Background

Efavirenz (EFV) is used as part of a highly active anti-retroviral therapy (ART) regimen (HAART) against HIV-1 infection [1, 2]. It is important to achieve correct dosage of anti-viral medications: too high a concentration of plasma EFV may increase risk for toxicity, including neurologic toxicity (such as sleep disorders and hallucinations) [3-6], whereas too low a concentration may be associated with virologic failure [7, 8]. A therapeutic EFV range of 1-4 μg/mL is suggested, although patients with EFV plasma concentrations of >4 μg/mL do not experience substantially greater side effects than those with lower concentrations, and it is unclear whether concentrations of <1 μg/mL are associated with increased virologic failure in patients adhering to EFV treatment [9, 10]. Enzymes involved in the breakdown of EFV have an important role in this balance. Drugs taken concomitantly by HIV patients can affect EFV levels by inhibiting or inducing these enzymes, and EFV itself induces its own metabolism by increasing the expression of or activating some of these enzymes. Polymorphisms in the genes that encode these enzymes may also affect EFV concentrations, helping to explain some of the high variability in EFV plasma concentrations observed between individuals when given the same recommended daily dose [8, 11-13]. In this summary we focus on the latter interaction: the pharmacogenetics of EFV. An interactive version of this summary can be viewed at https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166123135.

Pharmacodynamics

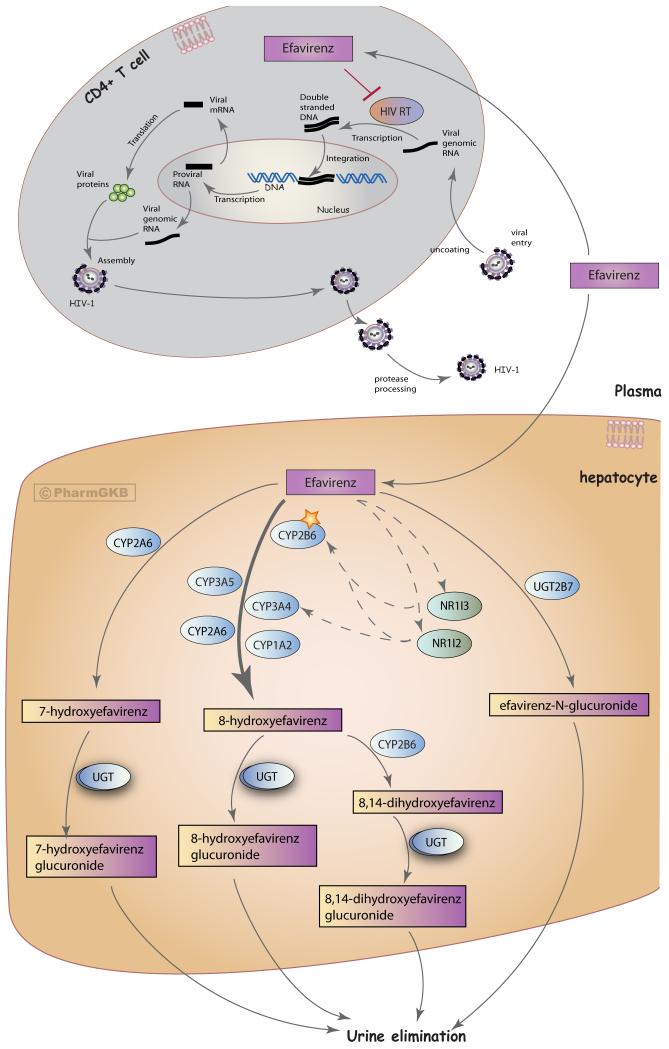

An array of antiretroviral drugs are now available that target different stages of the HIV-1 life-cycle (for a comprehensive review see [2]). EFV is amongst the molecules that target HIV-1 reverse transcriptase, preventing the formation of viral double-stranded DNA from the single-stranded viral RNA genome (Figure 1) [2]. These drugs can be divided into two classes: analogs of nucleoside substrates (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: NRTIs) and non-NRTIs (NNRTIs) that bind to a non-catalytic site of the reverse transcriptase enzyme; EFV is in the latter class [2]. Mutations in the gene encoding the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase enzyme are associated with resistance to NRTIs and NNRTIs, including EFV [14]; however, in this summary we focus on variants in the human genome and their effect on EFV pharmacokinetics and treatment.

Figure 1.

Stylized cells depicting the metabolism and mechanism of action of efavirenz. A fully interactive version is available at PharmGKB http://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166123135.

Pharmacokinetics

The major route of EFV metabolism is to 8-hydroxyefavirenz (8-hydroxy-EFV), formed predominately by CYP2B6 (Figure 1) [15-17]. Studies within human liver microsomes have shown that the formation rate of 8-hydroxy-EFV displays considerable variability in different samples [17]. CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP1A2 and CYP2A6 may play minor contributing roles in this xenometabolic step [15-17]. CYP2B6 is also the major enzyme involved in formation of the secondary metabolite 8,14-dihydroxy-EFV [15, 16]. Furthermore, EFV can be hydroxylated to 7-hydroxy-EFV by CYP2A6, a minor pathway of EFV metabolism accounting for around 23% of overall EFV metabolism in vitro [16, 17]. Hence, there are three hydroxylated EFV metabolites: 8-hydroxy-EFV, 8,14-dihydroxy-EFV and 7-hydroxy-EFV.

The predominant mode of EFV excretion is as glucuronides in the urine, with 8-hydroxy-EFV-glucuronide as the major metabolite found [18]. Multiple UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) isoforms (including UGT1A1, 1A3, 1A7, 1A8, 1A9, 1A10, and 2B7) can act upon the three hydroxylated EFV metabolites to produce glucuronide forms [18-20]. In vitro studies have shown that EFV can be directly glucuronidated to EFV-N-glucuronide by UGT2B7 (though this is a minor pathway after the first dose of EFV) [18-22]. The formation rate of EFV-N-glucuronide shows large variability between human microsome samples, whereas formation of 7-hydroxy-EFV-G, 8-hydroxy-EFV-G and 8,14-hydroxy-EFV-G do not [23].

EFV-enzyme interactions and drug-drug interactions

The transcription factors pregnane X receptor (PXR, NR1I2) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR, NR1I3) are activated to different extents by different drugs. Their target genes include those involved in xenobiotic metabolism and elimination, and therefore may underlie drug-drug interactions [9, 24, 25]. EFV is thought to enhance its own metabolism (autoinduction) by inducing the expression of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 via activation of NR1I3 and NR1I2 [24, 26-28]. Other drugs can also induce CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 expression, including rifampin (an anti-tuberculosis drug often taken concomitantly with EFV in patients with HIV and tuberculosis co-infection) via the activation of NR1I2 [24, 25, 28]. In vitro, EFV has been seen to competitively inhibit bupropion 4-hydroxylation by CYP2B6, as well as inhibiting CYP2C8, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 activity [29, 30].

Pharmacogenetic studies have provided insight into the variability seen in EFV PK between patients [31].The effect EFV has on metabolizing enzymes, and the drug-drug interactions between EFV and other antiretrovirals or medications commonly taken concomitantly by HIV patients, may influence the safety, adherence, and efficacy of treatment; however, these effects vary between patients and thus are difficult to predict [31]. For example, when comparing samples on day 1 and day 14 in patients treated with EFV-based HAART, some patients exhibit an increase in EFV oral clearance (autoinduction) whilst others do not, and between those that do, the extent of the increase in oral clearance is variable [32]. Importantly, the time-points of samples collected and compared could influence the extent of autoinduction observed [33]. EFV autoinduction is also influenced by a patient’s genotype; for example, patients with the CYP2B6*1 allele may exhibit long-term EFV autoinduction [33, 34]. In selected situations, therapeutic drug monitoring of antiretroviral therapy may help to address these issue by individualizing dosage to minimize side effects while maintaining antiviral efficacy [31, 35], although it is important to note that EFV is often co-formulated in a fixed dose as part of an anti-viral regimen, adding a layer of complexity to individualization of dosage.

