Abstract

Context

The 5 major tobacco-growing states (Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) are disproportionately affected by the tobacco epidemic, with higher rates of smoking and smoking-induced disease. These states also have fewer smoke-free laws and lower tobacco taxes, 2 evidence-based policies that reduce tobacco use. Historically, the tobacco farmers and hospitality associations allied with the tobacco companies to oppose these policies.

Methods

This research is based on 5 detailed case studies of these states, which included key informant interviews, previously secret tobacco industry documents (available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu), and media articles. This was supplemented with additional tobacco document and media searches specifically for this article.

Findings

The tobacco companies were particularly concerned about blocking tobacco-control policies in the tobacco-growing states by promoting a pro-tobacco culture, beginning in the late 1960s. Nevertheless, since 2003, there has been rapid progress in the tobacco-growing states’ passage of smoke-free laws. This progress came after the alliance between the tobacco companies and the tobacco farmers fractured and hospitality organizations stopped opposing smoke-free laws. In addition, infrastructure built by National Cancer Institute research projects (COMMIT and ASSIST) led to long-standing tobacco-control coalitions that capitalized on these changes. Although tobacco production has dramatically fallen in these states, pro-tobacco sentiment still hinders tobacco-control policies in the major tobacco-growing states.

Conclusions

The environment has changed in the tobacco-growing states, following a fracture of the alliance between the tobacco companies and their former allies (tobacco growers and hospitality organizations). To continue this progress, health advocates should educate the public and policymakers on the changing reality in the tobacco-growing states, notably the great reduction in the number of tobacco farmers as well as in the volume of tobacco produced.

Keywords: tobacco-control policy, tobacco farmers, tobacco manufacturers, tobacco-growing states

Policy Points.

The tobacco companies prioritized blocking tobacco-control policies in tobacco-growing states and partnered with tobacco farmers to oppose tobacco-control policies.

The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, which settled state litigation against the cigarette companies, the 2004 tobacco-quota buyout, and the companies’ increasing use of foreign tobacco led to a rift between the companies and tobacco farmers.

In 2003, the first comprehensive smoke-free local law was passed in a major tobacco-growing state, and there has been steady progress in the region since then.

Health advocates should educate the public and policymakers on the changing reality in tobacco-growing states, notably the major reduction in the volume of tobacco produced.

Tobacco is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States,1 and the 5 major tobacco-growing states (Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) are disproportionately burdened by tobacco-induced diseases.2,3 In 2012 when the national smoking prevalence was 19.0%,4 Kentucky led the nation with a 29% smoking prevalence, and 3 of the other 4 major tobacco-growing states were above the national average. Tobacco-control policies, including tobacco taxes and smoke-free policies, reduce tobacco use and exposure to secondhand smoke and the attendant disease burden.1 Part of the reason tobacco-growing states face higher rates of tobacco-induced morbidity is that they have lagged behind the rest of the country in enacting such policies. Tobacco taxes are low,5 and tobacco-growing states have less coverage by comprehensive (covering workplaces, restaurants, and bars) clean indoor air laws.6

Although the tobacco industry generally opposes tobacco taxes and smoke-free laws across the country, tobacco-growing states have faced particular challenges from the tobacco industry. The tobacco industry works through a policy network,7 which includes tobacco-area legislators, agricultural interest groups (eg, farm bureaus), and commissioners of agriculture. The tobacco industry has been especially concerned about blocking tobacco taxes in tobacco states, has promoted a pro-tobacco social norm in these states, and has succeeded in winning state laws that preempt local clean indoor air laws in tobacco-growing states. Despite these obstacles, in 2003 (when the first strong smoke-free local law passed in Kentucky), all 5 tobacco-growing states started enacting tobacco-control policies, particularly strong smoke-free laws. This progress in public health was achieved through a combination of long-standing public health coalition activity and changing alliances between tobacco manufacturers and tobacco growers and hospitality organizations, which helped weaken the policy network that supported the tobacco industry.

Methods

Our data sources for this project include 5 case studies chronicling the history of tobacco-control policy in 5 tobacco-growing states,8–12 based on public records, key informant interviews, media articles, and previously secret internal tobacco industry documents available in the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (legacy.library.ucsf.edu). We collected additional information from the American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation Local Ordinance Database, media articles (LexisNexis), published research literature, and the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library. We searched these databases using standard snowball methods,13 beginning with the terms “tobacco-growing states,” “tobacco producing states,” “tobacco tax,” “smoking ban,” “smoke-free policy,” “clean indoor air law,” and “Pride in Tobacco.” These searches were followed by searches using the names of key individuals and organizations and adjacent (Bates numbers) documents in the Legacy Library.

Results

Before the Tobacco Price Support System: Prior to 1933

The major tobacco-growing states have long-standing ties to the crop. Tobacco was introduced in Virginia as early as 1613 and stabilized its economy as its sole cash crop.11

The time before 1933 was characterized by disagreement and animosity between the tobacco farmers and the tobacco manufacturers14–16 over the price of tobacco leaf. By the 1890s, thanks to their cigarette-rolling machine, James Duke and the American Tobacco Company controlled 90% of US tobacco sales.17 In the early 1900s, partly because of this lack of competition, tobacco farmers in Tennessee were receiving less for their tobacco than it cost to produce. Farmers formed a collaborative, “The Dark Tobacco District Planter's Protective Association of Kentucky and Tennessee,” to sell tobacco and improve their economic situation.14,16,18 When the prices of tobacco did not rise, a militant faction of the farmers called the “Night Riders” formed and burned the tobacco crops of farmers who were selling outside the association to the American Tobacco Company.

In 1911, the US Supreme Court ruled that the American Tobacco Company had violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and accordingly broke it up into 4 tobacco companies: American Tobacco Company (a smaller version), RJ Reynolds, Liggett & Meyers, and Lorillard.16 Even so, the farmers still felt that these 4 major tobacco companies controlled the price of tobacco at auction. By 1929, when the Great Depression started, tobacco farmers were increasingly facing a crisis of low tobacco prices and uncertainty at the auctions.

The Early Era of the Tobacco Price Support System: 1933-1952

To assist tobacco growers, in 1933 Congress mandated the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Tobacco Price Support Program as part of the New Deal.19 This program, which was voted on by growers through referenda (initially every year and then every 3 years), limited production through a quota system (based first on an acreage allotment and, later, on pounds) that set a minimum price for tobacco.20,21 The USDA based each year's quota on a formula that depended on demand from the manufacturers, which created the farmers’ and manufacturers’ common interest in increasing the demand for cigarettes.16,22

During World War II (1939-1945), the demand for US flue-cured tobacco increased when it was introduced to more markets throughout the world.16 This led J.B. Hutson, head of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration's tobacco branch, to form Tobacco Associates in 1947 “to promote, develop and expand export markets for US produced flue-cured tobacco and REPRESENT THE FARMERS’ INTEREST in maintaining and protecting the total tobacco program [emphasis in original].”23 Tobacco Associates was originally funded by growers, bankers, and warehousemen and then later by quota holders (farmers).16

By 1940, more than half the states had enacted a cigarette tax to raise revenue.24 In 1949, the industry formed the Tobacco Tax Council,25 including all segments of the industry from growers to retailers,25 to “combat unconscionable, inequitable and discriminatory taxes on cigarettes and other manufactured tobacco products,”26 with funding largely from the manufacturers.27–31 From the beginning, the Tobacco Tax Council opposed tobacco taxes, arguing that low taxes protected tobacco farmers.32

In December 1952, Reader's Digest published “Cancer by the Carton,” which emphasized the link between smoking and lung cancer,33 triggering a wave of public concern about smoking and proposals to regulate cigarettes and cigarette marketing.34 At the time “Cancer by the Carton” was published, both the tobacco-growing and the non-tobacco-growing states taxed cigarettes at similarly low rates, assessed as the average rate of taxation on each pack at the end of the time period (1921-1952; tobacco-growing states: 2.17¢, other states: 2.88¢; the tobacco-growing states averaged 75% of the non-tobacco-growing states).24

Increased Partnership Between the Growers and the Manufacturers: 1953-1970

Once the health effects of smoking became more widely known, tobacco manufacturers and growers had a greater incentive to work together.16 In December 1953, the major tobacco company presidents, as well as J.B. Hutson, president of Tobacco Associates,35 created the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC) to influence public and legislative thinking about tobacco and health, in order to blunt demands for government regulation of tobacco products and their marketing.

