Abstract

Background:

Research literature has documented the nature of stigma associated with mental illness (MI) and its consequences in all spheres of life of ill persons and their families. It is also suggested that there is a need to develop intervention strategies to reduce stigma. However, very little is reported about these initiatives in the Indian context.

Aim:

To understand the nature of stigma associated with MI in a rural and semi-urban community in India and to develop an intervention package and study its impact.

Materials and Methods:

The study adopted a pre- and post-experimental/action research design with a random sample of community members including persons with chronic MI and their caregivers from rural and semi-urban areas. A semi structured interview schedule was used to assess the nature of stigma. An intervention package, developed on the basis of initial findings, was administered, and two post assessments were carried out.

Results:

Stigmatized attitude related to various aspects of MI were endorsed by the respondents. Caregivers had less stigmatizing attitude than the members of the community. Postintervention assessments (PIAs) revealed significant changes in attitudes towards some aspects of MI and this improved attitude was sustained during the second PIA, that is, after 3 months of intervention.

Conclusion:

People in the rural and semi-urban community have stigmatizing attitude toward MI. Intervention package focusing on the relevant aspect of MI can be used for reducing stigma of MI.

Keywords: Community attitude, intervention strategies, mental illness, stigma

INTRODUCTION

Stigma is a negative differentiation attached to some members of society who are affected by some particular condition or state.[1] “The term stigma connotes a deep mark of shame and degradation carried by a person as a function of being a member of a devalued social group.”[2] The stigmatized individual experiences social distancing, fear, rejection and ill treatment from others in the society. Mental illness (MI) lends itself to varied kinds of devaluation resulting in stigmatization and discrimination against a person with far reaching consequences. As per WHO consensus statement “Stigma results from a process whereby certain individuals and groups are unjustifiably rendered shameful, excluded and discriminated against.”[3]

Stigma of MI is exhibited by individuals, families, social groups, communities and societies. Associated stigma becomes an obstacle in the development of mental health care services and in ensuring a good quality of life for those with MI. Stigma robs people of rightful opportunities for housing, employment, socialization, and marriage.[4,5] Stigma associated with MI has been found to have an impact on the general health care system. It has been shown that people with MI receive fewer medical services than those without such a label.[6] Stigma of MI also affects those closely associated with the mentally ill person, that is, family members, friends, service providers and others. This phenomenon needs to be understood in personal as well as social context.

Considering the wide impact of stigma of MI, the underlying mechanisms related to stigma must be addressed, and the efforts must be made at all possible levels. Researchers suggest public awareness and education as important strategies to reduce stigma.[7,8,9] Common community level efforts to de-stigmatize MI have involved public education, which have reported beneficial changes.[10] The 1996 initiative of World Psychiatric Association to increase awareness and knowledge about schizophrenia and its treatment, and to improve public attitude towards those having schizophrenia yielded positive results.[11] Community-based programs have also used nontraditional methods like theatre plays and drama, peer-support training, education, media based programs, and involving community agencies (community leaders, influential political leaders) in the related activities.[12]

In India, fear of stigma is understood as a primary reason for not availing timely medical intervention for MI. Identification of common misconceptions, appropriate dissemination of information to dispel the same and building awareness in the community can go a long way in reducing stigma. With this in view the present community-based study was carried out. The study was planned to identify the nature of stigma, and develop a community-based intervention package. It was assumed that such an intervention is likely to reduce stigma in the community leading to acceptance and willingness to avail mental health services ensuring better treatment outcome for the mentally ill persons in the community.

Objectives

To assess the nature of stigma associated with chronic MI in a rural and semi-urban community

To develop an intervention package for reducing stigma in the community

To use the intervention package in the community

To assess the effect of the intervention package on the stigma of MI in the community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted by Richmond Fellowship Society, Bangalore, India at Chikaballapur Taluk situated at a distance of about 70 km from Bangalore on National Highway 7 spread over 223 villages and one town. The sex ratio in the Taluk is 969 female per 1000 male population. Majority of the population are agriculturists, the main crop being potatoes and mulberry used for making silk yarn. The population of the Taluk as per 2001 census was 184,226 comprising of 129,288 people living in rural and 54,938 people living in semi-urban areas. Commonly spoken languages are Kannada and Telugu. As per the Asset Index[13] 26.2% fall in the Upper Middle Economic group, 57.0% fall in the Lower Middle Economic group and 12.8% fall in the Poor Economic group. Only 4% belong to the Rich Economic category. Nuclear families constituted 56.7% of the population and joint, and extended families constituted 43.3% of the population.

