Abstract

This study tested whether relationship education (i.e., the Prevention and Relationship Education Program; PREP) can mitigate the risk of having cohabited before making a mutual commitment to marry (i.e., “pre-commitment cohabitation”) for marital distress and divorce. Using data from a study of PREP for married couples in the U.S. Army (N = 662 couples), we found that there was a significant association between pre-commitment cohabitation and lower marital satisfaction and dedication before random-assignment to intervention. After intervention, this pre-commitment cohabitation effect was only apparent in the control group. Specifically, significant interactions between intervention condition and cohabitation history indicated that for the control group, but not the PREP group, pre-commitment cohabitation was associated with lower dedication as well as declines in marital satisfaction and increases in negative communication over time. Further, those with pre-commitment cohabitation were more likely to divorce by the two-year follow up only in the control group; there were no differences in divorce based on premarital cohabitation history in the PREP group. These findings are discussed in light of current research on cohabitation and relationship education; potential implications are also considered.

Keywords: Premarital cohabitation, relationship education, marriage education, divorce, PREP, military

There is evidence that premarital cohabitation is associated with risk for divorce and marital distress (for meta analyses, see Jose, O’Leary, & Moyer, 2010), particularly among those who cohabited before having made a mutual commitment to marriage (Kline et al., 2004; Manning & Cohen, 2012; Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2009; Stanley, Rhoades, Amato, Markman, & Johnson, 2010). This study tests whether receiving marriage education can mitigate the risk associated with cohabiting before a specific mutual commitment to marriage (i.e., “pre-commitment cohabitation”).

The inertia theory (Stanley, Rhoades, & Markman, 2006) suggests that one reason why pre-commitment cohabitation is associated with poorer marital outcomes is that cohabitation makes it harder to end a relationship and therefore increases the likelihood that a poorer quality and less committed relationship may progress into marriage. We would expect that those who cohabit only after having made a mutual commitment to marry would be less likely to be subject to the potential “inertia” living together may create. Most research that has examined the distinction between cohabiting before versus after having made a mutual commitment to marriage has found that pre-commitment cohabitation is associated with a higher risk for divorce (Manning & Cohen, 2012; Stanley, Rhoades, et al., 2010) as well as lower marital satisfaction, lower dedication, poorer communication, and more aggression compared to cohabiting only after a commitment to marriage or not at all before marriage (Kline et al., 2004; Rhoades et al., 2009; Stanley, Rhoades, et al., 2010).

These types of relationship dynamics and problems are often targeted in couple-based relationship education (Markman & Rhoades, 2012). The Prevention and Relationship Education Program (PREP; Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2010), for example, teaches couples skills and principles associated with happy, healthy relationships and includes ways to communicate and handle conflict well and a focus on the importance of commitment in marriage and ways to preserve and enhance it. We believe that by targeting communication and commitment directly, PREP may reduce the link between pre-commitment cohabitation and poor marital outcomes. Although changes in commitment have rarely been examined, meta-analyses indicate that relationship education programs are generally effective at improving communication (Blanchard, Hawkins, Baldwin, & Fawcett, 2009). With regard to PREP in particular, many studies indicate its effectiveness in improving communication quality compared to no treatment or treatment-as-usual (Laurenceau, Stanley, Olmos-Gallo, Baucom, & Markman, 2004; Markman, Renick, Floyd, Stanley, & Clements, 1993; Stanley et al., 2001).

There is also evidence that relationship education programs like PREP may be most effective for couples who are considered “high risk” for marital distress or divorce. For example, couples with certain characteristics (e.g., parental divorce, those with children from prior relationships) tend to show greater improvements than those without these risk factors (e.g., Amato, 2014; Halford, Sanders, & Behrens, 2001; Petch, Halford, Creedy, & Gamble, 2012).

Based on this prior work on premarital cohabitation and relationship education, we hypothesized that PREP would mitigate the risk for divorce and marital distress for those who cohabited before having made a mutual commitment to marry. Specifically, our first hypothesis was that at the first assessment (before random assignment to the intervention or control group), married couples with a history of pre-commitment cohabitation would show “a pre-commitment cohabitation effect”; that is, they would have lower marital satisfaction, lower dedication, and more negative communication than those who cohabited only after clarifying a commitment to marriage or who did not cohabit at all before marriage. Second, we hypothesized that there would be an interaction between intervention status and cohabitation history such that the pre-commitment cohabitation effect would be apparent only in the control group after intervention and not in the PREP group. Third, we hypothesized that pre-commitment cohabitation would be associated with a higher risk for divorce in the control group, but not in the PREP group.

