Abstract

Background:

Clinical guidelines are important instruments for increasing the quality of clinical practice in the treatment team. Compilation of clinical guidelines is important due to special condition of the neonates and the nurses facing critical conditions in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). With 98% of neonatal deaths occurring in NICUs in the hospitals, it is important to pay attention to this issue. This study aimed at compilation of the neonatal palliative care clinical guidelines in NICU.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted with multistage comparative strategies with localization in Isfahan in 2013. In the first step, the components of the neonatal palliative care clinical guidelines were determined by searching in different databases. In the second stage, the level of expert group's consensus with each component of neonatal palliative care in the nominal group and focus group was investigated, and the clinical guideline was written based on that. In the third stage, the quality and applicability were determined with the positive viewpoints of medical experts, nurses, and members of the science board of five cities in Iran. Data were analyzed by descriptive statistics through SPSS.

Results:

In the first stage, the draft of neonatal palliative care was designed based on neonates’, their parents’, and the related staff's requirements. In the second stage, its rank and applicability were determined and after analyzing the responses, with agreement of the focus group, the clinical guideline was written. In the third stage, the means of indication scores obtained were 75%, 69%, 72%, 72%, and 68% by Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument.

Conclusions:

The compilation of the guideline can play an effective role in provision of neonatal care in nursing.

Keywords: Clinical guideline, end-of-life care, neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal palliative care

INTRODUCTION

Patients’ care has become surprisingly sophisticated in the past decades and clinical decision-making is different and difficult, based on patients’ benefits and organizational benefits.[1] Loorieyoos writes that the structure of giving care is rapidly changing and clinical guidelines and standards are one of the important tools to increase the quality of care.[2] Application of a clinical guideline, positively affecting the quality promotion and care administration, is a controversial issue.[2] Guidelines have a special position in provision of solutions and standardizing the methods, and act as a guiding tool for the treatment team.[3] The reasons for application of such guidelines in health and treatment centers is to promote the quality of care, lower the costs, enhance public health level, and synchronize the national standards with the international ones.[4] In 1990, the Washington Medical Association announced that clinical guidelines systemically improve clinical care and patients’ care decision-making in specific conditions.[5] In 1996, Saket et al. designed a clinical guideline based on the best existing evidences.[6] Nurses working in ICU need valid protocols and guidelines in provision of high-quality care to give appropriate and ideal services to the patients who are predisposed to different risks. In the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), patients’ need for such protocols and guidelines is highlighted due to special conditions of the neonates and the critical conditions that the nurses face.[7] A clinical practice guideline is a collection of systematic recommendations which help both the health care providers and receivers in decision-making in special conditions.[8] Such conditions exist in NICUs where despite the best quality of care, the mortality rate is over 10%,[9] and 98% of neonatal deaths are reported here. Therefore, the need for palliative care in such conditions has been emphasized.[10] Palliative care is active and holistic care given to untreatable patients who are at the end stage. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the primary goal of palliative care is provision of quality of life for the neonates who are in critical conditions or those who have a short life.[11,12] This sort of care promote family-centered care.[13] Neonatal palliative care focuses on the neonates and families, and aims at prevention of neonates’ sufferings and improvement of their life and quality of their deaths.[14]

The importance of palliative care has been clarified in the past decades and its various outcomes have been shown. Especially, in the past two decades, adults’ palliative care has been in demand all over the world. Meanwhile, the background for neonatal palliative care for end-stage neonates had not been seriously considered.[15] In recent years, neonatal palliative care has increasingly entered the neonatal nursing care culture.[16] Most of the NICUs enjoy strategies for near-death care, but few have palliative care guidelines. Nurses do not receive adequate education to support the families in their mournful ceremonies, as the nursing programs lack such educational programs in this field. These problems and shortages in relation with education and palliative care result in neonates and their parents not receiving the care they deserve.[17] Palliative care is not often started immediately after a life-threatening disease is diagnosed, and may be provided just in the last 2 days, and is not in the form of a practical program but a brief process based on the health care providers’ attitude. Meanwhile, it should be constantly provided in the NICU.[18] The present study aimed to design a clinical guideline for neonatal palliative care in Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a comparative multi-stage study conducted to provide and design a neonatal palliative care clinical guideline with localization approach. Therefore, the researcher, through review of palliative care guidelines in other countries and inquiring the domestic researchers’ indications, adopted comparative research methodology to design neonatal palliative care clinical guideline to suggest a program fitting the Iranian culture. In order to find the arrangement of neonatal palliative care clinical guideline in the form of a model, the existing guidelines in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) website as well as in other websites related to the subject of the study were used.[6] This study included three stages which are described below.

