Abstract

Exercise-induced dyspnea (EID) is a common complaint in young athletes. Exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB) is the most common cause of EID in healthy athletes, but it is important to recognize more serious pathology. Herein we present the case of an 18-year-old woman with a 1.5-year history of EID. She had been treated for EIB without relief. Her arterial oxygen saturation was 88% during exercise testing. Computed tomographic angiography to assess for vascular abnormalities identified a large thrombus in the main pulmonary trunk. Symptoms markedly improved with therapeutic anticoagulation. Massive pulmonary embolus is an exceedingly rare etiology of exertional dyspnea in young athletes. Hypoxemia during exercise testing was an important clue that something more ominous was lurking that required definitive diagnosis.

Exercise-induced dyspnea (EID) is a common complaint in young athletes. Exertional dyspnea in young, otherwise healthy and active individuals can be challenging to diagnose and treat. Exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB) is recognized as the most common cause of EID in otherwise healthy athletes (1). Patients with EIB typically experience wheezing, chest tightness, coughing, and dyspnea that is due to transient narrowing of the airways (bronchospasm) during or shortly after exercise (2). EIB affects approximately 10% to 15% (3) of the general population. Athletes (particularly varsity and elite athletes) show a much higher prevalence, around 40% (4, 5). The diagnosis of EIB is often made on the basis of self-reported symptoms without objective testing. This approach is neither sensitive nor specific (6). It is important for clinicians to recognize that EID in healthy adolescent athletes may have causes other than asthma (7). Alternative causes of EID should be sought when other symptoms of asthma are not present, bronchodilators do not completely prevent or promptly relieve EID, and baseline pulmonary function is normal (8). Correct diagnosis will not only prevent the use of medications destined to fail but will occasionally uncover potentially life-threatening disease. Herein we present a case of a young athlete with EID who was initially misdiagnosed and treated empirically for EIB, which led to delayed diagnosis of a life-threatening disease.

CASE DESCRIPTION

An 18-year-old woman presented to an outpatient cardiology clinic for evaluation of exertional dyspnea worsening over the past 1.5 years. Her medical history was significant for the diagnosis of exercise-induced asthma treated with as-needed short-acting bronchodilators. Her only other medication was an oral contraceptive (desogestrel-ethinyl estradiol 0.15–30 mg–mcg). She did not use tobacco, alcohol, or recreational or performance-enhancing drugs. She was an active athlete participating in varsity basketball, volleyball, and track. Approximately 1.5 years prior to presentation, she developed sudden worsening dyspnea with minimal exertion and associated presyncope. Symptoms were provoked by 5 minutes of aerobic exertion and relieved with <5 minutes of rest. She did not experience wheezing, and albuterol did not provide relief. Her blood pressure was 102/56 mm Hg; heart rate, 52 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; resting oxygen saturation, 99% breathing ambient air; and body mass index, 21.3 kg/m2. She was physically fit, in no distress, and had no conversational dyspnea. Cardiac and pulmonary exams were normal. Her abdomen was soft, nontender, nondistended, and without masses or organomegaly. There was no peripheral edema; peripheral pulses were full and equal bilaterally. Further, there was no calf tenderness, and Homman's sign was absent.

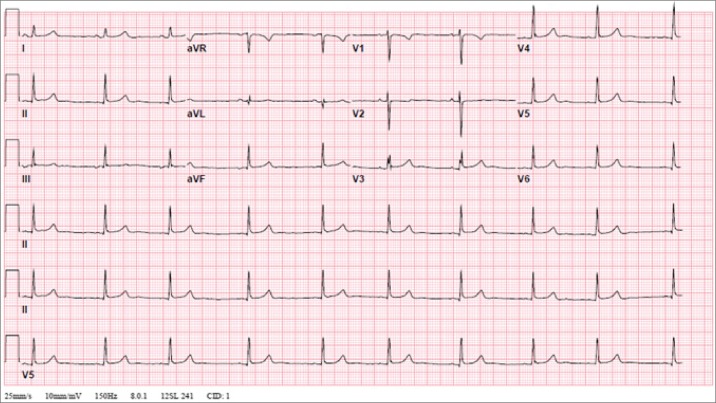

Initial laboratory data revealed normal serum electrolytes, blood counts, and renal and liver function. Quantitative D-dimer was 0.42 ug FEU/mL (normal <0.48 ug FEU/mL). Chest x-ray showed subtle findings, including elevation of the left hemidiaphragm and a Westermark sign (cutoff of the left main pulmonary artery) (Figure 1). An electrocardiogram showed sinus bradycardia, normal intervals and voltage, and no ST segment abnormalities (Figure 2). Pulmonary function testing showed normal spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusing capacity; there was no change with bronchodilator. Resting transthoracic echocardiogram showed the left ventricular ejection fraction to be 60% to 65%. There was mild tricuspid regurgitation (maximum regurgitant velocity of 2.26 m/s), and the estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 25 mm Hg. Right ventricular basal diameter was 42 mm (normal ≤ 42 mm); mid ventricle, 32 mm (normal ≤ 35 mm); and longitudinal length, 56 mm (normal ≤ 86 mm) (Figure 3). Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was 16.4 mm (abnormal ≤ 16 mm), and systolic excursion velocity was 10.57 cm/s (abnormal ≤ 10 cm/s).

