Abstract

Objectives To describe the content of non-public complete response letters issued by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when they do not approve marketing applications from sponsors (drug companies) and to compare them with the content any subsequent press releases issued by those sponsors

Design Cross sectional study.

Data sources All applications for which FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research initially issued complete response letters (n=61) from 11 August 2008 to 27 June 2013. Complete response letters and press releases were divided into discrete statements related to seven domains and 64 subdomains and assessed to determine whether they matched.

Results 48% (29) of complete response letters cited deficiencies in both the safety and efficacy domains, and only 13% cited neither safety nor efficacy deficiencies. No press release was issued for 18% (11) of complete response letters, and 21% (13) of press releases did not match any statements from the letters. Press release statements matched 93 of the 687 statements (14%), including 16% (30/191) of efficacy and 15% (22/150) of safety statements. Of 32 complete response letters that called for a new clinical trial for safety or efficacy, 59% (19) had matching press release statements. Seven complete response letters reported higher mortality rates in treated participants; only one associated press release mentioned this fact.

Conclusions FDA generally issued complete response letters to sponsors for multiple substantive reasons, most commonly related to safety and/or efficacy deficiencies. In many cases, press releases were not issued in response to those letters and, when they were, omitted most of the statements in the complete response letters. Press releases are incomplete substitutes for the detailed information contained in complete response letters.

Introduction

When the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declines to approve an application to market a drug, it informs the sponsor (the drug company) sin a complete response letter.1 2 These letters systematically document deficiencies that FDA reviewers have identified and typically explain corrective actions sponsors can take.

With limited exceptions, the public does not receive a full account of the FDA’s reasons for disapproval because complete response letters are part of unapproved applications that FDA regulations generally treat as confidential.3 4 5 Some have called on the FDA to publicly disclose the complete response letters, arguing this would ensure a more accurate portrayal of their reasoning and would allow sponsors, researchers, and clinicians to learn from previous scientific and regulatory failures.6 7 8 Currently the European Medicines Agency publishes refusal assessment reports detailing its reasons for denying applications.9 Some members of the pharmaceutical industry, however, have opposed the disclosure of any information that could be considered proprietary and confidential and have suggested that the release of complete response letters would provide an advantage to competitors.10

Sponsors might issue press releases for complete response letters they receive, presumably, in part, because US securities laws require companies to disclose information that investors would be substantially likely to consider important in making investment decisions.11 By aggregating data for all recent complete response letters so that sponsors and specific drug products are not identifiable, we characterized the reasons cited by the FDA for not approving drug marketing applications and the degree to which sponsors’ public statements reflected those complete response letters. Given the distinct purpose and usual brevity of press releases, we would not expect that they would necessarily cover all components of complete response letters issued by the FDA.

Methods

Identification and categorization of complete response letters

We obtained complete response letters for all drugs (in this paper, the term “drugs” refers to drugs and biological products regulated by CDER) that were the subject of applications classified as new molecular entities (that is, drugs that contain active moieties that the FDA has not previously approved). The complete response letters for new drug applications were obtained from the FDA’s Document Archiving, Reporting, and Regulatory Tracking system, and those for the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research-regulated biologics licensing applications (BLAs) were obtained from the economics staff in the FDA’s office of planning. The study covered new drug applications and biologics licensing applications from 11 August 2008, when the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research began issuing complete response letters, to 27 June 2013. We included only the first letter for a given new drug or biologics licensing application, thus excluding letters issued after sponsors responded to initial letters by resubmitting applications. One letter dealing with two indications for the same new molecular entity was treated as two separate letters. We excluded from the study supplemental new drug applications (for new indications, dose forms, doses, packaging, and labeling for already approved drugs), abbreviated new drug applications (for generic drugs), and applications for radiologic agents (such as contrast media).

We categorized sponsors as either privately or publicly held using the Bloomberg Businessweek website.12 We used the site’s symbol lookup function to search for sponsor names under the “public” and “private” search fields. These results were then confirmed by searching for the company name in the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system, which includes filings only from public companies.13 We considered sponsors to be publicly traded if they were listed as such in Bloomberg Businessweek and were also listed in the Securities and Exchange Commission’s electronic data gathering, analysis, and retrieval. Conversely, a sponsor was considered private if Bloomberg Businessweek listed them as such and they did not appear in the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system. We did not identify any discrepancies between these two sources. If company websites and press releases revealed a sponsor to be a subsidiary of a larger company, we used the parent company’s status. We used the Dun and Bradstreet business information database,14 which characterizes sponsors as either “large” or “small” using the cutoff of 750 employees used in the small business administration classification of business size.15

