Abstract

Background:

Wide prevalence of mental illness has been documented in South India; however, the magnitude of stigma is unclear.

Aims:

The aim was to investigate the magnitude of stigma prevalent among medical professionals in Hyderabad, India.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective survey of seven common psychiatric disorders for eight specified perceptions was conducted. Responses of 226 out of 250 (90%) doctors were analyzed.

Results:

Significant overall negative perception (P < 0.001), with drug addiction (52.8%) and alcoholism (48.2%) eliciting most negative perceptions (Chi-square: P <0.05) was observed. Significant negative perceptions were also seen among married doctors and those with < 10 years experience. Even though, there was no overall difference based on gender (P = 0.242), more females had significant negative perception toward eating disorders, depression, dementia, alcoholism and schizophrenic patients (P ≤ 0.05).

Conclusions:

This study revealed negative attitude of doctors toward mentally ill and highlighted the gender difference in perceptions.

Keywords: Attitudes, doctors, Hyderabad, India, mental illness

INTRODUCTION

World Health Organization defines health as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Mental wellbeing has been emphasized for ages, yet to this day mental health professionals encounter stigma in their daily practice that hinders the recovery process and reduces the quality of life of their patients.[1] Profound negative attitudes toward psychiatric illness were documented in the early studies.[2] The stigma associated with mental illness is well-recognized in the West. However, there is insufficient data about stigma in developing countries.[3] Previous research studies conducted in India revealed that psychiatry is still an evolving specialty.[4] Kapur described that in India religious beliefs and traditional medicine played a major role in the treatment seeking pattern of patients and that patients from rural areas were initially seen by religious healers and patients would get to urban-based psychiatrists only if symptoms hadn’t resolved. It has been observed that symptoms of mental illness are always interpreted along religious lines and stigma is prevalent.[5] Literature on stigma in India revealed that rural Indians showed greater stigma compared to urban dwellers. Urban group showed a strong link between stigma and not wishing to work with a mentally ill individual.[6] Further urban patient population felt the need to hide their illness and avoided illness histories in job applications, whereas rural patient population experienced more ridicule, shame and discrimination.[7] In developing countries like India, the above evidence shows that stigma associated with mental illness has risen. Research demonstrated that South India is the suicide capital of India.[8] Hyderabad is one of the larger cities in South India and is the capital and economic hub of its state, Andhra Pradesh. There is no data available on stigma towards mentally ill in this region. The only significant data available pertaining to psychiatric illness and the psychiatrically ill was on suicide and help seeking attitude of mentally ill. Research on suicide rate in other South Indian states such as Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh showed that the suicide rate was >15% when compared to <3% in the Northern states of India. This high suicide rate in south India was attributed, among other factors, to modernization and result of only small percentage of people with mental illness seeking medical help.[9] Case–control studies in two major cities in South India, Chennai and Bangalore revealed that among those who died by suicide, 88% in Chennai and 43% in Bangalore had diagnosable mental disorders. However, only 10% ever visited a mental health professional.[10,11] Since not enough data is available on stigma and suicides in Hyderabad, and hypothesizing that stigma is the reason for majority of mentally ill refraining from seeking help, this city was chosen to evaluate the magnitude of stigma prevalent in medical professionals. This study proposed to evaluate if stigma was prevalent among doctors and if gender differences contribute to stigma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 250 private medical practitioners in Hyderabad, India were approached for the survey. This sample population was chosen as they are proficient in English language and have familiarity with the common psychiatric disorders.

Measures

The questionnaire used in this survey was the same used by similar studies (including assessing attitudes of doctors) done in United Kingdom and Pakistan.[3,12,13] This questionnaire was preferred since it is less intrusive of the doctors’ schedule, and it minimizes observer bias. Furthermore, the features of medical training, medical textbooks followed in India are the same as those followed in UK that supports the decision of using the same survey form for a sample.[3,14] Only demographic questions were changed according to the sample and purpose of the study tested. The only contrast is that in addition we included questions to assess the use of strategies by doctors to tackle stigma.

