Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between the structures of polyphenolic compounds found in grape seed extract (GSE) and their activity in cross-linking dentin collagen in clinically relevant settings.

Methods

Representative monomeric and dimeric GSE constituents including (+)-catechin (pCT), (−)-catechin (CT), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), procyanidin B2 and a pCT-pCT dimer were purchased or synthesized. GSE was separated into low (PALM) and high molecular weight (PAHM) fractions. Human molars were processed into dentin films and beams. After demineralization, 11 groups of films (n=5) were treated for 1 min with the aforementioned reagents (1 wt% in 50/50 ethanol/water) and 1 group remained untreated. The films were studied by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) followed by a quantitative mass spectroscopy-based digestion assay. Tensile properties of demineralized dentin beams were evaluated (n=7) after treatments (2h and 24h) with selective GSE species that were found to protect dentin collagen from collagenase.

Results

Efficacy of GSE constituents in cross-linking dentin collagen was dependent on molecular size and galloylation. Non-galloylated species with degree of polymerization up to two, including pCT, CT, EC, EGC, procyanidin B2 and pCT-pCT dimer were not active. Galloylated species were active starting from monomeric form, including ECG, EGCG, PALM, GSE and PAHM. PALM induced the best overall improvement in tensile properties of dentin collagen.

Significance

Identification under clinically relevant settings of structural features that contribute to GSE constituents’ efficacy in stabilizing demineralized dentin matrix has immediate impact on optimizing GSE’s use in dentin bonding.

Keywords: grape seed extract, proanthocyanidins, dentin collagen, cross-linking, collagenase digestion, tensile properties

1. Introduction

In today’s dental practice, composite restoration faces the lingering problem of longevity particularly for bonding to dentin [1, 2]. One of the leading factors that cause dentin bonding to lose long-term stability is the degradation of demineralized dentin matrix over time [3]. Generated in the bonding procedure by acid etching, this thin layer of denuded collagen fibrils are at elevated risk of hydrolytic and enzymatic breakdown due to water sorption of dental resin and activity of matrix metalloproteinanses (MMPs) [4, 5]. Therefore, collagen cross-linkers and MMP inhibitors have been considered as effective countermeasures to tackle the stability issue of dentin collagen and to eventually improve durability of dentin bonding [6]. In this regard, grape seed extract (GSE), a plant-derived material rich in proanthocyanidins (PAs) has garnered much interest because of the dual functionality as collagen cross-linker and MMP inhibitor [7–14]. Moreover, the efficacy of GSE was verified in clinically relevant settings and in the presence of phosphoric acid, accentuating its great potential as priming agent and etchant additive in bonding applications [15–17].

Nevertheless, the incorporation of GSE in dentin bonding incurs complications for its dark color and polymerization-hindering property [18]. An endeavor to address these problems while preserving GSE’s clinical efficacy would require a precise knowledge of the relationship between GSE components’ structure and their collagen-stabilizing activity. A few recent investigations [19, 20] attempted to probe the biomodification potential of various monomeric and oligomeric species that constitute GSE, but clinical relevance was not of priority in the experimental design.

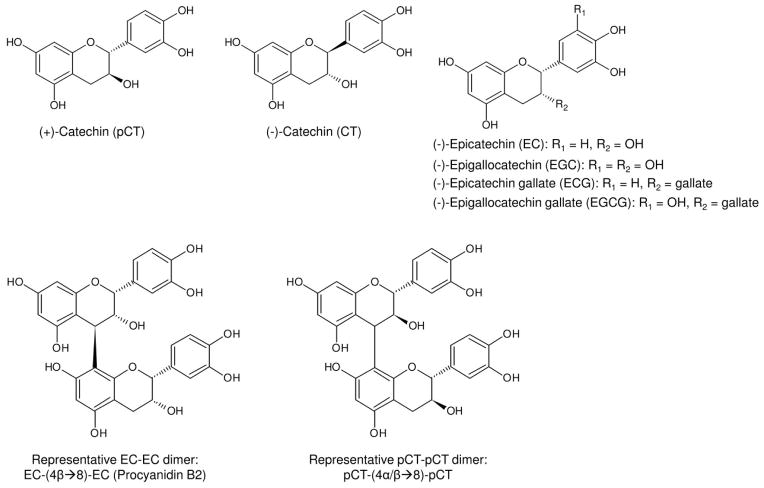

In light of this, we did the present work aiming to emphasize GSE constituents’ collagen-stabilizing activity in clinically relevant settings. The experimental design features ultra-thin (6-μm) dentin films that mimic the acid-etched dentin layer in a total-etch procedure, and short treatment time (1 min) that is clinically feasible. In addition, using thin specimens facilitates the removal of treatment reagent that is physically trapped in the spongy demineralized dentin collagen matrix rather than chemically bound to it. It is believed that the effect of physically-trapped compounds on dentin bonding diminishes over time due to oral fluid exchange, and is therefore of little interest to us as our ultimate goal is to improve long-term bonding to dentin in clinical situations. Overall, six monomeric species, two dimeric species (Fig.1), a low molecular weight fraction (PALM) of commercially available GSE, as well as the original GSE and a high molecular weight fraction (PAHM) were examined representing a gradually increased average molecular size of treatment reagents. The tested null hypothesis is that the structure of the tested chemicals has no effect on their collagen-stabilizing capability.

