Abstract

Viruses with small circular rep-encoding ssDNA (CRESS-DNA) genomes can infect a wide range of eukaryotic organisms ranging from mammals to fungi. The genomes of two novel CRESS-DNA viruses, a cyclovirus (CyCV-SL) and gemycircularvirus (GemyCVSL) were detected by deep sequencing of the cerebrospinal fluids of Sri Lankan patients with unexplained encephalitis. One and three out of 201 CSF samples (1.5%) from unexplained encephalitis patients tested by PCR were CyCV-SL and GemyCV-SL DNA positive respectively. Nucleotide similarity searches of pre-existing datasets revealed related genomes in feces from unexplained cases of diarrhea from Nicaragua and Brazil and in untreated sewage from Nepal. Whether the tropism of the cycloviruses and gemycircularviruses reported here include humans or their detection reflects production from other cellular sources in or on the human body remains to be determined.

Keywords: cyclovirus, gemycircularvirus, encephalitis, diarrhea, CRESS-DNA

Introduction

Cyclovirus is a recently proposed genus of the Circoviridae family with small ssDNA circular genome of approximately 2-kb (Li et al., 2010a). Cycloviruses are a sister clade to the circoviruses, a genus known to infect a wide variety of birds (Todd, 2004) and mammals (Li et al., 2013; Li et al., 2011). A third genus, krikovirus, was recently proposed from genomes detected in mosquitoes (Garigliany et al., 2014) and bat feces (Li et al., 2010b; Lima et al., 2015). Members of the Circoviridae family are part of a much more diverse group of viruses with circular, replication associated protein (Rep) encoding, single stranded DNA (CRESS-DNA) genomes found in a wide range of hosts and environment (Delwart and Li, 2012; Rosario et al., 2012b). CRESS-DNA viruses, encoding only Rep and capsid protein (Cap), have the smallest genomes of autonomously replicating eukaryotic viruses. Cyclovirus genomes, initially found in the feces of Pakistani children with and without acute flaccid paralysis (Li et al., 2010a) have also been reported in the feces of bats (Ge et al., 2011; Li et al., 2010b), poultry (Li et al., 2010a; Li et al., 2011; Tan le et al., 2013) and in meat samples of various farm animals in Pakistan and Nigeria (Li et al., 2010a; Li et al., 2011). Cyclovirus genomes have also been detected in the abdomen of dragonflies and in the Florida cockroach (Dayaram et al., 2013; Padilla-Rodriguez et al., 2013; Rosario et al., 2011). In 2013 another distinct cyclovirus was reported in 4% of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from south and central Vietnamese children with unexplained central nervous system disorders, and in 4.2% of healthy children’s feces (Tan le et al., 2013). Fifty eight percent of feces from nearby pigs were also positive for the same cyclovirus DNA (Tan le et al., 2013). A later study failed to detect this virus in CSF of similar patients from northern Vietnam, Cambodia, Nepal and The Netherlands (Le et al., 2014). Also in 2013 another cyclovirus was found in 10% of CSF and 15% of sera from 58 paraplegia (leg paralysis) Malawian adult patients (Smits et al., 2013). These CSF associated cyclovirus genomes phylogenetically clustered together along with Tunisian strains from the feces of children with non-polio acute flaccid paralysis (Li et al., 2010a; Li et al., 2011). In addition an additional cyclovirus species was detected in 3% of nasopharyngeal aspirates from Chilean infants with unexplained acute lower respiratory tract infections (Phan et al., 2014). Detection of cyclovirus DNA in various tissue samples, human feces, CSF, blood, and respiratory secretion, and in farm animal meat suggests systemic infections although with the caveat that replication in mammalian cells and sero-conversion remains to be demonstrated. The detection of cyclovirus sequences by PCR in sewage water from cities in the US reflects the presence of cycloviruses in industrialized countries (Blinkova et al., 2009).

Recently, another distinct group of CRESS-DNA genomes from diverse sources were classified under the proposed genus name of Gemycircularvirus (Rosario et al., 2012a; Sikorski et al., 2013). The members of this proposed genus are also called myco-like viruses because of their overall genome similarity to those of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum hypovirulence-associated DNA virus 1 (SsHADV-1), the first DNA virus found replicating in fungi (Yu et al., 2010). Other gemycircularvirus genomes have also been identified in feces of different animals (Sikorski et al., 2013; van den Brand et al., 2012), cassava infecting fungi (Dayaram et al., 2012), the body of insects (Dayaram et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2011; Rosario et al., 2012a), and sewage (Kraberger et al., 2015). Gemycircularvirus genomes were also recently reported in blood from a patient with multiple sclerosis and asymptomatic cattle (Lamberto et al., 2014).

