Abstract

Research on delay discounting has focused largely on non-drug reinforcers in an isomorphic context in which choice is between alternatives that involve the same type of reinforcer. Less often, delay discounting has been studied with drug reinforcers in a more ecologically valid allomorphic context where choice is between alternatives involving different types of reinforcers. The present experiment is the first to examine discounting of drug and non-drug reinforcers in both isomorphic and allomorphic situations using a theoretical model (i.e., the hyperbolic discounting function) that allows for comparisons of discounting rates between reinforcer types and amounts. The goal of the current experiment was to examine discounting of a delayed, non-drug reinforcer (food) by male rhesus monkeys when the immediate alternative was either food (isomorphic situation) or cocaine (allomorphic situation). In addition, we sought to determine whether there was a magnitude effect with delayed food in the allomorphic situation. Choice of immediate food and immediate cocaine increased with amount and dose, respectively. Choice functions for immediate food and cocaine generally shifted leftward as delay increased. Compared to isomorphic situations in which food was the immediate alternative, delayed food was discounted more steeply in allomorphic situations where cocaine was the immediate alternative. Notably, discounting was not affected by the magnitude of the delayed reinforcer. These data indicate that how steeply a delayed non-drug reinforcer is discounted may depend more on the qualitative characteristics of the immediate reinforcer and less on the magnitude of the delayed one.

Keywords: Choice, Cocaine, Delay Discounting, Food, Rhesus Monkey, Self-administration

Introduction

Introducing a delay between a behavior and its consequence decreases the rate at which that behavior occurs (for a review, see Lattal, 2010). Similarly, reinforcers lose their value as a hyperbolic function of the delay to their receipt, a phenomenon referred to as delay discounting (e.g., Mazur, 1987; Rachlin, Raineri, and Cross, 1991). In delay-discounting procedures, human and nonhuman animals are given choices between reinforcers that vary in amount and delay, and the decrease in the value of a reinforcer as the delay until its delivery increases is well described by the hyperboloid discounting function (for a review, see Green and Myerson, 2004),

| (1) |

where V is the present value of the delayed alternative, A is the magnitude of the delayed alternative, k is a parameter that reflects the rate of discounting, and D is the delay to reinforcer delivery. The scaling parameter s often is unnecessary for describing choice by nonhuman animals (i.e., s = 1.0), in which case Eq. 1 reduces to a simple hyperbola (Mazur, 1987). A steeper rate of discounting (larger k) has been characterized as impulsive because it reflects more choice of the smaller, sooner reinforcer, whereas a shallower rate has been characterized as self-controlled because it reflects more choice of the larger, later reinforcer.

In humans, there is consistent evidence of a magnitude effect in which larger-magnitude delayed reinforcers are discounted less steeply than smaller-magnitude delayed reinforcers (e.g., Green, Myerson, and McFadden, 1997). This effect has been obtained with numerous reinforcers, both hypothetical and actual, and most robustly with delayed monetary outcomes (e.g., Baker, Johnson, and Bickel, 2003; Estle, Green, Myerson, and Holt, 2007; Giordano, Bickel, Loewenstein, Jacobs, Marsch, Badger, 2002; Green, Myerson, and Ostaszewski, 1999; Jimura, Myerson, Hilgard, Braver, and Green, 2009; Johnson and Bickel, 2002; Kirby, 1997; Kirby and Marakovic, 1996; Odum, Baumann, and Rimington, 2006; Petry, 2001). Notably, magnitude effects have been observed in humans with comparisons ranging from as little as a two-fold difference in the amounts of the delayed outcomes to as much as a ten-fold difference (e.g., Estle et al., 2007; Giordano et al., 2002; Jimura et al., 2009; Kirby 1997). Conversely, little evidence of a magnitude effect exists in nonhuman subjects. Magnitude effects were not obtained in rats or pigeons with liquid reinforcers or with food reinforcers using amounts that differed by 1.5- to 6.4-fold (Grace, 1999; Green, Myerson, Holt, Slevin, and Estle, 2004; Oliveira, Green, and Myerson, 2014; Richards, Mitchell, de Wit, and Seiden, 1997; cf. Grace, Sargisson, and White, 2012) or in rhesus monkeys with saccharin solutions or with sucrose solutions with delayed magnitudes that differed two-fold (Freeman, Green, Myerson, and Woolverton, 2009; Freeman, Nonnemacher, Green, Myerson, and Woolverton, 2012). Similarly, highly preferred food or liquids were not discounted less steeply than non-preferred food or liquids in rats, suggesting that qualitatively different reinforcers are discounted at the same rate (Calvert, Green, and Myerson, 2010). Taken together, these results suggest that discounting rate in nonhumans does not depend on the magnitude of the delayed reinforcer.

Delay discounting has become increasingly important for understanding several problematic behaviors, including drug abuse (for reviews, see Yi, Mitchell, and Bickel, 2010; Perry and Carroll, 2008). Many have conceptualized drug abuse as impulsive choice of more immediate drug effects over more delayed non-drug alternatives such as one’s health, employment, or interpersonal relationships (e.g., Yi et al., 2010). This idea is supported by the consistent finding that drug abusers discount hypothetical money and health outcomes more steeply than never- or ex-abusers and discount hypothetical drug more steeply than hypothetical money (e.g., Bickel, Odum, and Madden, 1999; Coffey, Gudleski, Saladin, and Brady, 2003; Madden, Petry, Badger, and Bickel, 1997; Vuchinich and Simpson, 1998). In addition, drug abusers with shallower discounting rates had better treatment outcomes than those with steeper rates, suggesting that discounting predicts treatment effectiveness and recidivism (Washio, Higgins, Heil, McKerchar, Badger, Skelly et al., 2011; Yoon, Higgins, Heil, Sugarbaker, Thomas, and Badger, 2007).