We used the FDA’s document archiving, reporting, and regulatory tracking system and data provided by FDA’s economics staff to determine the date that complete response letters were issued, application status as of 27 June 2013, date of subsequent approval (if applicable), review priority granted to the application (standard or priority), and “first-in-class” status (drugs with a new and unique mechanism of action for treating a medical condition). We defined an orphan drug as one designated as such in FDA’s online orphan drug product designation database16 for the proposed indication in the application. The FDA website also indicates whether an application was referred to an advisory committee before the complete response letters were issued. Posted minutes from public advisory committee meetings on applications discuss the conclusions the committee reached. We classified these conclusions as favoring approval if the committee majorities either explicitly favored approval, stated that both safety and efficacy had been demonstrated, or concluded that the benefits of the products outweighed their risks, a method consistent with previous research on advisory committee voting.17

Identification of press releases

We identified press releases issued by sponsors that described complete response letters through publicly available sources, including the sponsors’ websites and internet search engines (Google, Yahoo, Bing, PRNewswire.com, and Drugs.com). Search terms were a combination of the drug’s proprietary and non-proprietary names and one of the following terms, in succession: “news release,” “press release,” “PR,” “complete response,” and “CRL.” We also entered drug names into the full text document search function of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system18 to search all US filings, including quarterly and annual reports, for any suggestion that press releases had been issued. If these sources did not identify associated press releases, we contacted sponsors directly via mail to request copies, stating that if we did not receive correspondence from them claiming otherwise by a designated date, we would assume that no press release had been issued.

Coding of content of complete response letters

We divided the contents of complete response letters into discrete “statements” describing specific application deficiencies. We defined statements as portions of complete response letters conveying single concepts. We then assigned each statement to one of seven mutually exclusive domains (see fig 2) based on the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use E319 as well as an assessment of 10 complete response letters included in the study that an investigator not participating in final statement extraction and coding had reviewed. These domains were designed to reflect the deficiency categories the FDA typically uses in complete response letters, although they do not use a uniform approach for conveying deficiencies.

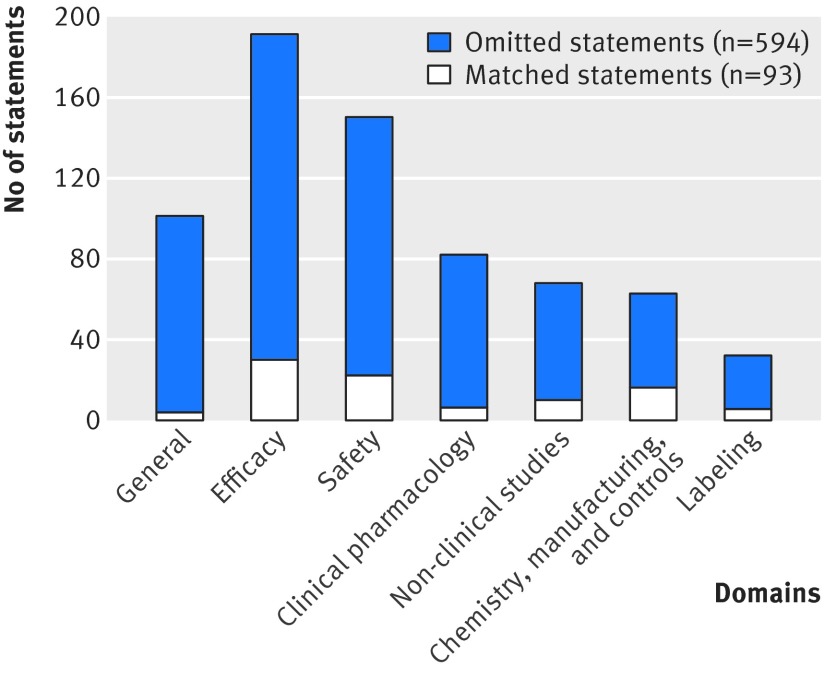

Fig 2 Statements in press releases issued by sponsors matched to and omitted from those in complete response letters issued by FDA regarding non-approval of new drugs by domain

Some sentences from complete response letters contained multiple statements. For example, a letter might state in a single sentence that neither safety nor efficacy had been satisfactorily demonstrated. We classified this as two statements—one relating to safety and the other to efficacy. Conversely, multiple, even non-adjacent sentences, could describe a single deficiency.

Each statement was further assigned to one of 64 subdomains, again based on the International Conference on Harmonisation E3 and the review of 10 complete response letters. If necessary, statements were partitioned to reach a level of detail sufficient to permit assignment to single subdomains. Statements that could reasonably be assigned to more than one subdomain were assigned to the more specific subdomain. We aggregated similar statements in the chemistry, manufacturing, and controls and labeling domains to generate no more than one statement per subdomain in each letter because those statements were often considerably longer and more detailed than those in other domains. Any statements that were part of the standard template (for example, informing a sponsor that it had a year to respond to the letter or that the drug product could not be marketed until the sponsor was notified in writing that the application was approved), or that otherwise did not correspond to a deficiency in the application (for example, acknowledgment of something the sponsor had successfully demonstrated), were not considered statements for the purposes of this analysis.

