Abstract

Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is a neurohormone that plays a crucial role in integrating the body’s overall response to stress. It appears necessary and sufficient for the organism to mount functional, physiological and endocrine responses to stressors. CRF is released in response to various triggers such as chronic stress. The role of CRF and its involvement in these neurological disorders suggest that new drugs that can target the CRF function or bind to its receptors may represent a new development of neuropsychiatric medicines to treat various stress-related disorders including depression, anxiety and addictive disorders. Based on pharmacophore of the CRF1 receptor antagonists, a new series of thiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidines were synthesized as Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor modulators and the prepared compounds carry groups shown to produce optimum binding affinity to CRF receptors. Twenty two compounds were evaluated for their CRF1 receptor binding affinity in HEK 293 cell lines and two compounds 5o and 5s showed approximately 25% binding affinity to CRF1 receptors. Selected compounds (5c and 5f) were also evaluated for their effect on expression of genes associated with depression and anxiety disorders such as CRF1, CREB, MAO-A, SERT, NPY, DatSLC6a3, and DBH and significant upregulation of CRF1 mRNA has been observed with compound 5c.

Keywords: Thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidines; corticotropin releasing factor; antalarmin; anxiety; depression.

INTRODUCTION

Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is a neurohormone that plays a crucial role in integrating the body’s overall response to stress. It appears necessary and sufficient for the organism to mount functional, physiological and endocrine responses to stressors. CRF is released in response to various triggers such as chronic stress. This then triggers the release of corticotropin (ACTH), another hormone, from the anterior pituitary gland which then triggers the secretion of the endogenous glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex that manages the physiological responses to stress [1, 2]. Chronic release of CRF and ACTH is believed to be directly or indirectly involved in many of the harmful physiological effects of chronic stress, such as excessive glucocorticoid release, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, stomach ulcers, anxiety, depression, development of high blood pressure and consequent cardiovascular problems [3].

Not surprisingly, many human psychopathologies which include hyper excitability or anxiety-like components are hypothesized to depend either casually or symptomatically on over-activation of CRF in the brain. Dysfunction in this system has been correlated with various diseases such as major depression [4], anxiety disorders [5] and eating disorders [6]. There is evidence that CRF may play a role in the stress-induced relapse of drug abuse and the anxiety-like behaviors observed during acute drug withdrawal and drug addiction [7, 8].

Administration of CRF provokes stress-like responses including simulation of the sympathetic nervous system [9, 10], inhibition of the parasympathetic nervous system with consequential increase in plasma concentration of adrenaline, noradrenaline and glucose, increase in heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure, inhibition of gastrointestinal function and acid secretion. The behavioral response to CRF administration in general is an increased arousal and emotional reactivity to the environment [2]. In addition to the neuromodulatory and neuroendocrine actions of CRF, it is also suggested that it may play a role in integrating the response of the immune system to physiological, psychological and immunological stressors [11]. Clinical data suggesting a role for CRF in major depression has been accumulating over the years. Early studies demonstrated that patients suffering from major depression disorders have elevated supra-normal concentration of CRF in their cerebrospinal fluid relative to normal volunteers [12]. Recently, there was a report of a preliminary clinical study where, in 20 depressed patients treated with a selective CRF1 receptor antagonist, a significant reduction in depression and anxiety scores was observed. Moreover, CRF levels are elevated in patients suffering from anorexia nervosa [13], obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic disorder. Several studies have provided evidence in support of alterations in CRF in Alzheimer’s disease [14]. Alterations in brain concentration of CRF have been reported in other neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease [15].

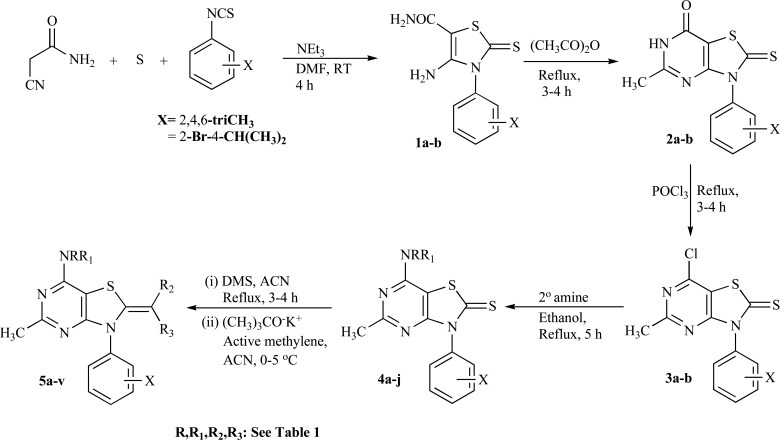

The role of CRF and its involvement in these neurological disorders and in behavioral, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, immune and reproductive systems suggests that new drugs that can target the CRF function and bind to its receptors may represent a new development of neuropsychiatric medicines to treat various stress-related disorders including depression, anxiety and addictive disorders [16, 17]. The main research into CRF antagonists to date has focused on non-peptide CRF1 receptor antagonists particularly fused pyrimidines with the aim of improving the health consequences of chronic stress and for use in the clinical management of anxiety and stress [18, 19]. Several CRF1 receptor antagonists from the fused pyrimidine series have been developed and are widely used in research, with the best-known agents being the selective CRF1 antagonist antalarmin, CP-154,526 and the newer drug pexacerfont (Fig.1).

Fig. (1).

Structure of prominent CRF receptor antagonists.