The study adopted a pre- and post-intervention research design. The study was carried out in 4 phases.

Phase I

Study sample

A random sample of fifty villages and semi-urban areas (sample units) were selected using census list[14] as the sampling frame. The method adopted for randomization was probability proportional to sample size

Within each selected sample unit, a 10% systematic random sample of households were selected for the survey of community members. Sampling frame for selection of household was obtained from the Anganwadi workers household survey register

- Cases of those with MI and their caregivers were identified through medical records at the Primary Health Centers, and from the records of Mental Health Camp run RFS Siddhlagatta rural branch, from Anganwadi workers and also using snow-balling technique. In addition, information was collected from the community leaders and the families of mentally ill persons. Following three groups of members participated in the study. Other members in the community constituted the community group.

- Community members in general

- Caregivers of the mentally ill persons

- Mentally ill persons.

Persons with chronic mental illness

Persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (all types), Bipolar Affective Disorder, Major Depression, Chronic Anxiety disorders, and dual diagnosis (as available from their latest medical records and prescriptions) with duration of illness of at least 2 years and who need continuing care for long periods. There are primary caregivers, that is, who had been taking care of the ill person for not <6 months constituted another group, that is, Caregivers of the mentally ill persons. The members in this group were interviewed either at their residence or the camp site.

Phase I also included training the recruited staff in interviewing and using the tools for the study. Both didactic and on the field training were provided to the staff.

Tools used

Following tools were used during this phase

Case History Form along with a symptom checklist for persons with MI

A semi-structured interview schedule developed in an earlier study.[15] This instrument was tested on 1000 patients in four major cities of India as part of the Indian initiative of World Psychiatric Association program to reduce stigma and discrimination. The final tool was the result of factor analysis of the original tool. The first part of the tool elicits sociodemographic information and the second part measures stigma and discrimination experiences. The third section elicits information about measures to reduce stigma and discrimination. For the present study, three separate sets of schedules were prepared for the three groups of respondents and the questions were restructured accordingly. This was used to assess the nature of stigma Appendix I.

Cases of chronic MI that were newly detected during the survey and those not under treatment at the time of the study were referred for treatment to the nearest available facilities.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of the collected data was simultaneously undertaken using the SPSS package and preliminary tables generated were used as baseline data on nature of stigma and discrimination experienced by the members in the groups and the views on methods to reduce stigma and discrimination. Further data was analyzed using Z-test.

Phase II

An intervention package was prepared based on the results of the initial assessment. All material was prepared in the local language that is, Kannada and were field tested. Where ever necessary, modifications were made. The package consisted of:

Psycho-education

Exhibition (posters)

Question answer sessions

Distribution of printed material

Street plays.

Street play was conceptualized and scripted by the project staff, faculty of RF PG College and a theatre director. Children from a local school were trained to enact the play. The street play depicted the following:

Suffering caused due to MI

Symptoms and causes of MI

Myths of MI

Need for a supportive environment and empathic understanding

Importance of treatment and treatment adherence

Ill effect of ridiculing, ignoring, differentiation and discrimination

Possibility of recovery from MI and occupation

Possibility of carrying on with the day to day activities and responsibilities.

The messages in all the material focused on:

Causes of MI

Common myths and stigma of MI in the community

Consequences of stigma

Treatment of MI

Facilities available for treatment

Phase III

Intervention was carried out in centrally located places. All interventional sessions were followed by interactive “question and answer” sessions. About 1300 persons who had participated in the initial assessment participated in the intervention programs. Intervention consisted of ten psycho-education session in groups of 80-120 persons through slide shows and discussions; 10 exhibitions through posters and explanations, 10 shows of street play were enacted; and printed educational materials were distributed.

Phase IV

Two post intervention assessments (PIAs) were carried out. First assessment was done within a month of the intervention, and the second assessment was done 3 months after the intervention. PIA was done by interviewers other than those who had done the basline assessment.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of the collected data was carried out using the SPSS package to find out the impact of the intervention, by comparing the baseline assessment with the PIA, and the sustainability of the change, if any, for the duration of 3 months by comparing the two PIAs.