Here we report on the detection of both cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus DNA in the CSF of encephalitis patients, in fecal samples of unexplained human diarrhea, as well as in untreated sewage from Katmandu, Nepal.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

CSF samples were collected from patients with encephalitis in Sri Lanka. These included 29 children aged between 2 and 144 months old and 33 adults between 15 and 72 years old. These samples had pre-tested negative for bacteria, herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, dengue virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, rubella virus, west nile virus, yellow fever virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, nipah virus, measles virus, mumps virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, metapneumovirus, chikungunya virus, sindbis virus, semliki forest virus, eastern equine encephalitis virus, western equine encephalitis virus, poliovirus, coxsackievirus, echovirus, enterovirus, lyssaviruses, chandipura virus, bocavirus, rotavirus, astrovirus, norovirus, parechovirus, and adenovirus (Mori et al., 2013).

Viral metagenomics

The 62 CSF samples from Sri Lankan patients were first analyzed in minipools of 4-5 samples using a metagenomics approach. Total nucleic acids were extracted using a Maxwell® 16 automated extractor (Promega) from supernatant of CSF spun 15 min in a microfuge. cDNA and DNA were then generated by using random RT-PCR followed by the use of the Nextera™ XT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) to construct a DNA library. One Illumina MiSeq run of 250 bases paired-end reads yielded an average of 2.56 million sequence reads from each pool of clinical samples. After quality control removal of duplicate reads and reads shorter than 50 bases followed by de novo assembly, viral sequences were identified through translated protein sequence similarity search (BLASTx) to annotated viral proteins available in GenBank’s viral RefSeq database.

Genome acquisition of novel circular viruses

The complete genomes of circular viruses were identified and recovered by de novo-assembly, inverse PCR and Sanger sequencing. Putative ORFs in the circular genomes were identified using the NCBI ORF finder. The secondary structure of intergenic regions was predicted using the Mfold program (Zuker, 2003). All alignments and phylogenetic analyses were based on the translated amino acid sequences. Sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTAL X with the default settings (Saitou and Nei, 1987). Sequence identities were determined using BioEdit. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using Rep and Cap proteins of novel circular viruses and other genetically-close relatives. Phylogenetic trees with 100 bootstrap resamples of the alignment data sets were generated using the neighbor-joining method and visualized using the program MEGA version 5 (Tamura et al., 2011). Bootstrap values (based on 100 replicates) for each node are shown if >70%.

PCR assays for cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus

In order to understand the frequency of cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus, we designed two sets of primers to amplify segments of the viral genomes and used nested-PCR to screen other CSF samples from Sri Lanka.

For cyclovirus, primers SLCyV-F1 (5[g397]-TCC GTC CCA CCA TAG TCC TCT-3[g397]) and SLCyV-R1 (5[g397]-AAG CAT CTC CAT AAC TCA ATC CAT CT-3[g397]) were used for the first round of PCR, and primers SLCyV-F2 (5[g397]-TTG ATT GGT TTG TTG CTT TTG CTT CTT CT-3[g397]) and SLCyV-R2 (5[g397]-GTA GCC AAG GAC ATC GCT CAG A-3[g397]) for the second round of PCR.

For gemycircularvirus, primers SLGemy-F1 (5[g397]-GTG GTA ATG GTC GTC GGT ATT C-3[g397]) and SLGemy-R1 (5[g397]-CCT CAT CAT TCG TAG TAA GCA ATC TCA-3[g397]) were used for the first round of PCR, and primers SLGemy-F2 (5[g397]-AGT CCT GAA TGT TTC CAC TCG-3[g397]) and SLGemy-R2 (5[g397]-CAA GCG TTC CCT CGA AAA TGA C-3[g397]) for the second round of PCR.

The PCR conditions in these two assays were: 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles 95°C for 30s, 50°C (for the first or second round) for 30s and 72°C for 1 min, a final extension at 72°C for 10 min, resulting in an expected amplicon of 255-bp for cyclovirus and 476-bp for gemycircularvirus.

PCR assay for fungi

Semi-nested PCR with universal primers for fungal amplification were performed. Primers ITS1 (5[g397]-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G-3[g397]) and ITS4 (5[g397]-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3[g397]) were used for the first round of PCR. Primers ITS86 (5[g397]-GTG AAT CAT CGA ATC TTT GAA C-3[g397]), and ITS4 were used for the second round of PCR. The PCR condition was followed as previously published, producing an expected amplicon of 280-bp (Ferrer et al., 2001).

Results

The genomes of novel cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus were identified by deep sequencing the CSFs from 62 Sri Lankan patients with unexplained encephalitis (Materials and Methods). These CSF samples had previously tested negative for a wide range of pathogens (Materials and Methods). Using a BLASTx cutoff of E scores <10−5 one pool of five CSF samples containing 1.42×106 sequence reads showed a single read of human enterovirus B, 247 reads related to cycloviruses, and 6 reads related to gemycircularvirus. Total nucleic acids of the individual samples within the pool containing these sequences were extracted and tested for the cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus sequences by PCR - identifying two individual CSF samples. The complete genomes of these two CRESSDNA viruses were then acquired by inverse PCR and sequenced.