Fig. 1.

Structure of monomeric and dimeric PA-related species investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), including the 6 monomeric species (+)-catechin (pCT), (−)-catechin (CT), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG) and (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) (Fig. 1). The representative EC-EC dimer, procyanidin B2 was purchased from Chromadex (Irvine, CA, USA). The representative pCT-pCT dimer (Fig. 1) was synthesized from pCT following a published procedure [21]. MegaNatural® Gold grape seed extract (Lot #: 05592502-01) was donated by the manufacturer (Polyphenolics, Madera, CA, USA). All reagents were used as received.

2.2. Preparation and characterization of PALM and PAHM

GSE was separated into a low molecular weight fraction (PALM) and high molecular weight fraction (PAHM) using adapted methods of extraction [22] and preparative size exclusion chromatography (SEC) [23]. In a typical procedure, 2.3 g of grape seed extract was dissolved in 200 mL of deionized water, which was subsequently extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The organic phase was lyophilized to remove the solvent, and approximately 0.27 g of residue was collected as PALM. The water phase was air-dried, re-dissolved in 20 mL of methanol, and loaded on a column (250 × 16 mm internal diameter) packed with Toyopearl TSK HW-40F resin (Tosoh, Japan). The column was sequentially eluted by methanol, water and acetone/water mixtures (20/80, 30/70, 40/60, 60/40, v/v). The resultant fractions were lyophilized and the last fraction (approximately 0.7 g) was designated as PAHM.

PALM, GSE and PAHM were subject to molecular weight analysis using gel permeation chromatography (GPC) following acetylation [22]. Typically, the GSE-derived fraction (20 mg) was dissolved in a mixture of acetic anhydride (10 mL) and pyridine (10 mL, anhydrous) under N2. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 72 h. Ice-cold water (~ 300 mL) was then added to the reaction mixture leading to precipitation of acetylated product. The precipitates were collected by centrifugation and washed a few times with distilled water and methanol. GPC analysis were performed on a Tosoh Ecosec HLC-8320GPC system with three detectors used for measurements including a differential refractometer, a light scattering detector, and a UV detector [24]. The mobile phase was tetrahydrofuran at 0.3 mL/min. Calibration of the system was performed with five different polystyrene standards (8000 to 90000 Da).

2.3. Preparation of treatment and collagenase solutions

The treatment solutions were prepared by dissolving the 11 compounds to be tested, including pCT, CT, EC, EGC, ECG, EGCG, EC-EC dimer, pCT-pCT dimer, PALM, GSE and PAHM in ethanol/water (50/50, v/v) to a final concentration of 1 wt%. All treatment solutions had similar pH between 5 and 6 due to the weak acidity of phenol groups. For the collagenase solution, a TESCA buffer was first prepared by the addition of 11.5 g N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, 50 mg sodium azide and 53 mg CaCl2·2H2O into distilled water to a total volume of 1000 mL, followed by pH adjustment to 7.4. Then 1 g of collagenase with a molecular weight of ~110 kDa (Collagenase Type I, Clostridiopeptidase A from Clostridium histolyticum, 125 U/mg) was dissolved in the TESCA buffer to a final concentration of 0.1% (w/v).

2.4. Preparation, demineralization and cross-linking of dentin films

Six non-carious human molars were collected after obtaining the patients’ informed consent under a protocol approved by the University of Missouri-Kansas City Adult Health Sciences IRB (IBC#12-14). Extracted teeth were stored at 4°C in 0.96% (w/v) phosphate buffered saline containing 0.002% sodium azide. A water-cooled low-speed diamond saw (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) was used to remove the occlusal one-third to one-half of the crown, followed by four additional cuts in the occlusal-apical direction to remove all side walls of the enamel. The resultant dentin block was sectioned in the mesial-distal direction, with a tungsten carbide knife mounted on an SM2500S microtome (Leica, Deerfield, IL, USA), into dentin films 6 μm thick. A total of 300 films (50 from each tooth) were obtained, and the final size of each film was uniform and approximately 5 mm × 5 mm.