RESULTS

Sample description

Community group

Nine hundred and one household was surveyed for eliciting information on stigma in the community. Majority (62.5%) were between the ages of 30 and 59 years while 27.1% were below 29 years, and 10.4% were over 59 years. Men constituted 46.6% of the sample and women were 53.4%. Of this group 96.7% were Hindus, 3.1% were Muslims and 0.2% were Christians reflecting caste wise population in that region. Literacy wise, 40.1% were illiterates; 19.8% were educated up to primary or middle school, and 35.1% had higher secondary education while 5.1% had collegiate education.

Caregiver group

In this group 213 caregivers participated. Of them 83.5% were in the age range of 30-59 years. Men constituted 50.2% while women were 49.8%. Of the caregivers 27.23% were spouses, 44.14% represented parents, 20.18% were siblings and 8.45% were other relatives of the patients. Among this group 94.4% of the members were Hindus and 5.6% were Muslims.

Mentally ill persons

Two hundred and twenty-three cases were identified. Diagnostic categories were Schizophrenia, Bipolar Affective Disorder, Major Depression, and Chronic Anxiety Disorder. All had the illness for a period between 5 years and 27 years, fulfilling the criteria for chronicity. Men constituted 54.3%, and women constituted 45.7% of the group. In this group 39.6% were below 20 years of age, 17.6% were between 20 years and 29 years and 20.7% were between 30 years and 39 years, and 16.7% were between 40 years and 49 years of age. 41.7% of this group was married, and 58.3% were unmarried. Of the married 34.7% were men, and 50% were women. 76.2% of the ill persons had taken some treatment at some point of time. 12.6% consulted religious priests; 9.9% consulted general doctors/physicians, 4% sought help from “Dais,” 20.4% consulted doctors in hospitals, 52.9% sought treatment from mental health professionals.

Nature of stigma

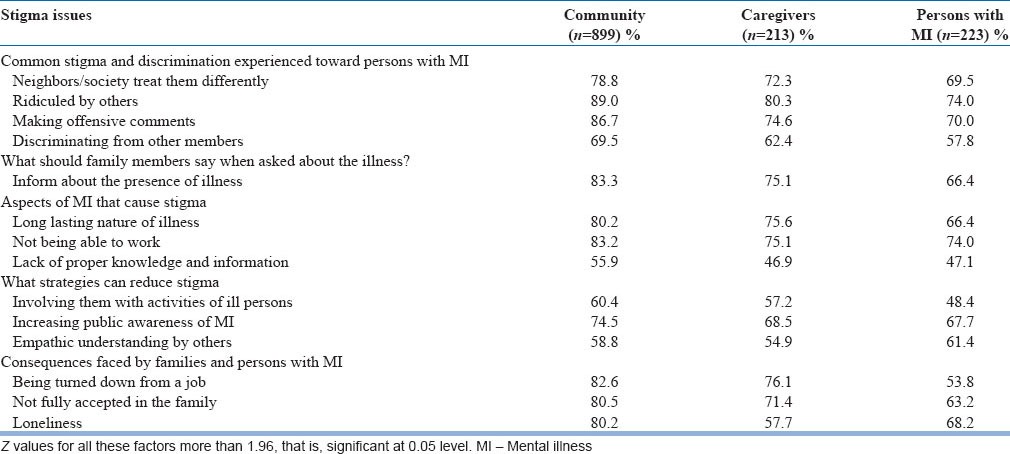

Results of this study on stigma are summarized in Tables 1-3. The baseline assessment revealed following factors contributing to stigma:

Table 1.

