Introduction

Although an uncommon pathogen causing clinical disease, Nocardia species are ubiquitous microorganisms found in the environment with over 50 species identified [1]. The majority of Nocardia infections occur as pulmonary infections following inhalation in immunocompromised hosts, including patients with HIV, chronic corticosteroids, and persons taking immunosuppression after transplantation [2]. Less commonly, immunocompetent hosts can develop a cutaneous form of Nocardia infection after a traumatic percutaneous inoculum [3]. Disseminated disease often involves the brain, lungs and skin [4]. Despite the low incidence of Nocardia infection in both groups, several studies have demonstrated the need for a high degree of clinical suspicion in at-risk patients, where microbiologic diagnosis is delayed by slow bacterial growth in culture. Suspect patients require aggressive treatment given the high mortality rate associated with these infections [5–7].

The genus Nocardia contains relatively few species that have been shown to be truly pathogenic in humans [8]. Nocardiosis is often misdiagnosed because of its rarity and non-specific clinical picture. Some of the more common species causing human disease include N. nova, N. brasiliensis, N. farcinia and N. aesteroides, the causative organism in this case [2]. These are most commonly found in sand, soil, dust, stagnant water and decaying vegetation [2]. Nocardia are aerobic partially acid-fast Gram positive bacteria which form thin branching rods and can be cultured on routine culture media such as blood agar or chocolate agar [8]. These bacteria are notoriously difficult to identify in culture as they require a minimum of 48–72 h to grow before colonies are evident, and in some cases can take as long as 14 days to appear. If the distinctive Gram positive filamentous, branching rods characteristic of Nocardia are not seen on Gram stain of a clinical sample, the culture may be discarded before Nocardia can be grown and identified. With a high degree of clinical suspicion and prolonged incubation of the culture, the organism is more often correctly identified [7].

In this report, we present a patient on long term corticosteroid treatment for an ANCA associated small vessel vasculitis that developed a necrotizing soft tissue infection of the upper extremity with cultures demonstrating Nocardia aesteroides. To our knowledge, there have been few reported cases of a Nocardia infection of the hand and none that has presented as a necrotizing soft tissue infection.

Case Report

The patient is a 79-year-old female with a past medical history significant for an ANCA associated small vessel vasculitis for which she has taken five milligrams of Prednisone daily for the past ten years who presented with pain of the left hand, wrist, and forearm that had been progressively worsening for two weeks. Her symptoms initially developed after she received a steroid injection in her first extensor compartment for presumed DeQuervain’s tendonitis by her rheumatologist. Subsequently, she developed erythema and subcutaneous nodules of her left wrist and forearm. She was seen at an outside emergency room where she was prescribed a one week course of oral Cephalexin.