Sixty dentin films were randomly assigned to 12 groups (n = 5), including 11 treated groups and 1 control group. Each dentin film was demineralized with 35 wt% phosphoric acid for 15 s, rinsed in deionized water for 10 s, and then spread on a plastic cover slip (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) with the aid of a fine paintbrush. After blotting away the excessive water, a small drop (approx. 0.15 ml) of selected treatment solution or deionized water (the control group) was immediately applied to cover the entire demineralized dentin film. After 1 min, the film was flushed with deionized water three times and further immersed in a copious amount of deionized water for 1 h to thoroughly remove any residual treatment solution. After being air dried overnight, the films were subject to the FTIR and collagenase digestion analyses.

2.5. FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra of control and treated demineralized dentin films were collected at a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 128 scans per sample using a Fourier transformed infrared spectrometer equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) attachment (Spectrum One, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The ATR crystal was diamond with a transmission range between 650 and 4000 cm−1, and a gauge force of 75 was applied to ensure a good contact between the films and the ATR top-plate. Area determination was performed for bands at 1235 cm−1 (amide III) and 1450 cm−1 (CH2 scissoring) using Spectrum software (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) following a two-point baseline correction and band area integration, and the band ratio (A1235/A1450) was calculated.

2.6. Resistance toward bacterial collagenase digestion

Following FTIR spectroscopy, the dentin collagen films were individually incubated in 30 μl of collagenase at 37 °C for 1 h, after which the remaining films were removed and the digest liquids were incubated for additional 24 h to ensure complete breakdown of solubilized collagen to tripeptides. The percentage of dentin film that was digested and released into the supernatants was gauged by MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy following a published protocol [15], which is based on the signal strength of glycine-proline-arginine, a tripeptide resulted from the digestion of collagen by bacterial collagenase.

2.7. Preparation, demineralization and cross-linking of dentin beams

Like dentin films, dentin beams were obtained from non-carious human molars collected with patients’ consent. After removing the occlusal one-third to one-half of the crown, the same saw was used to make perpendicular cuts into the dentin surface at ~1.1 mm increments. A single cut was then made parallel to and about 1.1 mm beneath the surface dentin, which freed the dentin beams from the remaining dentin block. The final cross-section of the beams was approximately 0.8 × 0.8 mm, and the length varied with respect to their position. All beams were carefully checked under light microscopy to make sure there was no remaining enamel or any defect. Eventually, a total of 11 teeth were processed into 63 dentin beams, which were pooled together and subject to complete demineralization in 10% phosphoric acid for 6 h [8]. The resultant demineralized dentin beams were randomly assigned to 9 groups (n = 7), including 1 control group and 8 treated groups. Beams in the treated groups were immersed in selected solutions that were found to increase dentin films’ resistance to biodegradation (see Results below), including EGCG, PALM, GSE and PAHM for 2 h or 24 h. After treatment, the beams were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water and continued to be immersed in a large amount of deionized water for 24 h to remove residual treatment solution. The beams were stored in deionized water at 4 °C until tensile testing.

2.8. Tensile tests of dentin beams

The tensile properties of the beams were determined using an SSTM-5000 tensile tester (United Calibration Corporation, CA, USA) at a fixed gauge length of 2 mm. Specimens were mounted to the upper and lower grips of the tensile tester using a cyanoacrylate adhesive (Zapit, Dental Ventures of America, Corona, CA, USA). A constant strain rate of 0.5 mm/min was applied to stretch the dentin beams till failure. The direction of load was perpendicular to dentinal tubules owing to the manner of beam harvesting. During the test, specimens were kept fully hydrated with a water mist sprayer. Three tensile properties were retrieved from the stress-strain curves. First, the slope of the initial linear portion (up to strain of 1.5 – 5% depending upon treatment conditions) was calculated, representing the “initial modulus” (Ei). Second, the elastic modulus (E) was determined as the slope of the later linear portion, usually extending all to way to where failure occurred. Third, the maximum stress at the point of failure (correspondingly the peak value of the stress-strain curve) was recorded as the ultimate tensile strength (UTS).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses for FTIR band ratio and collagenase digestion were performed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. For tensile properties, the interaction between treatment agent and treatment time was analyzed by two-way ANOVA. The comparison of means across treatment agents was carried out by split file one-way ANOVA and either Tukey’s post hoc test (equal variance) or Dunnett’s T3 post hoc test (unequal variance). The comparison of means across treatment times was done by t-test. All statistical analyses were performed at 95% confidence level (differences were considered significant if p < 0.05).

