Abstract

First-line therapy for pancreatic cancer is gemcitabine. Although tumors may initially respond to the gemcitabine treatment, soon tumor resistance develops leading to treatment failure. Previously, we demonstrated in human MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells that N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC), a glutathione (GSH) precursor, prevents NFκB activation via S-glutathionylation of p65-NFκB, thereby blunting expression of survival genes. In this study, we documented the molecular sites of S-glutathionylation of p65, and we investigated whether NAC can suppress NFκB signaling and augment a therapeutic response to gemcitabine in vivo. Mass spectrometric analysis of S-glutathionylated p65-NFκB protein in vitro showed post-translational modifications of cysteines 38, 105, 120, 160 and 216 following oxidative and nitrosative stress. Circular dichroism revealed that S-glutathionylation of p65-NFκB did not change secondary structure of the protein, but increased tryptophan fluorescence revealed altered tertiary structure. Gemcitabine and NAC individually were not effective in decreasing MIA PaCa-2 tumor growth in vivo. However, combination treatment with NAC and gemcitabine decreased tumor growth by approximately 50%. NAC treatment also markedly enhanced tumor apoptosis in gemcitabine-treated mice. Compared to untreated tumors, gemcitabine treatment alone increased p65-NFκB nuclear translocation (3.7-fold) and DNA binding (2.5-fold), and these effects were blunted by NAC. In addition, NAC plus gemcitabine treatment decreased anti-apoptotic XIAP protein expression compared to gemcitabine alone. None of the treatments, however, affected extent of tumor hypoxia, as assessed by EF5 staining. Together, these results indicate that adjunct therapy with NAC prevents NFκB activation and improves gemcitabine chemotherapeutic efficacy.

Keywords: Gemcitabine, Glutathione, N-acetyl-l-cysteine, Pancreatic cancer, S-glutathionylation

1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer has the worst prognosis of all major cancers with an unchanged 5-year survival rate of less than 5% [1–4]. The annual incidence of pancreatic cancer is nearly equivalent to its annual mortality, estimated to be 38,460 in the US for 2013 [1]. Pancreatic cancer patients receive little benefit from current therapies that result in 97% treatment failure. Gemcitabine, a nucleoside analogue of deoxycytidine, is the standard treatment for pancreatic cancer but as a single agent is poorly effective [5]. Although tumors may initially respond to the gemcitabine treatment, a subset of tumor cells soon emerges that escape the treatment and display multidrug resistant. Several innovative trials have been designed to increase the treatment efficacy by combining gemcitabine with other chemotherapeutic drugs. Unfortunately, many of these trials have been associated with high toxicities and/or lack of significant improvement of efficacy compared to gemcitabine alone [6,7].

One of the targets considered for combination therapy is the transcription factor NFκB. NFκB is a redox-regulated transcription factor that is linked with cell proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis, suppression of apoptosis, and chemo-resistance in multiple tumors [8–12]. NFκB proteins modulate transcription by binding distinct DNA target sites known as κB DNA sequences. Each NFκB family protein has a conserved domain of ∼300 amino acids (aa) known as the Rel-homology region (RHR) located at the N-terminus (aa 1–332). The RHR consists of a DNA-binding domain, a dimerization domain, and a nuclear localization signal [13]. The carboxyl termini (aa 299–550) of NFκB family proteins are divided into two classes, depending on the presence (p65, RelB and c-Rel) or absence (p50 and p52) of the transactivation domain (TAD). NFκB is constitutively activated in most cancers including pancreatic cancers, indicating that NFκB plays a major role in growth and chemo-resistance of pancreatic cancer [14].

NFκB inhibits apoptosis, promotes cell growth and enhances angiogenesis via increased expression of pro-angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [15]. NFκB-regulated gene products promote migration and invasion of cancer cells [16]. In fact, inhibition of constitutive NFκB activity is sufficient to suppress pancreatic tumorigenesis and metastasis [17]. NFκB also promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer [5]. Together, these findings suggest that agents which block NFκB activation can reduce chemo-resistance to gemcitabine. Therefore, their use in combination with gemcitabine would provide a novel therapeutic approach for pancreatic cancer.

N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) is a widely used thiol-containing antioxidant that is a precursor of de novo GSH synthesis. Of the three amino acids of GSH (i.e., glutamate, glycine, and cysteine), cysteine has the lowest intracellular concentration. Because de novo synthesis is the primary mechanism by which GSH is replenished, cysteine availability can limit the rate of GSH synthesis in oxidative stress-related diseases [18]. NAC treatment provides cysteine equivalents for GSH supplementation. Accordingly, NAC acts not only as a direct thiol antioxidant but also contributes to regulation of cell signaling under oxidative stress by replenishing GSH [19]. Animal studies show that dietary intake of NAC can decrease the severity of many diseases including cancer, pancreatitis, cardiovascular diseases, HIV infections, acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity and metal-induced toxicity [20,21]. NAC is used primarily as an antidote in acetaminophen overdose [22,23]. NAC is also used to avert exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), prevent kidney damage during imaging procedures, attenuate illness from the influenza virus and treat pulmonary fibrosis [18].

Our previous studies showed that NAC induces apoptotic cell death in hypoxic human pancreatic cancer cells by inhibiting NFκB transcriptional activity via S-glutathionylation of p65-NFκB [24,25]. Therefore, we hypothesized that NAC-induced NFκB inactivation would increase the efficacy of gemcitabine treatment in animal models of pancreatic cancer. In this study, we show that NAC markedly enhances the efficacy of gemcitabine to decrease tumor growth in pancreatic tumors. This increased efficacy is mediated by inactivation of NFκB and suppression of anti-apoptotic proteins, such as XIAP. Furthermore, mass spectrometric (MS) analysis of recombinant p65-NFκB in vitro identified several cysteines on p65-NFκB as potential sites for S-glutathionylation. Circular dichroism (CD) spectral analysis showed that the secondary structure of p65-NFκB was unaltered, but tryptophan fluorescence revealed that the tertiary structure of the p65-NFκB protein was modified by S-glutathionylation. These changes likely impact transcriptional activation by p65-NFκB without disrupting its nuclear translocation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Matrigel was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Monoclonal anti-NFκB-p65, anti-actin and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, MA). Propidium iodide and Alexa 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and DRAQ-5 from Alexis Biochemicals, (San Diego, CA). 2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3 penta-fluoropropyl) acetamide (EF5) and antibody detecting EF5 were generous gifts from Dr. Cameron J. Koch (University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine, USA). Recombinant human NFκB-p65 (12–317, untagged) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY). In situ cell death detection kit based on the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) method was from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). OCT embedding medium was from Leica Biosystems (Buffalo, IL). PABA/NO was prepared as previously described [26]. NAC, GSH, GSSG reductase (yeast) and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Cell culture

Human MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic carcinoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were grown in complete culture medium containing Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (50 units/mL of penicillin and 50 μg/mL of streptomycin) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cells were grown to a 60–70% confluence before treatments.