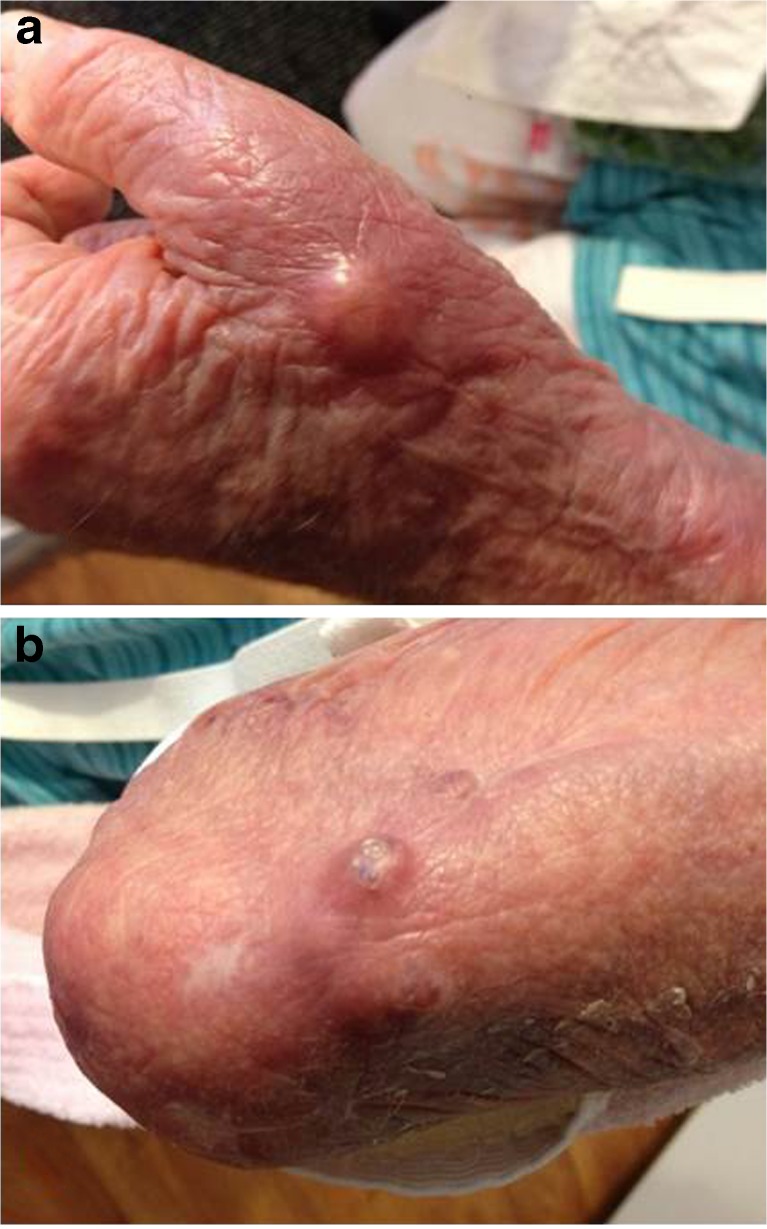

After completing the course of antibiotics, the patient developed progressive erythema and swelling over her entire extremity, from her axilla to the fingertips. An upper extremity ultrasound was negative for deep venous thrombosis, and cultures were obtained from the subcutaneous nodule in her dorsal radial wrist, which demonstrated Gram positive rods. She was referred to our emergency room for further evaluation. At the time of her arrival, she was lethargic with streaking erythema and swelling of her extremity, as well as fluctuance of her dorsal radial wrist. (Fig. 1) Her WBC count in the emergency room was 30,000 / mm3 with 4 % bandemia. She was started on broad spectrum antibiotics (Vancomycin, Clindamycin, Imipenem) and was brought urgently to the operating room by the emergency surgery service for debridement of presumed left upper extremity necrotizing fasciitis.

Fig. 1.

Initial presentation: a hand and b forearm nodules

An incision was made over the dorsal radial wrist at the site of the cutaneous nodule, and purulent drainage was encountered with frankly necrotic muscle of the second extensor compartment. A dorsal forearm incision was made with return of turbid fluid and the friable dorsal skin with cutaneous lesions was resected. The hand surgery service was then consulted for further evaluation and dorsal hand incisions were made to evaluate the dorsal subcutaneous space and compartments of the hand. Additional debridement was performed along the dorsal radial aspect of the wrist until bleeding, viable tissue was encountered (Fig. 2). A non-occlusive dressing and splint were applied.

Fig. 2.

Defect after initial debridement

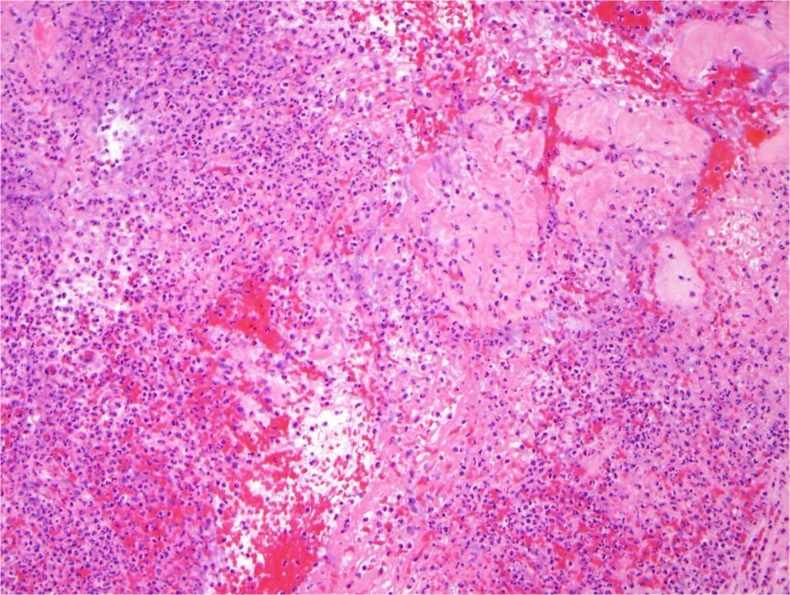

The Gram stain initially demonstrated thin, branching Gram positive rods that were visible on modified acid-fast stain. After several days, cultures grew Nocardia asteroides resistant to penicillins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides. Fortunately, the isolate was susceptible to carbopenems and Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole. Antibiotic resistances were determined by the disk method while the MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) of this organism was determined by the broth dilution method. The pathology from the specimens taken from the subcutaneous tissue and fascia of her left arm and wrist at the time of her initial operation demonstrated hemorrhagic and focally necrotic soft tissue consistent with a necrotizing soft tissue infection (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Representative pathology slides demonstrating a necrotizing soft tissue infection with neutrophilic infiltrate

The patient returned to the operating room two days later for additional debridement, and her incisions were partially closed. A wound V.A.C. (Kinetic Concepts Inc., San Antonio, TX) was applied to the dorsal forearm wound, and she subsequently returned to the operating room for skin grafting. (Fig. 4) She underwent chest and head imaging to rule out disseminated disease and these studies did not demonstrate additional pathology. Blood and sputum cultures for Nocardia were also negative and her antibiotic regimen was narrowed to Imipenem alone. The remainder of her hospital course was uneventful, and she ultimately received a three week course of Imipenem followed by two months of Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, and her wounds healed without recurrent infection.

