Abstract

The endoscopic approach for biliary diseases in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy (SAGA) had been generally deemed impractical. However, it was radically made feasible by the introduction of double balloon endoscopy (DBE) that was originally developed for diagnosis and treatments for small-bowel diseases. Followed by the subsequent development of single-balloon endoscopy (SBE) and spiral endoscopy (SE), interventions using several endoscopes for biliary disease in patients with SAGA widely gained an acceptance as a new modality. Many studies have been made on this new technique. Yet, some problems are to be solved. For instance, the mutual unavailability among devices due to different working lengths and channels, and unestablished standardization of procedural techniques can be raised. Additionally, in an attempt to standardize endoscopic procedures, it is important to evaluate biliary cannulating methods by case with existence of papilla or not. A full comprehension of the features of respective scope types is also required. However there are not many papers written as a review. In our manuscript, we would like to evaluate and make a review of the present status of diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography applying DBE, SBE and SE for biliary diseases in patients with SAGA for establishment of these modalities as a new technology and further improvement of the scopes and devices.

Keywords: Double balloon endoscopy, Single balloon endoscopy, Spiral endoscopy, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Roux-en-Y reconstruction

Core tip: This study is a review of the status of diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using several endoscopic methods in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy, evaluating the results from multiple centers over the world. The descriptions of features of the respective endoscopes including the introduction of new endoscopes are summarized. Assessment of the procedures is concretely made by type of reconstruction methods and by type of applied endoscopes, which suggests the present and future challenges to be overcome.

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is now one of the most effective diagnostic and therapeutic modalities in patients with biliary diseases. The success rate is > 90% for patients with normal anatomy[1,2], however, ERCP in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy (SAGA) is far more challenging because of the inability of the endoscope to reach the blind end due to the long bowel passage, and of the complicated angulation. Some acute angled surgical limbs preclude the scope maneuverability and hinder the scope advancement.

The success of ERCP in patients with SAGA is affected by methods of surgical operations[3], and it often fails despite all the efforts. Consequently, many patients with SAGA are indicated for surgical or percutaneous operations, which is more invasive with greater risk of complications for patients than endoscopic therapy[4]. As an alternative procedure, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is widely accepted, though is technically limited in such cases as; the absence of the dilated intrahepatic ducts, a contraindication due to the abdominal dropsy or compromised coagulation. In addition, PTC cannot establish an access to the pancreatic duct system[4]. Then surgery is left as the only alternative[5], though it brings about greater adverse events, longer hospital admission, and increased financial costs. Thus, the endoscopic interventional approaches have come to be preferred.

Since Katon et al[6] introduced the first endoscopic approach to Billroth-II gastrectomy in 1975. In the late 1990s early 2000s, a number of papers studied on ERCP by using forward-viewing endoscopes or standard side-viewing duodenoscopes in various attempts, and the success rates widely ranged in 50%-92%[7-12]. As for Roux-en-Y reconstruction, Gostout et al[13] first reported the endoscopic approach in 1988. Since then, many attempts had been made by using duodenoscopes, pediatric colonoscopes, and oblique-viewing endoscopes, though the success rate was 33%-67% which was not satisfactory[12,14-16]. However, the advent of recently developed balloon assisted endoscopy (BAE) and spiral endoscopy (SE) radically gained the efficacy of endoscopic interventions in post-operative patients with not only Billroth-II gastrectomy but also with Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

SURGICALLY ALTERED ANATOMY

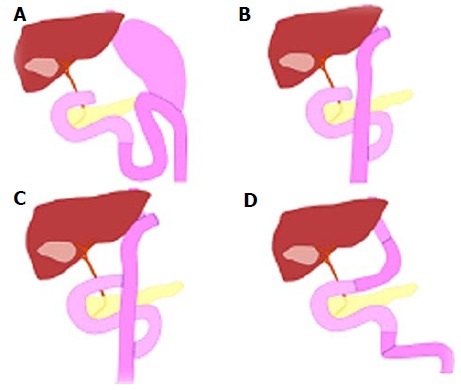

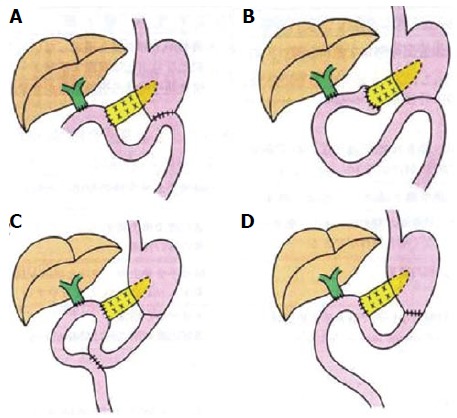

In Japan, pancreaticoduodenectomy for treatment of pancreatic carcinoma and a total or partial gastrectomy for treatment of gastric diseases are often encountered. There are four common types of surgical anatomic reconstruction from gastrectomy; Billroth-II reconstruction, Roux-en-Y reconstruction, double-tract reconstruction and jejunal pouch interposition (Figure 1). The number of Billroth-II reconstruction has decreased due to the effective treatment of peptic ulcer disease whereas that of Roux-en-Y reconstruction has increased due to the recent spread of laparoscopic surgery. There are three common types of surgical anatomic reconstruction from pancreaticoduodenectomy; the Whipple Method, the (modified) Child surgery, the Cattell Method, and the Imanaga Method (Figure 2). Currently in Japan, the modified Child surgery is the first line reconstruction method for pancreaticoduodenectomies.

Figure 1.

Schema of types of surgical anatomic reconstruction from gastrectomy. A: Billroth II reconstruction; B: Roux-en-Y reconstruction; C: Double-tract reconstruction; D: Jejunal pouch interposition.