The TIRC's first act was to run the advertisement “A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers” in newspapers and magazines all over the country, in which the industry assured the public that “we accept an interest in people's health as a basic responsibility, paramount to every other consideration in our business.”36 In addition to the cigarette companies (American Tobacco Company, Inc., Benson & Hedges, Brown & Williamson Tobacco Company, Larus & Brother Company, Inc., Lorillard Company, Philip Morris & Co., Ltd., Inc., RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company, and United States Tobacco Company), the grower and warehouse organizations (Bright Belt Warehouse Association, Burley Auction Warehouse Association, Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative Association, Maryland Tobacco Growers Association, and Tobacco Associates, Inc.) signed the Frank Statement.36

In 1958, the major cigarette companies formed the Tobacco Institute37 to provide a coordinated lobbying and public relations response to public health pressure on the companies. This response included disseminating the TIRC's scientific findings,38 which were designed to reassure the public that the scientific questions about smoking and health remained unresolved. The Tobacco Tax Council focused predominantly on tax issues, whereas the Tobacco Institute was broader, covering “legislative and regulatory problems on smoking issues, research, communications, and legal work.”39

In 1958, the Tobacco Growers Information Committee (TGIC) was formed as a partnership between growers and the tobacco manufacturers, as a public relations tool to “provide information to tobacco growers and to represent the view of the nation's tobacco growers on public policy issues which affect the American tobacco industry,” with major ongoing funding from Tobacco Associates and the Tobacco Institute.40–44 For example, 17 years later, in 1985/1986, the Tobacco Institute contributed $45,000 and Tobacco Associates contributed $35,000 to the TGIC. The next largest contribution was $6,000 from the Council for Burley Tobacco, followed by many donations of less than $1,000 (eg, the Bright Belt Warehouse Association and the North Carolina Farm Bureau Federation each contributed $500). According to a presentation by a vice president of the Tobacco Institute to the Burley Leaf Tobacco Dealers Association, the TGIC was “doing a vitally important job by alerting every tobacco grower to the threats against this industry and their livelihood and enlisting them actively in the fight…a real grass-roots job, clearing the record with editors, business leaders and opinion leaders in many fields.”45

Particular Concern for the Tobacco-Growing States and the Promotion of a Pro-Tobacco Social Norm: 1970-1985

By 1969, the Tobacco Institute had developed a strategy, which was executed in the 1970s, to use films as a public relations tool to lobby policymakers, oppose tobacco-control policies, and normalize tobacco growing. An example was Leaf, which was produced in 1974. It was the Tobacco Institute's most popular film, and it portrayed farming as a family tradition that honored previous generations and was an important source of jobs.46 The promotion of a pro-tobacco social norm continued as a strategy to oppose tobacco-control policy.

Those organizations that represented both the tobacco manufacturers and growers also were concerned with holding back tobacco-control interventions, particularly taxes, beginning in the late 1960s.23,47–51 The Tobacco Tax Council recognized the importance of keeping tobacco taxes low in the tobacco-growing states to prevent tax increases elsewhere. In 1970, Tobacco Tax Council President William O'Flaherty told participants at the 12th annual meeting of the TGIC in Raleigh, North Carolina,

One thing did happen that we predicted—that a cigaret [sic] tax in North Carolina would have a “domino effect.” Many states felt that if North Carolina would impose a tax on cigarets [sic], its number one commodity, then why should they worry. The flood gates were opened in a number of states, and 15, to be exact, increased their cigaret [sic] tax rates in exorbitant degrees.51

Herbert Maddock, vice president of the Tobacco Tax Council, echoed this sentiment in a 1977 statement titled “The War Is Not Over”:

The tax man is still at the door. The only reason he has not gotten more than his foot in for the past five years is that we have been holding the door shut against him…the greatest danger of this happening lies in the low-tax states. At this very moment an increase bill has been proposed in North Carolina, while four such bills have already been defeated in Virginia. Are these proposals dangerous? The answer to that lies in reviewing what happened when North Carolina initially passed a tax. That was 1969…the dominoes began to fall. Before it was all over, eighteen other states and D.C. joined North Carolina in one of the greatest tax increase bonanzas we have ever seen…there is no doubt for one second that, should North Carolina again be the low-tax state to pass an increase, we will see exactly the same domino effect take place.52 [emphasis added]

A report in 1979 from the president of Tobacco Associates to the membership in Raleigh, North Carolina, also reflected this sentiment:

Flue-cured tobacco farmers of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia must be militant to prevent tax increases in these major tobacco producing states. If producing states permit tax increases then it greatly weakens the efforts of the Tax Council in non-producing states. The health controversy may ebb, crest and subside, but a tax levied is forever.53 [emphasis added]

This concern still existed in August 1990 when Philip Morris included an “action alert” in its publication Smokers’ Advocate54 stating that a proposed tobacco tax in North Carolina needed to be stopped because

North Carolina is a bellwether state when it comes to tobacco. Any change in existing tax rates will trigger a domino effect throughout the nation. At a time when tobacco is increasingly under attack throughout the rest of the country, North Carolinians need to “circle the wagons” and protect the economic future of as important a crop as tobacco.55

By the end of the 1970s, tobacco-growing culture was being promoted as a way to oppose tobacco regulation. In 1976, Tobacco Tax Council President O'Flaherty described the objectives of the council's “North Carolina Campaign” as “(1) defeat any proposal to increase the cigaret [sic] tax rate; (2) to re-educate the citizens as to the importance of tobacco.” A 1979 slide presentation titled “North Carolina Grows on Tobacco,” by the Tobacco Tax Council and the North Carolina Agribusiness Council, stated,

Since colonial times, tobacco has been North Carolina's leading money crop and, as such, a vital factor in the lives and fortunes of all North Carolinians. Through wars…depressions…and every kind of weather…North Carolina has continued to grow on tobacco, the golden leaf…and the benefits have followed to every segment of North Carolina's economy.56

To solicit the farmers’ opposition to tobacco-control policies, the presentation explained,

Yet, on the horizon there has been one threat that could do untold damage to North Carolina's number one industry. The threat is in the form of an increased state cigarette tax. This threat concerns the consumer…the farmer…the manufacturer…our state's revenue.

The presentation ended with a call to action: “Your help is needed today to keep the tobacco economy strong. You have the power to see to it that North Carolina does hold the line in the matter of cigarette and tobacco product taxes.…Remember, North Carolina grows on tobacco!”56

By 1978, the RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company had created “Pride in Tobacco” to promote this pro-tobacco culture and oppose tobacco-control policies, and in 1979, Pride in Tobacco meetings attracted 9,000 tobacco people.57 The program had considerable reach, with “the ‘Pride in Tobacco’ Newsline, a twice monthly newsletter, [having] a circulation larger than the majority of weekly newspapers in the country.”58 The program conveyed its message through news releases, billboards, and also materials such as bumper stickers, posters, window decals, baseball caps, stamps, and brochures.

A draft 1981 presentation in RJ Reynolds’ files titled “Pride in Tobacco” described the policy atmosphere at the time and Pride in Tobacco's goal of reframing the discussion of smoking and health to one of the economic importance of tobacco:

In 1978, the future of the tobacco industry was clouded. The smoking-and-health barrage had been going on for twenty-five years, per capita consumption was down, and the industry was facing a non-growth situation. The “passive smoking” situation was escalating.

The country had a new Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare—Mr. [Joseph A.] Califano [Jr.]—who appeared determined to advance his personal career by killing an industry that had been a backbone of this country's heritage for over three hundred years.

It was time for every segment of the industry to speak up. There was no reason for anyone in the tobacco industry to feel ashamed of what they did for a living.

