Abstract

IGF-1 is one of the key molecules in cancer biology; however, little is known about the role of the preferential expression of the premature IGF-1 isoforms in prostate cancer. We have examined the role of the cleaved COO– terminal peptide (PEc) of the third IGF-1 isoform, IGF-1Ec, in prostate cancer. Our evidence suggests that endogenously produced PEc induces cellular proliferation in the human prostate cancer cells (PC-3) in vitro and in vivo, by activating the ERK1/2 pathway in an autocrine/paracrine manner. PEc overexpressing cells and tumors presented evidence of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, whereas the orthotopic injection of PEc-overexpressing, normal prostate epithelium cells (HPrEC) in SCID mice was associated with increased metastatic rate. In humans, the IGF-1Ec expression was detected in prostate cancer biopsies, where its expression correlates with tumor stage. Our data describes the action of PEc in prostate cancer biology and defines its potential role in tumor growth, progression and metastasis.

INTRODUCTION

The role of IGF-1 as a potent growth and survival factor in human cancer is long established. The IGF-1 gene gives rise to multiple heterogeneous transcripts, all resulting in the mature form of the IGF-1 (1–4). Recent studies have suggested the preferential expression of the IGF-1Ec isoform in prostate cancer (5), whereas the exogenous administration of a synthetic 24-amino acid peptide of the COO– terminal of the Ec isoform (parts of exons 5 and 6 of the IGF-1 gene), has been associated with a statistically significant increase in proliferation in PC-3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cells (5). The effects of this synthetic PEc have been proposed to be generated by extra-cellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) but not Akt, promoting prostate cancer cell growth in vitro (5). Unlike IGF-1, the effects of PEc were not mediated via the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R), the insulin receptor (IR) or any of the hybrid receptors (IGF-1R/IR) (5,6). Mechanistically, the synthetic PEc has been suggested to be involved in the migration and invasion of murine mesenchymal cells (4,7,8). Despite this evidence, some studies present contradictory results regarding the action of synthetic PEc in muscle cells (9,10). Therefore the role of Ec in cancer biology remains to be elucidated.

The aim of this study is to shed light on the role of PEc in prostate cancer. Our results suggest that PEc is a key molecule in tumor growth and survival and it also is involved in the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenomenon of prostate cancer cells leading to metastases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Prostate tissues were obtained from 78 prostate cancer patients with a clinically localized disease, who underwent radical prostatectomy with curative intent. The tissues were obtained from the Archives of Metropolitan Hospital, Athens, Greece following the institutional and the local Ethics Committee rules for the use of archive material. Human bone marrow was collected from a 32-year-old patient with an open femur fracture and blood lymphocytes were isolated from whole blood from a 40-year-old healthy male. A written informed consent (IC) was obtained by all subjects. These IC had been approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and all the experimental procedures conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell Cultures

Wild type PC-3 cells (wtPC-3), an androgen resistant, p53-negative and Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras) mutated human prostate cancer cell line (11) were obtained from American Type Cell Culture (ATCC, Bethesda, MD, USA). Passage six wtPC-3 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Cambrex, Walkerville, MD, USA), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biochrom, Berlin, Ger-many) and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Cambrex). Immortalized HPrEC cells (stably transfected with the SV40 large T antigen and the human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene) were obtained from William C Hahn (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Harvard Medical School) and maintained in prostate epithelial basal medium (PrEBM) enriched with the single quotes according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Constructs

The PEc DNA sequence of the human IGF-1Ec (TATCAGCCC CCATCTACCA ACAAGAACAC GAAGTCTCAG AGAAGGAAAG GAAGTACATT TGAAGAACGC AAGTGC) was synthetically produced and cloned into the pJ express 603 vector (DNA 2.0 Company, Menlo Park, CA, USA) This sequence contained a start GCGACACCATG and a stop codon TAAAAA. In addition, the TGC triplet was added that prior to forming a cysteine at the COO terminal of our construct for isolation and stabilization purposes. The bioactivity of both synthetic peptides (with and without the cysteine) was examined in respect to their effect on cellular proliferation in wtPC-3 cells and in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (11). Both synthetic peptides presented similar effects when applied on wtPC-3 cells (no statistical significance differences were observed). The construct was examined by enzyme digest and by bidirectional sequencing. Stable transfectants, wtPC-3 and immortalized HPrEC cells were examined with quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) and with immunofluorescence (12).

Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM)

Briefly, total protein from cell lysates went through a Amicon 3kDa spin column with 50 mmol/L ammonium bicarbonate to eliminate RIPA (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl; 150 mmol/L NaCl) buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) before digestion. Reduction and alkylation was carried out with dithiothreitol (DTT) and iodoacetamide, followed by overnight tryptic digestion. The samples were applied on a stage tip to clean the sample before mass spectrometry analysis. Samples have been solubilized into 50 μL of 0.1% formic acid containing 5 fmol/μL of a standard peptide (ASSILAT).

For each sample, 2 μL were injected into a 5500 Qtrap (AbSciex, Framingham, MA, USA). Peptides were eluted over an 18 min acetonitrile gradient and three peptides were monitored: YQPPSTNK and GSTFEER (from peptide E) and ASSILAT (normalization). For each peptide, at least five transitions were monitored to improve the signal specificity.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The secreted PEc in the media of PC-3PEc cells and of PC-3IGF-1Ec KD cells was estimated by an in-house direct ELISA method. For the standard curve, we coated wells with different concentrations of the synthetic PEc (0 to 1 μg/mL). 0.5% serum media obtained after 48 h incubation from either mPC-3, wtPC-3 PC-3PEc and PC-3IGF-1Ec KD cells were placed into the wells of a 96-well plate and allowed to coat it. After washing the excess media, a custom-made rabbit anti-human anti-IGF-1Ec antibody (5) at 1:5,000 dilution was introduced. The anti-IGF-1Ec or anti-PEc antibody was raised against the PEc; and therefore apart from the PEc, the antibody also recognizes the IGF-1Ec isoform that contains the Ec peptide (PEc). Detection was carried out with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody at 1:1,000 dilution (Thermo Scientific [Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA]). As a substrate, we used TMB. The reaction stopped with 2 mol/L sulphuric acid. The absorption of the plate was measured within 20 min at 450 nm and 540 nm as reference using a microplate reader (VersaMax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Transient siRNA Knockdown (KD) of the IGF-1R and ZEB1

IGF-1R silencing in PC-3 cells was carried out as described previously (5). We used the commercially available Stealth siRNA technology (Invitrogen [Thermo Fisher Scientific]). The sequence used was the UCUUCAAGGGCAAUUUGCUCAUUAA siRNA duplex and ZEB1 silencing in PC-3 PEc overexpressing cells was carried out by using six certified Stealth technology siRNA (Invitrogen [Thermo Fisher Scientific]) sequences. From these, the most potent duplex (GCUGAGAAGCCUGAGUCCUCUGUU) was used. Both siRNAs were used at a concentration of 40 pmol, again by using reverse transfection using RNAiMAX lipofectamine (Invitrogen [Thermo Fisher Scientific]), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As a negative control, we used a universal negative control Stealth siRNA (Invitrogen [Thermo Fisher Scientific]) separate in each case. The KD efficiency was examined 48 h after the transfection.