Pharmacogenetics

Variants within genes of enzymes involved in the EFV PK pathway have been investigated for association with PK parameters, clinical outcomes and side effects, such as neurologic (CNS) toxicity, one of the most commonly reported adverse events in patients taking EFV.

CYP2B6 variants

As CYP2B6 is the main enzyme involved in EFV metabolism, polymorphisms in the CYP2B6 gene have been extensively investigated for associations with EFV PK parameters, toxicity, and treatment responses. These are summarized in Table 1, with two of the variants described in more detail below.

Table 1.

Summary of EFV PGx associations for variants in the CYP2B6 gene

| Variant common name |

Variant mapping information | Association with EFV in HIV-infected patients |

Association type |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) 516G>T | rs3745274 NM_000767.4:c.516G>T, NP_000758.1:p.Gln172His |

The TT genotype is associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations, reduced clearance and increased drug exposure or plasma exposure compared to the GG and/or GT genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 19659438, 18281305, 15622315, 2308025, 20625352, 20723261, 19779319, 24080498, 20860463, 19371316, 19779319, 24551111, 24316028, 23399569, 23172109, 23970651, 16267764, 18839779, 22927450, 24145522, 15864119, 23254426, 20441246, 15825040, 17356468, 22057858, 24956253, 20338069, 22950382, 22481606, 19704172, 18728241, 19124658, 20952418]. |

| The TT genotype is associated with prolonged EFV plasma concentrations (up to 14 days) after discontinuation of therapy, as compared to GG (around 6 days) and GT (7 days) genotypes. |

PK | [PMID: 16392089] |

||

| The GT genotype is associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations or plasma exposure compared to the GG genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 24551111, 15622315, 24316028, 23399569, 23172109, 19371316, 23970651, 23254426, 15825040] |

||

| Genotypes of the SNP are not associated with EFV plasma concentrations at 2 weeks of treatment. |

PK |

[PMID: 20723261] |

||

| The GT and TT genotypes are associated with increased PBMC- associated EFV concentration/exposure compared to the GG genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 20860463, 15864119] |

||

| Patients with the GG genotype may require a higher dose adjustment. |

PK | [PMID: 18839779] |

||

| The TT genotype or T allele is associated with sleep disorders and fatigue when treated with an EFV- containing regimen. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 15864119, 23734829, 24956253] |

||

| The GT genotype is associated with increased likelihood of worse sleep quality as compared to the GG genotype at 6 months of EFV treatment, but not at 4 or 12 months (sleep quality was not associated with EFV plasma levels in this study). |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23970651] |

||

| Genotypes TT and GT are associated with a higher change in median symptom score for central nervous system side effects (CNS) at week 1 from baseline compared to genotype GG, but no difference between genotypes was seen at week 24. |

Toxicity |

[PMID: 15622315] |

||

| Genotype TT and male gender were associated with an increased risk of CNS side-effects when treated with an EFV-containing regimen. |

Toxicity |

[PMID: 24517233] |

||

| Patients with the TT genotype experienced a higher number of overall side effects compared to those with the GG genotype, but this was not statistically significant. |

Toxicity |

[PMID: 20723261] |

||

| The TT genotype is associated with EFV treatment discontinuation within 3 months of treatment. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 21715435] |

||

| Genotypes of the SNP are not associated with toxicity-related treatment failure when treated with an EFV- containing regimen. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 16267764] |

||

| Genotypes GT and TT are not associated with increased risk of CNS toxicity. |

Toxicity |

[PMID: 24080498] |

||

| Genotypes of the SNP are not associated with switching to a completely new treatment regimen when treated initially with an EFV- containing regimen or with EFV treatment termination. |

Toxicity/ efficacy |

[PMID: 16267764, 15622315] |

||

| Genotypes of the SNP are not significantly associated with virologic failure, plasma HIV-1 RNA copy number, viral loads at 3 or 6 months of treatment, or CD4+ T cell count when treated with an EFV- containing regimen. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 16267764, 15622315, 20723261, 20338069] |

||

| Factors that were associated with increased risk of immunological failure in Ghanaian patients treated with EFV were; genotype GG (compared to genotype TT), less than 95% adherence to treatment, and low baseline CD4+ T cell counts. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 24080498] |

||

| Genotypes of the SNP are not associated with HIV genotypic drug resistance when treated with an EFV- containing regimen. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 16267764] |

||

| 2) 983T>C | rs28399499 NM_000767.4:c.983T>C NP_000758.1:p.Ile328Thr |

The CC and/or CT genotype are associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations and drug exposure compared to the TT genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 24080498, 23080225, 18281305, 22927450, 20860463, 22481606] |

| No significant difference was found with EFV concentrations between the CT and TT genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 19371316, 19779319, 19239339] |

||

| CC and CT were not associated with risk of immunological failure or CNS toxicity as compared to the TT genotype in Ghanaian patients treated with EFV. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 24080498] |

||

| Genotype TT is associated with an increased risk of CNS side effects. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 24517233] |

||

| 3) 785A>G | rs2279343 NM_000767.4:c.785A>G NP_000758.1:p.Lys262Arg |

The GG genotype is associated with increased EFV concentrations as compared to the AA genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 23399569, 23254426, 20441246, 22481606] |

| The AG genotype is associated with increased EFV concentrations as compared to the AA genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 23399569, 23254426] |

||

| Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with EFV concentrations. |

PK | [PMID: 20625352] |

||

| 4) g.18492T>C |

rs2279345 | Genotypes CC and CT are associated with lower EFV plasma concentrations as compared to the TT genotype. Removing the potential influence of other underlying CYP2B6 SNPs, this association is maintained when examining only patients with a CYP2B6*1/*1 haplotype background (determined by genotyping 7 SNPs [PMID: 24477223, 24293076], and patients co-infected with TB with a CYP2B6*1/*1 haplotype background [PMID: 24492364]. |

PK | [PMID: 24477223, 24293076, 24492364, 23254426] |

| 5) g.27103G>A |

rs36118214 NM_000767.4:c.1294+586G>A NG_007929.1:g.27103G>A |

Genotype AA is associated with significantly lower EFV plasma levels as compared to the AG or GG genotype. This association was maintained amongst extensive metabolizers (those with rs3745274 genotype GG or rs28399499 genotype TT, removing the influence of variant alleles of these two SNPs). Though the clinical relevance cannot be determined in such a small patient group, an individual with rs36118214 genotype AA, rs1872121 genotype AA and rs12721649 genotype AG displayed extremely low EFV plasma concentrations at both week 2 and 4 of anti- retroviral treatment and experienced virologic failure at week 24. |

PK | [PMID: 19659438] |

| 6) 1459C>T | rs3211371 Arg487Cys NP_000758.1 NM_000767.4 |

Genotypes of this SNP are not significantly associated with EFV plasma concentrations or exposure. |

PK | [PMID: 18281305, 16267764, 23254426, 16433869, 23399569] |

| 7) 485-18C>T | rs4803419 NM_000767.4 : 485-18C>T |

In patients without variant alleles at rs3745274 (516C>T) and rs28399499 (983T>C), allele T was associated with higher median estimated EFV Cmin values though the effect size was smaller than the rs3745274 T allele. |

PK | [PMID: 23080225] |

| 8) 64C>T | rs8192709 (Arg22Cys : NP_000758.1, 64C>T : NM_000767.4) |

Genotype CC is associated with higher EFV concentrations (higher mid-dose EFV plasma concentrations at 12 weeks) in Thai patients. |