From the start, it was decided that the primary health issue would not be directly addressed through this program. The Tobacco Institute had the responsibility for advancing the industry's position on this matter.

The socioeconomic importance of tobacco to the country would be the focus of this new effort.

In seeking ways to promote the industry's viewpoint of key issues, we looked first to the tobacco “family,” that group of farmers, warehousemen, employees, and agri-business interest whose livelihoods depend on tobacco.

We thought that through the tobacco family, the word could be spread in state capitols [sic], Washington, and the news media that the tobacco industry was far from being dead and that we were united in opposition to unfounded attacks.

The slogan “Pride in Tobacco” evolved because it seemed to capsulize what we were trying to achieve for the tobacco community. In 1978, the program had two key objectives: first, achieve the greatest possible visibility for the “Pride in Tobacco” program to help demonstrate the size and importance of the tobacco industry; and secondly, to build broad public and political awareness of the economic importance of tobacco.59

According to an RJ Reynolds Sales Department presentation to Customer Association Meetings, titled “Public Affairs Overview on Tobacco Political Issues,” “in states where it [Pride in Tobacco] has been introduced, the ‘Pride’ program has unified the entire tobacco family from growers to retailers, to better understand tobacco legislative issues and to take positive action when necessary.”57 An RJ Reynolds interoffice memorandum in 1990 illustrated the program's continuing reach, stating, “The ‘Pride in Tobacco’ program has been represented at 15 events in North Carolina, South Carolina, Wisconsin, Ohio, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. A total of 10,600 signatures in support of the company's Smokers’ Rights Program were gathered, and we completed 47 media interviews.”60

A 1978 Tobacco Institute newsletter stated that “RJ Reynolds ‘Pride in Tobacco’ campaign won praise in four North Carolina newspapers.”61 Examples are “Those of us in tobacco country have stood by in embarrassment and shame and have silently taken the abuse for too long. It's time for us to tell our story” (Greenville Reflector). The campaign “not only is appropriate, it is important to North Carolina” (Goldsboro News-Argus). “The embattled tobacco community must unite in developing a counterattack to bolster its image” (Wilmington Star). “North Carolinians have nothing to be ashamed about in the production of tobacco products” (Franklin Times).61

The 1970s also marked the start of the clean indoor air movement, particularly in 4 non-tobacco-growing states: Arizona, California, Minnesota, and Florida.62,63 In response, the tobacco manufacturers started developing smokers’ rights groups.64 Although these groups were created to appear to be a grassroots movement because of the industry's low credibility with the public, they actually were created, funded, and managed by the cigarette companies.54,64–67

State preemption of local legislation also became a central strategy for stopping the emerging clean indoor air movement in the 1980s,68 when the cigarette companies realized that they were losing battles over smoking restrictions at the local level. The companies did this by securing the passage of weak state laws that nominally addressed tobacco-control needs (such as laws promoting voluntary “accommodation” between smokers and nonsmokers rather than legislation requiring smoke-free restaurants and bars69) while preempting the authority of local jurisdictions (where public health forces are often stronger) to enact tobacco-control policies.68,70,71

The first preemptive state law was passed in Florida in 1985 with the support of the American Cancer Society and other health groups.72 In March 1992, the American Cancer Society resolved in State Preemption of Local Tobacco Control Laws: “That the American Cancer Society opposes any preemption clauses that are intended to remove or restrict power and authority from a unit of local government or regulate clean indoor air and/or other tobacco control laws.”73 Nonetheless, between 1985 and 2010, 25 preemptive state smoke-free laws were passed, and 13 remained as of November 2014.74 The most recent preemptive statewide smoke-free law was passed in Wisconsin in 2010. As we discuss in more detail later, the issue of preemption reemerged as a major issue in the tobacco-growing states, which were still disproportionately affected by preemption.

In 1994, Tina Walls, Philip Morris's director of government affairs, explained the company's well-established goal of preemption in a presentation to the company's lobbyists:

The anti-smoking movement has become more sophisticated in its efforts to enact bans and restrictions on smoking. In addition to pursuing statewide restrictions, they have adopted a “PAC-man” strategy where they attempt to gobble up one community at a time.…The solution to “PAC-man” is statewide preemption. By introducing preemptive statewide legislation we can shift the battle back to the state legislatures where we are on stronger ground. And when we pass preemptive statewide legislation we can stop the PAC-man dead in his tracks.71

In 1977, the Tobacco Institute began coordinating the Tobacco Action Network, which consisted of tobacco company employees, vendors, and wholesalers, as an “umbrella organization to coordinate the activities of the tobacco industry in its defense against attacks by the anti-smoking movement.”75 The Tobacco Action Network originally did not include tobacco-growing states because the manufacturers could rely on grower organizations,9 but as the pro-tobacco climate in tobacco-growing states began to weaken, the Tobacco Institute expanded the Tobacco Action Network to include them.76 A legislative update of the Tobacco Institute State Activities Division in 1981 stated, “One prediction that can be made safely is that even the major tobacco producing states are not free from anti-tobacco legislation.”77 According to an expansion of the update that same year for the Tobacco Action Network, “The attack on tobacco is national in scope. Countering it requires a unified, coordinated national effort…the tobacco growing states are not immune to anti-tobacco efforts. Many potentially-damaging proposals have been introduced in state legislatures and local communities throughout the southeast.”76

By the 1980s, the tobacco price support program had become controversial because of the growing recognition of the health effects of smoking, which led to the federal No Net Cost Tobacco Act of 1982.22 This law required that the tobacco price support program be implemented without cost to the US Treasury. By the mid-1980s, Philip Morris was concerned that the switch to the No Net Cost Tobacco Act of 1982 was just a temporary fix and that the end of the price support system would negatively impact the relationship between the manufacturers and the growers because the growers were benefiting from the program by stabilizing the price of tobacco and supporting their income.15,19 As a Philip Morris Washington Relations Office Issues Briefing Book explained in 1985:

It is becoming increasingly apparent that the “No Net Cost” provision was merely a band aid on a mortal wound; there is a growing possibility that the tobacco price support program, and the manner in which the U.S leaf industry operates may collapse inward, nudged by external Congressional pressure. And if, and perhaps when, the system collapses, that tenuous bond that allied the growers and manufacturers will deteriorate.78

The Philip Morris Issues Briefing Book also explained the industry's position on the quota system:

Aside from the industry's insistence that “it wants an assured supply of quality tobacco at a competitive price,” and will support any program that can deliver these elements, the fact is the current tobacco program maintains an artificially high price of domestic tobacco in relation to the world market. Should the domestic tobacco program collapse we would return to a free market system which would probably result in considerably lower prices without a significant sacrifice of quality. Consequently, manufacturers would be perceived as benefiting at the expense of the small tobacco growers and warehousemen who have built the cigarette industry to a position of high profitability, with the profits going only to the major corporations. And it will be perceived by many of these tobacco farmers that it was done, deliberately, by the manufacturers to the growers.78

The briefing book goes on to explain the potential ramifications of changing the quota system for the relationships between the manufacturers and the growers:

…some former allies could become instant adversaries. There is the harsh political reality that there are approximately one-half million of them and approximately one-half dozen of us. And when it comes to political representation in the United States Congress, that Representative will opt for the interest of the half million versus the half dozen…if the program collapses, so will go the traditional support of many of these congressional Representatives who have previously been the backbone of the “powerful tobacco lobby.”78

From the 1970s through the mid-1980s, the tobacco companies were particularly concerned about the tobacco-growing states and held back tobacco-control policies through the promotion of a pro-tobacco social norm. By the mid-1980s, as the tobacco price support system was becoming increasingly controversial, the companies realized their relationship with the growers was becoming more tenuous.