We tested these hypotheses using a sample of U.S. Army couples who were randomly assigned to PREP or to a no-treatment condition. Prior publications with this sample have demonstrated that PREP is associated with increases in some aspects of marital quality in the short-term (Allen, Stanley, Rhoades, Markman, & Loew, 2011) and with a decreased risk for divorce up to two years post intervention (Stanley et al., 2014).

If receiving relationship education can mitigate the risk of pre-commitment cohabitation, there may be policy and practice implications, as well as implications for whether social scientists consider premarital cohabitation to be a static or dynamic risk factor for poor marital outcomes. Because cohabitation obviously occurs before marriage, practitioners and policy makers concerned with improving marital quality and stability may consider it an unchangeable or static risk. Although it is true that we cannot change the past, demonstrating that relationship education can alter the dynamics associated with pre-commitment cohabitation is important because it may suggest options for intervention that may not have been considered before.

Method

Participants

This sample included 662 Army couples. The average age at the baseline (pre-random assignment) assessment was 28.5 years (SD = 5.9) for husbands and 27.7 years (SD = 6.2) for wives. Wives were 71% White (non-Hispanic/Latina), 11% Hispanic/Latina, 10% African American, 2% Native American/Alaska Native, 1% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 1% Asian; 5% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Husbands were 69% White (non-Hispanic/Latino), 12% Hispanic/Latino, 11% African American, 1% Native American/Alaska Native, 1% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 1% Asian; 5% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Almost all husbands (97.4%) were Active Duty Army (2.3% were in the study due to their wives being Active Duty), whereas almost all wives (91.7%) were civilian spouses of Active Duty husbands (8.0% of wives were Active Duty Army or Reserves). Husbands’ median income was between $30,000 and $39,999 a year; wives’ median income was under $10,000 a year. High school or an equivalency degree was the median highest degree (endorsed by 69% of husbands and 55% of wives). At the baseline assessment, couples had been married an average of 4.9 years, and 74% reported at least one child living with them at least part-time.

Procedures

Complete details of the procedures for the test of the interventions are available in prior publications (e.g., Stanley, Allen, Markman, Rhoades, & Prentice, 2010); an overview is provided here. Two sites were used: Site 1 included 478 couples and Site 2 included 184 couples. Although there were some socio-demographic differences between the sites (i.e., on length of marriage, age, rank, income, and deployment history), there were no significant differences between the sites on indices of marital quality at the baseline assessment (Allen et al., 2011).

To be eligible for the study, couples had to be married, with both partners age 18 or over, fluent in English, and with at least one active-duty spouse in the Army. Couples could not have already participated in PREP and had to be willing to be randomly assigned to either the intervention or the no-treatment control group, which can be considered treatment-as-usual. Recruitment was conducted via brochures, media stories, posters, and referrals from chaplains. All procedures were approved by a university Institutional Review Board.

