476. 10.1038/ng.2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Golmard L, Caux-Moncoutier V, Davy G, Al Ageeli E, Poirot B, Tirapo C et al. (2013) Germline mutation in the RAD51B gene confers predisposition to breast cancer. BMC Cancer 13: 484 10.1186/1471-2407-13-484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tung N, Battelli C, Allen B, Kaldate R, Bhatnagar S, Bowles K et al. (2014) Frequency of mutations in individuals with breast cancer referred for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing using next-generation sequencing with a 25-gene panel. Cancer 121: 25–33. 10.1002/cncr.29010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schnurbein G, Hauke J, Wappenschmidt B, Weber-Lassalle N, Engert S, Hellebrand H et al. (2013) RAD51C deletion screening identifies a recurrent gross deletion in breast cancer and ovarian cancer families. Breast Cancer Res 15: R120 10.1186/bcr3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loveday C, Turnbull C, Ramsay E, Hughes D, Ruark E, Frankum JR et al. (2011) Germline mutations in RAD51D confer susceptibility to ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 43: 879–882. 10.1038/ng.893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pelttari LM, Kiiski J, Nurminen R, Kallioniemi A, Schleutker J, Gylfe A et al. (2012) A Finnish founder mutation in RAD51D: analysis in breast, ovarian, prostate, and colorectal cancer. J Med Genet 49: 429–432. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wickramanayake A, Bernier G, Pennil C, Casadei S, Agnew KJ, Stray SM et al. (2012) Loss of function germline mutations in RAD51D in women with ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 127: 552–555. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thompson ER, Rowley SM, Sawyer S, kConfab, Eccles DM, Trainer AH et al. (2013) Analysis of RAD51D in ovarian cancer patients and families with a history of ovarian or breast cancer. PLoS One 8: e54772 10.1371/journal.pone.0054772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gutierrez-Enriquez S, Bonache S, de Garibay GR, Osorio A, Santamarina M, Ramón y Cajal T et al. (2014) About 1% of the breast and ovarian Spanish families testing negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2 are carriers of RAD51D pathogenic variants. Int J Cancer 134: 2088–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Janatova M, Kleibl Z, Stribrna J, Panczak A, Vesela K, Zimovjanova M et al. (2013) The PALB2 gene is a strong candidate for clinical testing in BRCA1- and BRCA2-negative hereditary breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22: 2323–2332. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0745-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pohlreich P, Zikan M, Stribrna J, Kleibl Z, Janatova M, Kotlas J et al. (2005) High proportion of recurrent germline mutations in the BRCA1 gene in breast and ovarian cancer patients from the Prague area. Breast Cancer Res 7: R728–R736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kleibl Z, Novotny J, Bezdickova D, Malik R, Kleiblova P, Foretova L et al. (2005) The CHEK2 c.1100delC germline mutation rarely contributes to breast cancer development in the Czech Republic. Breast Cancer Res Treat 90: 165–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kleibl Z, Havranek O, Hlavata I, Novotny J, Sevcik J, Pohlreich P et al. (2009) The CHEK2 gene I157T mutation and other alterations in its proximity increase the risk of sporadic colorectal cancer in the Czech population. Eur J Cancer 45: 618–624. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sopik V, Akbari MR, Narod SA (2014) Genetic testing for RAD51C mutations: in the clinic and community. Clin Genet: In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baker JL, Schwab RB, Wallace AM, Madlensky L (2015) Breast Cancer in a RAD51D Mutation Carrier: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin Breast Cancer 15: e71–e75. 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walsh T, Lee MK, Casadei S, Thornton AM, Stray SM, Pennil C et al. (2010) Detection of inherited mutations for breast and ovarian cancer using genomic capture and massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 12629–12633. 10.1073/pnas.1007983107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pennington KP, Swisher EM (2012) Hereditary ovarian cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Gynecol Oncol 124: 347–353. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rashid MU, Muhammad N, Faisal S, Amin A, Hamann U (2014) Deleterious RAD51C germline mutations rarely predispose to breast and ovarian cancer in Pakistan. Breast Cancer Res Treat 145: 775–784. 10.1007/s10549-014-2972-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blanco A, Gutierrez-Enriquez S, Santamarina M, Montalban G, Bonache S, Balmaña J et al. (2014) RAD51C germline mutations found in Spanish site-specific breast cancer and breast-ovarian cancer families. Breast Cancer Res Treat 147: 133–143. 10.1007/s10549-014-3078-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stratton MR, Rahman N (2008) The emerging landscape of breast cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet 40: 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pelttari LM, Heikkinen T, Thompson D, Kallioniemi A, Schleutker J, Holli K et al. (2011) RAD51C is a susceptibility gene for ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet 20: 3278–3288. 10.1093/hmg/ddr229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of PCR primers used for sequencing, cDNA and HRM analyses.

(DOCX)

Prediction analysis of identified rare missense variants in the RAD51C and RAD51D genes and the frequency of these variants in exome sequencing and 1000 genomes projects.

(DOCX)

Previously described alterations (polymorphisms, intronic variants) found in our study.

(DOCX)

Ages of onset of 21 OC patients and 15 BC patients carrying RAD51D mutations in studies published so far.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.