Abstract

Drugs that target DNA topoisomerase II, such as the epipodophyllotoxin etoposide, are a clinically important class of anticancer agents. A recently published X-ray structure of a ternary complex of etoposide, cleaved DNA and topoisomerase IIβ showed that the two intercalated etoposide molecules in the complex were separated by four DNA base pairs. Thus, using a structure-based design approach, a series of bis-epipodophyllotoxin etoposide analogs with piperazine-containing linkers was designed to simultaneously bind to these two sites. It was hypothesized that two-site binding would produce a more stable cleavage complex, and a more potent anticancer drug. The most potent bis-epipodophyllotoxin, which was 10-fold more growth inhibitory toward human erythroleukemic K562 cells than etoposide, contained a linker with eight methylene groups. All of the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins, in a variety of assays, showed strong evidence that they targeted topoisomerase II. COMPARE analysis of NCI 60-cell GI50 endpoint data was also consistent with these compounds targeting topoisomerase II.

Keywords: epipodophyllotoxin, topoisomerase II, etoposide, structure-based design, anticancer, DNA, COMPARE, K562 cells, molecular modeling, docking

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction1

Etoposide is a widely used anticancer drug and is a topoisomerase II poison/interfacial inhibitor that exerts its cytotoxicity through its ability to stabilize a covalent topoisomerase II-DNA cleavable complex intermediate which leads to double-strand DNA breaks that are toxic to the cell.1–4 The X-ray structure of two molecules of etoposide complexed to a cleaved DNA-topoisomerase IIβ ternary complex (PDB ID: 3QX3) has recently been determined.5–7 In this structure two etoposide molecules that intercalate into the cleaved DNA are separated by four base pairs. Unlike planar DNA intercalators that stack with two bases, the aglycone moiety of etoposide stacks only with a single +5 guanine base in a deformed DNA structure.6 It has been shown that etoposide is itself a weak DNA intercalator (dissociation constant 11 μM).8,9 The glycosidic moieties of the two bound etoposide molecules occupy spacious binding pockets in the protein. Consequently, compounds in which the glycosidic moiety of etoposide is modified (e.g., teniposide), or even replaced, retain excellent activity.10–14 This provided us an opportunity to substitute the glycosides with linkers of various sizes in order to optimize epipodophyllotoxin two-site binding. We recently used the DNA-topoisomerase IIβ ternary complex X-ray structure to carry out structure-based design of a series of potent epipodophyllotoxin-nitrogen-mustard hybrid compounds that were designed to covalently bind to topoisomerase II and DNA.14 The nitrogen-mustard functionalities were based on the clinically efficacious nitrogen mustards chlorambucil, bendamustine and melphalan. In previous studies we also described the synthesis and activity of photoaffinity etoposide probes.12,13

We also synthesized and tested a series of DNA-binding bisanthrapyrazole compounds15–17 that were designed to achieve bisintercalation separated by four DNA base pairs. These compounds displayed excellent cell growth inhibition, and were also strong topoisomerase IIα inhibitors. In principle, molecules that can interact with two binding sites on DNA, as opposed to a single binding site, should have a much stronger DNA interaction and a slower rate of dissociation. These effects are due to the bisintercalator occupying twice the number of DNA intercalation sites on the DNA. This potential for stronger DNA binding is based on a simple model in which the different intercalation sites contribute equally and independently to the free energy.18 Thus, by analogy, an etoposide analog that contains two epipodophyllotoxin moieties, separated by a linker of a length that allows bisintercalation into the two etoposide binding sites, should, in principle, result in a more stable and longer-lived cleavage complex, and consequently a more selective and cytotoxic etoposide analog.

Bis-epipodophyllotoxins with various sizes and types of linkers that link the two epipodophyllotoxin moieties through attachment to the E-ring pendant phenolic groups have been described and tested in vivo for antitumor activity.19 Epipodophyllotoxin-acridine hybrids with six and eight methylene linkers were shown to target topoisomerase II, and to have good cell growth inhibitory activity.20 The synthesis and testing of bis-epipodophyllotoxins with linkers of various sizes and types that had triplex-forming oligonucleotides attached, in order to increase their DNA sequence specificity, have been shown to induce topoisomerase IIα DNA cleavage.21,22 Several tubulin-targeted bis-podophyllotoxin compounds with linkers of various sizes and types displayed only moderate cell growth inhibitory activity, but were not tested for their ability to target topoisomerase II.23

Guided by molecular modeling and docking into the two etoposide binding sites in the DNA-topoisomerase IIβ ternary complex X-ray structure,5–7 we designed and synthesized a series of mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxin compounds by substituting the glycosidic moieties with linkers of varying length in order to determine the minimum and the optimum linker chain length to optimize topoisomerase II poisoning and cell growth inhibition. Two piperazines were included in the linker, both to increase solubility, and to exploit the polyamine transport system, as has been done with the polyamine-linked etoposide analog F14512.10 All of the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins, in a variety of assays, showed strong evidence of targeting topoisomerase II. The most potent bis-epipodophyllotoxin of the series 7c (Scheme 1) had an IC50 value towards K562 cells that was 10-fold more potent than etoposide. A second bis-epipodophyllotoxin compound 7d tested in the NCI-60 cell screen (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov) had a mean GI50 value over all cell lines that was 25-fold more potent than etoposide.

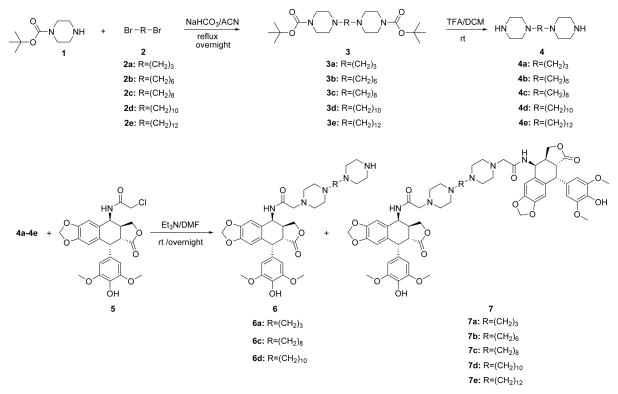

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of piperazine-linked mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins and their precursors.

2. Chemistry

The piperazine-linked mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins were synthesized as shown in Scheme 1. The Ritter reaction of chloroacetonitrile with 4′-O-demethylepipodophyllotoxin (AvaChem, San Antonio, TX) was carried out24 to make the 4-chloroacetamido-4-deoxy-4′-demethylepipodophyllotoxin (5) in excellent yield as we and others have reported.14,25 The bis-piperazine intermediates 4a – 4e were prepared in 80 – 90% yields via the reaction of 1-Boc-piperazine 1 with dibromoalkanes 2a – 2e followed by deprotection of the t-Boc group under acidic conditions as we and others have reported.14,15,26 Bispiperazines 4a – 4e were then reacted with 5 (1 or 2 equivalents) in the presence of triethylamine to afford mono- (6a, 6c, 6d) and bis-epipodophyllotoxins (7a – 7e) in moderate to good yields. The reaction of an equimolar amount of 5 and 4 gave both mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins, but when two equivalents of 5 and one equivalent of 4 were reacted together, the reaction yielded essentially bis-epipodophyllotoxins.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Cell growth inhibitory effects of mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins on human leukemia K562 cells and K/VP.5 cells with a decreased level of topoisomerase IIα