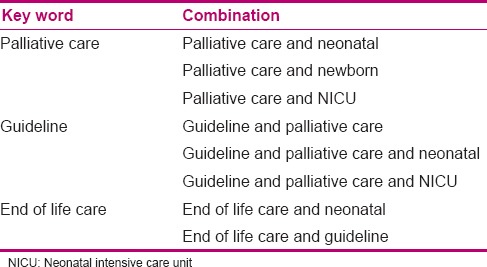

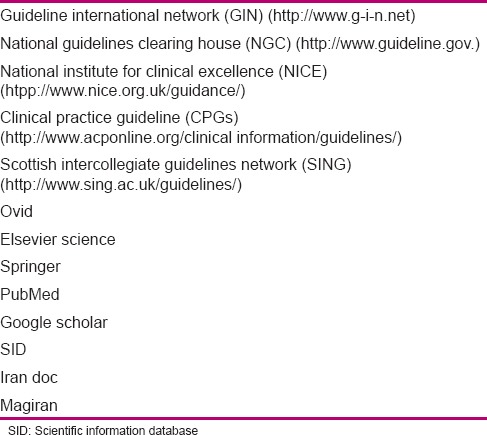

The first stage aimed to determine the components of neonatal palliative care through searching various databases, obtaining the resources, literature review, and combining them with each other, and then, designing the primary draft of recommendations. At this stage, a literature review was conducted through library and electronic search. In order to obtain a clinical guideline and access the international articles on neonatal palliative care, a search was conducted with the help of related key words [Table 1] in international databases [Table 2]. Then, literature review was conducted, and the articles were compared concerning the primary outcomes. Next, the components of neonatal palliative care clinical guidelines were defined and categorized based on conditions and position of the target population, and finally, the draft of recommendations was designed in the form of a questionnaire for a survey. Modification and revision of the recommendations were conducted based on experts’ viewpoints.

Table 1.

Combination of key words used in systematic research

Table 2.