Identification of matching statements

Any press release statements that covered the same issues as statements in corresponding complete response letters were recorded as “matching” the letter statements and were assigned to the same domains and subdomains as the letter statements. Press release statements were not required to provide the same level of detail as letter statements to be considered a match and were sometimes divided into two or more statements to maximize statement matching rates. For complete response letters that lacked corresponding press releases, all letter statements were considered to have been omitted. We also collected data on press release statements that did not appear in complete response letters. These specific categories were also identified through an initial review of 10 press releases during development of the study protocol.

Data analysis

A single investigator identified the particular statements in complete response letters and press releases, classified them into domains and subdomains, and, when appropriate, matched press release statements to letter statements. The principal investigator then reviewed all statements and their classifications. These two investigators reconciled all disagreements directly.

We compared the lengths of complete response letters and press releases using the word count feature in Microsoft Word. These counts included all text in complete response letters related to application deficiencies but excluded introductions, page headers, and wording common to all letters regarding labeling, the need to keep safety information current, and deadlines for resubmission. Word counts of press releases excluded safe harbor statements, notes to editors, and media contact information.

The primary outcomes analyzed were the number and percentage of complete response letters with deficiencies in each of the domains and subdomains and the number and percentage of such statements that appeared in the associated press releases. We examined the relation between company, drug, and review process characteristics and whether a press release was issued; whether the press release matched any letter statements; the proportion of letter statements that were matched in associated press releases; and whether the press release contained at least one letter statement recommending a new clinical trial for safety or efficacy.

Frequencies and cross tabulations were performed with the built in functions of Microsoft Access. We calculated relative risks and 95% confidence intervals using MedCalc online statistical software.20 Differences between means were analyzed with a two tailed Student’s t test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in this study.

Results

Characteristics of complete response letters

A total of 61 complete response letters (48 new drug applications and 13 biologics licensing applications) met our inclusion criteria (table 1). Ninety seven new drug and biologics licensing applications without a prior complete response letter were approved during the study period. Applications for which complete response letters were issued and those that were approved without first receiving a letter were similar with respect to application type (that is, new drugs versus biologics), sponsorship by a publicly traded company, company size, and orphan status. Applications with priority review status, however, were less likely to receive a complete response letter (relative risk 0.43, 95% confidence interval 0.25 to 0.75). Drugs referred to advisory committees were marginally more likely to be the subject of a letter (1.45, 0.97 to 2.17), although favorable advisory committee votes were associated with a lower probability of issuance of a complete response letter (0.34, 0.22 to 0.50).

General characteristics of all complete response letters (CRLs) and predictors of matching.* Figures are numbers (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| All CRLs (n=61) | CRLs with at least one matched PR statement(s) (n=37) | CRLs with no matched statements† (n=24) | Relative risk‡ (95% CI) or P value for mean | All statements (n=687) | Matched statement(s) (n=93) | Omitted statements† (n=594) | Relative risk‡ (95% CI) or P value for mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application type: | ||||||||

| New drug | 48 (79) | 28 (58) | 20 (42) | 0.84 (0.55 to 1.30) | 536 (78) | 75 (14) | 461 (86) | 1.17 (0.73 to 1.90) |

| Biologics | 13 (21) | 9 (69) | 4 (31) | 151 (22) | 18 (12) | 133 (88) | ||

| Sponsor: | ||||||||

| Publicly traded | 52 (85) | 36 (69) | 16 (31) | 6.23 (0.97 to 39.90) | 575 (84) | 91 (16) | 484 (84) | 8.86 (2.22 to 35.45) |

| Private | 9 (15) | 1 (11) | 8 (89) | 112 (16) | 2 (2) | 110 (98) | ||

| Large (>750 employees) | 46 (75) | 25 (54) | 21 (46) | 0.68 (0.47 to 0.98) | 472 (69) | 38 (8) | 434 (92) | 0.31 (0.22 to 0.46) |

| Small (<750 employees) | 15 (25) | 12 (80) | 3 (20) | 215 (31) | 55 (26) | 160 (74) | ||

| Drug type: | ||||||||

| Orphan drug | 17 (28) | 13 (76) | 4 (24) | 1.40 (0.96 to 2.04) | 214 (31) | 36 (17) | 178 (74) | 1.40 (0.95 to 2.05) |

| Not an orphan drug | 44 (72) | 24 (55) | 20 (45) | 473 (69) | 57 (13) | 416 (87) | ||

| Review: | ||||||||

| Priority | 12 (20) | 8 (67) | 4 (33) | 1.13 (0.71 to 1.79) | 139 (20) | 17 (12) | 122 (88) | 0.88 (0.54 to 1.44) |

| Standard | 49 (80) | 29 (59) | 20 (41) | 548 (80) | 76 (14) | 472 (86) | ||

| Class type: | ||||||||

| First-in-class | 20 (33) | 14 (70) | 6 (30) | 1.25 (0.84 to 1.85) | 229 (33) | 36 (16) | 193 (84) | 1.26 (0.86 to 1.86) |

| Not first-in-class | 41 (67) | 23 (56) | 18 (44) | 458 (67) | 57 (12) | 401 (88) | ||