Stable siRNA KD of the IGF-1Ec

PEc was silenced in wtPC-3 cells by stable siRNA transfection using the psiRNA-h7SKneo G1 kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary oligonucleotides compatible with BbsI restriction enzyme prior to their insertion into the psiRNA-h7SKneo vector were designed using the siRNA Wizard software (www.sirnawizard.com). The oligonucleotides used were these: forward: ACCTCGAGAA GGAAAGGAAG TACATTTCAA GAGAATGTAC TTCCTTTCCT TCTCTT; and reverse: CAAAAAGAGA AGGAAAGGA AGTACATTCT CTTGAAATGT ACTTCCTTTC CTTCTCG. The siRNA insertion was confirmed by enzyme digest with SpeI and by bidirectional sequencing using the primers provided by the kit (forward OL559 and reverse OL408).

Cell Proliferation

MTT assay

Wt and modified PC-3 and HPrEC cells were plated at a cell density of 750 cells/well in 96-well plates and grown with DMEM containing 10% FBS. After 24 and 48 h, the cells were cultivated with 10% MTT as described previously (12,13). MTT assays measure mainly the metabolic activity of cells in culture, indirectly associated with cell viability status.

Trypan blue exclusion assays

PC-3 and HPrEC cells were plated at a cell density of 3.5 × 104 cell/well in 6-well plates and grown with DMEM containing 10% FBS. After 24 h and 48 h of seeding cells, the cell number was counted as described previously (13–17). Trypan blue assays determine the actual cell number of living cells.

Western Blot Analysis

PC-3 cells were seeded and grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS. The FBS was reduced to 0.5% 24 h prior to various treatments. Cells were then exposed to various stimuli for 15, 30 and 60 min. The cell extracts were obtained by lysis in RIPA buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 150 mmol/L NaCl, Sigma-Aldrich) containing 0.55 Nonidet P-40, protease 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin; (Sigma-Aldrich) and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mmol/L sodium ortovanadate, 1 mmol/L NaF) (Sigma-Aldrich). After 30 min incubation on ice, the lysates were cleared by centrifugation (19,722g ) (15 min, and 4°C). Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amount of cell lysates (20 μg) were heated at 95°C for 5 min, electrophoresed on 12% SDS–PAGE under denaturing conditions and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The blots were blocked with TBS-T (20 mmol/L Tris–HCl [pH 7.6], 137 mmol/L NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat dried milk at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were probed overnight with primary antibodies. The primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-IGF-1Ec (anti-PEc) (1:10,000) (custom-made), rabbit anti-phospho and total ERK1/2 and rabbit anti-phospho and total Akt (1:1,000), (all from Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA, USA); rabbit anti–glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH), anti-β-actin (1:1,000), anti-ZEB1 (1:1,000), anti-Twist (1:200), (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); anti-Snail (1:1,000) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK); anti-cdc-6 (1:1,000) (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA); and mouse anti-human IGF-1R antibody (1:500) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The blots were washed and followed by incubation with a secondary goat antibody raised against rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:2,000 dilution); (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The bands were visualized by exposure the blots to x-ray film after incubation with freshly made ECL substrate for 3 min (SuperSignal, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen [Thermo Fisher Scientific]). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in the Bio-Rad iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system, using SYGR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Each reaction was performed in triplicate and values were normalized to GAPDH (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR primers.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| PEc | 5′-TATCAGCCCCCATCTACCA-3′ | 5′-CTTGCGTTCTTCAAATGTACTTCCT-3′ |

| IGF-1R | 5′-GGGAATGGAGTGCTGTATG-3′ | 5′-TCCTCCGCCTCCTGCTGCAGGTTCTT-3′ |

| E-cadherin | 5′-TGGAGGAATTCTTGCTTTGC-3′ | 5′-CGTACATGTCAGCCAGCTTC-3′ |

| Vimentin | 5′-GACAATGCGTCTCTGGCACGTCTT-3′ | 5′-TCCTCCGCCTCCTGCAGGTTCTT-3′ |

| ZEB1 | 5′-TTCAGCATCACCAGGCAGTC-3′ | 5′-GAGTGGAGGAGGCTGAGTAG-3′ |

Subcutaneous Injections in SCID Mice

Male SCID mice (6 wks old) were obtained from Democretos Laboratory and Pasteur Institute, Greece. Mouse handling and experimental procedures were approved by the Hellenic Ministry of Rural Development and Food, General Directorate of Veterinary. Animal handling and experimental procedures were obtained in the Experimental Surgery Laboratory of the Athens Medical School. Implantations were carried out as described previously (18). Briefly, a suspension of 5 × 106 cells in 200 μL in 1× PBS was injected subcutaneously in each mouse.

Orthotopic Injections in SCID Mice

Orthotopic implantations were carried out as described previously (19). Briefly, a suspension of 5 × 106 cells in 50 μL of a 1:1 mixture of PBS and Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) were injected into the prostate of SCID mice. Anesthesia was obtained by a solution of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylasine (12 mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich) administrated intraperitoneally (IP).

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence

Cultured cells on chamber slides were stained by an indirect immunofluorescence method. Cells were rinsed in PBS and fixed with ice cold 80% methanol for 10 min at room temperature. They were permeabilized with PBS plus 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min. They were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: rabbit anti-E-cadherin (1:100, Abcam) or rabbit anti-IGF-1Ec (1:1,000) or mouse anti-vimentin (1:100, Abcam) in PBS. After three washes with PBS, 5 min at room temperature, cells were incubated for 30 min with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to the fluorescent Alexa 488 dye (1:2,000, Abcam) or with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to the fluorescent Alexa 555 dye (1:2,000, Abcam) in PBS. After three washes, samples were stained with DAPI (1 μg/mL) for viewing with microscope (Olympus BX40; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

FACS

Adherent cells were washed with PBS and fixed overnight at 4°C in 70% ethanol. The cells were stained with CyStain DNA 1 step kit (Partec, Münster, Germany). DNA content was analyzed on a Partec flow cytometer (Partec), at 24 and 48 h using the ModFit LT software Flow max 3.0 (Verity Software House, NY, USA) (20).