The cell growth inhibitory effects of the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins on human leukemia K562 cells and etoposide-resistant K/VP.5 cells27,28 are compared to etoposide in Table 1. All the bis-epipodophyllotoxins displayed sub-micromolar IC50 values, with the most potent 7c being 10-fold more potent than etoposide. The IC50 values systematically decreased with an increase in methylene linker length and reached a minimum with compound 7c which contained eight methylenes. The IC50 values then coordinately increased when the linker length was increased to ten and twelve methylenes (compounds 7d and 7e, respectively). These results suggested that an optimum chain length was in the order of eight methylene groups, and thus may be the optimum chain length needed for the bis-epipodophyllotoxins to achieve bisintercalation in the DNA within the topoisomerase IIβ-DNA ternary structure. Increasing linker length also enhanced the cell growth inhibitory potency of the mono-epipodophyllotoxins that contained two piperazine moieties separated by either three, eight or ten methylene linkers (6a, 6c and 6d, respectively). The most potent 6d was 6-fold more potent than etoposide. The fact that the mono compounds were so active may be because they are polyamines that were taken up by the polyamine transport system as has been proposed for the polyamine-linked etoposide analog F14512.10

Table 1.

Comparison of the cell growth inhibitory effects of mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins and etoposide towards K562 cells and etoposide-resistant K/VP.5 cells

| Compound | linker sizea | K562 IC50 (μM) | K/VP.5 IC50 (μM) | RRb | mean NCI-60 cell GI50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6a | 3 | 1.27 | 13.3 | 10.5 | ND |

| 6c | 8 | 0.103 | 0.556 | 5.4 | ND |

| 6d | 10 | 0.026 | 0.156 | 6.0 | ND |

| 7a | 3 | 0.525 | 7.5 | 14.2 | NDc |

| 7b | 6 | 0.041 | 0.88 | 21.5 | 3.7 |

| 7c | 8 | 0.016 | 0.115 | 7.4 | ND |

| 7d | 10 | 0.044 | 0.114 | 2.6 | 0.47 |

| 7e | 12 | 0.067 | 0.549 | 8.2 | ND |

| Etoposided | - | 0.163 | 2.50 | 15.4 | 12d |

Number of methylene groups linking the two piperazine groups.

RR is relative resistance (K/VP.5 IC50) K562 IC50). The K562 and K/VP.5 IC50 values are averages from experiments carried out on two separate days.

1-dose NCI-60 data for this compound is given in Supplemental Figure 3

NCI mean GI50 data from 38 experiments (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/compare).

ND is not determined.

Cancer cells can acquire resistance to topoisomerase II poisons by lowering their level and/or activity of topoisomerase II.29 We have previously used14,30 a clonal K562 cell line selected for resistance to etoposide as a screen to determine the ability of compounds to act as topoisomerase II poisons. The etoposide-selected K/VP.5 cells were previously determined to be 26-fold resistant to etoposide, and to contain reduced levels of both topoisomerase IIα(6-fold) and topoisomerase IIβ(3-fold).27,28 In addition, these cells are cross-resistant to other known topoisomerase II poisons, but are not cross-resistant to camptothecin and other nontopoisomerase IIα targeted drugs.28 Reduced topoisomerase II in the cell translates to fewer DNA strand breaks produced by topoisomerase II poisons and less cytotoxicity. As shown in Table 1, etoposide and compounds 6a, 7a and 7b were similar in their cross-resistance to K/VP.5 cells (10.5- to 21.5-fold cross-resistant). The other mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins were generally less cross-resistant (2.6- to 8.2-fold). The universal cross-resistant pattern for these newly synthesized compounds strongly suggests targeting of topoisomerase II.

3.2. Evaluation of cell growth inhibitory effects of the compounds in the NCI-60 human tumor cell line screen

Compounds 7a, 7b and 7d were accepted for testing in the NCI-60 cell screen by the National Cancer Institute (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov). These results allowed us to identify which tumor cell types were the most sensitive to these compounds and to carry out NCI COMPARE analyses (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/compare) to determine what other anticancer and cytotoxic drugs the bis-epipodophyllotoxins had similar tumor cell growth inhibition profiles, and thus to identify mechanisms by which the bis-epipodophyllotoxins exerted their activity. The NCI-60 cell 5-dose testing mean GI50 values for compounds 7b and 7d are given in Table 1 and the results for the individual cell lines are given in Supplemental Figures S1 and S2. The 1-dose (10 μM) testing results for 7a are given in Supplemental Figure S3. The leukemia cell lines were, as a group, the most sensitive to the two compounds tested, with GI50 values in the sub-micromolar range. Compounds 7a, 7b and 7d were the least growth inhibitory toward melanoma and ovarian cancers, with GI50 values in the low micromolar range. Compounds 7d and 7b that were subjected to 5-dose testing had mean GI50 values over all cell lines tested of 0.47 μM and 3.7 μM, respectively (Table 1). The mean GI50 value for etoposide over all cell lines tested was 12 μM (Table 1), Hence, compound 7d was 25-fold more potent than etoposide.

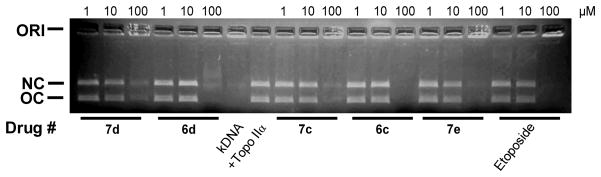

3.3 The mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins inhibited topoisomerase IIα decatenation activity, acted as topoisomerase IIα poisons and induced DNA double-strand breaks in cells

The torsional stress that occurs in DNA during replication and transcription and daughter strand separation during mitosis can be relieved by topoisomerase II. Topoisomerase II alters DNA topology by catalyzing the passing of an intact DNA double helix through a transient double-strand break made in a second helix.1–4 As shown in Figure 1 all of the compounds shown, including etoposide, required concentrations above 10 μM to inhibit the decatenation of kDNA by topoisomerase IIα. It should be noted that compounds 7c, 7d, and 7e showed some residual open circular DNA at 100 μM compared to that of etoposide, suggesting that these compounds were slightly less active than etoposide in the decatenation assay. Compounds 6a and 7a also showed comparable decatenation activity to that of etoposide (data not shown). The decatenation assay is a measure of the ability of compounds to inhibit the catalytic activity only, and is not a measure of whether they acted as topoisomerase II poisons.

Figure 1.

Effect of mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins, and etoposide positive controls, on the inhibition of the topoisomerase IIα-mediated decatenation activity of kDNA. The fluorescent images of the ethidium bromide-containing gel show that in the absence of added drug (lanes marked +Topo IIα) topoisomerase IIα decatenated kDNA to its open circular (OC) and nicked circular (NC) forms. Topoisomerase IIα was present in the reaction mixture for all lanes but lanes marked kDNA. ORI is the gel origin. The results were typical of experiments carried out on three different days.