Responses on stigma scale at baseline of the three groups

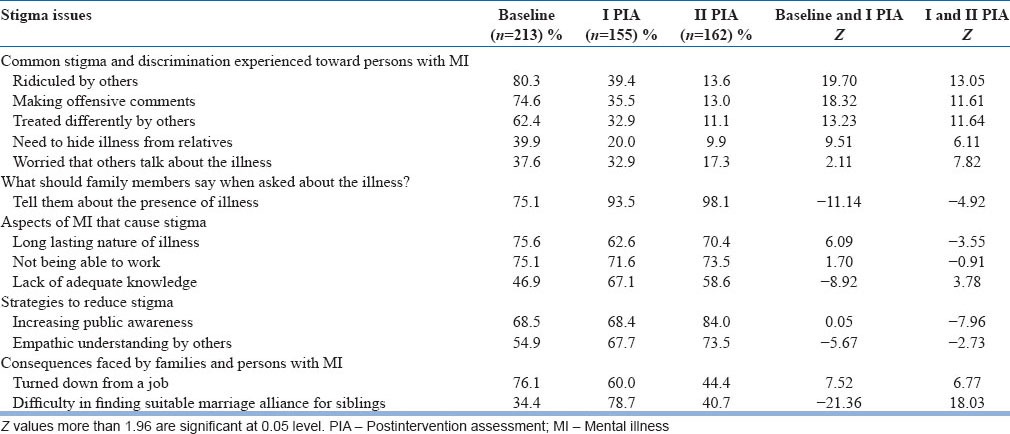

Table 3.

Comparison of responses of caregivers during baseline and two PIAs

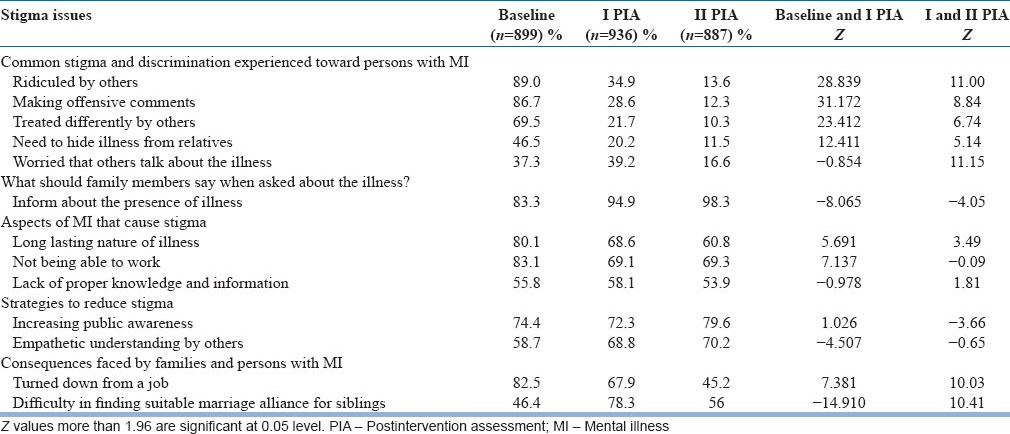

Table 2.

Comparison of responses of community during baseline and PIAs

Being ridiculed by others

Offensive comments by others

Neighbours/society's differential treatment

Discrimination

Need to hide the illness.

Common reasons of stigma as perceived by the respondents were:

Not being able to work

Long lasting nature of the illness

Lack of correct and complete knowledge about the illness.

Some of the important consequences of stigma perceived by family members were:

Being turned down from a job in-spite of being qualified

Not being fully accepted into the family

Loneliness.

Disclosure of MI is a contentious issue due to fear of being ridiculed, discrimination, loss of job or not being able to get a job, and difficulty in getting married. Hence, concerned people deal with it by hiding the illness or not disclosing the presence of illness.

These results are similar to those reported in other studies.[5,16]

Comparing the baseline responses of community with that of the caregivers using Z values, significant differences were found on almost all the items indicating that caregivers had significantly less perceived stigma than the community (P < 0.05).

Postintervention changes

Postintervention assessment showed significant reduction in percentage of respondents expressing stigmatizing views in both caregivers and community groups. However, people maintained concern about others talking about the illness and concern about disclosure. The belief, that lack of knowledge and attribution of unnatural causes to MI resulting in stigma did not change. Likewise, there was no change in the opinion that stigma can only be partially removed.

A significant drop in the number of respondents endorsing stigmatizing views was found during the second PIA. Pattern of responses remained the same as far as the disclosure, aspect of MI that cause stigma, possibility of reducing stigma and effective strategies to reduce stigma were concerned. After the intervention program significant number of respondents expressed the need for medical support in the community (82.9%) as well as the caregivers (91.6%) as compared to pre intervention figures of 73.3% and 69% respectively (P < 0.05 level).

