The crystal structure of the LRR domain of PP32A has been solved to 1.6 Å resolution.

Keywords: PP32A LRR domain structure, tumour suppressor, SET complex

Abstract

Acidic leucine-rich nuclear phosphoprotein 32A (PP32A) is a tumour suppressor whose expression is altered in many cancers. It is an apoptotic enhancer that stimulates apoptosome-mediated caspase activation and also forms part of a complex involved in caspase-independent apoptosis (the SET complex). Crystals of a fragment of human PP32A corresponding to the leucine-rich repeat domain, a widespread motif suitable for protein–protein interactions, have been obtained. The structure has been refined to 1.56 Å resolution. This domain was previously solved at 2.4 and 2.69 Å resolution (PDB entries 2je0 and 2je1, respectively). The new high-resolution structure shows some differences from previous models: there is a small displacement in the turn connecting the first α-helix (α1) to the first β-strand (β1), which slightly changes the position of α1 in the structure. The shift in the turn is observed in the context of a new crystal packing unrelated to those of previous structures.

1. Introduction

Acidic leucine-rich nuclear phosphoprotein 32A (PP32A) contains an N-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain. PP32A acts as a tumour suppressor and its expression is altered in many tumours. It favours the activation of caspase 9 through the apoptosome (Pan et al., 2009 ▶) and is also implicated in caspase-independent apoptosis since it is a member of the SET complex (Lieberman, 2010 ▶; Beresford et al., 2001 ▶). The Set oncoprotein gives name to the SET complex, which translocates to the nucleus in response to reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial damage.

In addition, PP32A is involved in other activities such as modulating histone acetylation and transcription as it forms part of the INHAT (inhibitor of histone acetyltransferases) complex, where in association with the Set oncoprotein (Muto et al., 2007 ▶) it inhibits the histone-acetyltranferase activity of p300/CBP (CREB-binding protein) and p300/CBP-associated factor by histone masking (Seo et al., 2002 ▶). PP32A is also implicated in the inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A (Li et al., 1996 ▶). PP32A also participates in other biochemical processes such as regulation of mRNA trafficking and stability by its association with HuR (Hu-antigen R), which increases the stability of mRNA binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) region (Mazroui et al., 2008 ▶)

PP32A has three differentiated regions: an N-terminal LRR domain and a central region which connects the LRR domain to a highly acidic C-terminal domain. The LRR domain has a curved shape that has been shown to be appropriate for building protein–protein interaction modules (Bella et al., 2008 ▶). This domain is not only important because it might be responsible for many PP32A interactions, but also because several LRR domain crystal structures exhibit their ligand-binding domain in this concave surface.

Our high-resolution human PP32A LRR domain structure (PDB entry 4xos) shows some differences compared with previously reported structures (Huyton & Wolberger, 2007 ▶), including some modifications at the end of helix α1 and the loop connecting it to the β1 strand. This change is involved in the generation of a totally different crystal packing. A chloride ion is located in the vicinity, interacting with residues towards the end of the α1–β1 turn and the initial β1 residues.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

A fragment of the gene encoding human PP32A (protein residues 1–149) was cloned into a modified version of the pET-28a vector (Table 1 ▶). This construct was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus RIPL cells (Invitrogen) for 3 h at 303 K following induction with 1 mM IPTG when the cell density had reached a value of between 0.6 and 0.8. The cells were harvested, washed with PBS and stored at −80°C until use.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | Human |

| DNA source | cDNA library |

| Forward primer | GCGCATATGGAGATGGGCAGACGGATTC |

| Reverse primer | CGCCTCGAGTTAGTCATAGCCGTCGAGATA |

| Expression vector | pET-28a |

| Expression host | E. coli BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus RIPL |

| Complete amino-acid sequence of the construct produced | MGSSHHHHHHSSGLEVLFQGPHMEMGRRIQLELRNRTPFDVKELVLDNSRSNEGKLEGLTDEFEELEFLSTINVGLTSIANLPKLNKLKKLELSDNRVSGGLEVLAEKCPNLTHLNLSGNKIKDLSTIEPLKKLENLKSLDLFNCEVTNLNDYRENVFKLLPQLTYLDGYD |

For purification, the cells were sonicated with a lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton X-100, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME). To remove cell debris, the lysate was centrifuged prior to loading onto a 5 ml chelating nickel HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with six column volumes of buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 350 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 2 mM BME) and the protein was eluted using a gradient to buffer B (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 350 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 500 mM imidazole, 2 mM BME). These buffers were selected from Thermofluor stability assay results (Boivin et al., 2013 ▶; Reinhard et al., 2013 ▶). Elution fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and the fractions containing PP32 were treated overnight at 4°C with recombinant human rhinovirus 3C protease fused to glutatione S-transferase. After digestion, the sample was loaded onto a Sepharose column covalently linked to glutathione in order to remove the protease. The sample was concentrated and injected onto a Superdex 200 16/60 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM BME.