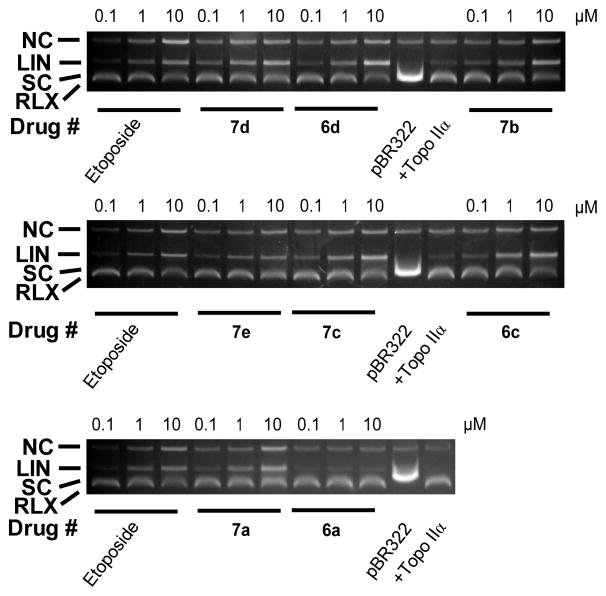

Stabilization of the covalent complex by a topoisomerase II-targeted drug can lead to double-strand DNA breaks that are toxic to the cell. Thus, DNA cleavage assay experiments14,30,31 were carried out to see whether the compounds stabilized the cleavable complex. As shown in Figure 2 the addition of the etoposide positive control to the reaction mixture containing topoisomerase IIα and supercoiled pBR322 DNA induced a concentration-dependent formation of linear pBR322 DNA. Linear DNA was identified by comparison with linear pBR322 DNA produced by action of the restriction enzyme HindIII acting on a single site on pBR322 DNA (not shown). As shown in Figure 2, all of the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins that were tested also induced a concentration-dependent formation of linear DNA, which indicated that they acted as topoisomerase IIα poisons. Based on the amount of linear DNA produced, all of the compounds, except mono-epipodophyllotoxin 6a, were as potent or more potent than etoposide. The three most cell growth inhibitory bis-epipodophyllotoxin compounds 7b, 7c and 7d induced topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage to linear DNA at a concentration as low as 0.1 μM (Figure 2). By comparison, etoposide at this concentration induced formation of linear DNA in amounts comparable to that observed for the control conditions (+Topo IIα alone).

Figure 2.

Concentration dependent effect of the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins and etoposide on the topoisomerase IIα-mediated relaxation and cleavage of supercoiled pBR322 plasmid DNA to produce linear DNA. These fluorescent images of ethidium bromide-stained gels show that topoisomerase IIα (+Topo IIα) converted supercoiled (SC) pBR322 DNA to relaxed (RLX) DNA. In this assay the relaxed DNA runs slightly ahead of the supercoiled DNA because the gel was run in the presence of ethidium bromide. Topoisomerase IIα was present in the reaction mixture in all but the lanes marked pBR322. The etoposide positive controls produced significant amounts of linear DNA (LIN). A small amount of nicked circular DNA (NC), which may arise from strand breakage during isolation, is normally present in pBR322 DNA. The results were typical of experiments carried out on three different days.

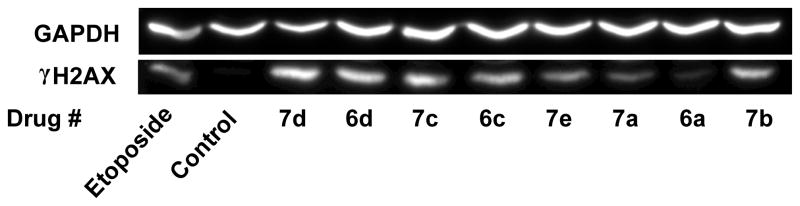

H2AX is a variant of an H2A core histone which becomes phosphorylated to produce γH2AX in the vicinity of double-strand DNA breaks upon treatment of cells with drugs or ionizing radiation.32 This phosphorylation becomes amplified over megabases of DNA surrounding the break, thus acting as a scaffold for the recruitment of key signaling and repair proteins, and, thus, is an accepted marker of double-strand breaks.32 Thus, in order to determine if the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins could induce double-strand breaks in intact K562 cells, the level of γH2AX was determined by Western blotting with etoposide as the positive control.31 Experiments carried out as we previously described,30,33 and shown in Figure 3, indicate that etoposide and all of the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxin compounds increased the levels of γH2AX in K562 cells. Compounds 7d, 6d, 7c, 6c and 7b induced even greater levels of γH2AX compared to etoposide. Compound 6a was less potent in the γH2AX assay and also in its ability to inhibit cell growth (Table 1). These results suggest that the compounds acted as topoisomerase II poisons in a cellular context to produce DNA double-strand breaks.

Figure 3.

Induction of double-strand DNA breaks in K562 cells by mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxin compounds as indicated by formation of γH2AX. K562 cells were treated with 25 μM of the compounds indicated for 4 h in growth medium, lysed and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and Western blotting. The blots were probed with antibodies to γH2AX and with GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) as a loading control and a chemiluminescent-inducing horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody.

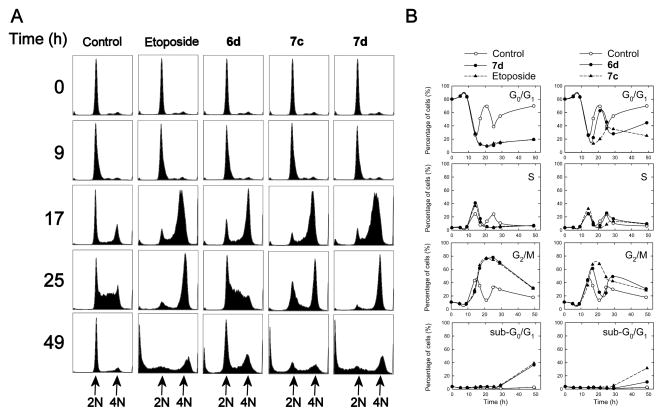

3.4 Cell cycle analysis and two-color flow cytometry and caspase 3/7 induction as markers of apoptosis

Cell cycle analysis was carried out on synchronized CHO cells as we previously described14,33 on the compounds indicated (Figure 4) in order to determine the mechanism by which these compounds might be acting. Drugs that act on topoisomerase IIα typically cause a block in G2/M.34 CHO cells (normal doubling time of 12 h) that were synchronized to G0/G1 through serum starvation were treated with 1 μM of the compounds indicated, or 10 μM etoposide for comparison. The cells were treated with a 10-fold lower concentration of the monoand bis-epipodophyllotoxins (1 μM) than for etoposide (10 μM) to compensate for the higher potency of these compounds compared to etoposide (Table 1). CHO cells were chosen for these experiments as they are easily and effectively synchronized by serum starvation. Subsequent to this starvation, serum repletion resulted in the DMSO vehicle-treated control cells advancing to G2/M by 14 h (Figures 4A and 4B). The control cells then went through several complete cell cycles as evidenced by the 12 h periodicity for peaks in the various cell cycle stages. By 49 h both 7d and 7c displayed a significant percentage of sub-G0/G1 cells comparable to that observed for etoposide, which was indicative of apoptosis, whereas mono-epipodophyllotoxin 6d had a sub-G0/G1 level about one-third that of etoposide. The percentage of sub-G0/G1 cells that was characteristic of induction of apoptosis was small in control-treated cells (< 2%). Treatment with etoposide caused a large block in G2/M by 21 h, which subsequently decreased at later times as the sub-G0/G1 population, indicative of late-stage apoptosis, increased to about 39% at 49 h. Both 7d and 7c displayed effects with a similar time-course compared to etoposide; a prolonged G2/M block followed by increased sub-G0/G1 levels. Compound 6d exhibited a more rapid escape from the G2/M block compared to 7c and 7d. The large G2/M blocks observed were typical of agents such as etoposide that target topoisomerase II.34 Hence, these results again are consistent with the compounds tested acting as topoisomerase II poisons.