2.3. Animal tumor model

Male athymic nude mice (5–6 weeks, strain Nu/J, inbred homozygous) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in the pathogen-free athymic mice facility of the Hollings Cancer Center at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Animal rooms were maintained at constant temperature and humidity on a daily 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. Mice were fed with regular autoclaved chow diet with water ad libitum and allowed one week to acclimate to the animal facilities before the start of experiments. All animal procedures were carried out in compliance with the institutional animal care and use committee at MUSC.

MIA PaCa-2 cells (2.5 × 106) were injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of the athymic mice. Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix (4.5 mg/mL) was added to the cell suspensions (1:1). When tumor volumes reached 100–200 mm3, mice were randomized and divided into four groups: saline (vehicle treatment); NAC (100 mg/kg, i.p., thrice weekly); gemcitabine (100 mg/kg, i.p., once weekly by i.p. injection); and gemcitabine plus NAC. Tumor size was monitored weekly with a caliper, and tumor volume (V) was estimated using the formula: V = (Width2 × Length)/2. Mice were weighed once a week. Tumor volumes were recorded on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 of treatment. All mice were sacrificed on day 35. Three hours prior to sacrifice, mice were injected i.v. with EF5 (30 mg/kg) in PBS. After tumor excision, half of the tumor tissue was frozen on dry ice in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) embedding medium for cryosectioning. Sections were then used for immunohistochemistry and H&E staining. The other half of the tumor tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for Western blot and biochemical assays.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

Tumor sections were cut to thickness of 10 μm. Hypoxic regions were detected by EF5 adducts using the ELK3-51-CY3 antibody [27]. OCT-frozen tumor sections were fixed with 4% formalin for 1 h at 4 °C, permeabilized with 1% Tween 20 and blocked overnight to reduce nonspecific binding according to a previously published report [27]. ELK3-51-CY3 antibody was titrated, and a dilution of 1:500 was chosen for an optimal signal-to-noise ratio. Finally, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS with Hoechst (1 μM) to stain the nuclei. Images of Hoechst and CY3 fluorescence were collected with an Olympus IX81 inverted epifluorescence microscope using a 10× objective, DAPI and DsRed filter cubes, and MetaMorph acquisition software.

To assess p65-NFkB nuclei translocation, tissue sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. After washes with Tris-buffered saline supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), cells were incubated with blocking solution (1% BSA in TBST) for 1 h followed by primary monoclonal antibody against p65-NFκB (1:100) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were then washed three times with TBST and incubated with anti-mouse secondary Alexafluor 568 (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature, and followed by three washes with PBS. Hoechst dye was included in the final wash to stain the nuclei. Images of Alexafluor 568 and Hoechst fluorescence were collected using an Olympus FV10i LIV laser scanning confocal microscope (405-nm excitation/420–460-nm emission and 543-nm excitation/560-nm long pass emission) fitted with a 60 × N.A. 1.2 water immersion planapochromat objective. Nuclei showing co-localization of Hoechst and Alexafluor 568 fluorescence were counted for each treatment group.

2.5. Nuclear extracts

Nuclear extracts were prepared according to a modification of the method of Wang et. al. [14]. Briefly, tissues (∼ 0.5 g) were thawed from −80 °C in 5 ml of ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and washed times with ice-cold PBS plus protease inhibitors. The tissues were then minced into small pieces and homogenized in ice-cold PBS plus protease inhibitors in a Dounce/Polytron homogenizer for 20 sec. Homogenates were then centrifuged at 500 × g for 3 min at 4 °C. The pellets were lysed in 500 μl of low salt buffer (20 mM HEPES, 20% glycerol, 10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.6) on ice. To complete the lysis, 50 μl of 10% NP-40 was added, and the tubes were vigorously vortexed for 10 s. After 15 min incubation, the extracts were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected as cytoplasmic extracts. Nuclear pellets were resuspended in high salt buffer (20 mM HEPES, 20% glycerol, 500 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.6); and tubes were rotated for 15 min at 4 °C, centrifuged at 14,000 × g, and supernatants saved as nuclear extracts.

2.6. NFκB activation and DNA binding

Specific binding of activated NFκB was measured with a Trans-AM™ NFκB kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The oligonucleotide containing the NFκB consensus sequence (5′-GGGACTTTCC-3′) is immobilized onto a 96-well-plate. Only the active form of NFκB in the cell extract specifically binds to the oligonucleotide. Epitopes on p50, p52, p65, c-Re1 and Re1 B are accessible only when NFκB is bound to its target DNA. Nuclear extracts (−10 μg) were added to the wells followed by the primary antibody against p65 and the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Optical density at 450-nm was measured with an absorbance plate reader.

2.7. Western blot analysis

Tissues (∼ 0.5 g) were thawed in 5 mL of ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail and washed 3 times with ice-cold PBS plus protease inhibitor. The tissue samples were then minced into small pieces and suspended in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors followed by homogenization in a Dounce/Polytron homogenizer for 20 sec. Tissue homogenates were then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants (tissue lysates) were assayed for total protein content (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equivalent amounts of protein were diluted in sample buffer (200 mM Tris–HCl, 15% glycerol, 10% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, pH 6.8) and resolved on SDS-PAGE gels. The proteins were then transferred and immobilized on PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and probed with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. Membranes were developed using the enhanced chemilumines-cence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and band intensities were quantified using a Carestream 4000 PRO image station (Woodbridge, CT).

2.8. TUNEL assay

Tissue sections were stained using the in situ cell death detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. TUNEL positive nuclei (red) were counted in 10 different microscope fields in each sample. Images were collected with a BD Biosciences CARV II spinning disc confocal microscope using a 20 × objective.