In brief, the first part of the questionnaire comprised of questions on demographic variables. Second part of the questionnaire contained questions about the seven common psychiatric disorders: Schizophrenia, panic attacks, eating disorders, drug addiction, depression, dementia, and alcoholism. The perceptions toward eight aspects (derived from the work of Hayward and Bright[13]): Danger to others, unpredictability, ability to pull themselves together, regarding themselves different from others, being difficult to talk to, inability to respond to treatment, and recovery were evaluated. Responses were recorded on a five-point scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree and Strongly Disagree). Questions testing awareness and use of strategies by the sample population comprised the last part of the questionnaire.

Procedure

The questionnaires were distributed along with a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, by hand or via E-mail and returned either by prepaid envelopes or by E-mail. Male and female doctors were contacted alternately to ensure the equal number of male and female participants. 4 weeks time was given for completion of questionnaires. A reminder was sent to the participants who didn’t return completed questionnaires after 3 weeks. The study was approved by the Texas A and M University of Kingsville Institutional Review Board.

All collected questionnaires were anonymized by a randomly generated four-digit ID, which served as a means of cataloging each questionnaire. Data gathered were divided into groups according to age, gender, marital status, specialty, knowledge of someone with a psychiatric disorder and experience in order to see the difference in attitude between medical professionals of varied demographics. Comparison of data between male and female responders was also done to assess for any influence of gender on stigma. Data on strategies used to reduce stigma was also interpreted.

Statistical considerations

The variables in the study were mostly categorical. Parametric analyses were carried out for measuring normally distributed data such as age and years of experience. Crosstabs were used for comparing nonparametric calculations. Chi-square test and Z-test were used for significance testing of overall negative opinion, negative opinion and influence of gender and assessment of variation in negative opinion between demographic variables. A P ≤ 0.05 was considered as significant. Analyses were carried out using SPSS 18.0.

RESULTS

Out of 250 doctors contacted, 8 doctors refused to be interviewed, and 16 doctors did not return the questionnaires. 226 participants (90%) returned the completed questionnaires. Of the responders, 50% were males, 50% were married and >70% specialized in Medicine and had <10 years of experience.

Overall negative perceptions

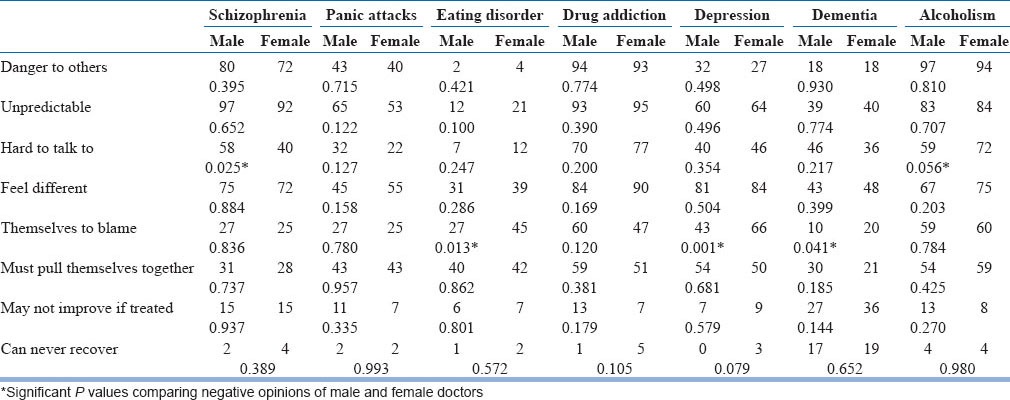

The overall proportion of male and female respondents with negative perceptions is outlined in Table 1. Participants were regarded as having a negative opinion if they indicated “Strongly Agree” or “Agree” for aspects outlined for each disorder in the questionnaire. There was a significant overall negative perception (Chi-square: P <0.001) toward all the disorders surveyed when compared with positive perception. Drug addiction (52.8%) and alcoholism (48.2%) elicited significant negative perceptions (Chi-square test: P <0.05). Similar proportion of respondents (83%) rated people with alcoholism and drug addiction as danger to others. 83% and 74% of respondents rated people with drug addiction and alcoholism respectively as unpredictable.

Table 1.

