Abstract

In an epidemiologic and case-control study including 30 case patients over a 3.5-year period in a Taiwanese university hospital, only β-lactamase inhibitor use and extended-spectrum cephalosporin use were identified as independent risk factors for nosocomial CMY-2-producing Escherichia coli bloodstream infection, and CMY-2 producers were found more prevalent than extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing isolates.

The prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and plasmid-encoded AmpC enzymes in gram-negative bacilli has been rising in response to the extended use of extended-spectrum cephalosporins in health-care settings and animal husbandry (2, 3, 8, 13, 18). AmpC enzymes, unlike ESBLs, are not inhibited by β-lactamase inhibitors and cephamycins (2, 13). The ESBLs found most commonly are TEM, SHV, and CTX-M derivatives (2). Of the acquired AmpC enzymes, CMY-2 is the most prevalent and is distributed in many countries, including Taiwan (13, 19). The present study was conducted to determine risk factors for bacteremias caused by CMY-2-producing Escherichia coli because knowledge in this regard remains limited. The recent trend in the prevalence of ESBLs in E. coli at a Taiwanese teaching hospital was also investigated.

Bloodstream E. coli isolates from patients aged ≥18 years were consecutively collected from January 1999 to June 2002 at the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, a 900-bed hospital in Taiwan. When multiple isolates had been recovered from a single patient, the first isolate was chosen. Thus, a total of 1,034 isolates were evaluated and 1 and 8 of the isolates have been previously known to produce CTX-M-3 and CMY-2, respectively (19, 20). Of the remaining 1,025 isolates, 83 demonstrated resistance to cefoxitin or reduced susceptibility to cefpodoxime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, or aztreonam in the standard disk diffusion tests (9). The 83 isolates were further tested by the disk diffusion confirmatory tests for ESBLs as previously described (9), and ESBL production was suggested in 17 of them. Of the 66 isolates negative by the ESBL confirmatory tests, 34 were cefoxitin resistant.

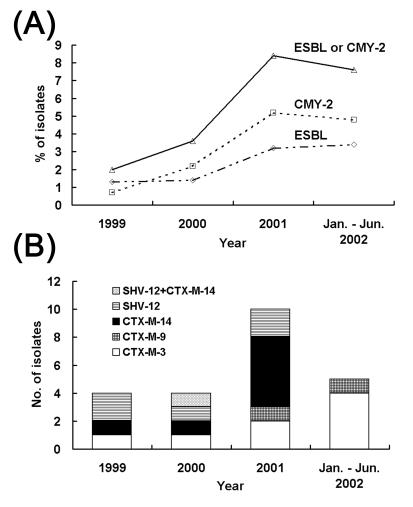

β-Lactamases produced by the 34 cefoxitin-resistant isolates and 17 putative ESBL producers were detected by isoelectric focusing and the enzyme inhibition assay as previously described (12, 19). Genotypes of β-lactamases were determined by PCR assays with FastStart Taq polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) and previously described oligonucleotide primers to amplify blaTEM (6), blaSHV (11), blaCTX-M-1-related (15), blaCTX-M-9-related (15), and blaCMY-2 (18) genes. PCR products were purified, and both strand were sequenced twice. The results of β-lactamase typing are summarized in Table 1. The expression of β-lactamases with pIs of >9.0, 9.0, and 8.8 was inhibited by 0.3 mM cloxacillin but not by 0.3 mM clavulanic acid, suggesting that these β-lactamases are AmpC enzymes (12, 13). ESBLs were also detected in 5 of the 34 cefoxitin-resistant isolates. pI 7.9 β-lactamases were detected in 10 isolates, of which 8 and 2 were found to carry blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-9, respectively. This is the first report of the appearance of CTX-M-9 in Taiwan. The prevalence rates of ESBLs and CMY-2 among bloodstream E. coli isolates appeared to increase during the study period, and the proportion of CMY-2 producers has become higher than that of all ESBL producers together since 2000 (Fig. 1). CTX-M-type β-lactamases remained the most prevalent ESBLs, and CTX-M-3 and CTX-M-14 were the most common variants of CTX-M-type enzymes.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the 17 E. coli isolates positive by the ESBL confirmatory tests and the 34 cefoxitin-resistant E. coli isolates negative by the ESBL confirmatory tests

| Result of ESBL confirmatory tests and pI(s) of β-lactamase(s) | β-Lactamase(s) | No. of isolates | MIC range (μg/ml)a