Immunohistochemistry

Formaldehyde-fixed prostate samples were paraffin wax embedded and processed for paraffin sections. Microtome sections of 3 μm were allowed to adhere to glass slides, dried at 37°C overnight, dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in serial dilutions of ethanol. The sections were then incubated with the same primary antibody used for the Western blot analyses, that is, the polyclonal anti-IGF-1Ec antibody at a dilution of 1:1,000 in PBS overnight at 4°C. Secondary biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Dako Real EnVision; Dako Glostrup, Denmark) was then added and tissue sections were visualized under light microscopy (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), while negative control staining procedures were also included in all immunohistochemical analyses as described elsewhere (5). Samples were photographed using a digital camera (Nikon DS-2 MW; Nikon). Image analysis was performed in six random fields from each slide using the Image Pro Plus 5.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). IGF-1Ec (brown staining) average intensity levels, measured using arbitrary units on a linear scale from 0 (representing black) to 255 (representing white), and the average percentage of the extent of brown staining are combined in the following equation: IGF-1Ec expression = 255 – average intensity levels of brown staining × average percentage of extent of brown staining.

The mean intensity and extent of levels of brown staining for the six representative optical fields was estimated in each case and compared.

Statistical Analysis

The results obtained by the trypan blue and MTT analyses were assessed by the two-tailed equal variance Student t test (SPSS v. 11 statistical package; SPSS [IBM, Armonk, NY, USA]). Statistical significance was set at p values less than 0.05 (p < 0.05).

The results obtained from the prostate cancer patients’ tumors were analyzed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for analysis of variance in all continuous variables. The choice of methods for statistical testing of continuous variables was based on whether the data permitted parametric or nonparametric analysis. Comparisons of IGF-1Ec expression between groups was accordingly performed using Student t test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All supplementary materials are available online at www.molmed.org.

RESULTS

IGF-1Ec Expression in Prostate Cancer Biopsies

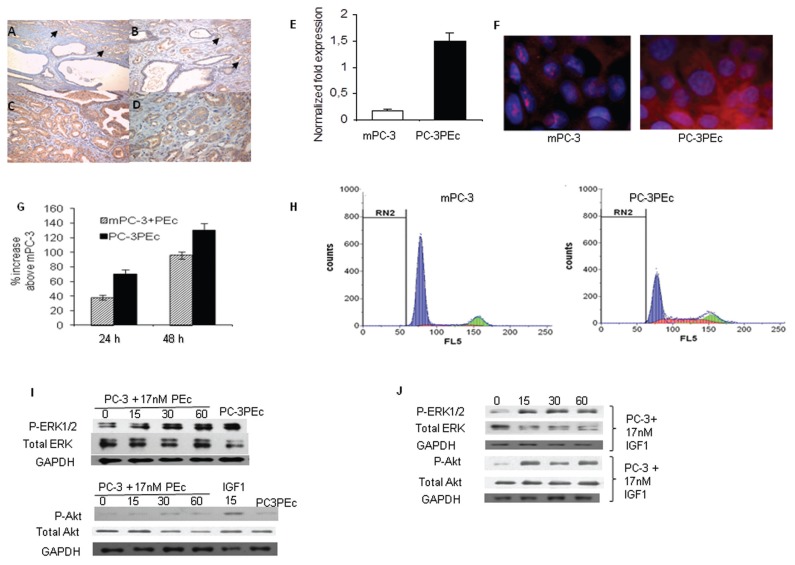

The levels of expression of IGF-1Ec were examined in randomly selected prostate cancer sections retrieved from the archives of Metropolitan Hospital. Seventy-eight prostate cancer patients were examined and the mean immunohistochemical expression of IGF-1Ec was found significantly lower in prostate cancer patients of stage ≤ IIb (AJCC) as compared with the tissues of patients of stage III and IV (p < 0.004). Mean IGF-1Ec expression was significantly lower in Stage IIa–IIb prostate tumors compared with Stage III (mean expression of IGF-1Ec was 101.3 versus 144.7, p = 0.005), (Figures 1A–D). These results concur with those previously described (5) and they suggest that IGF-1Ec expression is associated with prostate cancer stage.

Figure 1.

PEc is associated with the induction of proliferation in PC-3 cells. Immunohistochemical analysis of IGF-1Ec expression in human prostate biopsies: (A) benign columnar prostate epithelium and prostate cancer (arrows), 100×; (B) benign columnar prostate epithelium and prostate cancer (arrows), 200×; (C) prostate adenocarcinoma and high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia [PIN] 200×; (D) prostate adenocarcinoma and PIN, 400×. Actions of PEc in prostate cancer. (E) Detection of IGF-1Ec expression levels by qRT-PCR in mPC-3 cells (white column) and in PC-3 cells overexpressing the PEc (PC-3PEc) cells (black column). An at least six-fold increase of IGF-1Ec mRNA expression was detected in the PC-3PEc cells compared with the mock PC-3 (mPC-3) cells using GAPDH as a reference gene. (Student t test, p < 0.05, n = 6. Error bars refer to SD). (F) Immunofluorescence analysis of the PEc expression in mPC-3 and the PC-3PEc cells, using a polyclonal rabbit anti-human IGF-1Ec antibody. (G) Cell proliferation analysis using MTT assay. Exogenous PEc administration (17 nmol/L) induced the growth rate of wtPC-3 cells at 24 and 48 h. Increased cellular proliferation also was observed in PC-3PEc cell lines compared with mPC-3 cells, as measured at 24 and 48 h. (Student t test, p < 0.0001, n = 5. Error bars refer to SD). (H) Cell cycle analysis of mPC-3 and PC-3PEc cells using flow cytometry. PC-3PEc cells presented significantly lower distribution in the G1/G0 phase and higher distribution in the S phase as compared with mPC-3 cells (Student t test, p < 0.001, n = 3). RN2: range in gating; FL5: fluorescent light detector 5. (I) Western analysis of ERK1 and ERK2 (ERK1/2) and Akt phosphorylation in mPC-3 and PC-3PEc cells. Exogenous administration of synthetic PEc (17 nmol/L) induced ERK1/2 but not Akt phosphorylation in mPC-3 cells (0, 15, 30 and 60 min). PC-3PEc possessed constantly constitutive ERK1/2 activation without Akt being affected. (J) Exogenous IGF-1 (17 nmol/L) induced Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in mPC-3 cells at 15, 30 and 60 min (Western blot).

Ec Peptide Overexpression Leads to Increased Proliferation in PC-3 Cells

We therefore decided to examine the role of PEc overexpression in prostate cancer. On these grounds, we selected the wild type PC-3 (wtPC-3) prostate cancer cell line that expresses only a minor amount of IGF-1Ec compared with LNCaP prostate cancer cells and to human prostate epithelial cells (HPrEc) under tissue culture conditions (5). We generated PEc overexpressing PC-3 cells (PC-3PEc) and we compared them with the wild type mock PC-3 cells (mPC-3) (Figures 1E, F; Supplementary Figure S1). The mPC-3 cells were compared with wild type PC-3 cells in regards to cellular proliferation and to ERK1/2 phosphorylation and they did not present statistically significant differences (Supplementary Figures S2A, B, C). Our initial aim was to determine and compare the effects of the overproduction of endogenous PEc 24 (aa) with its exogenous administration in prostate cancer cells. Exogenous administration of synthetic PEc in mPC-3 cells increased their growth rate at 24 h (38% ± 3%) and at 48 h (96% ± 5%) (in both cases p < 0.0001). In addition, we documented a 70% (±6%) increase in the growth rate of PC-3PEc cells as compared with the mPC-3 cells 24 h after plating and an 130% (±7%) increase 48 h after plating using trypan blue and MTT assays (p < 0.0001) (Figure 1G). Cell cycle analysis suggested a significant increase of PC-3PEc cells in the S phase compared with the mPC-3 (27.02% versus 5.84%, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1H). Similarly to the exogenous PEc administration in mPC-3 cells, the cellular proliferation in PC-3PEc cells was associated with the activation of ERK1/2 but not Akt, in contrast to IGF-1, which was associated with ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation (Figures 1I, J). Similar results were observed in six different low-passage PC-3PEc clones. These data indicate that PC-3PEc cell presented similar characteristics to the mPC-3 cells stimulated by the exogenous administration of PEc.