Developing the Health Advocates’ Infrastructure: 1986-2000

By late 1989, many local communities in Virginia had enacted some kind of smoking restrictions. In response to this activity, in 1990, the legislature enacted the Virginia Indoor Clean Air Act (VICAA), a weak law that merely required restaurants with more than 50 seats to designate a nonsmoking area and exempted bars. The VICAA also preempted passage of local smoke-free ordinances after January 1, 1990. The Tobacco Institute praised the law in an article for the Richmond News Letter, stating, “We think Virginia's sensible level of accommodation should be a model for other states who are pressured into enacting smoking restrictions into law.”79

North Carolina health advocates were also winning local smoking restrictions. By 1993, 22 cities and 15 counties had enacted smoking restrictions in public places. In response, encouraged by a Tobacco Institute lobbyist, the North Carolina legislature passed a statewide law in 1993 that preempted future local activity and required public government buildings; public transportation and vehicles, arenas, auditoriums, and theaters; and restaurants with seating for more than 50 to set aside 20% of their space for smoking. In the 90 days between when the law was signed and the preemption took effect, health advocates passed 89 more smoke-free board of health regulations and city and county laws.9

In 1986, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) launched the Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation (COMMIT, which ran from 1986 to 1995), a randomized trial of community-based interventions to increase smoking cessation rates among heavy smokers.80 The COMMIT intervention included public education, training health care providers, and promoting cessation in worksites and cessation resources. These activities required identifying, organizing, and training tobacco-control advocates to promote this change in norms. North Carolina was the only tobacco-growing state to participate in COMMIT. The state's goal was increasing smoking cessation among heavy smokers by 10% in the intervention community (Raleigh) over that of the control community (Greensboro). While COMMIT failed to increase smoking cessation rates among heavy smokers,80 it did have a lasting impact on North Carolina tobacco control because of the development of a strong coalition, the North Carolina Tri-Agency Council. The Tri-Agency Council, consisting of the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, and the American Lung Association, initially focused on education and raising public awareness and, by the 1990s, was supporting clean indoor air policies.9

One possible explanation for COMMIT's failure to reduce smoking was that the intervention was too limited.81 To test this hypothesis, the NCI developed the American Stop Smoking Intervention Study (ASSIST, which ran from 1991 to 1999), a state-level intervention focused on changing social norms through policy change and capacity building. Three tobacco-growing states participated in ASSIST: North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia.82

The North Carolina Health Department administered North Carolina's ASSIST contract, the first major tobacco-control program led by the department. Although the tobacco companies lobbied Governor James Martin (R) to divert ASSIST money to other public health funds, they failed because the money was allocated specifically to tobacco control.9 North Carolina's ASSIST program goals were to promote smoking cessation and change social norms in the community, health care settings, schools, and workplaces by recruiting community groups. Between 1991 and 1995, the North Carolina ASSIST coalition expanded from 24 to 270 organizations, which promoted smoke-free efforts and supported North Carolina's burgeoning clean indoor air movement.9

South Carolina participated in ASSIST through its Department of Health and Environmental Control. As in North Carolina, ASSIST was the Department of Health and Environmental Control's first organized tobacco-control effort. Because of fear of tobacco industry retaliation, the South Carolina ASSIST coalition did not have a strong policy focus, instead giving priority to reducing youth access to tobacco and to promoting voluntary smoke-free policies. Nevertheless, ASSIST created the Alliance for a Smoke-Free South Carolina, the state's first tobacco-control coalition.10

The goals of the ASSIST project of the Virginia Department of Health's Division of Health Education were to promote local clean indoor air laws, comply with the VICAA, establish voluntary smoking restrictions in public places, restrict tobacco advertising, and raise the state's tobacco tax. But Virginia's ASSIST efforts were hampered by the tobacco industry, which used tactics such as overwhelming the ASSIST 800 number during phone banking and submitting Freedom of Information Act requests to coincide with ASSIST's deadlines. Ultimately, ASSIST in Virginia turned to issues that were less threatening to the tobacco industry, such as youth tobacco use and voluntary smoke-free policies.11

The presence of a major Philip Morris facility hampered Virginia's ASSIST efforts. According to a member of the Virginia ASSIST coalition, it was difficult to find legislative support for ASSIST because “there's this acceptance in Virginia that tobacco is so strong—Philip Morris is so strong that you kind of have to accept that you're not going to be as progressive as another state.”11 Nevertheless, ASSIST did manage to strengthen Virginia's tobacco coalition. In 1992, the state had 6 local tobacco coalitions; by 1998, it had 17 local coalitions and a statewide coalition. The University of Virginia's Institute for Quality Health, an ASSIST partner, received a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation SmokeLess states grant to foster partnership between tobacco growers and health advocates, which led to the Southern Tobacco Communities Project in 1997.11 The goal of the Southern Tobacco Communities Project was to build a relationship among health groups, farmers, and community development groups in the 5 major tobacco-growing states plus Georgia.83

Health advocates and farmers worked together to develop the 1998 Core Principles84 document, whose purpose was to “actively work together to accomplish two goals: first, to reduce tobacco use in this country, especially among children and adolescents; and second, to stabilize the tobacco producers’ communities as consumption declines into the 21st century.”85 The Core Principles statement was signed by more than 100 groups, health advocates (including the American Heart Association, the American Cancer Society, the Kentucky affiliate of the American Lung Association, and the American Public Health Association), and tobacco interests (Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative and the Flue-Cured Tobacco Stabilization Corporation).84

This partnership between the tobacco growers and public health groups was solidified in 2000, when President Bill Clinton (D) formed the President's Commission on Improving Economic Opportunity in Communities Dependent on Tobacco Production While Protecting Public Health to “provide advice to the President on changes occurring in the tobacco farming economy and recommend such measures as may be necessary to improve economic opportunity and development in communities that are dependent on tobacco production, and protect consumers, particularly children, from hazards associated with smoking.”86 Both tobacco farming and public health interests also agreed that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should have authority to regulate the distribution, labeling, manufacturing, marketing, and sale of tobacco products.87 An example of an outcome of this partnership (described in more detail later) is the president of the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative working with Kentucky ACTION (a tobacco-control coalition) to endorse a state tobacco tax in 2003.

The Divergence of Economic Interests Between Cigarette Companies and Farmers: 1990-2000

The Tobacco Companies’ Activities. In the 1990s, Philip Morris sought to “improv[e] the political climate within tobacco producing and manufacturing states and in Washington” in order to “continue to manufacture and sell…products profitably.”88 The company recognized that “a continuing effort must be made to insure that tobacco growers in every state appreciate the gravity of the public affairs issues facing the tobacco industry.” According to a strategy document,

At every opportunity, PM [Philip Morris] personnel who speak to farm and agricultural types should use the opportunity to mention public affairs issues. Just five years ago the only significant public affairs issue facing growers was whether there would even be a tobacco program. Now tobacco tax increases, restrictive smoking laws and tobacco export bans pose a real threat to the livelihood of all segments of the industry—INCLUDING GROWERS. We must hammer this home at every opportunity.88 [emphasis in original]

Philip Morris wanted to make working with growers a priority because “local growers have more credibility in legislatures than do hired guns.”88

One element of Philip Morris's strategy was to work with the Tobacco Growers Information Committee. According to a planning document for Philip Morris's Agricultural, Plant Community, Government and Public Affairs,

The Tobacco Growers Information Committee is operated under the auspices of the Flue-Cured Stabilization Corporation. The TGIC mailing list includes virtually every producer in the country, and because Stabilization is a grower organization, TGIC has credibility with growers that manufacturers don't have. I suggest we fund the informational activities of TGIC to the greatest extent possible.88

In the 1990s, the Pride in Tobacco program continued to oppose tobacco-control policies. A 1990 RJ Reynolds interoffice memorandum regarding the federal excise tax, from the executive vice president of external affairs to the chairman and chief executive officer, stated,

Under the banner of our “Pride in Tobacco” program PR staff members participated in the Daniel Boone Pioneer Festival in Kentucky, gathering FET [federal excise tax] opposition signatures at our smokers’ rights booth.…TV and newspaper exposure in surrounding Kentucky areas included coverage of smokers’ rights issues as well as tobacco's contribution to the economy.89

Likewise, the manager of Pride in Tobacco sent a “call to action” to supporters urging opposition to a smoke-free law under consideration in Burlington, North Carolina:

If you feel that these restrictions are as harsh as we do, let the Burlington [North Carolina] City Council hear from you. Call them or schedule a personal visit. Tell them these harsh restrictions aren't necessary…you might also remind the Burlington City Council that flue-cured tobacco is grown on more than 350 farms in Alamance County, and that it's the county's largest cash crop…you might want to let the city council know that if they pass this ordinance, they will be thumbing their noses at the thousands of Alamance County residents who enjoy tobacco or depend on it for their livelihood.90

Nevertheless, in March 1993, Burlington enacted the law.9

Strained Relationship Between the Companies and the Growers. Despite a history of working together, the relationship between the companies and the growers became increasingly strained in the late 1990s because of 2 factors. First, the demand for US tobacco was falling because smoking rates were falling91 and US cigarette manufacturers were increasingly using less expensive foreign tobacco.87 This decision to purchase less expensive foreign tobacco was described in a 1971 memo from RJ Reynolds vice president of manufacturing,William D. Hobbs, on “Tobacco Usage, a Long Range Plan” to achieve the goals of “1. To maintain or improve our existing operating profit through proposed new blends, while excluding all expected manufacturing efficiencies. 2. Lower nicotine levels by use of the same blends.”92 Hobbs wrote:

In the auction season just concluded, we spent approximately three hundred million dollars for tobacco. Applying this to our 1969 annual report, it is roughly 32% of our current assets. With two crop years’ storage requirements, this constitutes 64% of our current assets. It also represents 64% of our variable costs. We are faced with rising costs in other areas.…Coupled with these internal cost pressures, we have the external pressures of the present social environment of anti-smoking groups, Federal agencies which continue to harass our industry, plus an unfriendly Congress, and State and local governing bodies that constantly seek more revenue dollars by means of a higher cigarette tax.…

Foreign tobacco quality, both flue-cured and burley, in recent years have improved tremendously. Imported smoking tobaccos are gaining in popularity every day. The cigar industry is advertising “imported Havana-type tobaccos” and gaining. Foreign tobacco is for the most part low in nicotine, and of course, is substantially cheaper than our domestic. Acreage allotments in this country are being reduced every year while the support prices are increased. But a bill by Senator [Frank] Moss [D-UT] has been introduced in the Senate to cease supports entirely in 1972, which would then cause the farmer to raise other crops. So why should we not examine foreign tobacco as another source of raw material?92

Second, throughout the 1990s, both policymakers and the general public increasingly discussed ending the tobacco price support program.93-95 Adding to the farmers’ growing discontent, in 2000 Philip Morris began circumventing the quota system by contracting directly with farmers to buy tobacco before the auction, at a pre-agreed price rather than the federally controlled auction system, which increased risk for farmers.96 By 1997, 81% of North Carolina farmers reported that the tobacco companies’ support of foreign tobacco threatened the future of American tobacco farming.97

Also in the 1990s, the tobacco manufacturers were facing lawsuits from states (and others) regarding tobacco-induced health care costs. Some health advocates and state attorneys general negotiated with the cigarette companies to develop a “global settlement” that would have resolved this litigation. The global settlement would have limited future lawsuits in a way that offered effective immunity to the tobacco industry from future lawsuits in exchange for money payments and industry agreements to some tobacco-control measures, including limited FDA regulation of tobacco products and marketing.98,99 Because of the proposed limitations on future lawsuits and the FDA provisions, the global settlement was more than a conventional settlement between litigating parties and thus required congressional action, which was introduced by Senator John McCain (R-AZ).99,100 The McCain bill also included a tobacco quota buyout.10 While the tobacco companies initially supported the McCain bill, they switched to opposing it when the immunity provisions were removed because of opposition from some elements of the public health community.

Once they turned against the McCain bill, the tobacco companies began encouraging the tobacco farmers to oppose it, promising them $28 billion in payments through a future settlement (what became the Master Settlement Agreement [MSA]).96 The tobacco companies convinced the farmers that they would benefit more from the settlement if it was reached without congressional influence.96

McCain's bill failed, and in 1998, the more limited MSA was negotiated between the state attorneys general and the defendant tobacco companies to settle the states’ litigation against the companies. The MSA included cash payments to the settling states and some limitations on marketing tobacco to youth.99 (Because the settlement applied only to the parties in the cases, it could not limit future litigation by others or grant FDA authority over tobacco.) To participate in the settlement (including the money it provided to the states), a state had to have filed suit against the cigarette companies. Once the MSA was negotiated, the 4 states that had not yet sued (Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia, all major tobacco-growing states) were given 30 days to file suit and join the settlement.

The MSA was a pivotal moment in the history of tobacco control in the tobacco-growing states. Implementing it marked the first time tobacco-control advocates and farmers worked together on a legislative issue. As had been agreed in the Core Principles document, the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative passed a resolution in 1999 supporting the allocation of funding to youth smoking prevention.101 According to a statement in the Lexington Herald Leader from the executive director of Kentucky ACTION, this resolution was important because

having the burley growers’ support a youth tobacco prevention and cessation campaign is very powerful…because the legislature in Kentucky is primarily rural, public health advocates—on tobacco issues—have historically not had great success…the endorsement could change that…the burley growers and agriculture members have agreed that we need to give money, time and attention to funding a youth campaign statewide.101(pA1)

In Virginia, after the Southern Tobacco Communities Project, health advocates worked with farming interests to advocate for legislation that benefited both sides. Virginia ultimately allocated 10% of MSA funds to the Tobacco Settlement Foundation to reduce youth tobacco use and 50% to the Tobacco Indemnification Commission, for economic development, diversification, and reimbursement to the tobacco farmers for their economic loss.83

Deepening Rift Between the Manufacturers and the Farmers. The growing rift between the tobacco manufacturers and the farmers was evident when in February 2000, 7 tobacco farmers brought a class action lawsuit against Philip Morris, Lorillard, Brown & Williamson, RJ Reynolds, and several leaf tobacco dealers, alleging that the cigarette companies had misled them about the payments they would receive in exchange for opposing the McCain bill.9 The farmers alleged that the cigarette companies and leaf dealers conspired to fix prices at tobacco auctions and reduce tobacco-growing quotas.102 All the parties, except RJ Reynolds, settled the case in May 2003, and RJ Reynolds settled in 2004.102 The farmers received approximately $254 million. Philip Morris, Lorillard, and Brown & Williamson agreed to buy 405 million pounds of domestic tobacco over 10 years, and RJ Reynolds agreed to buy at least 35 million pounds.103

Farm interests also stopped opposing some tobacco-control policies in the tobacco-growing states. In North Carolina in 2003, in an early break from the tobacco companies, farm interests did not oppose a bill restricting tobacco use in public schools.9 The shift in alliance between the tobacco growers and the tobacco manufacturers weakened the issue network in tobacco-growing states such as South Carolina, which historically had relied on alliances among bureaucrats, such as the commissioner of agriculture, legislators from the tobacco-growing areas, and third-party allies such as tobacco-farming organizations. After these changes in the structure of the tobacco market, there was a shift in the issue network, with the commissioners of agriculture and the farm bureau in South Carolina switching from opposing to remaining neutral on tobacco-control policies.20

Also in 2003, Rod Kuegel, a Kentucky tobacco farmer, former president of the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative, and member of President Clinton's 2000 Commission on Improving Economic Opportunity in Communities Dependent on Tobacco Production While Protecting Public Health, partnered with Kentucky ACTION (a tobacco-control coalition) to secure a resolution from the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative to support raising the tobacco tax.104 Kuegel explained his support in the Owensboro Messenger Inquirer:

Two years ago it would have been impossible to have an endorsement from farmers that the excise tax needed to be considered. But last month, the co-op made a resolution to do just that. Increasing the excise tax won't hurt Kentucky farmers. More than half of the tobacco in a cigarette—55 percent—is grown overseas. Even if every smoker in Kentucky quit, the demand for the state's burley would drop by only 2 percent.104

Even though the cigarette companies successfully blocked the tax through lobbying and campaign contributions, this battle marked a change in the alliance between the tobacco farmers and the tobacco companies.8

Similarly, in 2005 the president of the Farm Bureau told the Lexington Herald Leader,