A relation between drug taking and delay discounting also has been observed in nonhuman subjects. Steeper discounting is associated with higher levels of cocaine, nicotine, and ethanol intake, faster acquisition and enhanced escalation of cocaine self-administration (Anker, Perry, Gliddon, and Carroll, 2009; Perry, Larson, German, Madden, and Carroll, 2005; Perry, Nelson, and Carroll, 2008; for a review, see Carroll, Anker, Mach, Newman, and Perry, 2010). Similarly, acute and chronic exposure to drugs of abuse can alter rate of discounting (for a review, see de Wit and Mitchell, 2010).

To date, most delay-discounting studies with nonhumans have examined effects of experimenter-administered drugs on delay discounting of food or liquid reinforcers, and fewer studies have examined discounting when at least one of the reinforcers was a drug (Anderson and Woolverton, 2003; Harvey-Lewis, Perdrizet, and Franklin, 2014; Maguire, Gerak, and France, 2013a; 2013b; Newman, Perry, and Carroll, 2008; Perry, Nelson, Anderson, Morgan, and Carroll, 2007; Woolverton and Anderson, 2006; Woolverton, Myerson, and Green, 2007). In most of these studies, choice was examined in isomorphic situations (i.e., choice between qualitatively identical reinforcers; Anderson and Woolverton, 2003; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2014; Maguire et al., 2013b; Newman et al., 2008; Perry et al., 2007; Woolverton et al., 2007). Because delay discounting has been conceptualized as impulsive choice of immediate drug effects, it is important to understand delay discounting of non-drug reinforcers when drugs are immediately available as a fundamental component of the drug abuse process. In humans, delay discounting in such allomorphic situations (i.e., choice between qualitatively different reinforcers) has been examined in relatively few studies (Bickel, Landes, Christensen, Jackson, Jones, Kurth-Nelson, et al., 2011; Mitchell, 2004; Yoon, Higgins, Bradstreet, Badger, and Thomas, 2009). In the most comprehensive examination, discounting of hypothetical money and cocaine was examined in all possible arrangements of isomorphic and allomorphic situations (Bickel et al., 2011). Discounting functions were steepest with immediate money versus delayed cocaine and were shallowest with immediate money versus delayed money, suggesting that discounting of hypothetical money or cocaine depends on both the choice situation (i.e., isomorphic versus allomorphic) and the type of reinforcers involved (i.e., drug versus non-drug). In two experiments with rhesus monkeys, delay discounting was examined under allomorphic conditions where choice was between food and cocaine (Woolverton and Anderson, 2006) or food and remifentanil (Maguire et al., 2013a). As expected, choice of the delayed alternative (i.e., food, cocaine, or remifentanil) decreased as the delay to its delivery increased.

Relatively little research on discounting of drug reinforcers in isomorphic or allomorphic situations with nonhuman animals was conducted within a hyperbolic framework (i.e., the data could not be or were not fit with a hyperbolic function). For this reason, it is not possible to compare the degree of discounting across reinforcers, across isomorphic and allomorphic situations, or across experiments. The exception is Woolverton et al. (2007) who investigated hyperbolic discounting of cocaine in an isomorphic situation. In this experiment, monkeys discounted delayed cocaine at a shallow rate relative to rates reported for non-drug reinforcers in rats or pigeons. Given that this was the first examination of hyperbolic discounting of a drug in any nonhuman species, it could not be determined whether the shallow discounting observed with cocaine was a consequence of the species, the reinforcer, or both. Subsequent work demonstrated that monkeys discounted saccharin and sucrose solutions at rates comparable to those reported with non-drug reinforcers in rodents and pigeons (Freeman et al., 2009; 2012), suggesting that discounting of non-drug reinforcers is similar across species and that the shallow discounting reported in Woolverton et al. was a consequence of the specific characteristics of cocaine and perhaps other drugs of abuse.

The primary goal of the current experiment was to examine discounting of a delayed, non-drug reinforcer (food) by male rhesus monkeys when the immediate alternative was either food (isomorphic situation) or cocaine (allomorphic situation). In addition, we sought to determine whether there was a magnitude effect with delayed food in the allomorphic situation. The hyperbolic discounting function was used to measure the degree of discounting to allow quantitative comparisons between the different conditions.

Method

All animal-use procedures were approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition, 2011).

Subjects and Apparatus

Eight male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) served as subjects. Five subjects (CK6R, M163, MR4324, M341, RO105) served in isomorphic (immediate food vs. delayed food) conditions and six (314116, DK1M, M163, MR4324, RO105, RQ6671) in allomorphic (immediate cocaine vs. delayed food) conditions. Three of these subjects (M163, MR4324, RO105) served in all conditions. Four subjects (314116, DK1M, MR4324, RQ661) were experimentally naïve at the beginning of the experiment. The other four subjects (CK6R, M163, M341, RO105) had experimental histories, most recently with ropinirole self-administration (CK6R; Freeman, Heal, McCreary, and Woolverton, 2012), delay discounting of sucrose solutions (M163 and RO105; Freeman et al., 2012), and delayed punishment of cocaine self-administration with histamine (M341; Woolverton, Freeman, Myerson, and Green, 2012). Subjects were given unlimited access to water and were maintained at stable body weights by food provided during the session as well as supplemental feeding (Teklad 25% Monkey Diet, Harlan/Teklad, Madison, WI). Subject weights ranged from 8.2–11.5 kg at the beginning of the experiment. Fresh fruit and forage (e.g., dried fruit and nuts) were provided daily, and a multivitamin was given three times per week. Lights were maintained on a 16/8-h light/dark cycle, with lights on at 0600 h.