2.9. CD and tryptophan spectra

Consequences of S-glutathionylation on secondary and tertiary structure were examined as described previously [26,28]. Recombinant p65-NFκB protein (40 μg) was incubated with GSH (10 mM) and diamide (3 mM) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 37 °C for 30 min. The protein was purified from the reaction mixture by size-exclusion chromatography using a BS-6 (Bio-Rad, CA) micro column equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Far-UV CD spectra of p65 and S-glutathionylated p65 (p65-SSG) proteins (50 μM in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) were recorded on an AVIV model 62DS spectrometer (Aviv Associates) using a quartz cuvette with 2-mm path length. Each sample was scanned 3 times at 190–260 nm in 1 nm steps using a bandwidth of 4 nm at 22 °C. Spectra were smoothed and baseline corrected by solvent subtraction. The recorded spectra were converted to molecular (mean residue) ellipticity. The p65 samples were recovered after CD analysis, diluted 10 times with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and used for analysis of tryptophan fluorescence on a QM-4 spectrofluorometer (PTI Inc., NJ) in a quartz cuvette at 22 °C under constant stirring. The tryptophan emission was recorded using 295-nm (2-nm bandwidth) excitation and 305-455-nm (4-nm band width). All spectra were smoothed and corrected by solvent subtraction.

2.10. Mass spectroscopic analysis

S-glutathionylation of cysteine residues of p65-NFκB was evaluated following oxidative and nitrosative stress. For oxidative stress, recombinant p65-NFκB protein (40 μg) was incubated with GSH (10 mM) and diamide (3 mM) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 37 °C for 30 min. For nitrosative stress, recombinant p65 was incubated with 1 mM GSH and 25 μM PABA/NO in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 30 min at 37 °C. After removal of excess GSH and PABA/NO by size exclusion chromatography, samples were run on non-reducing SDS-PAGE gels. Gel bands were excised and digested with trypsin overnight and analyzed via liquid chromatography (LC)-electrospray ionization (ESI)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) on a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ, Thermo Scientific) coupled to an LC Packings nano LC system.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Differences were assessed by two-sided paired Student's t-test with Instat Software (GraphPAD, San Diego, CA). A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Tumor growth was modeled over time using a linear mixed model including day from treatment initiation (measured as a continuous variable), treatment groups and their interaction as fixed effects, and a mouse-specific random effect to account for the correlation of tumor volumes measured in the same mouse over time. Tumor volume at treatment initiation was included as a model covariate to adjust for differences in tumor volumes at baseline. The effect of treatment on tumor volume at specific time points was evaluated by constructing model-based linear contrasts. All tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was declared based on a P value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Combination of gemcitabine and N-acetyl-l-cysteine inhibits tumor growth by inducing apoptotic death

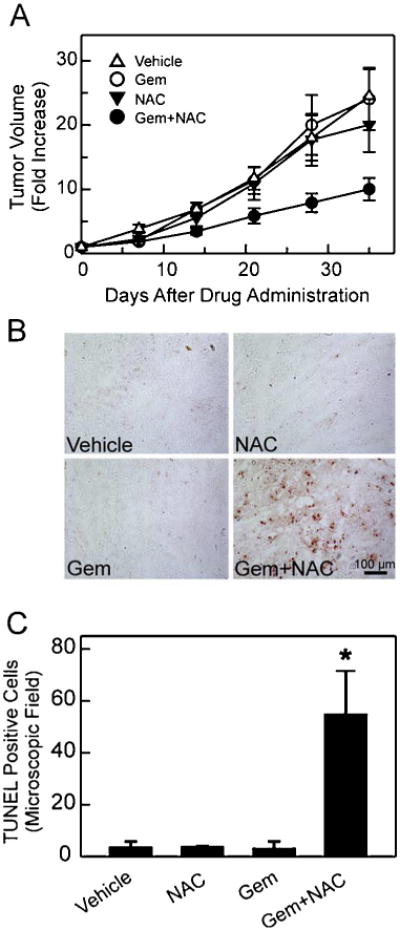

Male athymic mice bearing MIA PaCa-2 xenografts were monitored for tumor growth. Tumors continued to grow in vehicle, gemcitabine and NAC treatment groups. At day 35, tumor volumes increased by 20–24 fold in all three of these treatment groups (Fig. 1A). By contrast, the combination treatment of gemcitabine and NAC markedly decreased the tumor growth from day 21 post-treatment onwards compared to vehicle- and single agent-treated groups (P < 0.001 Gem + NAC versus Gem; P < 0.0001 Gem + NAC versus vehicle) (Fig. 1A). The results indicate that although gemcitabine and NAC individually failed to decrease tumor growth the combination of these two agents greatly increased treatment efficacy.

Fig. 1.

Combination of gemcitabine and N-acetyl-l-cysteine induces apoptosis and suppresses tumor growth. A. MIA PaCa-2 cells (2.5 × 106) were injected into mice s.c., and tumor growth was measured with a caliper. Tumor volume on the treatment start day was set to 1. Rates of tumor growth are expressed as fold increase in tumor volume. Group sizes were vehicle, 18; NAC, 11; gemcitabine (Gem), 14; and Gem + NAC, 14. B. Frozen tumor sections were fixed, and apoptotic cells were detected by TUNEL as described in Section 2. Representative images are shown. C. TUNEL positive cells were counted using a 20 × objective. Ten different microscopic fields per slide were counted and averaged. Data represent 4 independent experiments for each treatment group and are expressed as number of TUNEL positive cells/microscopic field. *P < 0.05 compared to vehicle-, NAC-, and Gem-treated groups.

To assess whether combined treatment of gemcitabine and NAC induced apoptosis, TUNEL was performed. Gemcitabine or NAC as single agents did not induce apoptosis compared to vehicle, but the two agents together markedly increased apoptosis, indicating that the combination treatment is highly effective in potentiating apoptosis in tumors (Fig. 1B–C).