Figure 4.

Cell cycle effects of mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins treatment of synchronized CHO cells. CHO cells that had been synchronized in G0/G1 through serum starvation were repleted with serum and were treated with the DMSO vehicle, or with either 10 μM etoposide or 1 μM of the compound indicated, directly after repletion and allowed to grow for the times indicated, after which they were subjected to cell cycle analysis of their propidium iodide-stained DNA. In (A) the cell counts are displayed on the vertical axis, and the DNA content is plotted on the horizontal axis. As shown in the top plots a high percentage of the serum starved cells were initially present in G0/G1. In (B) the percentage of the cells in the sub-G0/G1, G0/G1, S and G2/M phases is plotted as a function of time for each of the compounds indicated. The solid lines are least-squares calculated spline fits to the data. After serum repletion the percentage of control cells in each phase varied periodically as the cells progressed through several cell cycles.

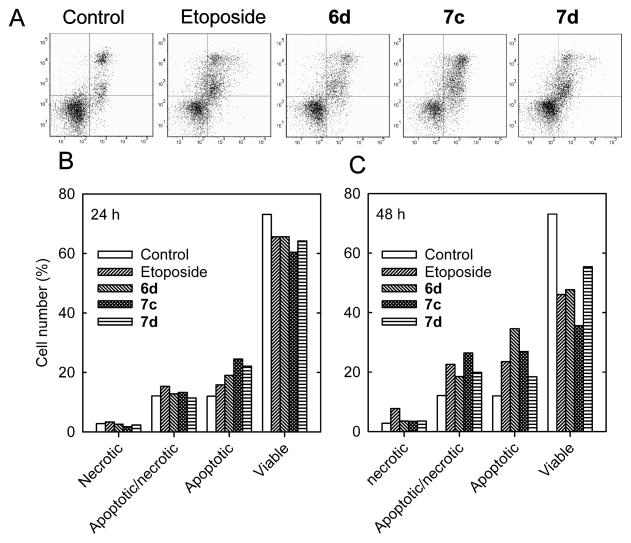

Early in the apoptotic process translocation of the phospholipid phosphatidylserine occurs from the inner to the external plasma membrane of cells.35 Fluorescent annexin V-FITC, which strongly binds phosphatidylserine on cells in the early stage of apoptosis, was used to identify apoptotic and apoptotic/necrotic cells by two-color flow cytometry, as we previously described.14,33 Annexin V-FITC stained K562 cells in both the lower and upper right quadrants of Figure 5A were considered to be apoptotic. When used in combination with propidium iodide, which binds DNA, a measure of cells that are necrotic may be obtained since necrotic cell membranes are permeable to propidium iodide. Thus, cells in the lower right quadrant were apoptotic-only and those in the upper right quadrant were apoptotic/necrotic. As shown in Figure 5B and 5C treatment of K562 cells for 24 h and 48 h with 1 μM of compounds 6d, 7c, 7d, and 10 μM etoposide all progressively reduced the proportion of viable cells, and increased the proportion of both apoptotic and apoptotic/necrotic cells. All the compounds tested were similarly, or more effective, than etoposide in inducing apoptosis, even though the compounds were tested at a 10-fold lower concentration.

Figure 5.

Treatment of K562 cells with the compounds indicated, or the etoposide positive control, induced apoptosis as determined by annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide two-color fluorescence flow cytometry. (A) Two-color flow cytometry scatter plots at 48 h for vehicle-treated control K562 cells, and cells treated with 1 μM of mono- or bis-epipodophyllotoxins or 10 μM of the etoposide positive control as indicated. Plots of the changes in the relative number of K562 cells that were classified as necrotic, apoptotic/necrotic, apoptotic or viable 24 h (B) or 48 h (C) after treatment are as indicated.

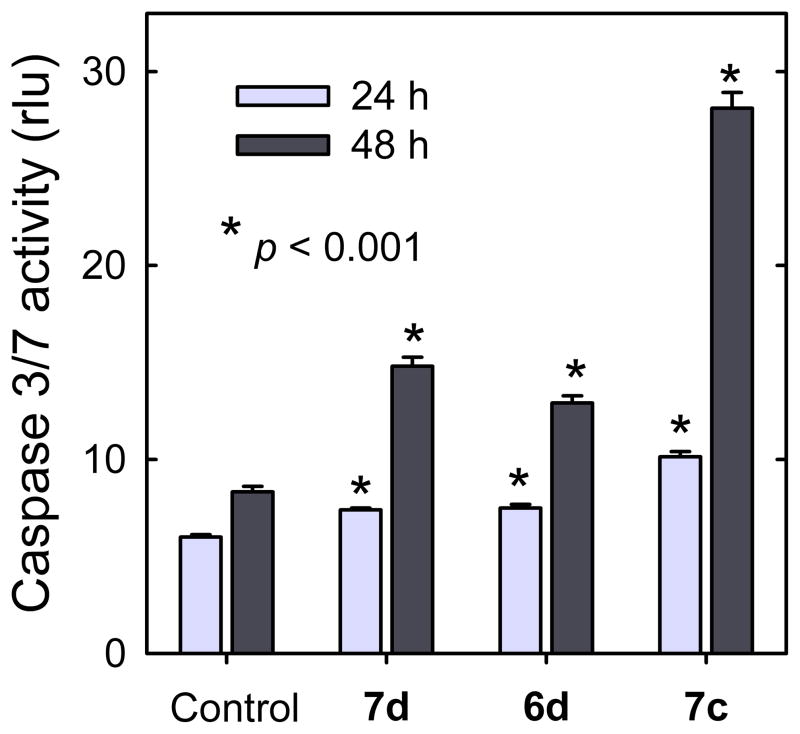

The cell cycle results (Figure 4) and the annexin V results (Figure 5) both indicated that mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins were able to induce apoptosis. Further confirmation of apoptosis induction was established by observation of caspase 3/7 activity, as we previously described,36 in the presence of 1 ΦM 6d, 7c and 7d (Figure 6). Treatment with these compounds resulted in a time dependent increase in caspase 3/7 activity compared to vehicle-treated controls, which was highly statistically significant (unpaired t-test) for all these agents (p < 0.001). These results are consistent with both the cell cycle results (Figure 4) and the annexin V results of Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Effect of the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins on induction of apoptosis in K562 cells. Treatment of K562 cells with 1 μM 7d, 6d or 7c, significantly, and progressively, increased caspase 3/7 activity relative to untreated controls. The results are averages (∀ SE) of four wells (eight for the control). Significance relative to the untreated controls: *p < 0.001. rlu is relative luminescent units. The results are typical of experiments carried out on two different days.