Figure 2.

Schema of types of surgical anatomic reconstruction from pancreaticoduodenectomy. A: The Whipple Method; B: The (modified) Child surgery; C: The Cattell Method; D: The Imanaga Method.

In United States in contrast, Roux-enY gastric bypass (RYGB) for morbid obesity[17-20], hepaticojejunostomy for living donor liver transplantation (LDLT)[21,22] or treatment of biliary injury or disease[23,24], and pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampulla neoplasia and pancreatic carcinoma[25,26] are more frequently encountered types of surgically altered anatomies. Because the severe morbid obesity is rarely encountered in Japan, RYGB for obese is not common and neither is hepaticojejunostomy for LDLT.

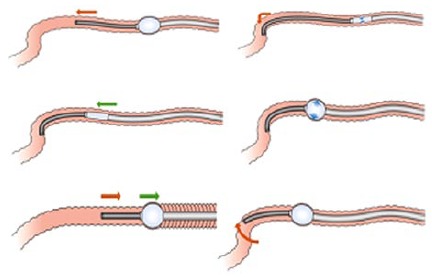

ENDOSCOPES

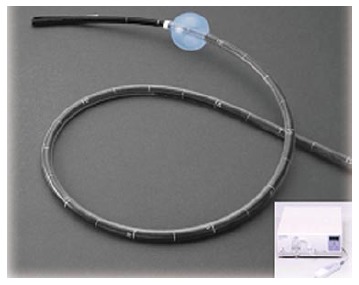

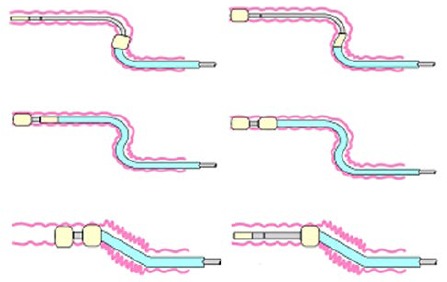

The invention of deep endoscopy has revolutionized the management of patients with mid-small-bowel diseases. Since the first introduction of double-balloon endoscopy (DBE) by Yamamoto[27] in 2001 (Figure 3), two additional techniques have become available, single-balloon endoscopy (SBE)[28,29] (Figure 4) and spiral endoscopy (SE)[30,31] (Figure 5). DBE and SBE entail a similar mechanism of advancement consisting of sequential bowel pleating by a push-pull technique that uses a balloon-fitted overtube with or without a second balloon inserted over the tip of a dedicated endoscope. The maneuver of the balloon or balloons in combination helps to hold and fix the intestine allowing the deep insertion by shortening the intestine. The inserting method of DBE (Figure 6) and SBE (Figure 7) is as shown in schemas. This technique enables the scope advancement selectively or retrogradely to reach the blind end in altered gastrointestinal anatomy with a high success rate. In contrast, SE is based on a different concept of insertion that pleats small bowel onto the endoscope to advance it through the lumen useing a rotating overtube [Discovery SB overtube (DSB); Spirus Medical, Inc., Stoughton, MA, United States]. This technique uses a spiral or raised helix-fitted overtube coupled with the endoscope, advanced as a unit into the small bowel by continuous rotation of the overtube in a manner similar to use of a corkscrew. An inner sleeve allows the independent motion of the overtube from the endoscope during advancement and withdrawal. The main difference between BAE and SE is that the latter uses a more or less continuous pleating of the small bowel by a clockwise rotation of the overtube rather than the push-pull technique. Unfortunately, SE is not currently commercially available.

Figure 3.

Double-balloon endoscopy. The short type double balloon enteroscope (EC- 530B; FUJIFILM, Osaka, Japan) with a working channel of 2.8 mm diameter and a working length of 152 cm.

Figure 4.

Single-balloon endoscopy. The standard type double balloon enteroscope (SIF- Q260; Olympus Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with a working channel of 2.8 mm diameter and a working length of 200 cm.

Figure 5.

Spiral endoscopy. Discovery SB overtube over the snteroscope.

Figure 6.

Schema of double-balloon endoscopy insertion.

Figure 7.

Schema of single-balloon endoscopy insertion.

Characteristic of DBE

There are two types of DBE. One is with a 2.2 mm working channel for observations, introduced in 2003. The DBE, EN-450P (FUJIFILM, Osaka, Japan) and the other is for treatments with a 2.8 mm working channel. For the treatment-type scope, it can be sorted into two types. The first type was introduced in 2004, the standard type DBE, EN-450T5 (FUJIFILM, Osaka, Japan) with a 2.8 mm working channel and a 200 cm working length. The second type is the short type DBE, EC-450BI5 (FUJIFILM, Osaka, Japan) with a 2.8 mm working channel and a 152 cm working length that was introduced in 2005 as a colonoscope, and subsequently in 2011 another short type DBE EI-530B (FUJIFILM, Osaka, Japan) was introduced with a 2.8 mm working channel and a 152 cm working length as a pancreatobiliary scope. The short type DBE with the 152 cm working length is preferred and used rather than the standard type DBE with the 200 cm working length to perform ERCP in patients with (SAGA), because the 152 cm working length of the short type DBE allows the availability of almost all the ERCP-related devices, whereas the 200 cm working length limits the use of those devices.

In 2013, the treatment-type scope (EN-580T; FUJIFILM, Osaka, Japan) with a 3.2 mm working channel was introduced after further improvement, though it remained as the standard type with a 200 cm working length. For the use in ERCP in patients with SAGA, further development of short type DBE is strongly expected.