Monkeys were fitted with a mesh jacket and tether (Lomir Biomedical, Malone, NY) that attached to the rear wall of the experimental cubicle (1.0 m3, Plaslabs, Lansing, MI). A single response lever (custom designed and fabricated) was mounted inside the door of the cubicle. This manipulandum can be conceptualized as a joystick restricted to a horizontal range of motion such that responses to the left or right result in two different consequences (analogous to the two-lever arrangement typically used in operant choice experiments). Four jeweled stimulus lights (two white and two red) were aligned vertically to the left and right sides of the response lever. A feeder was mounted on the outside of the cubicle door and delivered 1-g very berry pellets (Bio-Serv) at a rate of one pellet per 0.5 s. Drug infusions lasted 10 s and were delivered by a peristaltic infusion pump (Cole-Parmer, Chicago, IL). A Macintosh computer with custom interface and software controlled experimental events and recorded data.

Surgery

For allomorphic (cocaine vs. food) conditions, each monkey had a single lumen intravenous catheter implanted according to previously published protocols (e.g., Freeman, Wang, and Woolverton, 2010). Monkeys were given atropine sulfate (0.04 mg/kg, i.m.) and ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg, i.m.) followed by inhaled isoflurane. The catheter was implanted into a major vein with the tip terminating near the right atrium. The distal end of the catheter was passed subcutaneously to the mid-scapular region, where it exited the subject’s back and was then threaded through a tether, connected to a single-lumen swivel (Lomir Biomedical, Inc., Malone, NY) and then to an infusion pump outside the cubicle. A chewable antibiotic (Kefzol; Eli Lilly & Company, Indianapolis, IN) was administered (22.2 mg/kg) twice daily for seven days to prevent infection. If a catheter became nonfunctional, it was removed, and the monkey was removed from the experiment for 1–2 weeks. After good health was verified, a new catheter was implanted. The catheter was filled with 40 units/ml heparinized-saline between sessions to prevent clotting at the catheter tip.

Procedure

The procedure was similar to previous delay-discounting studies from our laboratory (Freeman et al., 2009; 2012; Woolverton et al., 2007). Sessions were conducted daily, beginning at 12:00 p.m., and were signaled by illumination of the white lights to the left or right of the response lever. In isomorphic (food vs. food) conditions, one side was associated with an immediate amount of food that was systematically varied between 1–8 pellets/delivery and the other side with a delayed amount of food that remained fixed at 4 pellets/delivery. In allomorphic (cocaine vs. food) conditions, one side was associated with a 10-s injection of cocaine that was systematically varied between 0.003–0.4 mg/kg/injection delivered immediately and the other side with a fixed amount of food (4 or 8 pellets depending on the condition) delivered after a delay.

Sessions began with four sample trials with one active side (left or right) signaled by illumination of the corresponding set of white lever lights, and the consequence associated with the active side of the lever was available. The active side was randomly determined at the start of each session and alternated between sides for subsequent sample trials. Sample trials were followed by 16 choice trials. During choice trials, both sets of white lever lights were illuminated, both sides of the lever were active, and consequences associated with both sides were available. Two subjects (CK6R and M341) started the isomorphic condition with four sample and 16 choice trials, but the number of trials was reduced to two sample and eight choice trials because these subjects were either receiving more than their daily ration of food during sessions or were not finishing sessions with more trials.

For all trials, five consecutive lever presses to one side (FR 5) had to occur to result in the cocaine or food associated with that side. Responses to either side reset the FR contingency on the opposite side. Following completion of the FR 5 on one side, the corresponding set of white lights was darkened. If a delay was programmed, the red lights on the side that was pressed flashed for the duration of the delay. After the delay, or after completion of the FR 5 when the delay was 0 s, the red lights remained illuminated for 10 s during the cocaine injection or delivery of food pellets, depending on which side was pressed. After cocaine or food delivery, all lever lights were darkened during the remainder of the timeout. The timeout was always 30 min, and the delay, followed by reinforcer delivery, operated concurrently with the timeout to ensure that trials always began 30 min after completion of the previous trial and that reinforcement rate did not co-vary with delay. Responses during the delay, reinforcer delivery, and timeout were recorded but had no programmed consequences.

Choice functions were established in isomorphic conditions with an immediate amount of food (1–8 pellets/delivery) as the consequence associated with one side of the lever and four delayed (0–120 s) food pellets as the consequence associated with the other side. In allomorphic conditions, dose-response functions were established with an immediate dose of cocaine (0.003–0.4 mg/kg/injection) as the consequence associated with one side of the lever and either four or eight delayed (0–120 s) food pellets as the consequence associated with the other side. Thus, one magnitude (4 pellets) of delayed food was examined in isomorphic conditions, and two magnitudes (4 and 8 pellets) of delayed food were examined in allomorphic conditions.

The order in which isomorphic and allomorphic conditions were conducted was counterbalanced between monkeys, and cocaine doses and food magnitudes were examined in an irregular order within and between monkeys (i.e., the doses and food amounts were not presented in ascending or descending order). Each choice condition was in effect until choice was stable according to the following criteria: 1) completion of all sample and choice trials, 2) the number of reinforcers delivered on one side was within 20% of the three-session mean for three consecutive sessions, and 3) there were no upward or downward trends across the three sessions. Once stability was achieved, the cocaine or food alternative associated with each side of the lever was reversed, and stable choice was re-determined.

Data Analysis

In all conditions, the mean choice data from the last three sessions of each food- or injection-lever pairing and its reversal were plotted as percent choice of the immediate alternative as a function of the amount (food) or dose (cocaine) of the immediate alternative. A separate choice function was plotted for each delay with the goal of obtaining complete functions with choices that ranged from less than 20% to greater than 80%. In a small number of cases, this was not feasible because the smallest amount of food or smallest dose of cocaine possible resulted in greater than 20% immediate choice.