| Referred to advisory committee before CRL issuance: | ||||||||

| Yes | 35 (57) | 22 (63) | 13 (37) | 1.08 (0.72 to 1.65) | 421 (61) | 62 (15) | 359 (85) | 1.26 (0.84 to 1.89) |

| No | 26 (43) | 15 (58) | 11 (42) | 266 (39) | 31 (12) | 235 (88) | ||

| Advisory committee favors approval: | ||||||||

| Yes | 18 (53) | 11 (61) | 7 (39) | 0.98 (0.58 to 1.66) | 163 (40) | 27 (17) | 136 (83) | 1.26 (0.79 to 2.03) |

| No§ | 16 (47) | 10 (63) | 6 (38) | 244 (60) | 32 (13) | 212 (87) | ||

| Mean (range) days from start of review cycle to issuance of CRL | 313 (179-579) | 322 (181-579) | 299 (179-396) | P=0.26 | 312 (179 to 579) | 330 (181 to 579) | 309 (179 to 579) | P=0.53 |

| Application result: | ||||||||

| Subsequently approved | 25 (41) | 17 (68) | 8 (32) | 1.22 (0.82 to 1.82) | 228 (33) | 38 (17) | 190 (83) | 1.39 (0.95 to 2.04) |

| Withdrawn or pending | 36 (59) | 20 (56) | 16 (44) | 459 (67) | 55 (13) | 404 (87) | ||

| Mean (range) days from issuance of CRL to approval of application (if approved) | 448 (25, 95-1309) | 408 (17, 127-1309) | 532 (8, 95-1126) | P=0.38 | 546 (228, 95 to 1309) | 454 (38,127 to 1309) | 564 (190, 95 to 1309) | P=0.02 |

*Percentages in columns 2 and 6 are column percentages. All other percentages are row percentages.

†Includes 11 complete response letters without associated press releases.

‡Calculated as proportion of drugs with characteristic with match divided by proportion without characteristic with match.20

§Percentages in this row consider only complete response letters and statements associated with applications that went to advisory committee before letter issuance. One advisory committee was not directly asked whether new drug application should be approved.

We observed a median of four domains per complete response letter. Seven percent (n=4) of letters included deficiencies in all seven domains, and 8% (n=5) had deficiencies in only a single domain. The domains most commonly implicated were safety (at least one statement in 69% (n=42) of letters), chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (69%, n=42), and efficacy (67%, n=41). Nearly half (48%, n=29) of letters had deficiencies in both the safety and efficacy domains, while only 13% (n=8) had neither safety nor efficacy deficiencies.

Characteristics of press releases and matching rates

We were unable to identify associated press releases for 11 of the 61 complete response letters. We received responses to our mailed inquiries related to five of these 11 drugs, all of which confirmed that no press releases were issued. All press releases identified were released within one week of the letter (median of 1 day), except for two that were published after 15 and 42 days, one of which announced that the drug was no longer being developed. After we excluded standardized language, complete response letters and press releases differed greatly in length, with a median word count of 1151 (range 99-5974) for the 61 complete response letters (the median was similar for just the 50 complete response letters with associated press releases) and 193 (78-532) in press releases.

New drug applications were less likely than licensing applications for biologics to have press releases associated with complete response letters (relative risk 0.79, 95% confidence interval 0.66 to 0.95); all biologics licensing applications had associated press releases. Having a publicly traded sponsor was the only other significant predictor of issuance of a press release among the company, drug, and review process characteristics listed in the table (2.71, 1.07 to 6.86).

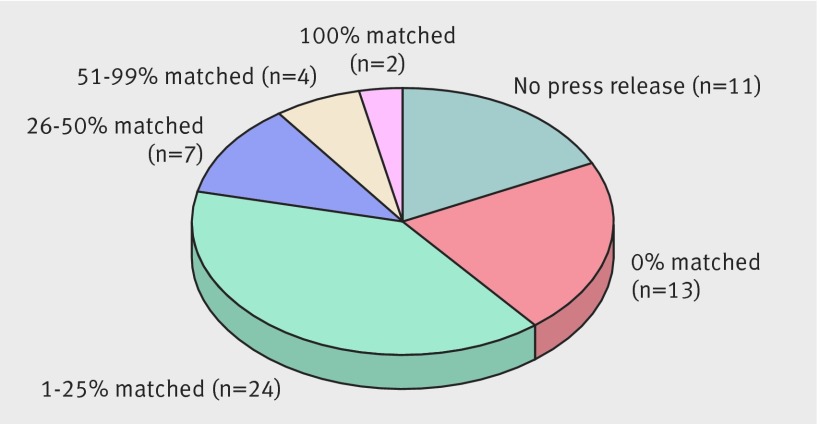

Thirteen additional press releases (21%) had no statements matching those in their associated complete response letters. Eleven of these press releases included at least one statement that did not appear in associated letters. The two other press releases were short documents (110 and 117 words) that included no content qualifying as a statement for the purposes of this study. Thirty seven press releases (61% of complete response letters) included one or more statements matching letter statements (fig 1).