An attempt was made to find gender differences if any in this group since gender differences have been reported in earlier studies.[17,18,19] Among the persons with MI, there were 42 married men and 51 married women. 54% of the married women were not living with their spouses but were living with their parents after the onset of the illness. Among married men, only 17% were not living with their spouses. Women were sent back to their parents’ home by their husbands/parents-in-law as they felt they would not be able to look after their wives/daughter-in-laws. Hence, the women were taken care of by their parents and/or siblings whereas most of the married mentally ill men were taken care of by their wives. This again supports the earlier findings that in the Indian context married mentally ill women end up taking shelter with their family of origin, once they get rejected by the husbands and at the same time, mentally ill men continue to be taken care of by their wives. Hiding MI, getting married, discontinuing treatment resulting in a relapse could be associated with separation.

DISCUSSION

Stigma as a result of MI has its negative consequences which reflect poor attitude and adverse behavior of the community toward the ill person. Changing beliefs, attitudes and behavior is a complex and difficult task and changes as a phenomena or process takes its own course. Smith[20] opines that generalizing the results of anti-stigma research and generating meaningful outcome measures from short term interventions has its limitations but attempts to start such interventions should be encouraged. In a review of the literature on stigma and disability in schizophrenia the authors note that there is dearth of evidence based interventions to reduce stigma and models of interventions need to be developed and tested.[21] The present study has made an attempt to understand the presence of stigma and evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention package developed for the purpose of reducing stigma.

As far as the nature of stigma is concerned the present study has demonstrated results similar to those reported in the literature. Surprisingly presence of socially unacceptable behavior was not seen as a reason for the stigma by majority of the respondents. It is reported that rural community is more tolerant of disturbed behavior, and this could be an explanation for this finding.[22] Moreover, socially unacceptable behavior is characteristics of acute phase of illness lasting for a short period (after starting treatment) hence may not influence the attitudes and associated stigma.[7,23] The study also supports the view that promoting contact with mentally ill persons, leads to attitudinal change.[8,24,25,26] Supporting these reports, in the present study caregivers, who are in constant contact with the ill person, had less stigmatizing views about MI compared to persons in the community.

Stigma researches in India suggest and recommend educational programs for public about MI to dispel the myths, organizing mental health services, and changing media presentation of mental disorders to reduce stigma.[15] It is also suggested that the educational programs should provide both biological and psychosocial explanations in order to counter such attitudes.[27,28,29]

Considering these suggestions and the pre intervention findings on the nature of stigma, the present study provided information about MI with both biological as well as psychosocial components in the intervention package. The program brought about a significant reduction in the negative and stigmatizing views of the respondents. The changes that were seen during the first PIA were maintained during the second PIA, that is, after 3 months of intervention. In line with another reported study concern for marriage of the ill person and other siblings remained unchanged. Another important finding was that following the intervention more respondents expressed the need for medical support. Among the patients identified during the first phase, 70.85% had discontinued medical treatment or had not sought psychiatric treatment at all in the first place. Some of the reasons given for this were financial constraints, poor accessibility of services, and lack of information about the illness and available treatment, shame and apprehension, and lack of sensitivity among family members. Many expressed the fact that a person “had actually recovered” and hence did not need treatment anymore. Recurrence of symptoms was interpreted as uselessness of the medical treatment. The “stigma reduction interventional package” had a beneficial influence on this, and they expressed the need for treatment and also willingness to seek help, following their participation in the intervention program. Seeking medical help has important implications. Firstly the obvious and threatening symptoms can be controlled/reduced and this in turn would diminish one of the sources of stigma, that is, sense of threat to observers. Secondly, this increases a sense of control and effectiveness on the part of the treated individual. This in turn would improve social interaction thereby promoting reduction in stigmatization. Thirdly, the individual may be relieved of personal suffering and would be able to face the challenges better. Fourthly, persons, who see the benefits of successful treatment, would realize that such a change is possible and that people with MI can actually overcome adversities.[2]

CONCLUSION

The present study demonstrates the effectiveness of suitably structured education program on the stigmatizing views of a rural and semi-urban community with respect to MI. The study also establishes that these changes could be sustained for a period of 3 months when PIAs were carried out. Further, follow up studies will probably reveal as to how long such a change will sustain. However, from this and earlier studies it is clear that sustained efforts need to be made to bring about a change and reduce stigma of MI. The results also suggest that easily accessible low-cost mental health services need to be organized in the community that should also address the issue of cost of accessing the services. Educational and awareness programs should be a part of these services that need be planned on a long term and continuing basis.