PK | [PMID: 23399569] |

| Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with EFV plasma concentrations (after at least 4 weeks of treatment or 12 hours after dosing) in Thai patients. |

PK | [PMID: 23254426] |

||

| 9) 136A>G | rs35303484 CYP2B6*11, NM_000767.4:c.136A>G |

In a Belgian cohort of 50 patients, only one patient had the AG genotype, with no patients with the GG genotype, and no significant association was seen in variability of minimum plasma or PBMC concentrations of EFV compared to the AA genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 20860463] |

| Genotypes of this SNP are not significantly associated with neurotoxicity syndromes (sleep disorders, hallucinations and cognitive effects) when treated with EFV-containing ART. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23734829] |

||

| 10) CYP2B6*6 |

According to CYP nomenclature, *6A is defined as 516G>T and 785A>G. |

Diplotypes *1/*6, *5/*6 and *6/*6 are associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations and decreased clearance, and *1/*1 is associated with low EFV plasma concentrations. |

PK | [PMID: 23254426, 23399569, 24142869, 25096076, 20952418] |

| Significantly lower CYP2B6 protein is observed in microsomes from Caucasians with CYP2B6 genotypes *1/*5, *1/*6, *5/*6, *6/*6 compared to *1/*1, correlating with significantly lower EFV 8-hydroxylation in *6/*6 samples. |

PK | [PMID: 17559344] |

||

1) 516G>T, rs3745274

A large number of studies have investigated the effect of the CYP2B6 516G>T SNP on EFV PK, efficacy and side effects, and it is the most investigated variant in relation to the EFV PK pathway. The T allele of this polymorphism is present in several CYP2B6 haplotypes: *6A-C, *7A, *7B, *9, *13A, *13B, *19, *20, *26, *34, *36, *37, *38 [36]. Studies using human liver samples suggest that it results in a CYP2B6 mRNA splice variant that lacks exons 4 to 6 (named SV1) and consequently results in lower levels of functional CYP2B6 mRNA [37]. Correlating with its effect on CYP2B6 expression, the T allele is associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations and median estimated Cmin values in HIV patients as compared to patients with the G allele [9, 38, 39].

Numerous studies have reported an association in HIV-infected patients between the TT genotype and increased EFV plasma concentrations, reduced clearance, or increased exposure to drug compared to patients with the GG and/or GT genotype (Table 1). The TT genotype is more common in African-Americans and Blacks than in European-Americans or Caucasians, and this may underlie differences seen in EFV plasma concentrations between these populations [40, 41]. Patients with the GT genotype also have increased EFV plasma concentrations and exposure as compared to patients with the GG genotype (Table 1). Moreover, a gene-dose effect is observed in many studies, with EFV clearance following the pattern TT<GT<GG, and EFV concentrations following the pattern TT>GT>GG [40, 42]. The TT and GT genotypes are also associated with higher intracellular peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) EFV concentrations and exposure as compared to the GG genotype (Table 1).

Clifford et al showed that EFV-treated patients experienced significantly more CNS symptoms during the first week of treatment as compared to the non-EFV group, but differences between the groups decreased rapidly and were no longer significant by four weeks of treatment [43]. The clinical relevance of increased exposure to EFV in HIV patients with the T allele has been investigated; however, results remain unclear for an association with toxicity, treatment termination, or efficacy, with some studies finding a significant association, while others do not (Table 1).

Genotyping for this variant may be helpful for individualizing EFV dosages in some situations. In one cohort of HIV-infected children the GG genotype was associated with a 50-70% probability of developing sub-therapeutic EFV plasma concentrations, and patients with the GG genotype required a higher dose adjustment [44]. Conversely, Taiwanese patients with the GT or TT genotype were at a significantly increased risk of plasma EFV concentrations associated with toxicity (>4 mg/L) - two patients discontinued EFV treatment due to neurotoxic side effects, and both had EFV plasma levels above 4mg/L [45].

It has been proposed that CYP2B6 genotyping could be used as a screen to identify individuals who may be either slow or fast metabolizers of EFV and may benefit the most from early therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), in order to optimize dosage as a function of exposure before or during the initiation of drug therapy [35, 46]. For example, one retrospective study reported that therapeutic dose monitoring and dose reduction in 31 patients with one or two 516 T alleles from a standard 600 mg/day dose of EFV to 400 mg/day, reduced the mean EFV Cmin (5.7 +/−3.4 mg/l at 600 mg/day) to within therapeutic range (2.39 +/− 1.28 mg/l at 400 mg/day) [47]. The authors also report that decreasing dosage in those patients also correlated with a decrease in the percentage of patients reporting CNS adverse events (from 89.3% to 9.7%), an increase in CD4+ lymphocyte counts (from 483.9-×106 cells/ μl to 600.8 × 106 cells/μl), and an increase in the percentage of patients with undetectable HIV viral load (from 93.5% to 100%.) Interestingly, all of the patients with the 516 T/T genotype required a further reduction to 200 mg/day EFV, supporting reduction in EFV dose for slow-metabolizers [47]. An important caveat before considering dose adjustment based on pharmacogenetic testing is that EFV and other anti-retrovirals are prescribed as part of a more complex regimen (ART and HAART) and may be administered as part of a fixed-dose co-formulation.

In conclusion, there is a clear association between the CYP2B6 516G>T variant and EFV plasma concentrations, although a lack of a clear relationship between this variant and response to EFV treatment may indicate a wide therapeutic window, as well as the complexities of drug-drug interactions of an anti-HIV regimen [48].

2) 983T>C, rs28399499

The C allele is the sole variant of the *18 allele and is also present in CYP2B6*16 (along with 785A>G). The C allele is associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations compared to the T allele [38]. Genotype CC and/or CT have been reported to be associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations and drug exposure compared to the TT genotype in several studies; however, other studies report no significant difference in EFV concentrations between the CT genotype and TT genotype (Table 1). Adjustment for the CYP2B6 516G>T genotype may be required for an association to be observed between estimated Cmin EFV with 983T>C (as was shown with trough EFV concentrations in [39]). Another factor influencing the discrepancy between studies may be the low or absent allele frequency of C in some populations: the C allele was found at a frequency of 0.05-0.08 in African, Black, or African-American populations but was not identified in Caucasian, Asian, or Chilean populations [9, 38, 49, 50]. The clinical relevance of this polymorphism is unclear. In a cohort of 170 Black and Caucasian individuals, the only two patients with the CC genotype were withdrawn from EFV-containing HAART therapy due to toxicity [38]. On the other hand, CC and CT genotypes were not associated with risk of immunological failure or central nervous system (CNS) toxicity as compared to the TT genotype in Ghanian patients treated with EFV [51].