Attitudes to mental illness by type of illness: Proportion of respondents having negative perceptions and influence of gender

After drug addiction and alcoholism, schizophrenia (40.6%) and depression (36.8%) had most negative perception. For patients with schizophrenia, respondents felt that they are a danger to others (67%), unpredictable (84%) and feel different (65%) though very few respondents felt they may not improve with treatment (13.27%) and only 2% felt they can never recover. For depression, most respondents felt (73%) that they feel different and are unpredictable (55%). 48% of respondents felt depressed patients are themselves to blame and 46% opined that they must pull themselves together.

Eating disorders elicited the least negative perception (17.2%). Though eating disorders received less negative opinion, 36% of respondents thought that people with eating disorders are capable of helping themselves, and 32% responded that they had only themselves to blame.

There was a widespread response that people with alcoholism, drug addiction, and schizophrenia were hard to talk to (less so for those with eating disorders and panic attacks). Responses about treatment and recovery showed that most respondents were optimistic about recovery with treatment for most disorders with the exception of dementia.

Influence of gender

Responses to questions about each aspect of all the seven disorders differed between male and female respondents [Table 1]. Male doctors held an opinion that people with schizophrenia were hard to talk to. Significantly more female doctors thought that patients were themselves to blame for depression (P < 0.001), dementia (P = 0.04) and eating disorders (P = 0.01) and were hard to talk to for schizophrenia (P = 0.03) and alcoholism (P = 0.05). However, there was no overall significant difference in the negative opinions based on gender (P = 0.242).

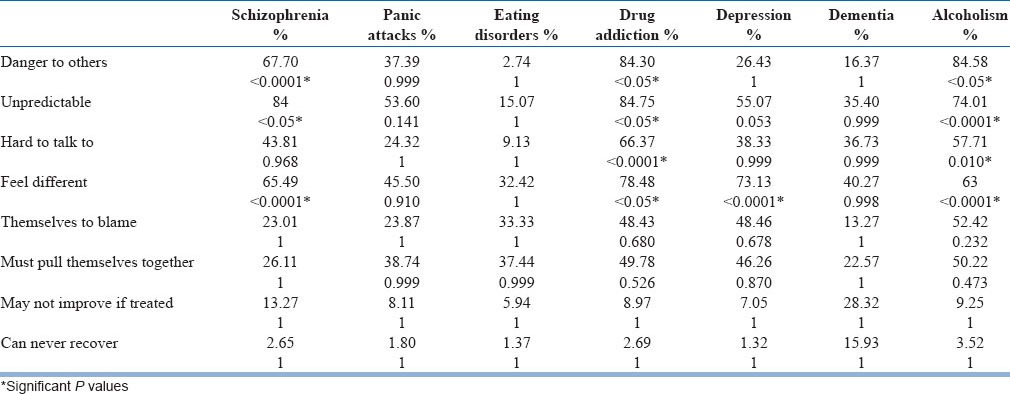

Negative perception based on disease type

Respondents had significant negative perceptions towards patients with schizophrenia, drug addiction, depression and alcoholism (Z-test). Significant negative perceptions were found toward aspects of dangerousness (P < 0.0001), and unpredictability (P < 0.05) aspects of schizophrenia. Respondents also thought that people with schizophrenia regarded themselves as different from others (P < 0.0001). Drug addiction, on the other hand, had a significant negative perception to the following aspects: Aspects of dangerousness (P < 0.05), unpredictability (P < 0.05), hard to talk to (P < 0.0001), and being different from others (P < 0.05). Findings also suggest that respondents had significant negative perception for aspects of unpredictability (P < 0.053), and being different from others (P < 0.0001) for patients with depression. Finally, alcoholism had significant negative perception toward dangerousness (P < 0.05) and unpredictability (P < 0.0001). Respondents thought that such people are hard to talk with (P < 0.010), and regard themselves different from others (P < 0.0001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Z-test on attitudes of doctors toward mental illness based on disease type