Antalarmin showed promising results in treatment of CRF-induced hypertension [20]. Promising results for antalarmin and other CRF1 antagonists were also observed in the area of drug addiction disorders. Antalarmin also showed anti-inflammatory effects and has been suggested as having potential uses in treatment of arthritis [21], irritable bowel syndrome [22, 23] and peptic ulcers [24]. CP-154,526 is a potent and selective CRF1 receptor antagonist developed by Pfizer [25, 26]. CP-154,526 is under investigation for the potential treatment of alcoholism [27]. Pexacerfont (BMS-562,086) is a recently developed CRF1 antagonist developed by Bristol-Myers-Squibb which is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of anxiety disorders [28] and has also been proposed to be useful for the treatment of depression and irritable bowel syndrome.

In this manuscript, we describe the synthesis and characterization of a new series of substituted thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidines carrying groups at selected positions similar to reported fused pyrimidines antagonists with superior CRF receptor antagonist activities. The synthesized compounds were evaluated for their binding affinities to CRF1 receptors and the selected compounds were evaluated for their effect on expression of genes associated with depression and anxiety disorders such as CRF1, CREB1, MAO-A, SERT, NPY, DatSLC6a3, and DBH, and showed a significant up-regulation of the CRF1 gene expression.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry

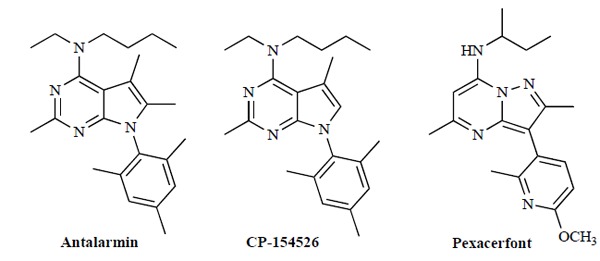

The general synthetic scheme of the target compounds is described in Scheme 1. The starting 4-amino-3-aryl-2-thioxo-2,3-dihydrothiazole-5-carboxamide derivatives (1a-b) were prepared in excellent yields by the reaction of the selected substituted phenyl isothiocyanate with cynoacetamide and sulfur in the presence of base following Gewald reaction [29-31]. Gewald first reported the synthesis of thiazole-2-thiones in 1966 and described the reaction of active-methylene containing nitriles with sulfur and phenyl isothiocyanates [29]. This synthesis has been widely utilized to synthesize various thiazoles [32-35] and was extended to include heterocyclic-containing nitriles [30]. This reaction can be carried out in dimethylformamide as a solvent at 50 oC, or in ethanol as a solvent at reflux temperature [36] or in a mixture of ethanol and dimethylformamide at reflux temperature. The selected isothiocyanates used were 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl isothiocyanate and 2-bromo-4-isopropylphenylisothiocyanate since previous studies on non-peptide CRF receptor antagonists have shown that these groups at position 3 of the thiazolo [4,5-d] pyrimidines have shown optimum CRF1 binding antagonist activity [37, 38].

Scheme (1).

Synthesis of the target 3-aryl-7-(N,N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidenes.

The stating thiazoles (1a-b) were then reacted with acetic anhydride at reflux temperature to yield 3-aryl-5-methyl-2-thioxo-2,3-dihydrothiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-7(6H)-ones (2a-b) [30, 31, 36].Ring closure of 4-amino-3-aryl-2-thioxo-2,3-dihydrothiazole-5-carboxamides giving 3-aryl-5-methyl-thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine-7(6H)-one-2-thiones, substituted with a methyl group at position 5 by heating at reflux temperature in acetic anhydride, was reported in 1998 and was described by Fahmy et al. [36, 39, 40]. The 3-aryl-5-methyl-2-thioxo-2,3-dihydrothiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-7(6H)-ones (2a-b) were subjected to chlorination using phosphorous oxychloride at reflux temperature according to the reported procedures for synthesis of thiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidines to yield 3-aryl-7-chloro-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine-2(3H)-thiones (3a-b) in excellent yields [36-40]. The 3-aryl-7-(N,N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine-

2(3H)-thiones (4a-j) were prepared by the reaction of the 3-aryl-7-chloro-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine-2(3H)-thiones (3a-b) with the selected secondary amines under the reported reaction conditions [30, 36, 37, 39]. The products were obtained in excellent yields and the cross reaction between the aromatic bromo group and amines were not observed. This may be due the fact that the pyrimidine chloro group is more activated compared to the bromo group on the benzene ring. The selected secondary amines for this reaction were N, N-diethyl amine, N, N-di(n-propyl)amine, N-ethyl-N-(n-butyl)amine, N,N-bis(2-methoxyethyl) amine and N-[2-(c-propyl)ethyl]-N-(n-propyl)amine since previous reports showed an optimum CRF1 receptor antagonist activity were obtained when those particular amino groups were found at position 7 of the thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine ring [37].

The target 3-aryl-7-(N,N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthia-zolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidenes (5a-v) derivatives were synthesized by the reaction of 3-aryl-7-(N, N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidine-2(3H)-thiones (4a-j) with dimethyl sulfate in acetonitrile at reflux temperature for 30 minutes, followed by reaction of the produced 2-methylthiazolium intermediate with the selected active methylene containing compound (malononitrile, ethyl cyanoacetate or diethyl malonate) in the presence of a base to give the target 3-aryl-7-(N,N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthia-zolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidenes (5a-v) in moderate yields. The replacement of the 2-thioxo function of 3-aryl-7-(N,N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidine-2(3H)-thiones with oxygen or amino functions was first described by Gewald [30, 31] and later was extended to replace the 2-thioxo function with active methylene-containing small molecules [30, 31] and active methylene containing large heterocyclic molecules.

