Abstract

What happens if a King becomes mentally ill? Excerpts from the personal papers of Arthur Henry Cole, Resident to the Kingdom of Mysore in 1809, open up fascinating insights into the madness of rulers, in neighboring Coorg and faraway London, and ways in which different societies responded to this. Musings on legal capacity and restrictions imposed on account of insanity, as well as migration and ennui in imperial colonies inevitably follow.

Keywords: History of psychiatry, migration, colonial psychiatry, politics and psychiatry

Arthur Henry Cole, who has Cole's Park and Cole's road named after him in the fair and the salubrious city of Bengaluru, was a younger son of William Willoughby Cole, 1st Earl of Enniskillen, Ireland. He was educated at the Trinity College, Dublin and was appointed as a writer in the East India Company in 1801, at Madras, and then moved to Mysore. He worked under Sir Barry Close, the first Resident of Mysore, became an “in-charge” and finally the Resident to the Kingdom of Mysore in Bengaluru in 1809. The Trinity College library has some of his personal papers preserved in its collections.[1]

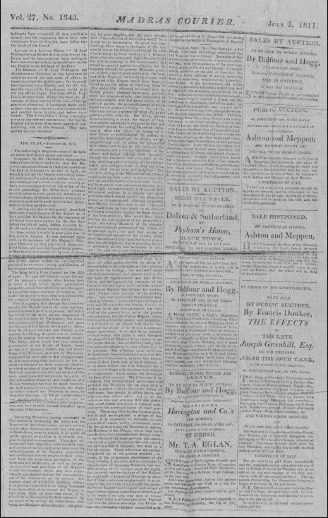

Tucked away in his personal papers, one finds a well-preserved copy of the Madras Courier (Volume 27, #1343, dated July 2, 1811) that talks about the madness of King George III, and its impact on the nature of governance. One also finds letters about the insanity of a local King (Dodda Veera Rajendra, Rajah of Coorg[2]), who had become pathologically jealous and suspicious. One can only speculate why Cole kept these two sets of documents, and perhaps wonder why the social and political consequences of insanity were so different in these two cases. Insanity and politics are often entwined, and one is tempted to draw lessons about both from history.

The various issues linked to the maladies of George III, most probably a bipolar disorder, have been discussed extensively over the years,[3] and featured in fiction, theatre, and movies. The King had developed his first major episode in 1789, but recovered sufficiently between episodes to function as the sovereign. He was replaced by the prince regent in 1811 and died in 1820. It was the process of disempowerment of the King while he was still alive and by a prince regent, which concerned the Madras Courier. “The Pilot” of January 30, 1811, which is excerpted in the Madras Courier, mentions that a constitutional crisis was brewing due to the “unfortunate” malady (insanity) that the King suffered from, who was now being “attended by physicians appointed for their skill to that unhappy malady, and supporting their authority by the ordinary attendants in such cases (…) a condition (in which he) could (not) have left 10 pounds by a will” (was legally of unsound mind).

THE “PILOT”

The “Pilot” protests that though the incapacity of the King had been discussed in the Parliament, and a Committee (the Lords Sidmouth, Liverpool, Eldon, and others) appointed to oversee matters of governance, and worried that when the “independent character and condition of a British sovereign (could) thus be made subservient with impunity to any faction of the state, or to the views of any Ministers or men, be they who they may be, the British Constitution (was) not merely shaken, it (was) dissolved, and the reign (was) given to every revolutionary projector, who may seek to raise himself hereafter upon the ruins of his country,” and that the situation makes “the sovereign a slave of his servants.”

This implies, in a sense, a belief that the King, whether sane or not, could not be deprived of his absolute power. The threat to the State posed by this questioning was larger than the threat raised by the debate between rationality and irrationality. The newspaper was also concerned about the restrictions placed upon the King and the machinations of the Ministers and other pretenders under a weak King. It was particularly critical of the fact that “notwithstanding all the outrages upon the rights, the character, and the feelings of the regent,” it (was) still suggested that he ought to keep those Ministers in office. They warn the Prince Regent that his concurrence was tantamount to high treason against himself, and compare it to the fate of Ferdinand who was deposed by Napoleon.

Despite these views, the parliamentary processes went on, and the King was divested of his executive role by the Regency Act (as mentioned above) on February 5, 1811. He was, however, not deprived, of either his liberty or position, and remained the King until his death in 1820. The Madras Courier was obviously unaware of all this even by July 1811, and clearly news did not travel as fast as it now does!

Why did Henry Cole retain this newspaper cutting? Just the previous year, in a letter to his sister, Florence, he describes certain events recounted by Mr. Ingledon, Esq., his physician, concerning a Rajah (King Veera Rajendra of Coorg) near Mysore, who had probably developed a paranoid disorder.