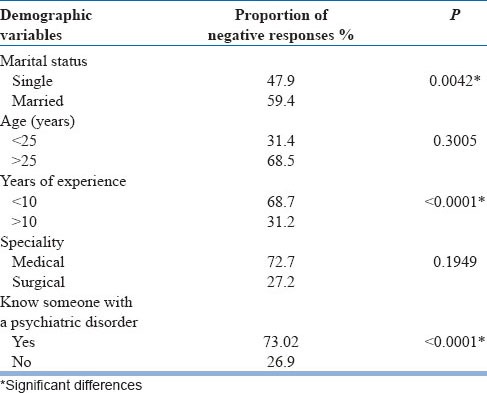

Influence of other demographic variables

Perception of respondents influenced by various demographic variables revealed significant negative perception among doctors who were married (when compared with doctors who were single), doctors with <10 years of experience (when compared with doctors with >10 years of experience) and doctors who knew someone with a psychiatric disorder (when compared to doctors who did not know someone with a psychiatric disorder). No significant difference was noted in the negative perception between those who practice medicine and those who practice surgery and between those who were younger than 25 years and those who were older than 25 years [Table 3].

Table 3.

Chi-square analysis comparing negative perceptions among different demographic variables

Strategies

Only 6% of participants responded to the questions about knowledge of strategies employed by state or mental health organizations to tackle stigma toward mentally ill. Most respondents did not have any knowledge of strategies used partly because of lack of awareness or because of their clinical practice in a different specialty other than psychiatry. Due to the small number of responses and their varied nature, the responses were not conducive to be analyzed.

DISCUSSION

Research has shown that stigma towards mental illness and mentally ill is a significant concern.[1] It is imperative that the impact of stigma and ways to prevent and reduce it should be further explored and developed. The present study has determined the perceptions of doctors in Hyderabad, India about mentally ill, with a specific focus on perceptions about seven different psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, gender differences in perceptions were assessed. The results showed that the negative attitude toward people with psychiatric disorders is widely held by doctors in Hyderabad though it varied with disorder type. Out of the seven disorders evaluated, only schizophrenia, eating disorders, drug addiction and alcoholism reflected a certain degree of stigmatizing perceptions. The role of gender in determining a person's stigmatizing views on mental illnesses was minimal due to the small number of aspects of each disorder that had significant differences between both genders. Female doctors held more stigmatizing opinions toward patients with eating disorders, depression, dementia, alcoholism and drug addiction.

Similar studies done in Pakistan, and the U.K showed significant negative perceptions towards dangerousness aspect of schizophrenia, and greater proportion of negative opinion was elicited by drug addiction, alcoholism and schizophrenia.[3,12] These coincide with the present findings except that in this study significant negative opinion was also obtained for “being different from others aspect” of depression. Evidently, there was awareness of various disorders and understanding of symptoms, and not all mental illnesses were considered stigmatizing by the sample population. This is depicted by conclusion of responses to various aspects tested. Stigmatizing perceptions on schizophrenia were mainly based on manifestations of the disease especially dangerousness, yet the significant negative opinion was taken into consideration since dangerousness depends on the type of schizophrenia. With regards to depression significance of aspect of being different from others was considered, attributing it to self-stigmatization. Alcoholism and drug addiction elicited the greatest level of stigma because these patients are primarily responsible for their actions.

Significant cumulative negative opinion towards all psychiatric disorders was present when compared to the positive opinion indicating the prevalence of stigma among doctors. However, there was no overall significant difference in the negative opinions based on gender. There was a significant negative perception of males toward “difficult to communicate with” aspect of schizophrenia when compared to females. On the other hand, females had more negative perception toward “themselves to blame” aspect of eating disorders, depression and dementia. Previous research revealed that there is no influence of gender on stigma[15] but this research was in the western countries and the observed gender difference may be attributed to the cultural differences in India compared to the West. Also, the opinions of female doctors may be due to the predominant prevalence of eating disorders and depression in females.[16]

When negative perceptions were compared with demographic variables, significant negative perception was observed among doctors who were married, who had <10 years of experience and among doctors who knew someone with a psychiatric disorder. Apart from the stigma, this can be attributed to the fact that larger proportion of the sample being between 23 and 30 years. The significant difference in opinion obtained with regards to knowledge of someone with a psychiatric disorder was similar to previous studies.[3] This opinion may have resulted from the understanding of the impact of mental illness on the patient's life.