3. Results

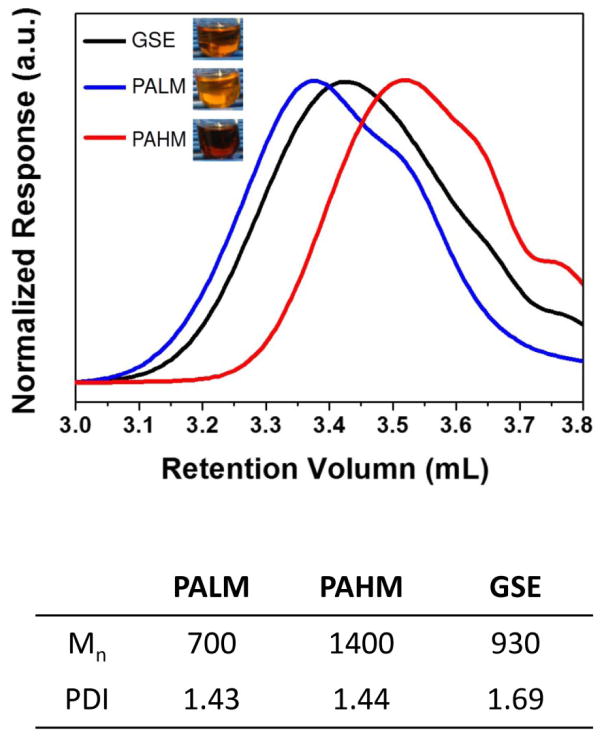

3.1. GPC of PALM, GSE and PAHM

The retention times of PALM, GSE and PAHM in GPC can be seen in Fig. 2. The number-average molecular weight (Mn) of PALM, GSE and PAHM were approximately 700, 930 and 1400, respectively. PALM and PAHM had narrower distribution of molecular weight as evidenced by lower polydispersity index (PDI) compared to original GSE.

Fig. 2.

GPC characterization of PALM, PAHM and GSE. Next to legends: physical appearance in solution (1% in 50/50 ethanol/water).

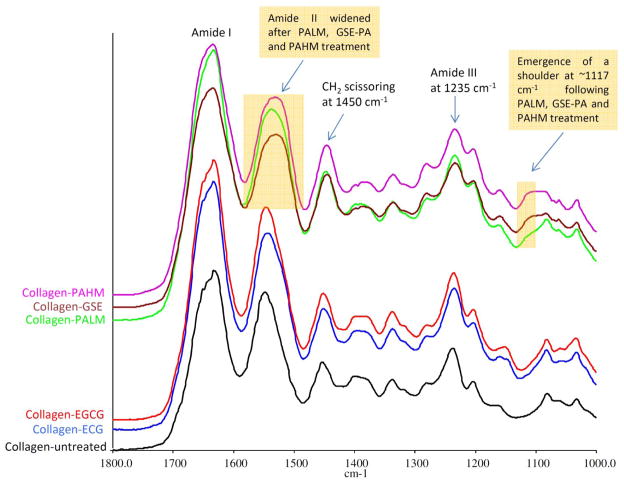

3.2. FTIR spectroscopy

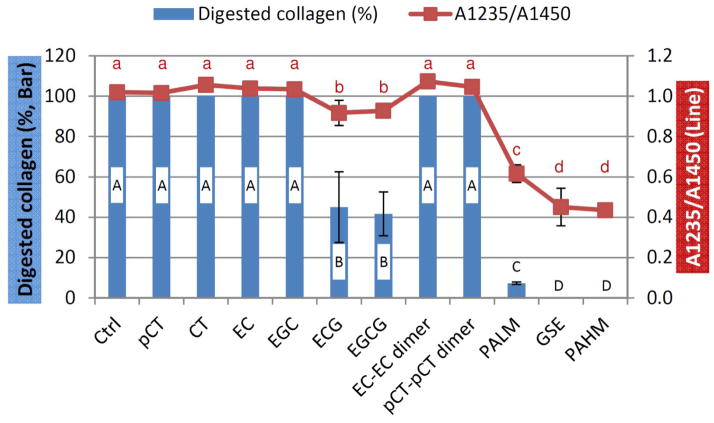

Representative FTIR spectra of demineralized dentin films with and without treatment were shown in Fig. 3. The major bands of type I collagen including amide I at ~1633 cm−1, amide II at ~1544 cm−1, CH2 bending at ~1450 cm−1, and amide III at ~1235 cm−1 were evident in all spectra. Compared to untreated control, demineralized dentin collagen after pCT, CT, EC. EGC, EC-EC dimer and pCT-pCT dimer treatments resulted in no change in terms of band shape or location, and those spectra were therefore not shown. Treatments with ECG and EGCG led to subtle changes to dentin collagen’s spectra which were more evident in the following band ratio analysis. PALM, GSE and PAHM treatments caused the most obvious alterations, including widened amide II, emergence of shoulder at ~1117 cm−1 and shrunken amide III which could be attributed to spectral traces of treatment reagents [17]. Quantitatively, the amide III/CH2 band ratio (A1235/A1450) of specimens treated by ECG and EGCG was slightly but significantly lower than control, followed by PALM-treated, and then GSE and PAHM-treated specimens (Fig. 4, line).

Fig. 3.

FTIR spectra of dentin collagen films with no treatment (black) and after 1 min of treatment with ECG (blue), EGCG (red), PALM (green), GSE (brown) and PAHM (purple).

Fig. 4.