Research database

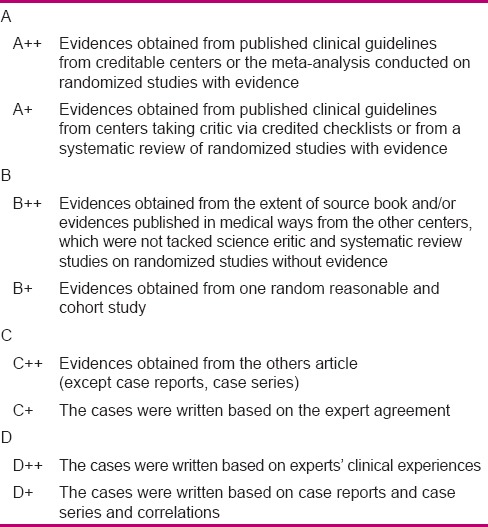

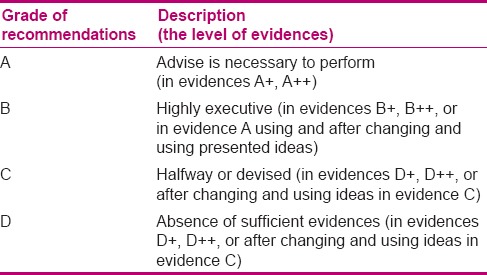

Stage two aimed to determine the expert panel's consensus level with each component of neonatal palliative clinical care guideline through conducting a survey in a nominal group, determination of recommendations by GRADE approach, defining the discussable and revisable recommendations, formation of a focus group, and analysis of revised recommendations and their finalization. At this stage, a collection of the viewpoints in the form of a questionnaire was given to 20 experts based on purposive sampling. Selection of focus group members was based on their common experience in the subject of study. At this stage, scientific validity, applicability, ranking, strengths, and weak points of the clinical guideline were surveyed. Ranking referred to the necessity of existence for each recommendation and its effect on promotion of quality of care, and applicability referred to the possibility of performance and measurement of care in Iran. The expert panel's consensus with each component of neonatal palliative clinical care guideline was determined; the collected viewpoints were analyzed and the grade of each recommendation was identified, as given in Tables 3 and 4, through consultation with experts. The items and recommendations that had a lower grade, applicability, and rank,[19,20] and needed revision and modification were allocated. Then, in the focus group session, the allocated recommendations were discussed and finalized, and the indications were considered and the final national clinical guideline was written.

Table 3.

The evaluation of the evidences’ level

Table 4.

Grades of recommendations

The goal of the third stage was defining the quality and appropriateness of the clinical guideline from the viewpoint of medical professionals, academic members, and pediatric department of the nursing school, and the nurses working in NICUs. It was performed by sending the clinical guideline and the Clinical Guideline Evaluation questionnaire to the above-mentioned subjects selected through census sampling and then collecting their indications in relation to appropriateness and quality of suggested guideline with regard to educational, executive, cultural, and social conditions in Iran, as well as its applicability.[21] Then, the results were analyzed by descriptive statistical methods (frequency distribution, mean) through a statistical software. Scientific and Ethical considerations of his study has been approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

RESULTS

Findings of the first stage

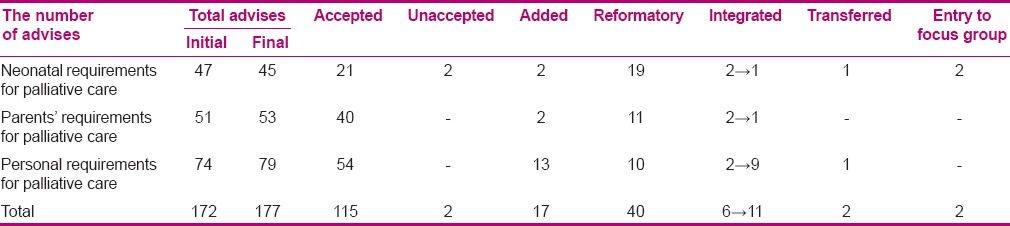

At this stage, the components of neonatal palliative clinical care guideline were determined. Therefore, in order to detect various domains of neonatal palliative care as well as clinical guidelines in this context, the researcher decided to detect and extract the needed databases and websites. After searching, 6014 articles and clinical guidelines were found, which were reviewed based on fellow chart 1, and 50 articles and clinical guidelines were selected to design neonatal palliative clinical care guideline. After searching and collecting the data, neonatal palliative clinical care guideline components were extracted. Then, the extracted materials from all selected resources were compared and combined. Then, the data were analyzed through content analysis and with the help of experts, and similar items were deleted and the overlapping items were combined. The recommendations were categorized, revised, and compared for several times. Finally, the materials were categorized into three general domains. There were 45 items for neonates’ needs in palliative care, 53 items in relation to parents’ needs in neonatal palliative care, and 79 items in the context of staff's needs in neonatal palliative care. The results of the questionnaire analysis in the first stage have been presented in Table 5. At the end of this stage, items were designed in the form of a questionnaire to survey the experts’ viewpoints.

Table 5.