Characteristic of SBE

In 2007, Olympus introduced the standard type SBE (SIF-Q260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with a 2.8 mm working channel and a 200 cm working length. Currently in Japan, only the standard type SBE is commercially available. Though, the short type SBE with a 3.2 mm working channel and a 152 cm working length (SIF-Y0004; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), has been newly developed as the first-generation prototype. Some papers have been already written about the use of this scope for ERCP reporting that the 3.2 mm-working channel of the short type SBE allowed a smooth pushing-in and pulling-out action of devices, facilitating the employment of devices including a covered metallic stent that had been not applicable with the 2.8 mm working channel, which consequently enabled almost all the treatments that were equivalent to those of the conventional ERCP[32-35]. Additionally, the short type SBE (SIF-Y0004; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) has been recently introduced as the second-generation prototype. This new endoscope is equipped with a passive bending part. This device helps the scope to pass and advance smoothly in the small intestine, which makes a special feature of this scope, as well as the 3.2 mm working channel that facilitated almost all the treatments equivalent to those of conventional ERCP. Some papers have been already written about ERCP using this scope[34,35], implying that deep insertion to the blind end using the second-generation prototype was easier than that using the first-generation prototype. With the equipment of this new device, the excelling performance in deep insertion to the blind end seems to be highly expected. Characteristics of BAE are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Information of balloon assisted endoscopy in Japan

|

FUJIFILM |

OLYMPUS |

|||||||

|

EN-450P/20 |

EN-450T5 |

EN-580T |

EC-450BI5 |

EI-530B |

SIF-Q260 |

SIF-Y 0004

(the first generation) |

SIF-Y 0004

(the second generation) |

|

| Standard type | Standard type | Standard type | Short type | Short type | Standard type | Short type | Short type | |

| Release date (yr) | 2003 | 2004 | 2013 | 2005 | 2011 | 2007 | Prototype | Prototype |

| Direction of view | Forward view | Forward view | Forward view | Forward view | Forward view | Forward view | Forward view | Forward view |

| Angle of view | 120° | 140° | 140° | 140° | 140° | 140° | 120° | 120° |

| Outer diameter (mm) | 8.5 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Total length (mm) | 2300 | 2300 | 2300 | 1820 | 1820 | 2305 | 1840 | 1840 |

| Working length (mm) | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 1520 | 1520 | 2000 | 1520 | 1520 |

| Working channel (mm) | 2.2 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Passive bending part | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

ENTERING THE AFFERENT LIMB BY TYPE OF SURGICAL RECONSTRUCTION

The method of insertion to the blind end differs according to the type of surgical reconstruction. A full comprehension of every feature of respective reconstruction method is essential.

Billroth II gastrectomy

In a case with Billroth II gastrectomy, there are short afferent loop (SAL) and long afferent loop (LAL). The latter contains a jejunojejunostomy called the Braun anastomosis between the afferent and the efferent limbs. As for SAL, the angulation of gastrojejunostomy is acute, and it is difficult to identify the intestinal orifice that is possibly-be-the afferent limb, as well as to insert. The afferent limbs often appear in the upper left direction over the normal anastomosis in the monitor with its lumen closed. Generally, identification of the afferent limb is challenging due to the complicated angulation of gastrojejunostomy, however once the scope is inserted, the blind end can be reached using conventional scopes such as duodenoscopes or forward-viewing endoscopes in a short time owing to the short length of afferent limb. Ciçek et al[36] reported that the success rate of reaching the blind end in patients with simple Billroth II gastroenterostomies using the duodenoscope was 83%.

In LAL, identification of the afferent limb is easy and the angulation is obtuse, which facilitates the scope insertion to the afferent limb because two intestinal orifices should be visible from the gastric lumen and either can be inserted easily. However due to the longer length of the afferent limb it requires a longer duration to reach the blind end. It also precludes the advancement to the blind end. Thus, deep insertion using the conventional scopes is quite difficult.

In patients with both a Billroth II gastroenterostomy and an additional Braun anastomosis, Ciçek et al[36] reported that the success rate was lowered to 29% for reaching the blind end. Whereas, Wu et al[37] reported the success rate of reaching the blind end in patients with both a Billroth II gastroenterostomy and an additional Braun anastomosis was 90% even by using duodenoscopes by inserting the middle entrance of the lumen. Lin et al[38] reported the success rate of reaching the blind end using a duodenoscope was 69%. Furthermore in all the unsuccessful cases DBE was employed for the reattempted session and could successfully access the blind end. Also, in our previous report using short type DBE, the success rate of reaching the blind end was 100%[39]. In cases with Braun anastomosis, we would also attempt the insertion to the middle entrance as Wu et al[37] reported. The Braun anastomosis shows like a maze. It is often considered as a disadvantage for endoscopic insertion, however when the efferent limb was entered by error, the scope can always return from the Braun anastomosis to the efferent limb. Applying the technique to insert the middle entrance, the Braun anastomosis is not necessarily a disadvantage for the scope insertion, rather can be an advantage.

Roux-en-Y reconstruction

In a case with Roux-en-Y reconstruction, identification of the afferent limb in Y anastomosis is very difficult. Also, the insertion is possibly hindered by the acute angulation of the afferent limb and the severe adhesion as a consequence of the long intestine to the blind end. In comparison with the cases of Billroth II gastrectomy, entering the afferent limb in cases with Roux-en-Y reconstruction is considered much more difficult. There are three challenges to be overcome for a successful insertion in cases with Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

The first challenge is identification of the afferent limb. It is difficult to identify the afferent limb in jejunojejunal anastomoses. Because of the maze-like feature of that area, endoscopists often lose their way or misjudge the orientation. Recently, Yano et al[40] reported a method using an intraluminal injection of indigo carmine to identify the afferent limb. The success rate was 80%, which suggests it should be helpful in identification of the afferent limb. However, the success rate based on our experience was approximately 50%. (unpublished observations) The divergence of the results could be reasoned that Yano et al[40] performed the procedure with the patient in a left-lateral position, whereas we performed in a pronation. Different postures in patients could have caused the divergence between the results.