Fig 1 Complete response letters issued by FDA regarding non-approval of new drugs and percentage of statements matched by associated press releases issued by sponsors (n=61)

Complete response letters and press releases: analysis overview of statements

We identified 687 statements in all 61 complete response letters (median eight statements per letter; range 1-38). As shown in figure 2, the most frequent statements were in the efficacy domain (191 statements; median 4 and maximum 17 per letter), followed by the safety domain (150 statements; median 3 and maximum 11). Together these two domains accounted for half of all letter statements.

Ninety three (14%) of the 687 statements in the 61 complete response letters were matched in press releases. The median number of matched statements was one (range 0-10), and the median number of omissions per letter was seven (0-38). Matching at the statement level was higher among public companies and lower among larger companies; the same characteristics that predicted whether a letter had at least one matching statement (table). No characteristic, however, was associated with a matching rate exceeding 26% at the statement level. The statements most likely to be omitted from press releases were general statements (96% (97/101) omitted) and clinical pharmacology statements (93% (76/82) omitted; fig 2). The domain with the highest matching rate was chemistry, manufacturing, and controls, with 25% (16/63) of letter statements matched. The matching rates for efficacy and safety (16% (30/191) and 15% (22/150), respectively) were similar to the overall matching rate, although 56% (52/93) of all matching statements were in these domains.

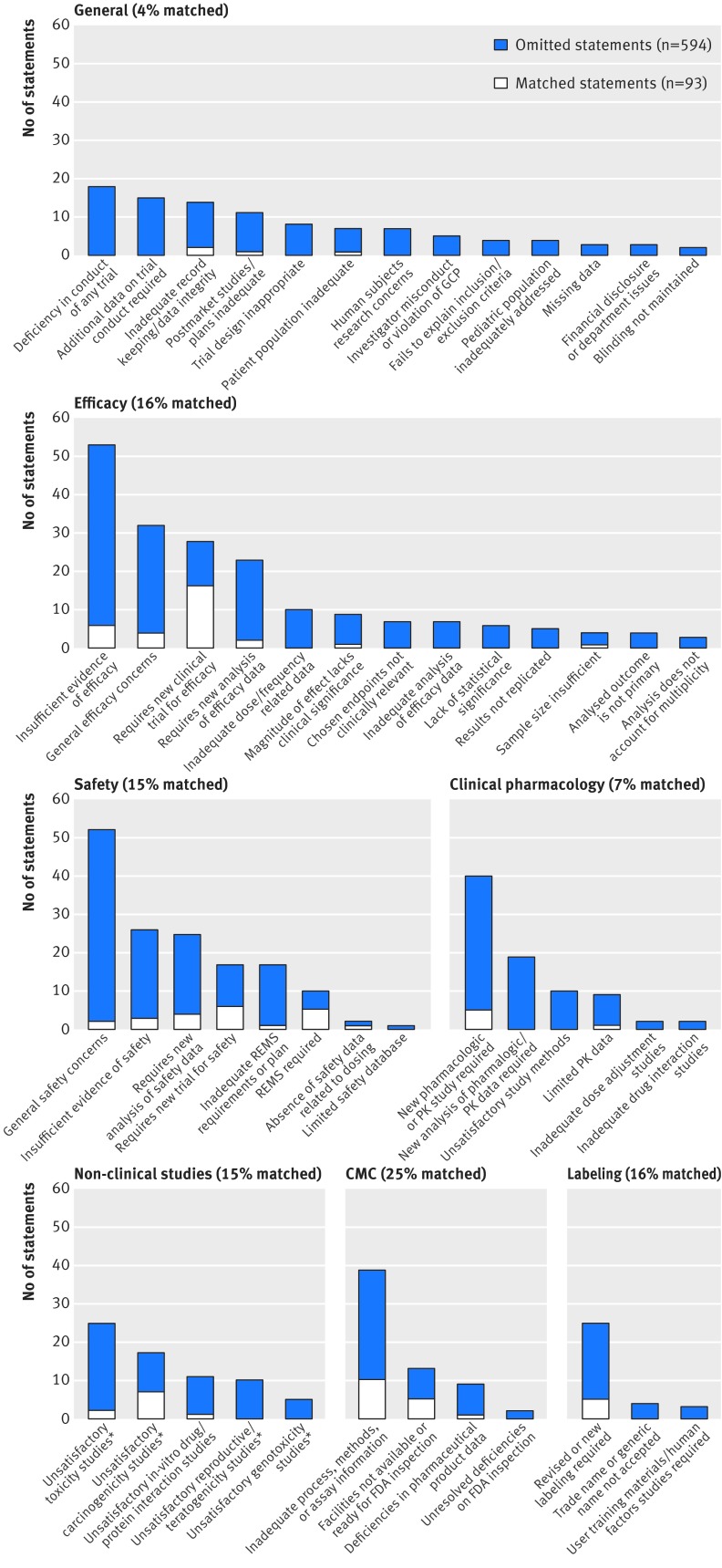

Figure 3 shows the number of matched and omitted statements by subdomain. The most common efficacy subdomain was “insufficient evidence of efficacy” (29 complete response letters, 53 statements), followed by general efficacy concerns (17 letters, 32 statements). The most frequently matched efficacy subdomain was “requires new clinical trial for efficacy” (57% of 28 statements matched); there were more matched statements in this subdomain (16 statements) than all other efficacy subdomains combined (14 statements).