The results of analyzing the questionnaire at the first stage

Findings of the second stage

The panel of experts’ level of consensus with neonatal palliative care, ranking, and applicability of care were determined using the questionnaire designed in the previous stage and the grade of recommendations was clarified. The indications and modifications done in the list of care resulted in preparation and design of neonatal palliative clinical care guideline based on the rank, applicability, and balance of recommendations and discussion about them in the focus group. The care with rank and applicability of 1–2 and evidence levels of A and B was precisely considered, except that it needed a revision. The care with rank and applicability of 3–4 and evidence levels of C and D was discussed and revised in the focus group. Out of 24 recommended items discussed in the focus group, 19 were accepted, 4 were deleted, and 2 items needed separate focus- groups related expert revision. Suggestions and performed modifications in care resulted in the final clinical guidelines, based on items rank, applicability, and the level of evidence, and discussion about them in the focus group. It included the following domains:

Neonates’ needs in neonatal palliative care including nutrition, end-of-life care concerning neonates’ peace, and comfort and pain relief

Parents’ needs in neonatal palliative care including end-of-life family-centered decision-making, appropriate environment, making communication with the parents, and their support

Staff's needs to administer neonatal palliative care including ethical and legal considerations, breaking bad news, making a care plan, and staff's educational needs.

Findings of the third stage

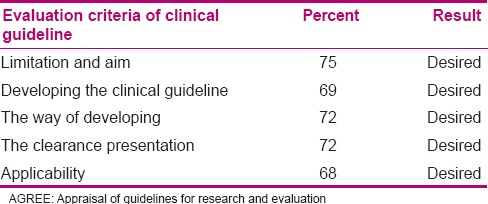

At the third stage, appropriateness and quality of clinical guideline was evaluated by NICU nurses and experts in Isfahan, Tehran, Mashhad, and Tabriz through Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) questionnaire, and the results were analyzed by descriptive statistical tests through SPSS 20. Finally, neonatal palliative clinical care guideline was finalized after modification and revision. Most of the participants (67.6%) had a bachelor's degree. Their mean age was 34 years, and their mean work experience was 9.7 years. Ninety-one percent of the respondents were female and 6.2% were male; 68.3% were married and 22.8% were single. The results of the quality of clinical guideline evaluation have been presented in Table 6. In the final evaluation, 51.7% of the respondents recommended this guideline, 42.1% recommended its use based on condition of changes, and 1.4% did not recommend it. Total mean score of clinical guideline was 80 from 100.

Table 6.

Evaluation of the quality of the clinical guideline according to AGREE questionnaire

DISCUSSION

Protocol of end-of-life neonatal palliative care, designed by Catlin and Carter, is a modern model for neonatal palliative care, which has appropriate number, combination, and variation of care, and is counted as the richest model. This protocol has been adopted in all articles and neonatal palliative clinical guidelines. Due to its good ability, this model was used as the primary core of the guideline designed in the present study. In designing the above-mentioned protocol, Delphi technique was used, while in the present study, a nominal group and a focus group were adopted to reach experts’ consensus.[22] Australian neonatal palliative clinical care guideline is one of the guidelines adopted in the present study, which is very comprehensive and covers a vast domain of neonatal palliative care. The major difference between the above clinical guideline and the one used in our study is that it contains the sections of introduction (domain, goal, and definition), background, different aspects of neonatal palliative care, and home care. We also completed the guideline in other fields based on already published guidelines in valid centers and explained the philosophy, mission, goal (general goals, specific goals, and expected results), domain (type of clinical guideline, target population, and clinical guideline nurses), definition and importance of the subject, and guideline development method, all in the section of introduction. Background section was replaced by general points which included ethical and legal considerations of neonatal palliative care, based on national regulations and religious and general principles of neonatal palliative care. The third section is associated with the components of neonatal palliative care. The section of home care in the above guideline was not used, as it did not address our target population.[23] In the present study, extraction and collection of care were conducted by revision of related articles and clinical guidelines, and the components of neonatal palliative care were defined to design clinical guidelines. Several studies are in line with the process of our research, including Toman et al., who designed clinical guideline of an educational program in CHF (Cogestive Heart Failure) patients and their families. They firstly reviewed the related literature about CHF patients, and then extracted educational programs from them. Next, they investigated the association between education and clinical evidences and, finally, performed that.[24]