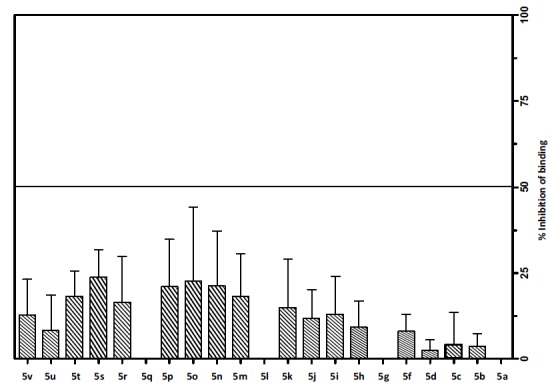

RECEPTOR BINDING STUDIES

The new series of 3-aryl-7-(N,N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidenes (5a-v) were evaluated for their binding affinity to CRF1 receptors. In this protocol [41], the ability of the tested compounds at a single concentration of 1000 nM to inhibit the specific binding of 125I-Tyr0 sauvagine to membranes from HEK 293 cells stably expressing the receptor in binding experiments performed under equilibrium conditions was evaluated (Fig. 2). Compounds 5s and 5o show approximately 25% inhibition of binding of radioligand on HEK 293 cells expressing CRF1 receptors.

Fig. (2).

Screening of compounds for binding to human CRF1 receptor. Inhibition of [125I]-Tyr0-sauvagine specific binding by 1000 nM of compounds 5a-u on membranes from HEK 293 cells stably expressing the human CRF1 receptor. The bars represent the % inhibition of radioligand specific binding by the compounds, determined from 2 to 5 experiments (with their means and S.E.).

MTT Assay

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazo-lium bromide) analysis was carried out at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h to detect the effect of 5c and 5f on the viability of RN46A cells. RN46A cells were treated with various concentrations of 5c and 5f (0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 5, 50 μM) during each stage. 5c and 5f showed no significant effects on the RN46A cell viability compared to the control at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h.

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

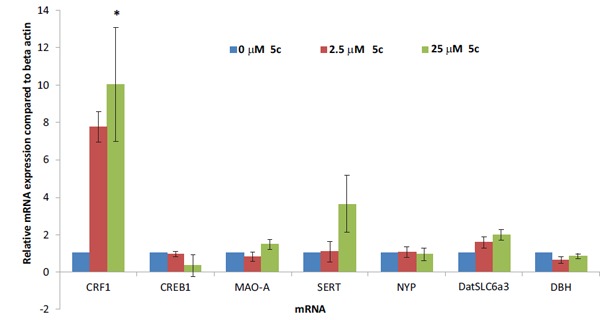

The currently used medications for treatment of mood disorders focus on neural circuitry of monoaminergic systems such as serotonin (5HT), norepinephrine (NE), and dopamine (DA) by preventing their enzymatic degradation or inhibiting reuptake from the presynaptic membranes. Genes associated with depression and anxiety disorders such as CRF1, CREB1 (cAMP responsive element binding protein 1), MAO-A (monoamine oxidase A), SERT (serotonin transporter), NPY (neuropeptide Y), DatSLC6a3 (dopamine transporter), and DBH (dopamine β-hydroxylase) were selected for this study. Being G-protein coupled receptor, CRF activates cAMP which in turn activates transcription factor CREB, thereby controlling gene expression. MAO-A is an enzyme that degrades the monoamines such as serotonin, adrenaline and dopamine, and terminates their actions, whereas NPY is neuropeptide that has been implicated in appetite, obesity and anxiety disorders. DatSLC6a3 is membrane spanning protein that pumps back dopamine from synaptic cleft to presynaptic membranes and terminates its actions. DBH is an enzyme which converts dopamine to norepinephrine. Real time PCR study was performed to evaluate the effect of the newly synthesized compounds on these targets and on their mRNA expression. Compounds 5c (with the 2-substitution is diethylmalonate-ylidene) and 5f (where the 2-substitution is maloninitrile-ylidene) were selected as representative for the new series of compounds to be used for gene expression studies. Compound 5c showed a significant effect on gene expression at 2.5µM and 25µM concentration (Fig. 3) for 24 h treatment in RN46A cell lines. However, the compound 5f showed no significant effect on gene expression at 0.5µM and 50µM concentration (Fig. 4).

Fig. (3).

Effects of 5c on mRNA expression of CRF1, CREB1, MAO-A, SERT, NYP, DatSLC6a3 and DBH in RN46A cells treated with compound 5c for 24 h. Values given are the means ± S.D (n=3). * denotes significant difference comparing with vehicle-treated cultures (p<0.05).

Fig. (4).

Effects of 5f on mRNA expression of CRF1, CREB1, MAO-A, SERT, NYP, DatSLC6a3 and DBH in RN46A cells treated with compound 5f for 24 h. Values given are the means ± S.D.

RN46 cells were treated with varying concentrations of 5c for 24 h, and the results show increased CRF1 mRNA expression in RN46Acells cultured in DMEM compared to cells cultured in media treated with vehicle (Fig. 3). CRF1 mRNA expression was increased to 7.76 fold (2.5 μM) and 10.04 fold (25 μM) compared to vehicle (control) group. Interestingly, there were no significant changes in CREB1, MAO-A, SERT, NYP, DatSLC6a3 and DBH mRNA expression following treatment with varying concentration of 5c for 24 h which indicates a selective effect on CRF1 mRNA expression.