Indifference points were calculated based on each choice function (i.e., the amount or dose of the immediate alternative that predicted 50% choice between the immediate and delayed alternatives) by log-transforming the x-axis and using a best-fitting logistic function (GraphPad Software 6.0). To facilitate comparisons across conditions, indifference points were normalized by dividing each indifference point by the indifference point obtained when both alternatives were delivered immediately and multiplying by 100 to obtain percentages. Normalized indifference points then were plotted as a function of delay and a simple hyperbola (Eq. 1 with s=1.0) was fit to the indifference points. Because the indifference points were normalized as percentages, A was set at 100.

Median hyperbolic discounting curves and k values were compared across conditions to determine the following: 1) whether four pellets of delayed food were discounted differently across isomorphic (immediate food vs. delayed food) and allomorphic (immediate cocaine vs. delayed food) conditions, and 2) whether four or eight delayed food pellets were discounted differently in the allomorphic situation (i.e., whether there was a magnitude effect in this situation). Because the error variance in k values was significantly different in different conditions, and because not all subjects experienced every condition, an unpaired Mann-Whitney test was used to compare k values from the isomorphic condition relative to the allomorphic conditions. Because the same subjects experienced both allomorphic conditions, a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was used to compare k values for each allomorphic condition.

Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rockville, MD). Final solutions were prepared using 0.9% saline. Doses are expressed as the salt forms of the drugs.

Results

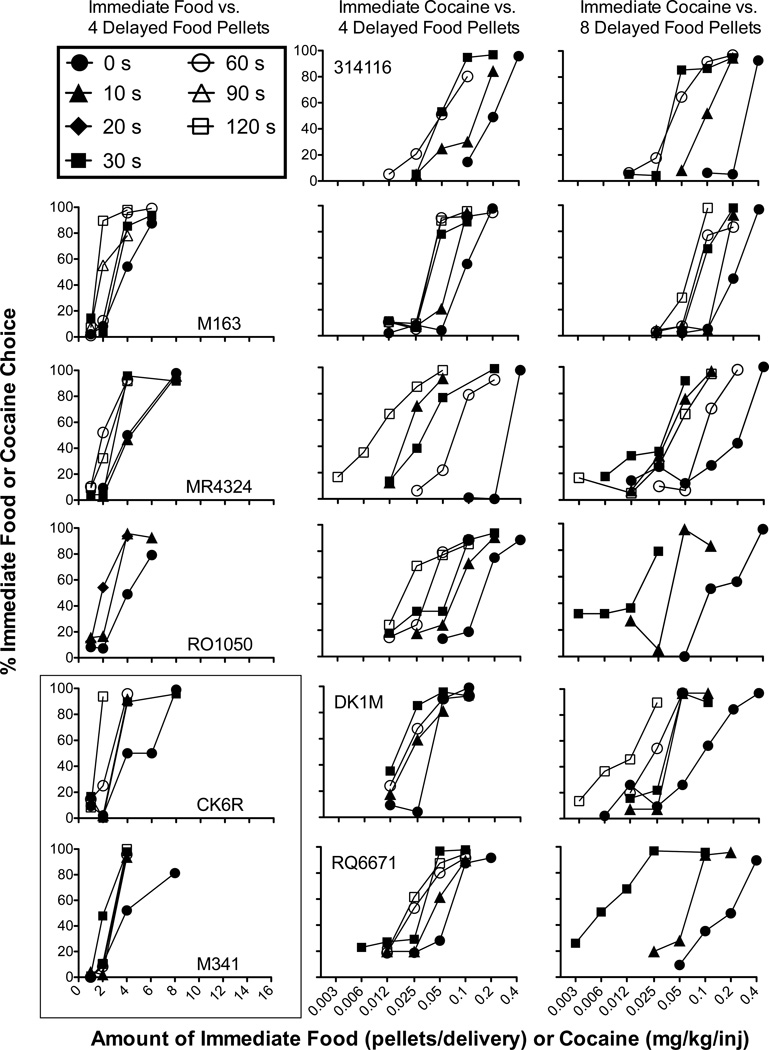

Figure 1 shows choice functions obtained for individual monkeys in the isomorphic condition in which choice was between immediate food and four delayed food pellets (left column) and in the allomorphic conditions in which choice was between immediate cocaine and either four (middle column) or eight delayed food pellets (right column). Across subjects and conditions, the mean number of sessions to reach stability was 6.2 (range = 5.2–8.2) in the initial food- or injection-lever pairing, and 6.1 (range = 5.1–7.9) in the reversal. In general, choice of the immediate alternative was an increasing function of the amount or dose of the immediate alternative. This general pattern was observed across individual subjects and delays in all three conditions. As expected, the mean indifference point at the 0-s delay in the isomorphic condition was similar to the fixed four-pellet alternative (M = 4.09, SEM = 0.13), indicating that 4.1 food pellets were functionally equivalent to four food pellets. In allomorphic conditions, the mean indifference points at the 0-s delay were 0.15 (SEM = 0.05) and 0.23 (SEM = 0.04) for four and eight food pellets, respectively, indicating that a smaller dose (i.e., 0.15 mg/kg/inj) was functionally equivalent to four food pellets and a larger dose (i.e., 0.23 mg/kg/inj) was functionally equivalent to eight food pellets. As the delay to the food alternative was increased, choice functions shifted to the left. That is, progressively smaller amounts or doses of the immediate alternative were chosen over the delayed food alternative, although there were some exceptions to this general pattern (i.e., subject MR4324 in all three conditions, DK1M with immediate cocaine versus four delayed food pellets, and M341 with immediate food versus four delayed food pellets).

Figure 1.