A tobacco tax increase is inevitable and the Farm Bureau will reverse its longstanding position. Our organization has opposed these types of proposals from its earliest days. The organization will throw its considerable influence behind an increase in the tax on tobacco products…and some of the proceeds should go to make payments farmers were expecting from tobacco manufacturers.105

This was a change in their position from 2002 when they had stated, “A lot of cigarettes in Kentucky are sold for the fact that we do have lower taxes…it might be the case where you could triple the excise tax and still lose money because sales would drop.”106

After the Tobacco Quota Buyout. By 2004, there was substantial support for the buyout, including that of Republicans. For example, in May 2004, the Washington Post reported, “Tobacco States Fume Over Bush Remarks: President Says He Opposes a Buyout for Growers, Angering Some From His Party.”107 The article continued, “Tobacco state lawmakers from his own party responded with confusion and anger to Bush's comments [regarding not supporting the buyout],” quoted Representative Virgil H. Goode (R-VA) as saying, “I've heard from any number of good Republicans who say they'll either stay home or vote Democrat in the fall if the White House doesn't change its position,” and concluded,

Support for a buyout is almost universal among tobacco growers. Changes in the market and increasing competition from foreign-grown tobacco have already put thousands of U.S. tobacco farmers out of business, and they have looked to a buyout of the government-controlled quota system as the only way to stay solvent.107

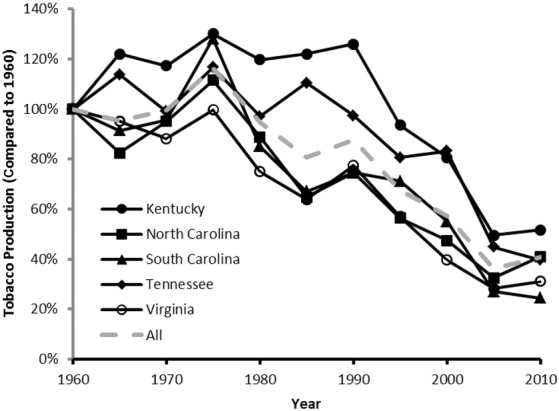

In 2004, President George W. Bush (R) signed the Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act, ending the federal price support program for tobacco and deregulating both the production and the price of tobacco.108 It also required the tobacco manufacturers to pay more than $3 billion to existing quota holders.108,109 The quota buyout led smaller farmers to stop growing tobacco,110 leaving fewer tobacco farmers with an interest in opposing tobacco-control policies. These changes were reflected in the amount of tobacco grown per year, which has declined dramatically since the 1960s in all 5 of the major tobacco-growing states (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tobacco Production Has Declined Since 1960 in All 5 Major Tobacco-Growing States

This decline was described by a farmer in North Carolina to a local newspaper:

As far as backbone, it's [tobacco's] not. The number of people that's involved in it [tobacco farming] keeps thinning down. At one time, this area, about all of the boys, a lot of them would have an acre or two if they didn't have any. Now the only ones raising it are the guys who are leasing the land and raising the big pounds.111

Similarly, in 2011, the director of the Guilford County, North Carolina, Cooperative Extension Service told the High Point Enterprise, “We kind of have a core group of tobacco farmers…back at the time of the tobacco buyout, there was probably 200 tobacco growers. Everybody had a batch of tobacco because it was profitable and it was paying the bills.”111 Continuing this trend, in 2010 a burley tobacco specialist at the University of Tennessee Extension in Knoxville, told the Knoxville News Sentinel,

East Tennessee [tobacco growing] is down very much in the last 10 years. That's due to the change in government policy and the elimination of the price support program that resulted in lower prices and a lot of people getting out of the business.…Since the buyout, in Tennessee probably 80 to 90 percent of the folks that were growing have quit.112

A Tennessee tobacco farmer also explained to Knoxville News Sentinel in 2010 that he had been “better off during the auction system. Now, they pay you just enough money to keep you interested.”112

These changes also led to a measurable shift in farmers’ attitudes toward both the tobacco companies and public health groups. North Carolina farmers were less likely to believe in 2005 than in 1997 that tobacco farmers do well when the tobacco companies do well (OR 3.16, 95% CI 2.24-4.46).113 They were less likely to believe public health groups were interested in driving them out of business (OR 0.68, CI 0.49-0.95), and they also perceived a lower risk from potential FDA regulation in 2005 (OR 0.14, CI 0.10-0.20).113

Tobacco-Control Progress in Tobacco-Growing States: 2000 Onward

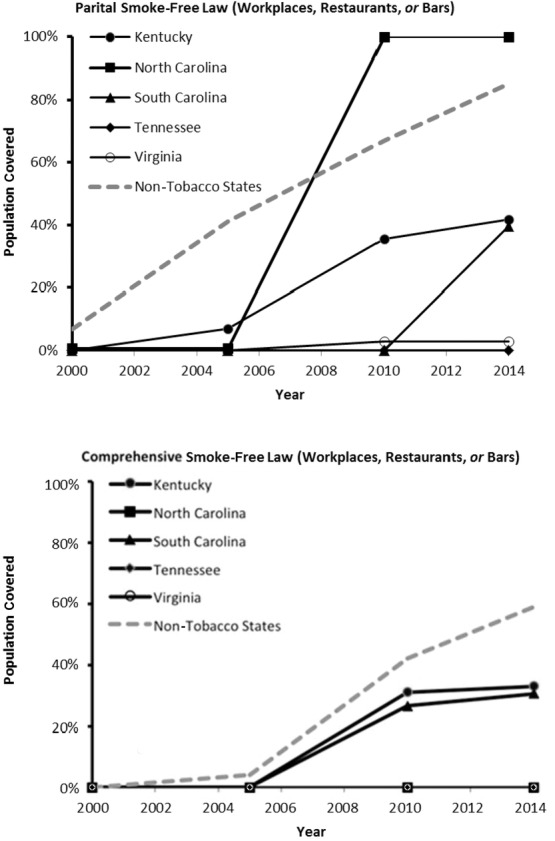

In the mid- to late 2000s, tobacco-growing states made progress in their adoption of clean indoor air laws (Figure 2). In 2003, Lexington, Kentucky, adopted the first comprehensive (public places, restaurants, and bars) 100% smoke-free law in a tobacco-growing state, and by June 2014 the states had passed 38 laws and local regulations.114 On June 19, 2014, the number dropped to 35 laws when the Kentucky Supreme Court overturned the right of the boards of health to enact smoke-free regulations.115

Figure 2.

Coverage by 100% Smoke-Free Laws Is Increasing in Tobacco-Growing States in Many Venues (top), Including Comprehensive Laws (bottom) (American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation Local Ordinance Database, August 2014)

By the mid- to late 2000s, North Carolina's tobacco-control advocates had succeeded in using a “chipping away” strategy to promote smoke- and tobacco-free policies in areas that were not preempted, such as hospitals and schools. In 2006, the changing social and political environment allowed health advocates to win a law prohibiting tobacco use inside prisons and, in 2008, on prison grounds. In 2006, the Healthy North Carolina Hospital Initiative, a partnership between the North Carolina Hospital Association and the North Carolina Prevention Partners, received funding from the Duke Endowment to work for voluntary 100% tobacco-free hospital regulations. In 2007, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a law requiring 100% tobacco-free schools,9 and in 2009, North Carolina became the first state in the nation to achieve voluntary 100% tobacco-free policies in all its acute, psychiatric, and Veterans Affairs hospitals.

In 2009, the North Carolina Restaurant and Lodging Association switched sides to ally with the tobacco-control advocates (because the health advocates were supporting smoke-free restaurants and bars, creating a “level playing field”), which allowed health advocates to convince the legislature to enact a strong smoke-free restaurant and bar law. Although the tobacco companies maintained a lobbying presence during this time, they did not have active support from the tobacco farmers. North Carolina became the first major tobacco-growing state to adopt a 100% smoke-free law covering bars and restaurants.9

Another major change in the political environment in Tennessee in tobacco control came in 2006 when, while signing a smoke-free state government buildings law, Governor Phil Bredesen (D) announced his support for a comprehensive state smoke-free law.116 The Campaign for a Healthy and Responsible Tennessee (CHART), a tobacco-control coalition, used this announcement to generate grassroots support for a state smoke-free law.