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMX | AMC | CXM | FOX | CAZ | CTX | ATM | FEP | IPM | |||

| Positive | 17 | ||||||||||

| 8.4, 5.4 | CTX-M-3, TEM-1 | 4 | >256 | 16-32 | >256 | 4-16 | 2-16 | 32->64 | 8-64 | 8-64 | 0.13-0.5 |

| 7.9 | CTX-M-14 | 3 | >256 | 8 | >256 | 8-16 | 4-64 | 32-64 | 8-32 | 4-16 | 0.25-0.5 |

| 7.9, 5.4 | CTX-M-14, TEM-1 | 4 | >256 | 8-32 | >256 | 4-32 | 1-16 | 16-64 | 2-16 | 2-64 | 0.13-0.5 |

| 7.9, 5.4 | CTX-M-9, TEM-1 | 2 | >256 | 8-16 | >256 | 8 | 0.5-1 | 16-16 | 1 | 4 | 0.25-0.5 |

| 8.2 | SHV-12 | 1 | >256 | 32 | 64 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 8.2, 5.4 | SHV-12, TEM-1 | 2 | >256 | 16 | 128-256 | 4 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 8 | 0.5-1 |

| 8.2, 7.9, 5.4 | SHV-12, CTX-M-14, TEM-1 | 1 | >256 | 32 | >256 | 16 | 64 | >64 | 64 | >64 | 0.5 |

| Negative | 34 | ||||||||||

| 9.0 | CMY-2 | 2 | >256 | 32-64 | 64-256 | 128-256 | >64 | 16-64 | 8-32 | 0.25-2 | 0.25 |

| 9.0, 5.4 | CMY-2, TEM-1 | 20 | >256 | 32-128 | 64->256 | 64->256 | 32->64 | 8->64 | 4-64 | <0.13-2 | 0.13-1 |

| 9.0, 8.4, 5.4 | CMY-2, CTX-M-3, TEM-1 | 1 | >256 | 64 | 256 | 256 | >64 | 64 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| >9.0, 8.2, 5.4 | AmpC, SHV-12, TEM-1 | 2 | >256 | 32-64 | >256 | >256 | ≥64 | 32-64 | 16-64 | 16 | 0.5 |

| 8.8, 8.4, 5.4 | AmpC, CTX-M-3, TEM-1 | 1 | >256 | 32 | 256 | 64 | >64 | 64 | 16 | 8 | 0.5 |

| >9.0, 8.4, 5.4 | AmpC, CTX-M-3, TEM-1 | 1 | >256 | 32 | >256 | >256 | >64 | >64 | >64 | 64 | 0.5 |

| 8.8, 5.4 | AmpC, TEM-1 | 7 | >256 | 32-128 | 32-64 | 64-128 | 2-16 | 0.5-8 | 2-16 | <0.13 | 0.13-0.5 |

AMX, amoxicillin; AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; CXM, cefuroxime; FOX, cefoxitin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; ATM, aztreonam; FEP, cefepime; IPM, imipenem.

FIG. 1.

(A) Prevalence rates of ESBLs and CMY-2 among bloodstream E. coli isolates collected between January 1999 and June 2002 at the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan. (B) Numbers of bloodstream E. coli isolates producing various ESBLs in each year. One CTX-M-3-producing isolate and eight CMY-2-producing isolates recovered in 1999 and 2000 have been described previously (19, 20).

MICs for the ESBL producers and cefoxitin-resistant isolates were determined by the standard agar dilution method with E. coli ATCC 25922 as the control strain (10). The antimicrobial agents tested and the results are shown in Table 1.

Thirty-one CMY-2 producers identified previously and in this study were subjected to randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis with primer ERIC2 as previously described (7, 17). RAPD patterns that differed by more than one band on visual inspection were deemed different. The 31 isolates gave 17 different patterns (A to Q). Patterns A, D, J, and K were displayed by four, two, seven, and five isolates, respectively, and two subtypes were obtained for each of these patterns. Each of the other 13 patterns was displayed by a single isolate. The 18 isolates with identical or similar RAPD patterns were further analyzed by ribotyping with endonucleases EcoRI and HindIII (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) as described previously (12, 14), and the results were interpreted in accordance with the criteria of Tenover et al. (16), which are now considered appropriate for genotyping analyses by gel electrophoresis, including pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and ribotyping (1). Overall, four major ribotypes (H1 to H4), including 8 subtypes, were generated with HindIII, and six major ribotypes (E1 to E6), including 12 subtypes, were generated with EcoRI. Two pattern J isolates displayed ribotypes H4c and E5, two pattern J isolates displayed ribotypes H4c and E6b, and two pattern K isolates displayed ribotypes H2a and E2a. All of the other 12 isolates tested were different in either RAPD patterns or ribotypes (data not shown). The results of RAPD analysis and ribotyping indicate that the increase in the number of CMY-2-producing E. coli bacteremias was not due to nosocomial outbreaks of infections caused by epidemic strains.