Although, 5c showed modest inhibition to 125I-Tyr0-sauvagine binding to CRF1 receptor in HEK 293 cells at 1000 nM, it upregulated the CRF1 mRNA expression in RN46A cells compared to other genes. At this time, the molecular mechanism responsible for upregulation of CRF1 mRNA compared to other genes is not clear. However, it clearly indicates that these compounds have an effect on the CRF and that future studies are needed to further explore the cellular mechanism of action.

CONCLUSIONS

A new series of thiazolo4,5-dpyrimdines were synthesized as CRF receptor antagonists. Twenty two compounds were screened for the binding affinities to CRF receptors, where two compounds (5o and 5s) showed approximately 25% inhibition of radiolabeled 125I-Tyr0-sauvagine to CRF1 receptor in HEK 293 cells at 1000 nM. Two representative compounds of the new series (5c and 5f) were also screened for their effects on mRNA gene expression of neurotransmitters implicated in anxiety and depression in RN46A cells (CRF1, CREB1, MAO-A, SERT, NYP, DatSLC6a3 and DBH). Compound 5c showed significant up-regulation of the CRF1 compared to control and compared to other genes which indicates selective effect on CRF1 gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemistry

All Chemicals, secondary amines and dry solvents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich USA, Acros organics, Fisher scientific USA. The substituted phenyl isothiocyantaes were purchased from Oakwood Products, Inc. SC, USA. Flash column chromatography separation was performed using Acros organics silica gel 40-60 μm, 60A using combination of ethyl acetate and hexane. Whatman TLC plates were used for thin layer chromatography and visualization was done using UV fluorescence at 254 nm. Melting points were recorded on a Mel-Temp, Laboratory devices, Inc and were uncorrected. %CHN Analyzer by combustion/TCD and %S by O flask combustion/IC were used for elemental analysis and performed by Micro Analysis Inc., Wilmington DE, and all samples were within ±0.4%. 1H NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz instrument using CDCl3 as solvent unless otherwise stated. Chemical shifts are relative to TMS as an internal standard. Mass spectra were recorded on Finnigan LCQTM DECA by Thermo Quest San Jose, CA. All the reactions were carried out in flame dried glassware under an atmosphere of nitrogen unless otherwise stated.

4-amino-3-aryl-2-thioxo-2,3-dihydrothiazole-5-carboxa-mide (1a-b)

The thiazole-2-thiones were prepared from cyanoacetamide, sulfur, and the selected aromatic isothiocyanate under basic conditions in DMSO according to the reported procedures [37, 38].

3-aryl-5-substituted-2-thioxo-2,3-dihydrothiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidin-7(6H)-ones (2a-b)

The thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-7(6H)-ones were prepared from thiazoles 1a-b and acetic anhydride according to the reported procedures [37, 38].

3-aryl-7-chloro-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine-2(3H)-thiones (3a-b)

The chloro derivatives were prepared from 2a-b and phosphorous oxychloride according to the reported procedures [37, 38].

3-aryl-7-(N,N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidine-2(3H)-thiones (4a-j) [37, 38]

The amino derivatives were prepared from chloro derivatives 3a-b and the selected secondary amines in ethanol according to the reported procedures [37, 38].

3-aryl-7-(N, N-dialkylamino)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidenes (5a-v)

The 4a-j (1.0 mmol) and dimethyl sulfate (3.0 mmol) in acetonitrile (20 mL) were stirred at reflux temperature for about 3 to 4h and disappearance of 4a-j was monitored by TLC using ethyl acetate and hexanes. In another flask, appropriate active methylene compound (1.5 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (3.0 mmol) in acetonitrile (10 mL) were stirred at 0-5 oC for 30 minutes. Then, the above reaction mass was slowly added at 0-5 oC and stirred. Completion of the reaction was monitored by the TLC using ethyl acetate and hexane. The reaction was worked up by diluting with water followed by extraction with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layer was washed with water, brine solution, dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated under vacuum to get crude residue followed by flash chromatographic separation using gradient ethyl acetate and hexane to afford pure 5a-v derivatives.

2-(7-(Dipropylamino)-3-mesityl-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malononitrile 5a: Yield: white solid (51%); MP: 184 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.96 (s, 2 H), 3.52 - 3.43 (m, 4 H), 2.32 (s, 3 H), 2.28 (s, 3 H), 1.95 (s, 6 H), 1.65 (qd, J = 7.5, 15.3 Hz, 4 H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 6 H). MS m/z: 433.33 (MH)+ (C24H28N6S).

Ethyl 2-cyano-2-(7-(dipropylamino)-3-mesityl-5-meth-ylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)acetate 5b: Yield: off-white solid (23%); MP: 226 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.01 (s, 2 H), 4.26 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.66 - 3.57 (m, 4 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H), 2.34 (s, 3 H), 1.99 (s, 6 H), 1.75 (dq, J = 7.5, 15.3 Hz, 4 H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H), 1.02 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6 H). MS m/z: 480.23 (MH)+ (C26H33N5O2S).

Diethyl 2-(7-(dipropylamino)-3-mesityl-5-methylthia-zolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malonate 5c: Yield: white solid (31%); MP: 125 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.01 (s, 2 H), 4.26 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.66 - 3.57 (m, 4 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H), 2.34 (s, 3 H), 1.99 (s, 6 H), 1.75 (dq, J = 7.5, 15.3 Hz, 4 H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6 H), 1.02 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6 H). MS m/z: 528.29 (MH)+ (C28H38N4O4S).

2-(7-bis(2-methoxyethyl)amino-3-mesityl-5-methyl-thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malononitrile 5d: Yield: off-white solid (37%); MP: 162 o C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.04 (s, 2 H), 3.92 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 4 H), 3.66 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4 H), 3.39 (s, 6 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.03 (s, 6 H). MS m/z: 464.6 (MH)+ (C24H28N6O2S).