The A1235/A1450 band ratio of untreated and treated dentin collagen films (red line) and their corresponding degree of digestion after 1 h of collagenase challenge (blue bar). Values with the same lower case letters are statistically equivalent (n =5).

3.3. Resistance to bacterial collagenase digestion

Untreated dentin collagen films underwent complete digestion (Fig. 4, bar) after 1 h of incubation in 0.1% collagenase at 37°C. The non-galloylated monomeric species including pCT, CT, EC and EGC failed to enhance dentin collagen’s enzymatic stability, as dentin collagen films treated by them were completely digested as well. The two galloylated monomeric compounds ECG and EGCG significantly increased dentin collagen’s resistance to collagenase, in which case the degree of digestion decreased to 45.0 ± 17.5% and 41.7 ± 10.9%, respectively. Surprisingly, the representative dimers EC-EC and pCT-pCT did not have any effect on dentin collagen’s enzymatic stability. In comparison, films treated by PALM lost 7.2 ± 0.6% of collagen, whereas those treated by GSE and PAHM were protected entirely.

3.4. Tensile testing

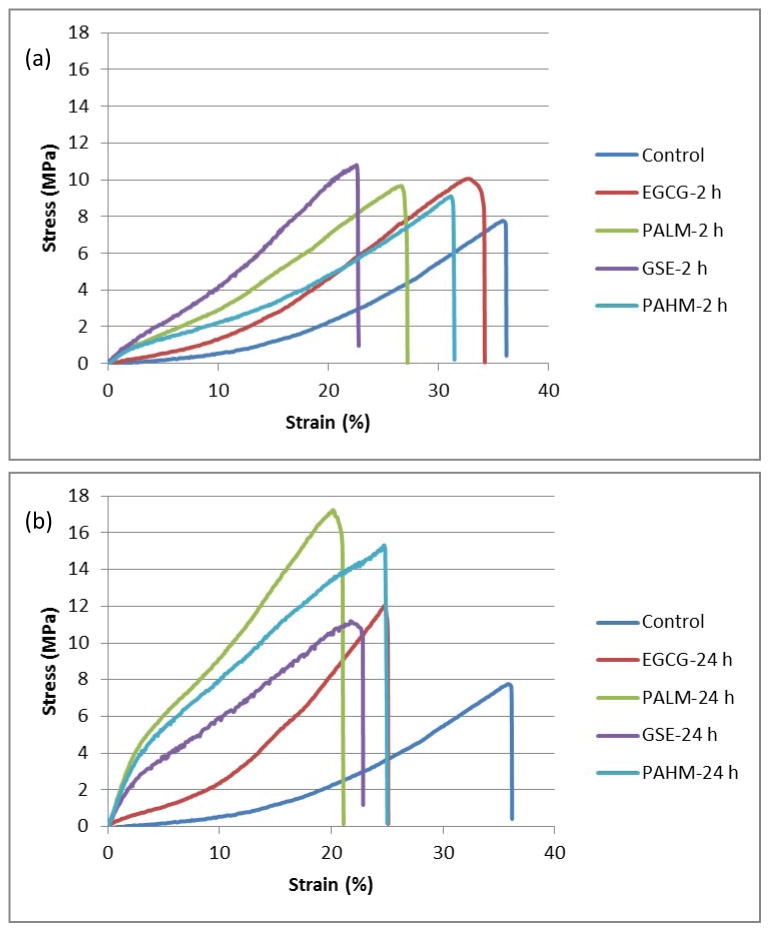

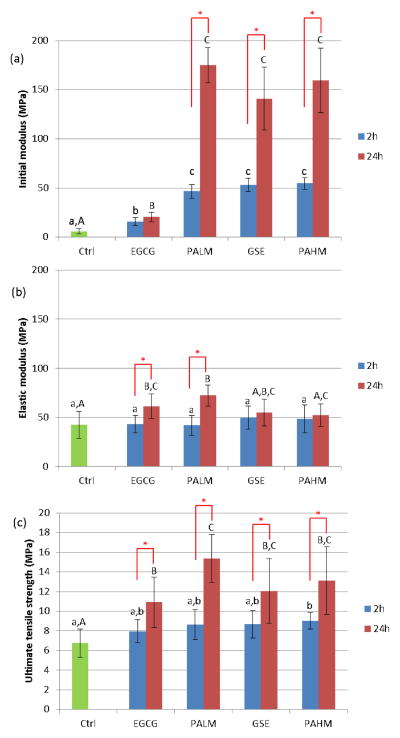

Representative stress-strain curves of demineralized dentin beams before, after 2 h and after 24 h of treatment were shown in Fig. 5. Note the obvious shape change after 24 h of treatment with PALM, GSE and PAHM, in which case the initial slope Ei surpassed the elastic slope E. Two-way ANOVA revealed that the factors of treatment agent and time were independent of each other. Increasing treatment time from 2 h to 24 h led to significant improvement in all tensile properties except Ei for EGCG (p = 0.07), E for GSE (p = 0.45) and E for PAHM (p = 0.76). On the other hand, treatment reagent exhibited rather distinctive effect on Ei, E and UTS, respectively. Ei was sensitive to all treatment reagents (Fig. 6a), following a trend of Ctrl < EGCG < PALM = GSE = PAHM regardless of treatment time. E was not sensitive to any treatment reagent at 2 h (Fig. 6b) as all groups had equivalent E values. At prolonged treatment (24 h), significantly higher E was seen for EGCG and PALM-treated specimens. UTS was not sensitive to treatment reagent at 2 h, either, with only PAHM leading to significantly higher UTS. Prolonged treatment (24 h) resulted in significantly enhanced UTS for all reagents tested.

Fig. 5.

Representative stress-strain curves of dentin collagen beams treated with EGCG, PALM, GSE-PAGSE and PAHM for (a) 2 h; and (b) 24 h. The curves of untreated control exhibited typical characteristics of a collagenous soft tissue, featuring a toe region with low and slow-rising slope followed by a linear elastic region with high and constant slope. Obvious shape change can be seen after PALM, GSE and PAHM treatment for 24 h.

Fig. 6.

Tensile properties of dentin collagen beams following 2 h and 24 h of treatment, including (a) initial modulus; (b) elastic modulus; and (c) ultimate tensile strength. Star (*): significant difference between 2 h and 24 h of treatment. Same lower case letters: statistically equivalent after 2 h of treatment. Same upper case letters: statistically equivalent after 24 h of treatment (n = 7).