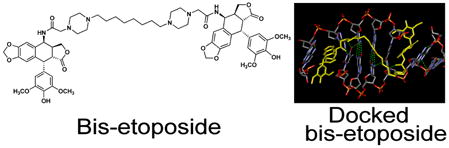

3.5 Docking of bis-epipodophyllotoxins into the two etoposide binding sites of the etoposide-DNA-topoisomerase IIβ ternary complex

It has been shown in the topoisomerase IIβ-DNA ternary X-ray structure, in which two molecules of etoposide are complexed to cleaved DNA and topoisomerase IIβ, that the glycosidic moiety of etoposide faces the DNA major groove, and occupies a spacious binding pocket in the protein with few protein interactions. The X-ray structure of the etoposide-topoisomerase IIβ-DNA complex was used in the docking studies because the corresponding topoisomerase IIα structure has not yet been published. There is, however, a high degree of homology (~78%) in the catalytic domains of topoisomerase IIα and topoisomerase IIβ.37 Thus, docking into the ternary topoisomerase IIβ structure5–7 should be a good proxy for the ternary topoisomerase IIα structure.

An examination of the topoisomerase IIβ ternary complex5–7 showed that the pendant E-ring phenolic group of etoposide interacted significantly with the protein, and thus would not be a suitable attachment point for constructing a bis-epipodophyllotoxin. In fact, bisepipodophyllotoxin compounds that linked two epipodophyllotoxin moieties through attachment to the pendant phenolic hydroxyl groups exhibited poor antitumor activity.19 However, the presence of the two spacious glycosidic binding pockets in the X-ray structure suggested that two epipodophyllotoxins could be linked together through a suitable linker that traversed the DNA major groove at the glycosidic attachment end of the epipodophyllotoxin. Thus, docking of proposed bis-epipodophyllotoxins was carried out into the X-ray structure. The results of the docking of 7d are shown in Figure 7. The X-ray-determined pose of the two etoposide molecules are shown in a yellow ball-and-stick representation in Figure 7B. In the highest scoring pose (shown in stick representation in atom colors), the piperazine linker is fully extended into the protein pocket normally occupied by the two glycosidic moieties, and the methylene linker occupies the major groove. The polycyclic and pendant phenolic moieties of this pose show a high degree of overlap with that of the X-ray structures of the bound etoposide molecules. For bis-epipodophyllotoxins with six or fewer methylene linkers (Scheme 1), no reasonable docking poses were found in which both epipodophyllotoxin moieties were simultaneously docked into both etoposide binding sites. These results suggested that the linkers in these bis-epipodophyllotoxins were not long enough to enable simultaneous docking into the two etoposide binding sites. It is, however, notable that 7b, which has a linker number of six, was more potent than etoposide; a result suggesting that this compound may form a more flexible complex in a cellular context, compared to that indicated in the fixed X-ray structure.

Figure 7.

Docking of bis-epipodophyllotoxin 7d into the two etoposide binding sites of the X-ray structure of two etoposide molecules complexed to cleaved DNA and topoisomerase IIβ. (A) Structure of etoposide. The three atoms marked with asterisks on the epipodophyllotoxin moiety of etoposide were used in setting the distance constraints. (B) Docking pose of compound 7d in the X-ray structure. The docked structure shown is the highest scoring pose of 7d (stick representation in atom colors) docked into the two etoposide binding sites of the X-ray structure. For clarity DNA is shown in a ladder representation and the protein is shown as a gray semi-transparent surface. The X-ray structure of the two etoposide molecules bound to the PDB ID: 3QX3 structure are shown in a yellow ball-and-stick structure. The H-atoms of the two bound etoposide molecules and of 7d displayed are not shown for clarity. In the docked pose of 7d the piperazine linker occupies the major groove. (C) View of 7d and DNA from the major groove side with the protein surface removed. 7d is shown here in yellow stick representation. The green broken lines are H-bonds.

3.6 COMPARE analysis of NCI-60 cell data

With 7b and 7d as seeds, both public and our private data (Supplementary Figures S1 – S3) were used in an NCI COMPARE analysis (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/compare) of the NCI-60 cell GI50 endpoint data. We previously used COMPARE analysis of the NCI-60 cell data to identify compounds that act through common mechanisms.14,33 COMPARE analysis is based on the assumption that compounds with a common mechanism of action will show a similar profile of log(GI50) values, as identified by significant correlation coefficients r. Thus, compounds 7b and 7d were submitted for COMPARE analysis using the NCI Marketed Drugs GI50 target set. For compound 7b, the five most highly correlated compounds were all well known topoisomerase II targeted drugs, and included, in order, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, the epipodophyllotoxin derivative teniposide and epirubicin, with r values ranging from 0.76 to 0.67, respectively. For compound 7d the most highly correlated compounds in this target set were also all well known topoisomerase II targeted drugs and included, in order, valrubicin, daunorubicin, teniposide, mitoxantrone and doxorubicin with r values ranging from 0.81 to 0.73, respectively. When etoposide itself was used as a seed, compounds 7b and 7d gave COMPARE correlation r values of 0.62 and 0.68, respectively. A COMPARE cross-correlation r value of 0.76 was found between 7b and 7d, which is expected since they are close analogs of one other. The 1-dose (at 10 μM) percent growth inhibition data for 7a was also highly correlated with 7b and 7d with r values of 0.80 and 0.70, respectively, which indicated that these compounds all shared a common target.

4. Conclusions

Five bis-epipodophyllotoxin compounds were designed using molecular modeling and docking into an X-ray structure of the topoisomerase IIβ-DNA-etoposide ternary complex.5–7 Results are also reported for three structurally similar bis-piperazine mono-epipodophyllotoxin analogs with varying methylene linker domains. The bis-epipodophyllotoxins that were designed through docking into the X-ray structure, and tested for their ability to inhibit cell growth and target topoisomerase II, contained two piperazine moieties separated by differing numbers of methylene groups. This was done in order to determine both the minimum and the optimum linker chain length in order to optimize cell growth inhibition and topoisomerase II poisoning. The most potent compound 7c, which contained a linker with eight methylene groups, had an IC50 toward K562 cells 10-fold lower than etoposide.

The mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxin compounds showed strong evidence that they targeted topoisomerase II. This was evidenced not only by their strong activities in the DNA cleavage assay (Figure 2), but also by the fact that they were cross-resistant toward etoposide-resistant K/VP.5 cells containing reduced levels of topoisomerase II (Table 1). Moreover, the ability of these compounds to induce DNA double strand breaks in the cellular γH2AX assays (Figure 3) and induce G2/M blocks in the cell cycle analyses were also characteristics of topoisomerase II-targeted drugs (Figure 4). The mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins tested were either as effective, or more effective, than etoposide in inducing apoptosis in cells (Figure 5). NCI COMPARE analyses of NCI 60-cell GI50 endpoint data showed that the bis-epipodophyllotoxin compounds correlated most highly with other well known topoisomerase II poisons. These and our other results confirmed that the mono- and bis-epipodophyllotoxins inhibited tumor cell growth by targeting topoisomerase II.

There is no direct experimental evidence that the bis-epipodophyllotoxins simultaneously bound to both etoposide binding sites in the topoisomerase II ternary complex. The docking results suggested that only bis-epipodophyllotoxins with eight or more methylene linkers (7c, 7d and 7e) are capable of achieving a bisintercalation binding mode. Continuing studies will focus on characterizing the relative selectivity of these compounds toward topoisomerase IIα and topoisomerase IIβ, and their cellular pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.