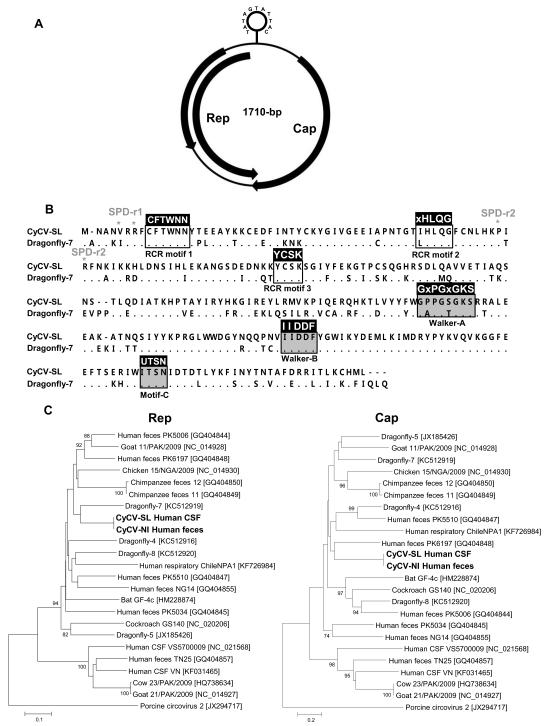

The circular genome of the cyclovirus, referred to as human CyCV-SL, was 1710 bases, with a GC content of 41%, including the major ORFs for Rep and Cap (GenBank KJ831064). The intergenic region is 207-bp and contains a stem loop structure with a stem of 13-bp. Similar to other cycloviruses, the highly conserved nonamer [TAGTATTAC] was found in the loop (Figure 1A). The Rep protein that has 276-aa in length showed the closest identity (71%) to that of dragonfly cyclovirus-7 (GenBank KC512919) with the next closest Rep from cyclovirus PK5006 found in human feces (GenBank GQ404844) at 70% identity. The Cap protein (230-aa) shared highest identity of 39% at the amino acid level to dragonfly cyclovirus-7 with the next closest Rep from cyclovirus PK6197 found in human feces (GenBank GQ404848) at 36% identity. Analysis of the deduced amino acid Rep sequences of human CyCV-SL revealed three rolling circle replication motifs I-III, CFTWNN, IHLQG and YCSK, respectively [conserved amino acid in boldface] (Rosario et al., 2012b) (Figure 1B). In the N-terminus of the cyclovirus Rep, two consensus high-affinity DNA binding specificity determinants (SPDs), TxR for SPD-region 1 and PxR for SPD-region 2, were present (Dayaram et al., 2013; Londono et al., 2010). The CyCV-SL Rep showed a mutated VxR for SPD-region 1 (Figure 1B). The C-terminal region of the Rep possessed ATP-dependent helicase motifs Walker A (GPPGSGKS), B (IIDDF) and C (UTSN) [conserved amino acid in boldface] (Rosario et al., 2012b) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. New cyclovirus.

A. Genome organization and its stem loop structure. B. Alignment of Rep proteins of the newly identified Sri Lankan cyclovirus and dragonfly cyclovirus-7. Conserved motifs were shown. C. Phylogenetic trees generated with Rep and Cap proteins of cycloviruses detected in a Sri Lanka patient with unexplained encephalitis, in a Nicaraguan patient with unexplained diarrhea, and all genetically-related cycloviruses in the genus Cyclovirus. The scale indicates amino acid substitutions per position.

Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that CyCV-SL is distinct from other known members of the Cyclovirus genus (Figure 1C). A recent ICTV proposal has set a genome identity of >80% for members of the same circovirus or cyclovirus species. Our pair-wise genetic analysis revealed that CyCV-SL shared only 60% nucleotide identity over the entire genome and 39% amino acid identity for the capsid protein to the closest cyclovirus genome. CyCV-SL is therefore proposed as prototype of a novel species in the Cyclovirus genus.