4. Discussion

It is common practice to process dentin into beams or slabs with dimensions in the millimeter range when investigating the biomodification of dentin collagen [7–11, 13, 19, 20]. However, doing so diminishes the significance of discovery from the perspective of practicality. Long treatment time becomes inevitable to allow diffusion of treatment solutions into the specimen, which not only impacts the clinical relevance of research but also raises uncertainties related to the self-polymerization of polyphenolic compound via auto-oxidation [25, 26]. Pertaining to the latter concern, all solutions in the present study were freshly prepared and used right away.

Following treatment by ECG, EGCG, PALM, GSE and PAHM for 1 min, demineralized dentin collagen’s FTIR spectra were altered (Fig. 3) and consequently presented lower A1235/A1450 band ratio than untreated control (Fig. 4). Similar lower A1235/A1450 band ratio was previously reported in PA-crosslinked dentin collagen presumably due to PA’s minute contribution to the former band but substantial contribution to the latter [15]. These spectral changes are solid proof that dentin collagen is capable of interacting with and immobilizing the aforementioned compounds in clinically relevant time. Conversely, treatment with non-galloylated monomeric and dimeric species (pCT, CT, EC, EGC, EC-EC dimer and pCT-pCT dimer) resulted in unaltered FTIR spectra with A1235/A1450 ratios equivalent to the control, indicating they could not bind to dentin collagen and were subsequently rinsed off from the ultra-thin specimens.

Depending upon the identity of treatment solutions, demineralized dentin films showed various degrees of digestion when challenged by bacterial collagenase (Fig. 4). Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected. With regard to structure-activity relationship, many earlier studies demonstrated that the interaction between polyphenolic compounds and proteins was dependent on the ligand’s size – larger polyphenolics generally bind to proteins more effectively [27–30]. Our results suggest that molecular size is not the only factor when it comes to GSE constituents interacting with dentin collagen, as the two representative dimers (EC-EC and pCT-pCT) surprisingly do not have any effect although they have higher molecular weight (578.5) than ECG (442.4) and EGCG (458.4). It accentuates the importance of O-3-galloylation in PA species’ bioactivity, as observed in previous studies regarding biomodification of dentin matrix [19, 20] as well as other aspects of their biological functions [31–34]. Interestingly, the treated specimens’ digestion behavior matched very well with their A1235/A1450 ratios obtained from the FTIR measurements (Fig. 4). Untreated control had A1235/A1450 value of 1 and no resistance to degradation. Treated specimens with A1235/A1450 ratio equivalent to control exhibited no resistance either, whereas those with lower A1235/A1450 ratio showed resistance, and the lower the ratio was, the less digested the treated dentin collagen was. Thus, FTIR could be a fast and convenient way to screen effective PA species from ineffective ones.