5. Experimental

5.1 Chemistry

1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at 300 K in 5 mm NMR tubes on a Bruker Avance 300 or 500 MHz NMR spectrometer, as indicated, operating at 300.13 MHz for 1H NMR and 75.5 MHz (or 125 MHz as indicated) for 13C NMR, respectively, in CDCl3. Chemical shifts are given in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane in the case of the 1H NMR spectra, and to the central line of CDCl3 (δ 77.0) for the 13C NMR spectra. Melting points were taken on a Gallenkamp (Loughborough, England) melting point apparatus and were uncorrected. The high resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were run on Bruker microTOF Focus mass spectrometer (Fremont, CA) using electron spray ionization (ESI). TLC was performed on plastic-backed plates bearing 200 μm silica gel 60 F254 (Silicycle, Quebec City, Canada). Compounds were visualized by quenching of fluorescence by UV light (254 nm) where applicable. The reaction conditions were not optimized for reaction yields. Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals were from Aldrich (Oakville, Canada) and were used as received.

Epipodophyllotoxin 5 (1 or 2 equivalents) was reacted overnight with the corresponding bispiperazines 4a – 4e (1 equivalent) in dimethylformamide in the presence of triethylamine (3 equivalents) at room temperature. After completion of reaction as determined by TLC, the mixture was quenched with water and extracted into dichloromethane. The combined extract was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum to give the crude product. Final purification was done by column chromatography (silica gel) using dichloromethane/methanol/30% ammonium hydroxide (85:10:5 v/v/v) as an eluant. All products were colorless solids except for 6a which was an oil.

5.1.1 N-[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]-1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]-2-{4-[3-(piperazin-1-yl)propyl]piperazin-1-yl}acetamide (6a)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 7.26 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.01 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 2H), 5.25 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 4.7 Hz,1H), 4.46 (t, J = 7.9, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (t, J = 7.9,0.7 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (s, 6H), 3.10 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 3.02 (m, 1H), 2.64-2.28 (m, 10H), 1.66 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 174.2, 170.1, 147.9, 147.2, 146.8, 134.4, 132.2, 129.8, 129.1, 109.7, 108.4, 108.0, 101.2, 68.6, 61.1, 56.1, 55.8, 53.1, 52.5, 50.0, 47.2, 43.5, 43.3, 41.4, 36.9, 23.7; HRMS (ESI) for C34H46N5O8 m/z (M+H)+: calcd 652.3341, obsd 652.3329; viscous oil; yield: 28%.

5.1.2 2-(4-{3-[4-({[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1(9),2,7-trien-10-yl]carbamoyl}methyl)piperazin-1-yl]propyl}piperazin-1-yl)-N-[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]acetamide (7a)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 7.25 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (s, 1H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.01 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 2H), 5.47 (bs, 1H), 5.25 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (t, J = 7.8, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (s, 6H), 3.10 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 3.02 (m, 1H), 2.84 (dd, J = 4.8, Hz, 1H), 2.64-2.28 (m, 10H), 1.66 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 174.3, 170.5, 148.3, 147.6, 146.6, 134.2, 132.5, 130.1, 129.0, 110.2, 108.5, 107.9, 101.6, 69.0, 61.3, 56.4, 53.6, 47.6, 43.6, 41.9, 37.2, 24.3; HRMS (ESI) for C57H67N6O16 m/z (M)+: calcd 1091.4608, obsd 1091.4626; mp: 248–252 °C; yield: 42%.

5.1.3 2-(4-{6-[4-({[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1(9),2,7-trien-10-yl]carbamoyl}methyl)piperazin-1-yl]hexyl}piperazin-1-yl)-N-[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]acetamide (7b)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 8.25 (bs, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (s, 1H), 6.54 (s, 1H), 6.24 (s, 2H), 5.99 (s, 2H), 5.20 (m, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.72-3.63 (m, 8H), 3.08-2.87 (m, 4H), 2.45-2.28 (m, 10H), 1.40-1.20 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ 174.5, 169.3, 147.1, 146.5, 134.6, 132.3, 130.2, 130.1, 109.4, 108.7, 108.4, 101.1, 68.3, 61.0, 57.6, 55.9, 53.6, 52.4, 46.4, 42.8, 40.7, 36.5, 26.8; HRMS (ESI) for C60H73N6O16 m/z (M+H)+: calcd 1133.5078, obsd 1133.5076; mp: 210–214 °C; yield: 62%.

5.1.4 N-[(10S,11S,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]-2-{4-[8-(piperazin-1-yl)octyl]piperazin-1-yl}acetamide (6c)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 7.28 (s, 2H), 6.75 (s, 1H), 6.59 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.01 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 5.26 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (t, J = 7.8, 8.2 Hz,1H), 3.89-3.75 (m, 7H), 3.12-2.63 (m, 8H), 2.58-2.14 (m, 16H), 1.44-1.28 (m, 12H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 174.3, 170.6, 148.3, 147.6, 146.7, 134.4, 132.5, 130.0, 129.1, 110.2, 108.5, 107.9, 101.6, 69.0, 61.3, 59.4, 58.5, 56.4, 54.4, 53.7, 52.9, 47.5, 45.9, 43.6, 42.0, 37.2, 29.4, 27.5, 26.8; HRMS (ESI) for C39H56N5O8 m/z (M+H)+: calcd 722.4123, obsd 722.4127; mp: 102–105 °C; yield: 32%.

5.1.5 2-(4-{8-[4-({[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1(9),2,7-trien-10-yl]carbamoyl}methyl)piperazin-1-yl]octyl}piperazin-1-yl)-N-[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]acetamide (7c)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 7.30 (s, 1H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.01 (d, J = 1.71 Hz, 2H), 5.49 (bs, 1H), 5.24 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (t, J = 7.4, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.87-3.75 (m, 7H), 3.18-2.95 (m, 3H), 2.87-2.77 (dd, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H) 2.65-2.25 (m, 10H), 1.79-1.30 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 174.3, 170.5, 148.3, 147.6, 146.5, 134.2, 132.5, 130.1, 129.1, 110.2, 108.6, 107.9, 101.6, 69.0, 61.3, 58.4, 56.4, 53.6, 52.9, 47.5, 43.6, 42.0, 37.2, 29.4, 27.4, 26.8; HRMS (ESI) for C62H77N6O16 m/z (M+H)+: calcd 1161.5391, obsd 1161.5407; mp: 152–155 °C; yield: 41%.

5.1.6 N-[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]-2-{4-[10-(piperazin-1-yl)decyl]piperazin-1-yl}acetamide (6d)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 7.31 (s, 2H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.59 (s, 1H), 6.29 (s, 2H), 6.04 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 5.26 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (t, J = 7.6, 8.7 Hz,1H), 3.87-3.80 (m, 7H), 3.15-2.90 (m, 7H), 2.84-2.79 (m, 1H), 2.58-2.25 (m, 15H), 1.44-1.28 (m, 16H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 174.3, 170.6, 148.3, 147.6, 146.6, 134.3, 132.5, 130.0, 129.1, 110.2, 108.5, 107.9, 101.6, 69.0, 61.3, 59.3, 58.5, 56.4, 54.0, 53.7, 52.9, 47.5, 45.7, 43.6, 42.0, 37.2, 29.5, 27.5, 26.9, 26.6; HRMS (ESI) for C41H60N5O8 m/z (M+H)+: calcd 750.4436, obsd 750.4465; mp: 135–140°C; yield: 36%.