Mean percent choice for the alternative associated with immediate food (left column) or immediate cocaine (middle and right columns) delivery as a function of the immediate amount of food (1–8 pellets/delivery; left column) or cocaine (0.003–0.4 mg/kg/inj; middle and right columns). The delayed amount of food was four pellets per delivery in the left and middle columns and was 8 pellets per delivery in the right column. Each data point is the average of the initial-lever pairing and its reversal, and each choice function represents a different delay (0–120 s) to the four- or eight-pellet alternatives. The rectangle in the bottom left corner indicates two subjects (CK6R and M341) that only experienced food-vs-food conditions. Other panels show the same subject from left to right across columns.

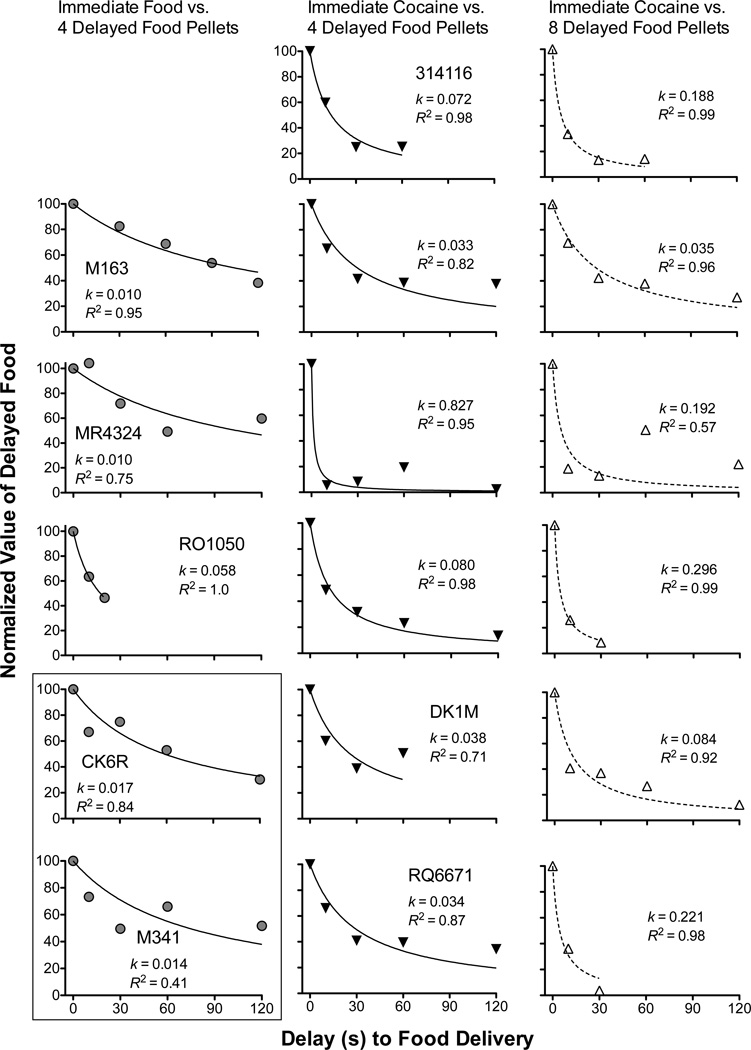

Figure 2 shows the normalized indifference points obtained from the choice functions in Figure 1, plotted as a function of the time until delivery of the delayed food reinforcer. Each indifference point reflects the amount or dose of the immediate alternative whose normalized value is approximately that of the delayed food alternative. As the delay to the four- or eight-pellet alternative increased, indifference points decreased (i.e., value of the delayed reinforcer was a decreasing function of delay to its receipt). Overall, the data were fairly well described by a simple hyperbola (mean R2 = .86, median R2 = .95, range R2 = .41–1.0). In 15 of 17 cases, R2 values were above 0.70. The two cases in which fits were poor were M341 in the isomorphic situation when choice was between immediate food and four delayed food pellets and MR4324 in the allomorphic situation when choice was between immediate cocaine and eight delayed food pellets.

Figure 2.

Normalized value of delayed food pellets as a function of the delay (0–120 s) to food delivery when choice was between immediate food (1–8 pellets/delivery) and four delayed food pellets (left panels), when choice was between immediate cocaine (0.003–0.4 mg/kg/inj) and four (middle panels) or eight (right panels) delayed food pellets. Each panel shows k and R2 values for individual subjects in each condition. The rectangle in the bottom left corner indicates two subjects (CK6R and M341) that only completed food-vs-food conditions. Other panels show the same subject from left to right across columns.

Figure 2 also presents the k values for each individual subject in each condition. As may be seen in the Figure, the same delayed reinforcer (four food pellets) was discounted at a different rate depending on the immediate alternative (i.e., food or cocaine). In fact, regardless of whether the delayed reinforcer was four or eight food pellets, the rate of discounting in the isomorphic condition (left column) differed significantly from that in the allomorphic conditions (middle and right columns) [Mann-Whitney U = 3.0, n1 = 5, n2 = 6, p < 0.05; U = 1.0, n1 = 5, n2 = 6, p < 0.05, respectively], reflecting the fact that discounting tended to be shallower in the isomorphic condition. With respect to the two allomorphic conditions, the median k values between the four- and eight-pellet conditions were not statistically different [Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, W = −9.0, p = 0.4], suggesting that discounting of delayed food pellets in an allomorphic situation does not depend on the size of the delayed reinforcer. It is important to note that even though four and eight food pellets were not discounted at different rates, subjects could discriminate between these two amounts. Figure 1 (left panels) shows that eight pellets was consistently chosen over four pellets (>80%), and for two subjects (M163 and RO1050), six pellets was consistently chosen over four pellets.

