Abstract

Objective

The authors surveyed the prevalence and the clinical character of lumbar disc herniation (LDH) in Korean male adolescents, and the usefulness of current conscription criteria.

Methods

The data of 39,673 nineteen-year-old males that underwent a conscription examination at the Seoul Regional Korean Military Manpower Administration (MMA) from October 2010 to May 2011 were investigated. For those diagnosed as having lumbar disc herniation, prevalences, subject characteristics, herniation severities, levels of herniation, and modified Korean Oswestry low back pain disability scores by MMA physical grade were evaluated. The analysis was performed using medical certificates, medical records, medical images, and electromyographic and radiologic findings.

Results

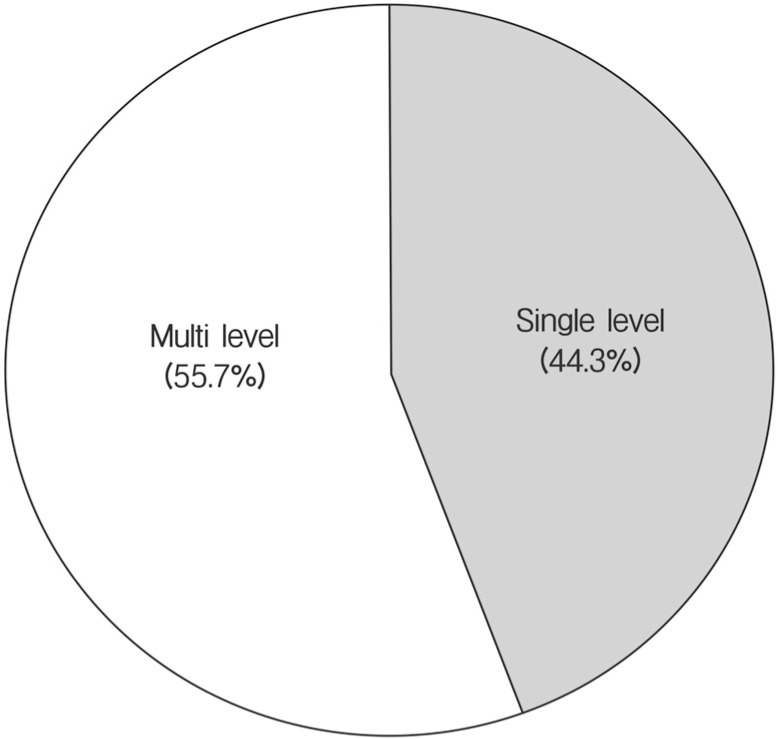

The prevalence of adolescent LDH was 0.60%(237 of the 39,673 study subjects), and the prevalence of serious adolescent LDH with thecal sac compression or significant discogenic spinal stenosis was 0.28%(110 of the 39,673 study subjects). Of the 237 adolescent LDH cases, 105 (44.3%) were of single level LDH and 132 (55.7%) were of multiple level LDH, and the L4-5 level was the most severely and frequently affected. Oswestry back pain disability scores increased with herniation severity (p<0.01), and were well correlated with MMA grade.

Conclusions

In this large cohort of 19-year-old Korean males, the prevalence of adolescent LDH was 0.60% and the prevalence of serious adolescent LDH, which requires management, was relatively high at 0.28%. MMA physical grade was confirmed to be a useful measure of the disability caused by LDH.

Keywords: Lumbar disc herniation, Adolescent, Prevalence, Conscription

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a common disorder among adults with a degenerative spinal change, and has a reported lifetime occurrence as high as 40%10). However, the true frequency of this condition in adolescents has not been precisely defined, though it is generally believed to be much lower than in adults, because adolescents tend to have healthier spines and a more robust physiological nature. Studies conducted on LDH in adolescents during recent years have substantially increased our understanding of this entity, but nevertheless, information on adolescent LDH is sparse. Moreover, to ensure a fair means of conducted conscription in Korea, an understanding of the characteristics of LDH in adolescent males is needed. This study was undertaken to determine the prevalence and the clinical character of lumbar disc herniation in a large cohort of 19-year-old Korean males and to determine the usefulness of current conscription criteria.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