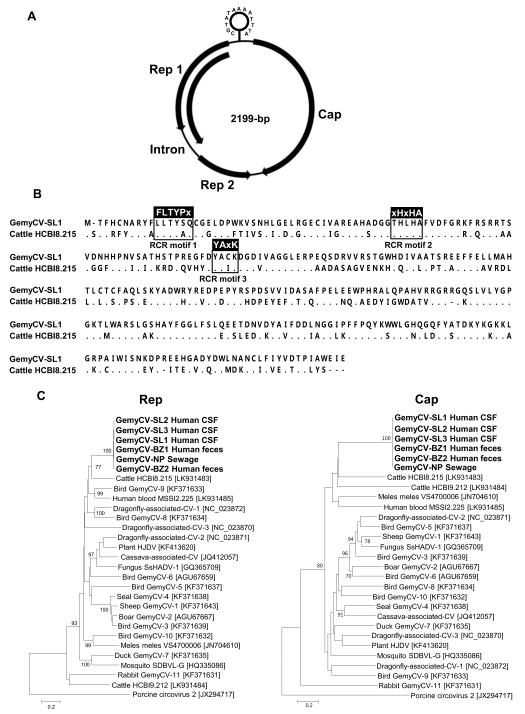

The genome of a new gemycircularvirus which we named GemyCV-SL1 was similarly amplified and sequenced from another CSF sample yielding a 2199 bases genome, including major Rep1 (194-aa), minor Rep2 (112-aa) and Cap (322-aa) (GenBank KP133075). The intergenic region (127-nt) contained a stem loop structure having an atypical nonamer [TAAAATTTA] (Figure 2A) (Sikorski et al., 2013). Similar to other members of the Gemycircularvirus genus GemyCV-SL1 had a unique intron (140-nt) between two Rep ORFs. Intron splicing resulted in a single Rep ORF 320-aa in length. Rep and Cap proteins showed the highest identity (56% and 31%) to those of gemycircularvirus HCBI8.215 found in healthy cattle blood (GenBank LK931483) (Lamberto et al., 2014). The spliced Rep protein in GemyCV-SL1 possessed three rolling circle replication motifs I-III (LLTYSG, THLHA and YACK) [conserved amino acid in boldface] (Rosario et al., 2012b) (Figure 2B). Genetic analysis of the C-terminal region of the spliced Rep also detected three ATP-dependent helicase motifs Walker A (GPSRMGKT), B (IFDDL) and C (WISN) [conserved amino acid in boldface] (Rosario et al., 2012b) (Figure 2B). Phylogenetic analysis confirmed GemyCV-SL1 to be related to gemycircularvirus HCBI8.215 (Figure 2C). GemyCV-SL1 therefore represents a new candidate species in the Gemycircularvirus genus.

Figure 2. New gemycircularvirus.

A. Genome organization and its stem loop structure. B. Alignment of Rep proteins of the newly identified Sri Lankan gemycircularvirus and cattle gemycircularvirus. Conserved motifs were shown. C. Phylogenetic trees generated with Rep and Cap proteins of gemycircularvirus detected in Sri Lanka patients with unexplained encephalitis, Brazilian patients with unexplained diarrhea, Nepalese sewage, and all genetically-related gemycircularviruses in the Gemycircularvirus genus. The scale indicates amino acid substitutions per position.

Two nested PCR assays were developed to determine the prevalence of these viruses in the Sri Lankan CSF samples. In order to confirm the presence of these two novel viruses in the Sri Lankan CSF samples and exclude the possibility of local DNA contamination, the same two PCR protocols were also used by an independent lab at Oita University, Japan. This lab had previously extracted the same 62 CSF samples by QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) and tested them for nucleic acids of known viruses (Mori et al., 2013) . The presence of both CyCV-SL and GemyCV-SL1 DNA were confirmed by PCR in the same two samples. The Oita University lab also PCR screened for these two CRESS-DNA viruses in another set of 139 CSF samples previously extracted by QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) from similar Sri Lankan patients with unexplained encephalitis. No other CyCV-positive sample was detected but GemyCV DNA was amplified in 2 out these 139 nucleic acids extracts, yielding a total frequency of GemyCV DNA detection of 1.5% (3/201). The full genomes of these two GemyCVs were then acquired by inverse PCR and direct Sanger sequencing. Nucleotide alignment showed that the genomic sequences of GemyCV-SL2 and -SL3 (Genbank KP133076 and KP133077) showed three and six nucleotide mutations to the GemyCV-SL1 genome, respectively.

Nucleotides sequences closely related to CyCV-SL and GemyCV-SL were then sought using MegaBlast in 135 MiSeq and 60 pyrosequencing (454 Roche) runs previously generated in the San Francisco laboratory with other human, animals, and environmental samples. In one Miseq run, four CyCV-SL sequence matches were found among 6.2 × 105 reads generated from one pool of five unexplained human diarrhea samples from Nicaragua (Bucardo et al., 2014). In another Miseq run, fourteen GemyCV-SL sequences were found in 3.2 × 106 reads generated from one pool of five unexplained human diarrhea feces from Brazil. A total of eighty-three GemyCV-SL sequences were also found among 5,915 reads generated by 454 pyrosequencing from raw sewage from Nepal (Ng et al., 2012). Total nucleic acids of individual feces samples within the Nicaraguan and Brazilian diarrhea sample pools were extracted and each was tested by PCR. One Nicaraguan and two Brazilian samples were found to be PCR positive. The DNA from these three samples were then used to generate the complete genomes by inverse PCR yielding Nicaraguan cyclovirus (CyCV-NI, 1710 bases, Genbank KP151567), and two Brazilian gemycircularvirus (GemyCV-BZ1 and GemyCV-BZ2, both 2199 bases, Genbank KP133078 and KP133079). The Nepalese sewage gemycircularvirus (GemyCV-NP, 2199 bases, Genbank KP133080) was also acquired by inverse PCR and Sanger sequencing. Nucleotide alignment showed the CyCV-NI genome to differ by 72 nucleotide mutations relative to CyCV-SL1 (95.8% identity). The genomes of GemyCV-BZ1 and -BZ2, and GemyCV-NP showed 32, 31, 29 nucleotide mutations to the GemyCV-SL1. The two Brazilian GemyCV genomes in two individual feces samples differed by 26 nucleotides.

