Abstract

Purpose

Post-operative radiation therapy (RT) is recommended for patients with rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) having microscopic disease. Sometimes RT dose/volume is reduced or omitted in an attempt to avoid late effects, particularly in young children. We reviewed operative bed recurrences to determine if non-compliance with RT protocol guidelines, influenced local-regional control.

Methods

All operative bed recurrences among 695 Group II RMS patients on IRS I-IV were reviewed for deviation from RT protocol. Major/minor dose deviation was defined as > 10% or 6–10% of the prescribed dose (40–60 Gy), respectively. Major/minor volume deviation was defined as tumor excluded from the RT field or treatment volume not covered by the specified margin (pre-operative tumor volume and 2–5 cm margin), respectively. No RT was a major deviation.

Results

Forty-six of 83 (55%) patients with operative bed recurrences did not receive the intended RT (39 major and 7 minor deviations). RT omission was the most frequent RT protocol deviation (19/46 – 41%), followed by dose (17/46 – 37%), volume (9/46 – 20%), dose and volume deviation (1/46 – 2%). Only 7 operative bed recurrences occurred on IRS IV (5% local-regional failure) with only 3 RT protocol deviations. 63 (76%) patients with a recurrence died of disease despite retrieval therapy, including 13 of 19 non-irradiated children.

Conclusion

Over half the operative bed recurrences were associated with non-compliance; omission of RT was the most common protocol deviation. Three-fourths of children die when local-regional disease is not controlled, emphasizing the importance of RT in Group II RMS.

Keywords: Rhabdomyosarcoma, Radiation Therapy, Group II, Protocol Compliance, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Patients with rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) who have undergone gross total resection of the primary tumor but are left with positive surgical margins are staged as Group II. Post-operative radiation therapy (RT) is then recommended to target the operative bed, including resected positive regional lymph nodes. These patients also receive systemic chemotherapy. This multi-disciplinary approach, used in all Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group (IRSG) trials has resulted in a 5-yr failure free survival (FFS) of 73% with local recurrence rate of 8% and regional recurrence rate of 4% (1). Review of patterns of failure in these Group II patients show those most likely to relapse have clinical features including unfavorable histology, unfavorable site, positive nodes (subgroup IIb/IIc) and treatment on earlier IRS trials (1–5).

The rationale for post-operative RT is that chemotherapy alone is not able to eradicate microscopic disease, whereas moderate dose RT, directed at regions of known disease, does reduce the risk for local-regional recurrence. A large proportion of children with Group II RMS are less than 5 years of age, and some physicians or parents are reluctant to accept RT because of perceived deleterious side effects. In some cases, the recommended radiation dose or volume is reduced or omitted altogether resulting in a higher potential for recurrence in the operative bed. The outcome as reported in the IRSG experience of Group II patients who relapse is poor. Pappo et al. estimate 5 year survival rates of 20% in patients with group II/III embryonal histology and 3% in patients with groups II-IV alveolar histology after relapse in patients with non-metastatic RMS (6). Although Pappo’s analysis included patients with distant as well as local-regional relapse and patients with more advanced stage tumors, it emphasizes the importance of optimizing systemic and localregional control at diagnosis.

To determine if deviation from radiation therapy guidelines is a factor contributing to operative bed recurrence among Group II patients, we reviewed local-regional failures in Group II patients with respect to compliance with the IRS I-IV defined RT protocol guidelines. Outcome after re-treatment for recurrence was also reviewed to determine the potential for retrieval in those with an operative bed recurrence.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients and Staging

Patients eligible for analysis included previously untreated patients, less than 21 years of age, with a biopsy proven rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), undifferentiated sarcoma (UDS), or sarcoma not otherwise specified (NOS) who were entered onto IRS I through IV protocols and staged as Group II according to the IRSG Surgical-Histopathologic Grouping System. All patients entered on IRS trials have been approved through Institutional Review Boards and procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation. Stage including subgroup (IIa, IIb, IIc) was verified by members of the IRSG surgical committee and was based on operative notes, pathologic and clinical information. In 65 cases the stage was reclassified as Group II after central review and included 20 patients initially enrolled on study as Group I (4 who received RT) and 45 patients enrolled as Group III (all whom received RT).