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray showing cutoff of the left pulmonary artery, Westermark sign (arrow), and elevation of the left hemidiaphragm.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram demonstrating sinus bradycardia (heart rate 56 bpm), normal intervals and voltage, and no ST segment or T wave abnormalities.

Figure 3.

Transthoracic echocardiogram with an apical four-chamber view at end diastole demonstrating right ventricle (RV) dimensions at the upper limit of normal; an RV diameter at the base of 42 mm; mid ventricle 32 mm; and long axis 56 mm. The function of the left ventricle (LV) was normal.

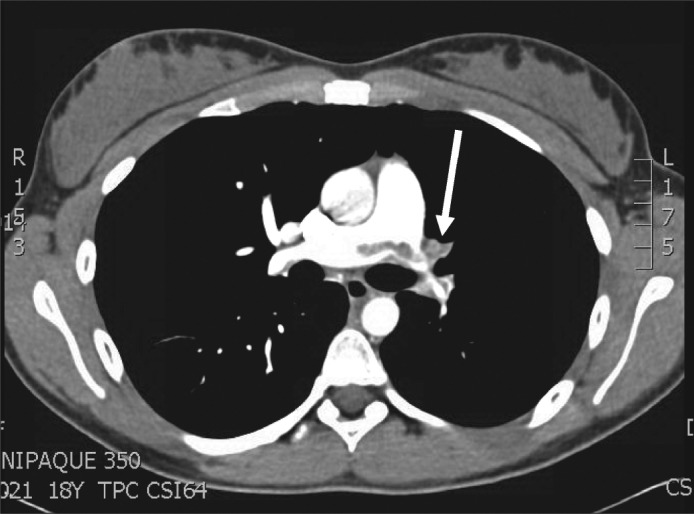

The patient exercised for 5:32 minutes on a Bruce treadmill protocol (maximum speed 3.4 mph, 14% grade). She reached 6.2 metabolic equivalents. Her maximum heart rate was 170 beats/min (84% of her age-predicted maximum). Arterial oxygen saturation was 88% at peak exercise. Computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest showed a large intraluminal thrombus within the left main pulmonary artery extending into the right and left pulmonary arteries (Figure 4). The left pulmonary artery was completely occluded (Figure 5). Protein C activity was 116% (normal 70%–130%), protein S activity was 70% (normal 55%–123%), and antithrombin III activity was 92% (normal 80%–120%). Assays for cardiolipin IgG, IgM, and IgA were within the normal range. Two tests for lupus anticoagulant were negative (DRVVT screen and PTT-Lupus reagent). There was no evidence of activated protein C resistance. DNA testing for Factor V Leiden and prothrombin II gene mutations were negative.

Figure 4.

CT angiogram demonstrating a large intraluminal filling defect in the main pulmonary trunk (arrow) extending into both the right and left pulmonary arteries. Note the paucity of vascular markings over the left lung field.

Figure 5.

CT angiogram with three-dimensional volume rendering in the anterior and posterior view demonstrating the absence of left pulmonary artery (PA) circulation.

Therapeutic anticoagulation was started with warfarin. After 6 weeks of anticoagulation, she noted marked improvement in functional capacity, nearly back to previous baseline. A follow-up CT angiogram at 8 weeks showed marked improvement in thrombus burden.

DISCUSSION

Massive pulmonary embolus (PE) is an exceedingly rare etiology for exertional dyspnea in young athletes. Young athletes often do not present with classic symptoms associated with PE; thus, these patients are often treated for a number of other conditions before the correct diagnosis is reached (9). Hypoxemia during exercise testing was an important clue that something more ominous was lurking. Normal pulmonary function testing (spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusing capacity) make primary lung pathology less likely. Causes of exertional dyspnea with hypoxia in a young athlete (with healthy lungs) are typically related to vascular abnormalities usually resulting in right-to-left shunting or large ventilation-perfusion defects (functional right-to-left shunt). Important considerations include anomalous venous return (10), intrapulmonary arteriovenous malformations (11), and intravascular obstruction (such as PE). Large occlusive PEs cause a functional right-to-left shunt. Shunting occurs due to severe ventilation-perfusion mismatch, which results in a large increase in total dead space with adjacent areas of excess perfusion (12). Shunting is more pronounced in the presence of an atrial septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus as pulmonary pressure increases (due to increased pulmonary vascular resistance) flow through the defect increases.