The second challenge is the management of the complicated angulation in jejunojejunal anastomosis and the length of the afferent limb. It requires endoscopist’s experience and skill to control the of sharp angulation of jejunojejunal anastomosis in order to reach the afferent limb, which in some patients forms an angle of up to 180 degrees. Shah et al[41] reported the success rate of deep insertion could be raised by change of patient’s position from the typical semi-prone to a left-lateral or supine position during the procedure. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is a particularly challenging postsurgical anatomy in terms of the length of the afferent limb. It consists of the long limb (often > 100 cm) that is traversed from the gastrojejunal orifice to the jejunojejunal anastomosis to reach the afferent small-bowel limb[14]. This reconstruction method is frequently performed in the United States for morbid obesity. Therefore, it was reported laparoscope-assisted ERCP was more efficient than endoscope-assisted ERCP for RYGB[42,43]. The RYGB is infrequently performed in Japan. We assume that the primary disease and application of surgery method differ to some extent in gastrointestinal anatomy between the United States and Japan.

Adhesions are the third challenge, which are frequently observed in patients with SAGA. In Japan, lymphadenectomy of malignant tumors is likely to be performed, which often results in post-surgical severe adhesion. They often preclude the scope advancement, and if scope insertion to this lesion is forced by power, it increases a risk of perforation and bleeding. Therefore a careful maneuver and the discretion to withdraw are necessary for endoscopists.

In order to challenge these three obstacles, various attempts have been made and reported. Hintze et al[12] reported that the success rate of reaching the ampulla in Roux-en-Y anastomoses was 33%, compared with 92% in Billroth II anatomy. Wright et al[14] reported a use of colonoscopy to access the biliary orifice and a guide wire for a duodenoscope to attempt ERCP in 15 patients with long-limb Roux-en-Y anastomoses. Kikuyama et al[16] used the oblique-viewing endoscope in couple with an overtube and reported a high success rate, though it was based on the small case series. Generally the results were not sufficiently practical or satisfactory.

Recently, two multicenter studies have been reported on the use of overtube-assisted endoscopy in the United States. One multicenter study[41] observed 129 patients (180 procedures) focusing only on Roux-en-Y reconstruction, and reported that the success rate of reaching the papilla or the hepaticojejunostomy site was 71% using several scopes such as DBE, SBE and SE. They concluded there was no divergence in the result caused by the type of applied scopes, however, in the 3/4 of unsuccessful cases where endoscopy-ERCPs failed were simply due to the failure of reaching the blind end, which suggested that the success of endooscopy-ERCPs were significantly affected by the result of the deep insertion to the blind end. It indicates that insertion to the blind end is quite challenging and prerequisite for performing ERCP in cases with Roux-en-Y reconstruction. The other multicenter study[44] focused on ERCP in 79 patients using the short-type DBE for several anatomical variations. The success rate of reaching the blind end was 90% (based on success rates of 82% for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 95% for pancreatoduodenectomy, and 100% for Billroth II gastrectomy, hepaticojejunostomy, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, and Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy). They reported a very high success rate of 90% to reach the papilla or the hepaticojejunostomy site applying only the short type DBE. They raised two points as reasons for their good result owing to several advantages regarding the short DBE, which is quite agreeable: (1) DBE might have better maneuverability than the long conventional DBE, which is especially useful in patients with post-surgical severe adhesions; and (2) DBE allowed endoscopists to apply a power pressure more effectively to the endoscope, which might have raised the success rate of reaching the papilla or anastomosis.

REACHING THE BLIND END WITH OVERTUBE-ASSISTED ENDOSCOPY

Reaching the blind end with BAE

SBE and DBE are based on the same concept of insertion. The difference is the presence or absence of the balloon at the tip of the endoscope. The absence of a balloon fitted to the tip of the endoscope impairs the stability in case with severe adhesions around the blind end. The slippery feature of intestine prevents the tip of the endoscope from being fixed still and orienting into the required direction to follow the overtube, which eventually hinders the deep advancement of overtube. Tsujikawa et al[28] suggested that the DBE was advantageous in cases with sharp angulations of the small intestine, because the balloon on the tip of the DBE could help pass around such angulations better than the hook-shaped tip of the SBE. In comparison with DBE, it is assumed that SBE is more disadvantageous in a performance of deep insertion. Shah et al[41] reported the success rates of reaching the blind end in patients with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass using standard type SBE (n = 22) or DBE (n = 15), using both the standard and the short type DBE, was 73% in the SBE group and 87% in the DBE group. It suggested that DBE showed a better performance in deep insertion to the blind end. However, the new short type SBE with the passive bending part has been introduced in order to improve the success rate of insertion to the blind end. Obana et al[33] reported the success rate of insertion to the blind end using the short type SBE without the passive bending part was 73%, which was relatively low. Recently we have reported the success rate using the short type SBE with the passive bending part was 92%[34]. We assume that the success rate of deep insertion to the blind end might have been raised by the use of short type SBE equipped with the passive bending part. Today several challenges are yet to be overcome for deep insertions using BAEs into the blind end.