CYP2A6 variants

Variants within the CYP2A6 gene have been associated with EFV plasma concentrations, though the clinical relevance of this effect is not clear (Table 2). An association between rs28399433 (c.-48A>C) genotypes AC and CC with increased EFV plasma concentrations, as compared to the AA genotype, has been observed in several studies, whereas others report no association with this SNP and EFV plasma levels (Table 2). As compared to CYP2B6, CYP2A6 is a minor player in EFV metabolism and associations between CYP2A6 polymorphisms and EFV PK parameters may be dependent on a patient’s underlying CYP2B6 genotype. For example, in Thai patients with the CYP2B6*1/*1 genotype (excluding patients with variant alleles at positions CYP2B6 rs8192709, rs3826711, rs3745274, rs2279343, rs3211369, rs3211371, rs8192719), CYP2A6 rs28399433 genotypes were not significantly associated with EFV plasma concentrations [12]. This was confirmed in a separate genomewide association study (GWAS) in 856 individuals that found no association between rs28399433 and estimated plasma trough concentrations of EFV [39]. However, when investigating only individuals with a CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotype (defined by genotypes 516TT, or 516T/983C or 983CC of two SNPs rs3745274 and rs28399499) a significant association was observed between the CYP2A6 rs28399433 AC genotype and higher EFV plasma concentrations (as compared to AA genotype) [52]. The clinical relevance of this SNP on EFV treatment is unclear since no association with immunological failure, virologic response, or CNS toxicity has been reported (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of EFV PGx associations for variants in the CYP2A6 gene

| Variant common name |

Variant mapping informationa |

Association with EFV in HIV-infected patientsa |

Association type |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1) −48T>G (also referred to as *9) |

rs28399433 NM_000762.5:c.-48T>G Complemented alleles: A>C. |

Genotypes AC and/or CC are associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations, as compared to the AA genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 24080498, 19659438, 24729586] |

| Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with EFV plasma levels. |

PK | [PMID: 24316028, 23080225, 24477223] |

||

| Genotypes of this SNP are not significantly associated with neurotoxicity syndromes (sleep disorders, hallucinations and cognitive effects) when treated with EFV- containing ART. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23734829] |

||

| No association was found between the genotypes AC and CC and risk of immunological failure at an average follow-up of 66 months or central nervous system (CNS) toxicity as compared to the AA genotype in retrospective analysis of medical records. |

Efficacy/ toxicity |

[PMID: 24080498] |

||

| No significant association with virologic response at 48 weeks of treatment with an EFV-containing anti- retroviral regimen. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 24695352] |

||

|

2)

CYP2A6*9 and CYP2A6*17 |

rs8192726 NM_000762.5:c.493+23G>T also described as 1836G>T Complemented alleles: C>A. and rs28399454 NM 000762.5:c.1093G>A NP_000753.3:p.Val365Met (also described as g.5056G>A) Complemented alleles: C>T. |

rs8192726 allele A and rs28399454 allele T are predictive of EFV plasma concentration. |

PK | [PMID:19779319, 19371316] |

| rs8192726 genotypes or rs28399454 genotypes are not associated with plasma or PBMC concentrations of EFV. |

PK | [PMID: 23172109, 20860463] |

||

| Genotypes of the rs28399454 SNP are not significantly associated with neurotoxicity syndromes (sleep disorders, hallucinations and cognitive effects) when treated with EFV- containing ART. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23734829] |

||

|

3) 1436T>G |

rs12460590 NM 000764.2:c.1436T>G NP_000755.2:p.Val479Gly Complemented alleles: A>C. |

This SNP contributed significantly to EFV plasma levels in univariate regression analysis, but not multivariate analysis, in 62 Rwandan patients being co-treated for HIV and TB infection. |

PK | [PMID: 24316028] |

The CYP2A6 gene is found on the minus chromosomal strand, alleles for the associations outlined here have been complemented to the plus chromosomal strand.

UGT2B7 variants

Several variants within the UGT2B7 gene have been investigated for associations with EFV PK parameters, toxicity or immunological failure, though most studies report no significant association (Table 3). Again, considering CYP2B6 genotype may be important for revealing an association with other variants; in patients with an underlying CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotype the UGT2B7 rs28365062 genotype GG was associated with higher EFV plasma concentrations, and this SNP along with CYP2A6 rs28399433 A>C explained 21% variance in EFV plasma concentrations in these patients using a multivariate linear regression model [52].

Table 3.

Summary of EFV PGx associations for variants in the UGT2B7 gene

| Variant common name |

Variant mapping information |

Association with EFV in HIV-infected patients |

Association type |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.802T>C | rs7439366 NM 001074.2:c.802T>C NP_001065.2:p.Tyr268His |

Alleles or genotypes of this SNP are not significantly associated with EFV plasma concentrations. |

PK | [PMID: 24080498, 23172109]. |

| No association was found for risk of immunological failure or neurotoxicity syndromes in Ghanaian patients with HIV treated with EFV-containing anti- retroviral regimen. |

Toxicity/ efficacy |

[PMID: 24080498] | ||

| c.802T>C and c.801A>T |

rs7439366 NM 001074.2:c.802T>C NP_001065.2:p.Tyr268His rs7438284 NM 001074.2:c.801A>T NP_001065.2:p.Pro267Pro |

Combined analysis of alleles of these two variants found no association with plasma or PBMC EFV concentrations in a cohort of 50 patients in Belgium. |

PK | [PMID: 20860463] |

| c.735A>G | rs28365062 NM 001074.2:c.735A>G NP 001065.2:p.Thr245Thr |

Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with plasma or PBMC EFV concentrations. |

PK | [PMID: 20860463, 24080498, 23172109] |

| Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with immunological failure or neurotoxicity syndromes in Ghanian patients with HIV treated with EFV- containing anti-retroviral regimen |

Toxicity/ efficacy |

[PMID: 24080498] | ||

| In patients with an underlying CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotype (defined by genotypes 516TT, or 516T/983C or 983CC of the two SNPs rs3745274 and rs28399499), rs28365062 genotype GG was associated with higher EFV plasma concentrations. |

PK | [PMID: 24729586] |

CYP3A5 and CYP3A4 variants

Associations for variants in the CYP3A5 and CYP3A4 genes can be seen in Table 4. In patients with the CYP2B6*1/*1 genotype (excluding patients with variant alleles at positions CYP2B6 rs8192709, rs3826711, rs3745274, rs2279343, rs3211369, rs3211371, rs8192719), rs776746 (CYP3A5), rs28371759 (CYP3A4) or rs2740574 (CYP3A4) genotypes were not found to be significantly associated with EFV plasma concentrations in 100 Thai HIV patients [12].

Table 4.

Summary of EFV PGx associations for variants in the CYP3A4 and CYP3A5

| Variant common name |

Variant mapping informationa |

Association with EFV in HIV-infected patientsa |

Association type |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) CYP3A 5 6986A>G |

rs776746 Present in CYP3A5 alleles *3A-L and *9 NC 000007.14:g.99672916 T>C Complemented alleles: T>C. |

Lower EFV plasma concentrations and higher clearance in patients with the CC or CT genotype compared to those with the TT genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 15622315] |

| No association with plasma or PBMC EFV concentrations, or EFV plasma exposure. |

PK | [PMID: 20625352, 23080225, 24316028, 16267764, 24477223] |

||

| 2) CYP3A5 713G>A |

Complemented alleles: C>T. | Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with EFV plasma exposure. |

PK | [PMID: 16267764] |

| 3) CYP3A4 -392G>A |

rs2740574 NM_017460.5:c.−392G>A Complemented alleles: C>T. |

Higher EFV plasma concentrations were observed in patients with the CC or CT genotype compared to TT in univariate analysis in n=152 subjects. |

PK | [PMID: 15622315] |

| No association was found between genotypes of this SNP and CC and CT and EFV plasma exposure in n=367 subjects |

PK | [PMID: 16267764] |

||

| This SNP contributed significantly to EFV plasma levels in univariate regression analysis, but not multivariate analysis, in 62 Rwandan patients being co-treated for HIV and TB infection. |

PK | [PMID: 24316028] |

||

| No significant association with virologic response at 48 weeks was found in 359 HIV patients treated with an EFV-containing anti-retroviral regimen. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 24695352] |

The CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genes are found on the minus chromosomal strand, alleles for the associations outlined here have been complemented to the plus chromosomal strand.