Ethyl 2-(7-bis(2-methoxyethyl)amino-3-mesityl-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)-2-cyano-acetate 5e: Yield: off-white solid (32%); MP: 135 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.03 (s, 2 H), 4.27 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 4.00 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 4 H), 3.70 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4 H), 3.39 (s, 6 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 1.99 (s, 6 H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H). MS m/z: 512.20 (MH)+ (C26H33N5O4S).

2-(7-Butyl(ethyl)amino-3-mesityl-5-methylthiazolo [4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malononitrile 5f: Yield: white solid (55%); MP: 171 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.04 (s, 2 H), 3.67 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.64 - 3.54 (m, 2 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.03 (s, 6 H), 1.74 - 1.65 (m, 2 H), 1.44 (dq, J = 7.4, 14.9 Hz, 2 H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H), 1.02 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3 H). MS m/z: 433.26 (MH)+ (C24H28N6S).

Ethyl-2-7-(butyl(ethyl)amino-3-mesityl-5-methyl-thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)-2-cyanoacetate 5g: Yield: off-white solid (33%); MP: 180 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.03 (s, 2 H), 4.27 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.74 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.70 - 3.60 (m, 2 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.00 (s, 6 H), 1.76 - 1.67 (m, 2 H), 1.46 (dq, J = 7.3, 15.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.32 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 6 H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3 H). MS m/z: 480.23 (MH)+ (C26H33N5O2S).

2-(7-(cyclopropylmethyl)(propyl)amino-3-mesityl-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene) malononitrile 5h: Yield: white solid (33%); MP: 115 oC; 1H NMR (400MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.04 (s, 2 H), 3.65 - 3.59 (m, 2 H), 3.57 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.03 (s, 6 H), 1.76 (dq, J = 7.4, 15.4 Hz, 2 H), 1.17 - 1.09 (m, 1 H), 1.02 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3 H), 0.67 - 0.60 (m, 2 H), 0.37 (q, J = 5.0 Hz, 2 H). MS m/z: 445.20 (MH)+ (C25H28N6S).

Ethyl 2-cyano-2-(7-(cyclopropylmethyl)(propyl)ami-no-3-mesityl-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)acetate 5i: Yield: off-white solid (23%); MP: 247oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.03 (s, 2 H), 4.27 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.73 - 3.67 (m, 2 H), 3.63 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.00 (s, 6 H), 1.79 (dq, J = 7.6, 15.3 Hz, 2 H), 1.32 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H), 1.21 - 1.13 (m, 1 H), 1.05 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3 H), 0.65-0.58 (m, 2 H), 0.41-0.34 (m, 2 H). MS m/z: 492.23 (MH)+ (C27H33N5O2S).

2-(7-(Diethylamino)-3-mesityl-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malononitrile 5j: Yield: white solid (39%); MP: 236 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.04 (s, 2 H), 3.68 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 2.03 (s, 6 H), 1.32 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6 H). MS m/z: 405.27 (MH)+ (C22H24N6S).

Ethyl 2-cyano-2-(7-diethylamino-3-mesityl-5-methyl-thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)acetate 5k: Yield: white solid (32%); MP: 221 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.03 (s, 2 H), 4.27 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.74 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.00 (s, 6 H), 1.33 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 9 H) . MS m/z: 452.24 (MH)+ (C24H29N5O2S).

2-(3-2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl-7-dipropylamino-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malononi-trile 5l: Yield: off-white solid (27%); MP: 193 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.62 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.38 (dd, J = 1.8, 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 3.55 (dd, J = 5.7, 8.7 Hz, 4 H), 3.02 (spt, J = 6.7 Hz, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.72 (dq, J = 7.4, 15.4 Hz, 4 H), 1.33 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 6 H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6 H). MS m/z: 511.27 (MH)+, 513.3 (MH+2)+ (C24H27BrN6S).

Ethyl 2-(3-2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl-7-dipropyl-amino-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)-2-cyanoacetate 5m: Yield: white solid (28%); MP: 236oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.36 (dd, J = 1.6, 8.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 3.62 (dt, J = 3.8, 7.7 Hz, 4 H), 3.03 (spt, J = 6.9 Hz, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.74 (sxt, J = 7.6 Hz, 4 H), 1.33 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6 H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H), 1.02 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6 H). MS m/z: 558.2 (MH)+, 560.2 (MH+2)+ (C26H32BrN5O2S).

2-(7-Bis(2-methoxyethyl)amino-3-(2-bromo-4-iso-propylphenyl)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malononitrile 5n: Yield: off-white solid (34%); MP: 149 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.63 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.40 - 7.36 (m, 1 H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 3.91 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4 H), 3.68 - 3.63 (m, 4 H), 3.38 (s, 6 H), 3.02 (spt, J = 6.9 Hz, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.33 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 6 H). MS m/z: 543.13 (MH)+, 545.13 (MH+2)+ (C24H27BrN6O2S).

Ethyl-2-(7-bis(2-methoxyethyl)amino-3-(2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl)-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidin-2(3 H)-ylidene)-2-cyanoacetate 5o: Yield: off-white solid (33%); MP: 152 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.62 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (dd, J = 1.8, 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (dq, J = 1.0, 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.98 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4 H), 3.72 - 3.66 (m, 4 H), 3.39 (s, 6 H), 3.03 (spt, J = 6.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.34 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 6 H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3 H). MS m/z: 590.2 (MH)+, 592.2 (MH+2)+ (C26H32BrN5O4S).