Reaching the blind end with SE

SE is based on the totally different concept of insertion from that of BAE. Previous small studies have suggested that SE allow more efficient advancement into the small bowel than BAE, however, there are not much paper written regarding the insertion to the blind end in patients with (SAGA) using SE. Therefore, sufficient data are not available to evaluate the SE in point of success rate of deep insertion, complication morbidity and efficacy. To evaluate the efficacy and the safety of this method, more studies and assessment in a larger number of cases are necessary.

OVERTUBE-ASSISTED ERCP

Many studies of DBE-assisted ERCP have been made since 2007[39,41,44-61]. And studies of SBE-assisted ERCP were subsequently introduced in 2009[62-69], followed by the studies of SE-assisted ERCP in 2011[70-72]. As the DBE was introduced prior to the development of the SBE and SE, there existed more number of reports of successful ERCP using DBE in patients with PD than that of the SBE and SE. In comparison of the results before and after the advent of BAE and/or SE, it is obvious that the success rate has radically improved to a satisfactory level.

DBE-assisted ERCP

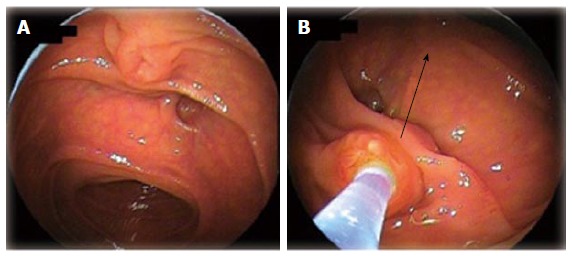

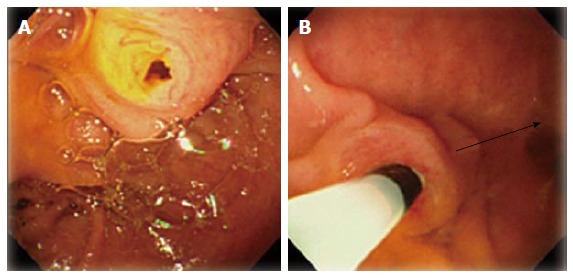

There are a lot of studies on DBE-assisted ERCP with wide ranging results. The success rate of ERCP-related interventions varied 60%-100%[39,41,44-61], which was probably because many studies were based on a small number of cases. We have reported a large case single center study[39], as a single center study in which we evaluated 103 procedures DBE-assisted ERCP by type of reconstruction method in 68 patients. The overall success rate for ERCP was 95% (based on success rates for Roux-en-Y reconstruction, Billroth II reconstruction, and pancreatoduodenectomy of 91%, 100%, and 100%, respectively). In all successful ERCP cases, endoscopic therapeutic interventions were successfully accomplished. One multicenter study[41] reported the overall ERCP success rate was 63%. The success rate of ERCP using SBE and DBE was similar between Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and other long-limb surgical bypass. It also reported that the success rate of ERCP in cases where the blind end was successfully reached was 88%, which was satisfactory though they explained the success rate was lowered because many cases had contained papilla. Itoi et al[63] reported the success rate of ERCP using the standard type SBE was 72.3% mentioning that the biliary approach in patients with naïve papilla was difficult[63]. It is agreeable, however, in our previous study[39], the success rate of cannulation into papilla was 97%, suggesting the different type of applied scopes could affect the divergence of the results. For instance, because the position of the working channel of DBE is located at 6:30, an attempt to bring the papilla in a 6 o’clock direction in monitor will allow a down-angled maneuver that helps to fix the papilla still by a direct power pressure, which facilitates a stable cannulation (Figure 8). Whereas, the position of the working channel of SBE is located at 9 o’clock, which makes difficult to fix the papilla, precluding a stable cannulation as a consequence (Figure 9). Whereas Shah et al[41] concluded the type of scopes did not affect their result, though they used mostly the standard type DBE and SBE with the 200 cm working length in many cases. Namely, it could be inferred that not only using the DBE but the short type was the best appropriate scope for cannulation in cases with papilla. Siddiqui et al[44] reported the overall ERCP success rate using only the short-type DBE was 90% raising a reason for the excellent result as; the short DBE allowed the use of commercially available ERCP cannulas for performance of wire-guided cannulation, and therapeutic instruments could be applied to carry out successful therapeutic treatments.

Figure 8.

Biliary cannulation using double-balloon endoscopy in a patient with papilla. A: Papilla when the blind end was accessed; B: Locating papilla in 6 o’clock direction in the monitor, and performing cannulation adjusting the axis of catheter into 12 o’clock direction along the biliary duct.

Figure 9.

Biliary cannulation using single-balloon endoscopy in a patient with papilla. A: Papilla when the blind end was accessed; B: Locating papilla in 8-9 o’clock direction in the monitor, and performing cannulation adjusting the axis of catheter into 3 o’clock direction along the biliary duct.

SBE-assisted ERCP

Dellon et al[64] evaluated a use of the standard type SBE for diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP. They observed 4 patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy in total. (1 patient with RYGB, 2 patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy caused by bile duct injury, and 1 patient with Roux-en-Y anatomy after liver transplantation). The overall success rate of the therapeutic ERCP on the first session was 50%. In this report, the standard type SBE with 200 cm working length that was only applicable to limited variety of devices was used for the therapeutic ERCP, which could have caused the unsatisfactory success rate of SBE-assisted ERCP.

However, along the recent development of the short type SBE, several reports have been made on the short type SBE-assisted ERCP. The overall success rate of ERCP was 78%-90%, which was higher than that of ERCP using the standard type SBE. It could be reasoned that the 152 cm working length allowed the use of more variety of available devices.