5.1.7 2-(4-{10-[4-({[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1(9),2,7-trien-10-yl]carbamoyl}methyl)piperazin-1-yl]decyl}piperazin-1-yl)-N-[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]acetamide (7d)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 7.25 (s, 1H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.01 (d, J = 1.29 Hz, 2H), 5.49 (bs, 1H), 5.26 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (t, J = 7.8, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.87-3.80 (m, 7H), 3.46-3.51 (m, 1H), 3.10 (d, J = 8.04 Hz, 2H), 2.94-3.02 (m, 1H), 2.85 (dd, J = 4.8, Hz, 1H) 2.64-2.25 (m, 10H), 1.64-1.20 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 174.3, 170.5, 148.3, 147.6, 146.5, 134.2, 132.5, 130.1, 129.1, 110.2, 108.6, 107.9, 101.6, 69.0, 61.3, 58.5, 56.4, 53.6, 52.9, 47.5, 43.6, 42.0, 37.2, 29.5, 27.5, 26.8; HRMS (ESI) for C64H81N6O16 m/z (M)+: calcd 1189.5704, obsd 1189.5686; mp: 178–182 °C; yield: 54%.

5.1.8 2-(4-{12-[4-({[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca-1(9),2,7-trien-10-yl]carbamoyl}methyl)piperazin-1-yl]dodecyl}piperazin-1-yl)-N-[(10S,11S,15R,16R)-16-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-14-oxo-4,6,13-trioxatetracyclo[7.7.0.03,7.011,15]hexadeca 1,3(7),8-trien-10-yl]acetamide (7e)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ 7.32 (s, 1H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.01 (s, 2H), 5.40 (bs, 1H), 5.22 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (t, J = 7.8, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.87-3.80 (m, 7H), 3.16-2.93 (m, 3H), 2.85-2.79 (dd, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.65-2.24 (m, 10H), 1.52-1.20 (m, 10H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz): δ 174.3, 170.5, 148.3, 147.6, 146.5, 134.2, 132.5, 130.1, 129.1, 110.2, 108.6, 107.9, 101.6, 69.0, 61.3, 58.5, 56.4, 53.6, 52.8, 47.5, 43.6, 41.9, 37.2, 29.5, 27.5, 26.8; HRMS (ESI) for C66H85N6O16 m/z (M+H)+: calcd 1217.6017, obsd 1217.6039; mp: 142–145°C; yield: 68%.

5.2 Materials, cell culture and growth inhibition assays

Unless specified, reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Canada). The extraction and purification of recombinant full-length human topoisomerase IIα were described previously.38 Human leukemia K562 cells, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and K/VP.5 cells (a 26-fold etoposide-resistant K562-derived sub-line with decreased levels of topoisomerase IIα mRNA and protein)29 were maintained as suspension cultures in αMEM (Invitrogen, Burlington, Canada) containing 10% fetal calf serum. The spectrophotometric 96-well plate 72 h cell growth inhibition MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI) has been described previously.14,33 The drugs were dissolved in DMSO and the final concentration of DMSO did not exceed an amount (typically 0.4% or less) that had any detectable effect on cell growth. The IC50 values for cell growth inhibition were measured by fitting the absorbance-drug concentration data to a four-parameter logistic equation as described.14,33 Typically nine different drug concentrations, determined in duplicate and measured on two different days, were used to characterize the growth inhibition curves. The catenated kDNA and the primary anti-topoisomerase IIα antibody were from TopoGEN (Port Orange, FL) and Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX), respectively, and the secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

5.3 Topoisomerase IIα kDNA decatenation, pBR322 DNA relaxation and cleavage assays

A gel assay as previously described14,33 was used to determine if the compounds inhibited the catalytic decatenation activity of topoisomerase IIα. kDNA, which consists of highly catenated networks of circular DNA, is decatenated by topoisomerase IIα in an ATP-dependent reaction to yield individual minicircles of DNA. Topoisomerase II-cleaved DNA covalent complexes produced by anticancer drugs may be trapped by rapidly denaturing the complexed enzyme with SDS.14,31,33 The drug-induced cleavage of double-strand closed circular plasmid pBR322 DNA to form linear DNA at 37 °C was followed by separating the SDS-treated reaction products by ethidium bromide gel electrophoresis, essentially as described, except that all components of the assay mixture were assembled and mixed on ice prior to addition of the drug.14,31,33

5.4 γH2AX assay for DNA double-strand breaks in drug-treated K562 cells

The γH2AX assay was carried essentially out as described.14,33 K562 cells in growth medium (1.5 mL in a 24-well plate, 3.4 × 105 cells/mL) were incubated with drug or with DMSO vehicle control for 4 h at 37 °C. The lysis buffer (pH 6.7, 60 mM Tris) also contained 10% glycine, 2% SDS, 5% mercaptoethanol, and 0.002% bromophenol blue. Cell lysates (50 μg protein) were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 14% gel. Separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, and then treated overnight with rabbit anti-γH2AX (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA) primary antibody diluted 1:1000. This was followed by incubation for one h with both peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) diluted 1:2000, and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology) primary antibody diluted 1:1000. After incubation with luminol/enhancer/peroxide solution (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Canada), chemiluminescence of the γH2AX and GAPDH bands were imaged on a Cell Biosciences (Santa Clara, CA) FluorChem FC2 imaging system equipped with a charge-coupled-device camera.

5.5 Cell cycle synchronization, cell cycle analysis and annexin V flow cytometry

The cell cycle synchronization experiments were carried out as previously described for the determination of the proportion of cells in sub-G0/G1, G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle.14,33 For the synchronization experiments CHO cells were grown to confluence in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS. Following serum starvation with α-MEM-0% FCS for 48 h, the cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/mL, repleted with α-MEM-10% FCS. Directly after repletion they were continuously treated with either 1 μM of the compound indicated or 10 μM etoposide in 35-mm diameter dishes for different periods of time.

The fraction of apoptotic cells induced by treatment of K562 cells with the compounds and the etoposide positive control were quantified by two-color flow cytometry by simultaneously measuring integrated green (annexin V-FITC) fluorescence, and integrated red (propidium iodide) fluorescence as we previously described.14,33 The annexin V-FITC binding to phosphatidylserine present on the outer cell membrane was determined using an Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Canada). Briefly, K562 cells in suspension (1 × 106 cells/ml) were untreated or treated with either 1 μM of the compound indicated or 10 μM etoposide at 37°C for either 24 h or 48 h.

5.6 Caspase-3/7 apoptosis assay

The caspase-3/7 assay that measures caspase-3 and caspase-7 activities was carried out on K562 lysates as we previously described for myocytes36 on a BMG (Cary, NC) Fluostar Galaxy plate reader in luminescence mode according to the manufacturer’s directions (Caspase-Glo 3/7, Promega, Madison, WI). The assay utilizes a proluminescent caspase-3/7 DEVD-aminoluciferin substrate to produce a luminescent signal proportional to caspase-3/7 activity. K562 cells were treated with either the vehicle control or 1 μM of the compounds indicated for either 24 or 48 h at a cell density of 2 × 105 cells/mL.