Radiation Therapy Guidelines

The RT guidelines for dose, treatment volume, and timing of radiation after surgery are outlined in Table 1. The recommended radiation dose by study included: IRS-I, 50–60 Gy, with a dose reduction to 40 Gy for children less than 3 years of age delivered at week 1; IRS-II, 40–45 Gy delivered at week 6; IRS-III 41.4 Gy delivered at week 2 for non-alveolar RMS or week 6 for alveolar RMS; IRS-IV 41.4 Gy delivered at week 9 except for those with an orbit/eyelid primary when treatment was delivered at week 1. The recommended treatment volume by study included: IRS-I, the initial tumor volume at the time of diagnosis plus the entire muscle bundle from origin to insertion; IRS-II, the tumor volume with a 5 cm margin; IRS-III, the tumor volume with a 5 cm margin, except in patients with a GU tumor where 2 cm margin was acceptable; and IRS-IV, the tumor volume with a 2 cm margin. Clinically uninvolved regional lymph nodes were not included in the radiation portals for subgroup IIa. The regional lymph node station was included in the radiation portal if the lymph nodes were surgically resected and were positive for sarcoma (subgroup IIb or IIc).

Table 1.

Dose, Volume, and Timing of Post-operative Radiation Therapy

| Dose (Gy) | Volume (cm) | Timing of radiation therapy with chemotherapy (weeks) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IRS-I | 50.0 – 60.0 (40.0 < 3 yrs of age) | TV + entire muscle bundle | 1 |

| IRS-II | 40.0 – 45.0 | TV + 5 | 6 |

| IRS-III | 41.4 | TV + 5 (except GU + 2) | 6 alveolar, 2 non-alveolar |

| IRS-IV | 41.4 | TV + 2 1 | orbit/eyelid, 9 all other primary sites |

TV - tumor volume GU - genitourinary cm - centimeters Gy - Gray

RT records of patients enrolled on IRS II-IV were reviewed at Quality Assurance Review Center (QARC). Prior to the founding of QARC, data review from IRS I was undertaken at the IRS statistical office. Clinical information and treatment data including simulation films and port films, radiation treatment records with total dose and fractionation were collected on all patients. Dosimetry with treatment planning data were also reviewed on IRS II-IV. A member of the IRSG Radiation Oncology committee reviewed all RT data. Patients were reviewed for compliance with the RT guidelines and evaluated for the dose of radiation delivered and volume irradiated and scored as to whether there was a deviation from the recommended guidelines. A major dose deviation was scored when the dose received was less than 10% of the protocol required dose and in those in whom RT was omitted. A minor dose deviation was scored when the dose received was within 6–10% of the protocol required dose. A major volume deviation was scored when the targeted tumor was not within the treated volume. A minor volume deviation included treatment field less than the protocol specified margin. For this analysis, we reviewed compliance with RT guidelines for dose and volume, but not dose uniformity and critical organ deviations, as uniformity of dose and dose volume histogram (DVH) data were not available on early IRS trials. The observed compliance rate with RT protocol guidelines for Group II patients treated on IRS II-IV is 70% and serves as a benchmark to compare RT compliance in the current analysis (Laurie, F. unpublished QARC data personal communication 2009). Local recurrence was defined as clinical or pathologic evidence of disease in the operative bed. For subgroup IIa, recurrence in the operative bed did not include regional node failure as only the primary tumor volume was irradiated for this subgroup. However for subgroup IIb or IIc where the resected regional nodal basin was included in the post-operative RT volume, operative bed recurrence could include local and/or regional relapse. In several patients there was both a concurrent local-regional failure as well as a failure outside of the operative bed (distant) and these patients were included in the analysis.