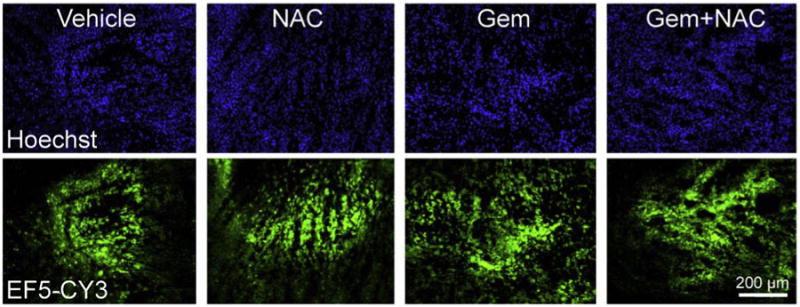

3.2. Combination of gemcitabine and N-acetyl-l-cysteine does not affect tumor hypoxia in pancreatic tumors

Limited vascularization is common in cancer and affects tumor oxygenation, leading to intratumor hypoxia, which is a key factor contributing to cancer progression. To assess whether any treatments altered the hypoxic tumor microenvironment, we identified hypoxic regions in tumors using the 2-nitroimidazole derivative EF5. EF5 binds to regions of hypoxia in a manner that is inversely proportional to oxygen concentration [27]. EF5 was injected at day 35 and then three hours later the mice were sacrificed. Images were acquired after immunohistochemical staining for EF5 (Fig. 2). Tumor tissue sections from mice treated with vehicle, NAC, gemcitabine, and gemcitabine plus NAC all showed patchy regions of EF5 binding (green), consistent with heterogeneous binding and the presence of hypoxic tumor regions (Fig. 2). No consistent differences between treatment groups were observed.

Fig. 2.

Gemcitabine and N-acetyl-l-cysteine treatments do not affect tumor hypoxia in pancreatic tumors. Frozen tumor sections were fixed and stained with anti-EF5-CY3 antibody to mark hypoxic regions and with Hoechst to stain nuclei, as described in Section 2. Fluorescence due to CY3-antibody binding to adducted EF5 is a marker of hypoxia. Images are representative of 4 independent experiments for each treatment group.

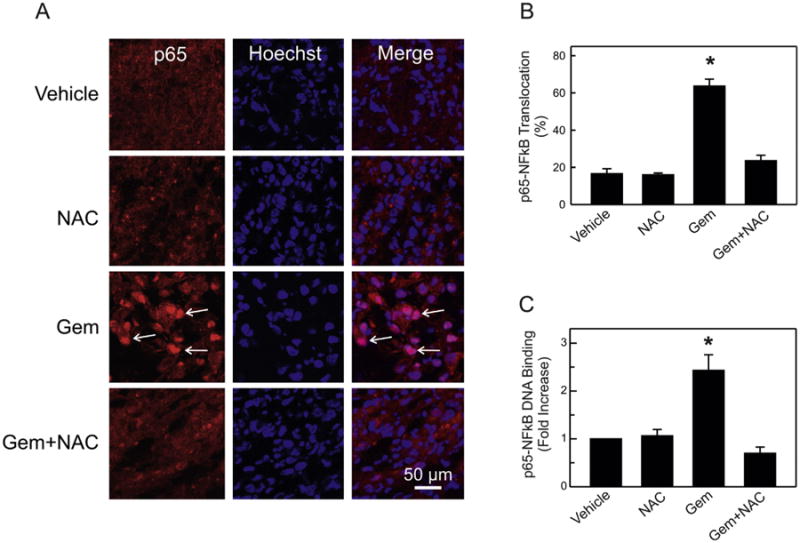

3.3. N-acetyl-l-cysteine blocks gemcitabine-induced p65-NFκB activation by preventing its DNA binding in tumors

To examine further the mechanism(s) by which NAC enhances gemcitabine efficacy to induce apoptosis in pancreatic tumors, we assessed p65-NFκB nuclear translocation and DNA binding in all treatment groups. Immunohistochemistry revealed that cells in the vehicle- and NAC-treated tumors showed little p65-NFκB translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 3A). Unexpectedly, gemcitabine treatment induced substantial p65-NFκB nuclear translocation, as shown as strong p65 immunolabeling of Hoechst-stained nuclei (Fig. 3A, Gem, arrows). Gemcitabine treatment induced 64% p65-NFκB nuclear translocation compared to 17 and 16% for vehicle- and NAC-treated tumors, respectively (Fig. 3B). By contrast, the combination of gemcitabine with NAC markedly blocked p65-NFκB nuclear translocation caused by gemcitabine alone (Fig. 3A bottom; Fig. 3B). As measured by the Trans-AM™ NFκB kit, gemcitabine increased p65-NFκB DNA binding by 2.5 fold compared to vehicle-treated tumors, and this increase also was completely blocked by combination with NAC (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that gemcitabine-induced NFκB activation likely contributes to chemo-resistance associated with the gemcitabine treatment. NAC by blocking NFκB activation enhances the efficacy of gemcitabine.

Fig. 3.

Combination of N-acetyl-l-cysteine with gemcitabine blocks gemcitabine-induced p65-NFκB nuclear translocation and activation in pancreatic tumors. A. Tissue sections were processed, probed with p65-NFκB antibody and counterstained with Hoechst dye for nuclei. Images of Alexafluor 568 and Hoechst were collected by confocal microscopy as described in Section 2. Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown. B. Nuclei showing co-localization of Hoechst and Alexafluor 568 fluorescence were counted in 8 different fields per microscope slide. Data from analysis of 500 cells per treatment group were obtained from 5 mice per treatment group. Results are expressed as % of cells with p65-NFκB nuclear translocation. *P < 0.001 compared to other groups. C. p65-DNA binding was measured in nuclear extracts with an ELISA, as described in Section 2. Data are from 5 mice per treatment group performed in triplicate. Results are expressed as fold increase compared to vehicle-treated samples. *P < 0.005 compared to other groups.