To exclude the possibility of contamination from the DNA extraction method used we re-extracted all of the originally cycloviruses and gemycircularviruses positive CSF, feces and sewage samples (except GemyCV-SL2 and -SL3 as only previously extracted DNA was available) using phenol-chloroform extraction and confirmed the presence of cyclovirus and GemyCV by PCR.

To determine whether other viruses were also present in the samples containing cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus which might account for the diseased state of the patients their nucleic acids were individually deep sequenced and analyzed against all eukaryotic viruses (Table 1). The Sri Lankan CSF sample, in which the cyclovirus was first identified and sequenced, showed 438 CyCV-SL reads out of 3.2 ×105 reads. No other viral sequences were identified. The three individual Sri Lankan CSF samples positive for gemyCV by PCR all yielded gemyCV reads (n=14 to 116) and no other virus except for anelloviruses in two samples. No cyclovirus sequences were detected in the individual Nicaraguan feces positive by PCR possibly due to a low viral load as reflected by the few sequence reads (n=4) detected in the previously sequenced pool. 1,185 human adenovirus 41 sequences read were detected in that fecal sample. For the two individual Brazilian fecal samples positive for gemyCV by PCR one yielded 4 gemyCV-BZ1 reads and the other none. No other eukaryotic viruses were detected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detection of cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus reads in deep sequencing of pools and individual samples.

| Source | Genome sequenced |

Country | PCR Detection |

Miseq reads |

GemyCV reads |

CyCV reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF pool | Sri Lanka | + | 1429342 | 6 | 247 | |

| CSF | CyCV-SL | Sri Lanka | + | 322060 | 438 | |

| CSF | GemyCV-SL1 | Sri Lanka | + | 2925070 | 72 | |

| CSF | GemyCV-SL2 | Sri Lanka | + | 866078 | 116 | |

| CSF | GemyCV-SL3 | Sri Lanka | + | 1269398 | 14 | |

| Feces pool |

Nicaragu a |

+ | 625641 | 4 | ||

| Feces | CyCV-NI | Nicaragu a |

+ | 753634 | ||

| Feces pool |

Brazil | + | 3214352 | 14 | ||

| Feces | GemyCV-BZ1 | Brazil | + | 3652720 | 4 | |

| Feces | GemyCV-BZ2 | Brazil | + | 753614 |

To investigate the possibility of a fungal origin for gemyCV, we used semi-nested PCR with universal fungal ITS2/5.8S rDNA primers on the three gemyCV-positive CSF samples and on five Sri Lankan gemyCV-negative CSF samples from Sri Lankan. The three gemyCV-positive CSF samples were negative for fungal DNA while one of five gemyCV-negative CSF samples was positive. Sequence analysis of the amplicon indicated the presence of Cryptococcus victoriae DNA, a widely distributed fungal species (Danesi et al., 2014; Gallardo et al., 2014; Montes et al., 1999).

Discussion

We describe the genomes of a cyclovirus and gemycircularvirus in CSF from unexplained cases of encephalitis in Sri Lanka. Closely related viruses where also detected in unexplained human diarrhea samples from Nicaragua and Brazil as well as in untreated sewage from Nepal. In all but one case no other eukaryotic sequences were detected by deep sequencing indicating a potential role for these viruses in these patients’ symptoms. In one sample adenovirus 41 was detected as a likely cause of the patient’s diarrhea (Cruz et al., 1990; Sdiri-Loulizi et al., 2008; Sdiri-Loulizi et al., 2009).

While identifying CRESS-DNA genomes in CSF, a site considered sterile, supports the possibility of replication in the human host; however, reports confirming replication in mammalian cells or of sero-conversion to these viruses are still lacking. Because prior reports have detected distinct cycloviral genomes in the abdomen of insects (Dayaram et al., 2013; Padilla-Rodriguez et al., 2013; Rosario et al., 2011) alternative explanation should be considered to explain their detection in CSF. Cycloviruses may have a wide tropism with some species infecting mammals while others infect insects. Some cyclovirus species may be arboviruses capable of replication in both insects and mammals infected through insect bites. Cyclovirus DNA in mammalian fecal samples may be the result of consuming food contaminated with cyclovirus-infected insects after transiting of the virus through the digestive track as observed for chicken anemia virus DNA in human feces (Chu et al., 2012; Phan et al., 2012) and insect viruses in feces of insectivorous bats (Donaldson et al., 2010; Ge et al., 2012; Li et al., 2010b; Reuter et al., 2014). Cycloviruses in sites considered sterile such as CSF and plasma may also conceivably result from contamination during sample collection with the needle introducing a small skin plug into the collected biological fluid. The detection of cyclovirus DNA (Foulongne et al., 2012) as well as a gyrovirus, polyomaviruses, and papillomavirus DNA on human skin swabs attest to the frequent presence of numerous viral genomes on the skin surface (Ekstrom et al., 2013; Foulongne et al., 2012; Hannigan and Grice, 2013; Sauvage et al., 2011; Schowalter et al., 2010).