RESULTS

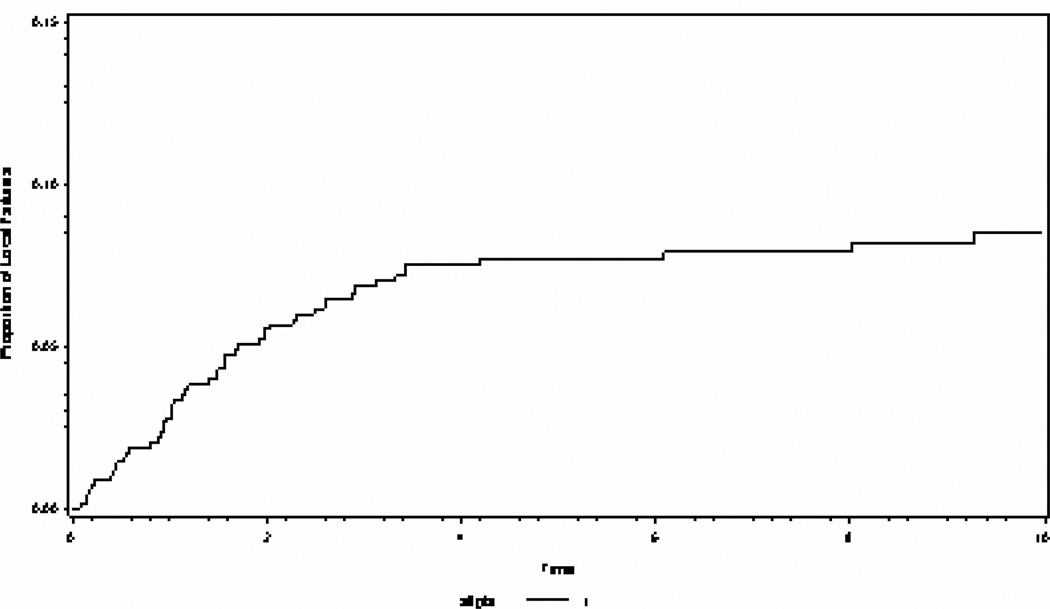

Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of 83 (12%) patients recurring within an operative bed among 695 patients with Group II RMS enrolled onto IRS-I (1972 to 1978, n=180), IRS-II (1978 to 1984, n=177), IRS-III (1984 to 1991, n=203), and IRS-IV (1991 to 1997, n=135). Eleven of the 83 operative bed recurrences were associated with a distant failure. Figure 1 shows the overall cumulative incidence of local failures among all group II patients.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of 83 Group II Patients with recurrence in operative bed

| IRS study | operative bed recurrence (n=83) |

|---|---|

| IRS I (n=180) | 19 |

| IRS II (n=177) | 29 |

| IRS III (n=203) | 28 |

| IRS IV (n=135) | 7 |

| Subgroup | |

| IIa (n=506) | 51 |

| IIb/IIc (n=189) | 32 |

| Age (years) | |

| < 2 (n=116) | 27 |

| 2 – 5 (n=238) | 19 |

| 6 – 10 (n=140) | 13 |

| 11–15 (n=119) | 16 |

| 16 (n=82) | 8 |

| Histology | |

| Botyroid /Embryonal (n=435) | 40 |

| Alveolar/UDS (n=260) | 43 |

| Primary Site | |

| Favorable (n=316) | 22 |

| Unfavorable (n=379) | 61 |

( ) number of patients within each category of the total 695 patients

Figure 1.

The cumulative incidence of local failure for all Group II patients over 10 years.

Over half of the patients with an operative bed recurrence were ≤ 5 years of age with the majority of these patients <2 years of age. The highest rate of operative bed recurrences occurred on IRS-II (16%) followed by IRS III (14%), IRS I (11%), with the lowest on IRS IV (5%). Of all patients with an operative bed recurrence those with unfavorable histology (43/260 – 17%) were more likely to recur compared with those with favorable histology (40/435 – 9%). Similarly patients with an unfavorable primary site were more likely to recur (61/379–16%) as compared with those with a favorable site (22/316–7%).