Fig. 4.

a Skin graft closure of the dorsal forearm wound and b 2 week postop clinic visit

Discussion

Although an extremely common bacterium in the environment, Nocardia species are rarely pathogenic in humans. Two-thirds of cases occur in immunocompromised hosts in the form of pulmonary infections [1, 2]. However, cutaneous Nocardia infection after a traumatic percutaneous inoculum has also been described [3]. In this case, the patient’s infection was most likely attributable to direct inoculation via local steroid injection or through environmental exposure.

Nocardia infections have been reported more frequently in patients with cell-mediated immunodeficiency such as patients with HIV, patients who have received an organ transplant, or patients taking long term corticosteroids. Several studies have reported that the incidence of Nocardia infections in these groups is between 140 to 340 times higher than in the general population [3, 9]. Nocardia species rarely cause necrotizing soft tissue infections, which are most commonly caused by Gram positive cocci such as Staphyloccoccus aureus and Streptococcal species, and anaerobes, most notably Clostridium species [10, 11].

Most cases of primary cutaneous Nocardia infection are localized and manifest as an acute superficial infection or chronic mycetoma [8]. Superficial infections often present with small nodular or pustular lesions, which may progress to cellulitis or abscess formation [8]. It is likely that the initial small nodular lesions which developed in this patient after the steroid injection represented a superficial infection. She was then started on a one week course of oral antibiotics, which were ineffective against Nocardia, allowing her disease to progress to a necrotizing infection. Most authors recommend between a one and three month course of antibiotics following Nocardia infection, which is consistent with our patient’s treatment following definitive diagnosis [2]. However, depending on the seriousness of infection and the clinical response, a longer duration of treatment may be considered.

Given the low incidence of Nocardia infections, the best therapeutic agent and duration have not been well established in clinical trials. Sulfonamides have been the agent of choice for over 60 years, but there remains a high degree of recurrence and mortality associated with monotherapy in cases of severe infection [2]. Additionally, these antibiotics commonly cause gastrointestinal intolerance and allergic reactions. As a result, for life-threatening disease, some authors recommend initial combination dual or triple therapy with a sulfonamide, a beta lactam and an aminoglycoside [2]. Many authors advocate for the use of aggressive therapy when Nocardia infection is suspected because diagnosis can be delayed due to slow growth of the organism in culture media, which can take up to 14 days to confirm; this is a time period that is often longer than plates are kept in most clinical microbiology laboratories [5–7].

This patient’s state of chronic immunosuppression, combined with manipulation of the wrist with steroid injection, most likely allowed for the inoculation of Nocardia and the progression of a local cellulitis into a necrotizing soft tissue infection. To our knowledge, there have been few reported cases of a Nocardia infection in the hand and there have been no reports of necrotizing soft tissue infection of the upper extremity caused by a traumatic inoculation. In this case, early and serial debridement, combined with appropriate antibiotics and wound closure with skin grafting, helped to eradicate her infection and preserve her upper extremity.

Acknowledgments

None

Sources of Funding

No funding supported this research.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

The authors, Joseph A. Ricci, M.D., Ana A. Weil M.D., M.P.H. and Kyle R. Eberlin, M.D. are in compliance with the ethics requirements. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement on Informed Consent

No patient identifying information has been published in this research paper.

Conflict of Interest

Joseph A. Ricci, M.D., Ana A. Weil M.D., M.P.H. and Kyle R. Eberlin, M.D. have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This research was not supported by any source of funding.

References

- 1.Yamagata M, Hirose K, Ikeda K, et al. Clinical characteristics of Nocardia infection in patients with rheumatic diseases. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:818654. doi: 10.1155/2013/818654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerner PI. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891–903. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosman Y, Grossman E, Keller N, et al. Nocardiosis: a 15-year experience in a tertiary medical center in Israel. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardak E, Yigla M, Berger G, et al. Clinical spectrum and outcome of Nocardia infection: experience of 15-year period from a single tertiary medical center. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343:286–290. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31822cb5dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peleg AY, Husain S, Qureshi ZA, et al. Risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcome of Nocardia infection in organ transplant recipients: a matched case–control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1307–1314. doi: 10.1086/514340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saubolle MA, Sussland D. Nocardiosis: review of clinical and laboratory experience. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4497–4501. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4497-4501.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodiuk-Gad R, Cohen E, Ziv M, et al. Cutaneous nocardiosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1380–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filice GA. Nocardiosis in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection, transplant recipients, and large, geographically defined populations. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;145:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott D, Kufera JA, Myers RA. The microbiology of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Am J Surg. 2000;179:361–366. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontes RA, Jr, Ogilvie CM, Miclau T. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:151–158. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]