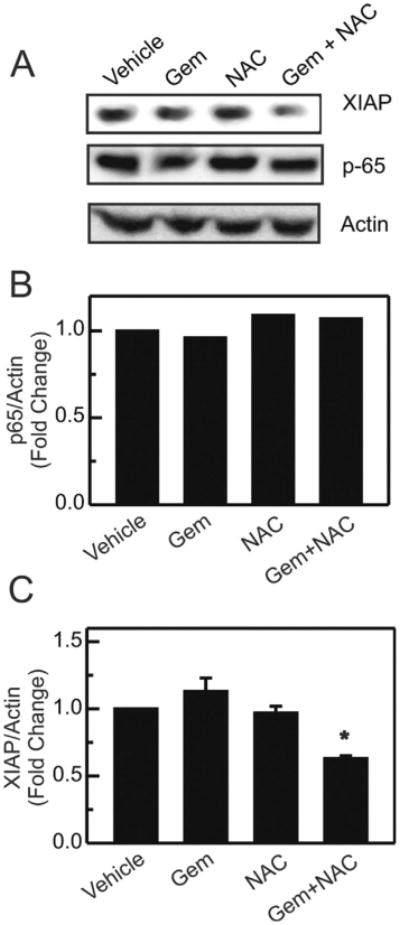

3.4. N-acetyl-l-cysteine decreases gemcitabine-induced XIAP protein expression

NFκB is a survival factor that regulates various anti-apoptotic genes, including X chromosome-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP/hILP), an inhibitor of caspases 3, 7 and 9 [15]. Our previous studies showed that NAC inhibited hypoxia-induced XIAP protein expression in MIA PaCa2 cells [25]. Here, we assessed the effect of gemcitabine on XIAP protein expression in pancreatic tumors. Compared to vehicle-treated tumors, gemcitabine treatment caused a trend toward increased XIAP protein expression that was not statistically significant (Fig. 4A and C). NAC treatment alone had no effect on XIAP protein. By contrast, the combination of gemcitabine and NAC decreased XIAP protein expression significantly (Fig. 4A and C). To confirm that decreased XIAP protein expression in the gemcitabine plus NAC-treated tumors was not due to diminution of total NFκB protein content (decreased expression or increased degradation), p65-NFκB protein levels were also determined. Indeed, all treatment groups displayed indistinguishable levels of p65-NFκB protein (Fig. 4B), indicating that the observed decrease in XIAP protein expression (Fig. 4C) was due to inhibition of NFκB activation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Combination of N-acetyl-l-cysteine plus gemcitabine inhibits XIAP protein expression in tumors. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting for p65-NFκB, XIAP and actin, as described in materials and methods. Representative blots and corresponding band intensities normalized to actin for p65 are shown in (A) and (B). (C) Band intensities were quantified for XIAP. Data are averaged from 4 mice per treatment group, and results were expressed as fold change from vehicle-treated mice. *P < 0.005 compared to Gem- and NAC-treated groups.

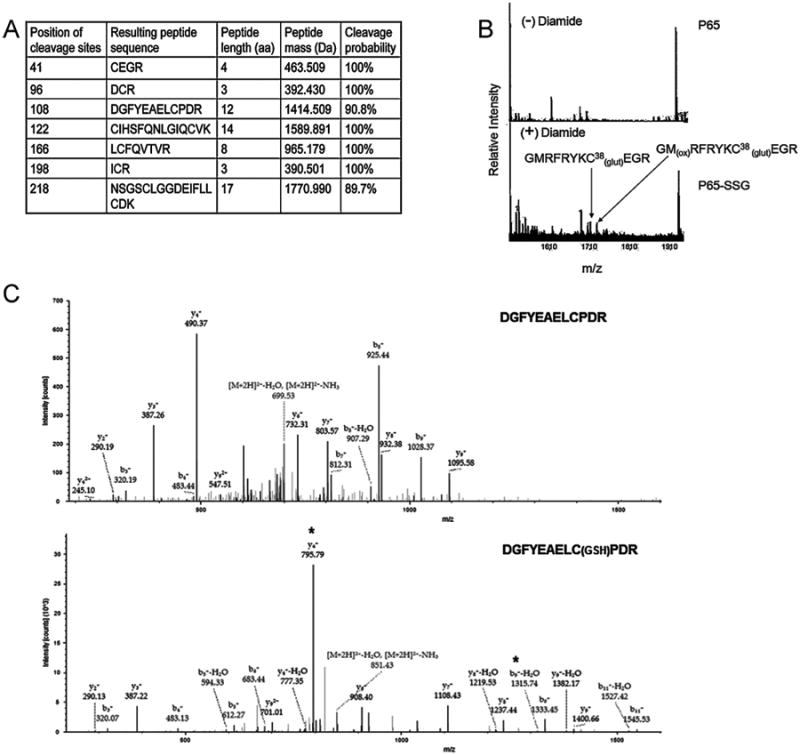

3.5. Cysteines on p65-NFκB are potential sites for S-glutathionylation

Our previous studies indicated that p65-NFκB was inhibited by S-glutathionylation (p65-SSG) in MIA PaCa-2 cells [24,25]. Tryptic digestion of purified p65-NFκB yielded seven cysteine-containing peptides with a total of nine cysteine residues, which represent possible sites of S-glutathionylation (Fig. 5A). Accordingly, we performed a comprehensive mass spectrometric analysis of the p65-NFκB recombinant protein after treatment with GSH (10 mM) plus diamide (3 mM) (Fig. 5B). S-glutathionylated peptides were identified by 1) a mass shift of [+305.6 Da] compared to the unmodified peptide and 2) unique fragmentation patterns observed in MS/MS data consistent with cysteine modification. Fig. 5B represents the spectra where S-glutathionylation was detected at Cys38. Fig. 5C represents the LC-ESI-MS/MS spectra whereby an S-glutathionylated modification [+305] was detected at Cys105 of the p65 following PABA/NO treatment. Additional sites for the p65 S-glutathionylation were detected at Cys120, 160, 216 (data not shown). Collectively, MS data indicated that out of the nine cysteines, five were S-glutathionylated following oxidative and/or nitrosative stress, suggesting that these could be potential S-glutathionylation sites of p65- NFκB in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Several cysteine residues on p65-NFkB are potential sites for S-glutathionylation. Tryptic digestion of recombinant p65 protein yields seven peptides containing 9 cysteines (A). Recombinant p65 protein was treated with GSH (10 mM) plus diamide (3 mM) (B) and GSH (1 mM) plus PABA/NO (25 μM) (C). The p65 proteins were digested under non-reducing conditions and analyzed via MS/MS (B) and LC-ESI-MS/MS (C), as described in Section 2. *indicates modified peaks at the y4 and b9 ions. Unmodified (top) and PABA/NO-treated (bottom) (C).