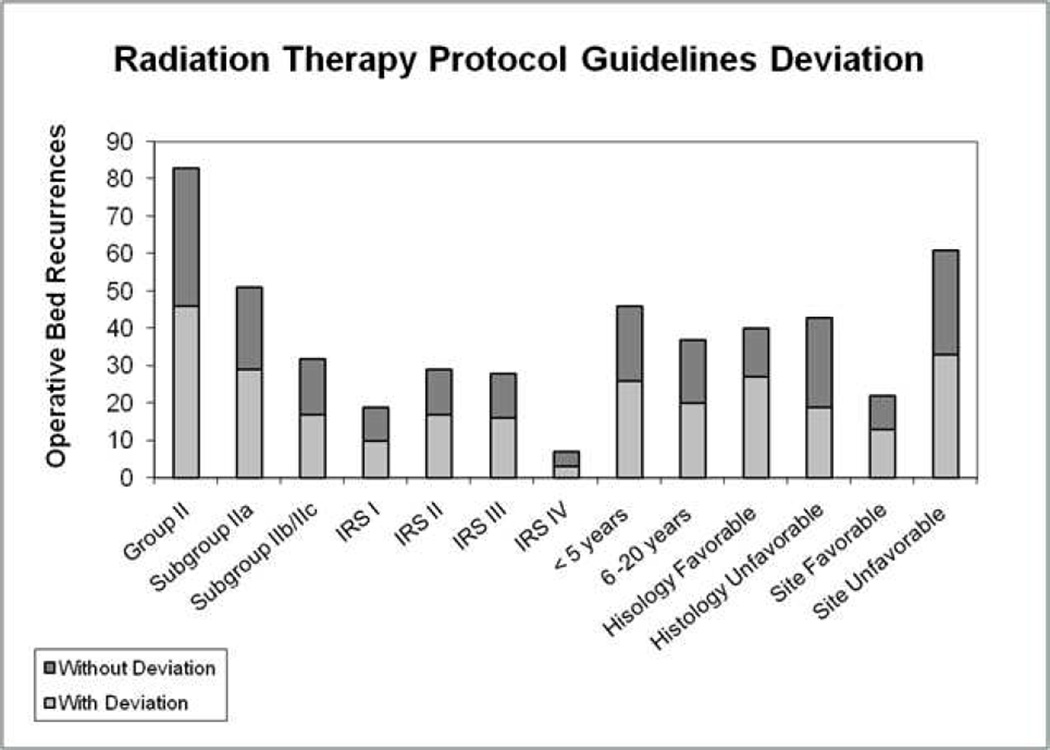

Figure 2 summarizes recurrences in the operative bed according to deviations from RT protocol guidelines. There were 83 patients with Group II tumors who had a recurrence within the operative bed; 46 (55%) did not receive the intended RT, 39 with major deviations (19 who did not receive RT) and 7 with minor deviations. Omission of RT was the most frequent RT protocol deviation (19/46) followed by dose (17/46), volume (9/46), dose and volume (1/46). In subgroup IIa there were 51 operative bed recurrences in 506 patients. Twenty-nine of 51 (57%) recurrences occurred in patients whose treatment deviated from the RT guidelines including 10 who did not receive RT, 10 with dose deviations (6 major and 4 minor), 4 with volume deviations (3 major and 1 minor), and 5 with both dose and volume deviations (all major). In subgroup IIb and IIc there were 32 recurrences in 189 patients. Seventeen of 32 (53%) operative bed recurrences occurred in patients whose treatment deviated from the RT guidelines, including 9 who did not receive RT, 2 with dose deviations (major), 5 with volume deviations (3 major and 2 minor), and 1 with both a dose and volume deviation (major).

Figure 2.

Absolute number of operative bed recurrences is depicted in relation to compliance with RT protocol guidelines. No deviation from protocol guidelines is in dark grey and deviation from protocol deviation is in light gray. The protocol compliance is depicted for all Group II patients, subgroups, IRS trial, age, histology and site.