All Korean men are examined for conscription by the Military Manpower Administration at age of 19. This cross-sectional survey was conducted at the Military Manpower Administration from total of 39,673 males at age of 19 year old in Seoul from October 2010 to May 2011. We retrospectively reviewed all office charts of who submitted medical certificate for adolescent LDH with medical records and imaging test. When clinical manifestations did not correlate with radiological findings, all medical certificates for adolescent LDH with medical records and imaging test findings (MRI or CT) and electromyographic results were retrospectively reviewed. In addition, the modified Korean Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire was administered to all study subjects. One radiologist and one neurosurgeon jointly made diagnostic decisions.

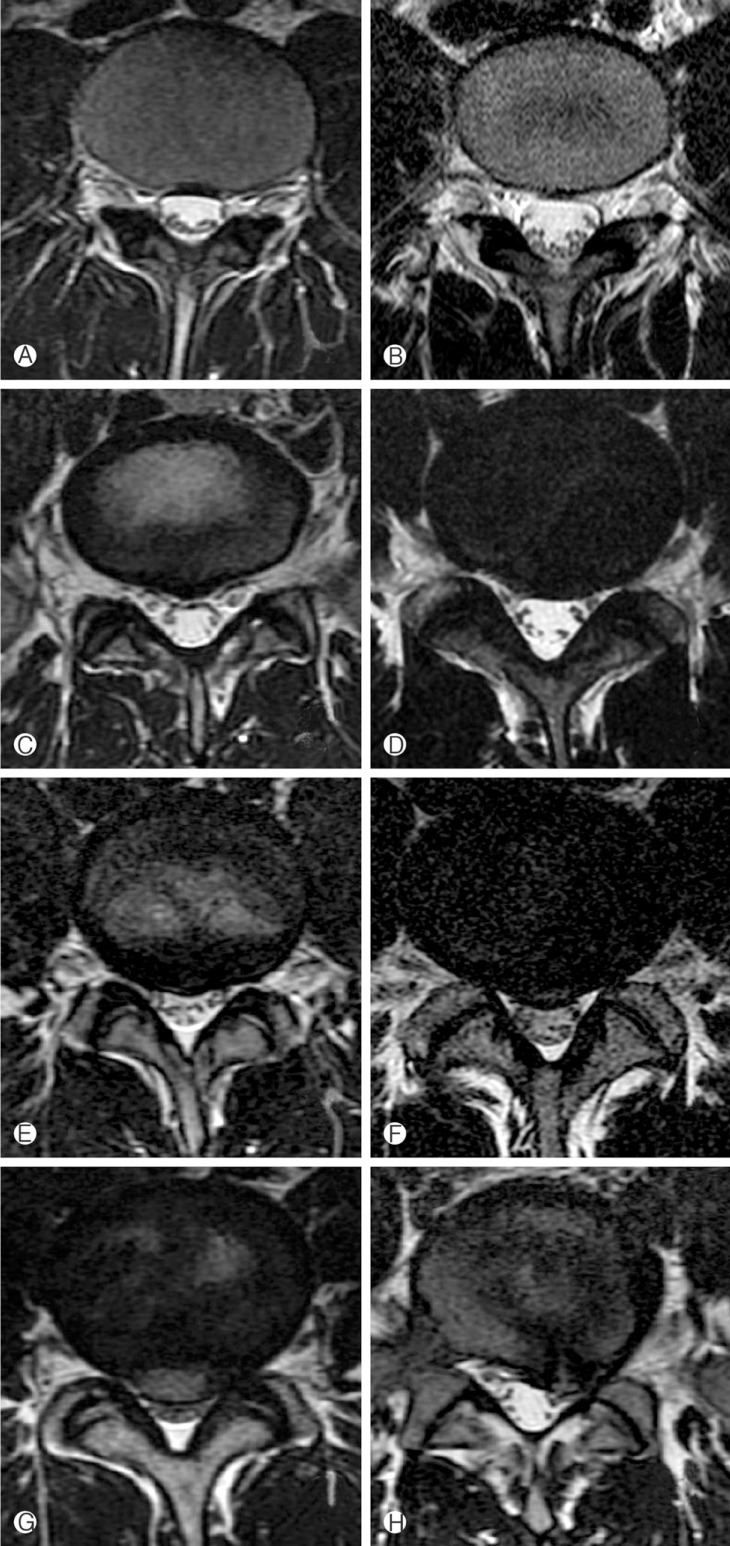

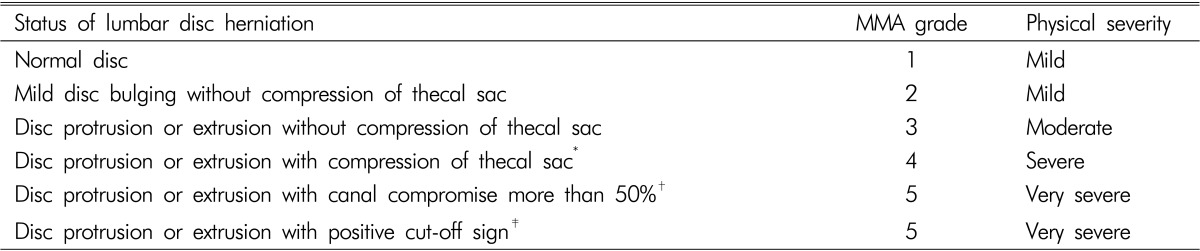

We classified adolescent LDH into four groups of herniation severity as is required by the guideline issued by the Korean military directorate, as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. According to the guideline, medical conditions are assigned to seven Military Manpower Administration (MMA) physical grades. Normal disc with no signal change in MRI and no disrupted disc material was defined as physical grade 1. Mild disc bulging without compression of thecal sac was considered as grade 2 (Fig. 1A, 1B). Disc protrusion or extrusion without compression of thecal sac was classified to grade 3 (Fig. 1C, 1D). Disc protrusion or extrusion with compression of thecal sac was considered to grade 4 (Fig. 1E, 1F). If thecal sac compression was ambiguous, additional electoromyogram test was applied to examinees. A positive electromyogram test was defined as matched radiculopathy finding in terms of the level suspicious for herniation.; Disc protrusion or extrusion with canal compromise more than 50% at the mid-sagittal diameter (front to back) in the same plane was defined as grade 5 (Fig. 1G). Disc protrusion or