2.2. Crystallization

Plate-like crystals with approximate dimensions of 0.2 × 0.6 × 0.7 mm were grown by mixing 0.4 µl protein solution at 300 µM and 0.4 µl reservoir solution (20% PEG 3000, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 0.2 M NaCl) at 294 K using the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method (Table 2 ▶). Crystals appeared within one week.

Table 2. Crystallization conditions.

| Method | Sitting-drop vapour diffusion |

| Plate type | 96-well plate |

| Temperature (K) | 294 |

| Protein concentration (M) | 300 |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 20mM TrisHCl pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM BME |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 20% PEG 3000, 0.1M HEPES pH 7.5, 0.2M NaCl |

| Volume and ratio of drop | 0.4l (1:1) |

| Volume of reservoir (l) | 0.4 |

2.3. Data collection and processing

One- to two-week-old crystals were flash-cryocooled with liquid nitrogen without the use of any additional cryoprotectant. Diffraction data were collected from the crystals at 100 K on the XALOC beamline at the ALBA synchrotron, Barcelona, Spain. A complete data set was collected to 1.56 Å resolution from a single crystal. Data were reduced using MOSFLM (Battye et al., 2011 ▶) and SCALA (Evans, 2006 ▶) from CCP4 (Winn et al., 2011 ▶)

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

Phases were determined by molecular replacement with Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▶), using the structure of the LRR domain from PP32 (PDB entry 2je0; Huyton & Wolberger, 2007 ▶) as a model. The solution, consisting of two molecules in the asymmetric unit, was first refined as a rigid body and then by restrained refinement using phenix.refine (Afonine et al., 2012 ▶) and manual model building using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▶). We also performed a final refinement cycle with TLS (translation/libration/screw) refinement (Schomaker & Trueblood, 1968 ▶). phenix.validate was used for model validation (Adams et al., 2010 ▶).

Interchain interactions were analyzed with CONTACT/ACT (Kabsch & Sander, 1983 ▶) as implemented in CCP4 (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). Only high-probability electrostatic interactions have been considered for comparison. Model images were generated with Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004 ▶)

3. Results and discussion

The crystals belonged to space group P21 (Table 3 ▶) and contained two molecules in the asymmetric unit, with a solvent content of 42%, which is around 20% lower than those of the two previously reported structures. The higher resolution structure improves the global validation metrics, and the side-chain outliers decrease from 9.1% in the 2.4 Å resolution model to 1.1% in our 1.56 Å resolution structure. The final model included 149 residues of PP32A and three further amino acids at the N-terminus resulting from the cloning and protease-cleavage strategies. The 1.56 Å resolution structure has been refined to a final R work and R free of 0.1706 and 0.2048, respectively (Table 4 ▶). No PP32A residues in the asymmetric unit were found in the Ramachandran disallowed regions. The better resolution of our crystal allowed us to identify different rotamers for residues Leu22, Asn59, Arg75, Lys99, Thr105, Thr126, Tyr144 and Tyr148 compared with the molecules in PDB entries 2je0 and 2je1. A double conformation has also been detected for Arg28.

Table 3. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Diffraction source | ALBA synchrotron |

| Wavelength () | 0.9795 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | Pilatus 6M |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 258.67 |

| Rotation range per image () | 0.1 |

| Total rotation range () | 120 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 0.1 |

| Space group | P1211 |

| a, b, c () | 48.04, 50.88, 63.02 |

| , , () | 90, 110.19, 90 |

| Mosaicity () | 0.865 |

| Resolution range () | 45.091.56 (1.6151.559) |

| Total No. of reflections | 87304 (7888) |

| No. of unique reflections | 36978 (3587) |

| Completeness† (%) | 90.50 (85.63) |

| Multiplicity | 2.3 (2.2) |

| I/(I)‡ | 12.14 (1.77) |

| R meas § | 0.05 |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (2) | 17.07 |

The cystal orientation and morphology did not allow complete data collection.

Themean I/(I) in the outer shell is 2.0 at 1.6 resolution.

R

meas =

, where I

i(hkl) are the observed intensities, I(hkl) is the average intensity and N(hkl) is the multiplicity of reflection hkl.

, where I

i(hkl) are the observed intensities, I(hkl) is the average intensity and N(hkl) is the multiplicity of reflection hkl.