2-(3-{2-Bromo-4-isopropylphenyl}-7-butyl(ethyl) amino-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene) malononitrile 5p: Yield: white solid (37%); MP: 165 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.63 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.38 (dd, J = 1.9, 8.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 3.66 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.63 - 3.52 (m, 2 H), 3.09 - 2.96 (m, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.73 - 1.63 (m, 2 H), 1.48 - 1.38 (m, 2 H), 1.33 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 6 H), 1.31 - 1.24 (m, 3 H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3 H). MS m/z: 511.27 (MH)+, 513.3 (MH+2)+ (C24H27BrN6S).

Ethyl 2-(3-{2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl}-7-butyl(eth-yl)amino-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylide-ne)-2-cyanoacetate 5q: Yield: white solid (44%); MP: 184oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (dd, J = 1.8, 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (dq, J = 0.8, 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.73 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.69 - 3.62 (m, 2 H), 3.03 (spt, J = 6.9 Hz, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.70 (td, J = 7.6, 15.3 Hz, 2 H), 1.45 (dd, J = 7.4, 15.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.34 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6 H), 1.32 - 1.27 (m, 6 H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3 H). MS m/z: 558.3 (MH)+, 560.3 (MH+2)+ (C26H32BrN5O2S).

Diethyl 2-(3-{2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl}-7-butyl (ethyl)amino-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malonate 5r: Yield: off-white solid (17%); MP: 137 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (dd, J = 1.8, 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.73 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.69 - 3.62 (m, 2 H), 3.03 (spt, J = 6.9 Hz, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.70 (td, J = 7.6, 15.3 Hz, 2 H), 1.45 (dd, J = 7.4, 15.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.34 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6 H), 1.32 - 1.27 (m, 9 H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3 H). MS m/z: 605.2 (MH)+, 607.2 (MH+2)+ (C28H37BrN4O4S).

2-(3-2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl-7-{(cyclopropylme-thyl)(propyl)amino}-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] pyrimidin-2 (3H)-ylidene)malononitrile 5s: Yield: white solid (35%); MP: 168 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.63 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.40 - 7.36 (m, 1 H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 3.65 - 3.59 (m, 2 H), 3.57 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.08 - 2.97 (m, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.80 - 1.70 (m, 2 H), 1.33 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6 H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3 H), 0.66 - 0.59 (m, 2 H), 0.39 - 0.33 (m, 2 H). MS m/z: 523.27 (MH)+, 525.3 (MH+2)+ (C25H27BrN6S).

Diethyl 2-(3-2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl-7-{(cyclo-propylmethyl)(propyl)amino}-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d] py-rimidin-2(3H)-ylidene)malonate 5t: Yield: white solid (38%); MP: 108 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.63 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.40 - 7.36 (m, 1 H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.65 - 3.59 (m, 2 H), 3.57 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.08 - 2.97 (m, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 1.80 - 1.70 (m, 2 H), 1.33 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6 H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6 H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3 H), 0.66 - 0.59 (m, 2 H), 0.39 - 0.33 (m, 2 H). MS m/z: 617.27 (MH)+, 619.3 (MH+2)+ (C29H37BrN4O4S).

2-(3-2-Bromo-4-isopropylphenyl-7-diethylamino-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene) malononitrile 5u: Yield: off-white solid (110 mg, 21%); MP: 193oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.63 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.38 (dd, J = 1.6, 8.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 3.67 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.08 - 2.97 (m, 1 H), 2.38 (s, 3 H), 1.35 - 1.28 (m, 12 H). MS m/z: 483.3 (MH+), 485.4 (MH+2)+ (C22H23BrN6S).

Diethyl 2-(3-2-bromo-4-isopropylphenyl-7-diethyl-amino-5-methylthiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(3H)-ylidene) malonate 5v: Yield: white solid (23%). %); MP: 153 oC; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.63 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.38 (dd, J = 1.6, 8.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.67 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.08 - 2.97 (m, 1 H), 2.38 (s, 3 H), 1.35 - 1.28 (m, 12 H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6 H. MS m/z: 577.4 (MH)+, 579.5 (MH+2)+ (C24H29BrN4O2S).

Cell Culture

RN46A raphe-derived cell line was graciously provided by Scott R. Whittemore (University of Louisville School of Medicine). RN46A cells were cultured at 33°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium (DMEM) containing 100 units/ml penicillin, 100µg/ml streptomycin and 250 µg/ml G418. Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals Corp. Penicillin/streptomycin and G418 were ordered from Sigma-Aldrich.

MTT Assay

MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazol-ium bromide) assay was carried out using RN46A cells in 96-well culture plates at a density of 6×103 cells/well and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium (DMEM) containing 100 units/ml penicillin, 100µg/ml streptomycin and 250 µg/ml G418 and then supplemented with varying concentrations of 5c and 5f (0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 5, 50 μM). Medium was removed at different time points (24 h, 48 h, and 72 h) and MTT (0.5 mg/ml in DMEM, 50 μl/well) was added. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, followed by the addition of DMSO (150 μl/well), and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Optical density (OD) was measured at 570 nm with 650 nm as background.

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Real-Time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis was used to measure mRNA expression of human genes CRF1, CREB1, MAO-A, SERT, NYP, DatSLC6a3 and DBH under the control of β-actin. Briefly, RN46A cells following treatment with 5c and 5f for 24 h,total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. RNA was quantified using absorption of light at 260 and 280 nm, and sample integrity was checked by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. 0.8 μg of total RNA from each sample was used for reverse transcription reaction using the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was done using the SYBR green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The temperature cycling conditions of amplification were as follows: an initial step of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s. Real-Time RT-PCR was performed using Mx3000P Real-Time Thermocyclers (Statagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The relative mRNA levels of these genes were calculated by Pfaffl's mathematical method and normalized with control-treated groups [42].