PEc Generates PC-3 Proliferation via an Autocrine/Paracrine Mode of Action

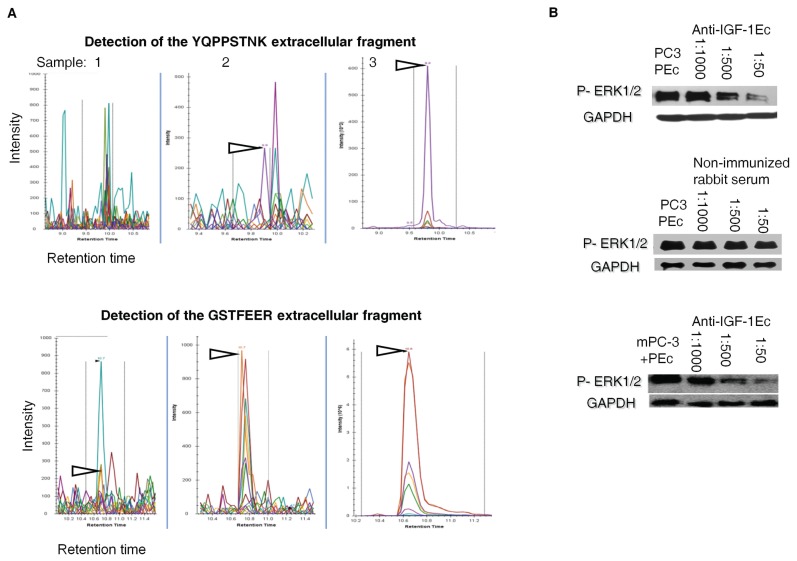

To determine whether the PEc in the PC-3PEc cells becomes extracellular, the PEc levels were examined in the media of PC-3PEc cells and of the mPC-3 cells by multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) analysis. It was found that PC-3PEc cells secrete a significant amount of PEc in contrast to mPC-3 cells (Figure 2A). Quantitation of the secreted PEc was also obtained by an in-house ELISA assay where it was found that PC-3PEc cells secrete significantly higher amounts of PEc compared with mPC-3 cells (6.20 ± 0.4 ng/mL versus 0 ng/mL, p < 0.001, n = 2, triplicate). Furthermore, incubation of PC-3PEc cells with different concentrations of anti-PEc antibody presented a significant gradual decrease of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 2B). These data, in conjunction with the fact that the exogenous administration of PEc is associated with an increase of Phospho ERK1/2 within 5 min, reaching a peak in 30 min, suggest that the ERK1/2 associated mode of action of PEc in mPC-3 cells is generated in an autocrine and/or paracrine fashion that involves the PEc secretion and the activation of proliferation via membrane/cytosolic signals.

Figure 2.

The PEc effects are generated in an autocrine/paracrine manner. (A) Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) protein analysis for the detection of the PEc-specific trypric products, (YQPPSTNK and GSTFEER) in the media of the mPC-3 and PC-3PEc. Sample 1: Tryptic products obtained from the media of mPC-3 cells. Sample 2: tryptic products of media obtained from PC-3PEc cells. Sample 3: tryptic products of synthetic PEc peptide (control). Significant amounts of both PEc tryptic products were detected into the PC-3PEc media. (B) Western analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in PC-3PEc cells and in mPC-3 cells after the administration of exogenous synthetic PEc, incubated with increasing concentrations of rabbit anti-human PEc (anti-PEc) antibody (1:1,000; 1:500 and 1:50), for 1 h. Anti-IGF-1Ec antibody significantly decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both cell types in a fashion that was directly proportional to the antibody concentration added in the culture media. In addition, nonimmunized rabbit serum did not affect the ERK1/2 phosphorylation in either system. In both cases, GAPDH was used as a control.

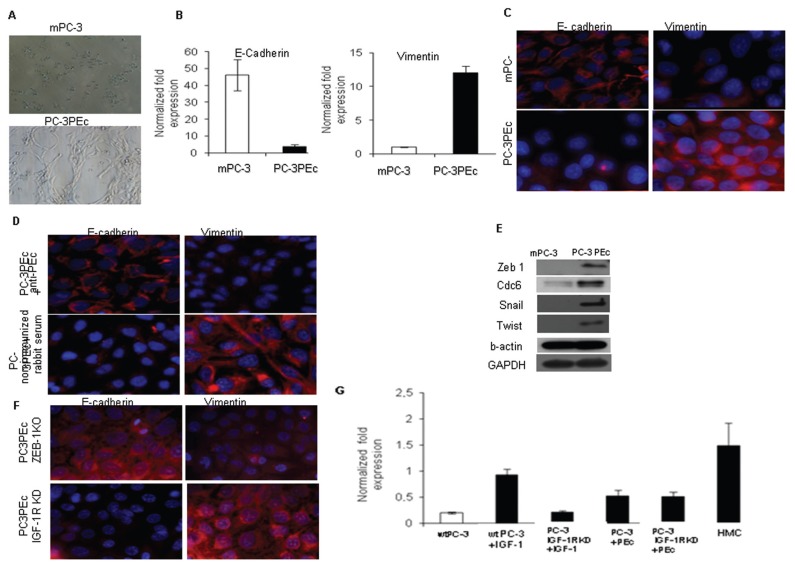

Association of Ec Peptide with the Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition Phenomenon (EMT)

PC-3PEc cells grown in vitro presented a fibroblast-like morphology under light microscope as compared with the epithelial-like mPC-3 cells (Figure 3A). Recent evidence suggests that the IGF-1 pathway induces the EMT phenomenon via the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) by upregulating the zinc finger enhancer binding protein 1 (ZEB1) in prostate carcinoma cells, which is stimulated by ERK1/2 phosphorylation (21,22,23). ZEB1 represses E-cadherin and it is involved in further chromatin condensation and gene silencing (24–27). E-cadherin loss is linked to increased tumor migration and invasion both in vitro and in vivo (28). Therefore, we examined the involvement of PEc in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a dynamic cellular process thought to underlie metastasis by promoting invasion, intravasation and extravasation (29–31). We documented a gradual E-cadherin decrease and a vimentin increase starting from 48 h, synchronously, reaching a peak of the effect within 72 h (Figures 3B, C). This suggests that the effect observed was not caused by the outgrowth of a specialized subset of cells. Treatment of the PC-3PEc cells with the anti-PEc antibody (administration in the media) led to the reversal of the mesenchymal phenotype (increase of E-cadherin expression and decrease of vimentin expression) at 24 h (Figure 3D). This finding fortifies the notion of the autocrine/paracrine mode of action of PEc.