Table 4. Structure refinement.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Resolution range () | 45.091.559 |

| Completeness (%) | 90.50 (85.63) |

| Cutoff | 1.63 |

| No. of reflections, working set | 36969 |

| No. of reflections, test set | 1851 |

| Final R work † | 0.1603 (0.2514) |

| Final R free ‡ | 0.1929 (0.2808) |

| Cruickshank DPI§ | 0.13 |

| No. of non-H atoms | |

| Protein | 2456 |

| Ion | 2 |

| Ligand | 12 |

| Water | 163 |

| Total | 2633 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bonds () | 0.007 |

| Angles () | 1.07 |

| Average B factors (2) | |

| Overall | 28.0 |

| Protein | 25.6 |

| Ion | 27.0 |

| Ligand | 33.2 |

| Water | 30.3 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favoured regions (%) | 97 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 3 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 |

R

work =

, where F

obs and F

calc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

, where F

obs and F

calc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

R free is the same as R work but was calculated using 5% of the total reflections that were selected randomly and excluded during refinement.

Diffraction-component precision indicator (Cruickshank, 1999 ▶).

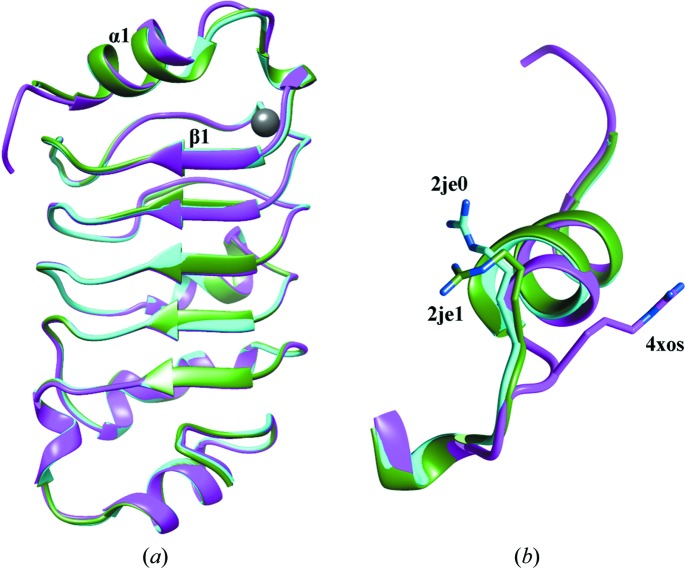

Superimposition of the Cα atoms among monomers from PDB entries 4xos, 2je0 and 2je1 shows a root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of around 0.5 Å, indicating high similarity to the previous structures deposited in the PDB (Huyton & Wolberger, 2007 ▶). The main differences in the Cα trace are located in the turn between helix α1 and strand β1 at the N-terminus (Fig. 1 ▶ a). This difference is maintained in all of the molecules in the asymmetric unit from previous structures. In particular, Arg12 adopts a totally different conformation (Fig. 1 ▶ b) in both molecules in the asymmetric unit, establishing a double salt bridge with Asp73 from a neighbouring molecule. As a consequence, both Leu11 and Asn13 also occupy different positions in our model with respect to the previously reported structures. The C-terminal part of the α1 helix is also displaced. This N-terminal modified region therefore shows a certain degree of conformational flexibility when comparing the different LRR domain structures, and is in agreement with the higher temperature factors observed in the α1–β1 loop. This finding might be functionally relevant since residues Thr15 and Ser17 have been shown to undergo cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation (Dephoure et al., 2008 ▶).

Figure 1.

(a) Superposition of a ribbon representation of PDB entries 4xos (magenta), 2je0 (cyan) and 2je1 (green) showing a shift of the α1–β1 turn and the chloride position in 4xos (grey). (b) Comparison of the Arg12 side-chain distribution in the shifted area of PDB entries 4xos, 2jeo and 2je1 using the same colour scheme.