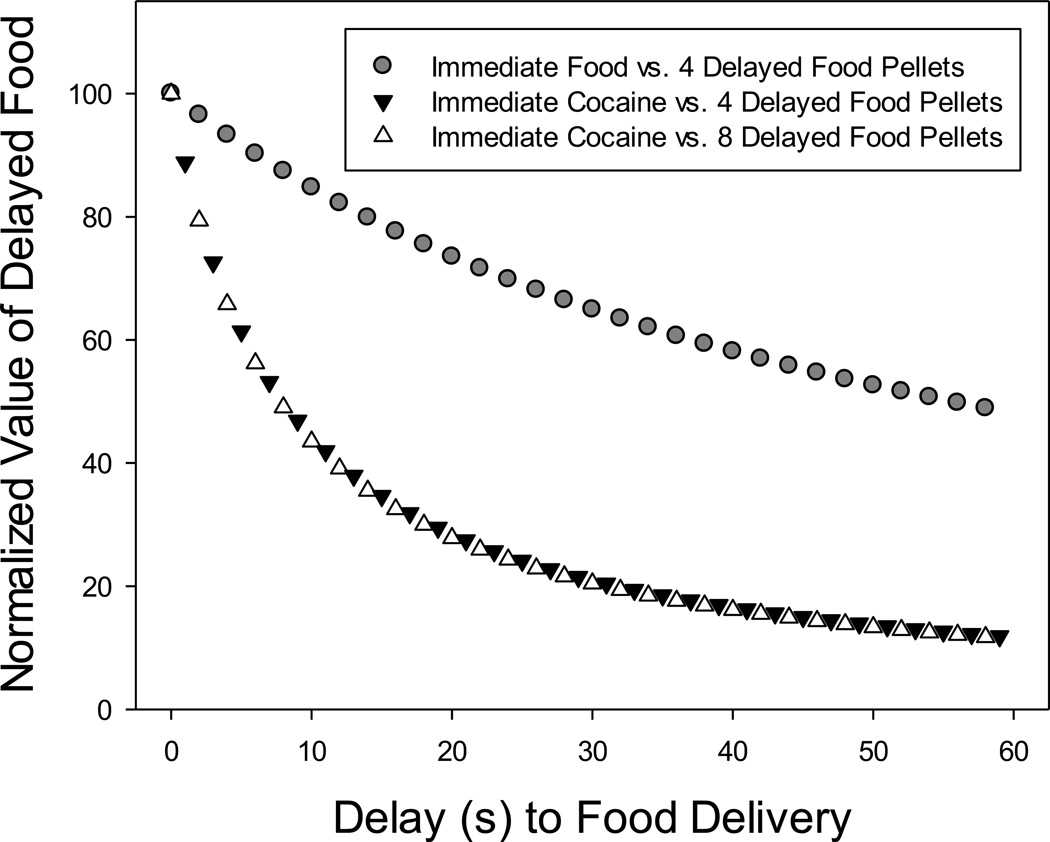

Figure 3 presents the average discounting curve for the three subjects (M163, MR4324, and RO1050) that were exposed to each of the three conditions: the isomorphic condition (immediate vs. delayed food), and the two allomorphic conditions (immediate cocaine vs. 4 and 8 delayed food pellets). For each condition, we determined the average k value by calculating the logarithm of the estimated value of k for each of the three subjects, taking the mean of these log k values, and then calculating the antilog of the mean log k. For the isomorphic and each allomorphic condition, we then substituted the average k for that condition into the equation for a simple hyperbola (Eq. 1 with s=1.0) and plotted the predicted values of V. Because one subject was not exposed to the longer delays in all three conditions, D was varied from 0 to 60 in order to minimize the amount of extrapolation involved in calculating the average curves. Consistent with the results of the analyses reported above for Figure 2, Figure 3 illustrates that discounting was much shallower in the isomorphic condition than in the allomorphic conditions, the latter of which differed little if at all in the degree to which they were discounted. Simply stated, the conclusions are strengthened by the fact that differences in discounting rates between the isomorphic and allomorphic conditions were also evident in a within-subjects comparison of three monkeys that were exposed to all three conditions.

Figure 3.

Average normalized values of delayed food pellets as a function of the delay to food delivery for the three monkeys (M163, MR4324, and RO1050) that were tested in all three conditions. The symbols represent the predictions of the average discounting function for each condition (see text for details).

Discussion

Consistent with previous research, the value of delayed food decreased as a function of the time until its delivery, and discounting functions for delayed food were generally well described by the hyperbolic equation (e.g., Mazur, 1987; Richards et al., 1997). The major new finding in the current experiment was that the rate of discounting of delayed food was steeper when cocaine was the immediate alternative (i.e., allomorphic choice) than when food was the immediate alternative (i.e., isomorphic choice). Another new finding was that the magnitude of the delayed reinforcer did not systematically affect discounting in the allomorphic situation even though the magnitudes of the delayed alternative in each allomorphic situation were functionally distinct and discriminable. It is possible that a larger difference between the delayed magnitudes would have resulted in a magnitude effect. However, magnitude effects with non-drug reinforcers have not been observed in isomorphic situations with as large as a 6.4-fold difference in the amounts of the delayed reinforcers (e.g., Green et al., 2004).

A likely explanation for the steeper rate of discounting in the allomorphic situation is that cocaine was a more effective reinforcer than food for these subjects. Animals in the current study switched from the delayed food alternative to the immediate cocaine alternative at shorter delays relative to immediate food. The idea that cocaine is a more effective reinforcer than food (at least within the context of delay discounting) also is supported by results obtained in isomorphic situations in which cocaine was discounted at a shallower rate than food, sucrose, or saccharin (current study; Freeman et al., 2009; 2012, Woolverton et al., 2007). In other words, rhesus monkeys will tolerate much longer delays when choice is maintained by cocaine injections relative to other non-drug reinforcers. The next step will be to examine delay discounting in an allomorphic situation in which choice is between immediate food and delayed cocaine. If cocaine is a more effective reinforcer than other non-drug alternatives, one would predict relatively shallow discounting when cocaine is the delayed reinforcer and food is the immediate reinforcer compared to when food is the delayed reinforcer and cocaine is the immediate reinforcer, as in the current experiment.