SE-assisted ERCP

Although only published in abstract form, some studies on SE-assisted ERCP have been made. In a multi-center study, Shah et al[41] reported 129 patients with surgically altered anatomy who underwent ERCP using SBE (n = 15), DBE (n = 22), and SE (n = 13). The ERCP success rates of each method were 60%, 63%, and 65%, respectively. Lennon et al[70] discussed the comparison of SE and SBE. They concluded there was no significant difference between SE and SBE, and their overall ERCP success rate was 44%.

A review of studies evaluating overtube assisted ERCP in patients with (SAGA) via various techniques is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Review studys evaluating endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using several enteroscopy in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy

| Ref. | No. of cases | Type of scope | Enteroscopy success (%) | Success rate of ERCP | Overall ERCP success (%) |

| Mehdizadeh et al[48] | 5 | Standard type DBE | 67 | 100 | 67 |

| Mönkemüller et al[53] | 18 | Standard type DBE | 94 | 85 | 83 |

| Maaser et al[4] | 11 | Standard type DBE | 100 | 64 | 64 |

| Kuga et al[59] | 6 | Standard type DBE | 100 | 83 | 83 |

| Tsujino et al[49] | 12 | Short type DBE | 100 | 94 | 94 |

| Siddiqui et al[44] | 79 | Short type DBE | 89 | 90 | 81 |

| Shimatani et al[39] | 103 | Short type DBE | 97 | 96 | 94 |

| Tomizawa et al[69] | 22 | Standard type SBE | 68 | 73 | 50 |

| Itoi et al[63] | 13 | Standard type SBE | 92 | 83 | 77 |

| Dellon et al[64] | 4 | Standard type SBE | 75 | 67 | 50 |

| Yamauchi et al[32] | 31 | Short type SBE | 90 | 89 | 81 |

| Obana et al[33] | 19 | Short type SBE | 79 | 66 | 53 |

| Shimatani et al[34] | 26 | Short type SBE | 92 | 92 | 85 |

| Lennon et al[70] | 29 | Standard type SBE | 55 | 87 | 48 |

| Shah et al[41] | 27 | Standard type DBE | 85 | 85 | 63 |

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; DBE: Double balloon endoscopy; SBE: Single-balloon endoscopy.

COMPLICATIONS

It is assumed that the morbidity of complications is affected by type of applied endoscopes and by method of surgical reconstruction. The common complications for overtube-assisted ERCP are comparable with those of conventional ERCP such as bleeding, perforation, and post-ERCP pancreatitis. There are few studies made only in a small case series, however, the actual rates of perforation, bleeding, and pancreatitis associated with overtuve-assisted ERCP is unknown.

Performing ERCP in Patients with SAGAposes a greater risk of complications than in patients with NGA[73,74]. The risk of retroperitoneal perforation in patients with Billroth II surgery has been reported as high as 7%-10%[74]. Regarding Roux-en-Y reconstruction, our previous study retrospectively observed 55 procedures, reporting that procedural complications developed in 5 of 55 procedures (9%)[39]. Shah et al[41] retrospectively observed 129 patients, reporting that procedural complications were observed in 16 of 129 patients (12%), including pancreatitis (mild = 4, severe = 1), mild bleeding (n = 1), abdominal pain requiring hospital admission (n = 3), and throat pain requiring physician contact (n = 4). Two perforations were also observed and 1 case of death occurred. However, apart from those, studies based on only small case series can be found[75,76]. In order to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the procedure, it is necessary to analyze and evaluate data of complications out of large case studies from multiple centers prospectively, particularly for Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

CONCLUSION

The endoscopic approach to PD in patients with (SAGA) has radically become practical. Development of new modalities such as DBE, SBE, and SE is in progress as a consequence of an increased demand for the endoscopic interventions. For the safety and a higher success of the procedures, further development of the scopes and devices, standardization of technical maneuverability, establishment of guidelines in decision making of indicated and contraindicated cases, and assessment of complications from a larger multi-center study are necessary.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 16, 2014