The origin of the gemycircularvirus DNA found here in CSF and recently described in human and bovine plasma (Whitley et al., 2014) also remains uncertain. To date the only cellular host identified is for the prototype of this group, SsHADV-1, the first DNA virus shown to replicate in fungi (Yu et al., 2010). The cellular hosts of all other gemycircularviruses, many detected in feces of mammals (Sikorski et al., 2013; van den Brand et al., 2012), fungi-infected plants (Dayaram et al., 2012), insects (Dayaram et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2011; Rosario et al., 2012a), and sewage (Kraberger et al., 2015) remains uncertain. As is the case for cycloviruses, the detection of gemycircularvirus genome in mammalian feces, blood, and CSF, may reflect genuine viral replication in humans or alternatively fungal infection releasing virus into the blood stream, fungi or fungi-infected plants in the diet, contamination from the skin’s surface during phlebotomy, or even contamination from particles floating in air (Whon et al., 2012). Whether any gemycircularvirus actually replicates in mammalian cells or simply reflects the presence of other cellular organisms remains uncertain despite their genomes’ detection in “sterile” sites.

Among CRESS-DNA viruses only members of the circovirus genus, such as pig and canine circoviruses (Li et al., 2013; Todd et al., 2001), have been shown to replicate in mammals. The cellular hosts of the large majority of CRESS-DNA encoded viruses, recently brought to light using deep sequencing methods, remain unknown (Delwart and Li, 2012; Rosario et al., 2012b). Further studies are required to assign cellular hosts to cycloviruses and gemycircularviruses detected in human feces and tissues.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by NHLBI grant R01 HL105770 to E.L.D and the Blood Systems Research Institute, and a Research Fund at the Discretion of the President, Oita University (grant no. 610000-N5021) to K.A.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The GenBank accession numbers for new cycloviruses and gemycircularviruses are KJ831064, KP133075, KP151567, KP133076-KP133080