CRF1 Receptor Binding Study

Binding studies were performed in membrane homogenates from human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293) stably expressing CRF1 receptors and using 125I-Tyr0-sauvagine as radioligand. Membrane homogenates were prepared according to the method of Gkountelias [41] CRF1 expressing HEK 293 cells, grown in DMEM/F12 (1:1) containing 3.15 g/L glucose, 10% bovine calf serum and 300 μg/ml of the antibiotic, Geneticin at 37 oC and 5% CO2, were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (4.3 mM Na2HPO4.7H20, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.2-7.3 at R.T). Then the cells were briefly treated with PBS containing 2 mM EDTA (PBS/EDTA), and then dissociated in PBS/EDTA. Cells suspensions were centrifuged at 1000 x g for 5 min at room temperature, and the pellets were homogenized in 1.5 ml of buffer H (20 mM HEPES, containing 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 0.2 mg/ml bacitracin and 0.93 μg/ml aprotinin pH 7.2 at 4 oC) using a Janke & & Kunkel IKA Ultra Turrax T25 homogenizer, at setting ~20, for 10-15 sec, at 4 oC. The homogenates were centrifuged at 16000 x g, for 10 min, at 4 oC. The membrane pellets were re-suspended by homogenization, as described above, in 1 ml buffer B (buffer H containing 0.1% BSA, pH 7.2 at 20 oC). The membrane suspensions were then diluted in buffer B and aliquots of suspensions (50 μl) were added into tubes containing buffer B and 20-25 pM 125I-Tyr0sauvagine without or with non-peptide 5a-v at the single concentration of 1000 nM in a final volume of 0.2 ml. The mixtures were incubated at 20-21 °C for 120 min and then filtered through Whatman 934AH filters, presoaked for 1 h in 0.3% polyethylene imine at 4 °C. The filters were washed 3 times with 0.5 ml of ice-cold PBS, pH 7.1 containing 0.01% Triton X-100 and assessed for radioactivity in a gamma counter. The amount of membranes used was adjusted to insure that the specific binding was always equal to or less than 10% of the total concentration of the added radioligand. Specific 125I-Tyr0-sauvagine binding was defined as total binding less nonspecific binding in the presence of 1000 nM antalarmin.

Statistical Analysis

Student t test was used for data analysis and significance was considered at P < 0.05 (*).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Table 1.

substitutions, molecular formulae and molecular weights of target compounds (5a-v).