Figure 3.

PEc overexpression induces EMT in PC-3 cells. (A) Analysis of the morphology of mPC-3 and PC-3PEc cells by light microscopy. PC-3PEc cells have a more spindle-like appearance compared with mPC-3 cells cultured under identical conditions. (B) PC-3PEc cells presented a significant decrease of E-cadherin and a significant increase of vimentin expression compared with mPC-3 cells as assessed by qRT-PCR (Student t test, P < 0.001 for both cases, n = 3). (C) Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of E-cadherin and vimentin expression in mPC-3 cells and in PC-3PEc cells. E-cadherin expression was suppressed and vimentin was increased in PC-3PEc cells. (D) The treatment of PC-3PEc cells with the anti-human IGF-1Ec antibody (anti-PEc, 1/50) reversed their E-cadherin and vimentin expression profile toward the mPC-3 phenotype (IF analysis). Nonimmunized rabbit serum did not affect E-cadherin and vimentin expression in PC-3PEc cells. (E) Western blot analysis of the Snail, Twist, ZEB1 and cdc6 proteins in mPC-3 and in PC-3PEc cells. These proteins’ expression was induced in PC-3PEc cells. GAPDH and β-actin were used as controls. (F) ZEB1 silencing was associated with an increase in the E-cadherin expression and a decrease in vimentin expression in PC-3PEc cells at 24 h after induction of the silencing, as shown by immunofluorescence. The silencing of the IGF-1R did not affect the E-cadherin and vimentin expression in PC-3PEc cell lines, suggesting that the IGF-1R is not involved in the PEc effects on E-cadherin and vimentin. (G) Analysis of the ZEB1 expression by qRT-PCR in wtPC-3 cells and PC-3 cells after silencing the IGF-1R (PC-3 IGF-1R KD), after the exogenous administration of IGF-1 and PEc (17 nmol/L in both cases). Exogenous IGF-1 induced the ZEB1 expression in wtPC-3 cells 24 h after its administration, but it did not affect the ZEB1 expression in PC-3 IGF-1R KD cells. Exogenous PEc had similar effects on ZEB1 expression that maintained in the PC-3 IGF-1R KD cells. Positive control: human mesenchymal cells (HMC).

Since PEc mode of action is associated with ERK1/2 activation, we also examined whether the PEc-induced EMT is mediated by ZEB1 expression, similar to that in IGF-1. Indeed PC-3PEc cells presented a more than five-fold increase in the ZEB1 expression level compared with mPC-3 cells (Figure S3). ZEB1 expression is regulated through a functional cooperation between Snail1 and Twist (32). On the other hand, it has also been suggested that, in cancer, EMT also can be promoted by the direct effect of cdc6 (cell division cycle 6), a protein involved in the replication licensing machinery, at the E-cadherin locus, as a molecular switch (33). Western Blot analysis presented evidence that PC-3PEc cells express the Snail, Twist, ZEB1 and cdc6 proteins in contrast to mPC-3 cells (Figure 3E). ZEB1 involvement in the PEc-associated EMT of PC-3 cells was verified by silencing the ZEB1 gene (Supplementary Figure S3A). The effects of this silencing on E-cadherin and vimentin were observed after 75 h (Figure 3F). To determine a possible involvement of IGF-1R in the PEc-induced EMT process, the ZEB1 expression levels were examined in mPC-3 and PC-3PEc cell lines after silencing their IGF-1R (IGF-1R KD) (Figure S4). It was determined in the PC-3 IGF-1R KD cells that although the IGF-1 exogenous administration did not affect the ZEB1 expression, the exogenous administration of PEc did increase the ZEB1 expression (Figure 3G). This data suggests that PEc induces the EMT in PC-3 cells via a different receptor molecule other than IGF-1R. In addition, the IGF-1R silencing in PC-3PEc cells did not affect their mesenchymal phenotype (morphology and the patterns of E-cadherin and vimentin) (Figure 3F).

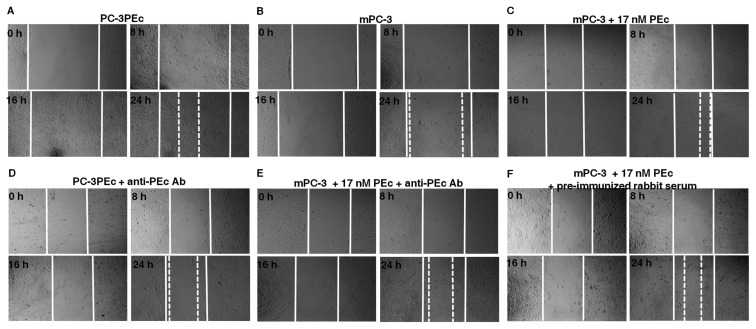

The effect of PEc on the migration ability of mPC-3 prostate cancer cells was also examined by scratch (migration) assays, where PC-3PEc cells and mPC-3 cells under the influence of the exogenous synthetic PEc were examined (Figure 4; Supplementary Figure S3B). It was observed that PC-3PEc cells (Figure 4A) presented an elevated migration rate compared with mPC-3 cells (Figure 4B) similar to that of mPC-3 cells under the influence of the exogenous synthetic PEc (Figure 4C). It was also observed that in both cases (PC-3PEc cells and mPC-3 cells after the administration of PEc) the anti-IGF-1Ec antibody led to a decrease of their migration rate (Figures 4D, E). As a negative control, we used nonimmunized rabbit serum (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Association of PEc with increased PC-3 cell mobility. (A–F) Wound healing assay, PEc effect on PC-3 mobility. Evaluation of the mPC-3 and PC-3PEc cells migration capacity at various time points (0, 8, 16 and 24 h). (A) PC-3PEc cells, (B) mPC-3 cells, (C) PC-3 cells after the exogenous administration of 17 ng/mL synthetic PEc, (D) PC-3PEc cells after the administration of the anti-PEc antibody in the media (1/50), (E) mPC-3 cells after the administration of synthetic PEc and of the anti-PEc antibody (1/50), (F) mPC-3 cells after the administration of synthetic PEc and of nonimmunized rabbit serum (1/50). PC-3PEc cells presented elevated migration capacity compared with mPC-3 cells. The administration of exogenous PEc stimulated the migration capacity in wtPC-3 cells. Treatment of PC-3PEc cells with the anti-PEc antibody decreased their migration capacity. Similarly the administration of the anti-PEc antibody to mPC-3 cells suppressed the stimulation of their migration capacity caused by the exogenous synthetic PEc. The migration pattern of PC-3PEc cells (single cells) was suggestive of mesenchymal nature in contrast to the migration pattern of wtPC-3 cells (sheet-like) indicating their epithelial nature.