We handed the primary draft of clinical guideline to the nominal group based on localization approach, and surveyed the rank and applicability of care. Sadeq Tabrizi and Gharibi suggested a national accreditation model via Delphi technique in their article in which both standards of rank and applicability had been surveyed, which is consistent with the present study. Meanwhile, in their study, a nine-point scale was adopted for scoring the recommendations, instead of a four-point scale used in our study. They also used acceptance, deletion, and combination or modification of the standards in their Delphi technique. We also used deletion, acceptance, and combination of the recommendations in designing our clinical guideline.[25]

Rolley et al. designed nursing guidelines for the patients undergoing invasive cardiac interventions. Their strategy included a vast literature review about the patients undergoing cardiac invasive interventions. At this stage, literature review was conducted by an evidence-based process, in which lesser number of studies was a limitation. In the next stage, a panel of experts was formed, and then, modification of care was conducted based on Delphi technique. Meanwhile, we used a nominal group and formed a focus group. So, these two studies are not consistent with the present study.[26] Although both methods are often used in obtaining experts’ consensus, research showed that nominal group method is superior to other methods or even Delphi technique from a different aspect. Therefore, nominal group was adopted in the present study.[19]

Albert, in her article, suggested evidence-based nursing care in cardiac failure patients. She selected the studies conducted between 1994 and 2005 using an evidence-based pyramid. She defined the care providers and receivers, and recommended evaluation of the guidelines suggested to the wards.[27] In the present study, clinical guideline quality was checked by AGREE questionnaire, which is consistent with the study of Burgers et al., which is on the level of the quality of clinical guidelines existing in oncology ward evaluated through AGREE questionnaire.[28] Vlayen et al., in a literature review, investigated the valid tools in designing a clinical guideline as the most common tool, was AGREE questionnaire.[5] Klazinga et al. conducted a study for accreditation of AGREE tool and investigated its ability to clarify the quality of clinical guidelines. They firstly collected 100 guidelines from 11 countries and separately investigated them with 194 experts. Then, the primary tool was modified, and three guidelines from each country were selected and investigated by 70 other experts. About 95% of them announced that AGREE was an appropriate tool to check the quality of nursing guidelines.[29]

Chen et al. measured the quality of seven guidelines by AGREE tool. In four clinical guidelines, the quality of applicability was less than the other sections, which is consistent with our study.[30] In our study, AGREE score was over 60% in all sections of the designed clinical guideline (showing a proper quality). Based on Chen et al., if AGREE score is over 60% in most of the tool sections, the guideline is recommendable. If the score is between 30 and 60%, it is conditionally recommended, and in case of less than 30% score, it is not recommended.

High number of questions in the second section of the questionnaire and high volume of clinical guideline in the third section were among the limitations of the present study, which led to delayed or no response of some experts. As neonatal palliative care is a new issue in Iran, the researchers faced shortage of experienced and adequately knowledgeable experts to be selected in the panel of experts.