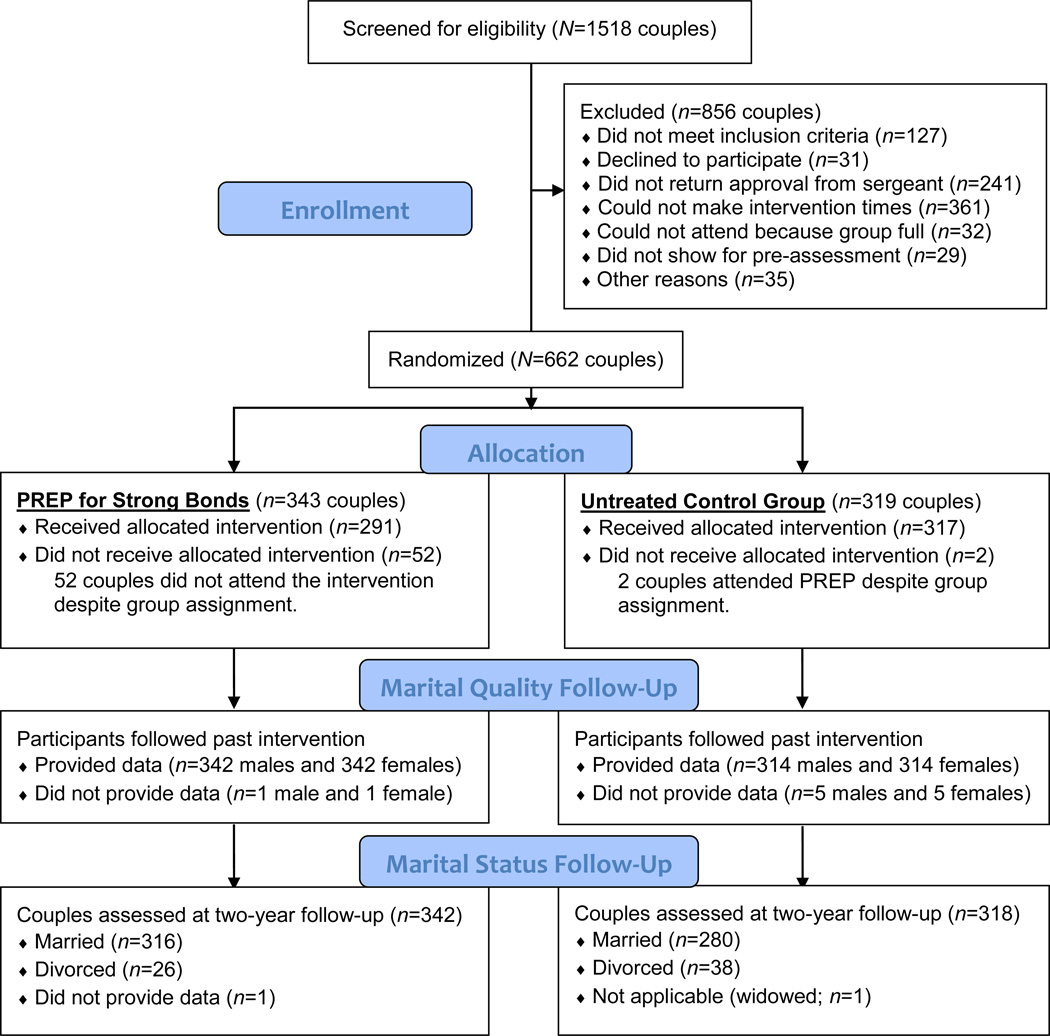

Prior to random assignment, spouses completed the baseline questionnaires separately (“pre”); 343 couples were then randomly assigned to the intervention and 319 were assigned to the control group (see CONSORT table). As described by Stanley et al. (2014), there were 53 cohorts randomly assigned and 27 iterations of the intervention. After each iteration’s intervention was complete, spouses completed another set of measures separately (“post”). Approximately every six months after post, participants whose marriages remained intact completed online measures. These follow-up assessments took approximately one hour to complete and each spouse was paid $50 to $70 depending on the time point. The current analyses are based on a subset of measures collected at pre and post and the subsequent four follow-up assessments. The fourth follow-up assessment was completed two years after post.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Report Trials (CONSORT) Table

Intervention and Attendance

The intervention was a version of PREP (Markman et al., 2010) adapted for Army couples and delivered by Army chaplains to groups of Army couples in a workshop format (Stanley, Markman, Jenkins, & Blumberg, 2006). The workshop consisted of two parts: a one-day on-post training followed by a weekend retreat at an off-post hotel, totaling approximately 14.4 hours of training. Intervention modules included communication and problem solving skills training, negative affect management, insights into relationship dynamics, emotional support, stress and relaxation, principles of commitment, fun and friendship, forgiveness, sensuality and sexuality, expectations, core beliefs, and deployment/reintegration issues.

All analyses use an intent-to-treat design. That is, those assigned to the intervention group are analyzed as part of that group regardless of whether couples attended the workshops. At Site 1, 60% attended all, 23% attended part (e.g., either the duty day of training or the weekend retreat, but not both), and 17% attended none of the intervention. At Site 2, 54% attended all, 35% attended part, and 11% attended none of the intervention. Two couples assigned to the control group attended the intervention at Site 1.

Measures

Premarital cohabitation history

At pre, all participants were asked “Did you live together (that is, share the same address) before you got married?” and “If yes, had the two of you already made a specific commitment to marry when you first began living together?” Partners who agreed that they had not cohabited before marriage or who said that they had made a specific commitment to marry when first living together were coded 1 for having made a mutual commitment to marry before cohabiting (58.6%). Those who agreed that they had not made a specific commitment to marry when they began living together or who gave discrepant answers were coded 0 for not having made a mutual commitment to marry before cohabiting (41.4%; “pre-commitment cohabitation”).