With regard to tensile properties, long treatment times (2 h and 24 h) were used due to larger specimen size. EGCG, PALM, GSE and PAHM all had positive influence, but their individual effect on Ei, E and UTS was rather complicated (Fig. 6). The Ei values, derived from the toe area of collagen’s stress-strain curves, are generally accepted to correspond to the “de-crimping” event that straightens the gap zone of collagen fibrils. On the other hand, the E values, calculated from the linear elastic area, are related to the sliding action of collagen molecules within straightened fibrils [35, 36]. Accordingly, Ei and E values should reflect the degree of modification in the gap zone and overlap zone, respectively. From 2 h to 24 h, Ei of EGCG-treated specimens increased by 1.3 fold, in line with the increase of E (1.4 fold). In contrast, Ei of PALM, GSE and PAHM treated specimens increased by 3.7, 2.6 and 2.9 fold, respectively, more than double the change of E (1.7, 1.1 and 1.1 fold, respectively). The drastically elevated Ei, which even surpassed E after 24 h of treatment (hence the shape change of stress-strain curves of PALM, GSE and PAHM in Fig. 5) suggests that the active PA oligomers probably interact with the gap zone of collagen fibrils more readily than with the overlap zone, consistent with a long-speculated proposition [37]. Notably, PALM was the only reagent that augmented both Ei and E significantly in 24 h (Fig. 6a and 6b), and as a result, the PALM-treated samples had the highest UTS (Fig. 6c) that stood out from the other GSE-related reagents to be significantly higher than their EGCG-treated counterparts.