NR1I3 variants

A SNP (rs2307424) that results in a G>A substitution in the NR1I3 (CAR) gene has been investigated for effects in patients treated with EFV (Table 5). In a cohort of Chilean patients with HIV, the G allele was associated with higher EFV plasma concentrations, and along with CYP2B6 rs3745274 allele A, was a statistically significant predictor of EFV plasma concentrations in multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis [9]. The A allele may therefore enhance NR1I3 activity, resulting in increased expression of CYP2B6 and thus reduced EFV plasma concentrations [9]. Genotype GG was independently associated with increased risk of discontinuation of EFV treatment within 3 months of treatment along with other risk factors in a mixed population cohort [53]. In Ghanaian patients, a study found no statistically significant association between this polymorphism and EFV plasma concentrations, CNS toxicity, or risk of immunological failure [51]. Two other studies also reported no significant associations between rs2307424 G>A and plasma concentrations of EFV after taking three CYP2B6 polymorphisms into account [39, 52].

Table 5.

Summary of EFV PGx associations for variants in the NR1I3 gene

| Variant common name |

Variant mapping informationa |

Association with EFV in HIV-infected patientsa |

Associati on type |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.540C>T | rs2307424 NM_001077469.2:c.540C>T NP_001070937.1:p.Pro180Pro Complemented alleles: G>A. |

The G allele is associated with higher EFV plasma concentrations. |

PK | [PMID: 23172109] |

| Genotype GA and AA are not associated with significant differences in EFV plasma concentrations compared to the GG genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 23080225, 23173844, 24080498] |

||

| Genotype GG is associated with increased risk of discontinuation of EFV treatment within 3 months of treatment. |

Toxicity/ efficacy |

[PMID: 21715435] | ||

| Genotype GA and AA are not associated with risk of central nervous system toxicity or immunological failure compared to the GG genotype. |

Toxicity/ efficacy |

[PMID: 24080498] | ||

| rs3003596 |

NM_001077469.2:c.239- 1089T>C Complemented alleles: A>G. |

Genotype GG and AG are associated with lower EFV plasma concentrations compared to the AA genotype. |

PK | [PMID: 23173844] |

| Genotypes of this SNP are not significantly associated with neurotoxicity syndromes (sleep disorders, hallucinations and cognitive effects) when treated with EFV- containing ART. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23734829] |

The NR1I3 gene is found on the minus chromosomal strand, alleles for the associations outlined here have been complemented to the plus chromosomal strand.

Conversely, the NR1I3 rs3003596 genotype GG has been associated with lower EFV plasma concentrations compared to the AA and AG genotypes (Table 5). When stratifying for the CYP2B6 516G>T genotype, the significant effect is only seen in patients with the CYP2B6 c.516 TT genotype [54]. The same study found no statistically significant association with other NR1I3 or NR1I2 SNPs and EFV plasma concentrations, including rs2307424 [54].

ABCB1 variants

ABCB1 (P-gp, MDR1) has not been shown to have a direct role in EFV transport; however, several studies have investigated the effects of EFV on ABCB1 expression and the effects of ABCB1 polymorphisms on EFV PK (Table 6). PBMC mRNA expression of ABCB1 was significantly reduced at day 14 from day 1 of EFV treatment in healthy volunteers, though P-gp enzymatic activity in PBMCs was not altered by treatment [55, 56]. Polymorphisms in ABCB1 may influence the PK of drugs taken concomitantly with EFV, and thus may affect EFV levels via drug-drug interactions. Mixed results are reported for the effect of the rs1045642 SNP on EFV PK and toxicity, but for associations related to drug efficacy, the A allele seems to be associated with favorable outcomes in patients with HIV (Table 6). In contrast, an association between the A allele and a lower increase in CD4+ T cell count was reported in Belgian patients after initiation of EFV-containing therapy [57]. More studies are required to evaluate the clinical relevance of ABCB1 variants on response to treatment that includes EFV.

Table 6.

Summary of EFV PGx associations for variants in the ABCB1 gene

| Variant common name |

Variant mapping informationa |

Association with EFV in HIV-infected patientsa |

Association type |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1)3435 T>C/A |

rs1045642 NM_000927.4:c.3435 T>C NM_000927.4:c.3435 T>A NP_000918.2:p.Ile11 45= Complemented alleles: A>G/T. |

Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with EFV minimum plasma concentrations, plasma drug exposure, oral clearance, apparent volume of distribution or PBMC EFV concentrations. |

PK | [PMID: 20860463, 15622315, 16267764, 20625352, 24145522] |

| Genotype AA is associated with increased clearance of EFV compared to AG, and genotype GG is associated with decreased clearance as compared to genotype AG. |

PK | [PMID: 12545140] |

||

| Allele A is associated with an increased likelihood of toxicity-related treatment failure when treated with an EFV-containing regimen. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 16267764]– this variant was in LD with rs2032582. |

||

| Allele A is associated with a reduced risk of hepatotoxicity during antiretroviral therapy when treated with EFV or nevirapine (patients were combined) as compared to allele G. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 16912956] |

||

| Genotypes of this SNP are not significantly associated with neurotoxicity syndromes (sleep disorders, hallucinations and cognitive effects) when treated with EFV-containing ART. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23734829] |

||

| The AA genotype is associated with a lower likelihood of virologic failure compared to the AG/GG genotype in patients receiving an EFV-containing regimen. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 16267764] |

||

| Allele A is associated with a reduced likelihood of emerging viral drug resistance in patients receiving an EFV-containing regimen. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 16267764]. |

||

| Genotype AA is associated with an increased likelihood of favorable virologic responses and a higher increase in CD4+ T cell count when treated with EFV or nelfinavir compared to other genotypes |

Efficacy | [PMID: 11809184]. |

||

| Allele A is not associated with a reduced response to EFV in patients with AIDS. |

Efficacy | [PMID: 20662624] |

||

| A allele and a lower increase in CD4+ T cell count in Belgian patients after initiation of EFV-containing therapy (a multiple linear regression model). |

Efficacy | [PMID: 20860463] |

||

| 2) *193A>G | rs3842 NM_000927.4:c.*193 A>G Complemented alleles: T>C. |

The C allele and Asian origin was associated with intra- individual variability in EFV accumulation ratio (EFV PBMC concentration/minimum concentration of EFV) in a multiple linear regression model |

PK | [PMID: 20860463] |

| This SNP was associated with EFV metabolism in co- variate analysis. |

PK | [PMID: 24497997] |

||

| Genotypes of this SNP are not significantly associated with neurotoxicity syndromes (sleep disorders, hallucinations and cognitive effects) when treated with EFV-containing ART. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23734829] |

||

| 3)2677 A>C/T |

rs2032582 NM_000927.4:c.2677 T>A NM_000927.4:c.2677 T>G NP_000918.2:p.Ser89 3Ala NP_000918.2:p.Ser89 3Thr Complemented alleles: A>C/T. |

Genotypes of this SNP are not associated with EFV plasma concentrations, plasma exposure or PBMC concentrations in HIV patients. |

PK | [PMID: 16267764, 20860463, 20625352, 15622315] |

| 4) 1236T>C |

rs1128503 NM_000927.4:c.1236 T>C NP_000918.2:p.Gly41 2Gly Complemented alleles: A>G. |

Genotypes of this SNP were not associated with minimum plasma or PBMC EFV concentrations in a Belgian cohort of 50 HIV patients. |

PK | [PMID: 20860463] |

The ABCB1 gene is found on the minus chromosomal strand, alleles here have been complemented to the plus chromosomal strand.

Other genes

Polymorphisms in other genes, such as CYP1A2 and HTR2A have been investigated for an association with EFV PK parameters, toxicity, or efficacy (Table 7).

Table 7.