3.6. S-glutathionylation of p65 alters protein structure

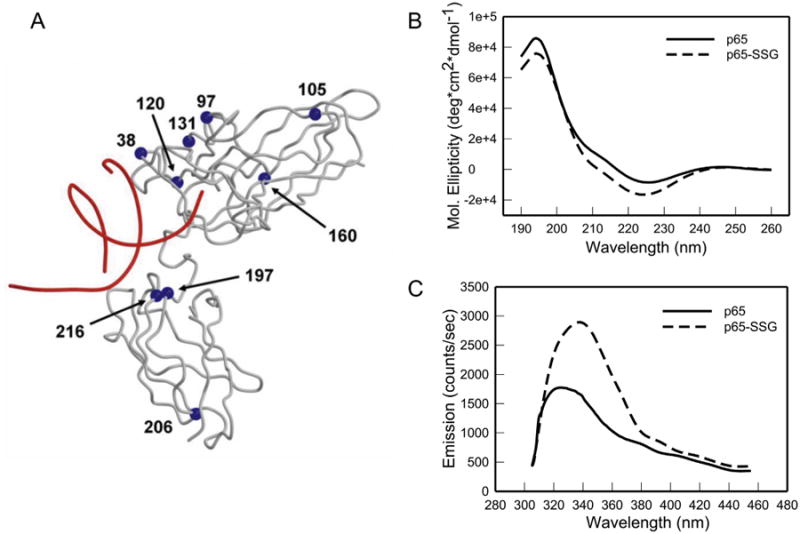

Fig. 6A indicates the locations ofcysteines near the DNA binding site of p65 [29–31]. The Cα positions of these cysteines (blue spheres) were projected onto the crystal structure of p65 (grey backbone), which was solved as a p50–p65 heterodimer in complex with DNA (red backbone) (Fig. 6A). Many of the critical cysteines (Cys38, 120, 160, 216) that were glutathionylated in recombinant p65-NFκB are present in or adjacent to the DNA-binding domain of the protein (Fig. 5). Since S-glutathionylation of p65 might lead to structural changes that alter its DNA-binding capacity, we analyzed the effect of S-glutathionylation on the secondary structure of p65 by CD spectrometry comparing recombinant p65 with S-glutathionylated p65 (p65-SSG). Such CD spectra (190–260 nm) generate information about the percentage of α-helix, β-sheet, and irregular structure. However, CD spectra of the p65 and p65-SSG were virtually identical indicating that the secondary structure of the protein was intact after S-glutathionylation (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

S-glutathionylation of p65 alters protein structure. A. Crystal structure of p65-NFκB indicates the locations of cysteines proximal to the DNA in p65 (arrows). The Cα positions of the cysteines (blue spheres) are projected onto the crystal structure of p65 (grey backbone), which was solved for the p50–p65 heterodimer in complex with DNA (red backbone). For clarity, p50 is not shown. B. CD spectra of native p65 and S-glutathionylated p65 (p65-SSG) recombinant protein were generated as described in Section 2. The spectra are average of three independent experiments.C. p65 protein tryptophan fluorescence was recorded before and after treatment with GSH (10 mM) and diamide (3 mM), as described in Section 2. Spectra are the average of three independent experiments.

Intrinsic protein tryptophan fluorescence of p65 and p65-SSG was also measured using an excitation wavelength of 295-nm to minimize the contributions of tyrosine and phenylalanine to the fluorescence. Glutathionylation of p65 caused a near doubling of tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 6C). Since S-glutathionylation of a cysteine adjacent to a tryptophan produces fluorescence quenching rather than increased fluorescence, the observed increase of tryptophan fluorescence likely indicates an alteration of p65-NFκB tertiary structure by S-glutathionylation. Such alteration in the protein structure could result in the observed inhibition of the p65-DNA binding [26].

4. Discussion

This study provides mechanistic insights regarding how inhibition of NFκB activation potentiates regression of pancreatic tumors by gemcitabine. The results indicate paradoxically that gemcitabine treatment by itself activates p65-NFκB pro-survival signaling. This activation is markedly suppressed by co-administration of NAC, resulting in inhibition of NFκB-mediated anti-apoptotic target genes, such as XIAP.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas belong to the most aggressive solid malignancies. The poor prognosis for treatment of these tumors is associated with a high degree of resistance to current systemic therapy regimens. Although gemcitabine is a first-line treatment for pancreatic cancer, fewer than 20% of patients are benefited by the treatment [32]. Constitutive NFκB activity is present in 70% of human pancreatic cancers and in several pancreatic carcinoma cell lines that serve as effective models, including MIA PaCa-2 [33]. Since NFκB activation plays a major role in resistance against chemotherapeutic drugs, we reasoned that the MIA PaCa2-induced xenograft model would be useful for evaluating agents capable of overcoming gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic tumors.

Gemcitabine as a single agent had no inhibitory effect on tumor growth as compared to vehicle-treated tumors (Fig. 1A). However, combination treatment with gemcitabine plus NAC greatly decreased tumor growth compared to single agent treatments or vehicle. Decreased tumor growth appeared due to increased apoptotic cell death, at least in part (Fig. 1B–C). In cells, gemcitabine interferes with DNA synthesis through incorporation into DNA, inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [34,35]. Nonetheless, gemcitabine treatment alone failed to induce apoptosis in the MIA PaCa-2 tumor xenografts (Fig. 1B–C), suggesting that gemcitabine activates certain signaling pathways that are inhibited by the co-administration of NAC.

Our previous results showed that NAC supplementation in several hypoxic pancreatic cancer cell lines including MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1, ASPC-1 and Capan-2 and promoted apoptosis by suppressing the NFκB survival pathway [24] [unpublished results]. Pancreatic cancers are frequently characterized by regions of hypoxia, a feature that correlates with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis compared with well-oxygenated tumors [36,37]. Marked enhancement of cell killing by NAC in the presence of gemcitabine might reflect a diminution of the hypoxic condition thereby dampening hypoxia-associated survival responses. Qualitative analysis of tumor hypoxia with EF5 staining revealed numerous EF5-positive hypoxic regions within the pancreatic tumors. However, there was no indication of diminished hypoxia with combination treatment compared to the single treatments or vehicle (Fig. 2), indicating that decreased tumor growth effect of the NAC plus gemcitabine treatment was not related to hypoxia.