5.7 Molecular modeling and docking of the bis-epipodophyllotoxins into an X-ray structure of etoposide complexed to cleaved DNA and topoisomerase IIβ

The molecular modeling and the docking were carried out as described14 using the genetic algorithm docking program GOLD version 3.2 (CCDC Software, Cambridge, UK) with default GOLD parameters and atom types and with up to 2000 starting runs. The major diprotonated microspecies at pH 7.4 of the bis-epipodophyllotoxins were docked into both etoposide binding sites of the X-ray structure (www.rcsb.org/pdb; PDB ID: 3QX3)5 which contains two molecules of etoposide complexed to cleaved DNA and topoisomerase IIβ. The structure was prepared by removing the etoposide molecules, the water molecules and Mg2+ to avoid potential interference with the docking. In order to obtain satisfactory docking solutions of these highly conformationally flexible molecules into the two etoposide binding sites, three distance constraints on each epipodophyllotoxin moiety were used. Docked poses in which the epipodophyllotoxin moiety of the bis-epipodophyllotoxins differed from that of the X-ray determined etoposide poses were given a penalty score. The three atoms on the epipodophyllotoxin moiety of etoposide used to set the distance constraints are denoted with asterisks in Figure 7. The two atoms on the polycyclic moiety and an atom on the pendant phenolic group were chosen to orient the core epipodophyllotoxin structure into a bound etoposide-like pose. Their respective distance constraint partners were the closest heavy atoms in the X-ray structure. Etoposide docked without constraints back into its topoisomerase IIβ-DNA structure with a heavy atom r.m.s. distance of 0.48 Å,14 compared to the X-ray structuredetermined pose.5 Values of 2.0 Å or less in the extensive GOLD test set are considered to be good.39 The graphics were prepared with DS Visualizer 2.5 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA). MarvinSketch and its associated calculator plugins were used for displaying the compounds and calculating the major protonated microspecies present at pH 7.4 (Marvin version 6, 2013, ChemAxon, http://www.chemaxon.com).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MOP13748), the Canada Research Chairs Program, and a Canada Research Chair in Drug Development to Brian Hasinoff and an NIH grant CA090787 to Jack Yalowich. The authors declare no competing financial interests. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACN, acetonitrile; Boc, di-tert-butyl dicarbonate; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; DCM, dichloromethane; DMF, dimelthylformamide; ESI, electrospray ionization; Et3N, triethylamine; ICE, immunodetection of complexes of enzyme-to-DNA; kDNA, catenated DNA; K562 cells, human erythroleukemic cells; HRMS, high resolution mass spectrometry; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium; r.m.s., root-mean-square; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; αMEM, Minimal Essential Medium Alpha.

Supplementary data from the National Cancer Institute (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov) NCI-60 cell line panel testing results for compounds 7a, 7b and 7d and the NMR data) associated with this article can be found in the online version, at http://xx.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Pommier Y. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:82–95. doi: 10.1021/cb300648v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nitiss JL. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:338–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deweese JE, Osheroff N. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:738–748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pommier Y, Marchand C. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:25–36. doi: 10.1038/nrd3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu CC, Li TK, Farh L, Lin LY, Lin TS, Yu YJ, Yen TJ, Chiang CW, Chan NL. Science. 2011;333:459–462. doi: 10.1126/science.1204117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu CC, Li YC, Wang YR, Li TK, Chan NL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:10630–10640. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CC, Wang YR, Chen SF, Wu CC, Chan NL. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow KC, Macdonald TL, Ross WE. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;34:467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross W, Rowe T, Glisson B, Yalowich J, Liu L. Cancer Res. 1984;44:5857–5860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentry AC, Pitts SL, Jablonsky MJ, Bailly C, Graves DE, Osheroff N. Biochemistry. 2011;50:3240–3249. doi: 10.1021/bi200094z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.You Y. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1695–1717. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chee GL, Yalowich JC, Bodner A, Wu X, Hasinoff BB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:830–838. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasinoff BB, Chee GL, Day BW, Avor KS, Barnabé N, Thampatty P, Yalowich JC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:1765–1771. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadav AA, Wu X, Patel D, Yalowich JC, Hasinoff BB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:5935–5949. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang R, Wu X, Yalowich JC, Hasinoff BB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:7023–7032. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasinoff BB, Zhang R, Wu X, Guziec LJ, Guziec FS, Jr, Marshall K, Yalowich JC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:4575–4582. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasinoff BB, Liang H, Wu X, Guziec LJ, Guziec FS, Jr, Yalowich JC. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:3959–3968. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjorndal MT, Fygenson DK. Biopolymers. 2002;65:40–44. doi: 10.1002/bip.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saulnier MG, Langley DR. 4965348A. US Patent. 1990

- 20.Rothenborg-Jensen L, Hansen HF, Wessel I, Nitiss JL, Schmidt G, Jensen PB, Sehested M, Jensen LH. Anticancer Drug Des. 2001;16:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duca M, Guianvarc’h D, Oussedik K, Halby L, Garbesi A, Dauzonne D, Monneret C, Osheroff N, Giovannangeli C, Arimondo PB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1900–1911. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duca M, Oussedik K, Ceccaldi A, Halby L, Guianvarc’h D, Dauzonne D, Monneret C, Sun JS, Arimondo PB. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:873–884. doi: 10.1021/bc050031p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passarella D, Peretto B, Blasco y Yepes R, Cappelletti G, Cartelli D, Ronchi C, Snaith J, Fontana G, Danieli B, Borlak J. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen HF, Jensen RB, Willumsen AM, Norskov-Lauritsen N, Ebbesen P, Nielsen PE, Buchardt O. Acta Chem Scand. 1993;47:1190–2000. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.47-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang ZG, Yin SF, Ma WY, Li BS, Zhang CN. Acta Pharm Sin. 1993;28:422–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards C, Ray NC, Gill MIA, Alcindor J, Finch H, Fitzgerald MF. 2007042815A1. WO. 2007

- 27.Ritke MK, Allan WP, Fattman C, Gunduz NN, Yalowich JC. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritke MK, Roberts D, Allan WP, Raymond J, Bergoltz VV, Yalowich JC. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:687–697. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fattman C, Allan WP, Hasinoff BB, Yalowich JC. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasinoff BB, Wu X, Nitiss JL, Kanagasabai R, Yalowich JC. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:1617–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burden DA, Froelich-Ammon SJ, Osheroff N. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;95:283–289. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-057-8:283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pilch DR, Sedelnikova OA, Redon C, Celeste A, Nussenzweig A, Bonner WM. Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;81:123–129. doi: 10.1139/o03-042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasinoff BB, Wu X, Yadav AA, Patel D, Zhang H, Wang DS, Chen ZS, Yalowich JC. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93:266–276. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clifford B, Beljin M, Stark GR, Taylor WR. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4074–4081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang YJ, Zhou ZX, Wang GW, Buridi A, Klein JB. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13690–13698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasinoff BB, Patel D, Wu X. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2013;13:33–47. doi: 10.1007/s12012-012-9183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wendorff TJ, Schmidt BH, Heslop P, Austin CA, Berger JM. J Mol Biol. 2012;424:109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasinoff BB, Wu X, Krokhin OV, Ens W, Standing KG, Nitiss JL, Sivaram T, Giorgianni A, Yang S, Jiang Y, Yalowich JC. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:937–947. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdonk ML, Cole JC, Hartshorn MJ, Murray CW, Taylor RD. Proteins. 2003;52:609–623. doi: 10.1002/prot.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.