The study has its limitations. Firstly, it is a cross sectional study. A longitudinal study can help to understand the change process especially the sustenance of change effected by awareness programs. Secondly, this study is confined to a specific rural and semi-urban area. An urban setting may perhaps require a different strategy. Thirdly, being a community study it was not possible to have a control group of participants who did not attend the intervention program, for the purposes of comparison.[2]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study team acknowledges the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India for providing the necessary funds for undertaking the present study under the National Mental Health Program (2006-2008). We would like to thank all who have contributed to the study at different phases of the program. Thanks are due to Mr. Upendra and the students of the Quite Corner English School, Chikballapur, Karnataka, for their contribution in directing and enacting the street play.

Appendix: I Semi Structured Interview Schedule

Socio-demographic information respondent details

Name: __________________________________________

Age:

-

Gender

- Male

- Female

State: ________________________________________

-

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

- Illiterate

- Elementary or up to and including grade 5

- Diploma/College

- University

-

What is your current marital status?

- Married

- Separated

- Divorced

- Widowed

- Single, i.e., never married

- Not applicable

-

What is your employment status?

- Employed full-time

- Employed part-time

- Self-employed

- Unemployed

- Retired

- Student

- Homemaker

-

What is your religious affiliation?

- Hindu

- Muslim

- Christian

- Other

Asset Index was used to find the economic status.

-

Residence

- Rural

- Urban

Family size

-

Family type

- Single

- Joint

- Nuclear

- Living together

-

Clinical diagnosis of the patient (specify):

____________________________________

-

Duration of illness

- 6 months-1 year

- 1-2 years

- >2 years

- Not available

Stigma and discrimination faced by patient

-

Have you/your relative faced stigma and discrimination due to the illness? (Record verbatim)

If there is no response to the above question, enquire about:

- Has your life changed after you have had the illness?

- Are there things that you experience which others without the illness do not?

- Do you have to hide your illness?

- Many people with similar illness experience shame, ridicule, and discrimination; have you also experienced these?

-

Yes 2. No

If no, skip question no. 2.

-

If yes, at what stage of the illness was the stigma and discrimination most felt?

(Record verbatim response)

-

Common stigma and discrimination experienced by the patient

- Neighbors/society treat differently

- Ridiculing by others

- Making offensive comments

- Discrimination by family members

- Worried that neighbors would avoid

- Physical abuse (kicking, beating)

- Need to hide from relatives

- Worried about talking about illness

- Ashamed or embarrassed about it

- Worried that I would be blamed for illness

- Difficulty in getting marriage proposals

- Any other

- Not applicable

-

Attitudes of relatives towards you (tick off the relevant responses):

- Acceptance

- Help with medical support

- Rejection

- Avoidance

- Loss of respect for the family

- Any other

-

What about visiting, and visits of, friends and relatives?

- Visit as usual

- Visit less frequently

- Do not know/not applicable

- Don’t visit at all

- Any other

-

When people ask you what is wrong with you, what do you tell them?

(One reply only)

- I am mentally ill.

- General weakness, bodily aches, and pains

- Headache and discomfort in head

- Not feeling well

- Boredom

- Avoid telling about mental illness

- Tension/Depression

- Other response

-

How do people react if they come to know that you have got mental illness?

- No change in reaction

- Call me mad

- Talking badly and teasing

- Discrimination

- Appreciation over improvement

- Curiosity

- Show pity

- Any other

-

In your opinion what aspect of illness creates stigma?

(One answer only)

- Long-lasting nature of illness

- Not being able to work

- Lack of correct knowledge

- Presence of socially unacceptable behavior

- Attribution of supernatural causation

- Any other

-

a) Do you think the stigma you suffer can be removed?

If yes, to what extent?

- Entirely removed

- Partially removed

- Not possible to remove

- Cannot say

- Any other

b) What are the common strategies that you use or can be applied to fight the stigma and discrimination? (Record all responses) (Yes/No/Don’t know)

- Involvement in advocacy activities

- Immediate challenge of the stigmatizing remark

- Concealment or selective disclosure of illness

- Involvement with other consumers

- Increasing public awareness to reduce the stigma

- Empathic understanding by others

- Giving another diagnosis

- Any other

-

What are the consequences you have experienced because of the stigma and discrimination?