“In 1809, about the middle of November last, the Rajah having found out a formidable conspiracy that was against his life, ordered 2000 men to be killed, without any trial, and all male children to have their heads bashed on rocks. On the 16th November, the Rajah ordered a certain number to be slain (for what reason I cannot ascertain; only that his faculties must have been deranged at the time he issued the above inhuman order). The said Rajah has also become very suspicious and ordered many of his concubines to be executed (by bamboo tube being driven into the private parts of his concubine and molten lead poured in); while the eunuch who was found “fondling her” was ordered to be buggered to death” describes Mr. Ingledon.[4]

Madness and Kings

The two accounts, preserved in the same set of documents by Arthur Cole, regarding events in Coorg in 1809 and London in 1810, highlight the tension between madness and a sense of political order. The account in the Madras Courier emphasizes that the paramount power of the Regent cannot, and should not, be restricted by any other process, parliamentary or medical, as it was absolute, even though the King was insane. The suggestion that there should be parliamentary oversight was tantamount to treason. The ‘process in Britain disregarded’ this opinion, appropriate medical and social interventions were undertaken, and neither the State nor its people, had to suffer, unlike the thousands killed in Coorg. In the case of the Rajah, the same unquestioned obedience to absolute power had terrifying consequences because there were no processes in place to question the deranged mind of the ruler.

These issues of freedom and constraints as well as civic rights and responsibilities, as they apply to those with mental illness, continue to be debated even now.

These concerns two centuries ago have had profound consequences. A clause of sanity, being a prerequisite for rulers, has been inserted into most political and civil processes, so that those wielding political authority could only be the “sane.” The impact of this formalization of prejudice against the mentally ill is quite obvious, as the trickle-down effect gradually barred the mentally ill from any employment, civic role or even elementary processes like voting. Interestingly, a parallel narrative has been constructed around the widening of the ambit of “mental illness” to include a variety of conditions and behaviors, so that what we have now is a projection that one in four people may have had some sort of mental illness at some point of their lives.[5] The distinction between the “madness” of yesteryear and some “common mental disorders” of today has progressively become more blurred.

Colonial ennui

At another level, Arthur Cole's letters reveal a somewhat unhappy and lonely, even miserable, existence after moving to India. His letters to his sister, and to his mother, talked of the cultural issues linked to migration. Like many middle-class emigrants, his primary motive was to secure financial stability, and India was the preferred place to get rich quickly, especially for the younger sons of middle-level nobility. His initial exposure to Indian life in Calcutta in 1801 was more depressing than encouraging, and he described it as “living in a society (where there was) scarcely a person in which (he felt) the least relish for.” He wrote that “a kind of apathy” had a hold of him, and that he could not shake it off. He did, however, mention that he was “getting on as well as possible, and though (he) neither liked the country or the people” he spent his time pleasantly. He proceeded to pass an examination in Hindustanee in 1804 (a precursor to the-International English Language Testing System,[6] now essential for the journey in the other direction), at Fort William in Calcutta (the certificate is signed by Buchanan, the famous doctor who wrote on Mysore and Malabar) and moved to southern India, serving in Madras and Mysore. It was only when he moved to Mysore that he optimistically notes that his “prospects (were) much improved since (his) last (letter),” and that now he had “hopes.” However, the hopes kept receding, and by 1810, he was still concerned that his “return to England would be protracted for a century.” He wrote that “if in 10 years he could save 20,000 pounds (current value 62 million Pounds!)[7] it (would) do,” and that he was “not ambitious but want (ed) a modest fortune.” Despite all this, sleepy Mysore, got the better of him, and by 1811 he was forced to say that “everything in this country that you could feel interested in (went) on “humdrumically,” so that (he had) little to say.”

Photograph copyright Manuscripts and Archives Research Library (M and ARL), Trinity College, Dublin

It would be tempting to diagnose Arthur Cole as suffering from the “common mental disorder,” diagnosable as depression, based on the ennui and pessimism that marks his letters home. In the 19th century, migrating for economic betterment to a richer nation (the possibilities of acquiring a “modest” saving of 20,000 pounds was more likely in India than in Ireland) did not prevent Cole from feeling listless, bored, and unsure of how he fitted in. He also suffered from frequent bouts of headaches, weight loss, and colicky pains. Readers of this journal who have migrated from India to the “West” may have some empathy for Cole's predicament!

The movement of people during the phase of colonial expansion brought societies with very different traditions of dealing with madness, and psychological distress, face to face. The experience of madness, under feudal governance and attempts to restrict its effects by democratic processes, is still debated. Migration itself, whether from the seat of colonial power, or from one erstwhile colony (Ireland) to another (India), also created an interface wherein cultural dissonance could be seen to produce symptoms, even of what we might today call depression. The experiences of, and attitudes toward, severe mental illness and the common mental disorders are often said to have changed, but have they?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work is supported in part by a grant from The Wellcome Trust (WT096493MA) “Turning the Pages”.

The authors would also like to acknowledge the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library (M and ARL), Trinity College, Dublin, and the invitation extended to Sanjeev Jain that allowed this work to be done. We would also like to thank earlier anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The work is supported in part by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (WT096493MA)

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Dublin: Long Room Library, Trinity College; Cole Manuscripts; 3767/23-38; Manuscripts and Archives Research Library (M and ARL) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belliappa CP. India: Rupa Publications; 2013. Nuggets from Coorg History. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters TJ, Beveridge A. The blindness, deafness and madness of King George III: Psychiatric interactions. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40:81–5. doi: 10.4997/jrcpe.2010.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibid (1) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mental Disorders affect one in four people: WHO Press release. [Last downloaded on 2014 Dec 04]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2001/media_centre/press_release/en/

- 6. [Last downloaded on 2015 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_English_Language_Testing_System .

- 7. [Accessed 3 April 2015]. Available from: http://www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare/relativevalue.php .