By 2007, when Governor Bredesen pursued multiple tobacco policies, including comprehensive smoke-free legislation and a 42¢ tobacco tax, the climate surrounding tobacco had dramatically changed in Tennessee. As Governor Bredesen told the New York Times, “It's something [a smoke-free law] you couldn't have done in Tennessee a decade ago. I think people are ready for it. Everything is not seen through the prism of being a tobacco state.”117 CHART, along with the Tennessee Restaurant Association and the state's Department of Health, supported a comprehensive workplace smoke-free law that also included restaurants and bars.12 Tennessee's Farm Bureau was not actively involved and did not take a formal position in the debate over Tennessee's statewide smoke-free law.116 Health groups broke with the Restaurant Association and accepted a weakened bill that exempted age-restricted venues, hotels and motels, and tobacco retail stores and continued preemption of the passage of local smoke-free laws.

The Split Between the Cigarette Companies and the Hospitality Associations. One of the factors that contributed to progress in the tobacco-growing states was the split between the cigarette companies and the hospitality organizations, as demonstrated by the cases of North Carolina and Tennessee. The tobacco industry's alliance with the state restaurant associations fractured after it became evident that, contrary to the tobacco industry's claims, smoke-free policies did not harm the restaurant business. In addition, restaurant associations shifted from opposing policies to supporting comprehensive policies because they were interested in having a level playing field in which both restaurants and bars were included in a smoke-free law (versus restaurants alone) so that the bars would not receive an “unfair advantage.”118 Restaurant associations may have also gotten tired of opposing smoke-free laws. A Philip Morris presentation in 2001 titled “Smoking Restrictions in the United States, Confidential Draft—for Discussion Purposes Only,” describing current trends in smoke-free policies across the country, stated: “Restaurant associations are now even proposing legislation to ban smoking in restaurants themselves (OR & WA). They are tired of the fight and have more pressing business issues to deal with.”119 Although the split between the tobacco industry and the hospitality organizations occurred throughout the country, it may have been more influential in the tobacco-growing states because they lagged behind the non-tobacco-growing states in their adoption of smoke-free laws.

The Continued Impact of the Pro-Tobacco Social Norm. Despite these successes, as well as the reduction in tobacco production (Figure 1), the culture of being a tobacco-growing state still holds back tobacco-control progress in these states. For example, in 2011 a North Carolina fifth-generation tobacco farmer who stopped growing tobacco in 2003 told the High Point Enterprise, a North Carolina newspaper, “People don't realize what tobacco did for this state. Winston-Salem was built on tobacco. Like Baptist Hospital, there's no telling how much money that Reynolds gave them over the years. It's just amazing. There's no telling how many people these plants, tobacco, has sent to college over the years.”120

In 2014, the Lexington Herald Leader reported that the tobacco heritage in Bourbon County, Kentucky, was holding back tobacco-control progress. Also in 2014, the Lexington Herald Leader published a story about local activists working for a smoke-free law that focused on tobacco heritage, describing a mural of the tobacco harvest that had been on the Bourbon County Courthouse rotunda for more than a century. In the article, the county executive cited this history as the reason Bourbon County would not enact a smoke-free law, because “Burley put me through school. Burley built this courthouse, burley built the schools, burley put food on the table…just about every county farm raised some amount of tobacco.”121

Farm organizations have not completely stopped opposing tobacco-control policies either: in 2014, the Kentucky Farm Bureau lobbied against a statewide clean indoor air law. Also in that same year, the Kentucky Supreme Court overturned the board of health's smoke-free community regulations, citing the controversial nature of the plant as well as the state's tobacco-growing history and culture:

Spanning Pikeville to Paducah, rare is the hill, hollow or hamlet that remains untouched by the legacy of this controversial plant. For example, images of tobacco leaves are molded into the façade of the Caldwell County Courthouse in Princeton, Kentucky as an enduring testament to our agrarian history and culture. Further illustration may be gleaned from the large quilt that hangs on the first floor of our state Capitol building. It has been woven together with 120 sections representing the individual identities of each of our Kentucky counties. More than a dozen of these quilted sections have tobacco plants artistically stitched upon them. These examples are representative of the undeniable impact of tobacco on Kentucky's economic, social and political history.115

The impact of the continued pro-tobacco social norm hinders progress on controlling tobacco and may partially explain the continued disparity in percentages of the population covered by smoke-free laws (Figure 2) and the differences in tobacco taxes. As of 2014, the average tobacco tax rate in tobacco-growing states was 48.5¢ per pack compared with $1.68 per pack in other states.122

Discussion

Since the time of the Night Riders in the early 1900s, the relationship between farmers and manufacturers in tobacco-growing states has been in flux. By the 1950s, when the health dangers of smoking were becoming widely recognized by the public, tobacco farmers and manufacturers partnered to influence public perception of smoking and tobacco-control policy.36 They formed a policy issue network7 of tobacco-area legislators, farm interest groups, and commissioners of agriculture to block tobacco-control policies.20 By the 1970s, tobacco trade associations were particularly concerned about holding back the tobacco-growing states from adopting tobacco taxes. In these states, the tobacco companies promoted a pro-tobacco social norm and Pride in Tobacco to mobilize growers to oppose tobacco-control policies.

The clean indoor air movement began in the 1970s, and by the 1990s, Virginia and North Carolina were enacting local-level smoke-free policies.9,11 To oppose clean indoor air policies nationwide, the tobacco industry worked with hospitality groups to encourage accommodation,69 organize smokers’ rights groups,65 and promote preemption.68 Preemption was particularly successful in the tobacco-growing states, with 3 of the 5 (60%; North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) adopting some form of preemption by 2007. In comparison, 10 of the remaining 45 (22%) non-tobacco-growing states had a preemptive law. Although North Carolina has strong statewide smoke-free legislation covering restaurants and bars but not workplaces, the 3 states continue to have some form of preemption, and none has enacted comprehensive smoke-free legislation (workplaces, restaurants, and bars).

In the 1990s and 2000s, major changes separated the interests of growers and manufacturers, including the companies’ increased purchase of foreign tobacco, the MSA, and the tobacco-quota buyout. These changes ultimately led to fewer farmers and a fracturing of the grower-manufacturer alliance, making it easier for tobacco-control interests to succeed. At the same time, the strong alliance between hospitality organizations and the manufacturers ended, which was also helpful to tobacco-control advocates.

This article supports the work of Klein123 and Greathouse124 indicating that strong coalitions are needed to achieve smoke-free policies in the tobacco-growing states. North Carolina has built a lasting infrastructure and has had significant success in adopting clean indoor air laws.9 In Virginia, ASSIST helped develop a coalition, and one of the coalition partners, the University of Virginia Institute for Quality Health, was awarded a SmokeLess States grant. This grant brought together farmers and tobacco-control advocates and eventually led to the Southern Tobacco Communities Project.11

One factor that may have contributed to the passage of the states’ weak, preemptive smoking restriction laws is the lack of recognition by the public, policymakers, and even health advocates of the changed reality of tobacco's importance to the local economy. (The failure to appreciate this change also may have contributed to the coalition conflict that led to the passage of the weak preemptive law in Tennessee.) Despite the reality that tobacco production has fallen dramatically since 1997 (the year before the MSA), the tobacco-growing states continue to be hindered by long-lasting assumptions about the cultural value of tobacco.121,123

Despite these barriers, the tobacco-growing states have made progress in tobacco control, particularly in adopting smoke-free policies. To continue this progress in the adoption of clean indoor air laws, as well as tobacco taxes, health advocates in the tobacco-growing states should educate the general public and policymakers about the changing realities of tobacco. Given the continued importance of tobacco as a cultural construct, residents and policymakers in tobacco-growing states may not be aware that (1) the domestic demand for cigarettes has declined;91 (2) tobacco manufacturers are increasingly importing foreign tobacco;20,87 (3) there is increasing distance between the tobacco manufacturers and the tobacco farmers; and (4) there are fewer tobacco farmers since the tobacco-quota buyout.110,120

Limitations

Our analysis relied on existing case studies, media articles, and the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library. As with all case studies, it is possible that some relevant information was missed. In addition, the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library is not a complete archive and relevant documents may be missing.