Another potential explanation that could account for the steeper rate of discounting in the allomorphic situation relative to the isomorphic situation includes the possibility that the degree of discounting is influenced by the degree to which the available alternatives are economic substitutes. It may be that perfect substitutes, as in the isomorphic situation, are discounted at a shallower rate, whereas less perfect substitutes, like those in the allomorphic situations, are discounted more rapidly. If this were the case, however, one would expect that the isomorphic condition with food in the current experiment would produce rates of discounting similar to those observed with other reinforcers (e.g., cocaine) in isomorphic conditions. Although this comparison has not been made using a within-subject design, the discounting rates for cocaine (indicated by k values) in Woolverton et al. (2007) in an isomorphic situation tended to be slightly more shallow (median k = 0.008) than the rates obtained in the current study with food in an isomorphic condition (median k = 0.014). Additional research would need to be conducted to determine whether economic substitutability is an important determinant of the rate of delay discounting.

Cocaine is known to be an appetite suppressant. Thus, it also is possible that the different rates of discounting across isomorphic and allomorphic conditions occurred because cocaine decreased the reinforcing effectiveness of food in the allomorphic situation. However, Negus and Mello (2003a; 2003b) have shown that chronic administration of d-amphetamine, a stimulant with similar appetite-suppressing effects, only transiently reduced food-maintained responding in monkeys under a second-order schedule (for approximately 9 days) and did not significantly reduce break points for food under a progressive-ratio schedule. Further, animals in the current study received daily choices between cocaine and food for several months, likely reducing any appetite suppression that might occur with acute exposure to a CNS stimulant. Finally, the current study used 30-min timeouts between choice trials to reduce indirect effects of the drug, including appetite suppression and motoric disruption, on each choice. In future experiments, one direct test of the role of appetite suppression would be to manipulate the timeout duration. If cocaine were decreasing the reinforcing effectiveness of food, one would expect steeper rates of discounting with shorter timeouts that allow for more drug accumulation across the session and shallower rates with longer timeouts that reduce the amount of drug accumulation across the session.

It is important to note that both the hypothesis that cocaine is discounted at a shallower rate than non-drug reinforcers in rhesus monkeys, and the current finding that delayed food is discounted more steeply when cocaine is the immediate alternative, are in contrast to studies conducted with drug-dependent humans in which a hypothetical drug was discounted more steeply than hypothetical money (i.e., a non-drug reinforcer; e.g., Coffey et al., 2003; Madden et al., 1997). In addition, Bickel and colleagues (2011) reported that when the immediate alternative was hypothetical money, delayed hypothetical cocaine was discounted more steeply than in the opposite situation with immediate hypothetical cocaine versus delayed hypothetical money. This is opposite of what one might expect based on results from the current experiment.

There are several procedural differences that may account for the discrepancy between the results obtained with drug-dependent humans and those observed in the present experiment. First, an advantage of the current study was that cocaine and food were actually delivered to the subjects. With human participants, hypothetical outcomes are typically presented, and it is not known whether human participants would discount actual cocaine deliveries at rates similar to hypothetical cocaine deliveries. In addition, delay discounting of cocaine by human participants has not been examined in an allomorphic situation in which the choice is between cocaine and a consumable non-drug reinforcer. While drug, food, and liquid reinforcers are consumable, money is not. In nondrug-dependent individuals, hypothetical food is discounted more steeply than equivalent amounts of hypothetical money (e.g., Odum et al., 2006). It is possible that similar results would be obtained with human participants in choice arrangements more similar to the ones examined in the current experiment. Moreover, money can be used to obtain a wide variety of reinforcers, including food and drugs. It is possible that money is a more effective reinforcer than food or drugs because of its fungability, and therefore is discounted at a shallower rate. However, a fungible reinforcer does not exist for nonhuman subjects.

Drug abuse is often conceptualized in terms of an allomorphic situation in which individuals choose more immediate drug effects over more delayed non-drug alternatives. From this perspective, the results of the current study may be more ecologically valid for understanding drug abuse because the allomorphic situation is more similar to what drug abusers actually experience (i.e., a choice between more immediate drug effects over more delayed non-drug alternatives). We believe the most important finding in this experiment is that the nature of the choice situation (i.e., allomorphic vs. isomorphic) was an important determinant of the degree to which a delayed non-drug reinforcer was discounted. This observation raises the possibility that allomorphic choice situations are key to understanding the determinants of immediate drug choice. It will be important for future research to examine whether similar effects occur in allomorphic situations with drugs of abuse from different drug classes and with drug combinations that are commonly co-abused, as well as different non-drug reinforcers (e.g., highly palatable foods and other non-drug alternatives). Moreover, allomorphic choice provides an important approach to identifying and developing behavioral and pharmacological treatments that increase choice of delayed, non-drug alternatives. We believe it will be important for future research to determine whether treatments or other manipulations that have been studied under isomorphic situations produce similar outcomes in allomorphic ones. Finally, given the differences obtained between isomorphic and allomorphic situations, we believe it will be necessary to examine more thoroughly other contextual variables that modulate discounting rates.