A matched case-control study was conducted to identify risk factors for CMY-2-producing E. coli infection. One case patient infected with the isolate coproducing CMY-2 and CTX-M-3 was excluded from the analysis. Cases were matched in a 1:2 ratio to controls who had been bacteremic with E. coli isolates susceptible to both cephamycins and extended-spectrum cephalosporins; matching was based on the closest date to the isolation of a CMY-2-producing isolate. Demographic and clinical data collected from each chart for analysis are listed in Table 2, and the definitions of these variables are described in the footnotes to the table or elsewhere (5). Categorical variables were compared by univariate analysis with the χ2 or Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were compared by the Student t test. Stepwise logistic regression models determined significant predictors and interactions. All statistical calculations were done with the SPSS software package (version 10.0). All tests were two tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

TABLE 2.

Clinical data for patients infected by CMY-2-producing E. coli and for control patients

| Variable | Value for group

|

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case patients (n = 30)a | Control patients (n = 60)a | |||

| General characteristics | ||||

| Mean age (yr) ± SD | 60.9 ± 15.9 | 65.9 ± 14.1 | 0.14 | |

| Male sex | 12 (40.0) | 23 (38.3) | 1.07 (0.44-2.63) | 0.88 |

| Nosocomial infection | 22 (73.3) | 21 (35.0) | 5.11 (1.94-13.44) | 0.001 |

| Nosocomial infection at National Cheng Kung University Hospital | 18 (60.0) | 17 (28.3) | 3.79 (1.51-9.53) | 0.006 |

| Duration of hospital stay prior to bacteremia (mean no. of days ± SD)b | 37.2 ± 52.8 | 25.2 ± 24.8 | 0.40 | |

| Housed in an intensive care unit | 3 (10.0) | 3 (5.0) | 2.11 (0.4-11.15) | 0.40 |

| Transfer from outside hospital | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | 0.97 (0.92-1.01) | 0.55 |

| Nursing home residence | 4 (13.3) | 2 (3.3) | 4.46 (0.77-25.91) | 0.09 |

| APACHE II score (mean ± SD)c | 17.1 ± 6.8 | 13.3 ± 6.3 | 0.01 | |

| Focus of infection | ||||

| Urinary tract | 13 (43.3) | 35 (58.3) | 0.55 (0.22-1.32) | 0.18 |

| Biliary tract | 1 (3.3) | 6 (10.0) | 0.31 (0.04-2.70) | 0.42 |

| Wound | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 1.15 (1.00-1.33) | 0.01 |

| Lungs (pneumonia) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1.07 (0.97-1.18) | 0.11 |

| Instrumentation | ||||

| Mechanical ventilator | 3 (10.0) | 4 (6.7) | 1.56 (0.32-7.45) | 0.68 |

| Urinary catheter | 7 (23.3) | 6 (10.0) | 3.35 (0.96-11.64) | 0.048 |

| Central venous catheter | 5 (16.7) | 6 (10.0) | 1.80 (0.50-6.46) | 0.50 |

| Comorbid condition | ||||

| Solid-organ malignancy | 15 (50.0) | 20 (33.3) | 2.0 (0.82-4.89) | 0.13 |

| Hematological malignancy | 2 (6.7) | 3 (5.0) | 1.36 (0.21-8.59) | 1.00 |

| Neutropeniad | 4 (13.3) | 2 (3.3) | 4.46 (0.77-25.91) | 0.09 |

| Diabetes | 9 (30.0) | 19 (31.7) | 0.92 (0.36-2.39) | 0.87 |

| Renal insufficiencye | 10 (33.3) | 9 (15.0) | 2.83 (1.00-8.00) | 0.04 |

| Hepatic dysfunctionf | 10 (33.3) | 19 (31.7) | 1.08 (0.42-2.74) | 0.87 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4 (13.3) | 4 (6.7) | 2.15 (0.50-9.29) | 0.43 |

| Surgery in previous 1 mo | 6 (20.0) | 1 (1.7) | 14.75 (1.68-129.12) | 0.005 |

| Immunosuppressive agent use in previous 1 mo | 11 (36.7) | 8 (13.3) | 3.76 (1.31-10.77) | 0.01 |

| Steroid use in previous 1 mo | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1.07 (0.97-1.18) | 0.11 |

| Transplantation | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1.03 (0.97-1.11) | 0.33 |

| Trauma in previous 1 mo | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | 1.00 |

| Use of antibiotics for at least 24 h in previous 1 mo | ||||

| Any antibiotics | 21 (70.0) | 18 (30.0) | 4.67 (1.82-11.93) | 0.001 |

| Penicillins or narrow- or extended-spectrum cephalosporins | 10 (33.3) | 11 (18.3) | 2.00 (0.74-5.37) | 0.16 |

| β-Lactamase inhibitors | 5 (16.7) | 2 (3.3) | 6.00 (1.67-21.58) | 0.04 |

| Cephamycins | 5 (16.7) | 2 (3.3) | 5.80 (1.05-31.93) | 0.04 |

| Broad-spectrum cephalosporins | 6 (20.0) | 1 (1.7) | 14.75 (1.68-129.12) | 0.005 |

| Aminoglycosides | 5 (16.7) | 4 (6.7) | 2.80 (0.69-11.32) | 0.15 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 6 (20.0) | 1 (1.7) | 14.75 (1.68-129.12) | 0.005 |

Data are numbers of patients (percentages) unless otherwise indicated.