extrusion with positive cut-off sign, the loss of neuromuscular signal at the level of interest identified by imaging, was also classified as grade 5 (Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1. Images of categories of adolescent herniated lumbar discs in accordance with the guideline issued by the Korean military medical directorate. Mild disc bulging without compression of thecal sac was considered as grade 2 (A, B). Disc protrusion or extrusion without compression of thecal sac was classified to grade 3 (C, D). Disc protrusion or extrusion with compression of thecal sac was considered to grade 4 (E, F). Disc protrusion or extrusion with canal compromise more than 50% at the mid-sagittal diameter in the same plane was defined as grade 5 (G). Disc protrusion or extrusion with positive cut-off sign, the loss of neuromuscular signal at the level of interest identified by imaging, was also classified as grade 5 (H).

Table 1. Classification of adolescent herniated lumbar disks as required by guideline issued by the Korean military medical directorate.

*A positive electromyogram test was defined as matched radiculopathy finding in terms of the level suspicious for herniation; †spinal canal stenosis was defined as the narrowing of the spinal canal by >50% of the mid-sagittal diameter (front to back) in the same plane; ‡cut-off was defined as the loss of neuromuscular signal at the level of interest identified by imaging.

For the purposes of the present study, grade 1-2 was considered mild herniation, grade 3 as moderate herniation, grade 4 as severe herniation, grade 5-6 as very severe herniation, and grade 7 as considered as the necessary of recheck about the physical condition. A history of simple discectomy or of a spinal procedure was not considered, and preoperative herniation severities were used to confirm MMA grades. Subjects with other spinal diseases, such as, ankylosing spondylitis, spondylolisthesis, spondylolysis, Shermann's nodules, limbus fractures, lumbarization, and scoliosis, were excluded from the study.