Conclusions

The tobacco-growing states have lagged behind the rest of the country in tobacco-control policies, and residents of these states are disproportionately affected by tobacco-related disease. Nevertheless, there has been rapid progress since 2003, at least in part because the cigarette companies can no longer rely on local farmers for political support to oppose local and state tobacco-control policies. Since the 1990s, the fracturing of the relationship between the tobacco manufacturers and growers, as well as the distancing between the tobacco manufacturers and hospitality organizations, has led to tobacco-control success. To continue to make progress, health advocates should recognize the changing environment and avoid compromises that reflect old realities, such as the compromise in Tennessee that led to a weak, preemptive statewide law. In addition, health advocates should educate the public and policymakers (and themselves) about the changing reality in these states, notably the major reduction in the number of tobacco farmers, as well as in the volume of tobacco produced, in order to continue making progress on tobacco control and reducing the burden of tobacco-induced disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Washington for research assistance.

Funding/Support

This project was supported by National Cancer Institute grants CA-060121 and CA-113710 and California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program grant 22FT-0069. The funding agencies played no role in the selection of the research question, the conduct of the research, or the preparation of the article.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Both authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No disclosures were reported.

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lung and bronchus cancer incidence rates by state, 2009. 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/statistics/state.htm. Accessed May 3, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division for heart disease and stroke prevention: data trends and maps [no date]. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/NCVDSS_DTM/#. Accessed May 3, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and tobacco use. 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/state_data/state_highlights/2012/map/index.htm. Accessed January 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Nimsch CT. Impact of cigarette excise tax increase in low‐tax southern states on cigarette sales, cigarette excise tax revenue, tax evasion, and economic activity: final report. Prepared for Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium; 2003.

- Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights. U.S. 100% smokefree laws in non‐hospitality workplaces and restaurants and bars. 2013. http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/WRBLawsMap.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Young TV, Lewis WD, Sanders MS. Structural location and reputed influence in state reading policy issue networks. Am J Educ. 2010;117(1):25‐49. [Google Scholar]

- Washington MD, Barnes RL, Glantz SA. Good start out of the gate: tobacco industry political influence and tobacco policymaking in Kentucky 1936‐2012. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/10k3p8m5. San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Washington M, Barnes RL, Glantz SA. Chipping away at tobacco traditions in tobacco country: tobacco industry political influence and tobacco policy making in North Carolina 1969‐2011. San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Barnes RL, Glantz SA. Shifting attitudes toward tobacco control in tobacco country: tobacco industy political influence and tobacco policy making in South Carolina. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/278790h5%20. San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kierstein A, Barnes RL, Glantz SA. The high cost of compromise: tobacco industry political influence and tobacco control policy in Virginia, 1977‐2009. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gm9794g. San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mamudu H, Dadkar S, Veeranki S, He Y, Barnes R, Glantz S. Multiple streams approach to tobacco control policymaking in a tobacco‐growing state. J Community Health. 2013:1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SJ, McCandless PM, Klausner K, Taketa R, Yerger VB. Tobacco documents research methodology. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(Suppl. 2):ii8‐ii11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Institute. Tennessee & tobacco [no date]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qzm82b00/pdf.

- Snow Jones A, Austin WD, Beach RH, Altman DG. Tobacco farmers and tobacco manufacturers: implications for tobacco control in tobacco‐growing developing countries. J Pub Health Policy. 2008;29:406‐423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milov S. Little tobacco: the business and bureaucracy of tobacco farming in North Carolina [dissertation]. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt AM. The Cigarette Century. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nall JO. The tobacco night riders of Kentucky and Tennessee. 1939. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wyk19a00.

- Womach J. Tobacco price support: an overview of the program. 1998. http://www.cnie.org/nle/CRSreports/agriculture/ag-61.cfm. Accessed January 7, 2014.

- Sullivan S, Glantz S. The changing role of agriculture in tobacco control policymaking: a South Carolina case study. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1527‐1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull DD. Tobacco is going, going…but where? Cult Agriculture. 2009;31(2):54‐72. [Google Scholar]

- Hull JW. Tobacco in transition: a special series report of the Southern Legislative Conference. Atlanta, GA: Southern Legislative Conference; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Associates Inc. First—what is Tobacco Associates? 1976. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dmr59b00.

- Warner KE. Regional differences in state legislation on cigarette smoking. Texas Business Review. January/February 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Tax Council. Tobacco organizations. 1978. RJ Reynolds. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mra29d00.

- Tobacco Associates Inc. Twenty‐fifth annual report. February 29, 1972. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hor59b00.

- Tobacco Tax Council. Budget—1976. 1976/E. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/afw98b00.

- Giraldi AW, Bowling JC. Tobacco Tax Council budget. December 12, 1974. Philip Morris. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xxl78e00.

- Tobacco Tax Council. Tobacco Tax Council budget—1972. 1972. American Tobacco. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mug12i00.

- Tobacco Tax Council. Tobacco Tax Council budget for 1953‐54 and 1954‐55. 1954. {est.}. Lorillard. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jwr88c00.

- Tobacco Tax Council. Budget—1979. 1979. RJ Reynolds. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mjz39d00.

- Mozingo R, Cannell B. Analysis of TTC board of directors. 1981. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ipn03b00.

- Norr R. Cancer by the carton. Reader's Digest. December 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor RN. Golden Holocaust: Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Darrow RW. Notes on minutes of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee meeting—12/28/1953. Philip Morris. 1953. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jye62c00.

- Tobacco Industry Research Committee. A frank statement to cigarette smokers. Lorillard. 1954. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hsg46b00/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Morley CP, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Giovino GA, Horan JK. Tobacco Institute lobbying at the state and local levels of government in the 1990s. Tobacco Control. 2002;11(Suppl. 1):i102‐i109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States of America et al. v Philip Morris USA US District Court for the District of Columbia. http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/doj-final-opinion.pdf.

- Chilcote S. A draft planning prospectus for a new national tobacco organization. 1982. {est.}. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zor55b00.

- Tobacco Growers Information Committee. Statement of operations and budgets for the years ended 8/31/92 & 8/31/93. August 31, 1992. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gwh88b00.

- Tobacco Growers Information Committee. Statement of income and expense. June 30, 1985. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rps87b00.

- Lester R. Financial statement. June 10, 1983. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jvs87b00. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Growers Information Committee. 1986‐1987 proposed contributions. 1986/E. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/adt87b00.

- Tobacco Growers Information Committee. Executive committee meeting, May 30, 1985, agenda. May 30, 1985. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tqs87b00.

- Ragland EF. Talk before Burley Leaf Tobacco Dealers Association. 1958. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/udi29d00/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Otanez MG, Glantz SA. Trafficking in tobacco farm culture: tobacco companies’ use of video imagery to undermine health policy. Vis Anthropol Rev. 2009;25(1):1‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Tax Council Inc. [no title.]. 1973. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/abe30g00.

- O'Flaherty W. State taxes big threat to U.S cigarette sales. April 26, 1974. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qwz48b00. [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty W. Outlook for taxes in the cigaret [sic] industry. June 9, 1975. Brown & Williamson. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yth53f00. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland P. Dear Mr. Miles. November 26, 1980. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sfg30g00. [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty WA. Address to Tobacco Growers’ Information Committee, November 2, 1970. Tobacco Institute. February 28, 1970. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eua29b00. [Google Scholar]

- Maddock HJ, Tobacco Tax Council. The war is not over. 1977. {est.}. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eqp07d00. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Associates Inc. Thirty‐second annual report. 1979. Tobacco Institute. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lmx08b00. [Google Scholar]

- Cardador MT, Hazan AR, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry smokers’ rights publications: a content analysis. Am J Pub Health. 1995;85(9):1212‐1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]