Marital satisfaction

The Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (Schumm et al., 1986) was used to measure marital satisfaction at all waves. It includes three items rated on a 1 to 7 scale and has strong reliability and validity (Schumm et al., 1986). At pre, the average score was 5.67 (SD = 1.27); internal consistency (α) was .94.

Dedication

Dedication was assessed with 5 items from the Dedication subscale of the Revised Commitment Inventory, a measure shown to be reliable and valid (Owen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2011; Stanley & Markman, 1992), including in brief form (Cui & Fincham, 2010; Rhoades et al., 2009). Each item such as “My relationship with my spouse is more important to me than almost anything else in my life” was rated on a 1 to 7 scale. At pre, the average score was 6.57 (SD = 0.68); α was .84.

Negative communication

Negative communication was assessed with 4 items from the Communication Danger Signs Scale (Stanley & Markman, 1997). Short forms of this scale have been shown to be reliable and valid in other research (e.g., Allen et al., 2011; Rhoades et al., 2009). Each item (e.g., “My spouse criticizes or belittles my opinions, feelings, or desires”) was rated on a 1 to 3 scale. At the pre-intervention assessment, participants’ average score was 1.92 (SD = 0.53); α was .76.

Divorce

A couple was considered divorced if either spouse reported that they had obtained or filed for a divorce as of the two-year follow-up assessment. At Site 1, there were 54 divorces (11.3%) and 2 couples with missing data on divorce; one participant died (not combat-related) prior to the two-year time point and we could not ascertain divorce status at two years post-intervention for the other couple. At Site 2, there were 10 divorces (5.4%) and no missing data.

Results

To test the first hypothesis that those who did not have a mutual commitment to marry when they moved in together would have lower marital satisfaction, lower dedication, and more negative communication at pre than those with a mutual commitment, we ran 2 X 2 ANOVAs in which gender was a within-subject variable (i.e., the couple was the unit of analysis) and pre-commitment cohabitation history was a between-subjects variable (see Table 1). There were three outcome variables: marital satisfaction, dedication, and negative communication. (These measures were correlated |.36 | to |.61| with one another, M = |.52|.) There were no significant main effects of gender, nor any significant gender X pre-commitment cohabitation history interactions in any of these three ANOVAs. As hypothesized, for marital satisfaction and dedication, there were significant main effects of cohabitation history with those who had cohabited before a mutual commitment to marriage reporting lower marital satisfaction and lower dedication than those who cohabited only after marriage/after a specific mutual commitment to marriage at pre. The sizes of these differences were small. Contrary to our first hypothesis, there was not a significant main effect of pre-commitment cohabitation history for negative communication at pre. We also tested whether there were any group (PREP vs. control)×cohabitation history interactions at the pre-intervention assessment by including group as a factor in additional repeated-measures ANOVAs. There were no significant group X cohabitation history interactions for any of the dependent variables at pre (marital satisfaction: F(1, 653) = 0.06, p = .81, dedication: F(1, 650) = 0.13, p = .72, negative communication: F(1, 653) = 0.95, p = .33).

Table 1.

Differences in Indices of Marital Quality by Cohabitation History Before Intervention

| Variable | Pre-Commitment Cohabitation n = 274 M (SD) |

Cohabited only After Commitment or Marriage n = 388 M (SD) |

Effect Size | F-statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Satisfaction | 5.55 (1.24) | 5.75 (1.32) | 0.16 | F(1,655) = 5.14* |

| Dedication | 6.49 (0.77) | 6.61 (0.60) | 0.18 | F(1,652) = 9.33** |

| Negative Communication | 1.96 (0.54) | 1.90 (0.53) | −0.11 | F(1,655) = 1.84 |

Notes. Effect size = Cohen’s d.

p < .05,

p < .01.