The prevalences of adolescent LDH were analyzed according to the guideline issued by the Korean military directorate herniation severities. Level of herniation distribution was also determined. The relation between Modified Korean Oswestry low back pain scores and MMA grades was analyzed. Statistical significances between herniation severity groups were examined by simple linear regression analysis. Tests were considered significant when p-values were <0.05, and the analysis was conducted using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). This study was conducted with the approval of the Military Manpower Administration in Seoul.

RESULTS

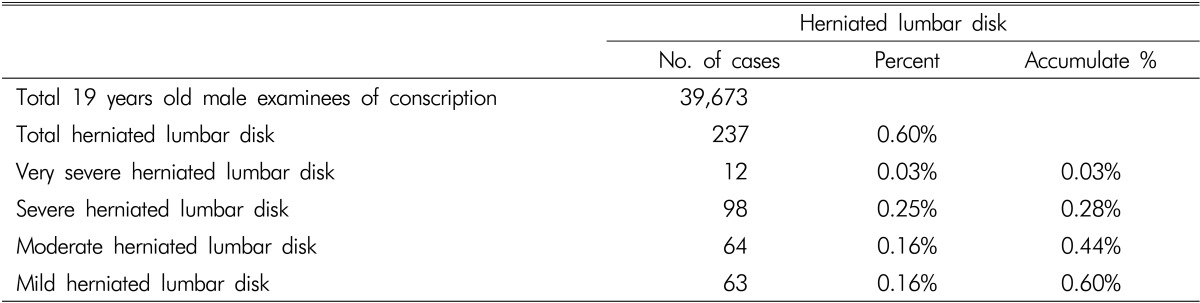

The results of this study are summarized in Table 2. Of the 39,673 study subjects, 237 were diagnosed as having adolescent lumbar disk herniation (LDH), and thus, the estimated prevalence of adolescent LDH in our population was 0.60%. The prevalence of very severe LDH was 0.03%, of severe LDH was 0.25%, and of moderate and mild LDH was 0.16%. The estimated prevalence of serious adolescent LDH with thecal sac compression or significant discogenic spinal stenosis was 0.28%. In this study, 9 cases were examined after the surgery; 7 cases underwent on an open discectomy, 1 case underwent on artificial disc insertion, and 1 pedicle screw fixation.

Table 2. The prevalence of a herniated lumbar disk in 19-year-old males.