Only 6% of participants responded to the questions regarding strategies and use of strategies to reduce stigma faced by mentally ill patients. This can be explained by lack of awareness and inability to harness local resources, strategies available to reduce stigma, lack of initiative among the doctors to tackle stigma and busy schedule. Most practitioners, other than psychiatrists, refused to respond to those as they were impertinent to their specialty. Apart from a lack of knowledge of stigma and ways to reduce it among those who were contacted, fewer psychiatrists in private practice, use of open-ended questions for assessing knowledge on strategies contributed to fewer responses. Most psychiatrists were employed with Government and private institutions rather than practicing individually like most practitioners of other specialties. Nonetheless, results obtained from the survey imply that appropriate measures should be implemented to tackle stigma in Hyderabad.

Though significant overall negative opinion was prevalent in the sample, a general or collective conclusion of the perception of doctors toward the mentally ill could not be directly solicited from this study. This is due to the fact that the seven disorders/symptoms reflective of mental illnesses evaluated in the study varied in different parameters such as nature, causes, effects, manifestations, etc., Since views held against patients with such mental illnesses were extensively based on these parameters, a general overview of mental illness as a construct associated with stigma could not be procured.

The findings of this study are limited in their scope to medical practitioners in Hyderabad, India, and they may not be generalized to medical practitioners throughout India. Only doctors were included, and opinions of other health professionals, and social workers were not included. Use of closed-ended questions for gathering data regarding strategies may have given a conclusive idea of knowledge and the use of strategies by the sample population.

This study is unique in being the first to evaluate stigma of mental illness in Hyderabad and to outline the gender differences in perception. Negative attitude towards people with psychiatric disorders is widely held by doctors in Hyderabad. These attitudes varied across the mental disorders in question. However, it was evident that not all mental illnesses were considered as stigmatizing by doctors in Hyderabad. Out of the seven disorders evaluated, only schizophrenia, eating disorders, drug addiction and alcoholism reflected a certain degree of stigmatizing perceptions. The role of gender in determining a person's stigmatizing views on mental illnesses was minimal due to the small number of aspects of each disorder that had significant differences between both genders. However, female doctors had significant stigmatizing perceptions against patients with eating disorders when compared to that of male doctors.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:467–78. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabkin J. Public attitudes toward mental illness: A review of the literature. Schizophr Bull. 1974:9–33. doi: 10.1093/schbul/1.10.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naeem F, Ayub M, Javed Z, Irfan M, Haral F, Kingdon D. Stigma and psychiatric illness. A survey of attitude of medical students and doctors in Lahore, Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2006;18:46–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trivedi JK. Importance of undergraduate psychiatric training. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:101–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapur RL. Mental health care in rural India: A study of existing patterns and their implications for future policy. Br J Psychiatry. 1975;127:286–93. doi: 10.1192/bjp.127.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jadhav S, Littlewood R, Ryder AG, Chakraborty A, Jain S, Barua M. Stigmatization of severe mental illness in India: Against the simple industrialization hypothesis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:189–94. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soman CR, Safraj S, Kutty VR, Vijayakumar K, Ajayan K. Suicide in South India: A community-based study in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:261–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijaykumar L. Suicide and its prevention: The urgent need in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:81–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gururaj G, Isaac MK, Subbakrishna DK, Ranjani R. Risk factors for completed suicides: A case-control study from Bangalore, India. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004;11:183–91. doi: 10.1080/156609704/233/289706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijayakumar L, Rajkumar S. Are risk factors for suicide universal? A case-control study in India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:407–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:4–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayward P, Bright J. Stigma and mental illness: A review and critique. J Ment Health. 1997;6:345–54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukherjee R, Fialho A, Wijetunge K, et al. The stigmatisation of mental illness: The attitudes of medical students and doctors in a London teaching hospital. Psychiatr Bull. 2002;26:178–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrigan P, Thompson V, Lambert D, Sangster Y, Noel JG, Campbell J. Perceptions of discrimination among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1105–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wirth JH, Bodenhausen GV. The role of gender in mental-illness stigma: A national experiment. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:169–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]