- Avoid disclosing the mental illness histories in jobs/applications

- Had been turned down for a job in spite of being qualified

- Not fully accepted in the family

- Living alone

- Pushed into unacceptable social situation

- Sexual harassment

- Social exploitation

- Difficulty in renting house

- Difficulty in finding suitable match for the sibling

- Difficulty in getting admission to school/college

- Had to experience poor sexual relationship

- Any other

-

Have you been divorced or separated as a result of stigma towards your illness?

- Yes

- No

-

Nature of stigma experienced: (Write all relevant responses)

- Personal area

- Occupational area

- Social area

- Marital life

- Family life

- Any other

- Not applicable

-

Which of the following do you feel would be most disabling?

(One answer only)

- Loss of arms or legs

- Loss of vision/hearing

- Being permanently bedridden

- Mental illness

- Any other

Any other information you would like to share about this topic?

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Alboleda-Florez J. Rights of a powerless legion. In: Arboleda-Florez J, Sartorius N, editors. Understanding the Stigma of Mental Illness: Theory and Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley; 2008. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinshaw SP. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. Mark of Shame: Stigma of Mental Illness and an Agenda for Change. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geneva: WHO and APA; 2002. World Health Organization and American Psychiatric Association. Reducing Stigma and Discrimination Against Older People with Mental Disorders: A Technical Consensus Statement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrigan PW, Kleinhen P. The impact of mental illness stigma. In: Corrigan PW, editor. On the Stigma of Mental Illness: Practical Strategies for Research and Social Change. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thara R, Srinivasan TN. How stigmatising is schizophrenia in India? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:135–41. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1775–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raguram R, Raghu TM, Vounatsou P, Weiss MG. Schizophrenia and the cultural epidemiology of stigma in Bangalore, India. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:734–44. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000144692.24993.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Penn DL, Uphoff-Wasowski K, Campion J, et al. Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:187–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes EP, Corrigan PW, Williams P, Canar J, Kubiak MA. Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:447–56. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartorius N, Schulze H. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. Reducing the Stigma of Mental Illness: A Report. [Google Scholar]

- 11.New York: World Psychiatric Association; 1998. World Psychiatric Association. Fighting Stigma and Discrimination because of Schizophrenia. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estroff SE, Penn DL, Toporek JR. From stigma to discrimination: An analysis of community efforts to reduce the negative consequences of having a psychiatric disorder and label. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:493–509. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2007. International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International. National Family Health. Survey (NFHS-3):2005-06, India. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Census 2001 Report. Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murthy SR. Perspectives on stigma of mental illness. In: Okasha A, Stefanis CN, editors. Stigma of Mental Illness in the Third World. World Psychiatric Association; 2005. pp. 112–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thara R, Kamath S, Kumar S. Women with schizophrenia and broken marriages – doubly disadvantaged? Part I: Patient perspective. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2003;49:225–32. doi: 10.1177/00207640030493008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thara R, Kamath S, Kumar S. Women with schizophrenia and broken marriages – doubly disadvantaged? Part II: Family perspective. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2003;49:233–40. doi: 10.1177/00207640030493009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skultans V. Women and affliction in Maharashtra: A hydraulic model of health and illness. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1991;15:321–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00046542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith M. Stigma. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2002;8:317–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thirthalli J, Kumar CN. Stigma and disability in schizophrenia: Developing countries’ perspective. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24:423–40. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.703644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neki JS. Problems of motivation affecting the psychiatrist, general practitioner and the public in their interaction in the field of mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 1966;8:117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penn DL, Guynan K, Daily T, Spaulding WD, Garbin CP, Sullivan M. Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: What sort of information is best? Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:567–78. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:963–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans-Lacko S, Brohan E, Mojtabai R, Thornicroft G. Association between public views of mental illness and self-stigma among individuals with mental illness in 14 European countries. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1741–52. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans-Lacko S, London J, Japhet S, Rüsch N, Flach C, Corker E, et al. Mass social contact interventions and their effect on mental health related stigma and intended discrimination. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:489. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta SI, Farina A. Is being “sick” really better? Effect of the disease view of mental disorder on stigma. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1997;16:405–19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Read J, Law A. The relationship of causal beliefs and contact with users of mental health services to attitudes to the ‘mentally ill’. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1999;45:216–29. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]