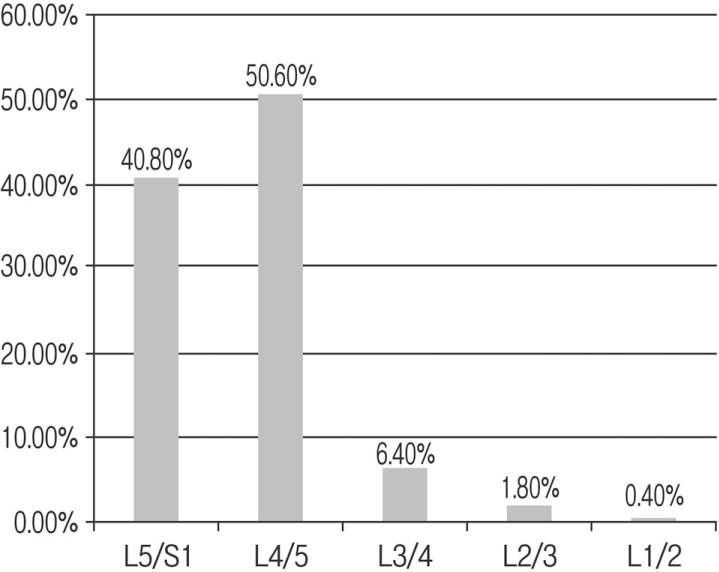

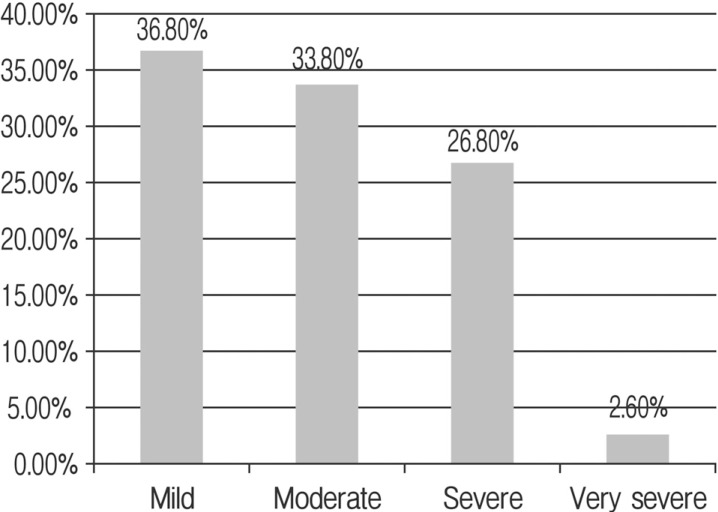

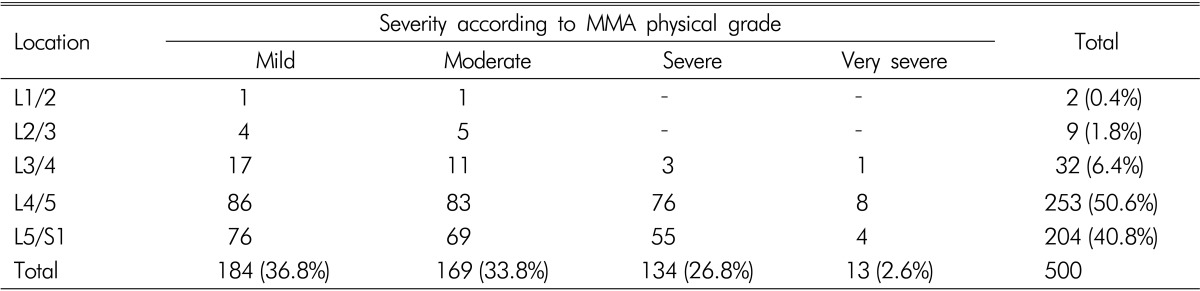

One thousand one hundred eighty-five disc levels were investigated during the study. Out of the 237 adolescent LDH cases, 105 cases (44.3%) had single level LDH and 132 cases (55.7%) had multiple level LDH(Fig. 2). Out of the 1185 disc levels, 500 were checked for disc status for reasons ranging from bulging to severe spinal canal stenosis. The distribution of the 500 disc levels is shown in Table 3. According to the affected disc level, the distribution was shown in L5-S1 as 40.8%, L4-5 as 50.6%, L3-4 as 6.4%, L2-3 as 1.8%, and L1-2 as 0.4%(Fig. 3). According to severity of disc, the distribution was checked as 36.8% in mild herniation, 33.8% in moderate herniation, 26.8% in severe herniation, and 2.6% in very severe herniation (Fig. 4). In terms of herniation severity, severe and very severe herniation were present at 29.4% of affected levels; the L4-5 level was the most frequently affected site followed by L5-S1 (50.6% and 40.8%, respectively).

Fig. 2. Single and multilevel percentage of 1185 disc levels among 237 19-year-old male examinees.

Table 3. Distribution and severity of herniated lumbar disc segments for the 237 herniated lumbar disc cases (1,185 disc segments).

Fig. 3. Disc level distribution of herniated lumbar disc segments for the 237 herniated lumbar disc cases (1185 disc segments).

Fig. 4. Distribution of herniated lumbar disc segments for the 237 herniated lumbar disc cases according to disc severity.