Fig 3 Number of matched and omitted statements in press releases issued by sponsors compared with statements in FDA complete response letters by subdomain, arranged by domain. Overall matching rate for each domain is shown in parentheses. CMC=chemistry, manufacturing, and controls; GCP=good clinical practices; PK=pharmacokinetic; REMS=risk evaluation and mitigation strategy. *Represents four merged subdomains: requires new study; study suggests lack of safety; study/data not satisfactory; and requires new analysis of data

Within the safety domain, complete response letters most commonly contained general safety concerns (28 complete response letters, 52 statements, 4% (n=2) matched). Other commonly cited safety deficiencies included “insufficient evidence of safety” (18 letters, 26 statements, 12% (n=3) matched), “requires new analysis of safety data” (14 letters, 25 statements, 16% (n=4) matched), and “requires new trial for safety” (15 letters, 17 statements, 35% (n=6) matched). We observed higher matching rates in the subdomains “risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) required” (50%) (5/10) and “requires new trial for safety.” Seven complete response letters indicated that a clinical trial had a higher mortality rate in treated participants than in control groups, but only one of these statements had a matching press release statement.

Thirty two complete response letters (52%) contained at least one statement indicating that the FDA recommended a new trial for either safety or efficacy. Nineteen of the press releases associated with these 32 complete response letters (59%) had at least one matching statement on safety/efficacy trial recommendation. No company, drug, or review characteristic was associated with the presence of this statement. The statement level matching rate was 49% (22/45).

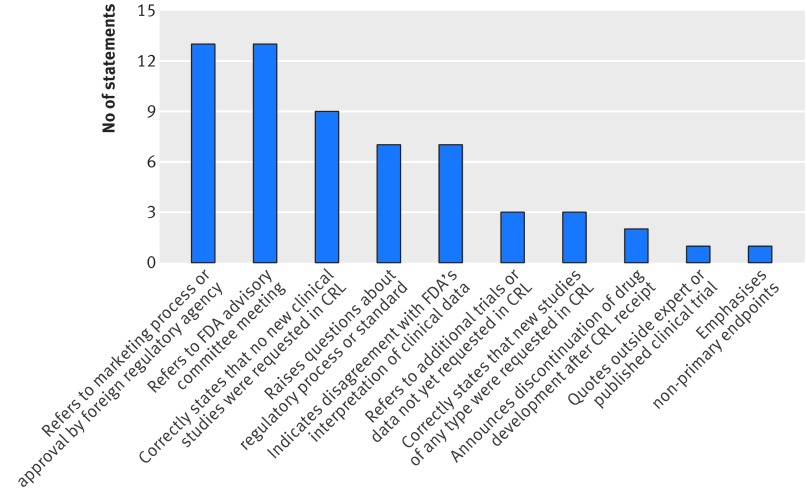

Many press releases (36%, n=22) had one or more statements that could not be matched to a statement in the complete response letter, with a total of 59 such statements, or 39% (59/152) of all press release statements (fig 4). Twelve percent (n=7) of such statements raised questions about the regulatory process or standard or expressed disagreement with the FDA’s interpretation of clinical data, and 5% (n=3) referred to data that the FDA neither reviewed nor cited in the letter.

Fig 4 Statements appearing in press releases issued by sponsors but not in associated FDA complete response letters regarding non-approval of new drugs (n=59)

Impact of Securities and Exchange Commission disclosures

To determine whether companies might be using alternative routes to disclose the information in complete response letters, we searched the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system and identified 35 annual, quarterly, or foreign reports related to the study drugs that mentioned complete response letters (57% of all letters). Of the 33 letters with both press releases and commission reports mentioning complete response letters, only seven Securities and Exchange Commission filings (21%) included a statement with more information from the complete response letter than the press release, and this information would have produced only eight additional matches with complete response letters, increasing the statement matching rate from 14% (n=93) to 15% (n=101). Thus, the Securities and Exchange Commission mentions of complete response letters were sometimes absent and, in general, less detailed than the letters.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our analysis found that the FDA’s reasons for not approving marketing applications for new molecular entities are not being fully conveyed to the public. The FDA issues complete response letters for a wide variety of substantive reasons (median of eight statements in a median of four domains). Safety and/or efficacy concerns were identified in 87% of complete response letters, and half of all statements in these letters referred to safety or efficacy. There was no associated company issued press release for 18% of these letters and no matching statement for an additional 21%. Overall, press releases referred to only 14% of the statements in the full set of complete response letters. Inclusion of certain Securities and Exchange Commission reports increased the matching rate to 15%.