Previously, we showed that hypoxia activated p65-NFκB in MIA PaCa-2 cells in vitro and this activation was blunted by NAC resulting in apoptotic cell death [24]. Similarly, gemcitabine treatment also generated strong p65-NFκB nuclear translocation and activation that were diminished by NAC (Fig. 3). Our results do not distinguish whether NFκB activation originated exclusively from hypoxic tissue regions. However, this interpretation is unlikely because no difference in NFκB activation and tissue hypoxia was evident between vehicle- and NAC-treated tumors. Thus, NFκB activation likely originates from gemcitabine-treated hypoxic and normoxic tissues.

Gemcitabine induces intracellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in pancreatic cancer cells, although the contribution of ROS to gemcitabine-induced cancer cell killing is still controversial [38,39]. The study by Donadelli et al. showed that gemcitabine-induced ROS plays a role in gemcitabine-mediated cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer cells, since NAC blunted ROS production and protected cells against gemcitabine toxicity [38]. In contrast, a recent study by Arora et al. concluded that gemcitabine-induced ROS production contributed to NFκB-mediated gemcitabine resistance, which was reversed by NAC in MIA PaCa-2 cells in vitro [39]. Although this study was performed in cultured cells, its data support our conclusion that gemcitabine-induced NFκB activation contributes to gemcitabine associated chemo-resistance in vivo (Figs. 1 and 3).

NFκB activates several genes associated with survival pathways, including expression of XIAP [40]. Previously, we showed NFκB-dependent XIAP protein expression in hypoxic MIA PaCa-2 cells [25]. In MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic tumors, we observed that the combination of NAC and gemcitabine decreased XIAP protein levels to well below the XIAP levels detected in untreated tumors (Fig. 4). Since p65-NFκB protein levels were unchanged among all treatment groups, the decrease in XIAP protein levels appeared to be transcriptionally regulated. These results together with documentation of enhanced apoptosis with gemcitabine plus NAC treatment (Fig. 1) indicate that inhibition of NFκB-dependent expression of XIAP protein is at least in part responsible for NAC-induced suppression of gemcitabine-treated tumor growth.

NAC is a precursor of GSH and increases intracellular GSH content. Under pro-oxidant conditions, GSH itself can bind covalently to reactive cysteine thiols of proteins to form mixed disulfides, resulting in the post-translational modification of S-glutathionylation [41,42]. Previously, we showed that suppression by NAC of NFκB activation and apoptosis in hypoxic MIA PaCa-2 cells was due to reversible S-glutathionylation of p65-NFκB, resulting in inhibition of its binding to DNA [24]. NAC-mediated inhibition of p65-NFκB and subsequent apoptosis was GSH-dependent and not due to inhibition of ROS formation since other antioxidants, such as the vitamin E analog trolox and epigallocatechin-3-gallate, did not enhance apoptosis [25]. Here, MS analysis of purified recombinant S-glutathionylated p65-NFκB showed that 5 of nine possible p65-NFκB cysteine residues – Cys38, 105, 120, 160, 216 – became S-glutathionylated under conditions simulating either oxidative or nitrosative stress (Fig. 5). Lin and coworkers also showed that multiple cysteine residues within p65 are targets for S-glutathionylation and that Cys38, 160, 216 are critical to transcriptional activity in endothelial cells [43,44]. Our mass spectrometry and transcriptional activation data support their findings. However, due to sensitivity issues, we could not assess S-glutathionylation of NFκB in vivo in pancreatic tumors after gemcitabine plus NAC treatment, which will be the subject of future study.

CD spectra and measurements of tryptophan fluorescence showed that S-glutathionylation of p65-NFκB did not change secondary structure of the protein but did alter tertiary structure (Fig. 6). Alteration in the tertiary structure could result in inhibition of the p65-DNA binding. Interpretation of the results from in vitro experiments with S-glutathionylated p65-NFκB in light of the X-ray structure of the NFκB-DNA complex (Fig. 6A) would suggest if Cys38 or Cys120 is glutathionylated, decreased DNA binding and transactivation would be the consequence, since Cys38 is in direct contact with DNA and Cys120 is very near to DNA. In contrast, Cys97, 105, 131, 206 are surface residues with no DNA contacts, so their modification is less likely to alter p65-NFκB function. Cys160, 197, 216 are within the hydrophobic core, so their S-glutathionylation would be expected to perturb folding of the p65 subunit (Figs. 5 and 6), disrupting NFκB function allosterically. Thus, site-selective S-glutathionylation of p65 in vivo would likely lead to NFκB inactivation. Moreover, gemcitabine-induced ROS production may create an oxidative tumor microenvironment that favors S-glutathionylation of p65-NFκB in the presence of NAC [38,39].