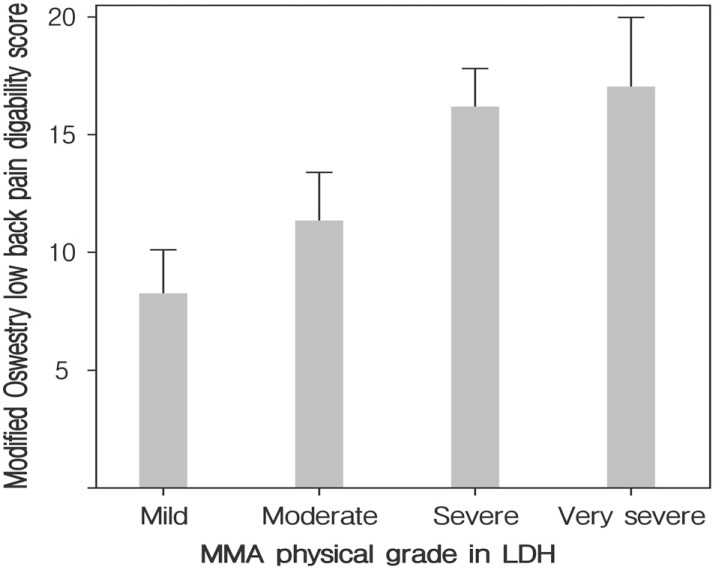

Modified Korean Oswestry low back pain disability scores for MMA physical grades are summarized in Fig. 5. Oswestry scores increased with MMA severity, that is, from 8.3±8.3 in the mild herniation group, 11.3±7.9 in the moderate herniation group, 16.1±9.7 in the severe herniation group, to 17.0±8.1 in the very severe herniation group. Simple linear regression analysis showed that the P-value was <0.01.

Fig. 5. Relation between modified Korean Oswestry low back pain disability scores and MMA physical grades.

DISCUSSION

The first report of a herniated nucleus pulposus in a child was published in 1934, and the first report of surgical treatment in a child (a 12-year-old boy) was issued in 19456,32). Clinical presentations of adolescent LDH are generally similar of adults25,26). However, up to 90% of adolescent patients have a positive straight-leg raise test7,12), which differentiates adolescent and adult LDH, and is explained by finding that children and adolescents tend to have greater nerve root tension than adults20). Furthermore, this is often accompanied by neurological symptoms, such as, numbness and weakness5,11,24).

In the past, trauma was considered the main etiological factor of the development of adolescent LDH2,7,34). However, whereas trauma in adults is mostly often related to lifting or twisting, any severe physical stress on the lumbosacral spine may primarily lead to the onset of symptoms in adolescents. These stresses include a fall, heavy lifting, and extreme flexion-extension, such as, those related to participation in competitive sports. Familial disc disease is considered to be another etiologic factor predisposing adolescent LDH5,20,28,30), and separation of the posterior ring apophysis of an adjacent vertebral body can sometimes accompany LDH1,4).

Prevalence studies have reported that 0.5-6.8% of all patients hospitalized for LDH are pediatric cases3,7,8,13,14,16,21,27,31). However, the real prevalence of adolescent LDH is difficult to establish for various reasons, for example, the different age ranges adopted in published series4,13,19,21). A literature review revealed that one previous study addressed the prevalence of Korean adolescent LDH14). This study was also based on examinations of Korean conscriptees, and found a prevalence of intervertebral disc herniation in adolescent aged at 19 years old and younger of 0.5%(382 cases among 77,685 examinees), which concurs our result of 0.60% among 19-year-old male adolescents. On the other hand, the findings of some reports do not support our findings. An epidemiologic study that followed up 12,058 Finnish babies from birth until 28 years of age, showed that no case of confirmed LDH until at age of 15 years and a prevalence of only 0.1-0.2% among 20 years old33). Furthermore, by 28 years of age, 9.5% of males and 4.2% of females were found to have been admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of LDH. These results are quite different to ours, and indicate that a more precise retrospective epidemiologic study is needed.

In the present study, the percentage of disc segments with root compression or significant discogenic spinal stenosis was 29.4% with an incidence of 0.28%. This percentage is similar to that of reported in another study, in which LDH with thecal sac compression or significant discogenic spinal stenosis was found to occur in 29% of disc segments with incidence of 0.28%15). In adult LDH, the prevalence of disc protrusion has been reported to be 16% and 33%23,29). Regarding herniation severity, serious LDH(thecal sac compression or significant discogenic spinal stenosis) has been reported to be more frequently observed in adolescents than in adults.