Competing interests None for all authors

References

- Blinkova O, Rosario K, Li L, Kapoor A, Slikas B, Bernardin F, Breitbart M, Delwart E. Frequent detection of highly diverse variants of cardiovirus, cosavirus, bocavirus, and circovirus in sewage samples collected in the United States. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2009;47:3507–3513. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01062-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucardo F, Reyes Y, Svensson L, Nordgren J. Predominance of norovirus and sapovirus in Nicaragua after implementation of universal rotavirus vaccination. PloS one. 2014;9:e98201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DK, Poon LL, Chiu SS, Chan KH, Ng EM, Bauer I, Cheung TK, Ng IH, Guan Y, Wang D, Peiris JS. Characterization of a novel gyrovirus in human stool and chicken meat. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2012;55:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JR, Caceres P, Cano F, Flores J, Bartlett A, Torun B. Adenovirus types 40 and 41 and rotaviruses associated with diarrhea in children from Guatemala. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1990;28:1780–1784. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.8.1780-1784.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesi P, Furnari C, Granato A, Schivo A, Otranto D, Capelli G, Cafarchia C. Molecular identity and prevalence of Cryptococcus spp. nasal carriage in asymptomatic feral cats in Italy. Medical mycology. 2014;52:667–673. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myu030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayaram A, Opong A, Jaschke A, Hadfield J, Baschiera M, Dobson RC, Offei SK, Shepherd DN, Martin DP, Varsani A. Molecular characterisation of a novel cassava associated circular ssDNA virus. Virus research. 2012;166:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayaram A, Potter KA, Moline AB, Rosenstein DD, Marinov M, Thomas JE, Breitbart M, Rosario K, Arguello-Astorga GR, Varsani A. High global diversity of cycloviruses amongst dragonflies. The Journal of general virology. 2013;94:1827–1840. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.052654-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayaram A, Potter KA, Pailes R, Marinov M, Rosenstein DD, Varsani A. Identification of diverse circular single-stranded DNA viruses in adult dragonflies and damselflies (Insecta: Odonata) of Arizona and Oklahoma, USA. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2015;30:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwart E, Li L. Rapidly expanding genetic diversity and host range of the Circoviridae viral family and other Rep encoding small circular ssDNA genomes. Virus research. 2012;164:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson EF, Haskew AN, Gates JE, Huynh J, Moore CJ, Frieman MB. Metagenomic analysis of the viromes of three North American bat species: viral diversity among different bat species that share a common habitat. Journal of virology. 2010;84:13004–13018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01255-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom J, Muhr LS, Bzhalava D, Soderlund-Strand A, Hultin E, Nordin P, Stenquist B, Paoli J, Forslund O, Dillner J. Diversity of human papillomaviruses in skin lesions. Virology. 2013;447:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer C, Colom F, Frases S, Mulet E, Abad JL, Alio JL. Detection and identification of fungal pathogens by PCR and by ITS2 and 5.8S ribosomal DNA typing in ocular infections. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2001;39:2873–2879. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2873-2879.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulongne V, Sauvage V, Hebert C, Dereure O, Cheval J, Gouilh MA, Pariente K, Segondy M, Burguiere A, Manuguerra JC, Caro V, Eloit M. Human skin microbiota: high diversity of DNA viruses identified on the human skin by high throughput sequencing. PloS one. 2012;7:e38499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo G, Ruiz-Moyano S, Hernandez A, Benito MJ, Cordoba MG, Perez-Nevado F, Martin A. Application of ISSR-PCR for rapid strain typing of Debaryomyces hansenii isolated from dry-cured Iberian ham. Food microbiology. 2014;42:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garigliany MM, Borstler J, Jost H, Badusche M, Desmecht D, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Cadar D. Characterization of a novel circo-like virus in Aedes vexans mosquitoes from Germany: evidence for a new genus within the Circoviridae family. The Journal of general virology. 2014 doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Li J, Peng C, Wu L, Yang X, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Shi Z. Genetic diversity of novel circular ssDNA viruses in bats in China. The Journal of general virology. 2011;92:2646–2653. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Li Y, Yang X, Zhang H, Zhou P, Zhang Y, Shi Z. Metagenomic analysis of viruses from bat fecal samples reveals many novel viruses in insectivorous bats in China. Journal of virology. 2012;86:4620–4630. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06671-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan GD, Grice EA. Microbial ecology of the skin in the era of metagenomics and molecular microbiology. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2013;3:a015362. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraberger S, Arguello-Astorga GR, Greenfield LG, Galilee C, Law D, Martin DP, Varsani A. Characterisation of a diverse range of circular replication-associated protein encoding DNA viruses recovered from a sewage treatment oxidation pond. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2015;31C:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberto I, Gunst K, Muller H, Zur Hausen H, de Villiers EM. Mycovirus-like DNA virus sequences from cattle serum and human brain and serum samples from multiple sclerosis patients. Genome announcements. 2014;2 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00848-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le VT, de Jong MD, Nguyen VK, Nguyen VT, Taylor W, Wertheim HF, van der Ende A, van der Hoek L, Canuti M, Crusat M, Sona S, Nguyen HU, Giri A, Nguyen TT, Ho DT, Farrar J, Bryant JE, Tran TH, Nguyen VV, van Doorn HR. Limited geographic distribution of the novel cyclovirus CyCV-VN. Scientific reports. 2014;4:3967. doi: 10.1038/srep03967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Kapoor A, Slikas B, Bamidele OS, Wang C, Shaukat S, Masroor MA, Wilson ML, Ndjango JB, Peeters M, Gross-Camp ND, Muller MN, Hahn BH, Wolfe ND, Triki H, Bartkus J, Zaidi SZ, Delwart E. Multiple diverse circoviruses infect farm animals and are commonly found in human and chimpanzee feces. Journal of virology. 2010a;84:1674–1682. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02109-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, McGraw S, Zhu K, Leutenegger CM, Marks SL, Kubiski S, Gaffney P, Dela Cruz FN, Jr., Wang C, Delwart E, Pesavento PA. Circovirus in tissues of dogs with vasculitis and hemorrhage. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013;19:534–541. doi: 10.3201/eid1904.121390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Shan T, Soji OB, Alam MM, Kunz TH, Zaidi SZ, Delwart E. Possible cross-species transmission of circoviruses and cycloviruses among farm animals. The Journal of general virology. 2011;92:768–772. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.028704-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Victoria JG, Wang C, Jones M, Fellers GM, Kunz TH, Delwart E. Bat guano virome: predominance of dietary viruses from insects and plants plus novel mammalian viruses. Journal of virology. 