Reasons for non-approval

The applications for which complete response letters were issued were not distinguishable from applications approved without complete response letters with respect to company and drug characteristics (for example, public trading status, company size, or being a first-in-class drug), but applications were distinguishable based on certain characteristics related to their review by FDA. Drugs for which complete response letters were issued were less likely to be priority review drugs, more likely to have been referred to an advisory committee, and less likely to have received a favorable advisory committee vote if they were referred.

A previous analysis of 151 applications for new molecular entity that received a complete response letter from 2000 to 2012 found that applications with efficacy deficiencies were more likely never to be approved (relative risk 2.24 (95% confidence interval 1.50 to 3.34), by our calculation).21 That study also found that deficiencies in safety and efficacy were primary reasons for non-approval (53% and 76% of applications, respectively). It differed from ours in that it reported the primary reasons for the non-approval of the application, based on the complete response letters, FDA action letters, reviews, and correspondence. In contrast, we relied exclusively on complete response letters and did not attempt to assign primary reasons for non-approval. The earlier study did not compare matching rates between complete response letters and press releases.

Matching

Only 15% of safety and efficacy statements were matched, similar to the 12% matching rate in the five other domains. Most findings associating the drug with a higher mortality rate went unmentioned in press releases. Press releases, however, were more likely to convey whether the FDA recommended a new trial for safety or efficacy reasons (49% matched) than other deficiencies. Statements that were included in press releases were typically accurate, even though they were generally less detailed than statements in FDA letters. In general, press releases from publicly traded (and small) companies were more likely to communicate content of complete response letters, suggesting that disclosure requirements from the US Securities and Exchange Commission might be an important driver of disclosure.

Clearly, the primary purpose of a press release is not to reveal every deficiency the FDA identifies; they are almost always considerably shorter and less technical than complete response letters. Nonetheless, they remain the predominant source of publicly available information regarding complete response letters; to our knowledge, no sponsor chose to release a complete response letter included in this study, although nothing prevents one from doing so.

Policy considerations

In 2009, the FDA released its transparency initiative, which aimed to provide information regarding the agency and its work to the public and regulated industry. In 2010, their transparency task force proposed that “FDA should disclose the fact that the Agency has issued a . . . complete response letter . . . and should, at the same time, disclose the . . . complete response letter,” and sought public comment on this proposal.22 Our analysis of the content of press releases indicates that they are incomplete substitutes for the detailed information contained in complete response letters. Disclosure of letters would allow the FDA to increase the overall transparency of its regulatory processes, providing greater awareness of the agency’s role in protecting health and combating misperceptions regarding the basis for non-approval of a drug. It would also allow for broader and more informed public discussion by relevant stakeholders (such as patients, clinicians, researchers, and public health advocates) of the scientific and regulatory reasons for the FDA’s actions. The need for increased transparency, however, must take into consideration the legal requirement to protect sponsors’ trade secrets and confidential business information.

We suggest three potential approaches to reducing the gap between the information provided in complete response letters and that provided in press releases. Sponsors could release the complete response letters themselves, although they did not choose to do so for any of the letters in this study. Sponsors could issue more complete press releases. Finally, the FDA could itself make the complete response letters public, although this would likely require a change in FDA’s regulations. A thorough discussion of these options is beyond the scope of this paper.

Strengths and limitations of study

We recognize several limitations of this study. First, we did not seek to characterize the accuracy of each particular statement in the press releases. Second, our reported matching rates might overstate the correspondence between complete response letters and press releases. Division of complete response letters into relatively specific statements and allowing press release statements to qualify as matching even if they were not as comprehensive as corresponding letter statements tends to maximize matching rates. For example, one letter statement detailed a request for a new efficacy trial in 110 words, including “you will need to provide satisfactory results from another adequate and well-controlled trial in patients with [disease] demonstrating the effect of [drug] on a short-term measure . . .” while the corresponding press release noted in 17 words that the letter recommended an additional clinical trial. Moreover, we limited chemistry, manufacturing, and controls and labeling statements to one per subdomain for each letter because of the length and level of detail of these statements. This was meant to avoid overemphasizing these potentially less substantial deficiencies, but it also had the effect of increasing matching rates, as even a limited mention of an issue related to these subdomains would have qualified as a match.

Third, the practice of assigning statements in complete response letters and press releases to domains and subdomains is inherently subjective and potentially limits the reproducibility of this research. The practice of finely dividing statements, however, enhances reproducibility, two authors reviewed all assignments, and, given the robust findings, minor reassignments are unlikely to affect the fundamental conclusions. Finally, we included only complete response letters issued by FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and our results cannot be extrapolated to other FDA centers involved in product approvals.