In this study, the majority of herniations occurred at low lumbar levels or at the lumbosacral junction (50.6% and 40.8%), and only a small percentage of herniations were seen at L3/L4 and above. These percentages are similar to those found in previous conscription studies15,18). In adolescent LDH, multiple level involvement suggests that underlying diathesis contributes to development of disc herniation18), and in the present study, multiple level involvements were observed in 55.7% of our 237 subjects with adolescent LDH.

The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire was developed for multi-center or national spine surgery surveys. The questionnaire can be easily administered and is capable of detecting functional disability in different spinal disorders17,22). It is divided into ten sections selected from a series of experimental questionnaires designed to assess limitations during various activities, such as, pain intensity, personal care (washing, dressing, etc), lifting, walking, sitting, standing, sleeping, sex life, social life, and travelling9). Each section is scored on a 0-5 scale, where 5 represents greatest disability. In the present study, we used the modified Korean Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire, but we excluded questions on sex life, because the study subjects were adolescents. Thus, the maximum score of the modified questionnaire as applied was 45, where scores represent disability.

As shown in Figure 5, modified Korean Oswestry low back pain disability scores increased with herniation severity. According to a previous study9), a score of 0-9 represents minimal disability, 10-18 moderate disability, 19-27 severe disability, and 28-36 a crippled status. In the present study, the mild herniation group corresponded to minimal disability, and the moderate, severe, and very severe herniation groups to moderate disability (mean modified Korean Oswestry low back pain disability scores were 8.3±8.3 in the mild herniation group, 11.3±7.9 in the moderate herniation group, 16.1±9.7 in the severe herniation group, and 17.0±8.1 in the very severe herniation group). Accordingly, Oswestry scores increased with severity, and simple linear regression analysis returned a p value of <0.05 for the relation between the two. So, MMA physical grade was found to be an useful measure of disability due to LDH among adolescent males.

CONCLUSION

In a large cohort of 19-year-old Korean adolescent males in Seoul, Korea, the prevalence of adolescent LDH was found to be 0.60% and the prevalence of serious adolescent LDH, which can require management, was found to be relatively high (0.28%). Multiple levels LDH was slightly more common as 55.7%, and most common affected lesions were not different as the lesions of normal population. MMA physical grade was found to be an accurately measure of disability due to LDH in adolescent males.