According to age group, the most operative bed recurrences were observed in those ≤ 2 yrs of age accounting for 25 of 83 (30%) operative bed recurrences. Seventeen of 25 patients (68%) in this age group did not receive the intended RT for the following reasons: 10/17 cases RT was omitted, 4/17 RT dose was too low dose, 2/17 irradiated volume was too small and 1/17 had both too low a dose and too small a volume.

According to IRS trials: on IRS I - 10 of 19 (53%) operative bed failures were associated with non-compliance including 1 patient who did not receive RT; on IRS II - 17 of 29 (59%) operative bed failures were associated with noncompliance including 6 patients who did not receive RT; on IRS III - 16 of 28 (57%) operative bed recurrences were associated with non-compliance including 8 patients who did not receive RT; on IRS IV - 3 of 7 (43%) operative bed recurrences were associated with non-compliance including 1 patient who did not receive RT.

Of the 83 patients with an operative bed recurrence, 63/83 (76%) died. Mortality was similar among patients with a protocol deviation as those without protocol deviations. Thirteen of 19 (68%) of the non-irradiated children died of disease despite re-treatment at time of failure. The 20 surviving patients with an operative bed recurrence are disease free at least one year after re-treatment (range 1–23 years, median 6.4 years). Of these 20 survivors, 19 patients had a local only recurrence at the time of relapse. Only one patient from subgroup IIb/IIc who recurred in a lymph node station was successfully re-treated. Within subgroup IIa, 13 of 51 patients (25%) were disease free at 1–23 years after retreatment for local recurrence. Within subgroup IIb and IIc, 7 of 32 patients (22%) are disease free at 2.6–21 years after re-treatment for local recurrence (6 patients) or regional recurrence (1 patient). The number disease free after retreatment according to IRS trial included: IRS I - 3/19 (16%), IRS II - 5/29 (17 %), IRS III - 9/28 (32%), IRS IV 3/7 (43%).

Patients with favorable histology and a primary tumor in a favorable site comprised the majority of successful re-treatments with only one of 20 survivors having unfavorable histology. Of the 25 children ≤2 years of age with an operative bed recurrence only 6 are alive after re-treatment. These 6 patients had favorable histology (with the exception of 1 patient with alveolar histology) and local only recurrence at the time of relapse.

DISCUSSION

The operative bed recurrence rate for Group II patients treated on IRS I-IV is 12%. Less than half the Group II patients with an operative bed recurrence received the recommended RT. QARC statistics show an observed rate of 70% compliance with RT protocol guidelines of Group II patients treated on IRS II-IV protocols. These compliance rates are comparable to successor studies D9602 (low risk RMS protocol) and D9803 (intermediate risk RMS) (Laurie, F. unpublished QARC data personal communication 2009). These data suggest that adherence to RT guidelines would lead to fewer operative bed recurrences and improved local-regional control as observed on IRS IV where the local-regional control rate of 95% was associated with protocol compliance similar to what would be expected for all Group II patients (5).

The importance of optimizing radiation therapy delivery within the context of a controlled protocol has been demonstrated in pediatric cancer trials, including Ewing sarcoma and leukemia. Donaldson et al. reported 5 year 80% local control with strict adherence to RT guidelines on a multi-institutional Ewing sarcoma protocol as compared to 16% local control when major deviations from RT protocol guidelines were documented (7). Halperin et al. reviewed compliance with RT protocol guidelines on a Pediatric Oncology Group leukemia trial which used cranial RT, and reported improved compliance with RT guidelines over time with a trend toward greater compliance with the experience of the treating institution suggesting clinical expertise is relevant in RT delivery. A cranial RT field as administered in leukemia is a relatively simple RT field to simulate and treat (8). By contrast, RT planning and delivery for pediatric sarcomas is complex which emphasizes the difficulty of achieving uniform compliance in a multi-institutional trial. Detailed imaging studies and 3-D treatment planning are required in order to define tumor volumes in relation to normal tissue structures. Careful treatment planning is critical to the overall goal of organ preservation while maximizing local - regional control.