2010b;84:6955–6965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00501-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima FE, Cibulski SP, Dos Santos HF, Teixeira TF, Varela AP, Roehe PM, Delwart E, Franco AC. Genomic Characterization of Novel Circular ssDNA Viruses from Insectivorous Bats in Southern Brazil. PloS one. 2015;10:e0118070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londono A, Riego-Ruiz L, Arguello-Astorga GR. DNA-binding specificity determinants of replication proteins encoded by eukaryotic ssDNA viruses are adjacent to widely separated RCR conserved motifs. Archives of virology. 2010;155:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes MJ, Belloch C, Galiana M, Garcia MD, Andres C, Ferrer S, Torres-Rodriguez JM, Guinea J. Polyphasic taxonomy of a novel yeast isolated from antarctic environment; description of Cryptococcus victoriae sp. nov. Systematic and applied microbiology. 1999;22:97–105. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori D, Ranawaka U, Yamada K, Rajindrajith S, Miya K, Perera HK, Matsumoto T, Dassanayake M, Mitui MT, Mori H, Nishizono A, Soderlund-Venermo M, Ahmed K. Human bocavirus in patients with encephalitis, Sri Lanka, 2009-2010. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013;19:1859–1862. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.121548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TF, Marine R, Wang C, Simmonds P, Kapusinszky B, Bodhidatta L, Oderinde BS, Wommack KE, Delwart E. High variety of known and new RNA and DNA viruses of diverse origins in untreated sewage. Journal of virology. 2012;86:12161–12175. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00869-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TF, Willner DL, Lim YW, Schmieder R, Chau B, Nilsson C, Anthony S, Ruan Y, Rohwer F, Breitbart M. Broad surveys of DNA viral diversity obtained through viral metagenomics of mosquitoes. PloS one. 2011;6:e20579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Rodriguez M, Rosario K, Breitbart M. Novel cyclovirus discovered in the Florida woods cockroach Eurycotis floridana (Walker) Archives of virology. 2013;158:1389–1392. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1606-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan TG, Li L, O’Ryan MG, Cortes H, Mamani N, Bonkoungou IJ, Wang C, Leutenegger CM, Delwart E. A third gyrovirus species in human faeces. The Journal of general virology. 2012;93:1356–1361. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.041731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan TG, Luchsinger V, Avendano LF, Deng X, Delwart E. Cyclovirus in nasopharyngeal aspirates of Chilean children with respiratory infections. The Journal of general virology. 2014;95:922–927. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.061143-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter G, Pankovics P, Gyongyi Z, Delwart E, Boros A. Novel dicistrovirus from bat guano. Archives of virology. 2014;159:3453–3456. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario K, Dayaram A, Marinov M, Ware J, Kraberger S, Stainton D, Breitbart M, Varsani A. Diverse circular ssDNA viruses discovered in dragonflies (Odonata: Epiprocta) The Journal of general virology. 2012a;93:2668–2681. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.045948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario K, Duffy S, Breitbart M. A field guide to eukaryotic circular single-stranded DNA viruses: insights gained from metagenomics. Archives of virology. 2012b;157:1851–1871. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1391-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario K, Marinov M, Stainton D, Kraberger S, Wiltshire EJ, Collings DA, Walters M, Martin DP, Breitbart M, Varsani A. Dragonfly cyclovirus, a novel single-stranded DNA virus discovered in dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera) The Journal of general virology. 2011;92:1302–1308. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.030338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular biology and evolution. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage V, Cheval J, Foulongne V, Gouilh MA, Pariente K, Manuguerra JC, Richardson J, Dereure O, Lecuit M, Burguiere A, Caro V, Eloit M. Identification of the first human gyrovirus, a virus related to chicken anemia virus. Journal of virology. 2011;85:7948–7950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00639-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schowalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, Moyer AL, Buck CB. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell host & microbe. 2010;7:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sdiri-Loulizi K, Gharbi-Khelifi H, de Rougemont A, Chouchane S, Sakly N, Ambert-Balay K, Hassine M, Guediche MN, Aouni M, Pothier P. Acute infantile gastroenteritis associated with human enteric viruses in Tunisia. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2008;46:1349–1355. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02438-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sdiri-Loulizi K, Gharbi-Khelifi H, de Rougemont A, Hassine M, Chouchane S, Sakly N, Pothier P, Guediche MN, Aouni M, Ambert-Balay K. Molecular epidemiology of human astrovirus and adenovirus serotypes 40/41 strains related to acute diarrhea in Tunisian children. Journal of medical virology. 2009;81:1895–1902. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski A, Massaro M, Kraberger S, Young LM, Smalley D, Martin DP, Varsani A. Novel myco-like DNA viruses discovered in the faecal matter of various animals. Virus research. 2013;177:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits SL, Zijlstra EE, van Hellemond JJ, Schapendonk CM, Bodewes R, Schurch AC, Haagmans BL, Osterhaus AD. Novel cyclovirus in human cerebrospinal fluid, Malawi, 2010-2011. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013;19 doi: 10.3201/eid1909.130404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular biology and evolution. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan le V, van Doorn HR, Nghia HD, Chau TT, Tu le TP, de Vries M, Canuti M, Deijs M, Jebbink MF, Baker S, Bryant JE, Tham NT, NT BK, Boni MF, Loi TQ, Phuong le T, Verhoeven JT, Crusat M, Jeeninga RE, Schultsz C, Chau NV, Hien TT, van der Hoek L, Farrar J, de Jong MD. Identification of a new cyclovirus in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with acute central nervous system infections. mBio. 2013;4:e00231–00213. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00231-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd D. Avian circovirus diseases: lessons for the study of PMWS. Veterinary microbiology. 2004;98:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd D, McNulty MS, Adair BM, Allan GM. Animal circoviruses. Advances in virus research. 2001;57:1–70. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(01)57000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brand JM, van Leeuwen M, Schapendonk CM, Simon JH, Haagmans BL, Osterhaus AD, Smits SL. Metagenomic analysis of the viral flora of pine marten and European badger feces. Journal of virology. 2012;86:2360–2365. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06373-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley C, Gunst K, Muller H, Funk M, Zur Hausen H, de Villiers EM. Novel replication-competent circular DNA molecules from healthy cattle serum and milk and multiple sclerosis-affected human brain tissue. Genome announcements. 2014;2 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00849-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whon TW, Kim MS, Roh SW, Shin NR, Lee HW, Bae JW. Metagenomic characterization of airborne viral DNA diversity in the near-surface atmosphere. Journal of virology. 2012;86:8221–8231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00293-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Li B, Fu Y, Jiang D, Ghabrial SA, Li G, Peng Y, Xie J, Cheng J, Huang J, Yi X. A geminivirus-related DNA mycovirus that confers hypovirulence to a plant pathogenic fungus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:8387–8392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913535107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]