References

- 1.Banerian KG, Wang AM, Samberg LC, Kerr HH, Wesolowski DP. Association of vertebral end plate fracture with pediatric lumbar intervertebral disk herniation: value of CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 1990;177:763–765. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.3.2243985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford DS, Garcia A. Herniation of the lumbar intervertebral disc in children and adolescents. JAMA. 1969;210:2045–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgensen SE, Vang PS. Herniation of the lumbar intervertebral disk in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop Scand. 1974;45:540–549. doi: 10.3109/17453677408989177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan DJ, Pack LL, Bream RC, Hensinger RN. Intervertebral disc impingement syndrome in a child: report of a case and suggested pathology. Spine. 1986;11:402–404. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198605000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke NM, Cleak DK. Intervertebral lumbar disc prolapse in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3:202–206. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeOrio JK, Bianco AJ. Lumbar disc excision in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:991–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein JA, Epstein NE, Marc J, Rosenthal AD, Lavine LS. Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation in teenage children: recognition and management of associated anomalies. Spine. 1984;9:427–432. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198405000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein JA, Lavine LS. Herniated lumbar intervertebral disc in teenage children. J Neurosurg. 1964;2:1070–1075. doi: 10.3171/jns.1964.21.12.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O'Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frymoyer JW, Pope MH, Clements JH, Wilder DG, MacPherson B, Ashikaga T. Risk factors in low-back pain. An epidemiological survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:213–218. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198365020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrido E, Humphreys RP, Hendrick EB, Hoffman HJ. Lumbar disc disease in children. Neurosurgery. 1978;2:22–26. doi: 10.1227/00006123-197801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gennuso R, Humphreys RP, Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB, Drake JM. Lumbar intervertebral disc disease in the pediatric population. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:282–286. doi: 10.1159/000120676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto K, Fujita K, Kojimoto H, Shimomura Y. Lumbar disc herniation in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:394–396. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199005000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heithoff KB, Gundry CR, Burton CV, Winter RB. Juvenile discogenic disease. Spine. 1994;19:335–340. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199402000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong CK, Park CK, Park HC, Yoon SH. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of intervertebral disc herniation in adolescence: a study based on examination for conscription. Korean J Spine. 2004;1:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurihara A, Kataoka O. Lumbar disc herniation in children and adolescents: a review of 70 operated cases and their minimum 5-year follow-up studies. Spine. 1980;5:443–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leclaire R, Blier F, Fortin L, Proulx R. A cross-sectional study comparing the Oswestry and Roland-Morris functional disability scales in two populations of patients with low back pain of different levels of severity. Spine. 1997;22:68–71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199701010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee KS, Jeon SS. Analysis of MRI findings of adolescent lumbar disc herniation: comparison with adult lumbar disc herniation findings. J Korean Soc Spine Surg. 2000;7:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luukkonen M, Partanen K, Vapalahti M. Lumbar disc herniations in children: a long-term clinical and magnetic resonance imaging follow-up study. Br J Neurosurg. 1997;11:280–285. doi: 10.1080/02688699746041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui H, Kitagawa H, Kawaguchi Y, Tsuji H. Physiological changes of nerve root during posterior lumbar discectomy. Spine. 1995;20:654–659. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199503150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui H, Terahata N, Tsuji H, Hirano N, Naruse Y. Familial predisposition and clustering for juvenile lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1992;17:1323–1328. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199211000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niskanen RO. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. a two-year follow-up of spine surgery patients. Scand J Surg. 2002;91:208–211. doi: 10.1177/145749690209100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong A, Anderson J, Roche J. A pilot study of the prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration in elite athletes with lower back pain at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:263–266. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozgen S, Konya D, Toktas OZ, Dagcinar A, Ozek MM. Lumbar disc herniation in adolescence. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43:77–81. doi: 10.1159/000098377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papagelopoulos PJ, Shaughnessy WJ, Ebersold MJ, Bianco AJ, Jr, Quast LM. Long-term outcome of lumbar discectomy in children and adolescents sixteen years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:689–698. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parisini P, Di Silvestre M, Greggi T, Miglietta A, Paderni S. Lumbar disc excision in children and adolescents. Spine. 2001;26:1997–2000. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pietilä TA, Stendel R, Kombos T, Ramsbacher J, Schulte T, Brock M. Lumbar disc herniation in patients up to 25 years of age. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2001;41:340–344. doi: 10.2176/nmc.41.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postacchini F, Lami R, Pugliese O. Familial predisposition to discogenic low back pain: an epidemiologic and immunogenetic study. Spine. 1988;13:1403–1406. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198812000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadnik TW, Lee RR, Coen HL, Neirynck EC, Buisseret TS, Osteaux MJ. Annular tears and disk herniation: prevalence and contrast enhancement on MR images in the absence of low back pain or sciatica. Radiology. 1998;206:49–55. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.1.9423651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varlotta GP, Brown MD, Kelsey JL, Golden AL. Familial predisposition for the herniation of a lumbar disc in patients who are less than twenty-one years old. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wahren H. Herniated nucleus pulposus in a child of twelve years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1945;16:40–42. doi: 10.3109/17453674508988913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamani MH, McEwen GD. Herniation of the lumbar disc in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 1982;2:528–533. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198212000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zitting P, Rantakallio P, Vanharanta H. Cumulative incidence of lumbar disc diseases leading to hospitalization up to the age of 28 years. Spine. 1998;23:2337–2343. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199811010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zucker L, Amacher AL, Eltomey A. Juvenile lumbar discs. Childs Nerv Syst. 1987;3:125–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00271141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]