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial support for this study was provided by the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, South Dakota State University, Brookings, South Dakota, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 1981;213(4514):1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Physiology and pharmacology of corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43(4):425–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoumakis E, Rice KC, Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Potential uses of corticotropin-releasing hormone antagonists. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;1083:239–251. doi: 10.1196/annals.1367.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7(3 ):254–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grigoriadis DE. The corticotropin-releasing factor receptor: a novel target for the treatment of depression and anxiety-related disorders. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2005;9(4 ):651–684. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen P, Vaughan J, Donaldson C, Vale W, Li C. Injection of Urocortin 3 into the ventromedial hypothalamus modulates feeding, blood glucose levels, and hypothalamic POMC gene expression but not the HPA axis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;298(2):E337–345. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00402.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarnyai Z, Biro E, Gardi J, Vecsernyes M, Julesz J, Telegdy G. Brain corticotropin-releasing factor mediates 'anxiety-like' behavior induced by cocaine withdrawal in rats. Brain Res. 1995;675(1-2):89–97. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00043-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George O, Ghozland S, Azar MR, Cottone P, Zorrilla EP, Parsons LH, O'Dell LE, Richardson HN, Koob GF. CRF-CRF1 system activation mediates withdrawal-induced increases in nicotine self-administration in nicotine-dependent rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(43):17198–17203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707585104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter RE, Korzan WJ, Bockholt C, Watt MJ, Forster GL, Renner KJ, Summers CH. Corticotropin releasing factor influences aggression and monoamines: modulation of attacks and retreats. Neuroscience. 2009;158(2):412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and stress. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1167–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Souza EB. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors: Physiology, pharmacology, biochemistry and role in central nervous system and immune disorders. Psycho-neuroendocrinology. 1995;20(8):789–819. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arato M, Banki CM, Bissette G, Nemeroff CB. Elevated CSF CRF in suicide victims. Biol. Psychiatry. 1989;25(3):355–359. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross MJ, Kahn JP, Laxenaire M, Nicolas JP, Burlet C. Corticotropin-releasing factor and anorexia nervosa: reac-tions of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis to neurotropic stress. Ann. Endocrinol. 1994;55(6):221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raadsheer FC, van Heerikhuize JJ, Lucassen PJ, Hoogendijk WJ, Tilders FJ, Swaab DF. Corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA levels in the paraventricular nucleus of patients with Alzheimer's disease and depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152(9):1372–1376. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitehouse PJ, Vale WW, Zweig RM, Singer HS, Mayeux R, Kuhar MJ, Price DL, De Souza EB. Reductions in corticotropin releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in cerebral cortex in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 1987;37(6):905–909. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kehne JH, Maynard GD. CRF1 receptor antagonists: treatment of stress-related disorders. Drug Discovery Today: Ther. Strategies. 2008;5(3):161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehne JH, Cain CK. Therapeutic utility of non-peptidic CRF1 receptor antagonists in anxiety, depression, and stress-related disorders: evidence from animal models. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010;128(3):460–487. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilligan PJ, Robertson DW, Zaczek R. Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) receptor modulators: Progress and opportunities for new therapeutic agents. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43(9):1641–1660. doi: 10.1021/jm990590f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. Progress in corticotropin-releasing factor-1 antagonist development. Drug Discovery Today. 2010;15(9-10):371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briscoe RJ, Cabrera CL, Baird TJ, Rice KC, Woods JH. Antalarmin blockade of corticotropin releasing hormone-induced hypertension in rats. Brain Res. 2000;881(2):204–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02742-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webster EL, Barrientos RM, Contoreggi C, Isaac MG, Ligier S, Gabry KE, Chrousos GP, McCarthy EF, Rice KC, Gold PW, Sternberg EM. Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) antagonist attenuates adjuvant induced arthritis: role of CRH in peripheral inflammation. J. Rheu-matol. 2002;29(6):1252–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Johnson AC, Cochrane S, Schulkin J, Myers DA. Corticotropin-releasing factor 1 receptor-mediated mechanisms inhibit colonic hypersensitivity in rats. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2005;17(3):415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez V, Tache Y. CRF1 receptors as a therapeutic target for irritable bowel syndrome. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006;12(31):4071–4088. doi: 10.2174/138161206778743637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabry KE, Chrousos GP, Rice KC, Mostafa RM, Sternberg E, Negrao AB, Webster EL, McCann SM, Gold PW. Marked suppression of gastric ulcerogenesis and intestinal responses to stress by a novel class of drugs. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7(5):474–483. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulz DW, Mansbach RS, Sprouse J, Braselton JP, Collins J, Corman M, Dunaiskis A, Faraci S, Schmidt AW, Seeger T, Seymour P, Tingley FD 3rd, Winston EN, Chen YL, Heym J. CP-154,526: a potent and selective nonpeptide antagonist of corticotropin releasing factor receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93(19):10477–10482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griebel G, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Characterization of the behavioral profile of the non-peptide CRF receptor antagonist CP-154,526 in anxiety models in rodents. Comparison with diazepam and buspirone. Psychopharmacology. 1998;138(1):55–66. doi: 10.1007/s002130050645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastor R, McKinnon CS, Scibelli AC, Burkhart-Kasch S, Reed C, Ryabinin AE, Coste SC, Stenzel-Poore MP, Phillips TJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor-1 receptor involvement in behavioral neuroadaptation to ethanol: a urocortin1-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(26):9070–9075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710181105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coric V, Feldman HH, Oren DA, Shekhar A, Pultz J, Dockens RC, Wu X, Gentile KA, Huang SP, Emison E, Delmonte T, D'Souza BB, Zimbroff DL, Grebb JA, Goddard AW, Stock EG. Multicenter, randomized, dou-ble-blind, active comparator and placebo-controlled trial of a corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-1 antagonist in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression Anxiety. 2010;27(5):417–425. doi: 10.1002/da.20695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gewald K, Schinke E, Böttcher H. Heterocyclen aus CH-aciden Nitrilen, VIII 2-Amino-thiophene aus methylenaktiven Nitrilen, Carbonylverbindungen und Schwefel. Chem. Ber. 1966;99(1):94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gewald K, Hain U, Hartung P. Zur Chemie der 4-Aminothiazolin-2-thione. Monatshefte fur Chemie. 1981;112(12):1393–1404. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gewald K, Hain U, Schindler R, Gruner M. Zur Chemie der 4-Amino-thiazolin-2-thione, 2. Mitt. Monatshefte fur Chemie. 1994;125(10):1129–1143. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sridhar M, Rao RM, Baba NHK, Kumbhare RM. Microwave accelerated Gewald reaction: synthesis of 2-aminothiophenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48(18):3171–3172. [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Mekabaty A. Chemistry of 2-Amino-3-carbethoxythiophene and Related Compounds. Synth. Commun. 2014;44(1):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mundy BP, Ellerd MG, Favaloro FG. In: Name reactions and reagents in organic synthesis. 2nd ed. Hoboken N.J : Wiley:; 2005. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eller GA, Holzer W. First Synthesis of 3-Acetyl-2-aminothiophenes using the Gewald Reaction. Molecules. 2006;11(5):371–376. doi: 10.3390/11050371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fahmy HT, Rostom SA, Saudi MN, Zjawiony JK, Robins DJ. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of the anticancer activity of novel fluorinated thiazolo[4, 5-d]pyrimidines. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim. Ger) 2003;336(4-5):216–225. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200300734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck JP, Curry MA, Chorvat RJ, Fitzgerald LW, Gilligan PJ, Zaczek R, Trainor GL. Thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine thiones and -ones as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH-R1) receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9(8):1185–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck J. Thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidines and pyridines as Corticotropin Releasing Factor (CRF) antagonists WO Patent. 1999051608 Oct 14. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badawey E, Rida SM, Hazza AA, Fahmy HTY, Gohar YM. Potential anti-microbials II Synthesis and in vitro anti-microbial evaluation of some thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1993;28(2):97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badawey E, Rida SM, Hazza AA, Fahmy HTY, Gohar YM. Potential anti-microbials I Synthesis and structure-activity studies of some new thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidine derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1993;28(2):91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gkountelias K, Tselios T, Venihaki M, Deraos G, Lazaridis I, Rassouli O, Gravanis A, Liapakis G. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the second extracellular loop of type 1 corticotropin-releasing factor receptor revealed residues critical for peptide binding. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;75(4):793–800. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu Y, Fahmy H, Zjawiony JK, Davies GE. Inhibitory effect and transcriptional impact of berberine and evodiamine on human white preadipocyte differentiation. Fitoterapia. 2010;81(4):259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]