The next hypothesis was that the pre-commitment cohabitation effect would be apparent only in the control group after the intervention phase of the project (see Table 2 for results). We tested for differences in terms of both level (i.e., the intercept) and the slope (i.e., changes over time in the dependent variable), using 4-level multilevel models and HLM 7.0 software (Raudenbush, Bryk, Fai, Congdon, & du Toit, 2011). This approach accounted for the nested nature of these data, as time was nested within individuals who were nested within couples who were nested within cohorts. The equation below demonstrates the analyses that were conducted separately for marital satisfaction, dedication, and negative communication. Pre levels of the dependent variable were controlled for and Time was measured in months since post and grand-mean centered so that it could be interpreted as the estimated level of the dependent variable at the mean number months of follow-up since post. The Cohabitation History and Intervention Group variables were also grand-mean centered to be consistent. For tests of key interactions (i.e., Cohabitation History X Intervention Group), we used one-tailed tests, as they were hypothesized and because interactions tend to be underpowered (McClelland & Judd, 1993). For all other analyses, we used two-tailed tests. We calculated effect sizes using: r = √[t2/(t2 + df)].1

| Level-1 (Time): | Marital Satisfactiontijk = π0ijk + π1ijk(Timetijk) + etijk |

| Level-2 (Individual): | π0ijk = β00jk + β01jk(Pre Satisfactionjk) + r0ijk |

| π1ijk = β10ijk + β11ijk(Pre Satisfactionjk) | |

| Level-3 (Couple): | β00jk = γ000k + γ001k(Cohabitation History) + u00j |

| β01jk = γ010k | |

| β10jk = γ100k + γ101k(Cohabitation History) | |

| β11jk = γ110k | |

| Level-4 (Cohort): | γ000k = δ0000 + δ0001(Intervention Groupk) + v000k |

| γ001k = δ0010 + δ0011(Intervention Groupk) | |

| γ010k = δ0100 | |

| γ100k = δ1000 + δ1001(Intervention Groupk) | |

| γ101k = δ1010 + δ1011(Intervention Groupk) | |

| γ110k = δ1100 |

Table 2.

Summary of Multilevel Modeling Analyses Examining Group by Cohabitation History Interactions

| Fixed Effects | Marital Satisfaction |

Dedication | Negative Communication |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Average Level | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.82*** | 0.32 | 2.04*** | 0.17 | 0.94*** | 0.12 |

| Group | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04+ | 0.02 |

| Cohabitation History | 0.94 | 0.62 | −0.17 | 0.05 | −0.24 | 0.22 |

| Cohabitation History X Groupa | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Pre-assessment Quality | 0.61*** | 0.02 | 0.66*** | 0.03 | 0.56*** | 0.02 |

| Change Over Time (Slope) | ||||||

| Intercept | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 |

| Group | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cohabitation History | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.03** | 0.01 |

| Cohabitation History X Groupa | 0.01* | 0.01 | 0.01+ | 0.00 | −0.01** | 0.00 |

| Pre-assessment Quality | −0.01*** | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01*** | 0.00 |

Notes.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001,

one-tailed tests were used for predicted interactions.

In support of the second hypothesis, the Cohabitation History X Intervention Group interaction was significant for the intercept for dedication. An analysis of simple effects indicated that for those in the control group, pre-commitment cohabitation was associated with lower estimated dedication at the midpoint of the two years following intervention (b = -0.18, p < .01, r = .14), but that there was no difference in dedication based on cohabitation history for those in the PREP group (b = 0.01, p = .80, r < .01). There was not a significant Cohabitation History X Intervention Group interaction for the slope of dedication.

There was not a significant Cohabitation History X Intervention Group interaction for the intercept for marital satisfaction, but there was a significant interaction effect for the slope. An analysis of simple effects indicated that for those in the control group, marital satisfaction declined more across the two years following post for those who cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry compared to those who did not (b = −0.012, p < .01, r = .19), but there was no such difference for those in the PREP group (b = −0.002, p = .72, r = .02).

There was not a significant Cohabitation History X Intervention Group interaction for the intercept for negative communication, but there was a significant interaction effect for the slope. An analysis of simple effects indicated that for those in the control group, negative communication increased more for those who cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry compared to those who did not (b = −0.005, p < .01, r = .18), but there was no such difference for those in the PREP group (b = -0.002, p = .32, r = .06).

Our third hypothesis was that having cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry would be associated with divorce in the control group, but not in the PREP group, and it was supported. A significant chi-square test in the control group showed that 18 out of 123 (14.6%) of those who cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry filed for divorce compared to 14 out of 186 (7.5%) of those who did not, χ2 (1, N = 309) = 4.03, p < .05. For the PREP group, there was not a significant difference in divorce by cohabitation history, with 11 out of 141 (7.8%) of those who cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry having filed for divorce compared to 14 out of 188 (7.4%) of those who did not, χ2 (1, N = 329) = 0.02, p = .90.