Summary of EFV PGx associations for variants in other genes

| Gene | Variant common name |

Variant mapping information |

Association with EFV in HIV- infected patients |

Association type |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | - 739T>G |

In 62 Rwandan patients treated for both HIV and TB infection, genotype TG was associated with higher EFV plasma levels over a 6-week period as compared to patients with the TT genotype, although in multivariate analysis, none of the three CYP1A2 SNPs investigated (−739T>G, − 163C>A, and 2159G>A) contributed significantly to EFV plasma level variation. |

PK | [PMID: 24316028] |

|

| HTR2A | 102C>T | rs6313 | This variant was associated with a decreased risk of sadness when treated with EFV in multivariate regression analysis. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23859571] |

| ABCG2 | 421C>A | rs2231142 | Associated with increased risk of abnormal dreams when treated with EFV in multivariate analysis adjusted for maximum steady state plasma concentration and demographic co-variables. |

Toxicity | [PMID: 23859571] |

Multivariate analysis

It is likely that multiple polymorphisms in genes involved in EFV metabolism contribute to overall EFV plasma concentrations and resulting efficacy and toxicity outcomes. Recent studies have examined multiple factors influencing variance in EFV PK parameters; these results are summarized below.

Multiple SNPs in CYP2B6

rs3745274 c.516G>T and rs28399499 c.983T>C are the two SNPs in CYP2B6 that are most often reported to demonstrate an association with variability in EFV trough concentrations. In a cohort of Belgian patients, CYP2B6 c.516 genotype GT and TT, CYP2B6 c.983 genotype TC, and Asian origin, were all factors that contributed significantly to interindividual variability in estimated log-transformed trough EFV concentrations [57]. Moreover, CYP2B6 c.516G>T, CYP2B6 c.983T>C, BMI, and time post-dose were all significantly associated with EFV plasma concentrations in a multivariate analysis of a cohort of 174 Caucasian and Black patients on stable EFV-containing HAART [38]. Additionally, mean log EFV trough concentrations increased with the number of CYP2B6 loss-of-function alleles in Ugandan and Zimbabwean patients [58]. After correcting for c.516 G>T and c.983 T>C, an intronic polymorphism in CYP2B6, rs4803419 C>T, also showed an association with variability in EFV trough concentrations in a GWAS. Together, the three SNPs explained 33% of the interindividual variability in EFV concentrations in a cohort of n=856 in linear regression analysis [39]. Slow metabolizers (women with two 516T alleles or two 983C alleles, or one of each allele) were more likely to respond to NNRTI-based treatment (undetectable viral load up to 54 weeks after initiation) compared to fast metabolizers (no variant alleles at these positions) [59]. Conversely, some studies do not show these genotypic associations with response to EFV treatment; multiple SNP analyses examining different genotype combinations of CYP2B6 rs3745274, rs28399499 and rs4803419 found no association with virologic response at 48 weeks in 359 HIV-infected Haitian patients treated with an EFV-containing anti-retroviral regimen, or with other SNPs examined [60]. Multivariate analysis in another study in Ghanaian patients reported CYP2B6 c.516G>T (n=496), CYP2B6 c.983T>C (n=494), and body weight as independent factors associated with EFV plasma concentration; however, neither EFV plasma concentration nor SNPs could predict clinical failure in univariate analysis [51].

Multiple gene analysis

Several studies examine the effect of polymorphisms in multiple genes on EFV plasma concentration. A stepwise multiple linear regression analysis identified CYP2B6 rs3745274 c.516 genotype TT, UGT2B7*1a carrier status (no variant alleles at rs7439366 C>T or rs28365062 A>G), and CYP2A6*9 (rs8192726 C>A), or CYP2A6*17 (rs28399454 C>T) as independent predictors of EFV plasma concentration (mid-dose at weeks 4 and 8) in 94 Ghanaian patients, accounting for 45.2%, 10.1% and 8.6% of the total variance in EFV plasma concentrations, respectively [61]. Furthermore, a multivariate linear regression model including CYP2A6 rs28399433 A>C and UGT2B7 rs28365062 A>G explained 21% variance in EFV plasma concentrations in patients with the CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotype (defined by genotypes 516TT, or 516T/983C, or 983CC of two SNPs: rs3745274 and rs28399499). In addition, when coupled with CYP2B6 rs28399499 T>C the variance explained reached 22% [52].

Similarly, in 207 Chilean HIV patients, multivariate stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that the CYP2B6 rs3745274 allele T and NR1I3 rs2307424 allele G were significant predictors for EFV plasma concentrations [9]. More patients were above the suggested minimum toxic concentration of plasma EFV (4μg/mL) who had three to four high EFV concentration-associated alleles (CYP2B6 rs3745274 allele T and NR1I3 rs2307424 allele G) than those with zero, one, or two of these alleles. Conversely, more patients were below the suggested minimum effective concentration (1μg/mL) that had zero or one of these alleles compared to those with three or four [9]. Examining patients who were within the EFV therapeutic range (1-4 μg/mL), more were carriers of one or two of these variants [9]. Furthermore, in a separate cohort from the German Competence Network for HIV/AIDS, CYP2B6 rs3745274 allele T and NR1I3 rs2307424 allele G were classified as ‘discontinuation-associated’ alleles because the higher the number of these alleles possessed by the patients, the higher the rate of treatment discontinuation due to increased EFV plasma toxicity [53]. Additionally, multivariate backward logistic regression found that CYP2B6 rs3745274 genotype TT, NR1I3 rs2307424 genotype GG, ethnicity, and smoking status were independently associated with the discontinuation of EFV within 3 months of treatment. In conjunction, an association was observed where patients possessing an increased number of these risk factors were more likely to discontinue treatment [53].

Genes involved in metabolism of other drugs taken concomitantly with EFV

In patients also being treated for TB infection, polymorphisms in genes involved in other drug PK pathways could also influence EFV PK. In a multivariate regression analysis of 62 patients from Rwanda being treated for HIV and TB infection, CYP2B6 c.516G>T, CYP2B6 c.983T>C, and CYP2A6 c.1093G>A contributed 43%, 29%, and 27% of the total variance in EFV plasma levels, respectively [50]. Another study took into account the NAT2 genotype, and found that patients with the CYP2B6 c.516G>T genotype TT and a NAT2 slow acetylator genotype (two “slow” alleles NAT2*5, *6 or *7 determined by genotyping rs1801280, rs1801279, rs1799930 and rs1799931) had the lowest apparent EFV clearance when treated concomitantly with anti-TB drugs [62]. On the other hand, patients with the CYP2B6 c.516G>T genotype GG with the NAT2 rapid acetylator genotype had the highest levels of clearance [62]. When TB treatment was discontinued, EFV plasma concentrations decreased in NAT2 slow acetylators and rose in NAT2 rapid acetylators [62].

Conclusions

Large variability in EFV plasma concentrations exists between patients given the same dose of the drug. Polymorphisms in genes underlying EFV metabolism have been associated with EFV exposure; however, the clinical consequences of these variants are unclear. Genotyping and inclusion of multiple variables may help establish the dose of EFV required by an individual to achieve therapeutic levels. Personalizing EFV dosages for HIV treatment may help to reduce EFV exposure as well as CNS toxicity in individuals with the CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotype. However, EFV is often co-formulated with other anti-retroviral agents in a fixed dose regimen for HAART and this should be considered before genotype-based dose adjustment.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the NIH/NIGMS (R24 GM61374).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

RBA and TEK are stockholders in Personalis, Inc.