First decision: July 29, 2014

Article in press: March 9, 2015

P- Reviewer: Li YM, Tekin A, Wehrmann T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Suissa A, Yassin K, Lavy A, Lachter J, Chermech I, Karban A, Tamir A, Eliakim R. Outcome and early complications of ERCP: a prospective single center study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112–125. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbes A, Cotton PB. ERCP and sphincterotomy after Billroth II gastrectomy. Gut. 1984;25:971–974. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.9.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maaser C, Lenze F, Bokemeyer M, Ullerich H, Domagk D, Bruewer M, Luegering A, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. Double balloon enteroscopy: a useful tool for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in the pancreaticobiliary system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teplick SK, Flick P, Brandon JC. Transhepatic cholangiography in patients with suspected biliary disease and nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:193–197. doi: 10.1007/BF01887344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katon RM, Bilbao MK, Parent JA, Smith FW. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with gastrectomy and gastrojejunostomy (Billroth II), A case for the forward look. Gastrointest Endosc. 1975;21:164–165. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(75)73838-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MH, Lee SK, Lee MH, Myung SJ, Yoo BM, Seo DW, Min YI. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and needle-knife sphincterotomy in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy: a comparative study of the forward-viewing endoscope and the side-viewing duodenoscope. Endoscopy. 1997;29:82–85. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aabakken L, Holthe B, Sandstad O, Rosseland A, Osnes M. Endoscopic pancreaticobiliary procedures in patients with a Billroth II resection: a 10-year follow-up study. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergman JJ, van Berkel AM, Bruno MJ, Fockens P, Rauws EA, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. A randomized trial of endoscopic balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile duct stones in patients with a prior Billroth II gastrectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:19–26. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.110454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin LF, Siauw CP, Ho KS, Tung JC. ERCP in post-Billroth II gastrectomy patients: emphasis on technique. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:144–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osnes M, Rosseland AR, Aabakken L. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and endoscopic papillotomy in patients with a previous Billroth-II resection. Gut. 1986;27:1193–1198. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.10.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hintze RE, Adler A, Veltzke W, Abou-Rebyeh H. Endoscopic access to the papilla of Vater for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with billroth II or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:69–73. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gostout CJ, Bender CE. Cholangiopancreatography, sphincterotomy, and common duct stone removal via Roux-en-Y limb enteroscopy. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:156–163. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright BE, Cass OW, Freeman ML. ERCP in patients with long-limb Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy and intact papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:225–232. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chahal P, Baron TH, Topazian MD, Petersen BT, Levy MJ, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in post-Whipple patients. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1241–1245. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuyama M, Sasada Y, Matsuhashi T, Ota Y, Nakahodo J. ERCP afterRoux-en-Y reconstruction can be carried out using an oblique-viewing endoscope with an overtube. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:180–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsk R, Freedman J, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F, Näslund E. Antiobesity surgery in Sweden from 1980 to 2005: a population-based study with a focus on mortality. Ann Surg. 2008;248:777–781. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318189b0cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flum DR, Salem L, Elrod JA, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1903–1908. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livingston EH. Procedure incidence and in-hospital complication rates of bariatric surgery in the United States. Am J Surg. 2004;188:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Fletcher DR. Incidence of bariatric surgery and postoperative outcomes: a population-based analysis in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;189:198–202. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soejima Y, Taketomi A, Yoshizumi T, Uchiyama H, Harada N, Ijichi H, Yonemura Y, Ikeda T, Shimada M, Maehara Y. Biliary strictures in living donor liver transplantation: incidence, management, and technical evolution. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:979–986. doi: 10.1002/lt.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi NJ, Suh KS, Cho JY, Kwon CH, Lee KU. In adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation hepaticojejunostomy shows a better long-term outcome than duct-to-duct anastomosis. Transpl Int. 2005;18:1240–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Tielve M, Hinojosa CA. Acute bile duct injury. The need for a high repair. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1351–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8705-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson SR, Koehler A, Pennington LK, Hanto DW. Long-term results of surgical repair of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2000;128:668–677. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, Ord SE, Sauter PK, Coleman J, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg. 1997;226:248–257; discussion 257-260. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meguid RA, Ahuja N, Chang DC What constitutes a “high-volume” hospital for pancreatic resection J Am Coll Surg 2008; 206: 622.e1-622.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216–220. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsujikawa T, Saitoh Y, Andoh A, Imaeda H, Hata K, Minematsu H, Senoh K, Hayafuji K, Ogawa A, Nakahara T, et al. Novel single-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of the small intestine: preliminary experiences. Endoscopy. 2008;40:11–15. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartmann D, Eickhoff A, Tamm R, Riemann JF. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy using a single-balloon technique. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E276. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akerman PA, Cantero D. Spiral enteroscopy and push enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:357–369. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akerman PA, Agrawal D, Cantero D, Pangtay J. Spiral enteroscopy with the new DSB overtube: a novel technique for deep peroral small-bowel intubation. Endoscopy. 2008;40:974–978. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamauchi H, Kida M, Okuwaki K, Miyazawa S, Iwai T, Takezawa M, Kikuchi H, Watanabe M, Imaizumi H, Koizumi W. Short-type single balloon enteroscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1728–1735. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obana T, Fujita N, Ito K, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Hashimoto S, et al. Therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography using a single-balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:601–607. doi: 10.1111/den.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Ikeura T, Mitsuyama T, Okazaki K. Evaluation of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using a newly developed short-type single-balloon endoscope in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:147–155. doi: 10.1111/den.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwai T, Kida M, Yamauchi H, Imaizumi H, Koizumi W. Short-type and conventional single-balloon enteroscopes for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with surgically altered anatomy: single-center experience. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:156–163. doi: 10.1111/den.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciçek B, Parlak E, Dişibeyaz S, Koksal AS, Sahin B. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Billroth II gastroenterostomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1210–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu WG, Gu J, Zhang WJ, Zhao MN, Zhuang M, Tao YJ, Liu YB, Wang XF. ERCP for patients who have undergone Billroth II gastroenterostomy and Braun anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:607–610. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin CH, Tang JH, Cheng CL, Tsou YK, Cheng HT, Lee MH, Sung KF, Lee CS, Liu NJ. Double balloon endoscopy increases the ERCP success rate in patients with a history of Billroth II gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4594–4598. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimatani M, Matsushita M, Takaoka M, Koyabu M, Ikeura T, Kato K, Fukui T, Uchida K, Okazaki K. Effective “short” double-balloon enteroscope for diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy: a large case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:849–854. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yano T, Hatanaka H, Yamamoto H, Nakazawa K, Nishimura N, Wada S, Tamada K, Sugano K. Intraluminal injection of indigo carmine facilitates identification of the afferent limb during double-balloon ERCP. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E340–E341. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah RJ, Smolkin M, Yen R, Ross A, Kozarek RA, Howell DA, Bakis G, Jonnalagadda SS, Al-Lehibi AA, Hardy A, et al. A multicenter, U.S. experience of single-balloon, double-balloon, and rotational overtube-assisted enteroscopy ERCP in patients with surgically altered pancreaticobiliary anatomy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross AS. Techniques for Performing ERCP in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2012;8:390–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleem A, Levy MJ, Petersen BT, Que FG, Baron TH. Laparoscopic assisted ERCP in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1760-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddiqui AA, Chaaya A, Shelton C, Marmion J, Kowalski TE, Loren DE, Heller SJ, Haluszka O, Adler DG, Tokar JL. Utility of the short double-balloon enteroscope to perform pancreaticobiliary interventions in patients with surgically altered anatomy in a US multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:858–864. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2385-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimatani M, Matsushita M, Takaoka M, Kusuda T, Fukata N, Koyabu M, Uchida K, Okazaki K. “Short” double balloon enteroscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with conventional sphincterotomy and metallic stent placement after Billroth II gastrectomy. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E19–E20. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albrecht H, Konturek PC, Diebel H, Kraus F, Hahn EG, Raithel M. Successful interventional treatment of postoperative bile duct leakage after Billroth II resection by unusual procedure using double balloon enteroscopy. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:CS29–CS33. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haruta H, Yamamoto H, Mizuta K, Kita Y, Uno T, Egami S, Hishikawa S, Sugano K, Kawarasaki H. A case of successful enteroscopic balloon dilation for late anastomotic stricture of choledochojejunostomy after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1608–1610. doi: 10.1002/lt.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mehdizadeh S, Ross A, Gerson L, Leighton J, Chen A, Schembre D, Chen G, Semrad C, Kamal A, Harrison EM, et al. What is the learning curve associated with double-balloon enteroscopy Technical details and early experience in 6 U.S. tertiary care centers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsujino T, Yamada A, Isayama H, Kogure H, Sasahira N, Hirano K, Tada M, Kawabe T, Omata M. Experiences of biliary interventions using short double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis or hepaticojejunostomy. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haber GB. Double balloon endoscopy for pancreatic and biliary access in altered anatomy (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:S47–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emmett DS, Mallat DB. Double-balloon ERCP in patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y surgery: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1038–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aabakken L, Bretthauer M, Line PD. Double-balloon enteroscopy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1068–1071. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mönkemüller K, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. Therapeutic ERCP with the double-balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:992–996. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chu YC, Yang CC, Yeh YH, Chen CH, Yueh SK. Double-balloon enteroscopy application in biliary tract disease-its therapeutic and diagnostic functions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koornstra JJ, Fry L, Mönkemüller K. ERCP with the balloon-assisted enteroscopy technique: a systematic review. Dig Dis. 2008;26:324–329. doi: 10.1159/000177017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsushita M, Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Okazaki K. “Short” double-balloon enteroscope for diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3218–3219. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02161_18.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsushita M, Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Okazaki K. Effective endoscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis: a single-, double-, or “short” double-balloon enteroscope. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:874–885; author reply 875. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1110-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsushita M, Shimatani M, Ikeura T, Takaoka M, Okazaki K. “Short” double-balloon or single-balloon enteroscope for ERCP in patients with billroth II gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2294; author reply 2294–2295. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuga R, Furuya CK, Hondo FY, Ide E, Ishioka S, Sakai P. ERCP using double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy. Dig Dis. 2008;26:330–335. doi: 10.1159/000177018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Matsushita M, Okazaki K. Endoscopic approaches for pancreatobiliary diseases in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 1:70–78. doi: 10.1111/den.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Okazaki K. Tips for double balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y reconstruction and modified child surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:E22–E28. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawamura T, Yasuda K, Tanaka K, Uno K, Ueda M, Sanada K, Nakajima M. Clinical evaluation of a newly developed single-balloon enteroscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1112–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Umeda J, Moriyasu F. Single-balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y anastomosis (with video) Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:93–99. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dellon ES, Kohn GP, Morgan DR, Grimm IS. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with single-balloon enteroscopy is feasible in patients with a prior Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1798–1803. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0538-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. ERCP using single-balloon instead of double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E19–E20. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neumann H, Fry LC, Meyer F, Malfertheiner P, Monkemuller K. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using the single balloon enteroscope technique in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Digestion. 2009;80:52–57. doi: 10.1159/000216351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moreels TG, Pelckmans PA. Comparison between double-balloon and single-balloon enteroscopy in therapeutic ERC after Roux-en-Y entero-enteric anastomosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:314–317. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i9.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang AY, Sauer BG, Behm BW, Ramanath M, Cox DG, Ellen KL, Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Single-balloon enteroscopy effectively enables diagnostic and therapeutic retrograde cholangiography in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tomizawa Y, Sullivan CT, Gelrud A. Single balloon enteroscopy (SBE) assisted therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in patients with roux-en-y anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:465–470. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2916-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lennon AM, Kapoor S, Khashab M, Corless E, Amateau S, Dunbar K, Chandrasekhara V, Singh V, Okolo PI. Spiral assisted ERCP is equivalent to single balloon assisted ERCP in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1391–1398. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-2000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kogure H, Watabe H, Yamada A, Isayama H, Yamaji Y, Itoi T, Koike K. Spiral enteroscopy for therapeutic ERCP in patients with surgically altered anatomy: actual technique and review of the literature. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:375–379. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wagh MS, Draganov PV. Prospective evaluation of spiral overtube-assisted ERCP in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:439–443. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.04.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bagci S, Tuzun A, Ates Y, Gulsen M, Uygun A, Yesilova Z, Karaeren N, Dagalp K. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Billroth II anastomosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;52:356–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Faylona JM, Qadir A, Chan AC, Lau JY, Chung SC. Small-bowel perforations related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:546–549. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. ERCP with the double balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1961–1967. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Fukuzawa K, Moriyasu F, et al. Long- and short-type double-balloon enteroscopy-assisted therapeutic ERCP for intact papilla in patients with a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:713–721. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1226-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]