Discussion

The results of this study supported our general hypothesis that PREP would mitigate the risk of having cohabited before making a mutual commitment to marriage. We examined marital satisfaction, dedication, and negative communication as indices of marital quality. On two of the three indices, we found small, but significant differences before random assignment (which was about five years into marriage, on average) between those who had cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry and those who had not, supporting prior research that this specific type of premarital cohabitation is associated with marital distress and divorce (e.g., Rhoades et al., 2009; Stanley, Rhoades, et al., 2010). After the intervention phase of the study was complete, this cohabitation effect was only apparent in the control group and not in the PREP group. In the control group, there were differences in average levels of dedication based on cohabitation history and there was evidence that those who cohabited before a mutual commitment were declining more in marital satisfaction and increasing more in negative communication over the two-year period than those who cohabited only after a mutual commitment to marry. These findings may reflect that among those who cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry, PREP had a more immediate impact on dedication and a longer-term impact on satisfaction and negative communication. Further, two years after the intervention, there was an association between having cohabited before a mutual commitment to marriage and divorce in the control group, but not in the PREP group. Specifically, couples in the control group who cohabited before a mutual commitment to marry were twice as likely to divorce compared to those who cohabited only after a mutual commitment to marriage.

The association between having pre-commitment cohabitation history and marital quality are small, which is consistent with other work that examined couples several years into marriage (Rhoades et al., 2009). Some of the couples most at risk for lower marital quality likely divorced earlier on and therefore are not included in the marital quality analyses (for a discussion of this methodological challenge, see McConnell, Stuart, & Devaney, 2008).

Even though the effects are small, that we find these effects on more than one index of marital quality and on divorce is important. We chose variables that have been theorized and shown to be related to premarital cohabitation history in previous research (Kline et al., 2004; Stanley, Rhoades, et al., 2006; Stanley, Whitton, & Markman, 2004), and these findings demonstrate that relationship education may be particularly beneficial to couples who cohabited before they were committed to marriage in terms of their marital satisfaction, communication, dedication, and their risk for divorce. They add to a growing literature on different risk factors that may be associated with greater gains in prevention services (e.g., Allen, Rhoades, Stanley, Loew, & Markman, 2012; Amato, 2014; Halford & Bodenmann, 2013; Halford et al., 2001; Petch et al., 2012). If these kinds of findings were replicated in future work, they could be good news to couples who have what appear to be static risk factors for marital distress or divorce, as they suggest that relationship education may reduce such risks. In fact, static risk factors might be better thought of as inertial risk factors, as their sequelae are not impossible to change. That is, static factors seem to set in motion dynamics that may be ameliorated by intervention.

Limitations and Conclusion

This study’s findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, premarital cohabitation history was measured after marriage and, for some, long after they began cohabiting. There were some discrepancies between partners’ reports of their cohabitation histories and future research could improve measurement of cohabitation history by using an interview with both partners together and/or by documenting cohabitation at the time it happens. Second, couples had been married five years, on average, when they started this study, and this characteristic of the sample reflects a selection effect in that some of the couples most at risk for divorce would not have qualified for the study because they had already divorced. Future research should test these associations with a sample of more recently married couples as well as with a longer time horizon for measuring divorce. Third, this sample included only couples who were part of the U.S. Army. We cannot know if the findings generalize to civilian couples, as reasons for cohabitation and marriage may be different across civilian and military contexts.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study contributes new knowledge to both research on premarital cohabitation as well as research on relationship education for couples. The findings support the idea that relationship education curricula like PREP can mitigate the association between cohabitation before a commitment to marry and later marital distress and divorce.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD048780). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. Co-authors Scott Stanley and Howard Markman own a company, PREP, Inc., that distributes relationship education materials, including the curriculum examined in this study. Galena Rhoades receives royalties on some materials distributed by PREP, Inc., though not from the curriculum tested in this study

Footnotes

We did not have any hypotheses about gender differences, given that the broader literature has identified few gender differences in the way cohabitation is associated with marital quality/divorce or in how relationship education impacts relationship outcomes. Nevertheless, we tested whether Gender X Cohabitation History X Intervention Group interactions were significant for the intercepts (i.e., levels of satisfaction, dedication, or negative communication) or slopes (i.e., change over time in the above variables). There were no significant Gender X Cohabitation History X Intervention Group interactions, so we elected not to include gender as a factor in the analyses presented.