Inoculation of PC-3PEc Cells into SCID Mice

PC-3PEc cells also were tested for their in vivo ability to produce subcutaneous tumors in SCID mice. WtPC-3 cells can generate tumors 4 wks after subcutaneous injection in SCID mice (34). mPC-3 cell-associated tumors were palpable after 25 d in 12 out of 15 mice. Subcutaneous inoculation of PC-3PEc cells led to the formation of palpable tumors within 20 d after injection in all the mice tested (15/15). At 35 d after the injections, the PC-3PEc tumors were macroscopically larger than the mPC-3 tumors (15/15). These tumors presented a significant size and mass difference when compared with the tumors caused by the mPC-3 cells (p < 0.001) (Figure 4A). This tumor size difference increased further in 45 d. At 40 d, satellite tumors were observed in close vicinity to the main lesion in all PC-3PEc-injected mice (15/15) (Figure 5A).

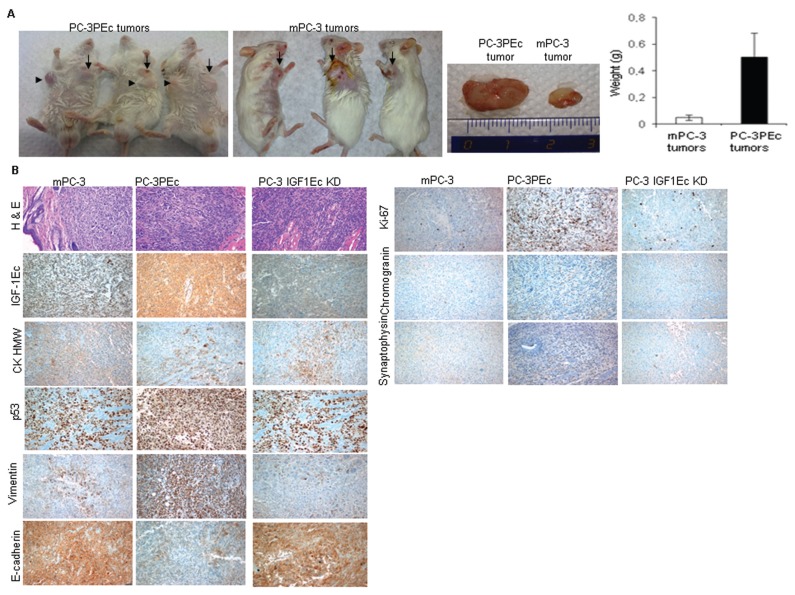

Figure 5.

In vivo effects of the PC-3PEc cells. (A) SCID mice injected with PC-3PEc cells produced larger tumors, in size and in weight, than those obtained from mPC-3 cells at the same time points. (Student t test, p < 0.001, n = 15. Error bars refer to SD) Arrows: point of the primary tumors. Arrowheads: points of tumors developed distal from the injection sites (35 d post-injection). (B) Immunohistochemi-cal analysis of mPC-3 induced and PC-3PEc induced tumors. PC-3PEc tumors documented with elevated expression of PEc compared with the wtPC-3 tumors. PC-3PEc tumors also contained an increased Ki-67 expression, which is a proliferation marker, and vimentin expression, while they had a decrease in E-cadherin expression as compared with mPC-3 tumors. In addition, PC-3PEc tumors presented decreased CKHMW levels and elevated chromogranin and synaptophysin levels compared with mPC-3 tumors, suggesting a possible neuroendocrine differentiation. Furthermore, we detected a relatively increased p53 expression in PC-3PEc tumors compared with the mPC-3 tumors. (C) Analysis of tumorigenesis in SCID mice injected with PC-3 cells after the silencing of the IGF-1Ec expression (PC-3 IGF-1Ec KD). These tumors presented slower tumor growth, compared with mPC-3 tumors and low tumorigenicity rate (20%, 2 out of 10). PC-3 IGF-1Ec KD tumors presented a similar expression pattern of prostate cancer markers examined in mPC-3 tumors, as observed by IHC.

Immunohistochemical examination of the resulting tumors documented that PEc overexpression was associated with an increase of the cellular proliferation marker ki-67, an increase of the vimentin, a decrease of E-cadherin expression and a slight increase in the expression of synaptophysin and chromogranin, suggesting possibly a neuroendocrine phenotype. Tumors that arose from mPC-3 cells seem to express the high molecular weight cytokeratin (CKHMW), a marker that is used to distinguish prostate cancer; however, the PC-3PEc tumors presented reduced levels of expression of CKHMW. Since the basal cell layer contains basal and neuroendocrine cells and CKHMW is expressed in basal cells, this data is compatible with the evidence obtained, suggesting an induction of neuroendocrine differentiation of PC-3PEc cells. PC-3PEc tumors also presented elevated p53 levels compared with mPC-3 tumors (Figure 5B). Knowing that p53 in wtPC-3 cells is not functional, this result can be explained as a response of the elevated tumorigenicity of PC-3PEc cells as compared with that of wtPC-3 cells.

The effect of the absence of the endogenous IGF-1Ec and, therefore, of PEc, in the tumor was determined by silencing the IGF-1Ec isoform in mPC-3 cells (Supplementary Figure S5A). The silencing of the IGF-1-Ec isoform in the PC-3 cells did not affect their mature IGF-1 levels (Supplementary Figure S5B), their cellular proliferation or their cell cycle (results not shown). However, the subcutaneous inoculation of the IGF-1Ec KD PC-3 cells resulted in the detection of palpable tumors 10 wks following inoculation and in a statistically significant lower rate of carcinogenesis compared with the mPC-3 cells, (two out of 10 mice developed cancer [20%] versus 13 out of 15 [86%] respectively, p < 0.0001). Tumors resulted after the inoculation of IGF-1Ec KD PC-3 cells presented a similar pattern of expression in the majority of the prostate cancer and mesenchymal markers examined, with the mPC-3 tumors as documented by immunohistochemistry (Figure 5C).

Association of Ec Peptide with Prostate Cancer Metastasis

Subcutaneous injection of mPC-3 cells in SCID mice is associated mainly with lymph node metastases (18). To more directly assess the metastatic potential conferred by the PEc, we further expanded our analysis to include nonmetastatic human prostate cells HPrEC, in which the PEc peptide was overexpressed (HPrECPEc cells). The HPrEC cells used in this study were immortalized by the introduction of the SV-40 large T antigen and of the hTERT (these cells were kindly donated by William Hahn, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) (19). Although immortalized, these cells have not been reported to produce metastases.