The major factor in this study, which influenced non compliance with RT guidelines, was young age. Since the majority of patients with RMS are children, not unexpectedly, over half the patients with an operative bed recurrence were less than 5 years of age, many less than 2 years of age. The most common protocol deviation was omission of RT leading us to believe that concern for latent normal tissue injury in very young patients was the reason for withholding RT.

Most RT dose violations were reported during the earlier IRSG studies where RT doses were the highest (up to 60 Gy). The majority of RT volume deviations associated with operative bed recurrence were seen in those patients with resected regional nodes (subgroup IIb and IIc) and were attributed to inadequate coverage of the regional lymph node stations. Patients in subgroup IIc have the greatest tumor burden of microscopic disease and are at greater risk for recurrence. Of note, there were no recurrences in subgroup IIc on IRS IV possibly due to improved staging and technologic advances in defining tumor volumes and compliance with radiation therapy delivery as well as improved education of participating radiation oncologists. As well, Baker et al reported that intensified chemotherapy on the IRS IV trial conferred an improved failure free survival in the subgroup with resected positive nodes and embryonal RMS arising at favorable sites, suggesting chemotherapy may also contribute to decreasing local regional recurrence (9).

Outcome after local-regional recurrence is poor with fewer than 25% of patients in our study alive after retreatment. Only thirteen percent of the patients with an operative bed recurrence had a concurrent distant failure. As operative bed recurrence is infrequently associated with distant metastasis optimizing local-regional control at diagnosis appears to be an effective strategy to achieve high cure rates for Group II patients. Schuck et al. for the Cooperative Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group (CWS) reported the results of Group II RMS patients treated on 81, 86, 91, and 96 trials to determine if RT was necessary and reported inferior local control and EFS when RT was omitted. No subgroup could be defined that produced equivalent outcomes to patientswho were irradiated (10).

The IRSG experience has reported poor outcome for patients with non-metastatic RMS (Group I-III) after relapse with 8 month median survivals (6). A favorable subset has been identified who have an improved prognosis after relapse (50% 5 year survival) and include patients with low stage and group, favorable histology and favorable site at diagnosis. The Italian soft tissue sarcoma group reported that, in addition to the favorable clinical characteristics, treatment factors such as local only relapse, and relapse off therapy are predictive for improved prognosis and longer survival (11). The few patients in our study who were successfully re-treated fit this profile and included those with favorable histology and favorable site of disease and local only relapse. We can also add that retrieval therapy on contemporary protocols is better (43% IRS IV vs 16% IRS I), presumably from earlier detection and management of operative bed recurrence and improved therapeutic options for retrieval.

Some institutions have reported that no prior RT at the time of initial diagnosis may yield improved chance for retrieval therapy to be successful. Dantonello et al. reported patients with non-metastatic RMS with smaller tumor size (<5 cm) and no RT as predicting for improved retrieval (12). The patients in our study in whom RT was omitted did not have superior retrieval rates, as compared to those who did receive RT.

A strength of this study is the large number of patients, uniformly managed with long term follow-up. In addition, we were able to conduct a thorough review of compliance with RT guidelines using the central data repository at QARC enabling meticulous technical review of the quality of administered RT and compliance of treatment plans by pediatric radiation oncologists. The centralized review process through QARC has contributed to improvements with compliance, particularly physician adherence to RT guidelines and submission of data.

An inherent weakness of a retrospective review is the recognition that treatment dating back to the 1970’s does not meet current standards. Furthermore, the accuracy of institutional reporting of local regional recurrences and clinical outcomes has improved with time.

A limitation of this study is that we evaluated RT compliance only in those Group II patients who recurred in the operative bed. Another approach would be to review local control according to RT deviations in all Group II patients. It is possible that there were many deviations from RT guidelines in patients who did not recur in the operative bed. However since one of our objectives was to determine outcome after recurrence, particularly among those in whom RT was omitted, we chose to focus solely on this select group of patients. Another limitation is that dose and volume guidelines changed over time so what would have been scored acceptable on one study could be a major violation if treated on a different IRS study with different guidelines. For example, a >10% dose deviation for an IRS-I patient required to receive 50 Gy would have been scored a major violation if they received 40–44 Gy whereas if they were treated on IRS III-IV the same patient would have been in compliance.