Contributor Information

Galena K. Rhoades, University of Denver

Scott M. Stanley, University of Denver

Howard J. Markman, University of Denver

Elizabeth S. Allen, University of Colorado Denver

References

- Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Loew B, Markman HJ. The effects of marriage education for Army couples with a history of infidelity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:26–35. doi: 10.1037/a0026742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ES, Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ, Loew BA. Marriage education in the Army: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy. 2011;10(4):309–326. doi: 10.1080/15332691.2011.613309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Does social and economic disadvantage moderate the effects of relationship education on unwed couples? An analysis of data from the 15-month Building Strong Families evaluation. Family Relations. 2014;63(3):343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard VL, Hawkins AJ, Baldwin SA, Fawcett EB. Investigating the effects of marriage and relationship education on couples' communication skills: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(2):203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0015211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Fincham FD. The differential effects of divorce and marital conflict on young adult romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:331–343. [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Bodenmann G. Effects of relationship education on maintenance of couple relationship satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(4):512–525. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Sanders MR, Behrens BC. Can skills training prevent relationship problems in at-risk couples? Four-year effects of a behavioral relationship education program. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(4):750. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose A, O’Leary DK, Moyer A. Does premarital cohabitation predict subsequent marital stability and marital quality? A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(1):105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kline GH, Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Olmos-Gallo PA, St. Peters M, Whitton SW, Prado LM. Timing is everything: Pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk for poor marital outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(2):311–318. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau J-P, Stanley SM, Olmos-Gallo A, Baucom B, Markman HJ. Community-based prevention of marital dysfunction: Multilevel modeling of a randomized effectiveness study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):933. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Cohen JA. Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74(2):377–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Renick MJ, Floyd FJ, Stanley SM, Clements M. Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: A 4- and 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(1):70. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Rhoades GK. Relationship education research: Current status and future directions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38(1):169–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Stanley SM, Blumberg SL. Fighting for your marriage. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell S, Stuart EA, Devaney B. The truncation-by-death problem: What to do in an experimental evaluation when the outcome is not always defined. Evaluation Review. 2008;32:157–186. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07309115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JJ, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. The Revised Commitment Inventory: Psychometrics and use with unmarried couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32:820–841. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10385788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petch JF, Halford WK, Creedy DK, Gamble J. A randomized controlled trial of a couple relationship and coparenting program (Couple CARE for Parents) for high- and low-risk new parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(4):662–673. doi: 10.1037/a0028781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Fai CY, Congdon R, du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. The pre-engagement cohabitation effect: A replication and extension of previous findings. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(1):107–111. doi: 10.1037/a0014358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm WR, Paff-Bergen LA, Hatch RC, Obiorah FC, Copeland JM, Meens LD, Bugaighis MA. Concurrent and discriminant validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1986;48(2):381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Allen ES, Markman HJ, Rhoades GK, Prentice DL. Decreasing divorce in U.S. Army couples: Results from a randomized controlled trial using PREP for Strong Bonds. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy. 2010;9(2):149–160. doi: 10.1080/15332691003694901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Marriage in the 90s: A nationwide random phone survey. Denver, CO: PREP; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Jenkins NH, Blumberg SLD. PREP for Strong Bonds leader's manual. Denver, CO: PREP Educational Products, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Prado LM, Olmos-Gallo PA, Tonelli L, St. Peters M, Whitton SW. Community-based premarital prevention: Clergy and lay leaders on the front lines. Family Relations. 2001;50(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Amato PR, Markman HJ, Johnson CA. The timing of cohabitation and engagement: Impact on first and second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(4):906. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Loew BA, Allen ES, Carter S, Osborne LJ, Markman HJ. A randomized controlled trial of relationship education in the U.S. Army: 2-year outcomes. Family Relations. 2014;63(4):482–495. doi: 10.1111/fare.12083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ. Sliding vs. deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations. 2006;55:499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Whitton SW, Markman HJ. Maybe I do: Interpersonal commitment and premarital or nonmarital cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25(4):496–519. [Google Scholar]