The HPrECPEc cells (Figures 6A, B) presented an increased rate of cell growth compared with the immortalized wtHPrEC cells after 24 and 48 h of plating (p < 0.001 and p = 0.002 respectively) (Figure 6C), they also presented an increased P ERK1/2 activity, similar to the one obtained after the administration of exogenous Ec peptide to the mHPrEC cells (Figure 6D).

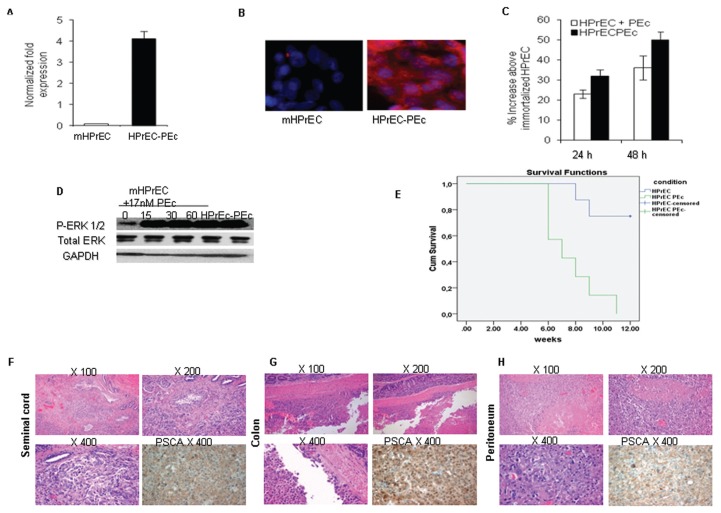

Figure 6.

Association of PEc with metastases. (A) qRT-PCR analysis indicated a significant increase of PEc expression in HPrEC-PEc cells compared with mHPrEC cells, (reference gene: GAPDH) (Student t test, P < 0.001, n = 3). (B) Similar results were observed by immunofluorescence analysis. (C) The growth rate was significantly induced as assessed by MTT assay, in HPrEC-PEc cells and in mHPrEc cells after the exogenous administration of PEc (17 nmol/L) at 24 and 48 h, as compared with the untreated immortalized mHPrEC cells (p < 0.001 in both cases, Student t test, n = 3. Error bars refers to SD). (D) PEc administration induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in immortalized mHPrEC cells, while the immortalized HPrEC-PEc cells possessed constantly activated ERK1/2 (Western blot). (E) Kaplan Meier survival analysis of orthotopically injected SCID mice with mHPrEC or HPrEC-PEc cells. The mice injected with HPrEC-PEc cells (seven) presented a statistically significant decrease in survival at 12 wks compared with the mice injected with immortalized HPrEC cells (nine) (P < 0.002) (Cum. Survival: cumulative survival). (F,G,H) Orthotopic injections of HPrEC-PEc cells in SCID mice were associated with metastases in proximal tissues (seminal cord, colon, peritoneum).

The immortalized HPrEC and HPrECPEc cells were then orthotopically injected into SCID mice. All the mice injected with the HPrECPEc cells died within 12 wks, showing a remarkable increase in the mortality rate as compared with the controls (Figure 6E). Five out of seven SCID mice that were orthotopically injected with the immortalized HPrECPEc cells presented metastases in proximal regions to the prostate: four in the seminal cord/sperm duct; two in the colon; and one in the peritoneum as determined by hematoxylin and eosin staining and expression of PSCA (35) at the regions of metastases (Figures 6F–H). Mice injected with the immortalized mHPrEC did not present metastases.

DISCUSSION

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in elderly men. There are no curative therapies for metastatic prostate cancer. The most common treatment for recurrent disease is surgical or medical castration. However, most commonly, patients progress and develop castration resistant, metastatic growth (36–38).

In this study, we have documented that the Ec peptide (PEc), the 24-amino acid COO– terminal of the IGF-1Ec isoform, is a key molecule in prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Our data suggests that the endogenous overproduction of PEc in PC-3 cells is associated with increased ERK1/2-driven proliferation (similar to the exogenous administration of PEc) and the formation of larger tumors in SCID mice as compared with those generated by the mPC-3 cells. Furthermore, the fact that PEc becomes extracellular and its biological effects are inhibited by the anti-IGF-1Ec antibody, suggests an autocrine/paracrine mode of action. The importance of PEc in tumor growth and progression also was indicated by the inoculation of PC-3 IGF-1Ec KD cells, where only two out of 10 (20%) mice developed palpable tumors ten weeks after the subcutaneous injection.

Our evidence also suggests that PEc expression is associated with the EMT phenomenon. Administration of exogenous PEc in mPC-3 cells, as well as PEc overexpression and secretion of PC-3PEc cells, induced vimentin and suppressed E-cadherin expression. These in vitro results were consistent in the mPC-3- and PC-3PEc-induced tumors in SCID mice. In addition, although IGF-1 induces the EMT in a fashion that involves ERK1/2 activation and ZEB1 expression via the IGF-1R, PEc seems to cause the same effect, but using an IGF-1R independent mechanism.

Further in vivo evidence for the involvement of the PEc in the prostate cancer metastatic process came by the orthotopic injection of immortalized HPrEcPEc cells into SCID mice where four out of seven mice presented metastases in proximal tissues.

These results concur with those obtained by the immunohistochemical analysis of tumors from prostate cancer patients, where the IGF-1Ec isoform was found to be positively associated with prostate cancer stage and grade.

These observations provide new insights in prostate cancer biology, according to which, the E peptide (PEc) resulting from the proteolytic cleavage of the IGF-1Ec isoform induces prostate cancer progression, metastasis and repair (Figure 7). According to this, the Ec peptide may be an attractive candidate to target to prostate cancer treatment without affecting the actions of the mature IGF-1.

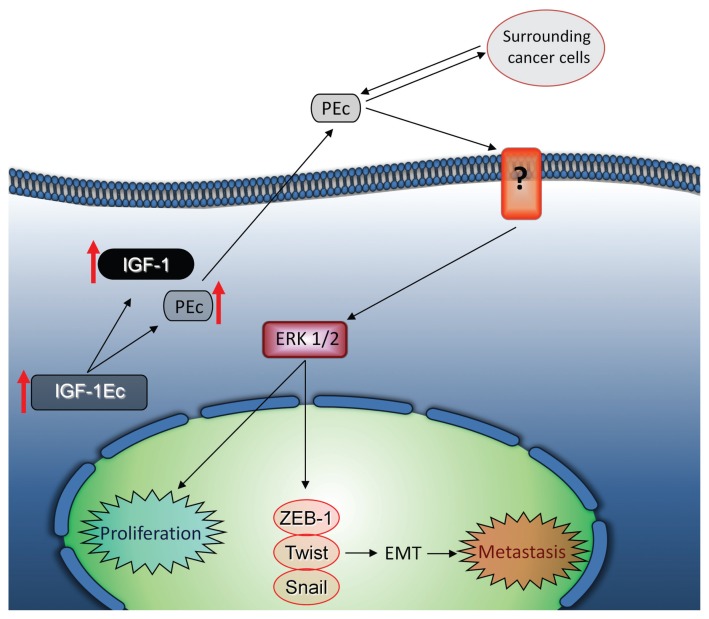

Figure 7.