The test of choice for the diagnosis of pulmonary vascular disorders is pulmonary angiography and chest CT (13, 14). Once PE has been confirmed, interventions are targeted at disruption of the coagulation cascade to minimize ongoing thrombosis. Therapeutic anticoagulation is the mainstay of therapy. In patients with high-risk PEs (particularly cardiogenic shock and/or persistent arterial hypotension), thrombolysis, percutaneous catheter embolectomy and fragmentation, and/or surgical embolectomy should be considered. A major clinical decision in our patient is the duration of anticoagulation. Indefinite anticoagulation reduces the risk of subsequent venous thromboembolism by approximately 90%; the major disadvantages are increased risk of bleeding and the inconvenience of anticoagulation over the lifetime of our young patient (15, 16).

Plasma levels of D-dimer increase in the presence of acute thrombi. D-dimer has a low positive predictive value but a high negative predictive value. Barring laboratory error, our patient's negative D-dimer may be due to chronic organized thrombus or may simply be a false negative.

Our patient was investigated for hypercoagulable conditions with entirely normal results. The only identifiable risk factor for thromboembolism was the use of a combined oral contraceptive preparation. She had been taking an oral contraceptive prior to symptom onset and continued it until the time of diagnosis. While oral contraceptives increase the risk of venous thromboembolic disease by about 3 to 6 times that of similar patients not taking them, the absolute risk is still quite low, at 3 to 4 per 10,000 woman-years (17). The relative risk of thromboembolism in patients using oral contraceptives is about half that of pregnancy (18). A progestin-only preparation would be an appropriate substitution for future contraception while minimizing the risk of recurrent thromboembolism in a patient such as ours. (Our patient opted to forego hormonal prophylaxis.)

While EIB is the most common cause of EID in young athletes, it is imperative that physicians recognize alarming features that may suggest more serious underlying pathology. Massive PE is an exceedingly rare etiology of exertional dyspnea in otherwise healthy young athletes. Appropriate and timely intervention can prevent serious morbidity and mortality.

References

- 1.Koehle M, Lloyd-Smith DR, McKenzie DC. Exertional dyspnea in athletes. Br Columbia Med J. 2003;45(10):508–514. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfrey S, Anderson SD, Silverman M. Physiologic aspects of exercise-induced asthma. Chest. 1973;63(Suppl):365–375. doi: 10.1378/chest.63.4_supplement.36s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seear M, Wensley D, West N. How accurate is the diagnosis of exercise induced asthma among Vancouver schoolchildren? Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(9):898–902. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.063974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feinstein RA, LaRussa J, Wang-Dohlman A, Bartolucci AA. Screening adolescent athletes for exercise-induced asthma. Clin J Sport Med. 1996;6(2):119–123. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons JP, Kaeding C, Phillips G, Jarjoura D, Wadley G, Mastronarde JG. Prevalence of exercise-induced bronchospasm in a cohort of varsity college athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(9):1487–1492. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180986e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rundell KW, Im J, Mayers LB, Wilber RL, Szmedra L, Schmitz HR. Self-reported symptoms and exercise-induced asthma in the elite athlete. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(2):208–213. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Löwhagen O, Arvidsson M, Bjärneman P, Jörgensen N. Exercise-induced respiratory symptoms are not always asthma. Respir Med. 1999;93(10):734–738. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(99)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abu-Hasan M, Tannous B, Weinberger M. Exercise-induced dyspnea in children and adolescents: if not asthma then what? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(3):366–371. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60989-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehle M, Lloyd-Smith DR, McKenzie DC. Exertional dyspnea in athletes. Br Columbia Med J. 2003;45(10):508–514. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valencia PA, Oeckler RA, Taggart NW, Bonnichsen CR. Levoatriocardinal vein: an unusual cause of hypoxemia in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014:A4842. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss P, Rundell KW. Imitators of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2009;5(1):7–15. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldhaber SZ, Elliott CG. Acute pulmonary embolism: part I: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis. Circulation. 2003;108(22):2726–2729. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097829.89204.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remy J, Remy-Jardin M, Giraud F, Wattinne L. Angioarchitecture of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: clinical utility of three-dimensional helical CT. Radiology. 1994;191(3):657–664. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.3.8184042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, Agnelli G, Galiè N, Pruszczyk P, Bengel F, Brady AJ, Ferreira D, Janssens U, Klepetko W, Mayer E, Remy-Jardin M, Bassand JP. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2008;29(18):2276–2315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Research Committee of the British Thoracic Society Optimum duration of anticoagulation for deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet. 1992;340(8824):873–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulman S; Duration of Anticoagulation Study Group The effect of the duration of anticoagulation and other risk factors on the recurrence of venous thromboembolisms. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1999;149(2–4):66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandenbroucke JP, Rosing J, Bloemenkamp KW, Middeldorp S, Helmerhorst FM, Bouma BN, Rosendaal FR. Oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(20):1527–1535. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105173442007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss G. Risk of venous thromboembolism with third-generation oral contraceptives: A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 2):295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]