CONCLUSION

Nurses need a clinical guideline to support the neonates and their parents concerning end-of-life palliative care. Researchers hope this guideline can be an efficient step toward improvement of care and nurses can well support the families with neonates’ end of life. With regard to increasing importance of palliative care, the present clinical guideline can fill the existing gap in the context of neonatal palliative care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article was derived from a master thesis of Zoafa A. with project number 392462 Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. The authors acknowledge the staffs’ support that made this project successful.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hommersom A, Lucas PJ, Van Bommel P. Checking the quality of clinical guidelines using automated reasoning tools. Theory and Practice of Logic Programming: 2008;8:611–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Wees P, Mead J. Brussels, Belgium: European Region of World Confederation for Physical Therapy; 2004. Framework for clinical guideline development in physiotherapy; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alanen S, Välimäki M, Kaila M. Nurses’ experiences of guideline implementation: A focus group study. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:2613–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohamadpor A. Tehran: Iran Medical Science University; 2009. Comparative standards of hospital hygiene standards of the International Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vlayen J, Aertgeerts B, Hannes K, Sermeus W, Ramaekers D. A systematic review of appraisal tools for clinical practice guidelines: Multiple similarities and one common deficit. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:235–42. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt-Taylor J. Clinical guidelines and care protocols. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2004;20:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.VandenBerg KA. Individualized developmental care for high risk newborns in the NICU: A practice guideline. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83:433–42. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harbour RT, Forsyth L. SIGN 50: A guideline developer's handbook. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. NHS Scotland. 2011:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghazali M, Erabi A, Gholamimotlagh F. Ethical issues in speacial situations. In: Eghbali M, Salehi S, editors. Ethics and law in nursing and midwifery. Isfahan, Iran: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 1391. p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Rooy L, Aladangady N, Aidoo E. Palliative care for the newborn in the United Kingdom. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menon BS, Mohamed M, Juraida E, Ibrahim H. Pediatric cancer deaths: Curative or palliative? J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1301–3. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, Weissman D. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1752–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid S, Bredemeyer S, van den Berg C, Cresp T, Martin T, Miara N, et al. Palliative care in the neonatal nursery. Neonatal, Paediatr Child Health Nurs. 2011;14:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahern K. What Neonatal Intensive Care Nurses Need to Know About Neonatal Palliative Care. Adv Neonatal Care. 2013;13:108–14. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3182891278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romesberg TL. Building a case for neonatal palliative care. Neonatal Netw. 2007;26:111–5. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.26.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kain V, Gardner G, Yates P. Neonatal palliative care attitude scale: Development of an instrument to measure the barriers to and facilitators of palliative care in neonatal nursing. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e207–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Lisle-Porter M, Podruchny AM. The dying neonate: Family-centered end-of-life care. Neonatal Netw. 2009;28:75–83. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.28.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boss RD. Palliative care for extremely premature infants and their families. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16:296–301. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadizadeh F, Kabiri P, Kelishadi R. Isfahan, Iran: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2010. Guideline for Development dan Adaptation of Clinical Practice Guidelines; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabriz: Urogynecology Knowledge management center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences; 1392. Urogynecology Knowledge management center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Clinical Guideline Localization Urinary Incontinence in women; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consortium AN. The Agree Research Trust. Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2009. Appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II. AGREE II Instrument. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catlin A, Carter B. Creation of a neonatal end-of-life palliative care protocol. Neonatal Netw. 2002;21:37–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.South Central Palliative Care Group. Guideline Framework for Neonatal Palliative (Supportive and End of Life) Care. In: Guideline Scnn, editor. South Central Network Quality Care Group South. 2013. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toman C, Harrison MB, Logan J. Clinical practice guidelines: Necessary but not sufficient for evidence-based patient education and counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;42:279–87. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadeq Tabrizi J, Gharibi F. Developing a national accreditation model via Delphi Technique. Hospital. 2012;11:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rolley JX, Salamonson Y, Wensley C, Dennison CR, Davidson PM. Nursing clinical practice guidelines to improve care for people undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Aust Crit Care. 2011;24:18–38. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert NM. Improving medication adherence in chronic cardiovascular disease. Crit Care Nurse. 2008;28:54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgers J, Fervers B, Haugh M, Brouwers M, Browman G, Philip T, et al. International assessment of the quality of clinical practice guidelines in oncology using the Appraisal of Guidelines and Research and Evaluation Instrument. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2000–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klazinga N. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: The AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen KH, Kao CC, Liu HE, Chiu WT, Kuo KN, Chen CC. Using appraisal of guidelines research and evaluation to appraise nursing clinical practice guidelines in Taiwan and to compare them to international studies. J Exp Clin Med. 2012;4:58–61. [Google Scholar]