References

- 1.Naidoo P, Chetty VV, Chetty M. Impact of CYP polymorphisms, ethnicity and sex differences in metabolism on dosing strategies: the case of efavirenz. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arts EJ, Hazuda DJ. HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a007161. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yimer G, Ueda N, Habtewold A, Amogne W, Suda A, Riedel KD, Burhenne J, Aderaye G, Lindquist L, Makonnen E, Aklillu E. Pharmacogenetic & pharmacokinetic biomarker for efavirenz based ARV and rifampicin based anti-TB drug induced liver injury in TB-HIV infected patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukonzo JK, Okwera A, Nakasujja N, Luzze H, Sebuwufu D, Ogwal-Okeng J, Waako P, Gustafsson LL, Aklillu E. Influence of efavirenz pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics on neuropsychological disorders in Ugandan HIV-positive patients with or without tuberculosis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez Martin A, Cabrera Figueroa S, Cruz Guerrero R, Hurtado LP, Hurle AD, Carracedo Alvarez A. Impact of pharmacogenetics on CNS side effects related to efavirenz. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:1167–1178. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lubomirov R, Colombo S, di Iulio J, Ledergerber B, Martinez R, Cavassini M, Hirschel B, Bernasconi E, Elzi L, Vernazza P, et al. Association of pharmacogenetic markers with premature discontinuation of first-line anti-HIV therapy: an observational cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:246–257. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stahle L, Moberg L, Svensson JO, Sonnerborg A. Efavirenz plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients: inter- and intraindividual variability and clinical effects. Ther Drug Monit. 2004;26:267–270. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200406000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marzolini C, Telenti A, Decosterd LA, Greub G, Biollaz J, Buclin T. Efavirenz plasma levels can predict treatment failure and central nervous system side effects in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 2001;15:71–75. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortes CP, Siccardi M, Chaikan A, Owen A, Zhang G, la Porte CJ. Correlates of efavirenz exposure in Chilean patients affected with human immunodeficiency virus reveals a novel association with a polymorphism in the constitutive androstane receptor. Ther Drug Monit. 2013;35:78–83. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e318274197e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burger D, van der Heiden I, la Porte C, van der Ende M, Groeneveld P, Richter C, Koopmans P, Kroon F, Sprenger H, Lindemans J, et al. Interpatient variability in the pharmacokinetics of the HIV non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz: the effect of gender, race, and CYP2B6 polymorphism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo S, Telenti A, Buclin T, Furrer H, Lee BL, Biollaz J, Decosterd LA, Swiss HIVCS Are plasma levels valid surrogates for cellular concentrations of antiretroviral drugs in HIV-infected patients? Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:332–338. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000211807.74192.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sukasem C, Chamnanphon M, Koomdee N, Santon S, Jantararoungtong T, Prommas S, Puangpetch A, Manosuthi W. Pharmacogenetics and clinical biomarkers for subtherapeutic plasma efavirenz concentration in HIV-1 infected Thai adults. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2014 doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-13-rg-077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gounden V, van Niekerk C, Snyman T, George JA. Presence of the CYP2B6 516G> T polymorphism, increased plasma Efavirenz concentrations and early neuropsychiatric side effects in South African HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michaud V, Bar-Magen T, Turgeon J, Flockhart D, Desta Z, Wainberg MA. The dual role of pharmacogenetics in HIV treatment: mutations and polymorphisms regulating antiretroviral drug resistance and disposition. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:803–833. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward BA, Gorski JC, Jones DR, Hall SD, Flockhart DA, Desta Z. The cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) is the main catalyst of efavirenz primary and secondary metabolism: implication for HIV/AIDS therapy and utility of efavirenz as a substrate marker of CYP2B6 catalytic activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:287–300. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desta Z, Saussele T, Ward B, Blievernicht J, Li L, Klein K, Flockhart DA, Zanger UM. Impact of CYP2B6 polymorphism on hepatic efavirenz metabolism in vitro. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:547–558. doi: 10.2217/14622416.8.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogburn ET, Jones DR, Masters AR, Xu C, Guo Y, Desta Z. Efavirenz primary and secondary metabolism in vitro and in vivo: identification of novel metabolic pathways and cytochrome P450 2A6 as the principal catalyst of efavirenz 7-hydroxylation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:1218–1229. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.031393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mutlib AE, Chen H, Nemeth GA, Markwalder JA, Seitz SP, Gan LS, Christ DD. Identification and characterization of efavirenz metabolites by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and high field NMR: species differences in the metabolism of efavirenz. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1319–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bae SK, Jeong YJ, Lee C, Liu KH. Identification of human UGT isoforms responsible for glucuronidation of efavirenz and its three hydroxy metabolites. Xenobiotica. 2011;41:437–444. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2011.551849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji HY, Lee H, Lim SR, Kim JH, Lee HS. Effect of efavirenz on UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1, 1A4, 1A6, and 1A9 activities in human liver microsomes. Molecules. 2012;17:851–860. doi: 10.3390/molecules17010851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho DY, Ogburn ET, Jones D, Desta Z. Contribution of N-glucuronidation to efavirenz elimination in vivo in the basal and rifampin-induced metabolism of efavirenz. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1504–1509. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00883-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belanger AS, Caron P, Harvey M, Zimmerman PA, Mehlotra RK, Guillemette C. Glucuronidation of the antiretroviral drug efavirenz by UGT2B7 and an in vitro investigation of drug-drug interaction with zidovudine. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1793–1796. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pere P, Gillet P, Gaucher A. Stress fractures. Fatigue fractures and bone insufficiency fractures. Presse Med. 1990;19:694–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faucette SR, Zhang TC, Moore R, Sueyoshi T, Omiecinski CJ, LeCluyse EL, Negishi M, Wang H. Relative activation of human pregnane X receptor versus constitutive androstane receptor defines distinct classes of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 inducers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:72–80. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.112136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faucette SR, Sueyoshi T, Smith CM, Negishi M, Lecluyse EL, Wang H. Differential regulation of hepatic CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 genes by constitutive androstane receptor but not pregnane X receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1200–1209. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hariparsad N, Nallani SC, Sane RS, Buckley DJ, Buckley AR, Desai PB. Induction of CYP3A4 by efavirenz in primary human hepatocytes: comparison with rifampin and phenobarbital. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:1273–1281. doi: 10.1177/0091270004269142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adkins JC, Noble S. Efavirenz. Drugs. 1998;56:1055–1064. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856060-00014. discussion 1065-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svard J, Spiers JP, Mulcahy F, Hennessy M. Nuclear receptor-mediated induction of CYP450 by antiretrovirals: functional consequences of NR1I2 (PXR) polymorphisms and differential prevalence in whites and sub-Saharan Africans. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:536–549. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f52f0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Granda BW, Giancarlo GM, Duan SX, Daily JP, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 isoforms by nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41:85–91. doi: 10.1177/00912700122009728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu C, Desta Z. In vitro analysis and quantitative prediction of efavirenz inhibition of eight cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes: major effects on CYPs 2B6, 2C8, 2C9 and 2C19. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;28:362–371. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-12-rg-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Q, Okusanya OO, Smith PF, Dicenzo R, Slish JC, Catanzaro LM, Forrest A, Morse GD. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2005;1:473–485. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nanzigu S, Eriksen J, Makumbi F, Lanke S, Mahindi M, Kiguba R, Beck O, Ma Q, Morse GD, Gustafsson LL, Waako P. Pharmacokinetics of the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz among HIV-infected Ugandans. HIV Med. 2012;13:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngaimisi E, Mugusi S, Minzi OM, Sasi P, Riedel KD, Suda A, Ueda N, Janabi M, Mugusi F, Haefeli WE, et al. Long-term efavirenz autoinduction and its effect on plasma exposure in HIV patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:676–684. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Habtewold A, Amogne W, Makonnen E, Yimer G, Riedel KD, Ueda N, Worku A, Haefeli WE, Lindquist L, Aderaye G, et al. Long-term effect of efavirenz autoinduction on plasma/peripheral blood mononuclear cell drug exposure and CD4 count is influenced by UGT2B7 and CYP2B6 genotypes among HIV patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2350–2361. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cabrera Figueroa S, Fernandez de Gatta M, Hernandez Garcia L, Dominguez-Gil Hurle A, Bustos Bernal C, Sepulveda Correa R, Garcia Sanchez MJ. The convergence of therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacogenetic testing to optimize efavirenz therapy. Ther Drug Monit. 2010;32:579–585. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181f0634c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. [accessed 14th October 2014];The Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database. http://www.cypalleles.ki.se/cyp2b6.htm.