Cases of nosocomial infection at the National Cheng Kung University Hospital only.

APACHE, Acute Physiological and Chronic Health Evaluation (4).

Absolute neutrophil count of <500/mm3.

Presence of a creatinine level of >2.0 mg/dl or requirement of dialysis (5).

Presence of two or more of the following: a bilirubin concentration of >2.5 mg/dl, an aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase level more than twice normal, or known liver disease (5).

Multiple factors were associated with CMY-2-producing E. coli bacteremia in the univariate analysis (Table 2), and among these factors, nosocomial infection was found to be the most significant variable in the multivariate analysis. Logistic regression analysis showed a significant correlation between nosocomial CMY-2-producing E. coli infection and two variables: prior extended-spectrum cephalosporin use (P = 0.009) and prior β-lactamase inhibitor use (P = 0.02). In the subset analysis of community-acquired infection, renal insufficiency (P = 0.003) and prior use of penicillins or narrow- or extended-spectrum cephalosporins (P = 0.001) were independently associated with CMY-2-producing E. coli infection. The mortality rate due to bloodstream infection for case patients (7 of 30 patients [23.3%]) was significantly higher than that for control patients (4 of 60 patients [6.7%]) (P = 0.04). Our study suggests that β-lactamase inhibitors, in addition to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, should be used under scrutiny in health-care settings where plasmid-determined AmpC enzymes are prevalent.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grant NSC 92-2320-B-006-088 from the National Science Council, Taiwan, and grant NCKUH 91-36 from the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbeit, R. D. 1999. Laboratory procedures for the epidemiologic analysis of microorganisms, p. 116-137. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Bradford, P. A. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:933-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fey, P. D., T. J. Safranek, M. E. Rupp, E. F. Dunne, E. Ribot, P. C. Iwen, P. A. Bradford, F. J. Angulo, and S. H. Hinrichs. 2000. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infection acquired by a child from cattle. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1242-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knaus, W. A., E. A. Drapier, D. P. Wagner, and J. E. Zimmerman. 1985. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 16:128-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lautenbach, E., J. B. Patel, W. B. Bilker, P. H. Edelstein, and N. O. Fishman. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: risk factor for infection and impact of resistance on outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1162-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mabilat, C., and S. Goussard. 1993. PCR detection and identification of genes for extended-spectrum β-lactamases, p. 553-559. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Manges, A. R., J. R. Johnson, B. Foxman, T. T. O'Bryan, K. E. Fullerton, and L. W. Riley. 2001. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1007-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros, A. A. 1997. Evolution and dissemination of β-lactamases accelerated by generations of β-lactam antibiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24(Suppl. 1):S19-S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 8th ed. Approved standard M2-A8. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 11.Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. T., H. Hächler, and F. H. Kayser. 1996. Detection of genes coding for extended-spectrum SHV beta-lactamases in clinical isolates by a molecular genetic method, and comparison with the E test. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15:398-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pai, H., S. Lyu, J. H. Lee, J. Kim, Y. Kwon, J.-W. Kim, and K. W. Choe. 1999. Survey of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: prevalence of TEM-12 in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1758-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philippon, A., G. Arlet, and G. A. Jacoby. 2002. Plasmid-determined AmpC-type β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popovic, T., C. A. Bopp, Ø. Olsvik, and J. A. Kiehlbauch. 1993. Ribotyping in molecular epidemiology, p. 573-589. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Saladin, M., V. T. B. Cao, T. Lambert, J.-L. Donay, J.-L. Herrmann, Z. Ould-Hocine, C. Verdit, F. Delisle, A. Philippon, and G. Arlet. 2002. Diversity of CTX-M β-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Versalovic, J., T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1991. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6823-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winokur, P. L., D. L. Vonstein, L. J. Hoffman, E. K. Uhlenhopp, and G. V. Doern. 2001. Evidence for transfer of CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase plasmids between Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals and humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2716-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan, J.-J., W.-C. Ko, S.-H. Tsai, H.-M. Wu, Y.-T. Jin, and J.-J. Wu. 2000. Dissemination of CTX-M-3 and CMY-2 β-lactamases among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli in southern Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4320-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan, J.-J., W.-C. Ko, C.-H. Chiu, S.-H. Tsai, H.-M. Wu, and J.-J. Wu. 2003. Emergence of ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella isolates and rapid spread of plasmid-encoded CMY-2-like cephalosporinase, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:323-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]