References

- Anderson KG, Woolverton WL. Effects of dose and infusion delay on cocaine self-administration choice in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2003;167:424–430. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Perry JL, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME. Impulsivity predicts the escalation of cocaine self-administration in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2009;93:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: Similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Jones BA, Kurth-Nelson Z, et al. Single- and cross-commodity discounting among cocaine addicts: The commodity and its temporal location determine discounting rate. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert AL, Green L, Myerson J. Delay discounting of qualitatively different reinforcers in rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2010;93:171–184. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2010.93-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ, Mach JL, Newman JL, Perry JL. Delay discounting as a predictor of drug abuse. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 243–271. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:18–25. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Mitchell SH. Drug effects on delay discounting. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Estle SJ, Green L, Myerson J, Holt DD. Discounting of monetary and directly consumable rewards. Psychological Science. 2007;18:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KB, Green L, Myerson J, Woolverton WL. Delay discounting of saccharin and rhesus monkeys. Behavioural Processes. 2009;82:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KB, Heal DJ, McCreary A, Woolverton WL. Assessment of ropinirole as a reinforcer in rhesus monkeys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KB, Nonnemacher JE, Green L, Myerson J, Woolverton WL. Delay discounting in rhesus monkeys: Equivalent discounting of more and less preferred sucrose concentrations. Learning and Behavior. 2012;40:54–60. doi: 10.3758/s13420-011-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KB, Wang Z, Woolverton WL. Self-administration of (+)-methamphetamine and (+)-pseudoephedrine, alone and combined, by rhesus monkeys. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2010;95:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano LA, Bickel WK, Loewenstein G, Jacobs EA, Marsch L, Badger GJ. Mild opioid deprivation increases the degree that opioid-dependent outpatients discount delayed heroin and money. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace RC. The matching law and amount-dependent exponential discounting as accounts of self-control choice. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1999;71:27–44. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace RC, Sargisson RJ, White KG. Evidence for a magnitude effect in temporal discounting with pigeons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2012;38:102–108. doi: 10.1037/a0026345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:769–792. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, Holt DD, Slevin JR, Estle SJ. Discounting of delayed food rewards in pigeons and rats: Is there a magnitude effect? Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004;81:39–50. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.81-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, McFadden E. Rate of temporal discounting decreases with amount of reward. Memory & Cognition. 1997;25:715–723. doi: 10.3758/bf03211314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myserson J, Ostaszewski P. Amount of reward has opposite effects on the discounting of delayed and probabilistic outcomes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1999;25:418–427. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.2.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey-Lewis C, Perdrizet J, Franklin KBJ. Delay discounting of oral morphine and sweetened juice rewards in dependent and non-dependent rats. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:2633–2645. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimura K, Myerson J, Hilgard J, Braver TS, Green L. Are people really more patient than other animals? Evidence from human discounting of real liquid rewards. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:1071–1075. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.6.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MJ, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;77:129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN. Bidding on the future: Evidence against normative discounting of delayed rewards. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1997;126:54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Marakovic NN. Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: Rates decrease as amounts increase. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1996;3:100–104. doi: 10.3758/BF03210748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KA. Delayed reinforcement of operant behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2010;93:129–139. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2010.93-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsive and self-control choices in opioid-dependent patients and non-drug-using control participants: Drug and monetary rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:256–262. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DR, Gerak LR, France CP. Delay discounting of food and remifentanil in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2013a;229:323–330. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3121-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DR, Gerak LR, France CP. Effect of delay on self-administration of remifentanil under a drug versus drug choice procedure in rhesus monkeys. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2013b;347:557–563. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.208355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons ML, Mazur JE, Nevin JA, Rachlin H, editors. Quantitative analysis of behavior: The effect of delay and of intervening events on reinforcement value. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchel SH. Effects of short-term nicotine deprivation on decision-making: Delay, uncertainty and effort discounting. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:819–828. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331296002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK. Effects of chronic d-amphetamine treatment on cocaine- and food-maintained responding under a second-order schedule in rhesus monkeys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003a;70:39–52. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK. Effects of chronic d-amphetamine treatment on cocaine- and food-maintained responding under a progressive-ratio schedule in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2003b;167:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1409-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JL, Perry JL, Carroll ME. Effects of altering reinforcer magnitude and reinforcement schedule on phencyclidine (PCP) self-administration in monkeys using an adjusting delay task. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2008;90:778–786. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Baumann AAL, Rimington DD. Discounting of delayed hypothetical money and food: Effects of amount. Behavioural Processes. 2006;73:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira L, Green L, Myerson J. Pigeons’ delay discounting functions established using a concurrent-chains procedure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2014;102:151–161. doi: 10.1002/jeab.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Carroll ME. The role of impulsive behavior in drug abuse. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Larson EB, German JP, Madden GJ, Carroll ME. Impulsivity (delay discounting) as a predictor of acquisition of IV cocaine self-administration in female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;178:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Nelson SE, Anderson MM, Morgan AD, Carroll ME. Impulsivity (delay discounting) for food and cocaine in male and female rats selectively bred for high and low saccharin intake. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2007;86:822–837. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Nelson SE, Carroll ME. Impulsive choice as a predictor of acquisition of IV cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16:165–177. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Raineri A, Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991;55:233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JB, Mitchell SH, de Wit H, Seiden LS. Determination of discount functions in rats with an adjusting-amount procedure. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1997;67:353–366. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1997.67-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6:292–305. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio Y, Higgins ST, Heil SH, McKerchar TL, Badger GJ, Skelly JM, Dantona RL. Delay discounting is associated with treatment response among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;19:243–248. doi: 10.1037/a0023617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Anderson KG. Effects of delay to reinforcement on the choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0355-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Freeman KB, Myerson J, Green L. Suppression of cocaine self-administration in monkeys: Effects of delayed punishment. Psychopharmacology. 2012;220:509–517. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2501-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Myerson J, Green L. Delay discounting of cocaine by rhesus monkeys. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:238–244. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Mitchell SH, Bickel WK. Delay discounting and substance abuse-dependence. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Higgins ST, Bradstreet MP, Badger GJ, Thomas CS. Changes in the relative reinforcing effects of cigarette smoking as a function of initial abstinence. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:305–318. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Sugarbaker RJ, Thomas CS, Badger GJ. Delay discounting predicts postpartum relapse to cigarette smoking among pregnant women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:176–186. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]