- 37.Hofmann MH, Blievernicht JK, Klein K, Saussele T, Schaeffeler E, Schwab M, Zanger UM. Aberrant splicing caused by single nucleotide polymorphism c.516G>T [Q172H], a marker of CYP2B6*6, is responsible for decreased expression and activity of CYP2B6 in liver. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:284–292. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wyen C, Hendra H, Vogel M, Hoffmann C, Knechten H, Brockmeyer NH, Bogner JR, Rockstroh J, Esser S, Jaeger H, et al. Impact of CYP2B6 983T>C polymorphism on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:914–918. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holzinger ER, Grady B, Ritchie MD, Ribaudo HJ, Acosta EP, Morse GD, Gulick RM, Robbins GK, Clifford DB, Daar ES, et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma efavirenz pharmacokinetics in AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocols implicates several CYP2B6 variants. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22:858–867. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835a450b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas DW, Ribaudo HJ, Kim RB, Tierney C, Wilkinson GR, Gulick RM, Clifford DB, Hulgan T, Marzolini C, Acosta EP. Pharmacogenetics of efavirenz and central nervous system side effects: an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group study. AIDS. 2004;18:2391–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powers V, Ward J, Gompels M. CYP2B6 G516T genotyping in a UK cohort of HIV-positive patients: polymorphism frequency and influence on efavirenz discontinuation. HIV Med. 2009;10:520–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saitoh A, Fletcher CV, Brundage R, Alvero C, Fenton T, Hsia K, Spector SA. Efavirenz pharmacokinetics in HIV-1-infected children are associated with CYP2B6-G516T polymorphism. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:280–285. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318040b29e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clifford DB, Evans S, Yang Y, Acosta EP, Ribaudo H, Gulick RM, As Study T Long-term impact of efavirenz on neuropsychological performance and symptoms in HIV-infected individuals (ACTG 5097s) HIV Clin Trials. 2009;10:343–355. doi: 10.1310/hct1006-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ter Heine R, Scherpbier HJ, Crommentuyn KM, Bekker V, Beijnen JH, Kuijpers TW, Huitema AD. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenetic study of efavirenz in children: dosing guidelines can result in subtherapeutic concentrations. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:779–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee KY, Lin SW, Sun HY, Kuo CH, Tsai MS, Wu BR, Tang SY, Liu WC, Chang SY, Hung CC. Therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacogenetic study of HIV-infected ethnic chinese receiving efavirenz-containing antiretroviral therapy with or without rifampicin-based anti-tuberculous therapy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nolan D, Phillips E, Mallal S. Efavirenz and CYP2B6 polymorphism: implications for drug toxicity and resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:408–410. doi: 10.1086/499369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin AS, Gomez AI, Garcia-Berrocal B, Figueroa SC, Sanchez MC, Calvo Hernandez MV, Gonzalez-Buitrago JM, Valverde Merino MP, Tovar CB, Martin AF, Isidoro-Garcia M. Dose reduction of efavirenz: an observational study describing cost-effectiveness, pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:997–1006. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haas DW, Smeaton LM, Shafer RW, Robbins GK, Morse GD, Labbe L, Wilkinson GR, Clifford DB, D’Aquila RT, De Gruttola V, et al. Pharmacogenetics of long-term responses to antiretroviral regimens containing Efavirenz and/or Nelfinavir: an Adult Aids Clinical Trials Group Study. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1931–1942. doi: 10.1086/497610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehlotra RK, Bockarie MJ, Zimmerman PA. CYP2B6 983T>C polymorphism is prevalent in West Africa but absent in Papua New Guinea: implications for HIV/AIDS treatment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:391–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bienvenu E, Swart M, Dandara C, Ashton M. The role of genetic polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 and effects of tuberculosis co-treatment on the predictive value of CYP2B6 SNPs and on efavirenz plasma levels in adult HIV patients. Antiviral Res. 2014;102:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarfo FS, Zhang Y, Egan D, Tetteh LA, Phillips R, Bedu-Addo G, Sarfo MA, Khoo S, Owen A, Chadwick DR. Pharmacogenetic associations with plasma efavirenz concentrations and clinical correlates in a retrospective cohort of Ghanaian HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:491–499. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haas DW, Kwara A, Richardson DM, Baker P, Papageorgiou I, Acosta EP, Morse GD, Court MH. Secondary metabolism pathway polymorphisms and plasma efavirenz concentrations in HIV-infected adults with CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014 doi: 10.1093/jac/dku110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyen C, Hendra H, Siccardi M, Platten M, Jaeger H, Harrer T, Esser S, Bogner JR, Brockmeyer NH, Bieniek B, et al. Cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) polymorphisms are associated with early discontinuation of efavirenz-containing regimens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2092–2098. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swart M, Whitehorn H, Ren Y, Smith P, Ramesar RS, Dandara C. PXR and CAR single nucleotide polymorphisms influence plasma efavirenz levels in South African HIV/AIDS patients. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burhenne J, Matthee AK, Pasakova I, Roder C, Heinrich T, Haefeli WE, Mikus G, Weiss J. No evidence for induction of ABC transporters in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in humans after 14 days of efavirenz treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4185–4191. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00283-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mukonzo JK, Roshammar D, Waako P, Andersson M, Fukasawa T, Milani L, Svensson JO, Ogwal-Okeng J, Gustafsson LL, Aklillu E. A novel polymorphism in ABCB1 gene, CYP2B6*6 and sex predict single-dose efavirenz population pharmacokinetics in Ugandans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:690–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elens L, Vandercam B, Yombi JC, Lison D, Wallemacq P, Haufroid V. Influence of host genetic factors on efavirenz plasma and intracellular pharmacokinetics in HIV-1-infected patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:1223–1234. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jamshidi Y, Moreton M, McKeown DA, Andrews S, Nithiyananthan T, Tinworth L, Holt DW, Sadiq ST. Tribal ethnicity and CYP2B6 genetics in Ugandan and Zimbabwean populations in the UK: implications for efavirenz dosing in HIV infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2614–2619. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frasco MA, Mack WJ, Van Den Berg D, Aouizerat BE, Anastos K, Cohen M, De Hovitz J, Golub ET, Greenblatt RM, Liu C, et al. Underlying genetic structure impacts the association between CYP2B6 polymorphisms and response to efavirenz and nevirapine. AIDS. 2012;26:2097–2106. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283593602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haas DW, Severe P, Jean Juste MA, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. Functional CYP2B6 variants and virologic response to an efavirenz-containing regimen in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014 doi: 10.1093/jac/dku088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwara A, Lartey M, Sagoe KW, Kenu E, Court MH. CYP2B6, CYP2A6 and UGT2B7 genetic polymorphisms are predictors of efavirenz mid-dose concentration in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2009;23:2101–2106. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283319908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bertrand J, Verstuyft C, Chou M, Borand L, Chea P, Nay KH, Blanc FX, Mentre F, Taburet AM. Dependence of efavirenz- and rifampicin-isoniazid-based antituberculosis treatment drug-drug interaction on CYP2B6 and NAT2 genetic polymorphisms: ANRS 12154 study in Cambodia. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:399–408. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]