Mode of action of PEc. PEc is secreted from prostate cancer cells acting in an autocrine and/or paracrine manner, and stimulates prostate cancer cell growth by activating ERK1/2 via an IGF-1R-, IR- and IGF-1R/IR-independent mechanism and induces EMT via ZEB1 expression, inducing prostate cancer metastatic ability.

Supplemental Data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Professors Hahn, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts for the kind donation of the immortalized HPrEC cells and Kotsinas Athanasios, Consoulas Chris and Sideridou Maria and Chris Adamopoulos, from Athens Medical School, National and Kapodestrian University of Athens, for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

DISCLOSURE

The MRM was performed as a fee for service in the Center de Recherche Protéomique, CHUL, G1V 4G2, Quebec, (Quebec) Canada.

Cite this article as: Armakolas A, et al. (2015) Oncogenic role of the Ec peptide of the IGF-1Ec isoform in prostate cancer. Mol. Med. 21:167–79.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilmour RS. The implications of insulin-like growth factor mRNA heterogeneity. J Endocrinol. 1994;140:1–3. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delany AM, Pash JM, Canalis E. Cellular and clinical perspectives on skeletal insulin-like growth factor I. J Cell Biochem. 1994;55:328–33. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240550309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai Z, Wu F, Yeung EW, Li Y. IGF-IEc expression, regulation and biological function in different tissues. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2010;20:275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matheny RW, Jr, Nindl BC, Adamo ML. Minireview: Mechano-growth factor: a putative product of IGF-I gene expression involved in tissue repair and regeneration. Endocrinology. 2010;151:865–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armakolas A, et al. Preferential expression of IGF-1Ec (MGF) transcript in cancerous tissues of human prostate: evidence for a novel and autonomous growth factor activity of MGF E peptide in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2010;70:1233–42. doi: 10.1002/pros.21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milingos DS, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1Ec (MGF) expression in eutopic and ectopic endometrium: characterization of the MGF E-peptide actions in vitro. Mol Med. 2011;17:21–8. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins JM, Goldspink PH, Russell B. Migration and proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells is stimulated by different regions of the mechano-growth factor prohormone. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:1042–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui H, Yi Q, Feng J, Yang L, Tang L. Mechano growth factor E peptide regulates migration and differentiation of BMSCs. J Mol Endocrinol. 2014;52:111–20. doi: 10.1530/JME-13-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fornaro M, et al. Mechano Growth Factor peptide, the COOH terminus of unprocessed insulin-like growth factor 1, has no apparent effect on muscle myoblasts or primary muscle stem cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306:E150–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00408.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brisson BK, Barton ER. Insulin-like growth factor-I E-peptide activity is dependent on the IGF-I receptor. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenta R, Sotiriou E, Pitulis N, Thyphronitis G, Koutsilieris M. Prostate cancer cell survival pathways activated by bone metastasis microenvironment. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2005;5:135–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenta R, Sourla A, Lembessis P, Luu-The V, Koutsilieris M. Bone microenvironment-related growth factors, zoledronic acid and dexamethasone differentially modulate PTHrP expression in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37:593–601. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenta R, Tiblalexi D, Sotiriou E, Lembessis P, Manoussakis M, Koutsilieris M. Bone microenvironment-related growth factors modulate differentially the anticancer actions of zoledronic acid and doxorubicin on PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2004;59:120–31. doi: 10.1002/pros.10363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolis G, et al. Suppression of testicular steroidogenesis by the GnRH agonistic analogue Buserelin (HOE-766) in patients with prostatic cancer: studies in relation to dose and route of administration. J Steroid Biochem. 1983;19:995–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(83)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koutsilieris M, et al. Objective response and disease outcome in 59 patients with stage D2 prostatic cancer treated with either Buserelin or orchiectomy. Disease aggressivity and its association with response and outcome. Urology. 1986;27:221–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(86)90278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koutsilieris M, Rabbani SA, Bennett HP, Goltzman D. Characteristics of prostate derived growth factors for cells of the osteoblast phenotype. JCI. 1987;80:941–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI113186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koutsilieris M, Rabbani SA, Goltzman D. Effects of human prostatic mitogens on rat bone cells and fibroblasts. J Endocrinol. 1987;115:447–54. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1150447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bastidel C, Bagnis C, Mannoni P, Hassoun J, Bladoul F. A Nod Scid mouse model to study human prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Dis. 2002;5:311–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger R, et al. Androgen-induced differentiation and tumorigenicity of human prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8867–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koutsilieris M, Rabbani SA, Bennett HP, Goltzman D. Characteristics of prostate-derived growth factors for cells of the osteoblast phenotype. JCI. 1987;80:941–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI113186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham TR, et al. IGF-1-dependent upregulation of ZEB1 expression drives EMT in human prostate cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2479–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhau HE, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in human prostate cancer: lessons learned from ARCaP model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:601–10. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, ZEB and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev. 2007;7:415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohira T, et al. WNT7a induces E-cadherin in lung cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10429–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734137100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spaderna S, et al. A transient, EMT-linked loss of basement membranes indicates metastasis and poor survival in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:830–40. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grooteclaes M, Frisch S. Evidence for a function of CtBPin epithelial gene regulation and anoikis. Oncogene. 2000;19:3823–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chinnadurai G. CtBP, an unconventional transcriptional corepressor in development and oncogenesis. Mol Cell. 2002;9:213–24. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aigner K, et al. The transcription factor ZEB1 (yEF1) promotes tumour cell dedifferentiation by repressing master regulators of epithelial polarity. Oncogene. 2007;26:6979–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:563–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantel K, Brakenhoff RH. Dissecting the metastatic cascade. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:448–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talbot LJ, Bhattacharya SD, Kuo PC. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, the tumor microenvironment, and metastatic behavior of epithelial malignancies. Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;3:117–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dave N, et al. Functional cooperation between Snail 1 and Twist in the regulation of ZEB1 expression during epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12024–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.168625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sideridou M, et al. Cdc6 expression represses E-cadherin transcription and activates adjacent replication origins. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:1123–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paine-Murrieta GD, et al. Human tumor models in the severe combined immune deficient (scid) mouse. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;40:209–14. doi: 10.1007/s002800050648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tran CP, Lin C, Yamashiro J, Reiter ER. Prostate stem cell antigen is a marker of late intermediate prostate epithelial cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2002;1:113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB. Prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;2003;349:366–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strope AS, Andriole LG. Prostate cancer screening: current status and future perspectives. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;9:487–93. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guillonneau B. Prostate cancer: New treatments for localized tumours—what matters first? Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:414–5. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.