Conclusions and policy implications

We have shown that the FDA issues complete response letters to sponsors for multiple substantive reasons, most commonly related to safety and efficacy. There are substantial differences in content between confidential complete response letters and press releases issued by sponsors. Our analysis suggests that press releases are generally an incomplete source of reasons for FDA non-approval of applications. The potential benefits of publicly disclosing the agency’s detailed rationale for refusing approval include better informing the development of new drugs, facilitating a richer public health discourse, and counteracting misconceptions regarding FDA’s reasons for denial of applications.

What is already known on this topic

The FDA issues complete response letters to sponsors when the agency determines that it cannot approve their marketing applications

Sponsors might choose, but are not required, to issue press releases indicating that FDA has issued a complete response letter

These press releases are often the only public source of information describing FDA’s decisions and rationales for not approving marketing applications

What this study adds

FDA generally issues complete response letters to sponsors for multiple, substantive reasons, most commonly related to safety and/or efficacy

In many cases, press releases are not issued in response to complete response letters

When they are issued, they omit most of the reasons the FDA cited for denying applications

Press releases are incomplete substitutes for the detailed information contained in complete response letters

We acknowledge the contributions of Aurel Iuga and Robert Temple in initial study design development, Michael Lanthier for the provision of certain data on drug approvals, and Robert Temple, Michael Lanthier, and Leonard Sacks for reviewing earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Contributors: PL conceived the study, oversaw data analysis, and played a leading role in drafting the manuscript. HSC helped conceive the study, designed the data collection instrument and reviewed all complete response letters and press releases with PL. DWS contributed to study design and write-up. SS contributed data analysis and portions of the first draft of the manuscript. JS prepared portions of the first draft of the manuscript. BD conducted the analysis related to the Securities and Exchange Commission. PL is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h2758

References

- 1.Complete response letter to the applicant, 21 CFR 314.110.

- 2.Complete response letter to the applicant, 21 CFR 601.3

- 3.Availability for public disclosure of data and information in an application or abbreviated application, 21 CFR 314.430.

- 4.Confidentiality of data and information in applications for biologics licenses, 21 CFR 601.51.

- 5.Trade secrets and commercial or financial information which is privileged or confidential, 21 CFR 20.61.

- 6.Gottlieb S. The FDA is evading the law. Dow Jones, Wall Street Journal, 2010. www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704034804576025981869663212.

- 7.Roy A. Bringing sunshine into the FDA’s black box. Forbes, 2010. www.forbes.com/sites/sciencebiz/2010/05/20/bringingsunshine-into-the-fdas-black-box.

- 8.Goldstein J. Why secrecy still shrouds FDA drug rejections. Dow Jones, Wall Street Journal, 2008. http://blogs.wsj.com/health/2008/08/07/why-secrecy-still-shrouds-fda-drug-rejections.

- 9.European Medicines Agency (EMA). Procedural advice on publication of information on negative opinions and refusals of marketing authorisation applications for human medicinal products. EMA, 2013 (EMA/599941/2012). www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2009/10/WC500004188.pdf.

- 10.Harris G. Drug agency may reveal more data on actions. New York Times, 1 June 2009. www.nytimes.com/2009/06/02/health/policy/02fda.html?scp=1&sq=gardiner%20and%20heartburn&st=cse.

- 11.TSC Industries, Inc. v. Northway, Inc., 426 US 438 (1976).

- 12.List of public and private companies. Bloomberg Businessweek, 2013. http://investing.businessweek.com/research/common/symbollookup/symbollookup.asp.

- 13.Company search. US Securities and Exchange Commission, 2013. www.sec.gov/edgar/searchedgar/companysearch.html.

- 14.D&B business information. Dun and Bradstreet, 2013. www.dnb.com.

- 15.Small Business Administration. Table of small business size standards matched to North American industry classification system codes. SBA, 2013. www.sba.gov/content/small-business-size-standards.

- 16.Search orphan drug designations and approvals. US Food and Drug Administration, 2013. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd.

- 17.Lurie P, Almeida CM, Stine N, Stine AR, Wolfe SM. Financial conflict of interest disclosure and voting patterns at Food and Drug Administration drug advisory committee meetings. JAMA 2006;295:1921-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Full-text search. US Securities and Exchange Commission, 2013. https://searchwww.sec.gov/EDGARFSClient/jsp/EDGAR_MainAccess.jsp.

- 19.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: structure and content of clinical study reports (E3). ICH, 1995. www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E3/E3_Guideline.

- 20.MedCalc Statistical Software [computer program on CD-ROM]. Version 12.7.7 for Windows. www.medcalc.org.

- 21.Sacks LV, Shamsuddin HH, Yasinskaya YI, Bouri K, Lanthier M, Sherman RE. Scientific and regulatory reasons for delay and denial of FDA approval of initial applications for new drugs, 2000-2012. JAMA 2014;311:378-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA transparency initiative: draft proposals for public comment regarding disclosure policies of the US Food and Drug Administration (proposal 13). FDA, 2010. www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/Transparency/PublicDisclosure/GlossaryofAcronymsandAbbreviations/UCM212110.pdf.