The current direction in treatment for Group II patients is stratification into a low or intermediate risk treatment protocols depending on pre-treatment factors such as histology and location of primary tumor (13). Currently chemotherapy is less intensive for the low risk group while RT doses and volumes (dose range 36 – 41.40 Gy) are the same for both groups. Moderate dose RT with conformal techniques should limit radiation exposure to normal tissues to minimize injury to normal tissues and organs.

Future directions for patients with RMS having microscopic disease are to determine the optimal RT dose and volume specific to the disease site, histology and age of patient as well as timing with respect to surgery. Additionally, we anticipate the use of 3-dimensional treatment planning with contemporary technology such as proton beam radiation therapy and imaged guided radiation therapy will improve the accuracy and quality of radiation treatment delivery for all pediatric patients (14, 15).

CONCLUSIONS

Operative bed recurrence in children with microscopic residual disease is associated with a lower rate of RT protocol guideline compliance than would be expected for Group II patients treated on rhabdomyosarcoma protocols as reviewed at QARC. Omission of RT accounts for over 40% of the RT protocol deviations. Since three-quarters of local-regional relapses in Group II patients are not successfully re-treated, we continue to recommend chemotherapy and RT for all such patients. Future studies should focus on defining the minimal dose and volume necessary to treat children with rhabdomyosarcoma with microscopic disease.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Department of Health and Human Services, United States Public Health Service grants no. CA-24507 CA-72989, CA-29511 and CA-98543.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith LM, Anderson JR, Qualman S, et al. Which patients with rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) and microscopic residual tumor (Group II) fail therapy? A report from the soft tissue sarcoma committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4058–4064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.20.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurer HM, Beltangady M, Gehan EA, et al. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-I. A final report. Cancer. 1988;61:209–220. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880115)61:2<209::aid-cncr2820610202>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurer HM, Gehan EA, Beltangady M, et al. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-II. Cancer. 1993;71:1904–1922. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930301)71:5<1904::aid-cncr2820710530>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crist W, Gehan EA, Ragab AH, et al. The Third Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:610–630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crist W, Anderson J, Meza JL, et al. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-IV: results for patients with non-metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3091–3102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pappo AS, Anderson JR, Crist WM, Wharam MD, et al. Survival after relapse in children and adolescents with rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(11):3487–3493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donaldson SS, Torrey M, Link MP, et al. A multidisciplinary study investigating radiotherapy in Ewing’s sarcoma: End results of POG #8346. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42(1):125–135. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halperin EC, Laurie F, Fitzgerald TJ. An evaluation of the relationship between the quality of prophylactic cranial radiotherapy in childhood acute leukemia and institutional experience: a Quality Assurance Review Center - Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Int. J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(4):1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02833-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker KS, Anderson JR, Link MP, et al. Benefit of Intensified Therapy for patients with local or regional embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma: Results for the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2427–2434. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuck A, Mattke AC, Schmidt B, et al. Group II Rhabdomyosarcoma and Rhabdomyosarcoma like Tumors: Is Radiotherapy necessary? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):143–149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzoleni S, Bisogno G, Garaventa A, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors after recurrence in children and adolescents with non metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2005;104(1):183–190. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dantonello TM, Int-Veen C, Winkler P, et al. Initial patient characteristics can predict relapse in localized Rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):406–413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raney BR, Maurer HM, Anderson JR, et al. The Intergroup Study Group (IRSG): major lessons from the IRS-I through IRS-IV studies as background for the current IRS-V treatment protocols. Sarcoma. 2001;5:9–15. doi: 10.1080/13577140120048890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchant TE. Proton Beam Therapy in Pediatric Oncology. Cancer J. 2009;15(4):298–305. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181b6d4b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beltran C, Lukose R, Gangadharan B, et al. Image quality and dosimetric property of an investigational imaging beam line MV-CBCT. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2009;10(3):3023–3036. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v10i3.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]