In summary, our results shed light on the mechanisms responsible for gemcitabine chemoresistance in vivo. Chemotherapeutic strategies to prevent NFκB activation associated with gemcitabine treatment show promise to improve gemcitabine efficacy and clinical outcome for pancreatic cancer. Combination treatment with NAC is an attractive approach because NAC is already FDA-approved as a safe treatment for acetaminophen overdose. NFκB is a powerful transcription factor that regulates several beneficial signaling pathways that are crucial for the human body. Therefore, formulations that would target NAC specifically into tumors and thereby avoid systemic NFκB inhibition might further improve the therapeutic index of the gemcitabine and NAC combination treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants R01 CA119079 (ALN), NCRR P20RR024485 and R56 ES017453 (DMT and JDU), VA Merit Review Grant BX000290 (JJM), P30 CA138313 (Hollings Cancer Center Cell and Molecular Imaging and Biostatistics Shared Resources and pilot research funding), SCTR Institute UL1TR000062, NCRR C06 RR015455. We thank Dr. Christopher Davis for the drawing of the simplified representation of the p65 crystal structure. We also thank the Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics Core and the Mass Spectrometric Facility at the Medical University of South Carolina for the mass spectrometric analyses.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almhanna K, Philip PA. Defining new paradigms for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2011;12:111–25. doi: 10.1007/s11864-011-0150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Neill CB, Atoria CL, O'Reilly EM, LaFemina J, Henman MC, Elkin EB. Costs and trends in pancreatic cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118:5132–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrystoja CC, Diamandis EP, Brand R, Ruckert F, Haun R, Molina R. Pancreatic cancer. Clin Chem. 2013;59:41–6. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.196642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warsame R, Grothey A. Treatment options for advanced pancreatic cancer: a review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:1327–36. doi: 10.1586/era.12.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. Folfirinox versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tholey R, Sawicki JA, Brody JR. Molecular-based and alternative therapies for pancreatic cancer: looking “out of the box”. Cancer J. 2012;18:665–73. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3182793ff6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M. NF-kappaB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:379–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madonna G, Ullman CD, Gentilcore G, Palmieri G, Ascierto PA. NF-kappaB as potential target in the treatment of melanoma. J Transl Med. 2012;10:53. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujioka S, Son K, Onda S, Schmidt C, Scrabas GM, Okamoto T, et al. Desensitization of NFkappaB for overcoming chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer cells to TNF-alpha or paclitaxel. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4813–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorriento D, Illario M, Finelli R, Iaccarino G. To NFkappaB or not to NFkappaB: the dilemma on how to inhibit a cancer cell fate regulator. Transl Med. 2012;4:73–85. UniSa. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang TP, Vancurova I. NFkappaB function and regulation in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2013;3:433–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huxford T, Malek S, Ghosh G. Structure and mechanism in NF-kappa B/I kappa B signaling. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1999;64:533–40. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, Larry L, Cleary KR, Chiao PJ. The nuclear factor-kappa B RelA transcription factor is constitutively activated in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang CY, Guttridge DC, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB induces expression of the Bcl-2 homologue A1/Bfl-1 to preferentially suppress chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5923–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rayet B, Gelinas C. Aberrant rel/NFκB genes and activity in human cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:6938–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujioka S, Sclabas GM, Schmidt C, Frederick WA, Dong QG, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Function of nuclear factor kappaB in pancreatic cancer metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:346–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millea PJ. N-acetylcysteine: multiple clinical applications. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:265–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zafarullah M, Li WQ, Sylvester J, Ahmad M. Molecular mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine actions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:6–20. doi: 10.1007/s000180300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demols A, Van Laethem JL, Quertinmont E, Legros F, Louis H, Le MO, et al. N-acetylcysteine decreases severity of acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 2000;20:161–9. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimble RF. Nutritional antioxidants and the modulation of inflammation: theory and practice. New Horiz. 1994;2:175–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Betten DP, Cantrell FL, Thomas SC, Williams SR, Clark RF. A prospective evaluation of shortened course oral N-acetylcysteine for the treatment of acute acetaminophen poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:272–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai CL, Chang WT, Weng TI, Fang CC, Walson PD. A patient-tailored N-acetylcysteine protocol for acute acetaminophen intoxication. Clin Ther. 2005;27:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qanungo S, Starke DW, Pai HV, Mieyal JJ, Nieminen AL. Glutathione supplementation potentiates hypoxic apoptosis by S-glutathionylation of p65-NFkappaB. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18427–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qanungo S, Wang M, Nieminen AL. N-acetyl-L-cysteine enhances apoptosis through inhibition of NFkappa B in hypoxic murine embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50455–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Townsend DM, Manevich Y, He L, Hutchens S, Pazoles CJ, Tew KD. Novel role for glutathione S-transferase pi. Regulator of protein S-glutathionylation following oxidative and nitrosative stress. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:436–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805586200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch CJ. Measurement of absolute oxygen levels in cells and tissues using oxygen sensors and 2-nitroimidazole EF5. Methods Enzymol. 2002;352:3–31. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)52003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grek CL, Zhang J, Manevich Y, Townsend DM, Tew KD. Causes and consequences of cysteine S-glutathionylation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:26497–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.461368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkowitz B, Huang DB, Chen-Park FE, Sigler PB, Ghosh G. The x-ray crystal structure of the NF-kappa B p50.p65 heterodimer bound to the interferon beta-kappa B site. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24694–700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosh G, van Duyne G, Ghosh S, Sigler PB. Structure of NF-kappa B p50 homodimer bound to a kappa B site. Nature. 1995;373:303–10. doi: 10.1038/373303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang DB, Phelps CB, Fusco AJ, Ghosh G. Crystal structure of a free kappaB DNA: insights into DNA recognition by transcription factor NF-kappaB. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:147–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arlt A, Gehrz A, Muerkoster S, Vorndamm J, Kruse ML, Folsch UR, et al. Role of NF-kappaB and Akt/PI3K in the resistance of pancreatic carcinoma cell lines against gemcitabine-induced cell death. Oncogene. 2003;22:3243–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voutsadakis IA. Molecular predictors of gemcitabine response in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3:153–64. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i11.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong A, Soo RA, Yong WP, Innocenti F. Clinical pharmacology and pharmacogenetics of gemcitabine. Drug Metab Rev. 2009;41:77–88. doi: 10.1080/03602530902741828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bristow RG, Hill RP. Hypoxia and metabolism. Hypoxia, DNA repair and genetic instability. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:180–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koong AC, Mehta VK, Le QT, Fisher GA, Terris DJ, Brown JM, et al. Pancreatic tumors show high levels of hypoxia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:919–22. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00803-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donadelli M, Costanzo C, Beghelli S, Scupoli MT, Dandrea M, Bonora A, et al. Synergistic inhibition of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell growth by trichostatin A and gemcitabine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1095–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arora S, Bhardwaj A, Singh S, Srivastava SK, McClellan S, Nirodi CS, et al. An undesired effect of chemotherapy: gemcitabine promotes pancreatic cancer cell invasiveness through reactive oxygen species-dependent, nuclear factor kappaB- and hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha-mediated up-regulation of CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:21197–207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.484576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collett GP, Campbell FC. Overexpression of p65/RelA potentiates curcumin-induced apoptosis in HCT116 human colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1285–91. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shelton MD, Chock PB, Mieyal JJ. Glutaredoxin: role in reversible protein s-glutathionylation and regulation of redox signal transduction and protein translocation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:348–66. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shackelford RE, Heinloth AN, Heard SC, Paules RS. Cellular and molecular targets of protein S-glutathiolation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:940–50. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao BC, Hsieh CW, Lin YC, Wung BS. The glutaredoxin/glutathione system modulates NF-kappaB activity by glutathionylation of p65 in cinnamaldehyde-treated endothelial cells. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116:151–63. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin YC, Huang GD, Hsieh CW, Wung BS. The glutathionylation of p65 modulates NF-kappaB activity in 15-deoxy-Delta(1)(2),(1)(4)-prostaglandin J(2)-treated endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1844–53. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]