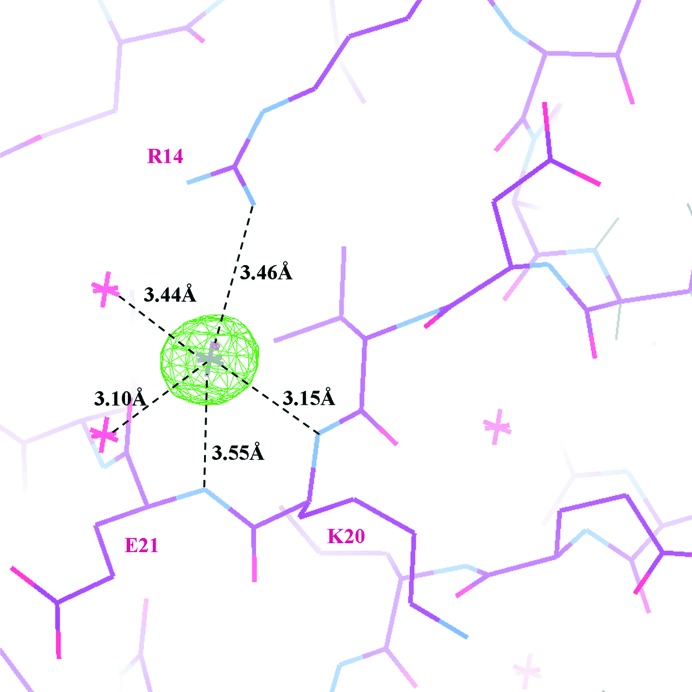

Our structure shows the binding of a chloride ion towards the end of the α1–β1 turn. We assigned the chloride taking into account the ions that were present during purification and crystallization. The chloride interacts with the Nη atom of Arg14, the main-chain N atoms of Lys20 and Glu21 and two water molecules (Fig. 2 ▶). This interacting region immediately precedes the first LRR motif of the protein (Fig. 1 ▶ a) in the vicinity of the largest conformational change between the previously reported structures and our model. The chloride ion site would be occupied by the side chain of Glu21 from neighbouring molecules in the asymmetric units of both PDB entries 2je0 and 2je1, making the presence of this ion incompatible with the previously reported crystallographic space groups.

Figure 2.

Model inside a F o − F c map (green) contoured at the 6σ level. The map was calculated in the absence of chloride and the two interacting water molecules. Interacting distances of the chloride ion (grey) with N atoms belonging to Arg14, Lys20 and Glu21 and with water molecules are shown.

Despite belonging to different space groups, the structures with PDB codes 2je0 and 2je1 reveal related crystal packing (Supplementary Table S1). This degree of conservation is lost when compared with our PP32A structure since most of the contacts are not maintained. The new packing observed is related to the conformational change of the turn connecting the first α-helix to the first β-strand (Supplementary Table S1). PISA analysis (Krissinel & Henrick, 2007 ▶) revealed no change in the protein assembly, which remains as a monomer. This is in agreement with the behaviour of the PP32A LRR domain in size-exclusion chromatography. We can therefore conclude that the differences observed in crystal packing, the new conformation of the α1–β1 turn and the presence of the chloride ion do not have any influence on the oligomerization state of the LRR domain.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: human PP32A LRR domain, 4xos

Supplementtary Table S1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X15006457/hv5292sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

The research received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under BioStruct-X (grant agreement No. 283570). The experiments were performed on the XALOC beamline at the ALBA Synchrotron Light Facility with the collaboration of the ALBA staff. This work was supported by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (SAF2012-31405 and PROMETEO/2012/061 project to JB), Generalitat Valenciana, Spain. SZC received a fellowship from Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad BES2010-030116.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Afonine, P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Echols, N., Headd, J. J., Moriarty, N. W., Mustyakimov, M., Terwilliger, T. C., Urzhumtsev, A., Zwart, P. H. & Adams, P. D. (2012). Acta Cryst. D68, 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. W. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bella, J., Hindle, K. L., McEwan, P. A. & Lovell, S. C. (2008). Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2307–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beresford, P. J., Zhang, D., Oh, D. Y., Fan, Z., Greer, E. L., Russo, M. L., Jaju, M. & Lieberman, J. (2001). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43285–43293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boivin, S., Kozak, S. & Meijers, R. (2013). Protein Expr. Purif. 91, 192–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cruickshank, D. W. J. (1999). Acta Cryst. D55, 583–601. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dephoure, N., Zhou, C., Villén, J., Beausoleil, S. A., Bakalarski, C. E., Elledge, S. J. & Gygi, S. P. (2008). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 10762–10767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huyton, T. & Wolberger, C. (2007). Protein Sci. 16, 1308–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. & Sander, C. (1983). Biopolymers, 22, 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li, M., Makkinje, A. & Damuni, Z. (1996). Biochemistry, 35, 6998–7002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J. (2010). Immunol. Rev. 235, 93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mazroui, R., Di Marco, S., Clair, E., von Roretz, C., Tenenbaum, S. A., Keene, J. D., Saleh, M. & Gallouzi, I.-E. (2008). J. Cell Biol. 180, 113–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muto, S., Senda, M., Akai, Y., Sato, L., Suzuki, T., Nagai, R., Senda, T. & Horikoshi, M. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 4285–4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pan, W., da Graca, L. S., Shao, Y., Yin, Q., Wu, H. & Jiang, X. (2009). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6946–6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E. F., Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Couch, G. S., Greenblatt, D. M., Meng, E. C. & Ferrin, T. E. (2004). J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reinhard, L., Mayerhofer, H., Geerlof, A., Mueller-Dieckmann, J. & Weiss, M. S. (2013). Acta Cryst. F69, 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schomaker, V. & Trueblood, K. N. (1968). Acta Cryst. B24, 63–76.

- Seo, S., Macfarlan, T., McNamara, P., Hong, R., Mukai, Y., Heo, S. & Chakravarti, D. (2002). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14005–14010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: human PP32A LRR domain, 4xos

Supplementtary Table S1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X15006457/hv5292sup1.pdf