In summary, the efficacy of PA monomer and oligomers in stabilizing dentin collagen is dependent on molecular size and galloylation. Within the limitation of the study, and in the context of clinically relevant treatment, non-galloylated species with degree of polymerization equal to or below two are not active, whereas galloylated species are active in the monomer form although their activity is not as high as GSE-derived PA oligomers such as PALM. Refined from original GSE using ethyl acetate extraction, PALM affords near-full protection and best overall mechanical fortification of demineralized dentin matrix while presenting a lower molecular weight and less intense color compared to GSE.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by USPHS Research Grants R15-DE021023 and R01-DE021431-01A1 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.De Munck J, Van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Poitevin A, Lambrechts P, Braem M, et al. A critical review of the durability of adhesion to tooth tissue: Methods and results. J Dent Res. 2005;84:118–32. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loguercio AD, Moura SK, Pellizzaro A, Dal-Bianco K, Patzlaff RT, Grande RHM, et al. Durability of enamel bonding using two-step self-etch systems on ground and unground enamel. Oper Dent. 2008;33:79–88. doi: 10.2341/07-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabatini C, Pashley DH. Mechanisms regulating the degradation of dentin matrices by endogenous dentin proteases and their role in dental adhesion. A review Am J Dent. 2014;27:203–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tjäderhane L, Nascimento FD, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Tersariol ILS, Geraldeli S, et al. Strategies to prevent hydrolytic degradation of the hybrid layer - A review. Dent Mater. 2013;29:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perdigão J, Reis A, Loguercio AD. Dentin adhesion and MMPs: A comprehensive review. J Esthetic Restorative Dent. 2013;25:219–41. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Tjäderhane L, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Li N, Mao J, et al. Limitations in bonding to dentin and experimental strategies to prevent bond degradation. J Dent Res. 2011;90:953–68. doi: 10.1177/0022034510391799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedran-Russo AKB, Pereira PNR, Duarte WR, Drummond JL, Yamaychi M. Application of crosslinkers to dentin collagen enhances the ultimate tensile strength. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;80:268–72. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellan CS, Pereira PN, Grande RHM, Bedran-Russo AK. Mechanical characterization of proanthocyanidin-dentin matrix interaction. Dent Mater. 2010;26:968–73. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green B, Yao X, Ganguly A, Xu C, Dusevich V, Walker MP, et al. Grape seed proanthocyanidins increase collagen biodegradation resistance in the dentin/adhesive interface when included in an adhesive. J Dent. 2010;38:908–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Chen M, Yao X, Xu C, Zhang Y, Wang Y. Enhancement in dentin collagen’s biological stability after proanthocyanidins treatment in clinically relevant time periods. Dent Mater. 2013;29:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epasinghe DJ, Yiu CKY, Burrow MF, Hiraishi N, Tay FR. The inhibitory effect of proanthocyanidin on soluble and collagen-bound proteases. J Dent. 2013;41:832–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaussain C, Boukpessi T, Khaddam M, Tjaderhane L, George A, Menashi S. Dentin matrix degradation by host matrix metalloproteinases: Inhibition and clinical perspectives toward regeneration. Front Physiol. 2013;4:Article 308. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheffel DLS, Hebling J, Scheffel RH, Agee K, Turco G, De Souza Costa CA, et al. Inactivation of matrix-bound Matrix metalloproteinases by cross-linking agents in acid-etched dentin. Oper Dent. 2014;39:152–8. doi: 10.2341/12-425-L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedran-Russo AK, Pauli GF, Chen SN, McAlpine J, Castellan CS, Phansalkar RS, et al. Dentin biomodification: Strategies, renewable resources and clinical applications. Dent Mater. 2014;30:62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Wang Y. Proanthocyanidins’ efficacy in stabilizing dentin collagen against enzymatic degradation: MALDI-TOF and FTIR analyses. J Dent. 2013;41:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Dusevich V, Wang Y. Proanthocyanidins rapidly stabilize the demineralized dentin layer. J Dent Res. 2013;92:746–52. doi: 10.1177/0022034513492769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Dusevich V, Wang Y. Addition of grape seed extract renders phosphoric acid a collagen-stabilizing etchant. J Dent Res. 2014;93:821–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034514538972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Wang Y. Effect of proanthocyanidins and photo-initiators on photo-polymerization of a dental adhesive. J Dent. 2013;41:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vidal CMP, Leme AA, Aguiar TR, Phansalkar R, Nam JW, Bisson J, et al. Mimicking the hierarchical functions of dentin collagen cross-links with plant derived phenols and phenolic acids. Langmuir. 2014;30:14887–93. doi: 10.1021/la5034383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vidal CMP, Aguiar TR, Phansalkar R, McAlpine JB, Napolitano JG, Chen SN, et al. Galloyl moieties enhance the dentin biomodification potential of plant-derived catechins. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:3288–94. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozikowski AP, Tückmantel W, Böttcher G, Romanczyk LJ., Jr Studies in polyphenol chemistry and bioactivity. 4. Synthesis of trimeric, tetrameric, pentameric, and higher oligomeric epicatechin-derived procyanidins having all-4β,8-interflavan connectivity and their inhibition of cancer cell growth through cell cycle arrest. J Org Chem. 2003;68:1641–58. doi: 10.1021/jo020393f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saucier C, Mirabel M, Daviaud F, Longieras A, Glories Y. Rapid fractionation of grape seed proanthocyanidins. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5732–5. doi: 10.1021/jf010784f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu SF, Zou B, Yang J, Yao P, Li CM. Characterization of a highly polymeric proanthocyanidin fraction from persimmon pulp with strong Chinese cobra PLA 2 inhibition effects. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S, Li Y, Wisner CA, Jin L, Leventis N, Peng Z. Synthesis, optical properties and photovoltaic applications of hybrid rod-coil diblock copolymers with coordinatively attached CdSe nanocrystals. RSC Adv. 2014;4:35823–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mochizuki M, Yamazaki SI, Kano K, Ikeda T. Kinetic analysis and mechanistic aspects of autoxidation of catechins. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2002;1569:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poncet-Legrand C, Cabane B, Bautista-Ortín AB, Carrillo S, Fulcrand H, Pérez J, et al. Tannin oxidation: Intra-versus intermolecular reactions. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:2376–86. doi: 10.1021/bm100515e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon C, Barathieu K, Laguerre M, Schmitter JM, Fouquet E, Pianet I, et al. Three-dimensional structure and dynamics of wine tannin-saliva protein complexes A multitechnique approach. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10385–95. doi: 10.1021/bi034354p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frazier RA, Deaville ER, Green RJ, Stringano E, Willoughby I, Plant J, et al. Interactions of tea tannins and condensed tannins with proteins. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2010;51:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brás NF, Gonçalves R, Mateus N, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ, De Freitas V. Inhibition of pancreatic elastase by polyphenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:10668–76. doi: 10.1021/jf1017934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cala O, Dufourc EJ, Fouquet E, Manigand C, Laguerre M, Pianet I. The colloidal state of tannins impacts the nature of their interaction with proteins: The case of salivary proline-rich protein/procyanidins binding. Langmuir. 2012;28:17410–8. doi: 10.1021/la303964m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veluri R, Singh RP, Liu Z, Thompson JA, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Fractionation of grape seed extract and identification of gallic acid as one of the major active constituents causing growth inhibition and apoptotic death of DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1445–53. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal C, Veluri R, Kaur M, Chou SC, Thompson JA, Agarwal R. Fractionation of high molecular weight tannins in grape seed extract and identification of procyanidin B2-3,3′-di-O-gallate as a major active constituent causing growth inhibition and apoptotic death of DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1478–84. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou SC, Kaur M, Thompson JA, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Influence of gallate esterification on the activity of procyanidin B2 in androgen-dependent human prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells. Pharm Res. 2010;27:619–27. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-0037-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makimura M, Hirasawa M, Kobayashi K, Indo J, Sakanaka S, Taguchi T, et al. Inhibitory effect of tea catechins on collagenase activity. J Periodontol. 1993;64:630–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.7.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puxkandl R, Zizak I, Paris O, Keckes J, Tesch W, Bernstorff S, et al. Viscoelastic properties of collagen: Synchrotron radiation investigations and structural model. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2002;357:191–7. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maganaris CN, Narici MV, Almekinders LC, Maffulli N. Biomechanics of the Achilles Tendon. In: Nunley JA, editor. The Achilles Tendon: Treatment and Rehabilitation. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haslam E. Natural polyphenols (vegetable tannins) as drugs: Possible modes of action. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:205–15. doi: 10.1021/np960040+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]